“WHEN EVERYBODY GETS TO ONE SIDE OF THE BOAT, IT USUALLY TIPS OVER.” THAT SAYING MAY have originated on Wall Street, but it also stands as a warning to those charting the future of U.S. biomedical research. If the United States focuses too much of its investment on one part of the research continuum, the entire enterprise may sink.

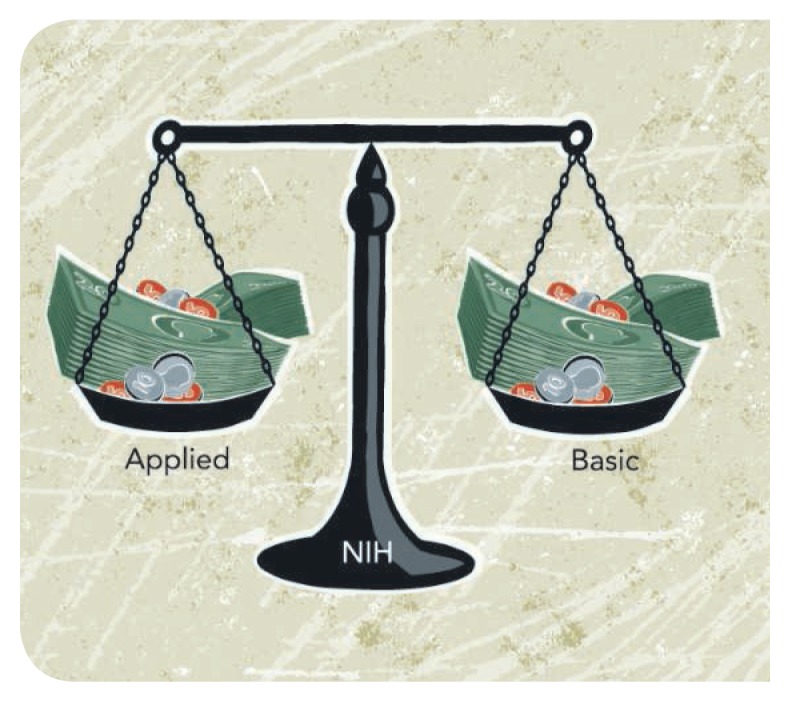

Perhaps with this in mind, some have questioned whether, in its quest to draw attention to translational research, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) may be underemphasizing basic research. The NIH will most assuredly continue its strong tradition of supporting basic research, which it defines as systematic study directed toward fuller knowledge or understanding of the fundamental aspects of phenomena and of observable facts without specific applications in mind. Since 2003, the proportion of NIH funds spent on basic research, defined in this way, has ranged from 53 to 57%, standing at 54% for fiscal year (FY) 2012.

A scan of Science’s top breakthroughs of 2011 shows that NIH-funded research and/or research resources enabled four of the six advances related to life sciences: three basic (cell senescence, human microbiome, archaic human DNA) and one clinical with deep roots in basic research (HIV treatment as prevention). Basic research also accounts for most of the 135 Nobel Prizes won by NIH-supported scientists, including the 2011 awards to Bruce Beutler and Jules Hoffmann for their discoveries about innate immunity, and the late Ralph Steinman for adaptive immunity. Likewise, current NIH grantee Arthur Horwich and past grantee F. Ulrich Hartl captured 2011 Lasker awards for landmark explorations of the cell’s protein-folding machinery. Their work, which provided insights on protein misfolding in neurodegenerative disease, is among countless examples of basic research, including that with model organisms,* giving rise to medical advances.

But what is NIH doing to fuel the next generation of breakthroughs? The agency is supporting basic research in all of Science’s biomedical “Areas to Watch” in 2012: elucidating metabolic pathways in stem cells; whole-genome sequencing for epidemiology; and developing new models of developmental brain disorders. NIH’s institutes and centers also survey the basic research horizon for exciting opportunities in their realms. Examples include efforts to understand the roles of microRNAs and competing endogenous RNA in gene regulation; detailed analyses of Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans biology supported by modENCODE (the identification of all functional elements of selected model organism genomes); and a trans-NIH effort to map the brain’s wiring in high resolution. The NIH Common Fund† has built a portfolio designed to tackle some of biology’s most fundamental questions, including new efforts in extracellular RNA communication and single-cell analysis. The Common Fund’s High-Risk/High-Reward program has grown from $7.3 million in 2004 to $191.8 million in 2011, and further increasing the number of Pioneer and New Innovator awards will be a top NIH priority in FY2014. These awards are open to exceptionally creative scientists in any area of biomedical research, and if past trends continue, basic research will dominate.

In this time of severe budget constraints,‡ Americans need to know that today’s basic research is the engine that powers tomorrow’s therapeutic discoveries. They need to know that basic research is the type of science that the private sector, which requires rapid returns on investment, cannot afford to fund. They need to know that, because it is impossible to predict whence the next treatment may emerge, the nation must support a broad portfolio of basic research. And they need to hear it from all aboard the biomedical research ship, whether they are port, starboard, or somewhere in between.

Footnotes

A. D. Gitler, R. Lehmann, Science 337, 269 (2012).

H. R. Bourne, M. O. Lively, Science 337, 390 (2012).