Abstract

Background

In South Korea, the number of workers suffering from mental illnesses, such as depression, has rapidly increased. There is growing concern about depressive symptoms being associated with both working conditions and psychosocial environmental factors.

Objectives

To investigate potential psychosocial environmental moderators in the relationship between working conditions and occupational depressive symptoms among wage workers.

Methods

Data were obtained from the wage worker respondents (n = 4,095) of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 2009. First, chi-square tests confirmed the differences in working conditions and psychosocial characteristics between depressive and non-depressive groups. Second, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the moderating effects of the psychosocial environmental factors between working conditions and depressive symptoms.

Results

After adjusting for potential covariates, the likelihood of depressive symptomatology was high among respondents who had dangerous jobs and flexible work hours compared to those who had standard jobs and fixed daytime work hours (OR = 1.66 and 1.59, respectively). Regarding psychosocial factors, respondents with high job demands, low job control, and low social support were more likely to have depressive symptoms (OR = 1.26, 1.58 and 1.61, respectively).

Conclusions

There is a need to develop non-occupational intervention programs, which provide workers with training about workplace depression and improve social support, and the programs should provide time for employees to have active communication. Additionally, companies should provide employees with support to access mental healthcare thereby decreasing the occurrence of workplace depression.

Keywords: Depressive symptom, Working condition, Psychosocial environments, South Korea

Introduction

One out of five wage workers in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member nations suffer from mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety.1 The number of Korean people suffering from psychological distress and mental health problems by age group was among the highest for OECD countries. The group with the most prevalent mental health problems was people in the working population.2 Although South Korea ranks eighth worldwide in total trade,3 working conditions in South Korea are unsatisfactory. South Korean workers work 44.6 h per week on average, higher than the number of average weekly working hours (32.8) in OECD member nations.4 In addition, during the nation’s process of overcoming national economic default in 1997, many precarious jobs were created and wages decreased to 84.5% of the OECD average.4 Such unstable working conditions have had an adverse effect on South Korean workers’ health status.5,6 In particular, the suicide rate among South Korean workers is 9.47 out of 100,000, the highest rate in the world.7 Nevertheless, little is known about the working conditions and psychosocial factors that affect mental health and depression in South Korean workers.

Studies on the potential associations between psychosocial factors and mental health have been conducted, but mainly in advanced Western nations.8–15 Some of these studies based on work-related stress models16 have pointed out that psychosocial factors such as job demands, low feeling of control over job, and low levels of social support can result in depression in some workers.8–10 Psychosocial factors, such as extreme demands and low decision latitude, are closely related to anxiety and depressive symptoms.10,17,18 Extreme demands combined with low feelings of control (i.e. low decision-making latitude) can cause psychological strain, eventually leading to fatigue, anxiety, and depression.17 Emotional exhaustion and dehumanization can lead to depression.19–21 Finally, low levels of social support reduce an individual’s ability to cope with stressful situations, ultimately aggravating depression and adversely affecting health in the long run.22–24 In contrast, strengthening social support can help prevent depression.9,17,25 Consequently, workers’ psychosocial characteristics are highly likely to be systematically associated with the presence or absence of depression.

However, previous studies have several limitations. First, in terms of research methodology, they had relatively small sample sizes and only took into account specific occupations, making it difficult to generalize their results.9,19,21 To make research results representative, complex sampling designs that consider specific occupations and adjust for occupational types using regression models are needed. Second, previous studies failed to fully consider the effect of working conditions on depression. Depression among workers can be incited by diverse causes in addition to psychosocial factors, with working conditions being seen as the most important non-psychosocial factor.6,11,12,26 Therefore, analyses that combine the effects of working conditions and psychosocial factors are necessary. Third, research studies on depression in workers have been conducted mainly in advanced Western nations. Therefore, it is necessary to examine whether psychosocial factors are determinants of depression among workers in East Asian countries such as South Korea, where daily work hours are long, labor unions are weak, and the culture is patriarchal. The status of workers may be seen as relatively low compared to their Western counterparts. It is necessary to determine whether Western hypotheses are applicable to industrial-based work structures such as those in South Korea.

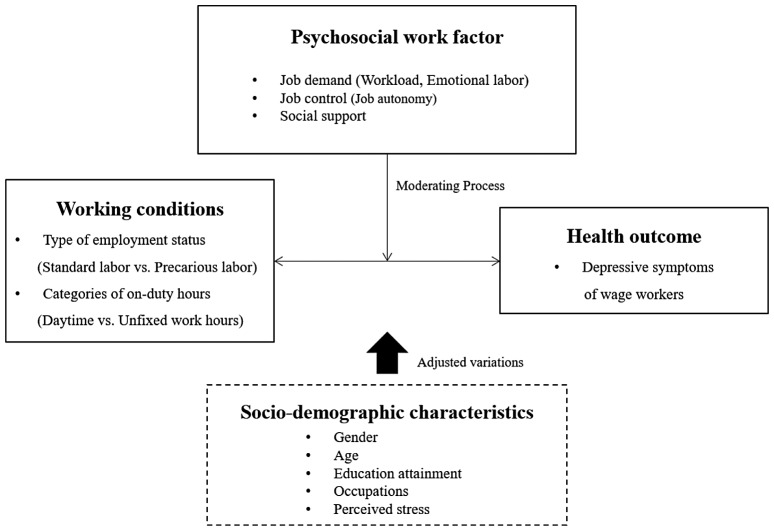

Therefore, this study investigated the psychosocial characteristics of wage workers as moderating factors between working conditions and depressive symptoms (Fig. 1). By exploring the determinants of depressive symptoms, we attempted to draw general conclusions regarding the effects of psychosocial environmental factors on depressive symptoms among wage workers. This study will contribute to the development of a supportive working environment that prevents mental illness in industrial workers.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of this study.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study that examined potential psychosocial environmental moderators in the relationship between working conditions and occupational depressive symptoms among wage workers in South Korea.

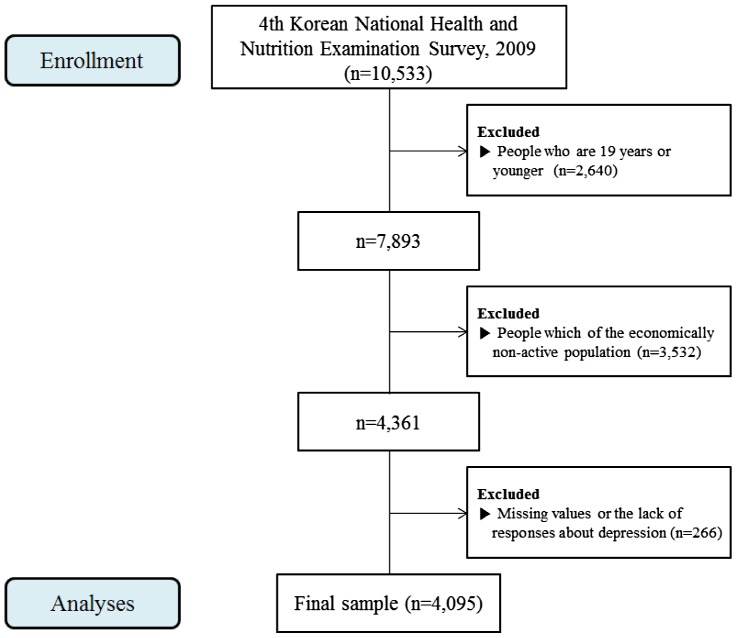

Respondents

Data for this study were taken from the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV-3) conducted by the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention in 2009. The survey was a nationally representative study that used a stratified multistage probability sampling design to select household units. The overall response rate was 82.8% with 10,533 individuals responding. Of those respondents, 2,640 were excluded from the analysis because the respondents were 19 years of age or younger. Another 3,532 adult respondents were excluded because they were members of an economically inactive population. In addition, 266 surveys were excluded because of missing values or a lack of responses about depression. The final sample consisted of 4,095 respondents (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Analytical framework of this study.

Measures

Dependent variable

The main outcome variable was depressive symptoms of wage workers. The following question was asked: “Have you ever felt sadness or a sense of hopelessness that was strong enough to make everyday life unbearable for more than two weeks over the past year?” The responses to this question were dichotomized (yes/no). This is consistent with previous research that used a binary outcome to record occupational depression.27 Although this scale simplifies a complex clinical condition, it can reliably predict the prevalence of depression.28 Additionally, some studies have demonstrated the validity and internal consistency of a single-item measure and its association with the sum of scores of depressive symptoms measured by multiple items.29,30 It has also been validated as a good predictor of suicide.31

Independent variables

Previous studies have reported that dissatisfaction with working conditions, such as job stability and working hours, are associated with negative mental health outcomes among wage workers.5,6,9 In this study, working conditions were grouped by employment status (standard labor vs. intermittent/precarious labor) and on-duty hours (daytime vs. unfixed hours). For employment status, participants were asked to identify their employment stability, with response options of standard labor or precarious labor. Standard employment (employment that did not specify a limited employment period) included full-time jobs offered through a direct contract with the employer.32 Precarious labor (non-standard employment that was poorly paid, insecure, and/or unprotected) included part-time jobs.32 For on-duty hours, participants were asked to identify their on-duty hours, with response options of daytime hours or unfixed hours. Unfixed hours were defined as various shifts including overtime.

Moderating variables

We used three psychosocial environmental factors as moderating variables, in accordance with approaches used in previous studies.13,24,25,33 The effects of job demands, job control, and social support on depressive symptoms were examined in order to identify the effects of psychosocial environmental determinants.

Job demand-control

Karasek’s job demand-control theory was developed as a way to link psychosocial factors present at work to the mental health of workers.34 In the model, job demand includes work speed, quantitative workload, and emotional demands. Control is the ability to make decisions, which can moderate the negative effects of highly demanding jobs on well-being.35 Job demand-control in this study was assessed using the following three questions on workload, emotional labor, and job autonomy. First, workload was assessed with the following question: “Does your job require you to work very fast?” The possible responses were yes and no. Second, emotional labor was assessed by the following question: “Do you worry that this job is taking an emotional toll on you?” The possible responses were yes or no. Third, job autonomy was assessed by the following question: “Are you able to decide for yourself how to carry out your work?” The responses were divided into the following categories: never, seldom, sometimes, or often. Respondents who reported “never” or “seldom” were coded grouped together and respondents who reported “sometimes” or “often” were combined.

Social support

Social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the impact of demands and control on health outcomes.36 Social support in this study was assessed by the following question: “Do you get respect and trust in terms of personal relations at your job?” The responses were divided into the following: strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree. We grouped these answers into two categories. Respondents who reported “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” were grouped together. They were considered the high-support group. Respondents who reported “somewhat disagree” or “strongly disagree” were also combined for analysis. They were considered the low-support group. Use of this simple question has been validated in previous studies on occupational social support.22

Covariates

It has been reported that depression among wage workers can significantly differ by gender, age, educational attainment, occupation, and perceived stress.1,37–43 In this study, we controlled socio-demographic characteristics to identify the net effect of working conditions and psychosocial characteristics on depressive symptoms among wage workers. We also controlled socio-economic status of respondents because these characteristics may influence depressive symptoms. To assess educational attainment, participants were asked to identify the highest level of education that they completed: elementary school or less, middle school, high school to associate, and bachelor’s degree or higher. Occupations were divided into ten groups according to the major categories of the sixth Korean Standard Classification of Occupations: “clerk,” “manager,” “professional and administrator,” “service workers,” “sales workers,” “skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers,” “technicians and associated workers,” “craft, equipment, machine operating, and assembling workers,” “simple labor,” and “soldiers.”

We also controlled for perceived stress as it is a potential moderating factor between working conditions and depressive symptoms. Perceived stress in this study was assessed by responses to the following question: “How often do you feel stressed-out in your life?” The possible responses were: never, seldom, sometimes, and often. Subsequently, we coded the responses into two groups. Respondents who reported “never” or “seldom” grouped together as the low-stress group. Respondents who reported “sometimes” or “often” combined into the high-stress group.

Statistical analysis

The differences in working conditions and psychosocial characteristics between the depressive symptom and non-depressive symptom groups were assessed with Chi-square tests. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze differences in the moderating effects of psychosocial environmental factors between working conditions and depressive symptoms among wage workers after controlling for individual depression-related characteristics. Three representative models were developed in this study: a working condition model (Model I); a job demand, job control, and social support model (Model II); and a model that took into account the interactions between working conditions and psychosocial factors (Model III). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 20.0 (IBM SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

General characteristics of the study subjects

Of the 4,095 participants in this study, 53.5% were men and 46.5% were women. Twenty-four point four percent were in their 30s, and 32.5% had a college degree or higher (Table 1). Regarding occupations, 18.3% were professionals and administrators and 17.4% were clerks. The majority of the participants were standard workers (85.3%), while 14.7% had precarious employment. Most participants worked in the daytime, whereas 16.2% of the participants had no fixed work hours. The majority (68.9%) of participants reported a high level of perceived stress. With regard to psychosocial factors, approximately one-third of the participants reported feeling burdens associated with high workload and emotional burnout. Among those participants, most (75.9%) had low job autonomy. Moreover, 86.4% of the participants responded that they had felt sadness or a sense of hopelessness for more than two weeks in the preceding year.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study subjects

| n | Unweighted % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 2,191 | 53.5 |

| Women | 1,904 | 46.5 |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 | 802 | 19.6 |

| 30–39 | 999 | 24.4 |

| 40–49 | 967 | 23.6 |

| 50–59 | 683 | 16.7 |

| 60 or older | 644 | 15.7 |

| Education | ||

| Elementary school or less | 791 | 19.3 |

| Middle school to associate | 440 | 10.8 |

| High school to associate | 1,533 | 37.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 1,331 | 32.5 |

| Occupations | ||

| Clerk | 712 | 17.4 |

| Managers | 80 | 2.0 |

| Professionals and administrators | 750 | 18.3 |

| Service workers | 377 | 9.2 |

| Sales workers | 451 | 11.0 |

| Skilled agriculture, forestry, fishery workers | 481 | 11.7 |

| Technicians and associated workers | 450 | 11.0 |

| Craft, equipment, machine operating, assembling workers | 356 | 8.7 |

| Simple labor | 427 | 10.4 |

| Soldiers | 11 | 0.3 |

| Perceived stress | ||

| Low | 1,274 | 31.1 |

| High | 2,821 | 68.9 |

| Employment status | ||

| Standard labor | 3,494 | 85.3 |

| Precarious labor | 601 | 14.7 |

| Work hours | ||

| Daytime work hours | 3,431 | 83.8 |

| Unfixed work hours | 664 | 16.2 |

| Job demand: workload | ||

| Low | 1,590 | 38.9 |

| High | 2,505 | 61.1 |

| Job demand: emotional labor | ||

| Low | 1,507 | 36.8 |

| High | 2,588 | 63.2 |

| Job control: job autonomy | ||

| High | 988 | 24.1 |

| Low | 3,107 | 75.9 |

| Social support | ||

| High | 354 | 8.6 |

| Low | 3,741 | 91.4 |

| Depressive symptoms | ||

| Yes | 3,537 | 86.4 |

| No | 558 | 13.6 |

Differences between the depressive and non-depressive symptom groups

As shown in Table 2, compared to the non-depressive symptom group, the depressive symptom group contained more participants with precarious job (P < 0.001, Chi-square = 11.292) and more participants with unfixed work hours (P < 0.01, Chi-square = 13.310). Regarding psychosocial characteristics, compared to the non-depressive symptom group, the depressive symptom group had more participants in occupations with high job demand (workload: P < 0.001, Chi-square = 35.047; emotional labor: P < 0.001, Chi-square = 65.445) but low job control (P < 0.005, Chi-square = 11.877). In addition, the depressive symptom group had more participants who lacked social support (P < 0.001, Chi-square = 18.817).

Table 2.

Differences between the depressive symptom and non-depressive symptom groups

| Depressive symptoms |

Non-depressive symptoms |

Total |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | P-value | Chi-square | |

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Standard labor | 450 | (11.5) | 3,044 | (88.5) | 3,494 | (85.3) | 0.001 | 11.292 | |

| Precarious labor | 108 | (17.1) | 493 | (82.9) | 601 | (14.7) | |||

| Work hours | |||||||||

| Daytime work hours | 438 | (11.3) | 2,993 | (88.7) | 3,431 | (83.8) | 0.002 | 13.310 | |

| Unfixed work hours | 120 | (16.9) | 544 | (83.1) | 664 | (16.2) | |||

| Job demand | |||||||||

| Workload | Low | 278 | (10.3) | 2,227 | (89.7) | 2,505 | (61.1) | <0.001 | 35.047 |

| High | 280 | (15.7) | 1,310 | (84.3) | 1,590 | (38.9) | |||

| Emotional labor | Low | 267 | (8.6) | 2,321 | (91.4) | 2,588 | (63.2) | <0.001 | 65.445 |

| High | 291 | (18.5) | 1,216 | (81.5) | 1,507 | (36.8) | |||

| Job control | |||||||||

| Job autonomy | Low | 167 | (15.5) | 821 | (84.5) | 988 | (24.1) | 0.005 | 11.877 |

| High | 391 | (11.3) | 2,716 | (88.7) | 3,107 | (75.9) | |||

| Social support | |||||||||

| High | 483 | (11.4) | 3,258 | (88.6) | 3,741 | (91.4) | <0.001 | 18.817 | |

| Low | 75 | (21.3) | 279 | (78.7) | 354 | (8.6) | |||

Factors influencing depressive symptoms among wage workers

The moderating effects of psychosocial factors on the relationship between working conditions and depressive symptoms among wage workers were examined. The results are summarized in Table 3. After controlling for depression-related characteristics, we examined health disparities associated with gender, educational attainment, and perceived stress using the three models mentioned above. Of particular note, women were clearly at higher risk of exhibiting depressive symptoms. In addition, individuals with only an elementary school education or no education were more likely to have depressive symptoms than those with bachelor’s or graduate degrees. In addition, the group with high perceived stress was more likely to have depressive symptoms than the group with low perceived stress.

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the depressive symptom group

| Model I |

Model II |

Model III |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI |

| Working conditions | ||||||

| Employment status (reference: Standard labor) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Precarious labor | 1.66** | 1.23–2.24 | 1.79*** | 1.33–2.42 | ||

| Work hours (reference: daytime work hours) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Unfixed work hours | 1.59** | 1.16–2.18 | 1.60** | 1.17–2.21 | ||

| Psychosocial environmental factors | ||||||

| Job demand | ||||||

| Workload (reference: Low) | 1 | |||||

| High | 1.26* | 1.01–1.57 | ||||

| Emotional labor (reference: Low) | 1 | |||||

| High | 1.58*** | 1.22–2.04 | ||||

| Job autonomy (reference: High) | 1 | |||||

| Low | 1.26 | 0.93–1.71 | ||||

| Social support (reference: High) | 1 | |||||

| Low | 1.61** | 1.14–2.30 | ||||

| Working conditions × Psychosocial factors | ||||||

| Employment status × Workload (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Precarious labor × High | 1.75 | 0.88–3.48 | ||||

| Employment status × Emotional labor (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Precarious labor × High | 2.20** | 1.25–3.87 | ||||

| Employment status × Job autonomy (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Precarious labor × Low | 0.82 | 0.43–1.54 | ||||

| Employment status × Social support (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Precarious labor × Low | 1.23 | 0.42–3.60 | ||||

| Work hours × Workload (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Unfixed work hours × High | 1.02 | 0.59–1.75 | ||||

| Work hours × Emotional labor (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Unfixed work hours x High | 1.70* | 1.06–2.70 | ||||

| Work hours × Job autonomy (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Unfixed work hours x Low | 1.67 | 0.90–3.09 | ||||

| Work hours × Social support (reference: The others) | 1 | |||||

| Unfixed work hours x Low | 0.94 | 0.36–2.51 | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .128 | .205 | .195 | |||

Notes: All models are adjusted for gender, age, education, occupations, and perceived stress.

The dependent variable is depressive symptoms, the low depressive symptom group = 0 and the high depressive symptom group = 1.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

When factors related to type of employment status were added to Model I, respondents with precarious jobs were more likely to have depressive symptoms than those who had standard jobs (OR = 1.66, 95% CI = 1.23–2.24). Moreover, respondents who had flexible working hours were more likely to have depressive symptoms than respondents who had fixed daytime work hours (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.16–2.18). These results revealed both socio-demographic- and working condition-based associations with depressive symptoms. These associations were maintained when psychosocial effects were included in the model.

When psychosocial environmental factors such as job demand, job control, and social support were added to Model II, the likelihood of depressive symptoms was higher among those with high workload (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.01–1.57) and high emotional labor (OR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.22–2.04) than among those with appropriate levels of demands. When social support was added to the model as a preventive variable, the group with a low level of social support was more likely to have depressive symptoms than the group with a high level of social support (OR = 1.61, 95% CI = 1.14–2.30).

In Model III, we added interaction terms in order to identify psychosocial moderating effects on depressive symptoms. When the interaction terms of working condition and psychosocial factors were added to the model, respondents with precarious and high emotional jobs were 2.20 times more likely to have depressive symptoms than those in other groups (OR = 2.20, 95% CI = 1.25–3.87). In addition, those who had jobs with unfixed work hours involving emotionally exacting labor were 1.70 more likely to have depressive symptoms than those in other groups (OR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.06–2.70).

Discussion

Although the influence of individual characteristics on depressive symptoms has been well studied, few studies have investigated how working conditions and psychosocial determinants combined can influence depressive symptoms among wage workers. Our results showed that depressive symptoms exhibited by Korean wage workers were significantly associated with working conditions and psychosocial environmental factors even after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics. In particular, participants with precarious jobs and unfixed work hours were more likely to have depressive symptoms. Similarly, participants with high job demands, low job control, and low social support were more likely to have depressive symptoms. These results are consistent with findings of other reports,5,6 suggesting that occupational health inequality is a factor that links employment instability to poor health outcomes. These findings indicate that significant associations between key aspects of working conditions and psychosocial factors may influence depressive symptoms, thus validating the intersectional approach to examining information inequality. Our results also suggest that strengthening social support systems can be beneficial to wage workers’ mental health.

The results of our multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed several interesting points that might explain how depressive symptoms are influenced by working conditions and psychosocial environmental factors. First, with regard to working conditions, the risk of depressive symptoms was 1.66 times higher among workers with precarious jobs than those with traditional jobs. A survey conducted in Finland and Canada on working environments associated with full-time and part-time jobs found that part-time workers have higher levels of anxiety than full-time workers.44 Anxiety often goes hand in hand with depression. Furthermore, the Finnish-Canadian study reported that workers with irregular hours are 1.59 times more likely to have depressive symptoms than are daytime workers with regular hours. This is consistent with the results presented by other mental health reports.45,46 In those studies, workers with irregular hours (including night shift workers, holiday workers, and substitute workers) were exposed to harmful mental health conditions. In addition, a study showed that working more than 10 h of overtime a week was associated with a higher incidence of depression. Similarly, a previous longitudinal study suggested that health status deteriorates when employment status changes from traditional to precarious.6 Therefore, employment in non-traditional labor can result in an excessive physical burden and feelings of insecurity. This can be severe for shift workers who cannot avoid night shifts or weekend work.

Second, among psychosocial environmental factors, high job demands and a lack of control over working conditions lead to a significantly higher probability of having depressive symptoms among those with emotionally taxing jobs and excessive workloads. An excessive workload can result in physical exhaustion. Involvement in emotionally strenuous types of labor can aggravate depression.10,18,19,21 Therefore, it is essential to establish a system that can protect laborers who are engaged in emotionally strenuous labor so that a suitable workload is maintained in order to prevent excessive physical and psychological occupational demands.

Third, workers with a low level of social support are 1.61 times more likely to have depressive symptoms than are workers with a high level of support. The presence of trusting relationships among colleagues and a sense of solidarity with superiors at work protect against depression. They are important mediators that can reduce the effect of stress on depression.17,25 Hence, social support programs can be used to reduce job-related depressive symptoms. Such support programs should be developed in a way to enhance respect for workers and maintain amicable relationships among colleagues and superiors, thereby encouraging a sense of belonging to an organization.

We also found significant differences in the psychosocial factors that moderate the effects of working conditions on depressive symptoms in Korean wage workers. The results of the present study showed that those with precarious and emotionally taxing jobs were 2.20 times more likely to have depressive symptoms than other participants. In addition, participants with unfixed working hours and emotionally laborious jobs were 1.70 times more likely to have depressive symptoms than other participants. These results are consistent with the findings of Mannocci and colleagues,33 who reported that emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are associated with the mental health status of temporary workers. These results indicate that there is a need to develop programs to prevent mental illness in workers with precarious jobs in developed countries such as South Korea where labor markets are increasingly flexible.47

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as it was a cross-sectional study, we made a series of assumptions about causality based on existing theories.10,13,24,48 These assumptions should be examined further. The data can only be generalized based on longitudinal data collected from the labor market in South Korea. Second, as we used secondary data, we had access to only a single metric for the assessment of social support and depressive symptoms. Thus, there is a need to develop multidimensional assessment scales that examine various occupational psychosocial factors so that the reliability and validity of such metrics can be improved.

Conclusions

The working conditions of wage workers who have precarious jobs with unfixed work hours are linked to mental health status, including the presence of depressive symptoms. The psychosocial factors that link working conditions to depressive symptoms include job demands, job control, and social support. The present study reveals that psychosocial processes are potential moderating factors in the relationship between working conditions and depressive symptoms. The risk of depressive symptoms is high when workers have psychosocial problems and inferior working conditions.

The findings of this study support the hypothesis that psychosocial factors may play a role in promoting depressive symptoms among wage workers. Future research using multilevel analyses should be conducted to determine the combined role of individual and environmental factors such as the effect of working conditions on depressive symptoms by occupational type. Furthermore, mental health disparities among different groups of wage workers may potentially lead to disparate physical health outcomes. Therefore, in order to reduce the risk of poor mental health outcomes among wage workers, there is a need to develop mental health programs and supportive working environments in various labor markets, including those in South Korea.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Organization for Economic Coorperation and Development Sick on the job? Myths and realities about mental health at work. Paris: Organization for Economic Coorperation and Development; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization for Economic Coorperation and Development OECD employment outlook. Paris: Organization for Economic Coorperation and Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Trade Organization World Trade Organization International Trade Statistics 2013. Geneva: World Trade Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization for Economic Coorperation and Development Employment and labour market statistics, average annual hours actually worked, Hours worked. Paris: Organization for Economic Coorperation and Development; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim IH, Khang YH, Cho SI, Chun H, Muntaner C. Gender, professional and non-professional work, and the changing pattern of employment-related inequality in poor self-rated health, 1995-2006 in South Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2011;44:22–31. 10.3961/jpmph.2011.44.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung M. Health disparities among wage workers driven by employment instability in the Republic of Korea. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43:483–98. 10.2190/HS.43.3.g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korean Statistical Information Service Cause of death statistics, Intentional self-harm (suiside). Seoul: Korean Statistical Information Service; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avison WR, McLeod JD, Pescosolido BA. Mental health, social mirror. New York, NY: Springer; 2007 10.1007/978-0-387-36320-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boschman JS, van der Molen HF, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. Psychosocial work environment and mental health among construction workers. Appl Ergon. 2013;44:748–55. 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonde JP. Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:438–45. 10.1136/oem.2007.038430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chastang JF, Parent-Thirion A, Vermeylen G, Niedhammer I. Psychosocial work exposures among European employees: explanations for occupational inequalities in mental health. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015;37(3):373–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laine H, Saastamoinen P, Lahti J, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E. The associations between psychosocial working conditions and changes in common mental disorders: a follow-up study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:588–98. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munir F, Burr H, Hansen JV, Rugulies R, Nielsen K. Do positive psychosocial work factors protect against 2-year incidence of long-term sickness absence among employees with and those without depressive symptoms? A prospective study J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:3–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rugulies R, Aust B, Madsen IE, Burr H, Siegrist J, Bultmann U. Adverse psychosocial working conditions and risk of severe depressive symptoms. Do effects differ by occupational grade? Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:415–20. 10.1093/eurpub/cks071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ylipaavalniemi J, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Virtanen M, Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Vahtera J. Psychosocial work characteristics and incidence of newly diagnosed depression: a prospective cohort study of three different models. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:111–22. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tennant C. Work-related stress and depressive disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51(5):697–704. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00255-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanne B, Mykletun A, Dahl AA, Moen BE, Tell GS. Testing the job demand-control-support model with anxiety and depression as outcomes: the Hordaland Health Study. Occup Med (Lond). 2005;55:463–73. 10.1093/occmed/kqi071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PM, Bielecky A. The impact of changes in job strain and its components on the risk of depression. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:352–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rössler W. Stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in mental health workers. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(S2):65–9. 10.1007/s00406-012-0353-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahola K, Gould R, Virtanen M, Honkonen T, Aromaa A, Lonnqvist J. Occupational burnout as a predictor of disability pension: a population-based cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:284–90. 10.1136/oem.2008.038935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mutkins E, Brown RF, Thorsteinsson EB. Stress, depression, workplace and social supports and burnout in intellectual disability support staff. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2011;55:500–10. 10.1111/jir.2011.55.issue-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen SG, Benjamin H, Underwood LG. Social relationships and health. 2000 Social support measurement and intervention: a guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 1–25. 10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lange AH, Taris TW, Kompier MA, Houtman IL, Bongers PM. The very best of the millennium: longitudinal research and the demand-control-(support) model. J Occup Health Psychol. 2003;8:282–305. 10.1037/1076-8998.8.4.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen ML, Rugulies R, Christensen KB, Smith-Hansen L, Kristensen TS. Psychosocial work environment predictors of short and long spells of registered sickness absence during a 2-year follow up. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:591–8. 10.1097/01.jom.0000201567.70084.3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dagher RK, McGovern PM, Alexander BH, Dowd BE, Ukestad LK, McCaffrey DJ. The psychosocial work environment and maternal postpartum depression. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16:339–46. 10.1007/s12529-008-9014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burr H, Rauch A, Rose U, Tisch A, Tophoven S. Employment status, working conditions and depressive symptoms among German employees born in 1959 and 1965. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(6):731–41. 10.1007/s00420-014-0999-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talala K, Huurre T, Aro H, Martelin T, Prättälä R. Socio-demographic differences in self-reported psychological distress among 25- to 64-year-old Finns. Soc Indic Res. 2008;86:323–35. 10.1007/s11205-007-9153-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallance JK, Winkler EA, Gardiner PA, Healy GN, Lynch BM, Owen N. Associations of objectively-assessed physical activity and sedentary time with depression: NHANES (2005-2006). Prev Med. 2011;53:284–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammarström A, Westerlund H, Kirves K, Nygren K, Virtanen P, Hägglöf B. Addressing challenges of validity and internal consistency of mental health measures in a 27-year longitudinal cohort study - the Northern Swedish Cohort study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:4. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0099-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenström T, Elovainio M, Jokela M, Pirkola S, Koskinen S, Lindfors O, Keltikangas-Järvinen L. Concordance between Composite International Diagnostic Interview and self-reports of depressive symptoms: a re-analysis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2015;24(3):213–25. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of Empolyment and Labor Survey report on labor conditions by employment type. Seoul: Ministry of Empolyment and Labor; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannocci A, Natali A, Colamesta V, Boccia A, La Torre G. How are the temporary workers? Quality of life and burn-out in a call center temporary employment in Italy: a pilot observational study. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2014;50(2):153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Admin Sci. 1979;24:285–308. 10.2307/2392498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van der Doef M, Maes S. The Job Demand-Control (-Support) Model and psychological well-being: a review of 20 years of empirical research. Work Stress. 1999;13:87–114. 10.1080/026783799296084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1336–42. 10.2105/AJPH.78.10.1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allgöwer A, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Depressive symptoms, social support, and personal health behaviors in young men and women. Health Psychol. 2001;20:223–7. 10.1037/0278-6133.20.3.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen LR, Mortensen EL, Bech P. Prevalence of major depression and stress indicators in the Danish general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:96–103. 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talala K, Huurre T, Aro H, Martelin T, Prättälä R. Trends in socio-economic differences in self-reported depression during the years 1979-2002 in Finland. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:871–9. 10.1007/s00127-009-0009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan ZJ, Bonauto DK, Foley MP, Anderson NJ, Yragui NL, Silverstein BA. Occupation and the prevalence of current depression and frequent mental distress, WA BRFSS 2006 and 2008. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(10):893–903. 10.1002/ajim.v55.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi J, Zhang Y, Liu F, Li Y, Wang J, Flint J, et al. Associations of educational attainment, occupation, social class and major depressive disorder among Han Chinese women. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86674. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shields M. Stress and depression in the employed population. Health Rep. 2006;17:11–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Godin I, Kittel F, Coppieters Y, Siegrist J. A prospective study of cumulative job stress in relation to mental health. BMC Public Health. 2005. [cited 2014 Jan 17];5:67 41 World Health Organization. Stress at the workplace. Swiss: WHO, 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saloniemi A, Zeytinoglu IU. Achieving flexibility through insecurity: a comparison of work environments in fixed-term and permanent jobs in Finland and Canada. Eur J Indust Relat. 2007;13:109–28. 10.1177/0959680107073971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleppa E, Sanne B, Tell GS. Working overtime is associated with anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Health Study. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:658–66. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181734330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakata A. Work hours, sleep sufficiency, and prevalence of depression among full-time employees: a community-based cross-sectional study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:605–14. 10.4088/JCP.10m06397gry [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.OECD OECD Data 2015. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/emp/temporary-employment.htm [Google Scholar]

- 48.Labriola M, Lund T, Burr H. Prospective study of physical and psychosocial risk factors for sickness absence. Occup Med (Lond). 2006;56:469–74. 10.1093/occmed/kql058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]