Abstract

Most data indicates that Alzheimer’s disease involves an accumulation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) in the CNS and that sporadic cases arise from a deficiency in Aβ clearance. Considerable attention has been given to mechanisms by which Aβ might be transported between the brain and blood, and evidence suggests that p-glycoprotein, also known as the multi-drug resistance (MDR) protein (product of the ABCB1 gene), plays a role in Aβ transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). We tested this possibility through two approaches: First, wild-type and MDR1A-knockout mice were compared after intravenous injection of [125I]-labeled Aβ; after 60 min, homogenates of brain parenchyma were subjected to γ-counting of TCA-precipitable material, and histological sections of brain were subjected to autoradiography. Second, MDR1A-knockout mice were crossed with Tg2576 APP transgenic mice, a line that routinely accumulates Aβ in the brain; SDS and formic acid extracts of brain homogenates were assessed for Aβ levels by ELISA. Each of these approaches yielded data indicating that Aβ accumulates to a greater degree in mice lacking MDR1A. These findings confirm other reports linking p-glycoprotein to Aβ clearance across the BBB and have important implications for Alzheimer’s disease genetics, pharmacology, and epidemiology.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid β-peptide, blood-brain barrier, blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier, MDR1, p-glycoprotein, transport

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of age-related dementia and accounts for approximately 60 to 80 percent of all cases. Prevailing hypotheses about AD propose that amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) is at the center of the disease pathogenesis based on two major groups of data: 1) Aβ is biochemically linked to the products of three genes that cause the familial form of AD (App, Psen1, Psen2); 2) Aβ is the primary component of amyloid plaque in the brain, one of the neuropathological hallmarks of AD (1). Aβ is the proteolytic product of β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) after sequential cleavages by β- and γ-secretases (2). There are two major species of Aβ, Aβ40 and Aβ42, differing in length due to the site of the C-terminal cleavage by γ-secretase. Aβ40 is produced at an approximately 10-fold greater rate than Aβ42 in most biological systems; the former is also slower to accumulate in the brain such that its deposition generally correlates best with the presence of dementia (3). Evidence indicates that soluble Aβ is elevated in human AD brains universally and in a significant inverse correlation with synapse density (4). The net concentration of free Aβ in the brain is determined by the rate of generation, aggregation, clearance from brain, and degradation. In rare familial forms of AD, which account for less than 8% of all AD cases, elevations in total Aβ or in the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40 are caused by altered production due to mutations in the genes for APP, presenilin 1, or presenilin 2 (presenilins serve as the catalytic core of γ-secretase) (5). The vast majority of AD occur sporadically, and these appear to overwhelmingly involve impaired clearance of Aβ from the brain (6, 7).

The conjecture that impaired clearance is sufficient to cause disease implies that homeostasis of Aβ critically depends on clearance. When delivered by intracerebral injection, about two thirds of brain Aβ40 is pumped out of the brain, while one third is degraded intraparenchymally (8). There are two barriers which control efflux: the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB). There is evidence for transport of soluble Aβ across the BBB by multiple receptors/transporters. Aβ binds to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1) on the basolateral membranes of brain capillary endothelial cells (BCEC), which compose the BBB (9, 10). It appears that Aβ is subsequently pumped out of the endothelial cell and into the blood by other transporters on the apical membrane. Several lines of evidence suggests that p-glycoprotein (Pgp), the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) B1 transporter, contributes to this apical efflux and plays a critical role in Aβ clearance in normal and AD cases: lower levels of expression and transport activity of Pgp are correlated with higher levels of Aβ accumulation in the brains of older humans (11); Pgp activity is decreased in brain regions important for memory formation in AD patients (12); in a transgenic mouse model of AD, Pgp protein level is reduced, and restoring the expression of Pgp decreases Aβ accumulation (13). Compared to the BBB, little is known about how Aβ is exchanged at the BCSFB although some data suggests that choroid plexus epithelial cells (the functional component of BCSFB) also express ABC transporters such as Pgp and multidrug resistance-related protein 1 (MRP1) (14, 15).

Pgp is an ATP-dependent efflux transporter encoded by a single gene in humans (ABCB1) and two genes (Abcb1a, Abcb1b) in rodents. It is highly expressed in the apical membrane of many secretory cells such as intestine, kidney, pancreas and brain endothelium, where it serves to protect the tissues by excreting a variety of toxic xenobiotics. It also plays a crucial role in the multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype of some cancer cells. Many compounds, with a broad variety of structure and function, are known to be substrates or modulators of Pgp; the list includes pharmaceutical agents from many classes (16). Aβ has been implicated as a substrate of Pgp in in vitro cell-based transport assays (17, 18), and Aβ transport across the BBB is compromised in mice lacking both MDR1 genes (19, 20).

In the present study, we tested the ability of a single p-glycoprotein component, MDR1A (Abcb1a−/−), for sufficiency in impacting Aβ efflux from the brains of mice. Results in APPsw and MDR1A-KO mice indicated greater Aβ accumulation in the brain when MDR1A is absent. The data confirm that Pgp participates in Aβ efflux and demonstrate that the product of the MDR1A gene alone can create a deficit sufficient to elevate CNS Aβ accumulation in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Mice utilized were MDR1A-KO, their wild-type (WT) FVB counterparts, and the APPsw (Tg2576) transgenic line; all were obtained from Taconic. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System.

[125I]Aβ injections

MDR1A-KO and WT FVB were injected i.v. (tail vein) with 100 NCi of [125I]-labeled Aβ1–40. After 1 h, a fraction of the mice were anesthetized with CO2 and perfused transcardially with heparinized saline (after collection of an aliquot of cardiac blood). The brains were divided coronally at 1 mm posterior to the caudal separation of the two cerebral hemispheres. The anterior portion was stripped of meningeal tissue, homogenized in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and a protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.4) and then subjected to TCA precipitation; total protein was determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. The blood sample was diluted (15-fold) in lysis buffer and also subjected to TCA precipitation. TCA pellets were washed twice with ice-cold 5% TCA and then counted in a γ-counter. CNS cpm of each sample was normalized to its protein content and reported as a fraction of the cpm from the corresponding blood sample. Posterior portions of brains were cut into 4-mm blocks and immersion fixed in formalin. Fixed blocks were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 30-µm sections that were mounted on slides, and coated with photographic emulsion (Kodak) for autoradiography (2-day exposure). After development, sections were counterstained with H&E.

ELISA

APPsw mice were crossed with the MDR1A-KO line to generate F2 littermates carrying the APP transgene in the context of both Abcb1a−/− and Abcb1a+/+. At 6 months of age, mice were anesthetized with CO2 and perfused transcardially with heparinized saline. Brains were removed, stripped of meningeal tissue, and homogenized in RIPA buffer containing 2% SDS. The samples were subjected to centrifugation (30 min at 16,000 g), followed by incubation of those pellets for 2 h with 70% formic acid and a second centrifugation. The supernatants of each centrifugation were diluted 40-fold in binding buffer and analyzed for total Aβ by sandwich ELISA (IBL).

Statistics

Pairwise comparisons were made by Student’s t-test. Values of p less than 0.05 were taken to be significant.

RESULTS

MDR1A-dependent accumulation of [125I]-Aβ1–40 in the brain after peripheral injection

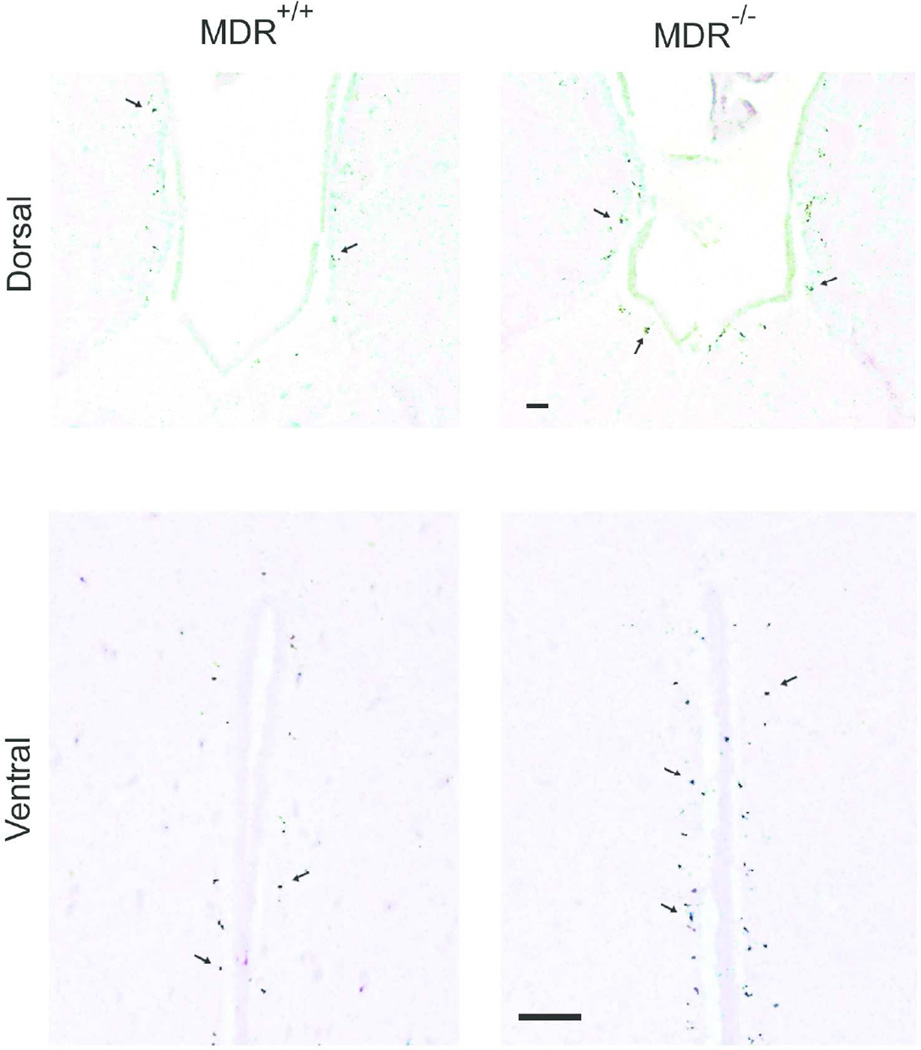

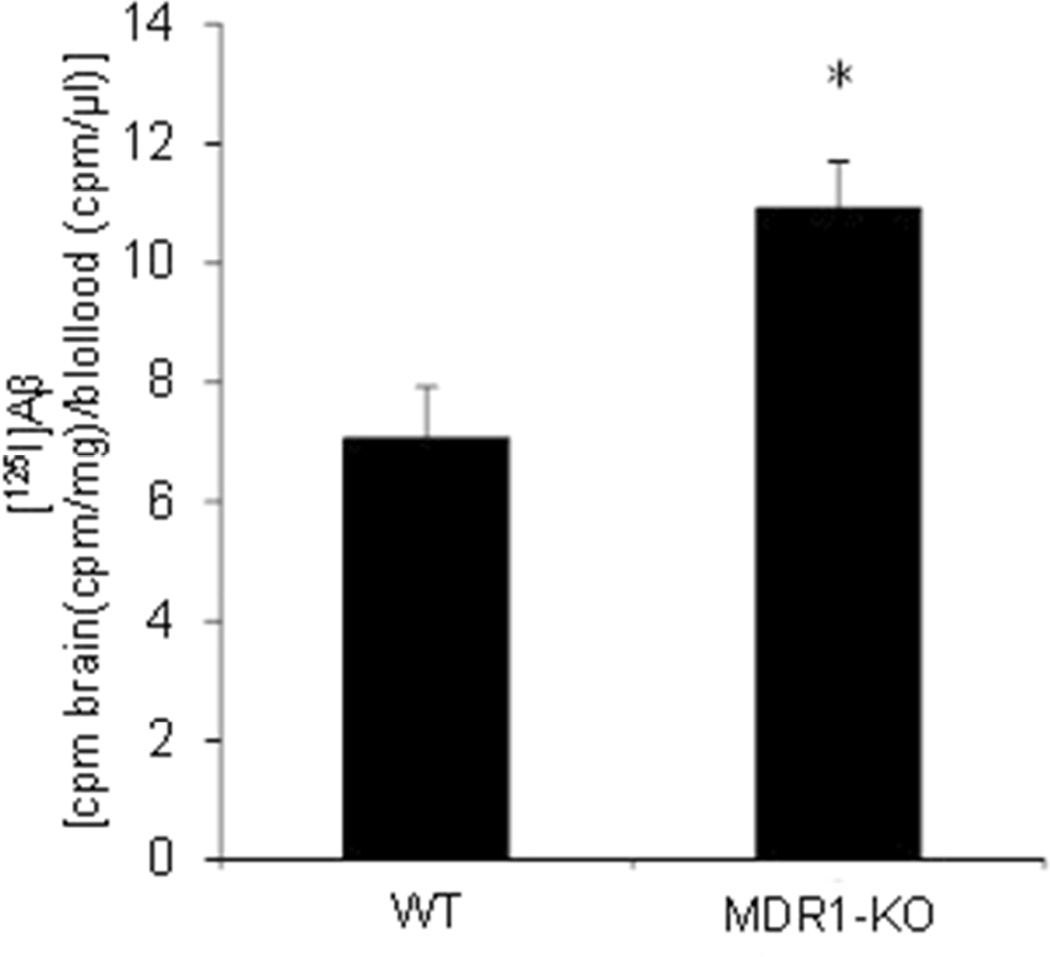

In rodents, Pgp function is carried out by two proteins: MDR1A (gene symbol: Abcb1a) and MDR1B (gene symbol: Abcb1b). To assess the consequences of a quantitative diminution in Pgp expression, we assessed mice lacking only the Abcb1a gene. Evidence indicates that Aβ flux across the BBB is bidirectional, such that plasma Aβ can equilibrate with the CNS compartment. We took advantage of this relationship to follow the partitioning of radiolabeled Aβ injected peripherally, so as to avoid disruption of the BBB through direct CNS injection. MDR1A-WT and MDR1A-KO littermates were injected via the tail vein with [125I]-labeled Aβ1–40. Aβ1–40 was selected because it is the predominant species produced in most biological systems, especially in the absence of mutations in APP or presenilins; it is also slower to aggregate than Aβ1–42 and would therefore be likely to remain monomeric throughout the handling and injections. One hour following injection, the mice were euthanized; the posterior portion of brain was processed for autoradiography, while the anterior portion was homogenized for γ-counting of TCA-precipitable material. Autoradiography showed punctate exposure in the vicinity of the third ventricle in both dorsal (above) and ventral (lower) aspects (Fig. 1); exposed silver grain densities were greater in MDR1A−/− brains compared to WT. Direct counting of γ-counting of brain homogenates indicated that MDR1A−/− brains retained more [125I]Aβ1–40 than WT (Fig. 2). These data confirm the CNS transiting of peripheral Aβ and suggest that Pgp plays a critical role in maintaining the normal equilibrium.

Figure 1. Mice devoid of MDR1A accumulate more Aβ along the third ventricle after peripheral injection.

MDR1A-KO and wild-type FVB mice were injected i.v. (tail vein) with [125I]-labeled Aβ1–40. After 1 h, the mice were euthanized and processed for autoradiography of brain slices as described under “Material and Methods”. The panels depict the detection of the label as exposed silver grains (arrows) adjacent to the third ventricle in dorsal (above) and ventral (lower) aspects of the ventricle (H&E counterstain). (Scale bar = 40 Nm)

Figure 2. Mice devoid of MDR1A accumulate more Aβ in brain homogenates after peripheral injection.

MDR1A-KO and wild-type FVB mice were injected i.v. (tail vein) with [125I]-labeled Aβ1–40. After 1 h, the mice were euthanized; brain tissue homogenates and blood were processed for TCA-precipitable counts as described under “Material and Methods”. (*p<0.05 vs. wild type)

Accumulation of endogenously produced Aβ is modulated by Pgp

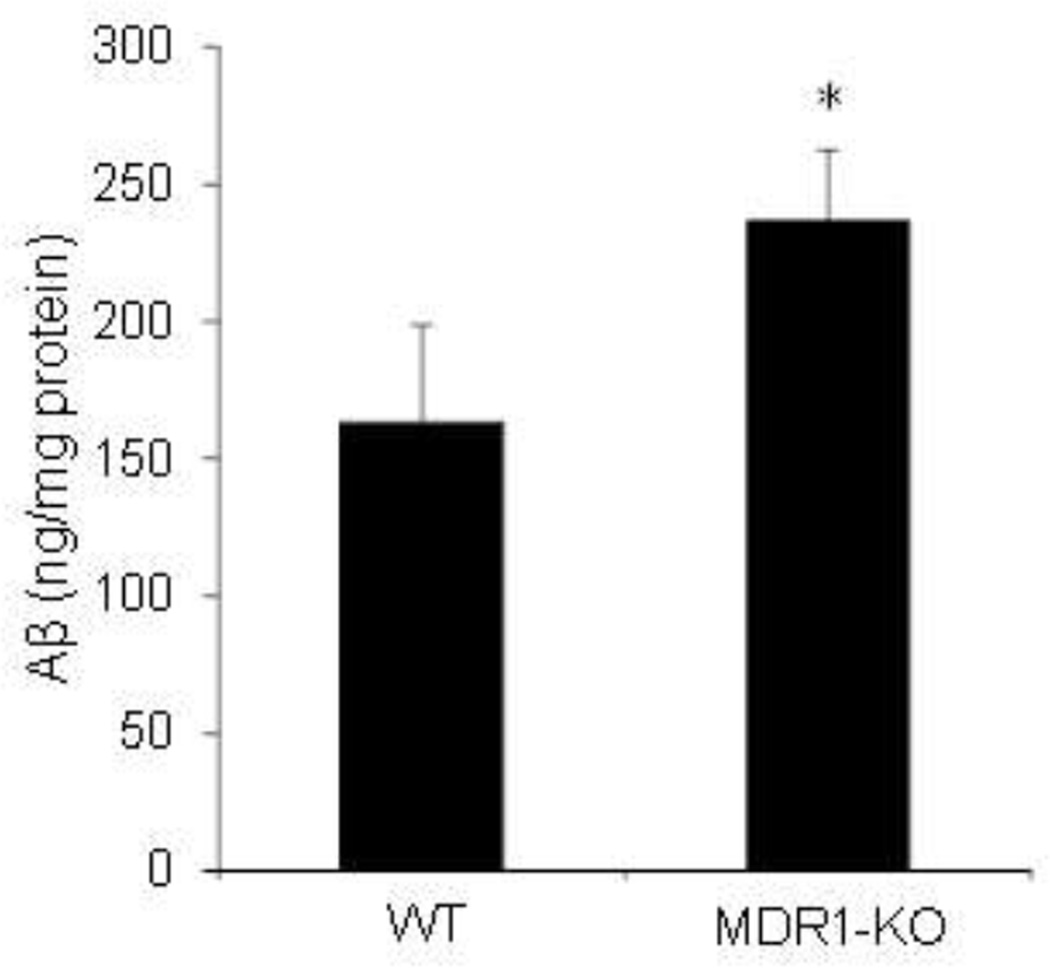

To control for caveats inherent in the delivery of radiolabeled Aβ1–40 exogenously into the periphery, we utilized a mouse model that produces considerable amounts of human Aβ in the CNS. The Tg2576 APPsw mouse is a well-established animal model of AD that overexpresses human APP bearing the Swedish mutation, thus producing high levels of Aβ in a physiological ratio of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42. This line was crossed with the MDR1A-KO line to generate mice carrying the APP transgene in the context of both MDR1A-WT and MDR1A-KO. At 6 months of age, well before the APPsw line forms visible plaques, mice were euthanized for analysis of brain Aβ levels. The homogenates were serially fractionated to analyze Aβ present in aqueous, detergent-soluble (2% SDS), or insoluble phases. In supernatants acquired from aqueous and detergent-soluble fractions APPsw/MDR1A-KO mice had higher levels of Aβ than APPsw/MDR1A-WT mice. No difference was seen in formic acid fractions between the two genotypes (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The major neuropathological hallmarks of AD are extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex. As the primary component of amyloid plaques, as well as a factor directly impacted by familial AD (FAD) gene mutations, Aβ has been the focus of most pathogenic hypotheses and a good many therapeutic strategies (21). FAD mutations that elevate Aβ production appear sufficient to cause disease, but increased Aβ production can explain only a very small number of AD cases. Therefore, faulty clearance of the peptide under normal levels of production becomes a more attractive mechanism for its brain accumulation. Indeed, sporadic AD is associated with a longer Aβ half-life in the brain (22). Recent evidence suggests that Pgp is a possible candidate participating in Aβ efflux from brain (11, 13). Highly expressed in endothelial cells, Pgp serves as the chemical component of the BBB by actively pumping out lipophilic molecules from brain. Our finding that Aβ accumulated to higher levels in the absence of the MDR1A gene confirms related evidence indicating a role for Pgp in Aβ transport.

The role of Pgp in Aβ efflux from brain was initially suggested by in vitro work with Pgp-containing membranes (18). This finding was extended by in vivo experiments wherein [125I]Aβ1–40 and [125I]Aβ1–42 were eliminated less efficiently in MDR1A/B double-knockout mice than WT mice after intracerebral injection (19). For peripherally injected Aβ1–40, it was shown that fluorescently labelled peptide accumulated more abundantly in MDR1A/B double knockout mouse brain (20). Hartz et al. (13) used a chemical inducer of Pgp expression and confirmed diminished Aβ levels, correlated with elevated antigenicity with an antibody recognizing MDR1 and −3. We used a more direct, genetic approach to test the role of MDR1A specifically: targeted ablation of the Abcb1a gene in mice with intact Abcb1b loci. As it would be expected to create a quantitative decrease in total Pgp activity, this approach may be more relevant to the quantitative reductions in Pgp expression observed during normal aging. Though expression of Abcb2 in microvessel endothelial cells from rat cerebrum has been disputed, the same study did find expression in hippocampus (23). In addition, Zhu & Liu (24) reported that the amounts of Abcb1a and Abcb1b mRNA in rat brain microvessel endothelial cells were comparable. Undoubtedly, Pgp encoded by Abcb1a at BBB, and perhaps the BCSFB, is critical for Aβ exchange between the circulation and brain. Our data demonstrate that Abcb1a deletion is sufficient to compromise Aβ clearance.

It is notable that the localization of exposed silver grains in autoradiography suggested an accumulation of [125I]Aβ1–40 adjacent to the third ventricle in both WT and KO mice. It is possible that this reflects degraded peptide or free iodine after deiodination. However, several studies indicate that significant deiodination of amino acids cannot be detected before three hours in vivo (25) Moreover, the degree of autoradiographic exposure in the relative groups mirrors rather well the differences in cpm found in TCA-precipitable counts. Other evidence from fluorescent confocal microscopy and transport assays in primary choroid plexus epithelial cells indicate that at the BCSFB Pgp is located in the subapical membrane and pumps drugs from blood to CSF (14). Considering that the surface area of the BBB is about 3 orders of magnitude greater than that of the BCSFB (26), the fact that MDR1A-knockout mouse brain accumulates more of the peripherally supplied Aβ could be due to the loss of active transport at both barriers. Active efflux at the BBB in WT mice may help to balance the passive blood-to-brain influx, especially if the brain-to-CSF efflux favored by concentration gradients is occurring at only one third of the surface area. The integrated events governing Aβ exchange between brain and blood at the BBB and BCSFB are likely to be complex. The blood-to-brain component of this exchange is worthy of exploration not only for its contribution to the equilibrium but also because some evidence suggests that at least some fraction of the Aβ naturally accumulating in the CNS could arise from peripheral sources (27).

To extend our analysis beyond peripherally administered Aβ, a human APP transgenic mouse line was examined. Mouse brain was homogenized and sequentially extracted with aqueous buffer, 2% SDS, and formic acid. Previous evidence indicates that APPsw mice do not develop obvious amyloid plaques until 8–10 months of age, and 67% of total Aβ is SDS-extractable when mice are at 6 months of age (28). This fraction represents somewhat soluble Aβ, mostly monomers and oligomers associated with lipids or other hydrophobic substances, whereas the formic acid fraction of Aβ represents insoluble peptide mostly in the fibrillar state. Our data suggest that the absence of MDR1A affects more soluble forms of Aβ primarily, which is not surprising as fibrillar Aβ would be less likely to reach the Pgp and become a substrate. Aβ treatment of murine brain endothelial cell cultures reduces Pgp expression, apparently via activation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), in concert with the NF-κB signaling pathway (29). This is confirmed by in vivo evidence showing diminution of Pgp in the BBB of APPsw mice (13). Under such conditions, the modest elevation in Aβ accumulation detected here after genetic ablation of the remaining Pgp is understandable.

The strong indications that Pgp contributes to Aβ clearance from the brain, combined with the complex regulation of its expression and activity, make it likely that considerable gains could be made in both our understanding of AD etiology and our planning of therapeutic approaches by targeting this transporter system. As an ATP-driven pump, Pgp is well-known for its wide spectrum of substrates including Aβ and many pharmacological agents such as anticancer agents, antihypertensive agents, and anti-human immunodeficiency virus agents, etc. (30). Pgp activity can be modulated by a variety of non-substrate compounds which include physiological agents such as progesterone and curcumin (30, 31) and environmental toxins such as sterigmatocystin (32). In addition to altering Pgp activity, chemicals such as steroids and xenobiotics and several physiological/pathological conditions including chronic inflammation and oxidative stress could change its mRNA and protein levels (33). Thus it is reasonable to postulate that the interactions between Pgp and various compounds under many physiological situations could potentially alter Aβ accumulation in brains and likely explain a large fraction of the environmental-exposure risk for developing AD. On the other hand, application of chemical agents which can either enhance the expression or boost the activity of Pgp may serve as a novel preventive and/or therapeutic strategy for AD.

Figure 3. Retention of brain Aβ in mice devoid of MDR1A.

APPsw mice were crossed with the MDR1A-KO line to generate mice carrying the APP transgene in the context of both MDR1A−/− and MDR1A+/+. At 6 months of age, brains were homogenized and serially fractionated with 2% SDS and formic acid. The supernatants of each fraction were analyzed for Aβ1–40 by sandwich ELISA. The figure above represents the results of the 2% SDS fraction. (*p<0.05 vs. wild type)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (2P01AG012411) and Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System Biomedical Research Foundation (1361).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the work presented here.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992 Apr 10;256(5054):184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Guhde G, Annaert W, et al. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998 Jan 22;391(6665):387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregory GC, Halliday GM. What is the dominant Abeta species in human brain tissue? A review. Neurotox Res. 2005;7(1–2):29–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03033774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, et al. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1999 Sep;155(3):853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campion D, Dumanchin C, Hannequin D, Dubois B, Belliard S, Puel M, et al. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. Am J Hum Genet. 1999 Sep;65(3):664–670. doi: 10.1086/302553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008 Jan 24;57(2):178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zlokovic BV. Clearing amyloid through the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem. 2004 May;89(4):807–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qosa H, Abuasal BS, Romero IA, Weksler B, Couraud PO, Keller JN, et al. Differences in amyloid-beta clearance across mouse and human blood-brain barrier models: kinetic analysis and mechanistic modeling. Neuropharmacology. 2014 Apr;79:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagare A, Deane R, Bell RD, Johnson B, Hamm K, Pendu R, et al. Clearance of amyloid-beta by circulating lipoprotein receptors. Nat Med. 2007 Sep;13(9):1029–1031. doi: 10.1038/nm1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibata M, Yamada S, Kumar SR, Calero M, Bading J, Frangione B, et al. Clearance of Alzheimer's amyloid-ss(1–40) peptide from brain by LDL receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. 2000 Dec;106(12):1489–1499. doi: 10.1172/JCI10498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogelgesang S, Cascorbi I, Schroeder E, Pahnke J, Kroemer HK, Siegmund W, et al. Deposition of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid is inversely correlated with P-glycoprotein expression in the brains of elderly non-demented humans. Pharmacogenetics. 2002 Oct;12(7):535–541. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deo AK, Borson S, Link JM, Domino K, Eary JF, Ke B, et al. Activity of P-Glycoprotein, a beta-Amyloid Transporter at the Blood-Brain Barrier, Is Compromised in Patients with Mild Alzheimer Disease. J Nucl Med. 2014 May 19;55(7):1106–1111. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.130161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartz AM, Miller DS, Bauer B. Restoring blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein reduces brain amyloid-beta in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Pharmacol. 2010 May;77(5):715–723. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao VV, Dahlheimer JL, Bardgett ME, Snyder AZ, Finch RA, Sartorelli AC, et al. Choroid plexus epithelial expression of MDR1 P glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein contribute to the blood-cerebrospinal-fluid drug-permeability barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Mar 30;96(7):3900–3905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi LZ, Li GJ, Wang S, Zheng W. Use of Z310 cells as an in vitro blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier model: tight junction proteins and transport properties. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008 Feb;22(1):190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller DS, Bauer B, Hartz AM. Modulation of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier: opportunities to improve central nervous system pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2008 Jun;60(2):196–209. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhnke D, Jedlitschky G, Grube M, Krohn M, Jucker M, Mosyagin I, et al. MDR1-P-Glycoprotein (ABCB1) Mediates Transport of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta peptides--implications for the mechanisms of Abeta clearance at the blood-brain barrier. Brain Pathol. 2007 Oct;17(4):347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam FC, Liu R, Lu P, Shapiro AB, Renoir JM, Sharom FJ, et al. beta-Amyloid efflux mediated by p-glycoprotein. J Neurochem. 2001 Feb;76(4):1121–1128. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cirrito JR, Deane R, Fagan AM, Spinner ML, Parsadanian M, Finn MB, et al. P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2005 Nov;115(11):3285–3290. doi: 10.1172/JCI25247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Xiong H, Callaghan D, Liu H, Jones A, Pei K, et al. Blood-brain barrier transport of amyloid beta peptides in efflux pump knock-out animals evaluated by in vivo optical imaging. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2013;10(1):13. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011 Sep;1(1):a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC, et al. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2010 Dec 24;330(6012):1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousif S, Marie-Claire C, Roux F, Scherrmann JM, Decleves X. Expression of drug transporters at the blood-brain barrier using an optimized isolated rat brain microvessel strategy. Brain Res. 2007 Feb 23;1134(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu HJ, Liu GQ. Glutamate up-regulates P-glycoprotein expression in rat brain microvessel endothelial cells by an NMDA receptor-mediated mechanism. Life Sci. 2004 Jul 30;75(11):1313–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanbury JB. Deiodination of the iodinated amino acids. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1960 Apr 23;86:417–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb42820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Lange EC. Potential role of ABC transporters as a detoxification system at the blood-CSF barrier. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004 Oct 14;56(12):1793–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutcliffe JG, Hedlund PB, Thomas EA, Bloom FE, Hilbush BS. Peripheral reduction of beta-amyloid is sufficient to reduce brain beta-amyloid: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2011 Jun;89(6):808–814. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Saido TC, Shoji M, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2001 Jan 15;21(2):372–381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park R, Kook SY, Park JC, Mook-Jung I. Abeta1–42 reduces P-glycoprotein in the blood-brain barrier through RAGE-NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1299. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou SF. Structure, function and regulation of P-glycoprotein and its clinical relevance in drug disposition. Xenobiotica. 2008 Jul;38(7–8):802–832. doi: 10.1080/00498250701867889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sreenivasan S, Ravichandran S, Vetrivel U, Krishnakumar S. Modulation of multidrug resistance 1 expression and function in retinoblastoma cells by curcumin. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013 Apr;4(2):103–109. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.110882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green AK, Barnes DM, Karasov WH. A new method to measure intestinal activity of P-glycoprotein in avian and mammalian species. J Comp Physiol B. 2005 Jan;175(1):57–66. doi: 10.1007/s00360-004-0462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauer B, Hartz AM, Fricker G, Miller DS. Modulation of p-glycoprotein transport function at the blood-brain barrier. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005 Feb;230(2):118–127. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]