Abstract

Management of chronic back pain is a challenge for physicians. Although standard treatments exert a modest effect, they are associated with narcotic addiction and serious side effects from nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents. Moreover, neurotransmitter depletion from both the pain syndrome and therapy may contribute to a poor treatment outcome. Neurotransmitter deficiency may be related both to increased turnover rate and inadequate neurotransmitter precursors from the diet, particularly for essential and semi-essential amino acids. Theramine, an amino acid blend 68405-1 (AAB), is a physician-prescribed only medical food. It contains neurotransmitter precursors and systems for increasing production and preventing attenuation of neurotransmitters. A double-blind controlled study of AAB, low-dose ibuprofen, and the coadministration of the 2 agents were performed. The primary end points included the Roland Morris index and Oswestry disability scale. The cohort included 122 patients aged between 18 and 75 years. The patients were randomized to 1 of 3 groups: AAB alone, ibuprofen alone, and the coadministration of the 2 agents. In addition, C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and plasma amino acid concentrations were measured at baseline and 28 days time points. After treatment, the Oswestry Disability Index worsened by 4.52% in the ibuprofen group, improved 41.91% in the AAB group, and improved 62.15% in the combination group. The Roland Morris Index worsened by 0.73% in the ibuprofen group, improved by 50.3% in the AAB group, and improved 63.1% in the combination group. C-reactive protein in the ibuprofen group increased by 60.1%, decreased by 47.1% in the AAB group, and decreased by 36% in the combination group. Similar changes were seen in interleukin 6. Arginine, serine, histidine, and tryptophan levels were substantially reduced before treatment in the chronic pain syndrome and increased toward normal during treatment. There was a direct correlation between improvement in amino acid concentration and treatment response. Treatment with amino acid precursors was associated with substantial improvement in chronic back pain, reduction in inflammation, and improvement in back pain correlated with increased amino acid precursors to neurotransmitters in blood.

Keywords: pain, inflammation, Theramine, AAB, medical food, amino acid, low back, ibuprofen

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis and management of back pain is a challenge for both primary care physicians and specialists. Establishing an etiology can be difficult and often problematic given treatment options that may be capable of producing serious and potentially life-threatening side effects. Treatments in some individuals often may exert a modest impact on the natural history of the condition.1–3 Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are frequently prescribed to treat chronic back pain, while they are only moderately effective in relieving pain4–7 and are associated with significant side effects. Muscle relaxants and opioid analgesics show limited efficacy and may produce sedation, constipation, or inappropriate usage. Newer antiepileptics and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors have been shown to decrease pain but have limitations. Physical therapy and other local modalities may augment treatment costs and require a considerable investment of patient time.

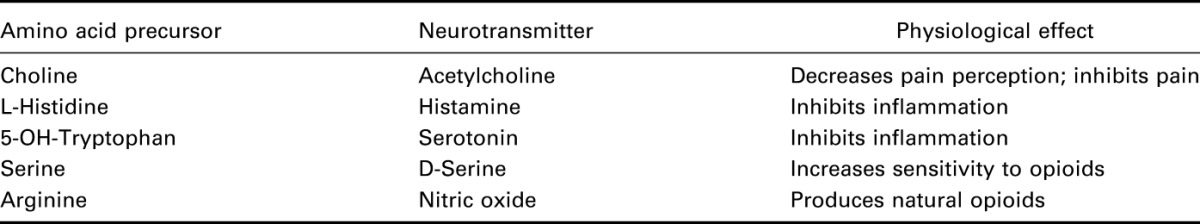

Neurotransmitter depletion8–14 and the associated synaptic fatigue15–22 may contribute to chronic pain states. Neurotransmitter depletion results from an increase in precursor turnover and dietary deficiency of the precursor.23–28 The ability to enhance neurotransmitter production associated with pain syndromes has multifactorial limits. Specifically, the unavailability of adequate essential amino acids in the diet and increased turnover rates of amino acids needed to produce neurotransmitters under such conditions.23–28 Table 1 explains how Theramine, an amino acid blend 68405-1 (AAB) addresses this unavailability. In addition, amino acids are over 99% deaminated by the liver before crossing the blood brain barrier and may not be taken up by the appropriate neuron. Once in the neuron, the adenosine brake must be released and the attenuation of effect after a couple of weeks is common. Other factors such as prolonged pharmaceutical use deplete the nerve cells of neurotransmitters.29–34

Table 1.

Neurotransmitter production from precursors.

Previous attempts35–38 to modify brain neurochemistry have focused on single neurotransmitters, such as serotonin or GABA and have not addressed the secondary issues. This approach fails to tackle the complexity of complementary neurotransmitters and their influence on patient perception of pain and suffering. AAB is a proprietary prescription medical food that concurrently enhances several neurotransmitters that are involved in pain modulation and sensation by providing neurotransmitter precursors in the form of amino acids (Table 1).41 Through a 5-step process, AAB prevents deamination by the liver, promotes uptake into the appropriate neuron, conversion to the neurotransmitter, releases the adenosine brake, and prevents the attenuation of effect. Medical foods42 are specially formulated products for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition that has distinctive nutritional requirements. Nutrient imbalances caused by pain leads to metabolic disequilibrium. The nutrients and other dietary ingredients in AAB are specifically selected and processed molecular complexes derived from foods. These components have scientifically documented properties that support the cellular or physiological activities needed to restore metabolic equilibrium, proportioned to stimulate the production of neurotransmitters in targeted cells. Clinical trials have found AAB effective in reducing and modifying pain without demonstrable side effects. AAB simultaneously stimulates the production of the neurotransmitters serotonin, GABA, nitric oxide, glutamate, and histamine.

In a previous study comparing AAB and low-dose naproxen, both the medical food group and combined therapy group (AAB with naproxen) showed statistically significant functional improvement compared with the naproxen-alone group (P < 0.05) at the 28 days time point. Furthermore, the naproxen-alone group showed significant elevations in C-reactive protein (CRP) (an acute phase marker of inflammation), alanine transaminase, and aspartate transaminase when compared with the other groups. AAB alone or in combination with naproxen showed no significant change in liver function or inflammation tests, with potentially mitigating the effects seen with naproxen alone. AAB seemed to be effective in relieving back pain without causing any significant side effects and may provide a safe alternative to presently available therapies.41

This research protocol compared AAB to a low-dose NSAID in the treatment of chronic low back pain as defined by pain lasting greater than 6 months and present on at least 5 of 7 days per week. The low-dose NSAID was used as it was not felt that the use of strictly placebo was appropriate in a chronic pain study, while the authors did not wish to expose patients to the risks associated with full dose NSAID use.

Ibuprofen is the most commonly used and most frequently prescribed NSAID.2,3 It is a nonselective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2.4 It has a prominent analgesic and antipyretic role despite its antiinflammatory properties being weaker than those of some other NSAIDs. These effects are due to the inhibitory actions on cyclooxygenases, which are involved in the synthesis of prostaglandins. Prostaglandins have an important role in the production of pain, inflammation, and fever.5 The study examined the efficacy and tolerability of AAB in patients with chronic back pain compared to ibuprofen, and the combination of ibuprofen and AAB together.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study involved 122 patients aged between 18 and 75 years in a double-blind, randomized, 3-armed trial comparing ibuprofen alone (400 mg daily), AAB alone (two 355 mg capsules twice daily), or the combined use of ibuprofen (400 mg daily) and AAB (two 355 mg capsules twice daily) for 28 days. On day 1 visit, patients were randomized to 1 of 3 groups: (1) two AAB tablets, 2 times per day, with 1 ibuprofen placebo, (2) ibuprofen (400 mg once per day), with 2 AAB placebos, 2 times per day, and (3) two AAB tablets, 2 times per day, with ibuprofen (400 mg once per day). The active and ibuprofen tablets were identical, and the active AAB and placebo capsules were identical. On days 7 and 14 visits, the evaluation of visual analog scale (VAS) and patient medication usage were completed. On day 28 visit, a Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire, an Oswestry Low Back Pain Scale, a VAS evaluation, and a patient medication usage evaluation were completed. Blood was again sampled for estimating CRP, blood count, and blood chemistries.

INCLUSION CRITERIA

Patients were identified in 8 separate clinical sites that were selected through an independent contract research organization that provides experienced investigators for clinical study selection (Table 2). Men and nonpregnant nonlactating women aged between 18 and 75 years were recruited for the study. To be included in the study, subjects were required to have back pain lasting longer than 6 weeks, with pain present on 10 of 14 days before screening. Subjects with a Roland–Morris back pain index 40 of 100 mm on the VAS were included. Subjects included must have used analgesic medication to treat pain at least 4 of last 7 days and at least 10 days in the last month before the study. Those taking an NSAID for pain had to discontinue use during a washout period based on the attached 5 half-lives of drug chart. If undergoing physical therapy for back pain, therapy had to have been stable at least 3 weeks before study and remained the same throughout study. If using psychoactive medication that might have analgesic effects (ie, antidepressants or anticonvulsants), treatment must have been stable for at least 3 months before study. Men and women of childbearing potential were required to use adequate contraception and not be pregnant or impregnate their partner during the entire duration of the study. All selected subjects were willing to commit to all clinical visits during study-related procedures, including required discontinuation washout period of analgesic or antiinflammatory medication before day 1 randomization. Finally, subjects agreed to the use of acetaminophen for rescue medication.

Table 2.

Participating research sites.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Subjects were excluded if they were not fluent in English. Subjects who underwent surgery in the previous 6 months were excluded as were subjects with neurologic impairment. Subjects with fracture of the spine within the past year and patients receiving oral, intramuscular, or soft tissue injection of corticosteroids within 1 month before screening were excluded. Subjects were not selected who used more than 325 mg of aspirin daily for nonarthritic conditions, and stability for 1 month before screening was required for any usage. Subjects were also excluded if they had a history of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, gastric or duodenal ulcer as were subjects receiving an epidural injection within the 3 months before screening. Individuals with a history of alcohol or substance abuse, uncontrolled or unstable serious cardiovascular, pulmonary, GI, or urogenital, endocrine, neurologic, or psychiatric disorder were not included. Subjects were also excluded for participation in a previous clinical trial within 1 month of screening for the present study. Finally, subjects who used controlled substances or opiate analgesics for 5 days in the month before screening were considered ineligible to participate.

RESULTS

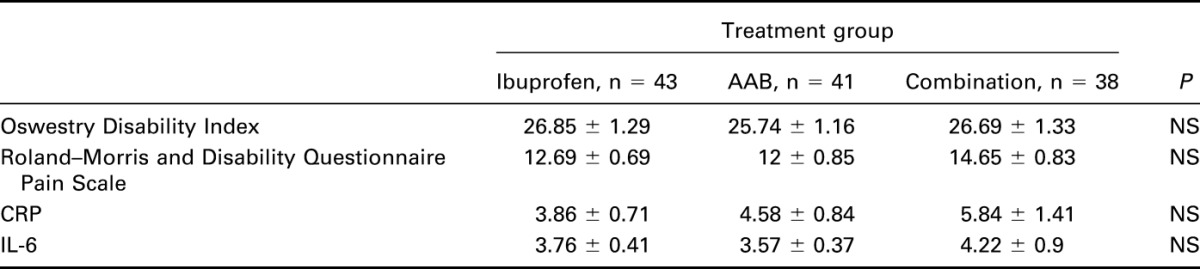

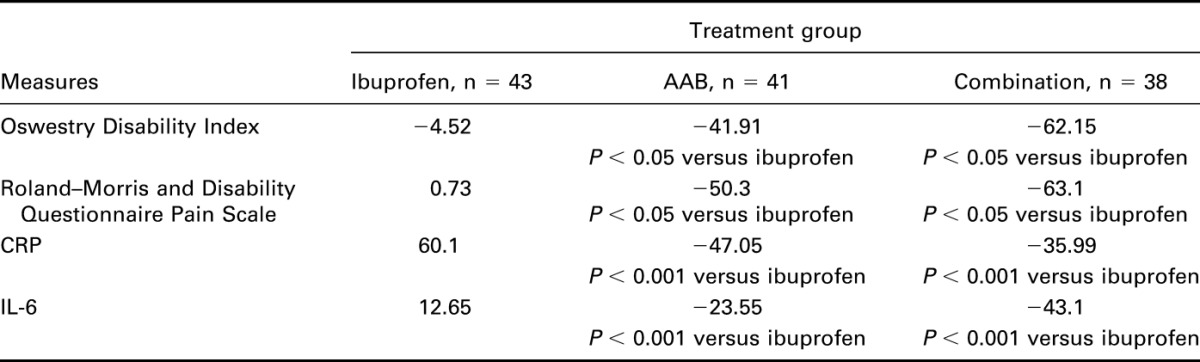

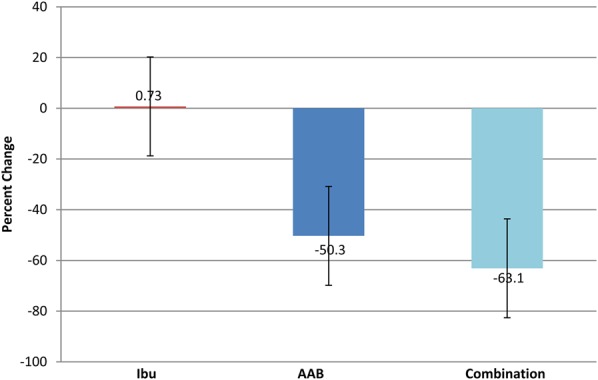

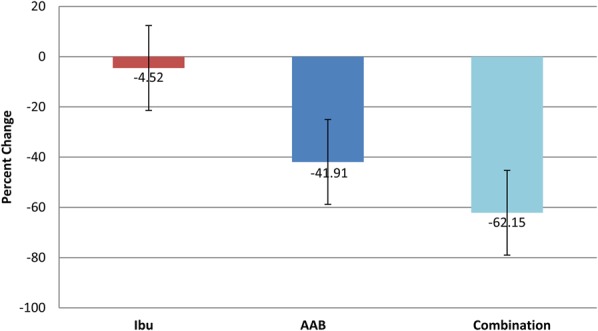

Among the 3 groups, there was no statistical difference in low back pain, inflammation, or any of the efficacy and safety variables assessed at baseline (Table 3), according to the primary end points of the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Index. At day 28 (Table 4), both the AAB group and combined therapy group (AAB with ibuprofen) pain assessment indices were considerably and statistically significantly improved compared with the ibuprofen-alone group (P < 0.05). The Roland–Morris Index fell by 63.1% (Figure 1), and the Oswestry Disability Index fell 62.15% (Figure 2) between baseline and day 28 in the AAB + ibuprofen group. In the AAB-alone group, the Roland–Morris Index fell by 50.3%, and the Oswestry Disability index fell 41.91% between baseline and day 28. Thus, if AAB was used as either primary therapy or an adjunct to ibuprofen, low back pain was significantly improved. Ibuprofen alone had no appreciable effect on chronic back pain within 28 days. Similar results were seen on using the VAS scale.

Table 3.

Baseline mean ± SD characteristics.

Table 4.

Percent change from baseline through day 28.

FIGURE 1.

Percent change in Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire Pain Scale from day 1 to day 28. Ibu n = 43, AAB n = 41, and combination n = 38. Roland Morris Disability Index fell 63.1% between baseline and day 28 in the combination therapy group, and fell 50.3% in the AAB-alone group, while there was no significant effect on chronic back pain in the ibuprofen-alone treatment group.

FIGURE 2.

Percent change in Oswestry Disability Index from day 1 to day 28. Ibu n = 43, AAB n = 41, and combination n = 38. Oswestry Disability Index fell 62.15% between baseline and day 28 in the combination therapy group, and fell 41.91% in the AAB-alone group, while there was no significant effect on chronic back pain in the ibuprofen-alone treatment group.

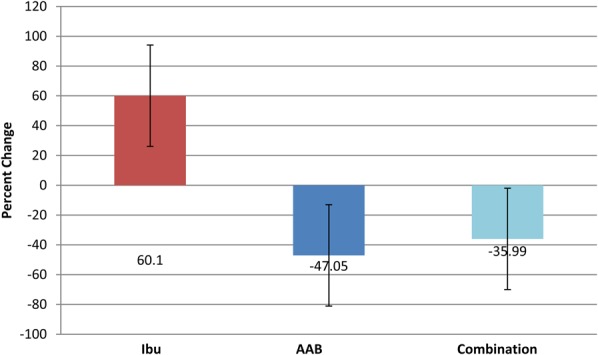

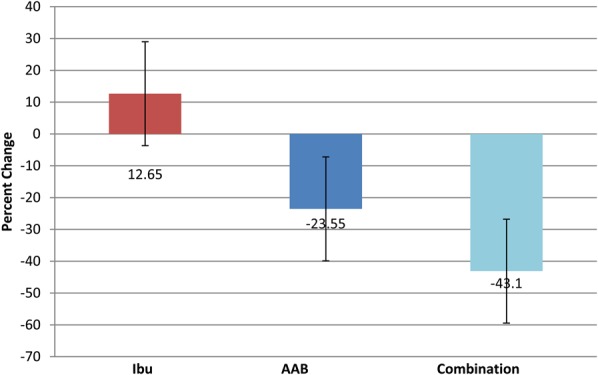

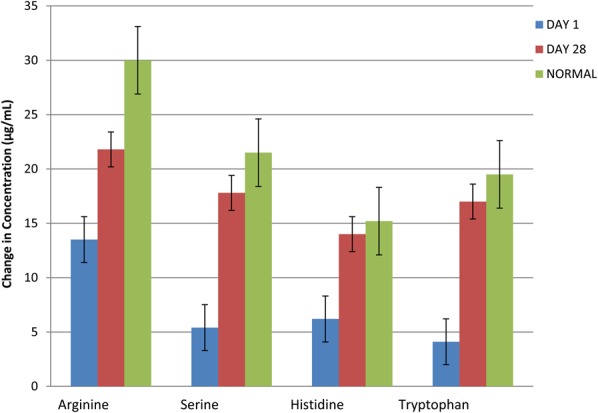

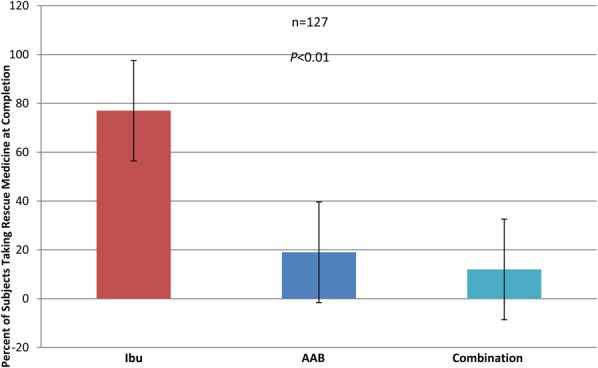

Secondary end points included CRP, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and plasma amino acid levels at day 28 compared with baseline (Figures 3, 4). In the ibuprofen-alone group, CRP rose by 60.1% (P < 0.001), and IL-6 rose by 12.65% (P < 0.001). In the AAB-alone group, the CRP level fell by 47.05% (P < 0.05), and IL-6 level fell by 23.55% (P < 0.01). In the group treated with both the AAB and ibuprofen, CRP fell 35.99% (P < 0.001), and IL-6 fell 43.1% (P < 0.001). Plasma amino acids were analyzed with liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry methodology (Figure 5). The assay had a variance of ±5%. Arginine concentration levels at day 1 were at 13.5 μg/mL, rising to 21.8 μg/mL at day 28 of the study, where normal level is 30 μg/mL. Serine concentration levels at day 1 were 5.4 μg/mL, which rose to 17.8 μg/mL at day 28 of the study, where normal is 21.5 μg/mL. Histidine concentration levels at day 1 were at 6.2 μg/mL, which rose to 14 μg/mL at day 28 of the study, where normal is 15.2 μg/mL. Tryptophan concentration levels at day 1 were at 4.1 μg/mL, which rose to 17 μg/mL at day 28 of the study, where normal is 19.5 μg/mL. Use of breakthrough medication was highly statistically significantly lower in the AAB, and the combination AAB/ibuprofen groups when compared to ibuprofen alone (Figure 6).

FIGURE 3.

Percent change in CRP from day 1 to day 28. Ibu n = 43, AAB n = 41, and combination n = 38. The CRP levels fell 35.99% for combination theory group and 47.05% for the AAB-alone group, while levels rose 60.1% for the ibuprofen-alone group.

FIGURE 4.

Percent change in IL-6 from day 1 to day 28. Ibu n = 43, AAB n = 41, and combination n = 38. The IL-6 levels fell 43.1% for combination theory group and 23.55% for the AAB-alone group, while levels rose 12.65% for the ibuprofen-alone group.

FIGURE 5.

Plasma amino acid concentrations were calculated at day 1 and day 28 in 44 of 122 patients. Plasma amino acids were analyzed using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry methodology. The assay had a variance of ±5%.

FIGURE 6.

The needed breakthrough medication usage was statistically significant in the AAB group verses the ibuprofen-alone group.

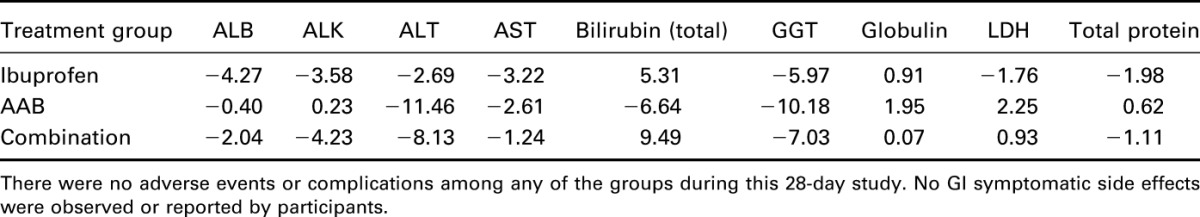

The range for normal subjects was established by ranges supplied from quest laboratories for this study. There were no adverse events or complications among any of the groups during this 28-day study (Table 5). There were no GI side effects observed in this cohort (Figure 6).

Table 5.

Percent change in blood values in all treatment groups at completion as compared with baseline.

DISCUSSION

Back pain is a common concern, affecting up to 90% of people during their lifetime. NSAIDs are the most frequently used drugs in the treatment of pain and inflammation. However, their use is limited by adverse drug side effects, notably GI toxicity. Many of the adverse effects are dose related. The current recommendation of the American Geriatrics Society is to restrict or even eliminate NSAIDs in patients, specifically when older than 65 years. This demographic has the highest incidence of osteoarthritis, back pain, and spinal stenosis. Although they are at greatest risk for adverse events, often their only alternative to NSAIDS are narcotics, which carry additional side effects and risks.

Antiinflammatory nonsteroidal drugs with nitric oxide (NO)-producing precursors (NO-NSAIDs) are a new class of drugs. These compounds have been shown to retain the antiinflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activity with reduced GI toxicity. The use of an NO moiety with an NSAID has been shown to inhibit in vitro T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.43 NO-NSAIDS have been shown to be GI protective in several models. AAB produces NO similarly to the NO-NSAIDS.43 It is interesting to note that tryptophan induces an increase in platelet aggregability, and NO production in the GI tract is known to reduce NSAID-induced mucosal erosion.

The amino acid formulation (AAB) of neurotransmitter precursors used in this study is designed to elicit neurotransmitter production of neurotransmitters that modulate nociception and inflammation.41 The precursors of serotonin, nitric oxide, histamine, and GABA are supplied in this formulation as 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), arginine, histidine, and glutamine, respectively.

To test the hypothesis that chronic back pain syndromes have an amino acid deficiency emanating from increased amino acid requirements that cannot be met by normal diet, we measured plasma amino acid concentrations at day 1 and day 28. Day 1 blood levels of amino acid neurotransmitter precursors in AAB-treated subjects were more than 2 SDs below the mean for normal subjects. Thus, in this cohort of patients with a chronic back pain syndrome, there is a deficiency of amino acid precursors in plasma that are important to neurotransmitters modulating chronic pain. Because these patients were on normal diets, study data indicate that normal diet alone cannot sustain the amino acid requirements of this chronic back pain syndrome. There do not seem to be any other studies that establish a nutrient deficiency of pain-related neurotransmitters.

Subjects who increased their amino acid blood levels in response to AAB administration over 28 days, demonstrated a reduction in pain as measured by the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, a reduction of disability symptoms as measured by the Oswestry Disability Index, and inflammation as measured by a reduction in CRP. Subjects who were treated with once a day ibuprofen did not increase their amino acid concentration, did not improve clinically, and demonstrated increased inflammation. Four of 41 subjects treated with AAB did not increase their blood concentration of amino acid, improve their clinical responses, or reduce inflammation. This may be because of minimal dosing or noncompliance.

The AAB-alone group produced a 50.3% reduction in the Roland–Morris Index and a 41.91% reduction in the Oswestry index. The AAB with 400 mg of ibuprofen administered once a day resulted in a 63.1% reduction in the Roland–Morris Index and a 62.15% reduction in the Oswestry Index. A single daily dose of 400 mg of ibuprofen had no significant effect on chronic back pain over 28 days, a nonsignificant 0.73% increase in the Roland–Morris Index measure of pain was found. Although the number of subjects was limited to 122, the differences in the data were statistically highly significant. However, since the ingredients of AAB are generally recognized as safe according to the FDA, a large safety trial is seemingly unnecessary.

This evidence is supported further by a double-blind controlled trial of a single dose naproxen and AAB for the treatment of low back pain.41 This study also indicated a reduction in pain with the Roland–Morris Index by 65%, and the Oswestry Disability Index by 61% between baseline and day 28 in the AAB + naproxen group. In the AAB-alone group, there was a significant reduction in back pain with a 32.94% on the Oswestry Disability Index and a 44% on the Roland–Morris Index. Thus, if AAB was used as either primary therapy or an adjunct to naproxen, low back pain was significantly improved. Low-dose naproxen had no significant effect on chronic back pain in 28 days. Similar results were seen on using the VAS scale.

Treating the metabolism-based nutritional deficiencies of pain syndromes could allow for the reduction of NSAID use without affecting therapeutic efficacy. Dietary management of disease is an underutilized option for patients, although it has existed for a considerable period of time. Osler44 prominently emphasized the value of nutrition in his textbooks. Tepaske et al administered an arginine-based preparation to patients before cardiac surgery.39 The clinical outcomes were found to be improved, more specifically postoperative creatinine clearance and immune function. Kalantar-Zadeh et al40 and Tepaske et al39 determined that the administration of amino acid neurotransmitter precursors in patients with congestive heart failure improved clinical outcomes. Advances in science mandate the inclusion of nutrient management of symptoms and disease.

Levels of CRP increase very rapidly in response to trauma, inflammation, and infection and decrease just as rapidly with the resolution of the condition. Thus, the measurement of CRP is widely used to monitor various inflammatory states. Baseline levels of inflammation are associated with one another and with future risk of coronary heart disease. This reduction in CRP has been demonstrated in the naproxen and AAB study as well. With CRP's association with inflammation, and subsequent involvement as a marker for heart disease, a question arises as to whether AAB may have a cardio protective application. Further investigation into this possible protective effect of AAB is warranted.

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine. In addition to its typical role in the acute phase response, IL-6 is involved in driving chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, endothelial cell dysfunction, and fibrogenesis. Because IL-6 has been associated with the generation and propagation of chronic inflammation, it was selected as a marker in the study. Proinflammatory cytokines from acute inflammation promote neutrophil build up and the release of IL-645. In the study, IL-6 followed the same pattern as CRP, with an increase in level of IL-6 in the ibuprofen-alone group (12.65%), a drop in IL-6 level in the AAB-alone group (23.55%), and a drop in the level of IL-6 in the AAB and ibuprofen group (43.1%).

There are limited data to indicate that the provision of neurotransmitter precursors alters the efficiency of pharmaceuticals. The data in this study indicate that the provision of amino acid precursors in a formulation (AAB) to facilitate neurotransmitter production results in improving the efficiency of pharmaceutical therapy. We postulate that the mechanism is related to improve intracellular metabolic function, rather than having any effect on the drug itself. This may be a new approach to a long-standing therapy.

Footnotes

William E. Shell, Stephanie Pavlik, Mira L. Breitstein, and David S. Silver are or were employees of Targeted Medical Pharma. Lawrence May was a consultant to Targeted Medical Pharma. Brandon Roth and Michael Silver have no conflicts on interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams C, Hancock MJ, Ferreira M, et al. A literature review reveals that trials evaluating treatment of non-specific low back pain use inconsistent criteria to identify serious pathologies and nerve root involvement. J Man Manip Ther. 2012;20:59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morimoto D, Isu T, Kim K, et al. Surgical treatment of superior cluneal nerve entrapment neuropathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman DM, Burke AE, Livingston EH. JAMA patient page. Low back pain. JAMA. 2013;309:1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peniston JH. A review of pharmacotherapy for chronic low back pain with considerations for sports medicine. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40:21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casazza BA. Diagnosis and treatment of acute low back pain. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, et al. Use and costs of prescription medications and alternative treatments in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in community-based settings. Pain Pract. 2012;12:550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White AP, Arnold PM, Norvell DC, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic low back pain: synthesis of the evidence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(Suppl 21):S131–S143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez LF, Kubota Y, Hu D, et al. Selective effects of dopamine depletion and L-DOPA therapy on learning-related firing dynamics of striatal neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4782–4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mette C, Zimmermann M, Grabemann M, et al. The impact of acute tryptophan depletion on attentional performance in adult patients with ADHD. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCall T, Weil ZM, Nacher J, et al. Depletion of polysialic acid from neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM) increases CA3 dendritic arborization and increases vulnerability to excitotoxicity. Exp Neurol. 2013;241:5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coull JT, Hwang HJ, Leyton M, et al. Dopamine precursor depletion impairs timing in healthy volunteers by attenuating activity in putamen and supplementary motor area. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16704–16715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyamoto H, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Hamada K, et al. Serotonergic integration of circadian clock and ultradian sleep-wake cycles. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14794–14803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemaire N, Hernandez LF, Hu D, et al. Effects of dopamine depletion on LFP oscillations in striatum are task- and learning-dependent and selectively reversed by L-DOPA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18126–18131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croxson PL, Browning PG, Gaffan D, et al. Acetylcholine facilitates recovery of episodic memory after brain damage. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13787–13795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lnenicka GA, Atwood HL. Impulse activity of a crayfish motoneuron regulated its neuromuscular synaptic properties. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer RF. Neuromuscular transmission in single motor units in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 1982;5:S46–S49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stalberg E. Clinical electrophysiology in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:622–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serra A, Ruff RL, Leigh RJ. Neuromuscular transmission failure in myasthenia gravis: decrement of safety factor and susceptibility of extraocular muscles. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1275:129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lotrich FE, El-Gabalawy H, Guenther LC, et al. The role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of depression: different treatments and their effects. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2011;88:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ablin JN, Buskila D, Van HB, et al. Is fibromyalgia a discrete entity? Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enoka RM, Baudry S, Rudroff T, et al. Unraveling the neurophysiology of muscle fatigue. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2011;21:208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wen G, Hui W, Dan C, et al. The effects of exercise-induced fatigue on acetylcholinesterase expression and activity at rat neuromuscular junctions. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2009;42:137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bongiovanni R, Kyser AN, Jaskiw GE. Tyrosine depletion lowers in vivo DOPA synthesis in ventral hippocampus. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;696:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coppola A, Wenner BR, Ilkayeva O, et al. Branched-chain amino acids alter neurobehavioral function in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E405–E413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crockett MJ, Apergis-Schoute A, Herrmann B, et al. Serotonin modulates striatal responses to fairness and retaliation in humans. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3505–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demjaha A, Murray RM, McGuire PK, et al. Dopamine synthesis capacity in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1203–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong XY, Azzam MM, Rao W, et al. Evaluating the impact of excess dietary tryptophan on laying performance and immune function of laying hens reared under hot and humid summer conditions. Br Poult Sci. 2012;53:491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernstrom JD. Effects and side effects associated with the non-nutritional use of tryptophan by humans. J Nutr. 2012;142:2236S–2244S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adell A. Antidepressant properties of substance P antagonists: relationship to monoaminergic mechanisms? Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2004;3:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold LM, Jain R, Glazer WM. Pain and the brain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asakura M, Nagashima H, Fujii S, et al. [Influences of chronic stress on central nervous systems]. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2000;20:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bano S, Gitay M, Ara I, et al. Acute effects of serotonergic antidepressants on tryptophan metabolism and corticosterone levels in rats. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2010;23:266–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barkan T, Hermesh H, Marom S, et al. Serotonin uptake to lymphocytes of patients with social phobia compared to normal individuals. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barton DA, Esler MD, Dawood T, et al. Elevated brain serotonin turnover in patients with depression: effect of genotype and therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wurtman RJ. Precursor control of neurotransmitter synthesis. Pharmacol Rev. 1980;32:315–335. Ref Type: Generic. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Javitt DC. The role of excitatory amino acids in neuropsychiatric illness. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;2:44–52. Ref Type: Generic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caston JC. Clinical applications of L-tryptophan in the treatment of obesity and depression. Adv Ther. 1987;4:78–80. Ref Type: Generic. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blum K. Enkephalinase inhibition and precursor amino acid loading improves inpatient treatment of alcohol and polydrug abusers. Alcohol. 1989;5:481–493. Ref Type: Generic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tepaske R, Velthuis H, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, et al. Effect of preoperative oral immune-enhancing nutritional supplement on patients at high risk of infection after cardiac surgery: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Anker SD, Horwich TB, et al. Nutritional and anti-inflammatory interventions in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:89E–103E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shell WE, Charuvastra EH, DeWood MA, et al. A double-blind controlled trial of a single dose naproxen and an amino acid medical food theramine for the treatment of low back pain. Am J Ther. 2012;19:108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan SL, Baggott JE. Medical foods: products for the management of chronic diseases. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng H. Effects of nitric oxide-releasing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NONO-NSAIDs) on melanoma cell adhesion. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;264:161–166. Epub August 4, 2012. Ref Type: Generic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osler W. The Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. New York, NY: Appleton and Company; 1892. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dos Santos SA. Comparative analysis of two low-level laser doses on the expression of inflammatory mediators and on neutrophils and macrophages in acute joint inflammation. Lasers Med Sci. 2013. Ref Type: Generic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]