Abstract

Potassium glutamate (KGlu) is the primary Escherichia coli cytoplasmic salt. After sudden osmotic upshift, cytoplasmic KGlu concentration increases, initially because of water efflux and subsequently by K+ transport and Glu− synthesis, allowing water uptake and resumption of growth at high osmolality. In vitro, KGlu ranks with Hofmeister salts KF and K2SO4 in driving protein folding and assembly. Replacement of KCl by KGlu stabilizes protein-nucleic acid complexes. To interpret and predict KGlu effects on protein processes, preferential interactions of KGlu with 15 model compounds displaying six protein functional groups—sp3 (aliphatic) C; sp2 (aromatic, amide, carboxylate) C; amide and anionic (carboxylate) O; and amide and cationic N—were determined by osmometry or solubility assays. Analysis of these data yields interaction potentials (α-values) quantifying non-Coulombic chemical interactions of KGlu with unit area of these six groups. Interactions of KGlu with the 15 model compounds predicted from these six α-values agree well with experimental data. KGlu interactions with all carbon groups and with anionic (carboxylate) and amide oxygen are unfavorable, while KGlu interactions with cationic and amide nitrogen are favorable. These α-values, together with surface area information, provide quantitative predictions of why KGlu is an effective E. coli cytoplasmic osmolyte (because of the dominant effect of unfavorable interactions of KGlu with anionic and amide oxygens and hydrocarbon groups on the water-accessible surface of cytoplasmic biopolymers) and why KGlu is a strong stabilizer of folded proteins (because of the dominant effect of unfavorable interactions of KGlu with hydrocarbon groups and amide oxygens exposed in unfolding).

Introduction

Potassium glutamate (KGlu) is the primary low-molecular-weight cytoplasmic salt in Escherichia coli (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). The cytoplasmic concentration of K+ greatly exceeds that of Glu− and other metabolic anions because of the high concentration of nucleic acid phosphates (5, 6, 7, 8). Cytoplasmic concentrations of K+ and Glu− are highly variable depending on osmotic conditions of growth. Cytoplasmic K+ and Glu− concentrations increase after an osmotic upshift, initially because of efflux of cytoplasmic water and subsequently by osmoregulated transport of K+ and synthesis of anionic glutamate (Glu−) together with the disaccharide trehalose in the active response to this stress (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Accumulation of these solutes allows water influx and resumption of growth in a minimal (glucose) medium. If solutes like proline or glycine betaine are provided (16, 17, 18), they are preferentially accumulated in the response to osmotic stress, resulting in uptake of more water for the same mole amount of accumulated solute species, a more dilute cytoplasm, and more rapid cell growth (2, 5, 7). In vitro, the thermodynamics and kinetics of folding, assembly, and function of proteins and nucleic acids vary strongly with the concentrations of these osmolytes. KGlu, like other E. coli osmolytes, stabilizes folded proteins (19, 20). Replacement of KCl by KGlu greatly stabilizes protein-nucleic acid complexes, especially at high salt concentration (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27).

To obtain the information needed to predict or interpret in vivo and in vitro effects of E. coli osmolytes, previous research used osmometry to quantify interactions of proline, glycine betaine (GB), and trehalose with model compounds displaying the hydrocarbon and amide functional groups that are exposed in protein unfolding and with the anionic and cationic groups found on the surface of biopolymers (28, 29, 30). Solutes that interact favorably with the biopolymer surface buried in protein folding or formation of biopolymer complexes promote the exposure of this surface and are destabilizers; solutes that interact unfavorably with this biopolymer surface are stabilizers (31). Interactions of proline and GB with aliphatic hydrocarbon (sp3 C) and with amide and anionic (carboxylate, phosphate) O groups are found to be unfavorable, while interactions with aromatic (sp2) C and with cationic and amide N are favorable. Because the surface exposed in protein unfolding and the water-accessible surfaces of folded proteins and helical nucleic acids are predominantly aliphatic hydrocarbon and amide or anionic oxygen, and interactions of these groups with these solutes are predominantly unfavorable, this quantitatively explains why they are protein stabilizers and effective in vivo osmolytes (28, 29). In another approach, interactions of these osmolytes with amino acids were examined by solubility assays and interpreted in terms of interactions with the different side chains and with the peptide backbone (32). Interactions of KGlu with the functional groups of proteins have not previously been investigated.

Robinson and Von Hippel pioneered the quantitative determination of interactions of salts from the Hofmeister series, with model compounds displaying hydrocarbon and amide groups, using solubility (33, 34) and chromatography (35, 36) assays. We previously analyzed literature data quantifying the interactions of KCl, KF, and K2SO4 and other inorganic Hofmeister salts (component 3) with model compounds (component 2) displaying these groups (37). Chemical potential derivatives (d) that quantify the effect of one solute component on the chemical potential of the other (dμ2/dm3 = μ23 = μ32 = dμ3/dm2) were obtained and interpreted to determine strengths of the unfavorable or favorable interactions of these salts with a unit area of amide and hydrocarbon (C) groups. These results quantified the previous conclusion that interactions of inorganic salts with hydrocarbon groups follow the Hofmeister series of salt effects on protein processes, while interactions of these salts with amide groups do not. For example, KF is a stronger protein stabilizer than KCl because the KF-hydrocarbon interaction is significantly more unfavorable than the KCl-hydrocarbon interaction; interactions of both salts with amide (polar) groups are similarly favorable.

We used this quantitative information to interpret experimental results for the non-Coulombic effects of Hofmeister salts on protein folding and DNA helix formation (31, 38). The same order of Hofmeister salt effects is observed for both assembly processes, but the null point differs greatly. While many salts are protein stabilizers, no salt investigated is a nucleic acid stabilizer at high salt concentration where non-Coulombic effects are dominant. This key difference is readily explained in terms of 1) the different ratios of hydrocarbon (h) to polar (p) surface exposed in unfolding or melting (h/p = 2:1 for protein unfolding; h/p = 1:2 for DNA duplex melting); and 2) the opposite signs of interactions of inorganic salts with these groups (unfavorable with h, favorable with p). Semiquantitative to quantitative agreement with the experimental data was obtained (31, 38).

Here we determine preferential interactions of KGlu with a set of 15 model compounds and interpret these data to quantify interactions of KGlu with six of the seven major functional groups of proteins (sp3 (aliphatic) C and sp2 (aromatic ring, amide, carboxylate) C; amide and anionic (carboxylate) O; and amide and cationic N groups) and place KGlu in the series of Hofmeister salts. Comparison of these results with those obtained previously for interactions of inorganic salts with hydrocarbon and amide groups reveals why KGlu is a stronger protein stabilizer than any 1:1 inorganic K+ salt investigated to date, with a different balance of functional group interactions than those other salts (20). Using these data, quantitative predictions or interpretations of interactions of KGlu with native proteins and effects of KGlu on protein processes can be made in terms of information about the amount and composition of the surface area exposed or buried in these processes. Initial applications include the interpretation of experimental data quantifying the very large unfavorable interactions of KGlu and NaGlu with native proteins and the large stabilizing effect of KGlu on ribosomal protein domain NTL9.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Potassium glutamate monohydrate (>99%) was obtained from Fluka (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Methylurea, 1,1-diethlyurea, malonamide (all >97% pure), and 1,3-dimethylurea, (>99%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. 1,3-Diethylurea (>98%) was from TCI America (Portland, OR). Propionamide (>98%) was from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). Acetyl-Ala-methylamide (aama, >99%) was from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Urea, glycine, GB, and valine (>99%, valine >99.5%) were from Sigma-Aldrich, as were naphthalene and benzene (>98%). Proline (>98.5%) was from SAFC Commercial Life Science Products (part of Sigma-Aldrich). All these chemicals (except KGlu) are anhydrous. All solutes were dissolved in water purified with a Barnstead E-pure system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to no less than 18 MΩ (DI water).

Quantifying KGlu-model compound interactions by vapor pressure osmometry

Series of 5–10 three-component solutions were prepared gravimetrically in which the molal concentration of one solute was held constant (at 0.15–0.3 m for KGlu or 0.35–0.95 m for the model compound) and the concentration of the other was varied from zero to 0.6 m for KGlu and to 0.95 m for the model compound. Separate series of 10–13 two-component solutions of KGlu (0.05–0.6 m), model compound (0.05–1 m), and KCl (0.02–1.2 m) were also prepared. The osmolality of each solution was determined in at least triplicate at room temperature (23 ± 1°C) in a Wescor Model 5600 Vapor Pressure Osmometer (VPO), calibrated with Wescor standards (ELITech, Logan, UT). Bracketing KCl standards were read with each sample and used to correct its osmolality using literature isopiestic distillation data for KCl (28, 29, 39, 40).

Values of the excess osmolality ΔOsm of the KGlu-model compound solution were determined by

| (1) |

as the difference between the three-component osmolality Osm(m2,m3) and the sum of the corresponding two-component osmolalities Osm(m2,0) + Osm(0,m3). Following the usual convention, component 2 is model compound and component 3 is KGlu. For ΔOsm calculations on a series of solutions where the concentration of one solute was held constant and the other was varied, the two-component osmolality of the first solute was determined directly while that of the second was determined by interpolation of a quadratic or higher order fit of its two component osmolality as a function of its molality.

Values of the chemical potential derivative μ23 quantifying KGlu-model compound interactions were obtained from Eq. 2 as previously described in the literature (28, 29, 39, 40):

| (2) |

Values of ΔOsm were plotted as a function of the molality product m2m3 and μ23 was determined from the slope of the best-fit straight line with intercept fixed at zero. In Eq. 2, the quantity m2m3 is a measure of the probability of an interaction between the solutes, and μ23/RT is a measure of the strength of that interaction.

Measurement of the osmolality of two-component KGlu solutions as a function of KGlu molality m3 (with m2 = 0 and KGlu designated by the subscript 3 to be consistent with the notation for three-component solutions) provides analogous information about the self-interaction of KGlu. For KGlu and other 1:1 salts,

| (3a) |

where μ33 = dμ3/dm3 and the nonideality factor ε± = d lnγ±/d ln m3 where γ± is the mean ionic activity coefficient of KGlu. Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material shows the two-component osmolality of KGlu solutions is a quadratic function of KGlu molality m3 in the full concentration range investigated (0.05–1.3 molal). From the quadratic fit, dOsm/dm3 increases from 1.77 ± 0.01 at 0.05 m to 2.06 ± 0.03 at 1.3 m with a midrange value of 1.90 ± 0.03 at 0.63 m KGlu, from which ε± = −0.05 ± 0.015.

For nonelectrolyte solutes like urea, proline, and GB,

| (3b) |

and the nonideality factor ε3 = d lnγ3/d ln m3, where γ3 is the activity coefficient of the nonelectrolyte.

Quantifying KGlu-model compound interactions by solubility assays

Solubility assays at 25°C were used to determine interactions of KGlu with the aromatic hydrocarbon compounds benzene and naphthalene. Two series of 12 KGlu solutions (0–2 m) were prepared gravimetrically and an excess of naphthalene or benzene was added to each KGlu solutions as previously described in Knowles et al. (40). Effects of KGlu on the solubility of the aromatic hydrocarbon (i.e., the molal concentration in the saturated solution) were analyzed to obtain μ23 using Eq. 3, as previously described in Knowles et al. (40):

| (4) |

Values of , the extrapolated molal solubility in the absence of KGlu, were used to normalize the solubility data. For situations where component 2 (the aromatic model compound) is only sparingly soluble and component 3 (here KGlu) is in great excess, as is the case here, Eq. 4 provides an accurate determination of μ23.

Water-accessible surface area calculations

Water-accessible surface areas (ASA) of the model compounds and native proteins in Table S1, Table S2, and Table S3 were calculated from structures using the SurfRacer program (41) with the Richards set of van der Waals radii (42) and a 1.4 Å probe radius for water. For amino acids, NMR solution structures from BMRB (43, 44) were used for these calculations. Because solution structures are not available for the amides and aromatic compounds (benzene, naphthalene) investigated here, their structures were obtained from the NIH CACTUS website, as described in Guinn et al. (39). As a test for systematic differences in ASA between these sources, ASA of amino acids were also calculated using CACTUS structures. Small, nonsystematic ASA differences are observed (see Table S2); these must be considered part of the uncertainty in the parameters (α-values; Eq. 5 below) obtained from the ASA-based analysis. Contributions to the total ASA were determined for six (for amide and amino acid model compounds in Table S1) or seven (for proteins in Table S3) functional groups: sp3 C from aliphatic hydrocarbon groups, sp2 C from aromatic rings, amide C and carboxylate C; amide O, carboxyl O, and hydroxyl O (proteins only); amide N and cationic N. This analysis uses a unified atom model where hydrogens are included as part of the radius of the central atom. Structures of native proteins were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB; http://www.rcsb.org (44)). The amount and composition of the ΔASA of unfolding NTL9 was determined previously by analysis of unfolding m-values for a series of Hofmeister salts together with structural results (20).

Results

Quantifying interactions of KGlu with amides and amino acids by VPO

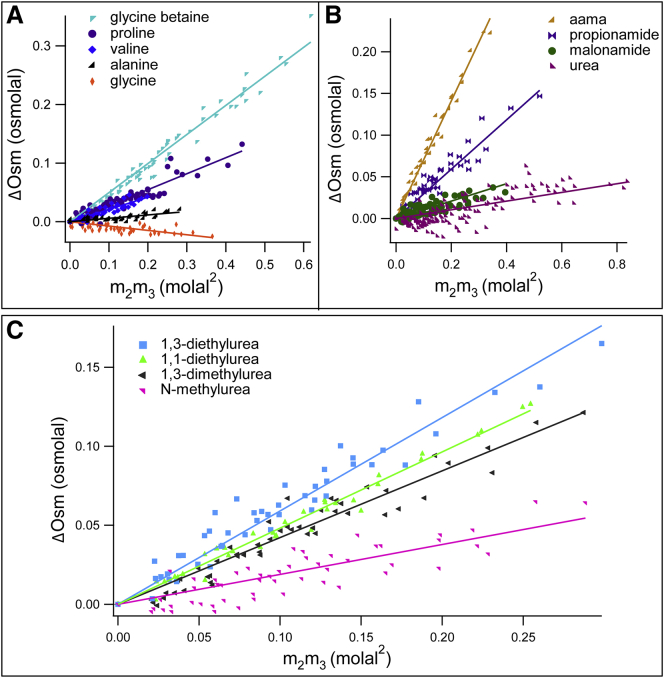

Preferential interactions of KGlu with five amino acids and with eight alkylated ureas and other amides were determined by VPO. Interactions of KGlu with proline, GB, and urea were quantified previously in the literature (28, 29, 39). These results together with additional data are reported in Fig. 1. These compounds vary widely in amount and type (sp2, sp3) of water-accessible carbon ASA (see Table S1). Urea, alkylated ureas, and other amides studied differ greatly in the amount and ratio of amide N and amide O ASA. While all amino acids have one cationic N and one carboxylate O, the N/O ratio varies widely because GB has a negligibly small cationic N ASA.

Figure 1.

Osmometric determinations of chemical potential derivatives dμ2/dm3 = μ23 quantifying preferential interactions of potassium glutamate (KGlu; component 3) with 13 model compounds displaying protein groups (component 2) at 23°C. Excess osmolalities ΔOsm (Eq. 1) are plotted against m2m3, the product of molal concentrations of the model compound and KGlu, and fitted linearly with zero intercept (see Eq. 2) to obtain μ23 from the slope. (A) Amino acids. (B) Amides (aama). (C) Alkylated ureas. For urea, GB, and proline, new and previously published results (28, 29, 39) are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Excess osmolalities (ΔOsm) of each KGlu-model compound solution (Eq. 1) are plotted versus the product of molalities of KGlu and model compound (m2m3) in Fig. 1. In all cases, ΔOsm is proportional to the m2m3 product within the experimental uncertainty, as predicted from Eq. 2 and observed previously for a wide variety of solutes (28, 29, 39, 40). The proportionality constant is μ23/RT, from which concentration-independent chemical potential derivatives μ23 quantifying preferential interactions of KGlu with these solutes are obtained at room temperature (23 ± 1°C) (see Table 1). Fig. 1 and Table 1 show that interactions of KGlu with all model compounds investigated by VPO except glycine are unfavorable. These results indicate that interactions of KGlu with one or both charged groups of glycine are favorable, while interactions of KGlu with amide and hydrocarbon groups are unfavorable.

Table 1.

Values of μ23 at 23°C for Interactions of KGlu with Model Compounds

| Model Compounda | Hydrocarbon ASA (Å2) | Experimental μ23b (cal mol−1 m−1) | Predicted μ23c (cal mol−1 m−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-ala-methylamide | 262 | 406 ± 6 | 390 ± 11 |

| 1,3-Diethylurea | 255 | 348 ± 7 | 350 ± 7 |

| Naphthalene | 275 | 322 ± 14 | 342 ± 10 |

| Glycine betaine | 197 | 292 ± 4 | 294 ± 7 |

| Benzene | 212 | 291 ± 11 | 265 ± 8 |

| 1,1-Diethylurea | 213 | 284 ± 4 | 292 ± 8 |

| 1,3-Dimethylurea | 183 | 249 ± 5 | 248 ± 6 |

| Propionamide | 129 | 174 ± 6 | 176 ± 7 |

| Proline | 151 | 161 ± 4 | 160 ± 7 |

| Valine | 148 | 117 ± 5 | 109 ± 8 |

| Methylurea | 95 | 111 ± 6 | 121 ± 8 |

| Malonamide | 57 | 48 ± 2 | 77 ± 13 |

| Alanine | 91 | 29 ± 2 | 24 ± 8 |

| Urea | 7 | 31 ± 2 | −6 ± 11 |

| Glycine | 56 | −50 ± 4 | −38 ± 8 |

Ranked from most unfavorable to most favorable experimental μ23-value.

Experimental μ23-values were obtained from VPO assays at 23°C (Fig. 1), except for benzene and naphthalene, determined from solubility assays at 25°C (Fig. S2; see Materials and Methods). Error estimates are the largest of 8% or the standard deviation determined from the linear fit of the data from Figs. 1 and S2 by Igor Pro.

Quantifying interactions of KGlu with aromatic hydrocarbons by solubility assay

Preferential interactions of KGlu with benzene and naphthalene were determined at 25°C from the effect of KGlu on the solubility of these sparingly soluble compounds. The logarithm of the solubility, normalized by the solubility in the absence of KGlu, is plotted as a function of KGlu molality m3 in Fig. S2. These plots are linear over the KGlu concentration range investigated, with slopes equal to μ23/RT from Eq. 4. Positive values of μ23/RT for the interactions of KGlu with benzene and naphthalene are obtained, indicating that these KGlu-aromatic interactions are unfavorable and that chemical potentials of the aromatics increase with increasing KGlu molality; μ23 is significantly larger for the larger aromatic hydrocarbon (naphthalene).

Trends in KGlu-model compound interactions

Table 1 ranks experimental μ23-values for KGlu-model compound interactions from most unfavorable (KGlu-aama) to least unfavorable (KGlu-alanine) and marginally favorable interactions (KGlu-glycine). Also listed are the ASA of hydrocarbon groups on each model compound from Table S1. Interactions of KGlu with all compounds investigated except glycine are unfavorable, with positive ΔOsm and μ23-values. Qualitative comparison of μ23- and hydrocarbon ASA values reveals that the model compounds that interact most unfavorably with KGlu are ones like aama, 1,3-diethylurea, and naphthalene, which have the largest amounts of hydrocarbon ASA. Values of μ23 are less unfavorable for model compounds with smaller amounts of hydrocarbon ASA. Glycine and urea compounds with small amounts of hydrocarbon ASA exhibit μ23-values that are small in magnitude.

The correlation of μ23 with hydrocarbon ASA indicates that interactions of KGlu with both sp3 C and sp2 C are unfavorable. In addition, it indicates that interactions of KGlu with the pairs of polar (amide N and O) or charged (cationic N and carboxylate O) groups on these compounds are either not very significant or make compensating contributions to μ23 so the hydrocarbon contribution is dominant. Analysis of these μ23-values shows that compensations between favorable interactions of KGlu with N (cationic, amide) and unfavorable interactions of KGlu with O (anionic, amide) are involved.

Qualitative indications of these trends are observable in comparisons of KGlu interactions with valine and proline, and with aama and 1,3-diethylurea. The largest difference in group contributions to the water ASA of the amino acid valine and the amino acid proline (see Table S1) is that valine has 25 Å2 more cationic N ASA than proline, while ASA of C and O are approximately the same. Table 1 shows that the interaction of KGlu with valine is more favorable than with proline (μ23 for KGlu-valine is significantly less positive than μ23 for KGlu-proline). Therefore the interaction of KGlu with cationic N is deduced to be favorable. Because contributions from the interactions of KGlu with cationic and anionic groups on these amino acids appear to compensate in μ23, the interaction of KGlu with carboxylate O is deduced to be unfavorable.

Likewise, the largest difference in group contributions to the ASA of aama and 1,3-diethylurea is that aama has 34 Å2 more amide O ASA than 1,3-diethylurea. (In addition, aama has 13 Å2 more amide N ASA and 7 Å2 more hydrocarbon ASA than 1,3-diethylurea.) Table 1 shows that the interaction of KGlu with 1,3-diethylurea is more favorable than with aama (μ23 for KGlu-1,3-diethylurea is significantly less positive than μ23 for KGlu-aama). Therefore, the interaction of KGlu with amide O must be unfavorable. Because contributions from the interactions of KGlu with O and N groups on these amides appear to substantially compensate in μ23, the interaction of KGlu with amide N is therefore favorable. Quantitative analysis of these μ23-values confirms these deductions.

Discussion

KGlu-model compound interactions are the sum of KGlu-group interactions

Interactions of a variety of biochemical solutes with model compounds displaying the functional groups of proteins and, in some cases, nucleic acids have been quantified in previous research, using osmometry and solubility assays. Solutes investigated include the full series of inorganic Hofmeister salts (31, 37, 38), the denaturant urea (39, 45), the osmolytes GB (28), proline (29), and trehalose (30), as well as glycerol and tetra ethylene glycol (40). Solute-model compound interactions (μ23-values) are dissected into solute-functional group interactions using Eq. 5, based on the hypothesis of additivity (tested for each data set) and ASA information for the model compounds:

| (5) |

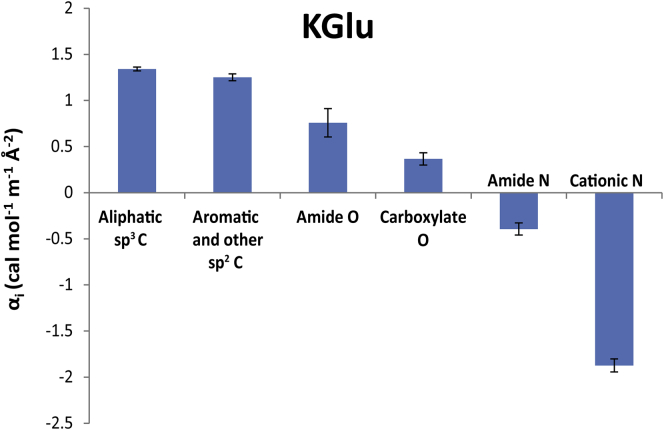

In Eq. 5, the sum is over all six functional groups present on the model compound (1 ≤ i ≤ 6), where is the water ASA (Table S1) of functional group i and αi is the intrinsic strength of interaction of KGlu with a unit area of that group (Table 2). Best-fit αi-values for strengths of interaction of KGlu with sp3 and sp2 C, amide and carboxylate O, and amide and cationic N, determined by global fitting to Eq. 5 of the 15 μ23-values from Table 1 and the ASA information from Table S1, are summarized in the bar graph of Fig. 2. These confirm the qualitative analysis of trends in the μ23-values described above.

Table 2.

KGlu-Group Interaction Potentials (αi) and Corresponding Local-Bulk KGlu Partition Coefficients (KP) at 23°C

| Surface Type, i | αi (cal mol−1 m−1 Å−2)a | SPM KPb |

|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic (sp3) C | 1.34 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.01 |

| sp2 Cc | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.01 |

| Amide O | 0.76 ± 0.15 | 0.79 ± 0.02 |

| Carboxylate O | 0.37 ± 0.07 | 0.9 ± 0.01 |

| Amide N | −0.39 ± 0.07 | 1.11 ± 0.01 |

| Cationic N | −1.87 ± 0.07 | 1.52 ± 0.01 |

αi is defined in Eq. 5. Propagated uncertainties of αi-values are calculated from the ASA matrix and experimental uncertainties matrix (40).

Kp calculated from Eq. 6 using a lower-bound hydration b1 = 0.18 H2O/Å2 (37) and a midrange value of dOsm/dm3 = 2 (1 + ε±) = 1.90 ± 0.03 for KGlu self-interactions (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S1).

sp2 C includes aromatic C, amide C, and carboxylate C (see Table S1).

Figure 2.

Interaction potentials (α-values) quantifying interactions of KGlu with a unit area of each functional group of model compound at 23–25°C. Unfavorable interactions have positive α-values. To see this figure in color, go online.

A positive α-value indicates an unfavorable interaction of KGlu with that group while a negative α-value indicates a favorable interaction. Fig. 2 shows that interactions of KGlu with sp3 C, sp2 C, and with amide and carboxylate O are unfavorable (in this order), while interactions of KGlu with amide and cationic N are favorable. The unfavorable α-value for interaction of KGlu with amide O is twice as large in magnitude and opposite in sign to the favorable α-value for interaction of KGlu with amide N.

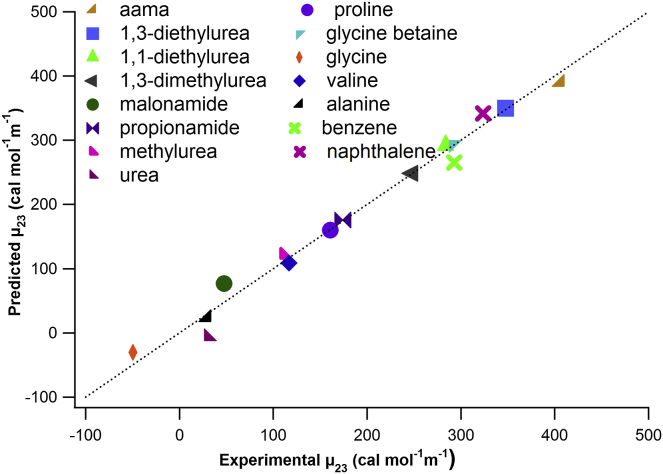

Fig. 3 compares experimentally observed μ23-values for interactions of KGlu with these 15 model compounds with those predicted from Eq. 4 and the best-fit αi-values from Table 2. A numerical comparison is provided in Table 1. For most of the data set, predicted and observed μ23-values agree within the combined uncertainties of these values. Exceptions are urea and malonamide. The disagreement for urea is surprising because αi-values quantifying the interactions of urea with the functional groups of Glu− and with K+ successfully predict the urea (solute)—KGlu (model compound) interactions (μ23 = μ32: the predicted μ23-value for the urea-KGlu interaction from those urea αi-values is 45 ± 18 cal mol−1 m−1 (39)). Interactions of KGlu with other amides and with amino acids and derivatives in Table 1 are well predicted from these αi-values, validating the assumption of additivity (Eq. 5).

Figure 3.

Predicted versus experimental (observed) values of μ23 for interactions of KGlu with model compounds at 23°C (see Table 1). (Line) Equality of predicted and observed values. To see this figure in color, go online.

The ASA of backbone amide groups of proteins is ∼70% amide O, 25% amide N, and 5% amide C, while side-chain amide ASA is ∼35% amide O, 60% amide N, and 5% amide C. From Table 1, the composite αi-value for the interaction of KGlu with backbone amide groups is predicted to be moderately unfavorable (0.50 cal mol−1 m−1 Å−2) while the interaction of KGlu with side-chain amide groups is predicted to be only slightly unfavorable (0.11 cal mol−1 m−1 Å−2). The number of backbone amide groups greatly outnumbers the number of side-chain amide groups in most proteins, so the overall interaction of KGlu with amide ASA of proteins is predicted to be moderately unfavorable. Interactions of KGlu with all C groups (both sp3 C and sp2 C) are very unfavorable, with α-values that exceed those for KGlu-amide O and KGlu-carboxylate O interactions. Because typically >85% of the ASA exposed in unfolding a globular protein is hydrocarbon and amide, the unfavorable interactions of KGlu with these groups explain why KGlu stabilizes folded proteins. Quantitative interpretation of the KGlu m-value for unfolding NTL9 confirms this conclusion (20).

Interpretation of KGlu α-values as net effects of local accumulation or exclusion of K+ and Glu− ions

Because KGlu is a strong electrolyte, completely dissociated into ions in solution, these component μ23-values and α-values must be interpreted as the net thermodynamic effect of the interaction of K+ and Glu− ions with the compound or functional group (31, 37). This interpretation is most readily made at the level of ion partition coefficients Kp that quantify the accumulation or exclusion of K+ and Glu− in the vicinity of each compound or group.

KGlu α-values are interpreted in terms of the local distributions of K+ and Glu− ions in the vicinity of protein functional groups using a molecular thermodynamic analysis of the solute partitioning model (SPM) (31, 37, 46, 47, 48, 49). Negative (positive) α-values, indicating net favorable (unfavorable) KGlu-group interactions, correspond to net accumulation (exclusion) of K+ and Glu− ions in the vicinity of the group, relative to the bulk KGlu concentration. The SPM approximates the continuous radial distribution of an uncharged solute or salt ion in the vicinity of a surface or group by an average local concentration (m3,local) that in general differs from the bulk solute concentration (m3,bulk). Interpreted using the SPM, the experimental finding that μ23-values and α-values are independent of m3,bulk means that m3,local is proportional to m3,bulk. The proportionality constant in this relationship is a concentration-independent local-bulk partition coefficient Kp (Kp = m3,local/m3,bulk), which is the microscopic analog of a partition coefficient or observed equilibrium constant for partitioning of a solute between two macroscopic phases.

For a salt like KGlu with ν-ions per formula unit (ν = ν+ + ν−), each KGlu-group interaction potential αi is related to the corresponding local-bulk partition coefficient Kp,i of the electro-neutral salt by the SPM result (Eq. 6):

| (6) |

where b1,i is the surface density of water in the hydration layer of functional group i. Lower bounds on b1,i for different groups are ∼0.18 H2O/Å2 or two layers of local water of hydration, obtained from studies with highly excluded solutes (28, 31, 37). The term ε± = d ln γ±/d ln m3 in Eq. 6 accounts for KGlu self-interaction (see Eq. 3 a).

For a 1:1 salt like KGlu, these salt Kp values are interpreted as the arithmetic averages of the Kp values for the cation and anion (37):

| (7) |

The SPM derivation predicts that individual ion contributions should be quantified by single-ion Kp values and not by defining single ion α-values (31, 48, 49).

For the electroneutral KGlu component, Kp values quantifying the net accumulation or exclusion of its ions in the vicinity of the protein functional groups investigated are listed in Table 2. For the intrinsically most unfavorable interactions of KGlu with aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbon groups, the tabulated Kp values indicate that the average of the local concentrations of K+ and Glu− ions near hydrocarbon groups is only two-thirds of the overall (bulk) KGlu concentration (local exclusion). At the other extreme of the most favorable interaction of KGlu with cationic N, the tabulated Kp value indicates that the average of the local concentrations of K+ and Glu− ions near cationic N group is ∼50% larger than the overall (bulk) KGlu concentration (local accumulation). Table 2 also shows that the ions of KGlu are more excluded from amide O than from carboxylate O, and less accumulated at amide N than at cationic N.

Even in the relatively high salt, non-Coulombic regime investigated here, K+ is expected to interact unfavorably with (i.e., be locally excluded from; Kp,+ < 1) hydrocarbon C and amide N, and to interact favorably with (i.e., be locally accumulated near; Kp,+ > 1) amide O. Likewise K+ is expected to interact favorably with carboxylate O but unfavorably with cationic N. Based on these expectations, interactions of Glu− with cationic and amide N must be quite favorable (Kp,− ≫ 1) and interactions of Glu− with anionic and amide O must be quite unfavorable (Kp,− ≪ 1) to yield the observed KGlu component α-values in Table 2. Experiments are in progress to determine single-ion Kp values and test these predictions, as well as to further dissect interactions of Glu− with protein functional groups into interactions of individual groups on Glu− with those protein groups.

Prediction and interpretation of the massive unfavorable interactions of glutamate salts with folded proteins: relevance for the effectiveness of KGlu as an E. coli osmolyte

Arakawa and Timasheff (19) determined preferential interactions (μ23) of NaGlu with tubulin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), β-lactoglobulin, and lysozyme by dialysis and densimetry (20°C, pH 7 Table 3). Courtenay et al. (50) determined the preferential interaction of KGlu with BSA by VPO (24–25°C, near neutral pH). Interactions of KGlu and NaGlu with these proteins, ranging in size from 14.3 kDa (lysozyme) to 96.7 kDa (tubulin dimer) and from negatively to positively charged at pH 7, are highly unfavorable. A 1 molal increase in NaGlu concentration increases the chemical potential of lysozyme by ∼6 kcal/mol and increases the chemical potential of tubulin dimer by 28 kcal/mol. To a first approximation, values of μ23 for these glutamate salt-protein interactions increase in proportion to the water accessible surface area, as well as to molecular weight and molecular volume of the protein. For example, Table 3 shows that experimental values of are in the range 0.8–1.3 cal mol−1 molal−1 Å−2.

Table 3.

Comparison of Observed and Predicted Interactions of KGlu or NaGlu with Globular Proteins and KGlu m-values for NTL9 Unfolding

| Proteina (Preferential Interaction) | Salt (Concentration) |

μ23 (kcal mol−1 m−1) |

μ23/ASA (cal mol−1 m−1Å−2)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Predictedc | Observed | Predictedc | ||

| Tubulin | NaGlu(1 M) | 27.6 ± 3.7d | 18.6 ± 4 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| BSA | KGlu (0–1 molal) | 22.4 ± 2.2e | 18 ± 2.7 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| NaGlu (1 M) | 35.9 ± 2.3d | 18 ± 2.7 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | |

| β-lactoglobulin | NaGlu (1 M) | 18.9 ± 0.6d | 9.3 ± 1.8 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Lysozyme | NaGlu (1 M) | 5.7 ± 2.5d | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| Protein unfolding | salt (concentration) | m-value = Δμ23 (kcal mol−1 m−1) | m-value/ΔASA = Δμ23/ΔASA (cal mol−1 m−1 Å−2) | ||

| Observed | Predicted | Observed | Predicted | ||

| NTL9f | KGlu (0–1.5 M) | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

Tubulin and β-lactoglobulin are dimers; BSA and lysozyme are monomers.

PDB files used for ASA calculations (see Table S3) are PDB: 1TUB for tubulin (59); PDB: 4F5S for BSA (60); PDB: 4TLJ for β-lactoglobulin (61); and PDB: 6LYZ for lysozyme (62).

Predicted μ23-values are calculated from Eq. 5 using αi-values from Table 1 and ASA information from Table S3.

Values of μ23 for interactions of NaGlu with native proteins at 20°C are calculated from the Donnan coefficient Γ23 ≈ −μ23/μ33 (obtained by dialysis/densimetry (19)) using = 1.90 RT/m3 determined for KGlu in Fig. S1.

Value of μ23 for interaction of KGlu with BSA is calculated from Γ23 determined by VPO at 24–25°C (29) using = 1.90 RT/m3.

Experimental NTL9 m-value is from Sengupta et al. (20), with an estimated experimental uncertainty of ±10%. Predicted NTL9 m-value and uncertainty are calculated from Eq. 8 using the six αi-values from Table 1 and estimates of the corresponding ΔASAi for unfolding NTL9 to the best-fit (compact) model of the denatured state ensemble at 20°C (20).

Are these massive effects of KGlu or NaGlu on protein chemical potentials predominantly excluded volume (physical) effects, or do they arise from unfavorable chemical interactions of KGlu or NaGlu with functional groups on the protein surface? To answer this question, we predict the chemical interactions of KGlu with the functional groups on the surface of these proteins using the composition of the ASA (Table S3) and the α-values from Table 2 using Eq. 5. These predictions of μ23, listed in Table 3, agree with experimental values within the combined uncertainty for three of the five cases (KGlu-BSA, NaGlu-tubulin, NaGlu-lysozyme), and are ∼50% too small for the other two cases (NaGlu-BSA, NaGlu-β-lactoglobulin). The two discrepancies may not be a failure of the predictions; Table 3 indicates that the predicted values of for NaGlu-BSA and NaGlu-β-lactoglobulin interactions, not the experimental , are consistent with predicted and experimental values of for KGlu-BSA, NaGlu-tubulin, and NaGlu-lysozyme.

These predictions do not take account of the interaction of KGlu with hydroxyl O because this α-value has not been determined. This interaction is expected to be unfavorable and much smaller in magnitude than α-values for interactions of KGlu with amide and carboxylate O. Because hydroxyl O ASA is only a small fraction of the total ASA or ΔASA of the proteins and process considered, we expect its contribution will be negligible. We assume that contributions of Na+ and K+ to these α-values are similar, as has been seen in previous comparisons (37, 38). Finally, we neglect the contribution to the predicted μ23 from what is expected to be a modest favorable interaction of KGlu or NaGlu with the inorganic counterions (Na+ or Cl−) of the electroneutral protein component. For other solutes, these interactions can be unfavorable and make a more significant contribution, as for the interaction of PEG with the Cl- counterions of lysozyme (51).

At a molecular level, we conclude that chemical exclusion of KGlu or NaGlu from the water of hydration of hydrocarbon and carboxylate and amide oxygen groups of these proteins is sufficient to explain the origin of the large unfavorable thermodynamic effect (increase in protein chemical potential) upon addition of KGlu or NaGlu, and that physical (excluded volume) effects are not the origin of this effect. Theoretical and experimental results with other solutes provide support for this conclusion. Both scaled particle theory (52, 53) and theory of two-component hard-sphere fluid mixtures (54) indicate that excluded volume effects become negligible when the size of the solute becomes comparable to that of the solvent. Preferential interactions of small oligoethylene glycols (ethylene glycol to tetraethylene glycol or PEG200) with proteins and effects of these small oligoethylene glycols on protein and nucleic acid processes are quantitatively interpreted as chemical interactions using model compound data. Only for larger PEGs do physical excluded volume effects contribute (40, 51). While PEG200 and the hydrated ions of KGlu are larger than a single water molecule, these solutes are comparable in size to that of a hydrogen-bonded cluster of water molecules in liquid water.

In solutions of proteins and glutamate salts, key functional groups on these proteins and on the glutamate salts prefer to interact with water than with each other, resulting in net chemical exclusion of the ions of KGlu and NaGlu from the water of hydration of the protein and a smaller average local ion concentration than the bulk salt concentration. This local exclusion causes the chemical potential of a protein to increase linearly with KGlu or NaGlu molal concentration, with slope μ23. For the series of proteins investigated, μ23 increases with increasing protein surface area (ASA), as summarized in Table 3.

Prediction and interpretation of effects of KGlu on protein folding

The often-large effects of stabilizing and destabilizing solutes and the non-Coulombic effects of Hofmeister salts like KGlu on biopolymer processes are manifested as a linear dependence of the observed standard free energy change (ΔGoobs = −RT ln Kobs) on solute concentration (20, 38). The slope of this plot, typically called the m-value, is equal to the difference in μ23-values between products and reactants (Δμ23 = dΔGoobs/dm3 = m-value). Because the underlying solute-biopolymer interactions are short range, Δμ23 is accurately interpreted as the interactions of the solute with the biopolymer surface that is exposed or buried in the process (i.e., the ΔASA). Because μ23 = (Eq. 5), therefore

| (8) |

Addition of KGlu strongly stabilizes ribosomal protein NTL9 (the 56-residue N-terminal domain of ribosomal protein L9) against unfolding, with an observed m-value of 1.9 ± 0.2 kcal mol−1 m−1 at 20°C. Unfolding of NTL9 exposes primarily hydrocarbon and amide groups; approximately two-thirds of the ΔASA is hydrocarbon and one-quarter is amide, accounting for >90% of the ΔASA. Table 2 shows that KGlu interacts unfavorably with all hydrocarbon groups and with oxygens, but interacts favorably with nitrogens. For the ∼1.1: 1 ratio of amide O: amide N ASA exposed in unfolding NTL9 (20), the KGlu-amide interaction is unfavorable, with a net KGlu-amide α-value = 0.2 ± 0.1 cal mol−1 m−1 Å−2 from Table 2. For the ∼7.7:1 ratio of aliphatic to aromatic C exposed in unfolding NTL9, the net KGlu-hydrocarbon α-value is 1.33 ± 0.03 cal mol−1 m−1 Å−2 from Table 2.

We (20) used published α-values for interactions of inorganic Hofmeister salts with hydrocarbon and amide groups to predict m-values for unfolding NTL9 in destabilizing and stabilizing salts from ASA information using Eq. 8. From a comparison of predicted and observed ΔASA of unfolding, we concluded that substantial structure remains in the unfolded form of NTL9. We predicted that the ΔASA of unfolding (1577 Å2) is only one-third of that predicted for unfolding to a completely unstructured unfolded form (4340 Å2). Using this ΔASA of unfolding NTL9 (see Table S3), we predict an unfolding m-value of 1.4 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1 m−1 at 23 ± 1°C. Predicted and observed m-values agree at the limits of their combined uncertainties (Table 3). By far the major contribution to the m-value is predicted to be from exposing hydrocarbon groups (m-value contribution of 1.47 cal mol−1 m−1) with minor offsetting contributions from exposing amide groups (0.1 cal mol−1 m−1) and charged groups (−0.13 cal mol−1 m−1). We are determining interactions of KCl and other Hofmeister salts with amino acids and their derivatives, amides, alkylated ureas, aromatics, nucleobases, and other model compounds to test the previously determined hydrocarbon and amide α-values, dissect amide α-values into O and N interactions, and determine interactions of Hofmeister salts with charged groups. These results will not only improve the analysis of salt effects on protein folding but also will provide the quantitative information needed to interpret the large stabilizing effects of replacing KCl with KGlu on protein-nucleic acid interactions.

Comparison of interactions of KGlu and other Hofmeister salts with hydrocarbon and amide groups

KGlu interacts unfavorably with carbon (sp3 (aliphatic) C, sp2 (aromatic, amide, carboxylate) C) and oxygen (amide O and carboxylate O) groups, and interacts favorably with nitrogen groups (amide N and cationic N). Because the α-value (Table 2) quantifying the unfavorable interaction of KGlu with unit area of amide O is twice as large in magnitude as that for interaction of KGlu with unit area of amide N, KGlu is predicted to interact very unfavorably with backbone (2°) amide groups (large O/N; e.g., 2.8 for aama (Table S1)) and slightly unfavorably with side-chain (1°) amide groups (small O/N; e.g., 0.6 for propionamide (Table S1). This net-unfavorable interaction of KGlu with amide groups differs greatly from the net-favorable interactions of inorganic Hofmeister salts with amide groups (often characterized as salting-in of amides (33, 34, 37)). For inorganic salts, the classical Hofmeister series ranking for protein processes is determined by the rank order of interactions of these salts with hydrocarbon groups; interactions with amide groups are largely favorable and do not follow the Hofmeister series order. On the basis of its interaction with hydrocarbon groups, KGlu would be ranked between KCl and KF as a moderate stabilizer, but its net-unfavorable interaction with amide groups significantly increases its effectiveness as a protein stabilizer, so that KGlu ranks between KF and K2SO4 and is almost as effective on a per-ion basis as K2SO4. Hence the explanation for the Hofmeister ranking of KGlu is analogous to that previously determined for GuHCl, which on the basis of its interaction with hydrocarbon groups would not be a strong protein destabilizer. GuHCl is a strong destabilizer primarily because of its very favorable interaction with amide groups (37, 55).

Comparison of KGlu α-values and KGlu-protein μ23-values with those of other E. coli osmolytes and urea

When osmotically stressed during growth in a minimal glucose-salt medium, E. coli increases cytoplasmic amounts of KGlu and trehalose by transport of K+ and synthesis of Glu− and trehalose to maintain growth up to an external osmolality of ∼1.8 Osm (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). If proline or GB is present at low concentration in the growth medium, these solutes are accumulated instead of KGlu and trehalose, increasing growth rate and significantly extending the range of external osmolalities of growth (2, 7, 14). Hence proline and GB are often called osmoprotectants. All these osmolytes increase the stability of globular proteins (19, 56). Proline reduces the stability of nucleic acid duplexes and various tertiary structures (57). GB also reduces the stability of nucleic acid duplexes (57, 58) but increases the stability of various RNA tertiary structures (57), a result that is explained by the highly unfavorable interaction of GB with RNA phosphate oxygens (28) that are buried in forming these tertiary structures.

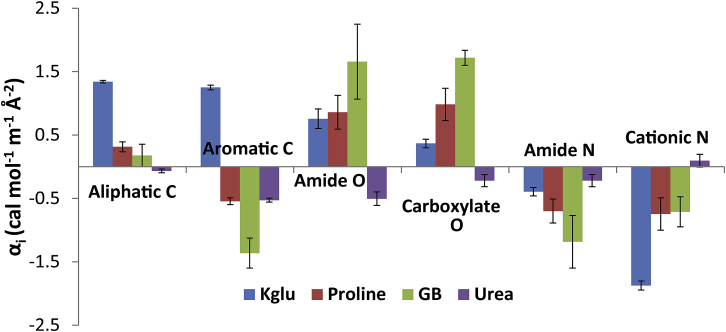

Fig. 4 compares α-values for the interactions of osmolytes/stabilizers KGlu, proline, and GB and the destabilizer urea with protein functional groups. A clear contrast is evident between all three osmolytes/stabilizers and urea. All three osmolytes interact unfavorably with aliphatic C and with amide and anionic (carboxylate) O, while urea interacts favorably with these groups. In the concentrated biopolymer environment of the cytoplasm, unfavorable interactions of KGlu, proline, and GB with anionic (carboxylate, phosphate) O, aliphatic C, and amide O groups on the surface of proteins, nucleic acids, and the cytoplasmic membrane increase the osmolality of the cytoplasm above the ideal value based solely on the molal concentration of these solutes. The unfavorable interactions make these solutes more effective osmolytes in vivo than solutes like urea that would interact favorably with these biopolymer groups and hence reduce cytoplasmic osmolality from its ideal value. Experimental evidence for this from direct measurements of solute-protein and solute-nucleic acid interactions has been presented previously for GB and proline (28, 29); additional evidence from analysis of interactions of these solutes and KGlu with BSA is discussed in the next section.

Figure 4.

Comparison of α-values for interactions of cytoplasmic osmolytes (KGlu, proline (29), and GB (28)) and urea (39) with protein functional groups at 23°C. To see this figure in color, go online.

The rank order of effectiveness of these solutes as osmolytes in the cytoplasm of E. coli is GB ≫ proline > KGlu (2, 5, 7). This order of in vivo effectiveness is the same as the order of interaction of these solutes with the anionic protein BSA (as quantified by μ23-values; Table S4). Fig. 4 reveals that the order of in vivo effectiveness is also the same as the order of interaction of these solutes with anionic and amide O (GB most unfavorable; KGlu least unfavorable), but is opposite to their order of interaction with aliphatic and aromatic C (KGlu most unfavorable; GB least unfavorable/most favorable). Interactions of all these osmolytes with cationic and amide N are favorable. Additionally, Fig. S1 and Table S4 reveal that the rank order of in vivo effectiveness is the same as the order of self-interactions of these solutes (see Eq. 3): the GB self-interaction is highly unfavorable (from dOsm/dm3, m3μ33ex/RT = ε3(GB) = 0.14), the proline self-interaction is modestly unfavorable (m3μ33ex/RT = ε3(Proline) = 0.04), while the KGlu self-interaction is favorable (m3μ33ex/RT = ε±(KGlu) = −0.05). This probably is also the order of their interaction with cytoplasmic metabolites, most of which are carboxylate or phosphate salts. These results may provide insight into the types of biopolymer surface that are water accessible in biopolymer assemblies in the cytoplasm. Biopolymer assembly is often driven by the hydrophobic effect, burying hydrocarbon groups. The water-accessible surface of these assemblies in vivo appears to be enriched in anionic (protein carboxylate, nucleic acid phosphate) and amide oxygens, with limited exposure of amide and cationic nitrogen groups.

Unfavorable self-interactions and unfavorable interactions with other solutes and biopolymers increase the effectiveness of a cytoplasmic solute in retaining cytoplasmic water and resisting dehydration in vivo. E. coli accumulates similar mole amounts of the different osmolytes in response to a given osmotic stress (2); the greater effectiveness of GB as compared to proline or the ions of KGlu allows the cytoplasm to retain more water at high osmolality using GB rather than proline or KGlu (2). The more dilute cytoplasm at high osmolality with GB as the osmolyte results in a much faster growth rate, for reasons that are only incompletely understood (5).

Although KGlu has not generally been considered as an osmoprotectant, the results of this study show that it is very analogous to osmoprotectants GB and proline in its net-unfavorable interactions with protein functional groups. Hence KGlu should be considered an osmoprotectant, though less effective in vivo than GB and proline because their self-interactions are unfavorable and their interactions with the functional groups of native proteins are on balance more unfavorable than those (per-ion) of KGlu.

Interactions of the E. coli osmolyte and protein stabilizer trehalose with protein functional groups have been studied at 0°C by freezing point depression osmometry (30). The pattern of interactions is very different from the other osmolytes at 23°C presented in Fig. 4. Interactions of trehalose with amide and anionic (carboxylate) O are favorable at 0°C, while interactions with sp2 and especially sp3 C are sufficiently unfavorable to make trehalose a protein stabilizer. It will be important to investigate interactions of trehalose with protein groups at 20–25°C to compare with the other osmolytes in Fig. 4.

To be an effective intracellular osmolyte, providing the maximum osmolality at a given concentration of the osmolyte, a solute must interact unfavorably with the native biopolymers (protein, nucleic acid, membrane) and small solutes of the cell. The ASA of these biopolymers and solutes is largely aliphatic hydrocarbon and anionic (carboxylate, phosphate) and amide oxygen, so it is not a surprise that all E. coli osmolytes investigated to date have unfavorable interactions with these hydrocarbon and oxygen groups. Urea would not be nearly as effective an osmolyte because it interacts favorably with these groups. To be an effective protein stabilizer, a solute must interact unfavorably with the protein ASA that is exposed in unfolding. This ΔASA of unfolding is primarily aliphatic hydrocarbon and amide oxygen, with smaller amounts of aromatic hydrocarbon, amide nitrogen, and charged or other polar groups. Unfavorable interactions of E. coli osmolytes with amide oxygen and aliphatic hydrocarbon groups make these osmolytes effective protein stabilizers, while favorable interactions of urea with these groups make urea a protein destabilizer.

Author Contributions

X.C., E.J.G., and M.T.R. designed the research; E.B., R.W., X.C., and E.J.G. performed the experiments; X.C., R.S., I.A.S., and M.T.R. analyzed the data; and X.C. and M.T.R. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yingxi Mao for writing custom MATLAB code for evaluating propagated uncertainty for Tables 1 and 2.

Support from National Institutes of Health grant No. GM047022 (to M.T.R.) and the University of Wisconsin-Madison is gratefully acknowledged.

Editor: Timothy Lohman.

Footnotes

Emily J. Guinn’s present address is Institute for Quantitative Biosciences, UC-Berkeley, Berkeley, California.

Evan Buechel’s present address is Department of Genetics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

Rachel Wong’s present address is Department of Immunology, Washington University Medical School, St. Louis, Missouri.

Two figures and four tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30823-2.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Richey B., Cayley D.S., Record M.T., Jr. Variability of the intracellular ionic environment of Escherichia coli. Differences between in vitro and in vivo effects of ion concentrations on protein-DNA interactions and gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:7157–7164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cayley S., Lewis B.A., Record M.T., Jr. Origins of the osmoprotective properties of betaine and proline in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:1586–1595. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1586-1595.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cayley S., Record M.T., Jr., Lewis B.A. Accumulation of 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonate by osmotically stressed Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:3597–3602. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3597-3602.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinnbier U., Limpinsel E., Bakker E.P. Transient accumulation of potassium glutamate and its replacement by trehalose during adaptation of growing cells of Escherichia coli K-12 to elevated sodium chloride concentrations. Arch. Microbiol. 1988;150:348–357. doi: 10.1007/BF00408306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cayley S., Record M.T., Jr. Roles of cytoplasmic osmolytes, water, and crowding in the response of Escherichia coli to osmotic stress: biophysical basis of osmoprotection by glycine betaine. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12596–12609. doi: 10.1021/bi0347297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cayley S., Lewis B.A., Record M.T., Jr. Characterization of the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli K-12 as a function of external osmolarity. Implications for protein-DNA interactions in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;222:281–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90212-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Record M.T., Jr., Courtenay E.S., Guttman H.J. Responses of E. coli to osmotic stress: large changes in amounts of cytoplasmic solutes and water. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Record M.T., Jr., Courtenay E.S., Guttman H.J. Biophysical compensation mechanisms buffering E. coli protein-nucleic acid interactions against changing environments. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein W., Schultz S.G. Cation transport in Escherichia coli: V. Regulation of cation content. J. Gen. Physiol. 1965;49:221–234. doi: 10.1085/jgp.49.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakajima H., Yamato I., Anraku Y. Quantitative analysis of potassium ion pool in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Biochem. 1979;85:303–310. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn A., Kellenberger E. Productive phage infection in Escherichia coli with reduced internal levels of the major cations. J. Bacteriol. 1985;163:906–912. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.906-912.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Measures J.C. Role of amino acids in osmoregulation of non-halophilic bacteria. Nature. 1975;257:398–400. doi: 10.1038/257398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen P.I., Sydnes L.K., Strøm A.R. Osmoregulation in Escherichia coli by accumulation of organic osmolytes: betaines, glutamic acid, and trehalose. Arch. Microbiol. 1987;147:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00492896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tempest D.W., Meers J.L., Brown C.M. Influence of environment on the content and composition of microbial free amino acid pools. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1970;64:171–185. doi: 10.1099/00221287-64-2-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munro G.F., Hercules K., Sauerbier W. Dependence of the putrescine content of Escherichia coli on the osmotic strength of the medium. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:1272–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csonka L.N. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol. Rev. 1989;53:121–147. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.121-147.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood J.M. Osmosensing by bacteria: signals and membrane-based sensors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:230–262. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.230-262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood J.M., Bremer E., Smith L.T. Osmosensing and osmoregulatory compatible solute accumulation by bacteria. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001;130:437–460. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arakawa T., Timasheff S.N. The mechanism of action of Na glutamate, lysine HCl, and piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) in the stabilization of tubulin and microtubule formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:4979–4986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sengupta R., Pantel A., Record M.T., Jr. Positioning the intracellular salt potassium glutamate in the Hofmeister series by chemical unfolding studies of NTL9. Biochemistry. 2016;55:2251–2259. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leirmo S., Harrison C., Record M.T., Jr. Replacement of potassium chloride by potassium glutamate dramatically enhances protein-DNA interactions in vitro. Biochemistry. 1987;26:2095–2101. doi: 10.1021/bi00382a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohman T.M., Chao K., Runyon G.T. Large-scale purification and characterization of the Escherichia coli rep gene product. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:10139–10147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deredge D.J., Baker J.T., Licata V.J. The glutamate effect on DNA binding by pol I DNA polymerases: osmotic stress and the effective reversal of salt linkage. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;401:223–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha J.H., Capp M.W., Record M.T., Jr. Thermodynamic stoichiometries of participation of water, cations and anions in specific and non-specific binding of lac repressor to DNA. Possible thermodynamic origins of the “glutamate effect” on protein-DNA interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;228:252–264. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90504-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menetski J.P., Varghese A., Kowalczykowski S.C. The physical and enzymatic properties of Escherichia coli recA protein display anion-specific inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10400–10404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontur W.S., Capp M.W., Record M.T., Jr. Probing DNA binding, DNA opening, and assembly of a downstream clamp/jaw in Escherichia coli RNA polymerase-lambdaP(R) promoter complexes using salt and the physiological anion glutamate. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4361–4373. doi: 10.1021/bi100092a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overman L.B., Bujalowski W., Lohman T.M. Equilibrium binding of Escherichia coli single-strand binding protein to single-stranded nucleic acids in the (SSB)65 binding mode. Cation and anion effects and polynucleotide specificity. Biochemistry. 1988;27:456–471. doi: 10.1021/bi00401a067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capp M.W., Pegram L.M., Record M.T., Jr. Interactions of the osmolyte glycine betaine with molecular surfaces in water: thermodynamics, structural interpretation, and prediction of m-values. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10372–10379. doi: 10.1021/bi901273r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diehl R.C., Guinn E.J., Record M.T., Jr. Quantifying additive interactions of the osmolyte proline with individual functional groups of proteins: comparisons with urea and glycine betaine, interpretation of m-values. Biochemistry. 2013;52:5997–6010. doi: 10.1021/bi400683y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong J., Gierasch L.M., Liu Z. Its preferential interactions with biopolymers account for diverse observed effects of trehalose. Biophys. J. 2015;109:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Record M.T., Jr., Guinn E., Capp M. Introductory lecture: interpreting and predicting Hofmeister salt ion and solute effects on biopolymer and model processes using the solute partitioning model. Faraday Discuss. 2013;160:9–44. doi: 10.1039/c2fd20128c. discussion 103–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auton M., Rösgen J., Bolen D.W. Osmolyte effects on protein stability and solubility: a balancing act between backbone and side-chains. Biophys. Chem. 2011;159:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nandi P.K., Robinson D.R. The effects of salts on the free energies of nonpolar groups in model peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:1308–1315. doi: 10.1021/ja00759a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nandi P.K., Robinson D.R. The effects of salts on the free energy of the peptide group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:1299–1308. doi: 10.1021/ja00759a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Hippel P.H., Hamabata A. Model studies on the effects of neutral salts on the conformational stability of biological macromolecules. J. Mechanochem. Cell Motil. 1973;2:127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamabata A., von Hippel P. Model studies on effects of neutral salts on conformational stability of biological macromolecules. 2. Effects of vicinal hydrophobic groups on specificity of binding of ions to amide groups. Biochemistry. 1973;12:1264–1271. doi: 10.1021/bi00731a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pegram L.M., Record M.T., Jr. Thermodynamic origin of Hofmeister ion effects. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9428–9436. doi: 10.1021/jp800816a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pegram L.M., Wendorff T., Record M.T., Jr. Why Hofmeister effects of many salts favor protein folding but not DNA helix formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7716–7721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913376107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guinn E.J., Pegram L.M., Record M.T., Jr. Quantifying why urea is a protein denaturant, whereas glycine betaine is a protein stabilizer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16932–16937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109372108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knowles D.B., Shkel I.A., Record M.T. Chemical interactions of polyethylene glycols (PEGs) and glycerol with protein functional groups: applications to effects of PEG and glycerol on protein processes. Biochemistry. 2015;54:3528–3542. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsodikov O.V., Record M.T., Jr., Sergeev Y.V. Novel computer program for fast exact calculation of accessible and molecular surface areas and average surface curvature. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:600–609. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livingstone J.R., Spolar R.S., Record M.T., Jr. Contribution to the thermodynamics of protein folding from the reduction in water-accessible nonpolar surface area. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4237–4244. doi: 10.1021/bi00231a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulrich E.L., Akutsu H., Markley J.L. BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D402–D408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Bourne P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guinn E.J., Schwinefus J.J., Record M.T., Jr. Quantifying functional group interactions that determine urea effects on nucleic acid helix formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5828–5838. doi: 10.1021/ja400965n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Courtenay E.S., Capp M.W., Record M.T., Jr. Thermodynamic analysis of interactions between denaturants and protein surface exposed on unfolding: interpretation of urea and guanidinium chloride m-values and their correlation with changes in accessible surface area (ASA) using preferential interaction coefficients and the local-bulk domain model. Proteins. 2000;4(Suppl 4):72–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(2000)41:4+<72::aid-prot70>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felitsky D.J., Record M.T., Jr. Application of the local-bulk partitioning and competitive binding models to interpret preferential interactions of glycine betaine and urea with protein surface. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9276–9288. doi: 10.1021/bi049862t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pegram L.M., Record M.T., Jr. Partitioning of atmospherically relevant ions between bulk water and the water/vapor interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14278–14281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606256103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pegram L.M., Record M.T., Jr. Hofmeister salt effects on surface tension arise from partitioning of anions and cations between bulk water and the air-water interface. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:5411–5417. doi: 10.1021/jp070245z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Courtenay E.S., Capp M.W., Record M.T., Jr. Vapor pressure osmometry studies of osmolyte-protein interactions: implications for the action of osmoprotectants in vivo and for the interpretation of “osmotic stress” experiments in vitro. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4455–4471. doi: 10.1021/bi992887l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shkel I.A., Knowles D.B., Record M.T., Jr. Separating chemical and excluded volume interactions of polyethylene glycols with native proteins: comparison with PEG effects on DNA helix formation. Biopolymers. 2015;103:517–527. doi: 10.1002/bip.22662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berg O.G. The influence of macromolecular crowding on thermodynamic activity: solubility and dimerization constants for spherical and dumbbell-shaped molecules in a hard-sphere mixture. Biopolymers. 1990;30:1027–1037. doi: 10.1002/bip.360301104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guttman H.J., Anderson C.F., Record M.T., Jr. Analyses of thermodynamic data for concentrated hemoglobin solutions using scaled particle theory: implications for a simple two-state model of water in thermodynamic analyses of crowding in vitro and in vivo. Biophys. J. 1995;68:835–846. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80260-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharp K.A. Analysis of the size dependence of macromolecular crowding shows that smaller is better. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:7990–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505396112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guinn E.J., Kontur W.S., Record M.T., Jr. Probing the protein-folding mechanism using denaturant and temperature effects on rate constants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:16784–16789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311948110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arakawa T., Timasheff S.N. The stabilization of proteins by osmolytes. Biophys. J. 1985;47:411–414. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83932-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lambert D., Draper D.E. Effects of osmolytes on RNA secondary and tertiary structure stabilities and RNA-Mg2+ interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;370:993–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rees W.A., Yager T.D., von Hippel P.H. Betaine can eliminate the base pair composition dependence of DNA melting. Biochemistry. 1993;32:137–144. doi: 10.1021/bi00052a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nogales E., Wolf S.G., Downing K.H. Structure of the αβ-tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature. 1998;391:199–203. doi: 10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bujacz A. Structures of bovine, equine and leporine serum albumin. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:1278–1289. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912027047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crowther J.M., Lassé M., Dobson R.C. Ultra-high resolution crystal structure of recombinant caprine β-lactoglobulin. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3816–3822. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diamond R. Real-space refinement of the structure of hen egg-white lysozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;82:371–391. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90598-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.