Abstract

We report the case of an otherwise healthy 28-year-old-man who presented with a first-time seizure. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a circumscribed left frontal lobe heterogeneous mass most consistent with a neoplasm. He underwent left supraorbital craniotomy with mass resection of the lesion, with histopathology of the brain tissue revealing heightened cellularity with perivascular neutrophilic predominance and neutrophils percolating through the brain parenchyma and surrounding cortical neurons, most consistent with a diagnosis of early cerebritis. He completed six weeks of empiric antimicrobial therapy with resolution of his seizures. Early cerebritis, which was elegantly demonstrated on histopathology in this case, is an uncommon diagnosis as patients typically present later with progressive disease and signs and symptoms reflective of an underlying brain abscess.

Keywords: early cerebritis, cerebritis, brain abscess, seizure

Introduction

Brain abscesses are uncommon events, with an incidence of 0.4 to 0.9 cases per 100,000 persons, and can be caused by a number of pathogens, including bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, and parasites1. Factors predisposing to brain abscesses include underlying immunosuppression (i.e. immunodeficiency from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or immunosuppressive medications), direct extension from neurosurgical procedures, contiguous spread from an otogenic or odontogenic source, paranasal sinus disease, or a systemic source of infection such as endocarditis or bacteremia that hematogenously spreads to the brain1.

The evolution of brain abscess formation is divided into four stages based on histological criteria. Early cerebritis, which occurs within the first one to three days after infection, is the first stage2. An evolving brain abscess at this early stage can be very difficult to diagnose given a lack of symptoms and localizing physical exam findings. We report the case of a young man who presented to our hospital with a sentinel seizure secondary to early cerebritis.

Case Report

A 28-year-old man was admitted to our hospital after a witnessed first-time tonic-clonic seizure that occurred at home while sleeping. Emergency Medical Services (EMS) was called, and upon arrival he was noted to be disoriented and post-ictal. En route to the hospital he suffered another tonic-clonic seizure and was given diazepam with termination of seizure activity. He had no significant medical problems aside from recurrent Streptococcus throat infections as a child. He did note a painful pustule in his left nare that he had “picked at” the week prior, but denied recent headache, focal neurologic symptoms, fevers, chills, sweats, sinus congestion, sinus drainage, ear pain, sore throat, cough, or shortness of breath.

On admission to our hospital, clinical exam revealed no focal neurologic abnormalities and he had no evidence of otogenic or odontogenic infection. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 14.9 (4.0 – 10.0 1000/mm3) with a slight lymphocytic predominance of 54% (19 – 53%). HIV rapid antibody test was negative.

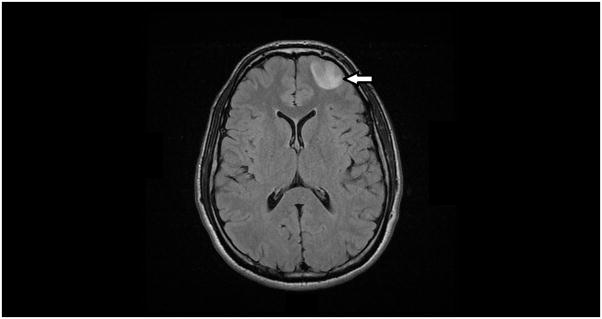

About one hour after his initial seizure he underwent computed tomography (CT) imaging that revealed a mildly heterogeneous hypoattenuating lesion in the left frontal lobe, followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his brain, which showed a 2.8 × 2.2 × 2.1 cm circumscribed left frontal lobe heterogeneous mass most consistent with a neoplasm (Figure 1). There were no findings concerning for acute or subacute ischemia on MRI.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain showing a 2.8 × 2.2 × 2.1 cm left frontal lobe lesion.

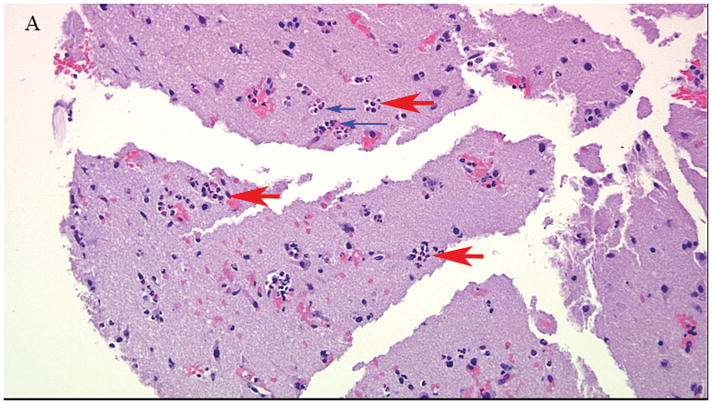

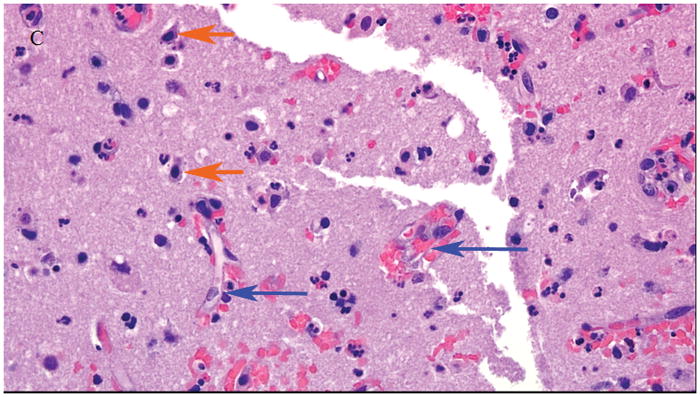

The morning of hospital day two he underwent left supraorbital craniotomy with mass resection of the lesion. Intraoperative brain tissue was sent for frozen pathology. While no neoplastic cells were seen, microscopic examination was performed. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained microscopic sections of the neocortex and subcortical white matter showed heightened cellularity with perivascular neutrophilic predominance with neutrophils percolating through the brain parenchyma, and surrounding cortical neurons (Figure 2). There were no neoplastic cells visualized. In some areas where brain parenchyma was infiltrated by neutrophils there was evidence of necrosis with staining pallor, microvacuolization, and hypereosinophilic neuronal necrosis (Figure 3), raising the possibility of acute infarction rather than early cerebritis. A Gram’s stain was performed on the tissue but no organisms were identified. He was treated intra-operatively with intravenous cefazolin, and given the findings on tissue histopathology the Infectious Diseases Service was consulted post-craniotomy. Antimicrobial therapy was broadened empirically to include intravenous vancomycin (1g IV every 6 hours), cefepime (2g IV every 8 hours), and metronidazole (500mg IV every 8 hours). Anti-epileptic therapy was also initiated with levetiracetam. Intraoperative tissue was sent for aerobic and anaerobic culture, which were both negative for growth. No other tissue cultures were sent.

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of the neocortex and subcortical white matter. Perivascular neutrophils (large red arrows) within and exiting blood vessels (small blue arrows) at 20x magnification.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of the neocortex and subcortical white matter. Acute neuronal necrosis (short orange arrows) with shrunken and darker-appearing neuronal nuclei with surrounding blood vessels (long blue arrows) at 40x magnification

He was afebrile and clinically stable throughout the remainder of his hospitalization and discharged on hospital day 4 on ceftaroline (600mg IV every 12 hours) and metronidazole (500mg PO three times daily). Repeat MRI of his brain five weeks after discharge showed some residual area concerning for persistent cerebritis, but he continued to do well without any neurologic or systemic infectious symptoms. His metronidazole was stopped after 28 days and his ceftaroline after completing a 42-day antibiotic course. Repeat MRI of the brain five-and-a-half weeks later showed residual enhancement in the region of the resection but otherwise stable findings. He continues to do well clinically with no seizure recurrence. He continues to be followed as an outpatient by the Neurosurgery and Neurology services and is still on levetiracetam (375mg PO twice daily). The plan is to repeat a brain MRI in 01/2017 and taper off the levetiracetam if the findings are stable.

Discussion

Brain abscesses are classified based on both histopathologic and brain imaging findings with either CT scan or MRI and fall into four stages. The first stage, early cerebritis, occurs from days 1–3 and is characterized by a poorly demarcated inflammatory response in the affected tissue with neutrophil accumulation, tissue necrosis, and edema. On brain imaging this appears as an irregular area of low density which may or may not enhance with contrast. The second stage, late cerebritis, occurs from days 4–9, with macrophage and lymphocytic infiltration predominating. Fibroblasts appear on the margin and lay down a reticulin matrix, the precursor of collagen. This area often appears larger on brain imaging with ring enhancement after contrast is given. In the third stage or early capsule, angiogenesis occurs with increased fibroblast migration around the necrotic center and mature collagen formation in some areas of the developing capsule. Imaging of the brain shows a developing capsule with clear ring enhancement after contrast is given. In the last stage, or late capsule, a collagen capsule surrounds the necrotic center with a zone of gliosis surrounding it. The capsule is well visualized as a faint ring on brain imaging, with a thicker dense ring seen after contrast is given3–4.

Cerebritis and subsequent brain abscesses develop in response to infection from pyogenic bacteria, beginning as a localized area of cerebritis and evolving into a well-circumscribed abscess surrounded by a vascularized, fibrotic capsule. These infections typically result from either contiguous spread of bacteria from otogenic or odontogenic sources, direct extension from neurosurgical procedures or penetrating head trauma, or via hematogenous spread from other sources such as bacteremia or endocarditis5. In about 30% of cases no obvious etiology for infection can be determined6. Except in infants, brain abscesses are almost never sequelae from meningitis6.

The most common causative organisms are Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, with viridans streptococci and Stapylococcus aureus the most common pathogens7, although a wide variety of gram negative and anaerobic bacteria have also been implicated8. In cases of infection secondary to neurosurgical procedures or head trauma, infection is often caused by skin-colonizing bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, or gram-negative bacteria. When contiguous spread from the sinuses, mastoids, or middle ears are the source, Streptococcus species are common, although anaerobic and gram-negative bacteria can also be the causative agents1. In patients who are immunocompromised and develop brain abscesses, other pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, fungi from Aspergillus or Candida species, parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii, or bacteria from the genera Nocardia or Actinomyces9 can also be the cause. Fungi are the causative agent in 90% of brain abscesses among solid-organ transplant patients1. Empiric antimicrobial therapy targeting the most likely pathogens should be initiated following biopsy, and if the source is unknown antimicrobial therapy with vancomycin, metronidazole, and a third generation cephalosporin is typically most appropriate10.

The diagnosis of cerebritis is difficult as patients typically do not come to medical attention until they are symptomatic, which often does not occur until the formation of an abscess. Clinical manifestations can include a non-localizing headache, fever, altered consciousness, and seizure, although these signs are often absent and can evolve subtly over days to weeks. Seizures occur in up to 40% of patients with brain abscesses, and fever is present in less than one-half of cases6. Focal neurologic signs are present in about 50% of patients and are dependent on the location of the abscess6. Diagnosis is most often made based on findings from CT scan or MRI of the brain. Cultures of blood and cerebrospinal fluid identify the causative agent in about 25% of cases1.

Neurosurgical intervention with stereotactic biopsy or abscess drainage is often necessary to identify the causative pathogen. Stereotactic aspiration should strongly be considered, especially if purulent material is present in the center of the abscess on imaging. If brain imaging does not identify a central cavity in the abscess, careful consideration should be given to between stereotactic biopsy and empiric antimicrobial administration with follow-up imaging of the brain1.

In a review of a recent case series of brain abscesses, Gram’s stain and culture of brain tissue were only diagnostic 58–81% of the time11. Despite a negative Gram’s stain and culture in our patient, we were confident in our diagnosis of early cerebritis and felt the most likely etiology of cerebritis was metastatic seeding of his left frontal lobe via venous drainage from the pustule in his nare, which would be most consistent with a Staphylococcus aureus infection.

Lastly, in our patient there was concern of acute infarction rather than early cerebritis based on the tissue findings on histopathology. In animal model studies of rat’s post-transient arterial occlusion, neuronal death occurred as early as 2 hours, with progressive neuronal damage occurring over the initial 12 hours after the ischemic event. Conversely, the earliest influx of neutrophils occurred more slowly, beginning around 12 hours after the ischemic insult and peaking around 72 hours12–13. In our patient findings on histopathology showed predominantly neutrophilic infiltration with only rare neuronal necrosis, favoring early cerebritis over ischemic injury.

We felt this case was particularly noteworthy given the elegant findings of early cerebritis on histopathology, which is an uncommon diagnosis as patients typically present later with progressive disease and signs and symptoms reflective of an underlying brain abscess.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter Kobalka from the Department of Pathology at the University of California, San Diego for kindly providing photographs of the histopathology sections for this case.

Support: The primary author is supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, McKhann GM, II, et al. Brain Abscess. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):447–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1301635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt RH, Enzmann DR, Yeager AS. Neuropathologic and computerized tomographic findings in experimental brain abscess. J Neurosurg. 1981;55(4):590–603. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.4.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britt RH, Enzmann ER. Clinical stages of human brain abscesses on serial CT scans after contrast infusion. J Neurosurg. 1983;59(6):972–89. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.6.0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kielian T. Immunopathogenesis of brain abscesses. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arlotti M, Grossi P, Pea F, et al. Consensus document on controversial issues for the treatment of infections of the central nervous system: bacterial brain abscesses. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(Suppl 4):S79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernardini GL. Diagnosis and management of brain abscesses and subdural empyema. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4(6):448–56. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouwer MC, Coutinho JM, van de Beek D. Clinical characteristics and outcome of brain abscess: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82(9):806–813. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathisen GE, Meyer RD, George WL, et al. Brain Abscess and Cerebritis. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6(Supp 1):S101–S6. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.supplement_1.s101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subhojit R, Ellenbogen JM. Seizures, Frontal Lobe Mass, and Remote History of Periodontal Abscess. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(6):805–806. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-805-SFLMAR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roos KL, Tunkel AR. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark RK, Lee EV, Fish CJ, et al. Development of tissue damage, inflammation and resolution following stroke: An immunohistochemical and quantitative planimetric study. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31(5):565–72. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90124-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang RL, Chopp M, Chen H, et al. Temporal profile of ischemic tissue damage, neutrophil response, and vascular plugging following permanent and transient (2H) middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Neurol Sci. 1994;125:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]