Abstract

A sonication accelerated, catalyst free, simple, high yielding and efficient method for the Passerini-type three component reaction (PT-3CR) has been developed. It comprises reaction of an aldehyde/ketone, a isocyanide and a TMS-azide in methanol:water (1:1) as the solvent system. Use of sonication not only accelerated the rate of the reaction but also provided up to quantitative yields. This reaction is applicable to a broad scope of aldehyde/ketone and isocyanides.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

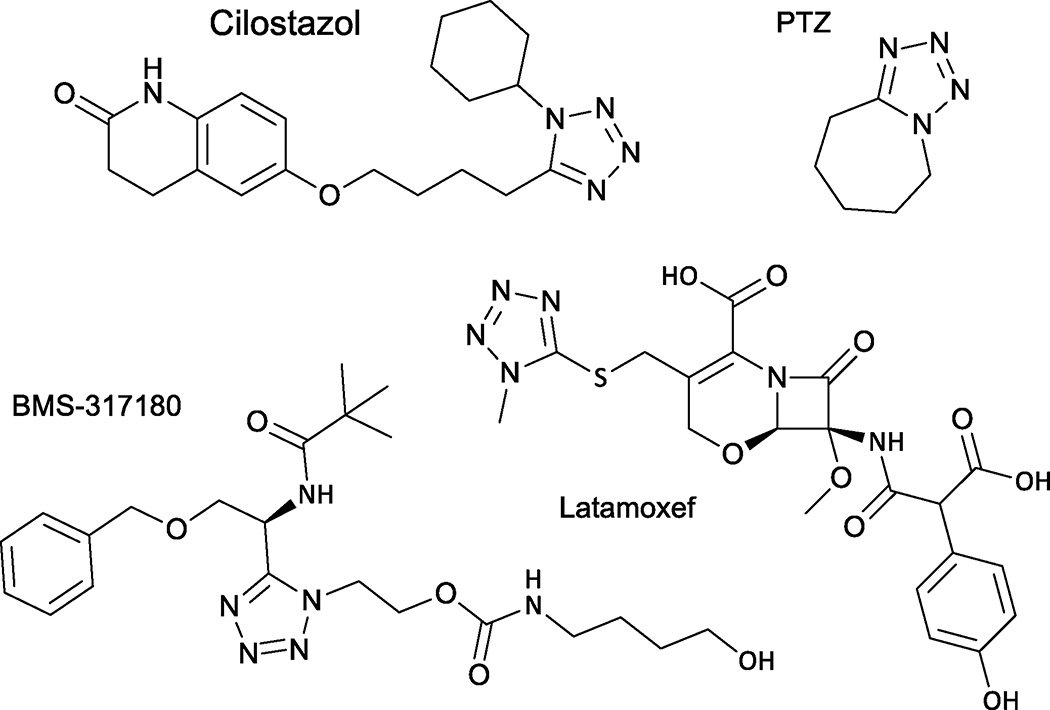

Tetrazoles scaffolds are extensively used in medicinal chemistry and in industry like agriculture, explosives and photography.1 1,5-disubstituted tetrazoles are important ring system having applications as, bio-active agents or drugs like cilostazol, pentylenetetrazole, latamoxef, BMS-317180 and cis-amide bond isosteres in peptides (fig 1). This propel the need for efficient synthetic methods for tetrazoles.2 Different reactions have been developed for the direct access to diverse 1,5-disubstituted tetrazoles, but three and four-component reactions (MCR) are mostly preferred due to its convergent, atom-efficient and flexible nature.3 Multicomponent reactions are considered an ideal synthesis and that’s why its use in synthetic chemistry is tremendously increasing.4

Fig 1.

Some bio-active agents/drugs containing the tetrazole moiety.

In 1921, three component reaction between carboxylic acids, oxo components and isocyanides for the synthesis of α-acyloxy amide was discovered by Passerini (P-3CR).5,7c In 1961, Ugi reported the first time the synthesis of tetrazoles via Passerini-type 3CR (PT-3CR) using HN3 and Al(N3)3.6 Even though the use of HN3 or NaN3 in Passerini reaction for the synthesis of tetrazoles PT-3CR was reported, the highly toxic and explosive nature of HN3 and NaN3 limit its application.7 Use of TMSN3 as a safe substitute for HN3 was then introduced by Hulme.8 However TMSN3 use as azide source in the PT-3CR resulted into very low yield and the TMS-ether was found as a major product instead. Similarly protected amino aldehydes in DCM also resulted in generally low yield9 and the described reaction times were up to 96 hours.9a Reported PT-3CR are not well suitable for the aromatic aldehydes.7 The use of different Lewis acids as catalyst like AlCl3 to activate aldehydes forms inseparable mixture of desired product with α-hydroxy-amide with a maximum of 30% yield.10 Zhu and co-workers used TMSN3 as test reaction component in the asymmetric PT-3CR, nevertheless they could not avoid the formation of α-hydroxy-amide.7b

To the best of our knowledge, no efficient, diverse and high yielding PT-3CR reaction has yet been reported. We report herein a sonication-promoted catalyst free, TMSN3-modified PT-3CR using methanol:water (1:1) as solvent with diverse scope and affording good to excellent yields.

Results and discussion

We started our investigation by using tert-butyl isocyanide, phenylacetaldehyde and TMSN3 as starting materials (Table 1). We hypothesized that, the use of fluoride ion sources like TBAF, CsF and KF could trigger both TMSN3 activation.11 However when the reaction was carried out with TBAF with different solvents like DCM, water or neat, the product was formed only in trace amount (Table 1, entries 1–3). Surprisingly methanol as a solvent increased the isolated yield to 25%. Carrying out the reaction with alternative F- sources, KF in DCM or CsF in DCM, methanol and water resulted only in small amounts of product formation.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditionsa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Solvent | Time (h) | Product Yield%b |

| 1 | TBAFc | - | 12 | trace |

| 2 | TBAFd | DCM | 12 | trace |

| 3 | TBAFc | H2O | 12 | trace |

| 4 | TBAFc | MeOH | 12 | 25 |

| 5 | KFe | DCM | 12 | nd |

| 6 | CsFf | DCM | 12 | nd |

| 7 | CsFf | MeOH | 12 | nd |

| 8 | CsFf | H2O | 12 | nd |

| 9 | I2f | DCM | 12 | nd |

| 10 | I2f | H2O | 12 | nd |

| 11 | H2O | 12 | 17 | |

| 12 | TBAFc | MeOH:H2O (1:1) |

12 | 63 |

| 13 | MeOH:H2O (1:1) |

12 | 64 | |

| 14 | Sonication | MeOH:H2O (1:1) |

2 | 97 |

| 15 | Sonicationg | - | 3 | 31 |

| 16 | Sonication | DCM | 2 | 34 |

| 17 | Sonication | H2O | 2 | 71 |

The reaction was carried out with phenylacetaldehyde (1 mmol), tert-butyl isocyanide (1 mmol), and TMSN3 (1 mmol) at room temperature.

Yield of isolated product.

1 equivalent TBAF. 3H2O.

1 equivalent TBAF in 1M THF.

1 equivalent KF.

1 equivalent CsF.

reaction carried out at 70 °C.

nd-not determined

Use of Iodine, to trap TMS as TMSI also fails to improve the reaction yield. 17% product formed when reaction was carried out in water without any additive. TBAF in methanol:water (1:1) enhanced the yield up to 63%; however comparable yield were received when the reaction was carried out without TBAF in the same solvent system. Thus we concluded that the use of TBAF is not fruitful, where as the solvent system has a major impact.

We foresaw that the accelerating effect of sonication could potentially speed up the reaction and increases yields. Ultrasound in general12 and also in the context of MCR12d is often used in organic synthesis due to its advantages such as, increase reaction efficacy while decreasing waste byproducts, short reaction times, cleaner reactions, easier experimental procedure and having low energy requirements. Recently popularity of sonication-assisted synthesis as a green synthetic approach is extremely increasing and resulted in a plethora of ‘better’ reactions.13 Ultrasound in chemical reactions works via a physical phenomenon called, “acoustic cavitation”; which forms, expands and collapses gaseous and vaporous cavities in an ultrasound irradiated liquid. A mechanical effect of cavitation destroy the attractive forces of molecules in the liquid phase and so accelerates reaction rates by facilitating mass transfer in the microenvironment.13 To our delight, use of sonication not only accelerated the reaction from 12 to two hours, but provided quantitative yield in methanol:water (1:1) as the solvent system and noteworthy without the necessity of any previously used additive (Table 1, entry 14). We used simple ultrasonic cleaning bath which is most widely available and cheapest source of ultrasonic irradiation. Recent study shows that, both ultrasonic cleaning bath and ultrasonic probe system are efficient in Passerini reaction.14 The ultrasonic cleaning bath offers further advantage like, reaction vessel can be put directly into the bath without any adaptation. In contritely to the ultrasonic probe system, which is more expensive and also require special vessels and so inconvenient to use.

Lastly, reactions under sonication in DCM or at neat conditions provided less yields, 34% and 31% respectively, and the formation of TMS-ether as side product was observed. Pure water as the solvent under sonication conditions provided the product in 71% yield. Use of 1 equivalents of TMSN3 avoids the danger of forming hydrazide from excess azide. This catalyst free reaction doesn’t require any work-up.

With this optimized condition in hand, we next examined the generality of this PT-3CR by reacting different aldehydes with different isocyanides (Table 2). Good to excellent yield were obtained with linear and branched aliphatic aldehydes. Aromatic aldehydes are also compatible substrates for this process (Table 2, entries 15–22). Electron donating (methoxy) and withdrawing groups (Cl, Br, NO2) at different positions like ortho, meta and para are valid providing moderate to good yield. Paraformaldehyde also reacts when pure water was used as the solvent. Reaction with one or six equivalent paraformaldehyde in methanol:water system only forms mono-substituted tetrazole. Benzyl Isocyanide with aliphatic aldehydes gave excellent yield.

Table 2.

Substrate Scope for the PT-3CR a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | 1 | R3b | Yield (%)c |

| Aldehydes | |||

| 1 | C6H5 -CH2-CHO | C6H5-CH2 | 96 (3a) |

| 2 | iPr-CHO | (CH3)3-C | 98 (3b) |

| 3 | CH3-(CH2)2-CHO | C6H5-CH2 | 80 (3c) |

| 4 | C6H5-CH2-CHO | tOctyl | 77 (3d) |

| 5 | iPr-CHO | CN-CH2-CH2 | 72 (3e) |

| 6 | C6H5-(CH2)2-CHO |  |

53 (3f) |

| 7 | C6H5-(CH2)2-CHO | Cy | 76 (3g) |

| 8 | C6H5-CH2-CHO | 2-BrC6H4-CH2 | 77 (3h) |

| 9 | H-CHOd | 2-BrC6H4-CH2 | 42 (3i) |

| 10 | iPr-CHO | 2-BrC6H4-CH2 | 80 (3j) |

| 11 | C6H5-(CH2)2-CHO | (CH3)3-C | 88 (3k) |

| 12 | CH3-CH2-CHO | C6H5-CH2 | 91 (3l) |

| 13 | (CH3)2-CH-CH2-CHO | C6H5-CH2 | 92 (3m) |

| 14 | C6H5-CH2-CHO | (CH3)3-C | 97 (3n) |

| 15 | C6H5-CHO | (CH3)3-C | 41 (3o) |

| 16 | 2,6-(Cl)2C6H3-CHO | C6H5-CH2 | 71 (3p) |

| 20 | 2,3-(Cl)2C6H3-CHO | Cy | 73 (3q) |

| 17 | 2-MeO-5-BrC6H3-CHO | C6H5-CH2-CH2 | 46 (3r) |

| 18 | 2-BrC6H4-CHO | Cy | 60 (3s) |

| 19 | 2-Cl-3,4-(OCH3)2C6H2-CHO | Cy | 42 (3t) |

| 21 |  |

Cy | 39 (3u) |

| 22 | 2,5-(OCH3)2C6H3-CHO | Cy | 48 (3v) |

| Ketones | |||

| 23 | cyclohexanone | C6H5-CH2 | 84 (3w) |

| 24 | 1-benzylpiperidin-4-one | C6H5-CH2 | 46 (3x) |

The reaction was carried out with 1 mmol 1, 1 mmol 2, 1 mmol TMSN3.

cy = cyclohexyl, toctyl = 2-isocyano-2,4,4-trimethylpentane.

Yield of isolated product.

6 equivalent of paraformaldehyde in water as solvent and at 60°C.

iPr = isopropyl

Isocyanides easy to deprotect in acidic and basic conditions are compatible in the developed methodology (Table 2, entries 2, 4, 5). The functional group tolerance of the isocyanide (Table 2, entries 5–6 and 8–10), in this protocol provides multiple opportunities for various further chemical manipulations. For example compatibility of 1,1-diethoxy-2-isocyanoethane as isocyanide component could be used in further reactions as aldehyde or halogens for coupling reactions.

We also explore the scope of ketones in the developed method (Table 2, entries 23 and 24). Cyclohexanone gives good yield 84%. The important building block piperidone is also compatible with the reaction.

Fused tetrazoles are important scaffold as it poses a wide spectrum activity and vast industrial applications. As functional group bearing isocyanides are compatible in our developed method, we foresaw a quick and easy access to fused tetrazole. According to our synthetic plan, the use of functionalized PT-3CR product for post modification would allow an anticipated cyclization process. (1-(2-bromobenzyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)methanol (3i) when refluxed with Copper(II) triflate, in the presence of base it formed 5,11-dihydrobenzo[f]tetrazolo[5,1-c][1,4]oxazepine with 89% yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of fused tetrazole.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed a novel, efficient, safe and general sonication assisted Passerini tetrazole reaction (PT-3CR) to access 5-(1-hydroxyalkyl)tetrazoles in good to excellent yield. The herein described Passerini tetrazole procedure provides multiple advantages over previous described procedures. The reaction does not use highly toxic and explosive staring materials like HN3, Al(N3)3 or NaN3. This catalyst free reaction avoids the use of any dangerous or adverse catalysts such as Al-salen chiral complex, AlCl3. Sonifiactions was found as a superior reaction condition resulting in high conversion and giving high yields of Passerini products and no TMS-ether side product as often observed previously. Sonification is also well known to be compatible with upscaling procedures. The scope of the reaction could be dramatically extended including aliphatic, aromatic aldehydes and also ketones. Due to the extended functional group compatibility of the reaction many new scaffold amenable by post-condensation reactions can be foreseen as we have illustrated by the synthesis of a Cu-mediated fused tetrazole. Altogether we believe that our procedure is superior to all previously reported Passerini tetrazole reactions and will be the method of choice for the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Groningen. The Erasmus Mundus Scholarship “Svaagata” is acknowledged for a fellowship to A. Chandgude. The work was financially supported by the NIH (1R01GM097082-01) and by Innovative Medicines Initiative (grant agreement n° 115489).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.For a review on the importance of tetrazole derivatives, see: Wei CX, Bian M, Gong GH. Molecules. 2015;20:5528–5553. doi: 10.3390/molecules20045528. Roh J, Vavrova K, Hrabalek A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012:6101–6118. Mohite PB, Bhaskar VH. Int. J. Pharm.Tech. Res. 2011;3:1557–1566. Frija LM, Ismael A, Cristiano MLS. Molecules. 2010;15:3757–3774. doi: 10.3390/molecules15053757. Myznikov LV, Hrabalek A, Koldobskii GI. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2007;43:1–9.

- 2.For a review on the synthesis of tetrazole derivatives, see: Malik M, Wani M, Al-Thabaiti S, Shiekh R. J Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2014;78:15–37. Koldobskii GI. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2006;42:469–486. Herr RJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:3379–3393. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00239-0. Zubarev VY, Ostrovskii VA. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2000;36:759–774. Wittenberger SJ. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1994;26:499–531.

- 3.Sarvary A, Maleki A. Mol. Divers. 2015;19:189–212. doi: 10.1007/s11030-014-9553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For a general review on the importance of MCR reactions, see: Dömling A, Wang W, Wang K. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:3083–3135. doi: 10.1021/cr100233r. Zarganes-Tzitzikas T, Chandgude AL, Dömling A. Chem. Rec. 2015;15:981–996. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201500201.

- 5.(a) Passerini M, Simone L. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1921;51:126–129. [Google Scholar]; (b) Passerini M, Ragni G. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1931;61:964–969. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ugi I, Meyr R. Chem. Ber. 1961;94:2229–2233. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Sela T, Vigalok A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354:2407–2411. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yue T, Wang MX, Wang D-X, Zhu J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:9454. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Banfi L, Riva R. Org. React. 2005;65:1–140. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nixey T, Hulme C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:6833–6835. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Monfardini I, Huang J-W, Beck B, Cellitti JF, Pellecchia M, Domling A. J Med. Chem. 2011;54:890–900. doi: 10.1021/jm101341m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schremmer ES, Wanner KT. Heterocycles. 2007;74:661–671. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giustiniano M, Pirali T, Massarotti A, Biletta B, Novellino E, Campiglia P, Sorba G, Tron GC. Synthesis. 2010:4107–4118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amantini D, Beleggia R, Fringuelli F, Pizzo F, Vaccaro L. J Org. Chem. 2004;69:2896–2898. doi: 10.1021/jo0499468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Nasir Baig RB, Varma RS. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:1559–1584. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15204a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cravotto G, Cintas P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35:180–196. doi: 10.1039/b503848k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cintas P, Luche J. Green Chem. 1999;1:115–125. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cui C, Zhu C, Du X-J, Wang Z-P, Li Z-M, Zhao W-G. Green Chem. 2012;14:3157–3163. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Mason TJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997;26:443–451. [Google Scholar]; (b) Abdulla RF. Adrichimica Acta. 1988;21:31–42. [Google Scholar]; (c) Loupy A, Luche JL. In: Synthetic Organic Sonochemistry. Luche JL, editor. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 107–166. [Google Scholar]; (d) Thompson LH, Doraiswamy LK. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999;38:1215–1249. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui C, Zhu C, Du X-J, Wang Z-P, Li Z-M, Zhao W-G. Green Chem. 2012;14:3157–3163. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.