Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to examine the associations between daily physical activity (DPA), handgrip strength, appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASMM) and physical performance (balance, gait speed, chair stands) with quality of life in prefrail and frail community-dwelling older adults.

Methods

Prefrail and frail individuals were included, as determined by SHARE-FI. Quality of life (QoL) was measured with WHOQOL-BREF and WHOQOL-OLD, DPA with PASE, handgrip strength with a dynamometer, ASMM with bioelectrical impedance analysis and physical performance with the SPPB test. Linear regression models adjusted for sex and age were developed: In model 1, the associations between each independent variable and QoL were assessed separately; in model 2, all the independent variables were included simultaneously.

Results

Eighty-three participants with a mean age of 83 (SD: 8) years were analysed. Model 1: DPA (ß = 0.315), handgrip strength (ß = 0.292) and balance (ß = 0.178) were significantly associated with ‘overall QoL’. Balance was related to the QoL domains of ‘physical health’ (ß = 0.371), ‘psychological health’ (ß = 0.236), ‘environment’ (ß = 0.253), ‘autonomy’ (ß = 0.276) and ‘social participation’ (ß = 0.518). Gait speed (ß = 0.381) and chair stands (ß = 0.282) were associated with ‘social participation’ only. ASMM was not related to QoL. Model 2: independent variables explained ‘overall QoL’ (R 2 = 0.309), ‘physical health’ (R 2 = 0.200), ‘autonomy’ (R 2 = 0.247) and ‘social participation’ (R 2 = 0.356), among which balance was the strongest indicator.

Conclusion

ASMM did not play a role in the QoL context of the prefrail and frail older adults, whereas balance and DPA were relevant. These parameters were particularly associated with ‘social participation’ and ‘autonomy’.

Keywords: Frailty, Quality of life, Muscle mass, Handgrip strength, Balance

Background

In community-dwelling older adults, the geriatric syndrome of frailty is common [1]. Frailty is defined as a state of high vulnerability and is caused by malnutrition, chronic inflammation and sarcopenia [2], which is a progressive loss of muscle mass in combination with a decrease in muscle strength or physical performance [3].

The consequences of frailty are adverse health outcomes such as disability, dependency, hospitalisation and need for long-term care [2]. Furthermore, when compared to robust community-dwelling persons, frail adults demonstrate significantly lower quality of life (QoL) [4–7]. Since sufficient energy, freedom from pain and the ability to perform the activities of daily living are important factors influencing QoL [8], it can be assumed that disabilities, physical limitations and deterioration of psychological well-being are possible explanations for the poorer QoL of frail adults [4, 5].

There is evidence that low daily physical activity (DPA) is associated with poor QoL in older adults [9, 10]. Furthermore, previous studies of frail persons have demonstrated that muscle strength, as represented by handgrip strength [3], plays an important role regarding QoL [6, 7, 11]. Since muscle mass is an important prerequisite for muscle strength [12], it is clear that there is also an association between muscle mass and QoL. To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has observed this relationship in prefrail and frail adults. However, some studies have showed that not only loss of muscle mass but also muscle quality (e.g. muscle composition, metabolism, neural activation, fibrosis) contributes to the age-related decline in physical performance and mobility [13–15]. The link between physical performance and QoL in frail adults has been demonstrated in previous research. Accordingly, an association between slowness (assessed by gait speed or the Timed Up and Go test) and QoL has been shown [6, 11]. Furthermore, Gobbens et al. [7] revealed that, in addition to handgrip strength, difficulties in maintaining balance and difficulties in walking are associated with poor QoL in frail adults living in nursing homes.

Since frailty is a public health challenge [16], and the number of frail persons is expected to increase in the future [1], it is of particular importance to better understand the factors associated with poor QoL. Thus, the aim of this analysis was to examine the associations between DPA, handgrip strength, appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASMM), physical performance and the different QoL domains in prefrail and frail older persons still living in their own homes.

Methods

Study sample

Data for this cross-sectional analysis were derived from the baseline assessment of a randomised controlled intervention study, conducted between September 2013 and July 2015 in Vienna, Austria. The study protocol has been previously published [17]. In this study, persons older than 65 years, who were still living in their own homes, were included. These persons had to be prefrail or frail according to the Frailty Instrument for primary care of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE-FI) [18]. SHARE-FI is a sex-specific calculator that includes items concerning exhaustion, weight loss, handgrip strength, slowness and low activity. SHARE-FI is based on discrete factor scores, and it divides persons into robust (female <0.315; male <1.212 points), prefrail (female <2.103; male <3.005 points) and frail (female <6; male <7 points). As prefrail and frail persons were included, females had to score more than 0.315 points and males more than 1.212 points, respectively. In addition, adults at risk of malnutrition or persons who were malnourished according to the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form (MNA®-SF ≤ 11 points) were included [19]. As only one participant in the main study was at risk of malnutrition without being at least prefrail, we excluded this person from the present cross-sectional study to harmonise the sample. Furthermore, since the data were baseline data from a randomised trial, participants had to be willing to be visited at home by trained lay volunteers twice a week to perform six strength exercises and talk about nutrition-related aspects [17]. Persons with impaired cognitive function according to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE < 17 points), insufficient German language skills, chemo- or radiotherapy at the moment or planned, insulin-treated diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage III or IV and patients with chronic kidney insufficiency with protein restriction or on dialysis were excluded. Persons living in nursing homes or retirement housing were also not allowed to participate in the study.

Measurements

The following measurements were taken at participants’ homes by members of the study team (sports and nutritional scientists). Due to impaired vision, all items of the questionnaires were read aloud to the participants.

Daily physical activity (DPA)

The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) [20] was used to assess DPA. This is a validated questionnaire for persons over 55 years [21], which includes items concerning: (1) time spent sitting; (2) time spent walking outdoors; and (3) time spent on light, (4) moderate and (5) strenuous sports [20]. In addition, the following yes or no questions concerning household activity were asked: (6) light household tasks; (7) exhausting household tasks; (8) repair work; (9) light gardening; (10) exhausting gardening; and (11) caregiving activities. In order to analyse the questionnaire, these 11 items were multiplied by a weight score dependent on the level of exhaustion. Finally, all the items were summed. The range of possible scores was from 0 (worst score) to 360 (best score) [20].

Appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASMM)

Body composition was assessed with phase-sensitive bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA 2000-S device; Data input®, Darmstadt, Germany). For this purpose, participants were placed in a supine position and four electrodes were attached to each person’s dominant hand and foot [22]. An alternating current was then passed through the body to measure resistance (R) and reactance (Xc) [23]. ASMM was calculated using the validated formula of Sergi et al. [24]:

Handgrip strength

Handgrip strength was measured with a hydraulic dynamometer (Jamar®, Lafayette, Louisiana) following the standard procedure [25]. Accordingly, participants were placed in a sitting position on a chair, with their forearms on the arms of the chair and their wrists over the end. The thumb was placed facing upwards. After a short demonstration, each participant performed three attempts on each side, alternating between the right and left hand. Between each attempt, there was a break of 1 min. Finally, the highest value of all six measurements was taken and analysed.

Physical performance (balance skills, gait speed, chair stands)

Physical performance was assessed with the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) test [26]. This test is subdivided into three categories, namely, balance skills, gait speed and chair stands. Balance was assessed using side-by-side, semi-tandem and tandem stands. If the first two tasks were possible, participants scored 1 point; if a tandem stand was possible for <3 s, 0 points were given; if a tandem stand was possible for >9 s, participants scored 2 points. Gait speed was tested with a single 4-m walk, with or without assistive devices such as a wheeled walker. Results were divided into four categories (not possible = 0 points; >8.7 s = 1 point; 8.70–6.21 s = 2 points; 6.20–4.82 s = 3 points; <4.82 s = 4 points). The ability to rise from a chair and return to seated position five times with arms crossed was also tested. These results were again divided into four categories (not possible or <60 s = 0 points; >16.7 s = 1 point; 16.69–13.70 s = 2 points; 13.69–11.20 s = 3 points; <11.19 s = 4 points). Finally, a performance score was calculated, summing all the results. The range of possible scores was from 0 (worst) to 12 (best performance).

Quality of life (QoL)

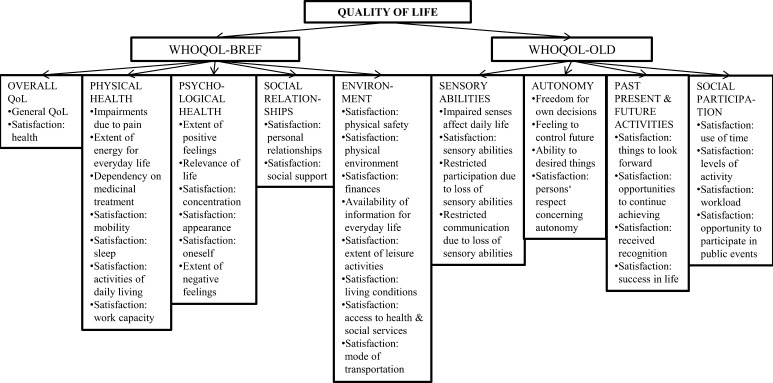

The German version of the World Health Organisation Quality of Life-BREF assessment (WHOQOL-BREF) [16], an abbreviated, cross-culturally validated version of WHOQOL-100 [27], was used to assess QoL. The assessment consists of 26 items with a five-point Likert scale response format. The first two questions assess the ‘overall QoL’ of the past 2 weeks, whereas the remaining questions assess QoL in four different domains: ‘physical health’ (seven items), ‘psychological health’ (six items), ‘social relationships’ (three items) and ‘environment’ (eight items). According to the standard procedure [28], all the domains were scored and transformed into a scale ranging from 0 to 100, where a lower value indicates a lower QoL. The ‘social relationships’ domain was calculated using two instead of three items, because only eight participants replied to the question ‘How satisfied are you with your sex life?’

In addition to WHOQOL-BREF, the following four domains of the German version of the World Health Organisation Quality of Life-OLD assessment (WHOQOL-OLD) [29] were added: ‘sensory abilities’ (four items), ‘autonomy’ (four items), ‘past, present and future activities’ (four items) and ‘social participation’ (four items). All the QoL domains used in this study and a brief description of their components are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Used domains of WHOQOL-BREF and WHOQOL-OLD and a brief description of their components

Further measurements

Age, education level (‘elementary school or no degree’, ‘secondary school’, ‘university entrance diploma or higher degree’) and comorbidities were recorded. In addition, each participant’s medication was also documented. Furthermore, body mass index (kg/m2) was calculated by dividing the body weight (kg) (as measured by a calibrated scale) by the squared body height (m2) (which was measured with a tape).

Statistical analysis

Based on a median split, study participants were divided into ‘low overall QoL’ (≤ 40 points) and ‘high overall QoL’ (>40 points). Group differences in the continuous variables were assessed by t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests, depending on the distribution. For group differences in the categorical variables, Chi-square tests were used, and in the case of the group being smaller than five persons, Fisher’s exact tests were applied. Whenever an item of WHOQOL-BREF or WHOQOL-OLD was missing, the mean of the other items belonging to this domain was calculated [28]. This was undertaken in all domains except for ‘social relationships’, which was calculated with two instead of three items. As a measure of reliability, the internal consistency was determined for each single domain of WHOQOL-BREF and WHOQOL-OLD using Cronbach’s alpha. Furthermore, the correlations between the included independent variables were analysed using Spearman’s or Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to determine the associations between the included variables and QoL. In the first model, a single variable was included as an independent variable, adjusted for age and sex. In the second model, we wanted to identify the strongest indicator for each QoL domain. We also examined how these variables explained each QoL domain. Thus, we undertook a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis including all the variables (DPA, handgrip strength, ASMM, balance skills, gait speed, chair stands). However, we only included variables with a p value threshold of 0.20. As in model 1, model 2 was adjusted for sex and age by entering these variables in the models irrespective of their significance. For all the statistical analyses, IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, U.S.) was used. All the tests were two-sided, and a p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In total, 482 people were screened for eligibility, 285 of them in hospitals. Since 208 inpatient individuals close to discharge did not meet the inclusion criteria, 54 refused participation and 19 were excluded for other reasons, only four subjects were recruited in the hospitals. The remaining 80 subjects were recruited via the media: 197 people responded to two editorial features, 47 did not meet the inclusion criteria, 34 refused participation after being provided with detailed project information and 37 were not included for other reasons. Finally, 29 prefrail and 54 frail participants (86 % women) were included in this analysis. Characteristics of the study sample are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample based on a median split of the ‘overall quality of life’ variable

| Total (n = 83) | Low overall quality of life (≤40 points) (n = 47) | High overall quality of life (>40 points) (n = 36) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 82.6 (8.1) | 81.4 (8.4) | 84.2 (7.5) | 0.115 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 86 % | 87 % | 84 % | 0.617 |

| Male | 14 % | 13 % | 16 % | |

| Living arrangement | ||||

| Alone | 75 % | 74 % | 75 % | 0.956 |

| With others | 25 % | 26 % | 25 % | |

| Education | ||||

| Elementary school or no degree | 53 % | 72 % | 53 % | 0.150 |

| Secondary school | 35 % | 40 % | 45 % | |

| University entrance diploma or higher degree | 12 % | 8 % | 22 % | |

| Frailty status (score) | 2.83 (1.1) | 3.18 (0.9) | 2.36 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Prefrail | 35 % | 19 % | 56 % | 0.001 |

| Frail | 65 % | 81 % | 44 % | |

| Nutritional status (score) | 26.4 (2.8) | 25.9 (3.1) | 27.1 (2.3) | 0.071 |

| Normal nourished | 43 % | 45 % | 61 % | 0.032 |

| At risk of malnutrition | 33 % | 40 % | 39 % | |

| Malnourished | 8 % | 15 % | 0 % | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.1 (4.5) | 27.3 (4.6) | 26.9 (4.5) | 0.724 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardiac insufficiency | 17 % | 15 % | 28 % | 0.149 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4 % | 2 % | 6 % | 0.576 |

| Hypertension | 60 % | 74 % | 69 % | 0.612 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 14 % | 23 % | 6 % | 0.020 |

| Chronic rheumatism | 7 % | 15 % | 0 % | 0.015 |

| WHOQOL-BREF domains | ||||

| Overall quality of life | 43.1 (16.5) | 32.3 (12.4) | 57.2 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Physical health | 47.7 (16.7) | 42.3 (14.1) | 54.7 (17.4) | 0.001 |

| Psychological health | 61.6 (16.0) | 54.7 (14.3) | 70.5 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| Social relationships | 74.4 (21.7) | 74.2 (22.6) | 74.7 (20.8) | 0.923 |

| Environment | 75.0 (12.3) | 71.3 (12.8) | 79.9 (8.9) | 0.001 |

| WHOQOL-OLD domains | ||||

| Sensory abilities | 48.0 (22.6) | 46.6 (24.0) | 49.9 (20.8) | 0.517 |

| Autonomy | 53.6 (14.9) | 49.5 (15.3) | 59.1 (12.5) | 0.003 |

| Past, present and future activities | 54.3 (12.8) | 51.4 (12.1) | 58.1 (12.9) | 0.021 |

| Social participation | 43.7 (12.8) | 37.8 (11.1) | 51.4 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity parameters | ||||

| Daily physical activity (score) | 13.6 (0.0–125.6) | 13.6 (0.0–80.0) | 28.8 (0.0–125.9) | 0.009 |

| Appendicular skeletal muscle mass (kg) | 16.9 (3.4) | 16.5 (3.3) | 17.4 (3.3) | 0.274 |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 16.8 (7.2) | 15.2 (7.6) | 18.9 (6.2) | 0.023 |

| Short physical performance battery (score) | 4.9 (2.8) | 4.3 (2.6) | 5.6 (2.9) | 0.039 |

| Balance skills (score) | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.2) | 0.008 |

| Gait speed (score) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.1) | 0.551 |

| Chair stands (score) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.381 |

The data are presented in mean (standard deviation) or median (minimum–maximum) or percentages

Group differences: Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data, t test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data

Using Cronbach’s alpha, the internal consistency was determined for each single domain: ‘overall QoL’ (α = 0.662), ‘physical health’ (α = 0.673), ‘psychological health’ (α = 0.658), ‘social relationships’ (α = 0.580), ‘environment’ (α = 0.624), ‘sensory ability’ (α = 0.919), ‘autonomy’ (α = 0.640), ‘past, present and future activities’ (α = 0.636) and ‘social participation’ (α = 0.491).

The correlation coefficients within the included independent variables are shown in Table 2. Accordingly, DPA was found to be associated with balance skills, gait speed and chair stand, but not with handgrip strength and ASMM. The strongest significant correlation was found between DPA and balance skills. Furthermore, a moderate association between handgrip strength and ASMM was identified along with a weak association between handgrip strength and chair stands. In Table 3, the associations between each independent variable and the QoL domains, adjusted for sex and age, are presented. In this regard, DPA was found to be significantly associated with ‘overall QoL’ as well as with ‘physical health’, ‘psychological health’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘social participation’. Handgrip strength was found to be significantly related to ‘overall QoL’. Balance skills was found to be associated with ‘overall QoL’ and the QoL domains of ‘physical health’, ‘psychological health’, ‘environment’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘social participation’. Gait speed and chair stands were found to be related to ‘social participation’ only.

Table 2.

Correlations between included independent variables

| Daily physical activity | Handgrip strength | Appendicular skeletal muscle mass | Balance skills | Gait speed | Chair stands | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | |

| Daily physical activity | 0.188 | 0.089 | 0.213 | 0.066 | 0.498 | <0.001 | 0.343 | 0.002 | 0.297 | 0.006 | ||

| Handgrip strength | 0.188 | 0.089 | 0.446 | <0.001 | 0.164 | 0.138 | 0.207 | 0.051 | 0.217 | 0.048 | ||

| Appendicular skeletal muscle mass | 0.213 | 0.066 | 0.446 | <0.001 | 0.138 | 0.152 | −0.071 | 0.542 | 0.054 | 0.648 | ||

| Balance skills | 0.498 | <0.001 | 0.164 | 0.138 | 0.152 | 0.193 | 0.470 | <0.001 | 0.566 | <0.001 | ||

| Gait speed | 0.343 | 0.002 | 0.207 | 0.061 | −0.071 | 0.542 | 0.470 | <0.001 | 0.503 | <0.001 | ||

| Chair stands | 0.297 | 0.006 | 0.217 | 0.048 | 0.054 | 0.648 | 0.566 | <0.001 | 0.503 | <0.001 | ||

n = 83

Pearson’s correlation coefficient for normally distributed data and Spearman’s correlation coefficient for data that are not normally distributed

Significant results are shown in bold

Table 3.

Model—linear regression models including one independent variable (e.g. handgrip strength) and one QoL domain (dependent variable), adjusted for sex and age

| Daily physical activity | Handgrip strength | Appendicular skeletal muscle mass | Balance skills | Gait speed | Chair stands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHOQOL-BREF | ||||||

| Overall QoL | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.129 | 0.272 | 0.089 | 0.366 | 0.151 | 0.158 |

| Standardised ß | 0.315 | 0.292 | 0.138 | 0.178 | 0.068 | 0.070 |

| p value | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.352 | 0.001 | 0.179 | 0.160 |

| Physical health | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.114 | 0.039 | 0.073 | 0.162 | 0.048 | 0.229 |

| Standardised ß | 0.310 | −0.077 | 0.137 | 0.371 | 0.121 | 0.138 |

| p value | 0.009 | 0.540 | 0.357 | 0.001 | 0.287 | 0.225 |

| Psychological health | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.063 | 0.015 | 0.031 | 0.245 | 0.009 | 0.010 |

| Standardised ß | 0.259 | 0.096 | 0.144 | 0.236 | 0.030 | 0.045 |

| p value | 0.038 | 0.456 | 0.354 | 0.043 | 0.799 | 0.702 |

| Social relationships | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.003 |

| Standardised ß | −0.041 | 0.014 | −0.022 | 0.137 | 0.107 | 0.004 |

| p value | 0.742 | 0.911 | 0.884 | 0.234 | 0.354 | 0.975 |

| Environment | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.049 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.088 | 0.047 | 0.030 |

| Standardised ß | 0.160 | 0.026 | 0.087 | 0.253 | 0.143 | 0.048 |

| p value | 0.187 | 0.836 | 0.568 | 0.024 | 0.207 | 0.676 |

| WHOQOL-OLD | ||||||

| Sensory ability | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.120 | 0.116 | 0.059 | 0.116 | 0.138 | 0.117 |

| Standardised ß | 0.071 | −0.022 | −0.017 | 0.006 | −0.154 | −0.036 |

| p value | 0.542 | 0.852 | 0.908 | 0.955 | 0.155 | 0.740 |

| Autonomy | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.099 | 0.095 | 0.002 | 0.123 | 0.084 | 0.055 |

| Standardised ß | 0.244 | 0.237 | 0.088 | 0.276 | 0.184 | −0.063 |

| p value | 0.049 | 0.058 | 0.589 | 0.015 | 0.106 | 0.583 |

| Past, present and future activities | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.124 | 0.021 | 0.010 |

| Standardised ß | 0.090 | −0.058 | −0.009 | 0.090 | −0.117 | 0.042 |

| p value | 0.508 | 0.674 | 0.956 | 0.584 | 0.344 | 0.741 |

| Social participation | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.202 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.267 | 0.150 | 0.087 |

| Standardised ß | 0.478 | 0.088 | 0.109 | 0.518 | 0.381 | 0.282 |

| p value | <0.001 | 0.484 | 0.466 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.013 |

n = 83

Significant results are shown in bold

According to the multiple linear regression analysis (Table 4), DPA, handgrip strength and balance skills together explained 31 % of the variance in ‘overall QoL’. Furthermore, balance skills alone explained 20 % of the QoL domain of ‘physical health’. DPA, handgrip strength and balance skills were independent indicators for the QoL domain of ‘autonomy’ (R 2 = 0.247), whereas balance was the strongest indicator. Moreover, DPA and balance skills together explained 36 % of the variance in the QoL domain of ‘social participation’, and balance again showed the strongest association.

Table 4.

Model—multiple linear regression model including all independent variables (e.g. handgrip strength) and one QoL domain (dependent variable), adjusted for sex and age

| R 2; p value | Included independent variablesa | Standardised | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHOQOL-BREF | ||||

| Overall QoL | 0.309; p < 0.001 | Daily physical activity | 0.274 | 0.027 |

| Handgrip strength | 0.345 | 0.004 | ||

| Balance skills | 0.180 | 0.125 | ||

| Physical health | 0.200; p = 0.001 | Balance skills | 0.389 | 0.001 |

| Psychological health | 0.073; p = 0.160 | Balance skills | 0.246 | 0.044 |

| Social relationships | 0.002; p = 0.940 | |||

| Environment | 0.052; p = 0.284 | Balance skills | 0.205 | 0.087 |

| WHOQOL-OLD | ||||

| Sensory ability | 0.059; p = 0.114 | |||

| Autonomy | 0.247; p = 0.004 | Daily physical activity | 0.192 | 0.152 |

| Handgrip strength | 0.285 | 0.029 | ||

| Balance skills | 0.333 | 0.014 | ||

| Past, present and future activities | 0.004; p = 0.895 | |||

| Social participation | 0.356; p < 0.001 | Daily physical activity | 0.299 | 0.012 |

| Balance skills | 0.418 | <0.001 | ||

n = 83

aOnly variables with a p value threshold of 0.20 were included

Discussion

The main findings indicated that there was no association between skeletal muscle mass and QoL, whereas balance skills, DPA and handgrip strength were associated with QoL. Furthermore, balance was the factor most strongly associated with the QoL domains of ‘physical health’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘social participation’.

Before discussing the associations, it ought to be mentioned that when compared to previous trials, our participants scored similar values in the QoL domains, except for ‘social relationships’, ‘environment’ and ‘physical health’ [30, 31]. The higher scores in the ‘social relationship’ domain might be explained by the fact that we excluded the question ‘How satisfied are you with your sex life?’ Higher scores in the ‘environment’ domain might be explained by the different environmental circumstances of the countries. Lower scores in the ‘physical health’ domain might be traced back to the fact that we only included prefrail and frail persons, i.e. persons with defined physical limitations.

The correlation between handgrip strength and QoL is in accordance with other studies [6, 32, 33]. As handgrip strength is an overall measurement of body strength in older adults [34, 35], our results indicate that muscle strength is an important factor for QoL, whereas muscle mass is not. Hence, muscle quality and factors such as muscle composition, neural activation, metabolism and fibrosis might be relevant [13–15]. Our findings also revealed that balance was the variable most strongly associated with the various QoL domains. An association between balance and poorer QoL was also described by Gobbens et al. [7]. This relationship might be due to the fact that balance is the most important requirement in daily life [36], and problems in maintaining balance lead to a restriction of activities due to the fear of falling [37]. In this context, it is noteworthy that muscle strength and muscle mass are important biomechanical requirements for maintaining balance [38]. However, in our sample, neither muscle strength nor muscle mass was found to be associated with balance skills. The nonsignificant correlation is comparable to the findings of Visser et al. [34] and a British study [39]. A reduction in the association between muscle strength and balance over the lifespan has also been confirmed in the current literature [40], with a change in the neuromuscular components being identified as the underlying reason [40]. Misic et al. [41] showed that muscle quality and not muscle mass was the strongest independent factor for balance in older adults. However, apart from muscle quality, limitations in the sensory system (visual, vestibular, proprioceptive, tactile somatosensory), cognitive impairments and orthopaedic problems also influence balance [36, 38]. Hence, the data indicate that it is not muscle mass, but rather factors such as muscle quality, constraints in the sensory system and orthopaedic problems that are closely linked to QoL in prefrail and frail persons. Further research on this assumption is needed.

As previous studies have showed, ‘social participation’ and contact with neighbours are important factors for the well-being and mental health of older persons [42, 43]. As the recent study of Etman et al. [44] showed that limited ‘social participation’ is associated with further worsening of frailty symptoms, this QoL domain is of special interest. Our data showed that individuals with better DPA and balance skills have a better QoL in ‘social participation’, indicating that balance and DPA should be kept as high as possible. However, it could also be the other way around: QoL in the ‘social participation’ domain should be increased to enhance balance and DPA. Apart from this, the fact that good balance is an essential precondition for leaving the house and for participating in social activities might be the reason for the close association. The same considerations might also apply to the QoL domain of ‘autonomy’.

A major strength of our study was the inclusion of very old community-dwelling prefrail and frail subjects. We used reliable and valid measurements to assess variables such as muscle mass, DPA and QoL. One limitation to the study design was that a temporal and causal link between independent variables and QoL could not be proven. The small sample size was another limitation. Nevertheless, we were able to detect the effects of the physical training and nutritional intervention carried out by the trained lay volunteers. However, the internal consistency was lower than in other validation studies [45, 46]. Hence, an acceptable internal consistency of >0.70 [47] was only achieved in the ‘sensory ability’ domain. However, the domain scores were sufficient for the study purpose, as the correlation between the items in each domain was adequate. Nevertheless, these questionnaires should be validated for prefrail and frail persons in further research. Moreover, ASMM was calculated based on the results of the bioelectrical impedance analysis using the validated formula of Sergi et al. [24], who validated the ASMM calculation for individuals with a mean age of 71.4 years (SD: 5.4) without chronic comorbidities. Due to this fact, this formula might not be directly comparable to our study participants since our population was both older and had chronic comorbidities.

Conclusion

As skeletal muscle mass was neither associated with ‘overall QoL’ nor with any QoL domain, skeletal muscle mass can be considered as not playing a role in the QoL context of prefrail and frail older persons. However, balance skills and DPA are relevant factors. These parameters were particularly associated with the QoL domains of ‘social participation’ and ‘autonomy’. However, we do not know whether low balance skills and low DPA are the cause or the consequence of low QoL.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (Grant Number: LS12-039). The authors would like to thank Martin Oberbauer for his assistance in conducting the study, Georg Heinze for the support in statistical issues, Maria Luger for the critical reading and Mark Ackerley for the professional proofreading of the paper.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local ethical committee of the Medical University of Vienna (Ref: 1416/2013) and the local ethical committee of the city of Vienna (Ref: EK13-240-1113). Additionally, the study complied with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Santos-Eggimann B, Cuenoud P, Spagnoli J, Junod J. Prevalence of frailty in middle-aged and older community-dwelling Europeans living in 10 countries. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009;64(6):675–681. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2004;59(3):255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in older people. Age and Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilotta C, Bowling A, Case A, Nicolini P, Mauri S, Castelli M, et al. Dimensions and correlates of quality of life according to frailty status: A cross-sectional study on community-dwelling older adults referred to an outpatient geriatric service in Italy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masel MC, Graham JE, Reistetter TA, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ. Frailty and health related quality of life in older Mexican Americans. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CC, Li CI, Chang CK, Liu CS, Lin CH, Meng NH, et al. Reduced health-related quality of life in elders with frailty: A cross-sectional study of community-dwelling elders in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gobbens RJ, Luijkx KG, van Assen MA. Explaining quality of life of older people in the Netherlands using a multidimensional assessment of frailty. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(8):2051–2061. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Arnal JF, Bautmans I, Beaudart C, Bischoff-Ferrari H, et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcified Tissue International. 2013;93(2):101–120. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9758-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meneguci J, Sasaki JE, Santos A, Scatena LM, Damiao R. Sitting Time and quality of life in older adults: A population based study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2015 doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenkranz RR, Duncan MJ, Rosenkranz SK, Kolt GS. Active lifestyles related to excellent self-rated health and quality of life: Cross sectional findings from 194,545 participants in The 45 and Up Study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1071. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang YW, Chen WL, Lin FG, Fang WH, Yen MY, Hsieh CC, et al. Frailty and its impact on health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study on elder community-dwelling preventive health service users. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e38079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLean RR, Kiel DP. Developing consensus criteria for sarcopenia: An update. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2015;30(4):588–592. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis E, Litwic A, Cooper C, Dennison E. Determinants of muscle and bone aging. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2015;230(11):2618–2625. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGregor RA, Cameron-Smith D, Poppitt SD. It is not just muscle mass: A review of muscle quality, composition and metabolism during ageing as determinants of muscle function and mobility in later life. Longevity and Healthspan. 2014;3(1):9. doi: 10.1186/2046-2395-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt M, Schwartz AV, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: The health, aging and body composition study. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61(10):1059–1064. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckinx F, Rolland Y, Reginster J-Y, Ricour C, Petermans J, Bruyère O. Burden of frailty in the elderly population: Perspectives for a public health challenge. Archives of Public Health. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0068-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorner TE, Lackinger C, Haider S, Luger E, Kapan A, Luger M, et al. Nutritional intervention and physical training in malnourished frail community-dwelling elderly persons carried out by trained lay “buddies”: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1232. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero-Ortuno R, Walsh CD, Lawlor BA, Kenny RA. A frailty instrument for primary care: Findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) BMC Geriatrics. 2010;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salva A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF) Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56(6):M366–M372. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.6.M366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): Development and evaluation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1993;46(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Washburn RA, McAuley E, Katula J, Mihalko SL, Boileau RA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): Evidence for validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52(7):643–651. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Data Input (2009). Das B.I.A.-Kompendium 3. Ausgabe. Darmstadt. http://www.data-input.de/media/pdfdeutsch/Kompendium_III_Ausgabe_2009.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2015.

- 23.Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gomez JM, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis–part I: Review of principles and methods. Clinical Nutrition. 2004;23(5):1226–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sergi G, De Rui M, Veronese N, Bolzetta F, Berton L, Carraro S, et al. Assessing appendicular skeletal muscle mass with bioelectrical impedance analysis in free-living Caucasian older adults. Clinical Nutrition. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, Patel HP, Syddall H, Cooper C, et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: Towards a standardised approach. Age and Ageing. 2011;40(4):423–429. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angermeyer, M., Kilian, R., & Matschinger, H. (2000). WHOQOL-100 und WHOQOL-BREF. Handbuch für die deutschsprachige Version der WHO Instrumente zur Erfassung von Lebensqualität. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- 28.World Health Organisation (1996). WHOQOL-BREF Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment. Geneva, Switzerland.

- 29.Winkler I, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. The WHOQOL-OLD. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie. 2006;56(2):63–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas-Carrasco R, Laidlaw K, Power MJ. Suitability of the WHOQOL-BREF and WHOQOL-OLD for Spanish older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2011;15(5):595–604. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.548054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campos AC, e Ferreira EF, Vargas AM, Albala C. Aging, gender and quality of life (AGEQOL) study: Factors associated with good quality of life in older Brazilian community-dwelling adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Dennison EM, Roberts HC, Cooper C. Is grip strength associated with health-related quality of life? Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age and Ageing. 2006;35(4):409–415. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan OY, van Houwelingen AH, Gussekloo J, Blom JW, den Elzen WP. Comparison of quadriceps strength and handgrip strength in their association with health outcomes in older adults in primary care. Age (Dordr) 2014;36(5):9714. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9714-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visser M, Deeg DJH, Lips P, Harris TB, Bouter LM. Skeletal muscle mass and muscle strength in relation to lower-extremity performance in older men and women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(4):381–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Cavazzini C, Di Iorio A, et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: An operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;95(5):1851–1860. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiba R, Takakusaki K, Ota J, Yozu A, Haga N. Human upright posture control models based on multisensory inputs; in fast and slow dynamics. Neuroscience Research. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, Hauer K. Factors associated with fear of falling and associated activity restriction in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(1):72–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horak FB. Postural orientation and equilibrium: What do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls? Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii7–ii11. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens PJ, Syddall HE, Patel HP, Martin HJ, Cooper C, Aihie Sayer A. Is grip strength a good marker of physical performance among community-dwelling older people? The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2012;16(9):769–774. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muehlbauer T, Gollhofer A, Granacher U. Associations between measures of balance and lower-extremity muscle strength/power in healthy individuals across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N. Z.) 2015;45(12):1671–1692. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0390-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misic MM, Rosengren KS, Woods JA, Evans EM. Muscle quality, aerobic fitness and fat mass predict lower-extremity physical function in community-dwelling older adults. Gerontology. 2007;53(5):260–266. doi: 10.1159/000101826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cramm JM, van Dijk HM, Nieboer AP. The importance of neighborhood social cohesion and social capital for the well being of older adults in the community. Gerontologist. 2013;53(1):142–152. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiao C, Weng LJ, Botticello AL. Social participation reduces depressive symptoms among older adults: An 18-year longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Etman A, Kamphuis CB, van der Cammen TJ, Burdorf A, van Lenthe FJ. Do lifestyle, health and social participation mediate educational inequalities in frailty worsening? The European Journal of Public Health. 2015;25(2):345–350. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fleck MP, Chachamovich E, Trentini C. Development and validation of the Portuguese version of the WHOQOL-OLD module. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2006;40(5):785–791. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102006000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eser S, Saatli G, Eser E, Baydur H, Fidaner C. The reliability and validity of the Turkish Version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument-Older Adults Module (WHOQOL-Old) Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2010;21(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education. 2011;2:53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]