Abstract

Actin-myosin cross-bridges use chemical energy from MgATP hydrolysis to generate force and shortening in striated muscle. Previous studies show that increases in sarcomere length can reduce thick-to-thin filament spacing in skinned muscle fibers, thereby increasing force production at longer sarcomere lengths. However, it is unclear how changes in sarcomere length and lattice spacing affect cross-bridge kinetics at fundamental steps of the cross-bridge cycle, such as the MgADP release rate. We hypothesize that decreased lattice spacing, achieved through increased sarcomere length or osmotic compression of the fiber via dextran T-500, could slow MgADP release rate and increase cross-bridge attachment duration. To test this, we measured cross-bridge cycling and MgADP release rates in skinned soleus fibers using stochastic length-perturbation analysis at 2.5 and 2.0 μm sarcomere lengths as pCa and [MgATP] varied. In the absence of dextran, the force-pCa relationship showed greater Ca2+ sensitivity for 2.5 vs. 2.0 μm sarcomere length fibers (pCa50 = 5.68 ± 0.01 vs. 5.60 ± 0.01). When fibers were compressed with 4% dextran, the length-dependent increase in Ca2+ sensitivity of force was attenuated, though the Ca2+ sensitivity of the force-pCa relationship at both sarcomere lengths was greater with osmotic compression via 4% dextran compared to no osmotic compression. Without dextran, the cross-bridge detachment rate slowed by ∼15% as sarcomere length increased, due to a slower MgADP release rate (11.2 ± 0.5 vs. 13.5 ± 0.7 s−1). In the presence of dextran, cross-bridge detachment was ∼20% slower at 2.5 vs. 2.0 μm sarcomere length due to a slower MgADP release rate (10.1 ± 0.6 vs. 12.9 ± 0.5 s−1). However, osmotic compression of fibers at either 2.5 or 2.0 μm sarcomere length produced only slight (and statistically insignificant) slowing in the rate of MgADP release. These data suggest that skeletal muscle exhibits sarcomere-length-dependent changes in cross-bridge kinetics and MgADP release that are separate from, or complementary to, changes in lattice spacing.

Introduction

In striated muscle, myosin cross-bridges use chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis to provide the force and shortening that is required for muscle contraction. Striated muscle produces greater tension at longer sarcomere lengths, in part due to alterations in thick-to-thin filament overlap and increased Ca2+ sensitivity of thin-filament activation (1, 2, 3). However, cross-bridge kinetics also change with sarcomere length (4, 5), suggesting that myosin behavior may contribute to greater tension production at longer sarcomere lengths. Although these previous findings suggest that myosin kinetics vary with sarcomere length, it is unclear which steps of the cross-bridge cycle may be affected or how these kinetic changes contribute to the length-tension relationship. Thus, length-dependent differences in cross-bridge cycling rates may indicate a length-dependent mechanism that modulates myosin efficiency throughout muscle contraction (i.e., force generated per MgATP hydrolyzed).

Single demembranated (skinned) muscle fibers are widely used to investigate contractile function, because removing the sarcolemma enables precise control and manipulation of the intracellular ionic conditions to investigate cross-bridge behavior. Intact fibers, however, maintain an approximately constant volume as length changes, meaning that increases in fiber length also reduce thick-to-thin-filament lattice spacing, both of which could influence cross-bridge kinetics (6, 7, 8, 9). This relationship is lost as the fibers swell during skinning, though interfilament lattice spacing still decreases to some degree as sarcomere length increases (2, 10). Nonetheless, 3–6% dextran T-500 returns the lattice spacing to in vivo values (11, 12, 13, 14) and can mimic reductions in lattice spacing that would occur as a result of increased sarcomere length (2, 6, 8). Therefore, osmotic compression of skinned fibers via dextran T-500 enables one to separate the individual from the combined effects of sarcomere length and interfilament lattice spacing on cross-bridge cycling kinetics in Ca2+-activated muscle fibers.

Length-dependent muscle properties (such as absolute tension values, Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction, and cross-bridge kinetics) have been identified in both fast- and slow-twitch skeletal tissue (3, 15). Previous experiments in rat psoas fast-twitch muscle revealed that the rate of cross-bridge attachment increased and the rate of detachment decreased at longer sarcomere lengths (2.0 vs. 2.5 μm) (5), and that these values are altered by lattice spacing (6). Here, we expand on these studies by focusing on the length-dependent myosin kinetics of slow-twitch muscle, with additional estimates of cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates in a contracting muscle fiber. For this purpose, the soleus muscle is a convenient tissue due to a high proportion of slow-twitch fibers (16). The optimal sarcomere length of slow-twitch soleus fibers is ∼2.5 μm (17), and they are estimated to work primarily on the ascending limb of the force-length profile (18). Therefore, soleus fibers operating between 2.0 and 2.5 μm sarcomere length produce minimal passive tension and provide an effective model to examine the length-dependent properties of slow-twitch muscle.

To investigate the effect of sarcomere length and interfilament lattice spacing at specific steps of the cross-bridge cycle, we used stochastic length-perturbation analysis to measure myosin kinetics at 2.0 or 2.5 μm sarcomere length in skinned rat soleus fibers, in the presence or absence of 4% dextran T-500. This length-perturbation analysis allows us to measure the stress-strain response of contracting muscle fibers over a broad frequency range using a short burst of band-limited Gaussian noise (19). As sarcomere length varies, frequency-dependent shifts in this stress-strain response result from varied cross-bridge kinetics at specific steps of the cross-bridge cycle. These include MgADP release and MgATP binding rates, which we measured by titrating the [MgATP] of activating solution. We find that the myosin MgADP release rate slows at longer sarcomere length to augment isometric force production in skinned soleus fibers. We also find that sarcomere length influences cross-bridge detachment kinetics more than myofilament lattice spacing due to osmotic compression with dextran. These findings suggest that MgADP release is modulated by sarcomere length, potentially as a result of strain-dependent MgADP release mechanisms. Therefore, a mechanism where MgADP release rate and cross-bridge detachment kinetics change with muscle length may enable more efficient force production per MgATP utilization during locomotion and provide a molecular contribution to the length-tension relationship from myosin per se.

Materials and Methods

Animal models

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington State University and complied with the Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (20–29 weeks old) were acquired from Simonsen Laboratories (Gilroy, CA). Rats were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation (3% volume in 95% O2-5% CO2 flowing at 2 L/min) and both soleus muscles were removed and placed in chilled dissecting solution.

Solutions for skinned skeletal fibers

Muscle mechanics solution concentrations were formulated by solving equations describing ionic equilibria according to Godt and Lindley (20), and all concentrations are listed in millimoles unless otherwise noted. The dissecting solution consisted of 50 BES, 30.83 K propionate, 10 Na azide, 20 EGTA, 6.29 MgCl2, 6.09 ATP, 1 dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 μM Leupeptin, 275 μM Pefabloc, and 1 μM E-64. The skinning solution consisted of dissecting solution with 1% (w/v) Triton-X100 and 50% (w/v) glycerol. The storage solution contained dissecting solution and 50% (w/v) glycerol. The relaxing solution, with pCa 8.0 (pCa = log10[Ca2+]), contained 20 BES, 5 EGTA, 5 MgATP, 1 Mg2+, 0.3 Pi, 35 phosphocreatine, and 300 U/mL creatine kinase, at 200 ionic strength (pH 7.0) adjusted with Na methanesulfonate. The activating solution was the same as the relaxing solution, but with pCa 4.8. The rigor solution was the same as the activating solution, but without MgATP. The osmotic compression solutions were the relaxing, activating, and rigor solutions with the addition of 4% (w/v) dextran T-500. The alkaline phosphatase (AP) solution was the same as the relaxing solution with 6 U/mL recombinant AP from Escherichia coli.

Skinned soleus fiber preparation

Soleus muscles were divided into bundles containing ∼50 fibers and skinned overnight at 4°C, then stored at –20°C in the storage solution (containing 50% glycerol) for up to 3 weeks. Individual fibers were pulled out from the bundles using forceps, and each end was secured with an aluminum T-clip, then pretreated for 10 min in AP solution at room temperature to minimize any variations in basal phosphorylation of myofilament proteins. Fibers were mounted between a piezoelectric motor (P841.40, Physik Instrumente, Auburn, MA) and a strain gauge (AE801, Kronex, Walnut Creek, CA) in a chamber maintained at 17°C. In a 2 × 2 experimental design, fibers were lowered into a 30 μL droplet of relaxing solution containing either 0 or 4% dextran and stretched to either 2.0 or 2.5 μm sarcomere length as measured by digital Fourier transform (IonOptix, Milton, MA). Fibers were calcium activated from pCa 8.0 to pCa 4.8 with 5 mM MgATP and then titrated toward rigor by reducing [MgATP]. At least three fibers were included at each condition from each of the four rats.

Dynamic mechanical analysis

Stochastic length perturbations were applied for a period of 60 s as previously described (19, 21), using an amplitude distribution with a standard deviation of 0.05% muscle lengths over the frequency range 0.5–250 Hz. Elastic and viscous moduli, E(ω) and V(ω), were measured as a function of angular frequency (ω) from the in-phase and out-of-phase portions of the tension response to the stochastic length perturbation. The complex modulus, Y(ω), was defined as E(ω) + iV(ω), where i = √−1. Fitting Eq. 1 to the entire frequency range of modulus values provided estimates of six model parameters (A, k, B, 2πb, C, and 2πc).

| (1) |

The A-term in Eq. 1 reflects the viscoelastic mechanical response of passive structural elements in the muscle and holds no enzymatic dependence. The parameter A represents the combined mechanical stress of the strip, whereas the parameter k describes the viscoelasticity of these passive elements, where k = 0 represents a purely elastic response and k = 1 is a purely viscous response (22, 23). The B- and C-terms in Eq. 1 reflect enzymatic cross-bridge cycling behavior that produces frequency-dependent shifts in the viscoelastic mechanical response during Ca2+-activated contraction. These B- and C- processes characterize work-producing (cross-bridge attachment) and work-absorbing (cross-bridge detachment) muscle mechanics, respectively (6, 24, 25, 26). The parameters B and C represent the mechanical stress from the cross-bridges (number of cross-bridges formed × mean cross-bridge stiffness), and the rate parameters 2πb and 2πc reflect cross-bridge kinetics that are sensitive to biochemical perturbations affecting enzymatic activity, such as [MgATP], [MgADP], or [Pi] (27). Molecular processes contributing to cross-bridge attachment or force generation underlie the cross-bridge attachment rate, 2πb. Similarly, processes contributing to cross-bridge detachment or force decay underlie the cross-bridge detachment rate, 2πc.

Stochastic system analysis provides a portrait of cross-bridge kinetics as a function of [MgATP]. Assuming that the myosin attachment events include time spent in the MgADP state and in the rigor state as [MgATP] is titrated toward rigor, the cross-bridge detachment rate can be described by

| (2) |

As explained in detail by Tyska and Warshaw (28) and implemented in our previous publications (21, 29), fitting the 2πc-[MgATP] relationship to Eq. 2 allows a calculation of 1) k−ADP, which represents the cross-bridge MgADP release rate and the asymptotic maximal myosin detachment rate per second (s−1) at saturating [MgATP]; 2) k+ATP, which represents the second-order cross-bridge MgATP binding rate per myosin concentration in M−1 s−1); and 3) the ratio k−ADP/k+ATP, which represents the concentration of MgATP producing half the maximal myosin detachment rate (i.e., [MgATP]50).

Statistical analysis

All values are shown as the mean ± SE. Sequential quadratic programming methods in Matlab (v. 7.9.0, The Mathworks, Natick MA) was used for constrained nonlinear least-squares fitting of Eqs. 1 and 2 to moduli, whereas statistical comparisons were performed using SPSS (IBM Statistics, Chicago, IL). The effects of dextran and sarcomere length on the three-parameter Hill fits to the tension-pCa relationships and the parameter estimates for the nucleotide handling rates were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance. All other relationships were analyzed using linear mixed models with main effects of dextran and sarcomere length, and pCa, frequency, or [MgATP] as a repeated measure where appropriate. Whenever these main effects or their interactions were significant, we followed these analyses with a least-significant-difference post hoc comparison of the means between dextran and sarcomere length. Statistical significance is reported at p < 0.05.

Results

Effects of sarcomere length and dextran on tension development

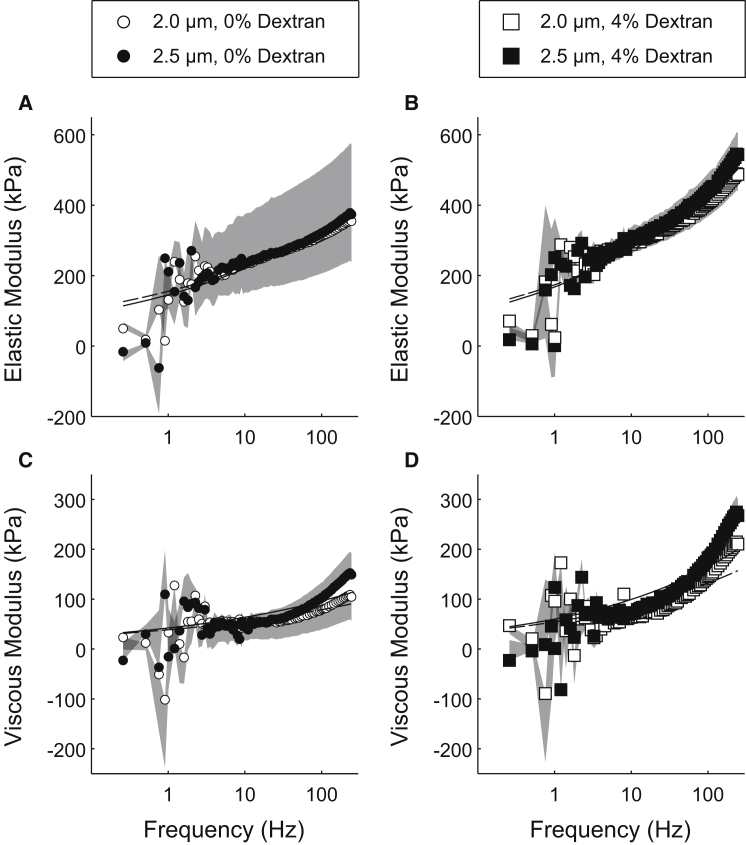

As [Ca2+] was titrated from pCa 8.0 (relaxed) to pCa 4.8 (maximally activated), isometric tension increased in a sigmoidal manner, which was fit to a three-parameter Hill equation. In the absence of dextran, maximal Ca2+-activated tension was ∼20% greater in fibers at 2.5 μm sarcomere length compared to 2.0 μm sarcomere length (83.28 ± 5.21 kN m−2 vs. 68.36 ± 4.53 kN m−2; p = 0.038). Activated tension values were also consistently larger at Ca2+ concentrations greater than pCa 5.8 (Fig. 1 A; Table 1). Relaxed tension values were not significantly different between the two sarcomere lengths (p = 0.759) due to a nearly flat passive-tension-versus-length relationship at these sarcomere lengths (30). There was an increase in the calcium sensitivity of force at greater sarcomere length, shown by a shift in the pCa50 to 5.68 ± 0.01 from 5.60 ± 0.01 at 2.0 μm vs. 2.5 μm sarcomere length (p = 0.019; Table 1). These findings suggest that length-dependent increases in active tension did not arise from alterations in passive elements of the sarcomeres being stretched between 2.0 and 2.5 μm, but rather stem from length-dependent increases in Ca2+-activated cross-bridge binding in the absence of dextran.

Figure 1.

Dextran and longer sarcomere length both increased tension according to the tension-pCa relationship. (A) Ca2+-activated tension-pCa relationship at 2.0 μm and 2.5 μm sarcomere lengths in solution containing 0% dextran. (B) Ca2+-activated tension-pCa relationship at 2.0 μm and 2.5 μm sarcomere length in solution containing 4% dextran. The dashed line is for comparison with 2.0 μm fibers in 0% dextran solution. Fits are to the three-parameter Hill equation. ∗p < 0.05 between sarcomere lengths.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Tension-pCa Relationships in Rat Soleus Fibers at 2.0 and 2.5 μm Sarcomere Lengths, with and without Dextran Treatment

| 2.0 μm | 2.5 μm | 2.0 μm, Dextran | 2.5 μm, Dextran | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmin (kN/m2) | 0.44 ± 0.30 | 2.61 ± 0.33 | 3.33 ± 0.72 | 5.61 ± 1.07 |

| Tmax (kN/m2) | 68.80 ± 4.55 | 85.90 ± 5.13a | 90.58 ± 10.47b | 104.21 ± 9.77b |

| Tdev (kN/m2) | 68.36 ± 4.53 | 83.28 ± 5.21a | 87.26 ± 10.76b | 98.60 ± 9.71b |

| pCa50 | 5.60 ± 0.01 | 5.68 ± 0.01a | 5.78 ± 0.04b | 5.83 ± 0.03b |

| nH | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.4 |

| Maxfit (kN/m2) | 67.95 ± 4.31 | 81.15 ± 5.17 | 98.20 ± 13.63a | 97.69 ± 10.77 |

| n fibers | 17 | 23 | 15 | 20 |

All values other than number of fibers are represented as the mean ± SE. Maxfit, pCa50, and nH represent fit parameters to a three-parameter Hill equation for the Tdev-pCa relationship: . Tmin, absolute tension value at pCa 8.0; Tmax, absolute tension value at pCa 4.8; Tdev, Ca2+-activated, developed tension (Tmax – Tmin).

p < 0.05 effect of sarcomere length under similar treatment conditions.

p < 0.05 effect of 4% dextran treatment at the same sarcomere length.

In the presence of 4% dextran, there was greater activated tension at submaximal [Ca2+] for 2.5 μm sarcomere length fibers compared to 2.0 μm, though it was not significant at maximal [Ca2+] (98.60 ± 9.71 N m−2 vs. 87.26 ± 10.76 N m−2; p = 0.156; Fig. 1 B; Table 1). There was not a significant increase in the pCa50 value as sarcomere length increased with 4% dextran (5.83 ± 0.03 vs. 5.78 ± 0.04; p = 0.164). When comparing the effect of dextran on the pCa-tension relationship for fibers with the same sarcomere length, 4% dextran increased maximal tension (p = 0.019 at 2.0 μm; p = 0.033 at 2.5 μm) and calcium sensitivity (p < 0.001 at 2.0 μm; p < 0.001 at 2.5 μm). Neither sarcomere length nor dextran had a significant effect (p = 0.515 and p = 0.193, respectively) on the slope of the fit, nH, suggesting that cooperativity of myosin binding was unchanged by sarcomere length or lattice spacing (Table 1).

Effects of sarcomere length and dextran on viscoelastic mechanical properties

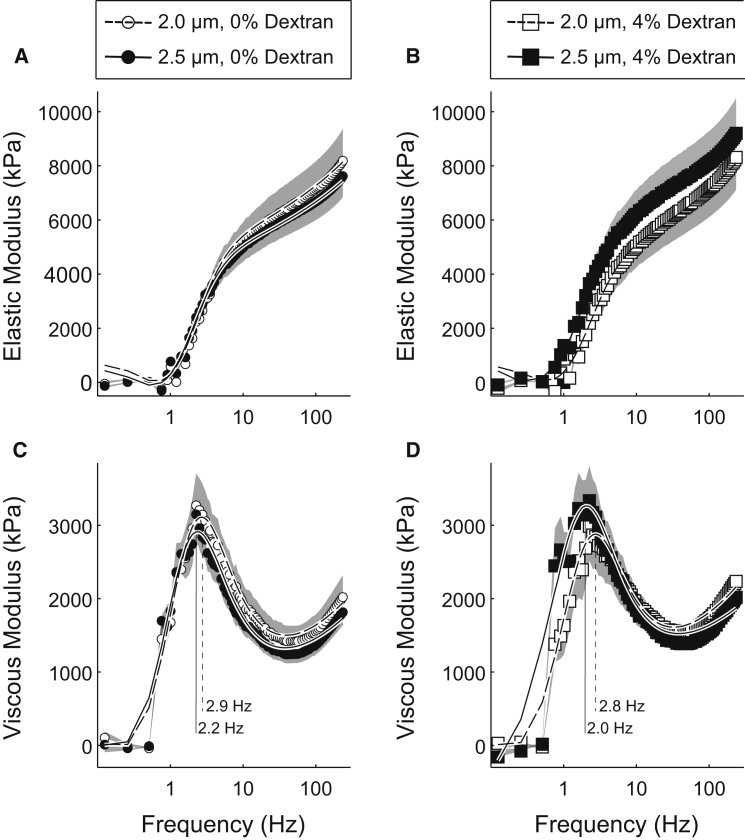

Under relaxed conditions (pCa 8.0, MgATP = 5 mM), neither sarcomere length nor dextran had a significant effect on viscoelastic mechanical stiffness of the muscle fibers (Fig. 2). Under maximally activated conditions without dextran (pCa 4.8, MgATP = 5 mM), elastic modulus values were not different at any particular frequency between 2.5 μm and 2.0 μm sarcomere lengths (Fig. 3 A). Viscous modulus values also showed few differences, except for a small, consistent shift toward lower frequencies for the overall modulus-frequency relationship for 2.5 μm sarcomere length fibers (Fig. 3 C). The overall shape of the modulus-frequency response represents a broad metric of cross-bridge cycling kinetics, where a shift toward lower frequencies demonstrates slower cross-bridge cycling and a shift toward higher frequencies demonstrates faster cross-bridge cycling. Therefore, these data indicate slower cross-bridge cycling for the fibers at 2.5 μm sarcomere length compared to those at 2.0 μm in the absence of dextran. Like the 0% dextran data, there were no differences in the magnitude of the elastic or viscous modulus values at any single frequency as sarcomere length increased from 2.0 to 2.5 μm for fibers in 4% dextran (Fig. 3, B and D). However, the overall shift toward lower frequencies in these modulus-frequency responses persisted at the longer sarcomere length, indicating slower cross-bridge cycling at 2.5 vs. 2.0 μm sarcomere length in 4% dextran.

Figure 2.

Dextran and sarcomere length did not influence viscoelasticity under relaxed conditions. Elastic (top) and viscous (bottom) moduli were plotted against frequency for 2.0 μm and 2.5 μm sarcomere length at pCa 8 and 5 mM [MgATP]. (A and C) Elastic and viscous moduli for fibers in dextran-free solution. (B and D) Elastic and viscous moduli for fibers in solution containing 4% dextran. Gray shading represents single-sided error bars (upward for 2.0 μm sarcomere length and downward for 2.5 μm sarcomere length) associated with the mean data points at each frequency.

Figure 3.

Sarcomere length influenced viscoelasticity under activated conditions. Elastic (top) and viscous (bottom) moduli were plotted against frequency for 2.0 μm and 2.5 μm sarcomere length at pCa 4.8 and 5 mM [MgATP]. (A and C) Elastic and viscous moduli for fibers in dextran-free solution. (B and D) Elastic and viscous moduli for fibers in solution containing 4% dextran. Leftward shifts in the C-process of the viscous modulus indicate slower myosin detachment rates. Gray shading represents single-sided error bars (upward for 2.0 μm sarcomere length and downward for 2.5 μm sarcomere length) associated with the mean data points at each frequency.

Effects of sarcomere length and dextran on fiber kinetics as [ATP] varies

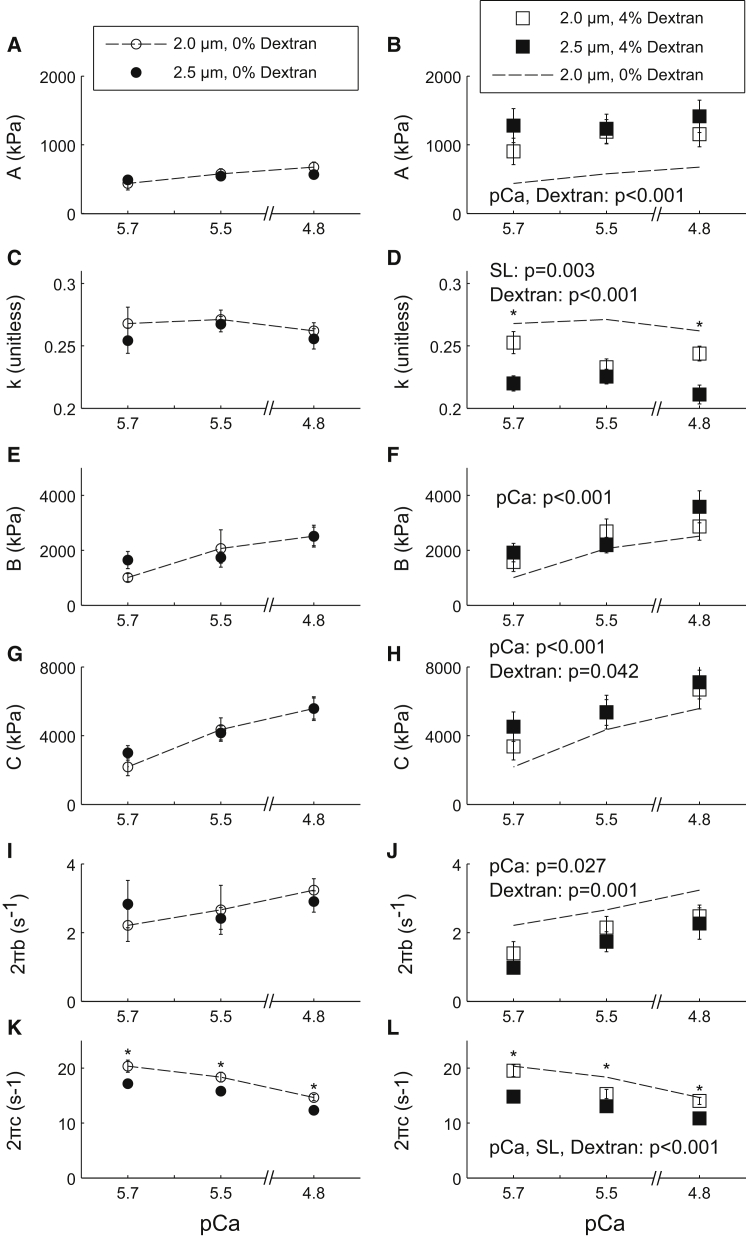

Modulus values were fit to Eq. 1 to extract model parameters related to viscoelasticity (Eq. 1, A-term), cross-bridge binding (Eq. 1, B- and C-terms), and cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and 2πc) as the fibers were titrated toward rigor (5.0–0.05 mM MgATP, pCa 4.8). The resulting fit parameters are plotted against [MgATP] in Fig. 4, with p-values listed in each plot for significant effects of [MgATP], sarcomere length, dextran, or interactions between these main effects. As [MgATP] was titrated toward rigor in 0% dextran solutions, values for parameter A increased (p < 0.001), indicating an expected increase in viscoelastic stiffness as a greater number of cross-bridges remain strongly bound at low [MgATP] (Fig. 4 A). There was also a decrease in the value of k as [MgATP] decreased (p < 0.001), indicating an expected increase in the elastic characteristic of the fiber due to greater cross-bridge binding (Fig. 4 C). The values of parameters B and C increased as [MgATP] was titrated toward rigor (p = 0.001 and p = 0.019, respectively), representing increased cross-bridge binding. Consistently, B values were greater for fibers at 2.5 μm than at 2.0 μm sarcomere length (Fig. 4, E and G), also suggesting increased cross-bridge binding at longer sarcomere lengths in the absence of dextran.

Figure 4.

Sarcomere length and dextran both influenced cross-bridge kinetics as [MgATP] was varied. Parameter fits to Eq. 2 are plotted against [MgATP] for fibers of 2.0 μm and 2.5 μm sarcomere lengths at pCa 4.8 in 0% dextran (left column) and 4% dextran solutions (right column). Dashed lines are for comparison with 2.0 μm fibers in 0% dextran solution. (A–D) Increases in A and decreases in k as [MgATP] decreases are representative of increased viscoelastic stiffness and fiber elasticity. (E–H) Increases in the magnitude parameters B and C at lower [MgATP] indicate increases in cross-bridge binding. (I–L) Decreases in 2πb and 2πc as [MgATP] decreases toward rigor represent slower rates of myosin attachment and detachment rates, respectively. ∗p < 0.05 between sarcomere lengths.

As further discussed below, there was a small, but significant, slowing in the 2πb-MgATP relationship among all four conditions (Fig. 4, I and J, p = 0.011 for [MgATP]). This statistic was primarily driven by the dextran effects, as the rate of cross-bridge attachment (2πb) did not change significantly with [MgATP] in the absence of dextran (p = 0.398 for a main effect of MgATP among the 0% dextran data in Fig. 4 I). Consistently, the rate of cross-bridge attachment did not change with sarcomere length (p = 0.125 for a main effect of sarcomere length, Fig. 4, I and J). The rate of cross-bridge detachment, 2πc, decreased as [MgATP] was titrated toward rigor (p < 0.001), due to the increasingly longer time that cross-bridges spent in the rigor state as [MgATP] decreased (Fig. 4, I and J). These cross-bridge detachment rates were also slower at 2.5 μm than at 2.0 μm sarcomere length (p = 0.002). This suggests a slower rate of MgADP dissociation from myosin at longer sarcomere length in both the absence and presence of dextran.

As [MgATP] was titrated toward rigor in 4% dextran solution, the effects of [MgATP] and sarcomere length on parameter values were largely similar to the results for 0% dextran. However, compared to 0% dextran conditions, fibers in 4% dextran had significantly greater values for A (p < 0.001) and decreased values of k (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4, B and D). Parameters B and C were not significantly affected by dextran (p = 0.319 and p = 0.941, respectively; Fig. 4, G and H). As introduced just above, there was also a slight MgATP effect in the 2πb-MgATP relationship (p = 0.002 for the 4% dextran conditions (Fig. 4 J)), showing an ∼1 s−1 slowing in cross-bridge attachment rate across the range 0.5–5 mM [MgATP]. The rates of cross-bridge attachment (2πb (Fig. 4, I and J)) and detachment (2πc (Fig. 4, K and L)) were both slower in the presence of 4% dextran compared to 0% dextran (both p < 0.001). This latter finding is consistent with previous measurements showing that cross-bridge kinetics slow with osmotic compression of the myofilament lattice in fast-twitch muscle fibers (5, 6), and it may have some cross-correlation with an MgATP-dependent slowing of 2πb in the presence of dextran.

Effects of sarcomere length and dextran on myosin detachment-rate kinetics

The relationships between myosin detachment rate (2πc) and [MgATP] were fit to Eq. 2 to estimate transition rates in the cross-bridge cycle, specifically the cross-bridge rate of MgADP release (k−ADP) and the cross-bridge rate of MgATP binding (k+ATP). The rate of MgADP release was ∼20% slower in fibers at 2.5 μm vs. 2.0 μm sarcomere length in both 0% dextran (11.2 ± 0.5 vs. 13.5 ± 0.7 s−1, respectively; p = 0.010) and 4% dextran (10.1 ± 0.6 vs. 12.9 ± 0.5 s−1, respectively; p = 0.002; Table 2). In the absence of dextran, increasing sarcomere length to 2.5 μm slowed the rate of MgATP binding by 45% (p = 0.044). With 4% dextran, however, the MgATP binding rate did not slow significantly as sarcomere length increased (p = 0.506).

Table 2.

Estimates of Myosin Cross-Bridge Kinetics from Fits of the Cross-Bridge Detachment Rate 2πc versus MgATP Relationships to Eq. 2 for 2.0 and 2.5 μm Sarcomere Lengths

| 2.0 μm | 2.5 μm | 2.0 μm, Dextran | 2.5 μm, Dextran | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k−ADP (s−1) | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 11.2 ± 0.5a | 12.9 ± 0.5 | 10.1 ± 0.6a |

| k+ATP (mM−1 s−1) | 504.3 ± 119.3 | 273.3 ± 36.7a | 170.1 ± 46.3b | 134.1 ± 29.5 |

| [MgATP]50 (μM) | 64.3 ± 15.0 | 66.1 ± 10.1 | 171.6 ± 50.3b | 119.2 ± 20.0 |

| t−ADP (ms) | 76.7 ± 3.5 | 95.2 ± 5.7a | 79.4 ± 3.6 | 103.5 ± 6.1a |

All values other than number of fibers are represented as the mean ± SE. Terms are defined as follows: k-ADP, cross-bridge MgADP release rate; k+ATP, cross-bridge MgATP binding rate; [MgATP]50 = k−ADP/k+ADP, MgATP concentration at the half-maximal detachment rate; t−ADP = 1/k-ADP, myosin cross-bridge attachment duration for the MgADP state.

p < 0.05 effect of sarcomere length under similar treatment conditions.

p < 0.05, effect of dextran treatment at the same sarcomere length.

Effects of sarcomere length and dextran on fiber kinetics as [Ca2+] varies

Modulus values were fit to Eq. 1 to extract model parameters related to viscoelasticity, cross-bridge binding, and cross-bridge kinetics as the fibers were titrated from pCa 8.0 (relaxed) to pCa 4.8 (activated) in 5 mM [MgATP]. As [Ca2+] was titrated toward full activation in 0% dextran solution, values for parameter A increased (p = 0.003), indicating an expected increase in viscoelastic stiffness as a greater number of cross-bridges are formed. However, there was no significant difference in the values of A between 2.5 μm and 2.0 μm sarcomere length fibers (p = 0.859; Fig. 5 A). The parameters of cross-bridge binding, B and C, both increased at higher [Ca2+] (p = 0.019 and p < 0.001, respectively), though without a significant effect of sarcomere length (p = 0.188 and p = 0.998, respectively; Fig. 5, E and G). The rate of cross-bridge attachment, 2πb, increased with [Ca2+] (p = 0.042), but not with sarcomere length (p = 0.945; Fig. 5 I). The cross-bridge detachment rate, 2πc, slowed as [Ca2+] was titrated toward full activation (p < 0.001), and was significantly slower at 2.5 μm than at 2.0 μm sarcomere lengths (p = 0.002; Fig. 5 K).

Figure 5.

Sarcomere length and dextran both influenced cross-bridge kinetics as pCa is varied. Parameter fits to Eq. 2 are plotted against pCa for fibers of 2.0 μm and 2.5 μm sarcomere lengths in 5mM [MgATP] solution containing 0% dextran (left column) or 4% dextran (right column). Dashed lines are for comparison with 2.0 μm fibers in 0% dextran solution. (A–D) Increases in A and decreases in k as [Ca2+] decreases are representative of increased viscoelastic stiffness and fiber elasticity. (E–H) Increases in the magnitude parameters B and C at lower [Ca2+] indicate increases in cross-bridge binding. (I–L) Decreases in 2πb and 2πc as [MgATP] decreases from 4.8 pCa represent slower rates of myosin attachment and detachment rates, respectively. ∗p < 0.05 between sarcomere lengths.

As fibers were titrated toward full activation in 4% dextran solution, the effects of [Ca2+] and sarcomere length on parameter values were largely similar to the results for 0% dextran. In the presence of 4% dextran, there was a significant effect of dextran on parameter A, resulting in larger values than in 0% dextran (p < 0.001; Fig. 5, A and B). Similarly, k was smaller in 4% dextran than in 0% dextran (p < 0.001), representing an increase in the elastic characteristic of viscoelastic fiber stiffness, and there was a significant effect of sarcomere length on k in 4% dextran (p = 0.003; Fig. 5, C and D). Parameter C was slighter larger in the presence of dextran, though parameter B was not significantly different between the dextran conditions (Fig. 5, E–H). Both the rate of cross-bridge attachment, 2πb, and the rate of cross-bridge detachment, 2πc, were slower in 4% dextran compared to 0% (p = 0.001 and p = 0.042, respectively; Fig. 5, I–L)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of sarcomere length and lattice spacing on the cross-bridge cycling kinetics in skinned soleus fibers from rats. Maximal tension, sensitivity to activator Ca2+, and the cross-bridge cycling rate can be affected by changes in sarcomere length and lattice spacing in skeletal fibers (4, 17, 30). Herein we show that the cross-bridge detachment rate is slowed at longer sarcomere length due to slower MgADP release from myosin, irrespective of myofilament lattice spacing (i.e., length-dependent slowing of MgADP release occurs both with and without osmotic compression from dextran T-500). This finding has important implications for myosin force production and ATP utilization as sarcomere length changes throughout a contraction. Slower MgADP release at longer sarcomere length also provides supporting evidence for a strain-dependent MgADP release mechanism in slow-twitch skeletal fibers, consistent with single-molecule optical trap measurements describing this mechanism in multiple muscle myosin isoforms (31, 32, 33, 34).

The MgADP release rate is the primary determinant of cross-bridge attachment duration under saturating ATP conditions and sets the maximum shortening velocity for muscle fibers (28, 35, 36). We measured a slower rate of myosin MgADP release at 2.5 μm compared to 2.0 μm sarcomere lengths in our maximally Ca2+-activated fibers (Table 2). This slowed dissociation rate decreased the apparent myosin cross-bridge detachment rate (2πc; Fig. 4 K) by ∼15% at a longer sarcomere length in the absence of dextran. This finding is consistent with measurements using fast-twitch rabbit psoas fibers, which showed that cross-bridge detachment rate decreased ∼9% at 2.5 μm compared to 2.0 μm sarcomere lengths (5). A decreased MgADP release rate would result in myosin cross-bridges spending longer time in the strongly bound, force-generating phase of the cross-bridge cycle. As a consequence, cross-bridges with slower MgADP release rates would also exhibit a higher myosin duty ratio that could produce greater force per cross-bridge cycle. We observed greater Ca2+-activated tension at 2.5 μm than at 2.0 μm sarcomere length, consistent with the idea that slowed MgADP release may effectively enhance myosin force production throughout the cross-bridge cycle. We also observed slower myosin detachment rates in longer sarcomere length fibers at submaximal [Ca2+] (pCa 5.7 and 5.5, MgATP = 5 mM; Fig. 5 K), suggesting that length-dependent changes in the myosin duty ratio at submaximal [Ca2+] were also consistent with the kinetic observations at saturating [Ca2+]. Sarcomere-length-dependent slowing of cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates, and the associated increases in myosin force production, may provide a molecular mechanism to enhance contractility and economy of contraction at longer sarcomere length.

We also observed length-dependent relationships in both the rate of myosin detachment and the rate of MgADP release when fibers were osmotically compressed with 4% dextran. Under these conditions, myosin detachment rate was ∼20% slower at 2.5 μm than at 2.0 μm sarcomere length in fully activated (pCa 4.8, MgATP = 5 mM; Fig. 4 L) fibers. Compared to data in 0% dextran, 4% dextran slowed the myosin detachment rate (2πc) by ∼10% in fibers at 2.5 μm sarcomere length, consistent with previous findings (9). However, myosin detachment rates were not different in the presence or absence of dextran at 2.0 μm sarcomere length. These changes in detachment rate were predominantly driven by sarcomere-length-dependent slowing of the MgADP release rate with and without dextran, as MgADP release rates were similar at each sarcomere length with or without dextran (Table 2). The findings here are comparable to previous measurements in rabbit fast-twitch fibers, which showed only small changes in MgADP dissociation kinetics at moderate levels of dextran compression (<6.3%), but larger effects on these kinetics at high levels of dextran compression (9%) (6). These observations suggest that although decreased lattice spacing can slow myosin detachment, increased sarcomere length has a greater effect on cross-bridge kinetics than osmotic compression of the fibers, especially on MgADP release.

The MgATP-dependent cross-bridge detachment rates from skinned rat soleus fibers at 17°C (Fig. 4 K) are consistent with the 2πc-MgATP relationships measured in skinned rabbit soleus fibers at 20°C (37, 38). Specifically, we show that the myosin detachment rate increased from 8.8 to 14.6 s−1 (≈1.7-fold increase) over the range 0.05–5 mM [MgATP] at 2.0 μm sarcomere length, and from 6.4 to 12.3 s−1 at 2.5 μm (≈1.9-fold increase) sarcomere length. Estimated rate values from comparable measurements from rabbit soleus fibers show that 2πc increased from ∼14 to 22 s−1 (≈1.6-fold increase) as [MgATP] increased from 0.05 to 5 mM at 20°C (37, 38). Comparable measurements from rabbit soleus fibers at 37°C show that 2πc increased from ∼83 to 190 s−1 (≈2.3-fold increase) as [MgATP] increased from 0.05 to 5 mM (37), illustrating a Q10 of 2.4–2.9 for type I rabbit myosin that may vary slightly with [MgATP]. This Q10 value is partially responsible for the slightly faster detachment kinetics in the rabbit soleus fibers at 20°C (37) compared to rat soleus fibers at 17°C (Fig. 4 K), although species-specific myosin differences may also contribute to the minor kinetic differences between these studies.

Our estimated values of cross-bridge MgADP dissociation and MgATP binding rates (Table 2) are slower than comparable kinetic estimates from stopped-flow measurements using purified type I myosin or myosin-S1 from multiple species. Estimates of MgADP dissociation rates range from 48 s−1 in pig soleus to 94 s−1 in bovine masseter at 20°C (39, 40), which is roughly four- to sixfold faster than our estimates. These findings suggest that myosin cross-bridge kinetics and nucleotide handling rates are influenced by organizational structure of the myofilament lattice, which may slow cross-bridge cycling kinetics as force develops throughout the sarcomere in muscle fibers (or with reduced thick-to-thin-filament spacing) (6, 8). Therefore, there may be strain-dependent or load-dependent cross-bridge behavior that contributes to the estimated cross-bridge detachment and nucleotide handling rates, which we cannot directly quantify due to the kinetic assumptions underlying Eq. 2 being insensitive to load or the number of bound cross-bridges as tension varies under maximally activated [Ca2+] in a muscle fiber. Nonetheless, this study extends measurements of cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates using skeletal muscle fibers, and these findings begin to suggest that changes in sarcomere length may modulate cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates as muscles shorten or lengthen during physiological locomotion.

The presence of the sarcolemma in intact striated fibers enables the cell to maintain an approximately constant volume as length changes, producing an inverse relationship between sarcomere length and interfilament lattice spacing (11, 15, 41, 42, 43). In demembranated fibers, however, the permeabilized sarcolemma cannot maintain a constant volume, and lattice spacing is determined by a combination of sarcomere length, solution composition, and physical constraints, as well as attractive and repulsive forces between the filaments (11). After the membrane is permeabilized, the myofilament lattice swells, but thick-to-thin-filament spacing can be restored to its original size through osmotic compression with 3–6% dextran T-500 (11, 44). Thus, it is possible that decreased filament spacing slows MgADP release by reducing radial strain on the myosin heads and prolonging the strongly bound, force-generating phase of the cross-bridge cycle (45, 46, 47). However, our data suggest that increases in sarcomere length (2.5 μm vs. 2.0 μm) have a greater influence on the myosin ADP release rate than the reduction of lattice spacing via 4% dextran (Table 2). A number of studies have also suggested that length-dependent increases in tension and Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction are not exclusively dependent on decreased lattice spacing as sarcomere length increases (3, 13). Although these prior studies did not measure cross-bridge kinetics, our kinetics data support the idea that length-dependent increases in force production may not be entirely explained by decreases in myofilament lattice spacing.

It has been well established that increases in sarcomere length result in greater Ca2+ sensitivity of force production in striated muscle, including slow-twitch soleus fibers (30). A prominent theory explaining this phenomenon is that reduced lattice spacing leads to more favorable formation of strongly bound cross-bridges at a given [Ca2+] (3, 13, 48). Our data support this idea, as we measured increased Ca2+ sensitivity of fibers at 2.5 μm vs. 2.0 μm sarcomere lengths in the absence of dextran (Fig. 1 A). Additional reports show that Ca2+-sensitivity of force still increases with sarcomere length even when lattice spacing is controlled for by osmotic compression of the filament lattice (3, 49). This latter finding suggests that length-dependent mechanisms of Ca2+ sensitivity may have more to do with changes in sarcomere length than with changes in interfilament spacing (3). However, osmotic compression of the myofilament lattice also increases Ca2+ sensitivity of force without any changes in sarcomere length (3, 50). This relationship between osmotic compression and Ca2+ sensitivity has been suggested to be a combined result of decreased interfilament spacing and conformational changes in the thick filament that may increase the number of myosin heads in the weakly bound state (showing an effect with as little as 1% dextran that remains relatively constant at higher dextran concentrations) (50). Consistently, we observed that 4% dextran increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force at both 2.0 μm and 2.5 μm sarcomere length, compared to no dextran treatment (Fig. 1 B; Table 1). However, the effect of sarcomere length on maximal tension production and Ca2+ sensitivity of tension was suppressed when fibers were compressed with 4% dextran (versus in the absence of dextran). Altogether, these findings indicate that changes in sarcomere length have pronounced effects on muscle mechanics that cannot be sufficiently explained by reductions in myofilament lattice spacing alone.

We also observed an effect of both sarcomere length and osmotic compression on cross-bridge kinetics when fibers were submaximally Ca2+-activated (pCa 5.7 and 5.5). Across all conditions, parameter A increased with [Ca2+], indicating an increase in viscoelastic stiffness due to increased cross-bridge binding (in combination with the associated increases in parameters B and C). In addition, the rate of cross-bridge attachment (2πb) was faster as [Ca2+] increased, due to the Ca2+-dependent nature of cross-bridge binding (51). This attachment rate also slowed when the myofilament lattice was compressed with 4% dextran (Fig. 5 I and J), consistent with previous studies showing that dextran slows cross-bridge cycling rates (8, 9). The rate of cross-bridge detachment (2πc) was consistently slower as [Ca2+] increased (Fig. 5, K and L). Although cross-bridge detachment is primarily considered an ATP-mediated event, this finding supports the theory that [Ca2+] may influence myosin detachment through thin-filament interactions, wherein decreased [Ca2+] promotes a stronger interaction between troponin-I and actin that favors myosin detachment (52). It is also possible that myosin attachment and detachment kinetics change with the number of cross-bridges available to engage with the thin filament due to Ca2+-regulated and/or tension-mediated activation pathways between the thick and thin filaments (53, 54). This combination of slower cross-bridge attachment and faster detachment rates at submaximal [Ca2+] may not significantly alter the overall cross-bridge cycling rate and shortening velocity in a muscle fiber. Altogether, the effects of sarcomere length and dextran on cross-bridge kinetics are largely similar at submaximal and maximal [Ca2+], indicating that cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates slow as sarcomere length increases at physiological activation levels (55).

Slowed MgADP release may be the result of combinatorial effects between reduced lattice spacing and other length-dependent mechanisms. Although increased sarcomere length is well correlated with reduced lattice spacing, it has also been shown to alter filament organization, filament extensibility, and orientation of myosin heads (56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61). As sarcomere length increases, greater forces are distributed throughout the sarcomere to stabilize myofilament lattice organization and diminish myofilament extensibility (56, 60, 61) with increasingly greater tension development in a muscle fiber. Recent studies also suggest that force-dependent or load-dependent activation pathways between the thick and thin filaments regulate the number of cross-bridges that are “activated” or “primed” for binding available actin-target sites (53, 54). Thus, it is likely that these structural alterations to the myofilaments also influence load-dependent mechanisms of MgADP release to slow cross-bridge detachment. Further studies have suggested that release of MgADP requires additional movement of the myosin head after the power stroke to induce a conformational change in the nucleotide binding pocket, freeing MgADP (31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 62). This “double step” was observed in both slow and fast skeletal myosins, and was associated with MgADP release from myosin, in single-molecule optical trap experiments (31). If MgADP release depends on a conformational change that is coupled to additional movement of the lever arm, then increased load borne by a cross-bridge would impede MgADP dissociation and slow cross-bridge detachment rate (36, 62). Our measured cross-bridge detachment rates slow as maximal fiber tension increase, which is consistent with the idea that MgADP release slows in these fibers due to greater load and/or strain that cross-bridges experience at longer sarcomere length during isometric contraction. This length-dependent mechanism in a muscle fiber would be consistent with load-dependent MgADP release mechanics from single myosin measurements.

A portion of the load and strain experienced by bound myosin heads as they generate force depends upon the distribution of fiber tension throughout the sarcomere (along the thick and thin filaments). Thus, greater tension values will lead to increasingly greater load borne along the filaments and a concomitant decrease in myofilament extensibility that is inversely related to the increasingly greater extension or distortion occurring along thick-filaments bearing increasingly greater loads (56, 60, 61). One could speculate that these increases in filament load and decreases in filament extensibility that stem from increased sarcomere length and dextran compression could 1) increase the load opposing a myosin power stroke, thereby slowing cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates, or 2) stabilize the sarcomere organization to stabilize cross-bridge binding at greater strains to enable completion of a slower power stroke that generates greater force (36, 56, 62). Therefore, mechanisms that prolong and stabilize cross-bridge binding at the molecular level are linked with spatial and mechanical characteristics of the myofilament lattice that enable greater tension production at the fiber level with increased sarcomere length and/or myofilament lattice compression.

Conclusions

Skinned soleus fibers from rats were stretched to either 2.0 μm or 2.5 μm sarcomere length while cross-bridge kinetics and nucleotide handling were measured using stochastic length-perturbation analyses during isometric contraction. Myosin detachment and MgADP release rates were slower at 2.5 μm vs 2.0 μm sarcomere length at both submaximal and saturating [Ca2+] in the absence of dextran. Myosin detachment and MgADP release rates were also slower at 2.5 μm vs 2.0 μm sarcomere length when fibers were compressed with 4% dextran T-500. However, we did not observe significant differences in these rates between fibers at the same sarcomere length with and without dextran. These data suggest that detachment of myosin from actin is slowed as sarcomere length increases due to slower cross-bridge MgADP release rate, but that this process may not be tied exclusively to changes in myofilament lattice spacing. At a longer sarcomere length, the greater forces borne by the myofilaments diminish their relative extensibility, thereby increasing the load that myosin experiences throughout a cross-bridge cycle. This enhanced load or molecular strain on the motor domain may slow the series of conformational changes required for MgADP release from the nucleotide binding pocket and slow cross-bridge detachment rates. This mechanism may serve to enhance the efficiency of MgATP utilization at longer sarcomere length by prolonging the time myosin spends in the strongly bound, force-generating phase of the cross-bridge cycle.

Author Contributions

A.J.F. and B.C.W.T. conceived and designed the research; A.J.F. and S.R.L. performed experiments; A.J.F., S.R.L., and B.C.W.T. analyzed data; A.J.F. and B.C.W.T. interpreted results of experiments; A.J.F. and B.C.W.T. prepared figures; A.J.F. drafted manuscript; A.J.F. and B.C.W.T. edited and revised manuscript; and A.J.F., S.R.L., and B.C.W.T. approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Anita Vasavada and Hannah Pulcastro for their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This research was supported by a Beginning Grant in Aide (14BGIA20380385) from the Western States Affiliate of the American Heart Association (to B.C.W.T.), a New-Faculty Seed Grant from the Washington State University (to B.C.W.T.), and a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship from the College of Veterinary Medicine (to S.R.L.).

Editor: David Warshaw.

References

- 1.Gordon A.M., Huxley A.F., Julian F.J. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1966;184:170–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konhilas J.P., Irving T.C., de Tombe P.P. Frank-Starling law of the heart and the cellular mechanisms of length-dependent activation. Pflugers Arch. 2002;445:305–310. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0902-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Tombe P.P., Mateja R.D., Irving T.C. Myofilament length dependent activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;48:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald K.S., Wolff M.R., Moss R.L. Sarcomere length dependence of the rate of tension redevelopment and submaximal tension in rat and rabbit skinned skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1997;501:607–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.607bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang G., Ding W., Kawai M. Does thin filament compliance diminish the cross-bridge kinetics? A study in rabbit psoas fibers. Biophys. J. 1999;76:978–984. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77261-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y., Kawai M. The effect of the lattice spacing change on cross-bridge kinetics in chemically skinned rabbit psoas muscle fibers. II. Elementary steps affected by the spacing change. Biophys. J. 1993;64:197–210. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81357-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krasner B., Maughan D. The relationship between ATP hydrolysis and active force in compressed and swollen skinned muscle fibers of the rabbit. Pflugers Arch. 1984;400:160–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00585033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner B.C.W., Farman G.P., Miller M.S. Thick-to-thin filament surface distance modulates cross-bridge kinetics in Drosophila flight muscle. Biophys. J. 2012;103:1275–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawai M., Schulman M.I. Crossbridge kinetics in chemically skinned rabbit psoas fibres when the actin-myosin lattice spacing is altered by dextran T-500. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1985;6:313–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00713172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott G.F., Matsubara I. The constant-volume behaviour of the myofilament lattice in frog skeletal muscle: studies on skinned and intact single fibres by x-ray and light diffraction. J. Physiol. 1972;226:88P–89P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millman B.M. The filament lattice of striated muscle. Physiol. Rev. 1998;78:359–391. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godt R.E., Maughan D.W. Swelling of skinned muscle fibers of the frog. Experimental observations. Biophys. J. 1977;19:103–116. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(77)85573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godt R.E., Maughan D.W. Influence of osmotic compression on calcium activation and tension in skinned muscle fibers of the rabbit. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:334–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00581519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawai M., Zhao Y. Cross-bridge scheme and force per cross-bridge state in skinned rabbit psoas muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 1993;65:638–651. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81109-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konhilas J.P., Irving T.C., de Tombe P.P. Length-dependent activation in three striated muscle types of the rat. J. Physiol. 2002;544:225–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soukup T., Zacharová G., Smerdu V. Fibre type composition of soleus and extensor digitorum longus muscles in normal female inbred Lewis rats. Acta Histochem. 2002;104:399–405. doi: 10.1078/0065-1281-00660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Close R.I. Dynamic properties of mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol. Rev. 1972;52:129–197. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1972.52.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkholder T.J., Lieber R.L. Sarcomere length operating range of vertebrate muscles during movement. J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204:1529–1536. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.9.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner B.C.W., Wang Y., Palmer B.M. Measuring myosin cross-bridge attachment time in activated muscle fibers using stochastic vs. sinusoidal length perturbation analysis. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011;110:1101–1108. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00800.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godt R.E., Lindley B.D. Influence of temperature upon contractile activation and isometric force production in mechanically skinned muscle fibers of the frog. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982;80:279–297. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanner B.C.W., Breithaupt J.J., Awinda P.O. Myosin MgADP release rate decreases at longer sarcomere length to prolong myosin attachment time in skinned rat myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015;309:H2087–H2097. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00555.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulieri L.A., Barnes W., Maughan D.W. Alterations of myocardial dynamic stiffness implicating abnormal crossbridge function in human mitral regurgitation heart failure. Circ. Res. 2002;90:66–72. doi: 10.1161/hh0102.103221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer B.M., Schmitt J.P., Maughan D.W. Elevated rates of force development and MgATP binding in F764L and S532P myosin mutations causing dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013;57:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell K.B., Chandra M., Hunter W.C. Interpreting cardiac muscle force-length dynamics using a novel functional model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;286:H1535–H1545. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01029.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawai M., Halvorson H.R. Two step mechanism of phosphate release and the mechanism of force generation in chemically skinned fibers of rabbit psoas muscle. Biophys. J. 1991;59:329–342. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82227-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer B.M., Suzuki T., Maughan D.W. Two-state model of acto-myosin attachment-detachment predicts C-process of sinusoidal analysis. Biophys. J. 2007;93:760–769. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lymn R.W., Taylor E.W. Mechanism of adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis by actomyosin. Biochemistry. 1971;10:4617–4624. doi: 10.1021/bi00801a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyska M.J., Warshaw D.M. The myosin power stroke. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2002;51:1–15. doi: 10.1002/cm.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y., Tanner B.C.W., Palmer B.M. Cardiac myosin isoforms exhibit differential rates of MgADP release and MgATP binding detected by myocardial viscoelasticity. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013;54:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephenson D.G., Williams D.A. Effects of sarcomere length on the force-pCa relation in fast- and slow-twitch skinned muscle fibres from the rat. J. Physiol. 1982;333:637–653. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Capitanio M., Canepari M., Bottinelli R. Two independent mechanical events in the interaction cycle of skeletal muscle myosin with actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:87–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506830102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmiter K.A., Tyska M.J., Warshaw D.M. Kinetic differences at the single molecule level account for the functional diversity of rabbit cardiac myosin isoforms. J. Physiol. 1999;519:669–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0669n.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kad N.M., Patlak J.B., Warshaw D.M. Mutation of a conserved glycine in the SH1-SH2 helix affects the load-dependent kinetics of myosin. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1623–1631. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith D.A., Geeves M.A. Strain-dependent cross-bridge cycle for muscle. Biophys. J. 1995;69:524–537. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79926-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siemankowski R.F., Wiseman M.O., White H.D. ADP dissociation from actomyosin subfragment 1 is sufficiently slow to limit the unloaded shortening velocity in vertebrate muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:658–662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nyitrai M., Geeves M.A. Adenosine diphosphate and strain sensitivity in myosin motors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:1867–1877. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang G., Kawai M. Effect of temperature on elementary steps of the cross-bridge cycle in rabbit soleus slow-twitch muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2001;531:219–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0219j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G., Kawai M. Effects of MgATP and MgADP on the cross-bridge kinetics of rabbit soleus slow-twitch muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 1996;71:1450–1461. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iorga B., Adamek N., Geeves M.A. The slow skeletal muscle isoform of myosin shows kinetic features common to smooth and non-muscle myosins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3559–3570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bloemink M.J., Adamek N., Geeves M.A. Kinetic analysis of the slow skeletal myosin MHC-1 isoform from bovine masseter muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:1184–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bagni M.A., Cecchi G., Ashley C.C. Lattice spacing changes accompanying isometric tension development in intact single muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 1994;67:1965–1975. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80679-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huxley H.E. Recent x-ray diffraction and electron microscope studies of striated muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 1967;50(Suppl):71–83. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.6.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yagi N., Okuyama H., Kajiya F. Sarcomere-length dependence of lattice volume and radial mass transfer of myosin cross-bridges in rat papillary muscle. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1243-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brenner B., Yu L.C. Structural changes in the actomyosin cross-bridges associated with force generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:5252–5256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rome E. X-ray diffraction studies of the filament lattice of striated muscle in various bathing media. J. Mol. Biol. 1968;37:331–344. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams C.D., Regnier M., Daniel T.L. Axial and radial forces of cross-bridges depend on lattice spacing. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1001018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams C.D., Regnier M., Daniel T.L. Elastic energy storage and radial forces in the myofilament lattice depend on sarcomere length. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDonald K.S., Moss R.L. Osmotic compression of single cardiac myocytes eliminates the reduction in Ca2+ sensitivity of tension at short sarcomere length. Circ. Res. 1995;77:199–205. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee E.-J., Nedrud J., Granzier H.L. Calcium sensitivity and myofilament lattice structure in titin N2B KO mice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013;535:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farman G.P., Walker J.S., Irving T.C. Impact of osmotic compression on sarcomere structure and myofilament calcium sensitivity of isolated rat myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;291:H1847–H1855. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01237.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobacman L.S. Thin filament-mediated regulation of cardiac contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1996;58:447–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith D.A., Geeves M.A. Cooperative regulation of myosin-actin interactions by a continuous flexible chain II: actin-tropomyosin-troponin and regulation by calcium. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3168–3180. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Linari M., Brunello E., Irving M. Force generation by skeletal muscle is controlled by mechanosensing in myosin filaments. Nature. 2015;528:276–279. doi: 10.1038/nature15727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kampourakis T., Sun Y.-B., Irving M. Myosin light chain phosphorylation enhances contraction of heart muscle via structural changes in both thick and thin filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E3039–E3047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602776113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berchtold M.W., Brinkmeier H., Müntener M. Calcium ion in skeletal muscle: its crucial role for muscle function, plasticity, and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:1215–1265. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horowits R., Podolsky R.J. The positional stability of thick filaments in activated skeletal muscle depends on sarcomere length: evidence for the role of titin filaments. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:2217–2223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ait-Mou Y., Hsu K., de Tombe P.P. Titin strain contributes to the Frank-Starling law of the heart by structural rearrangements of both thin- and thick-filament proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:2306–2311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516732113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farman G.P., Gore D., de Tombe P.P. Myosin head orientation: a structural determinant for the Frank-Starling relationship. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;300:H2155–H2160. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01221.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perz-Edwards R.J., Irving T.C., Reedy M.K. X-ray diffraction evidence for myosin-troponin connections and tropomyosin movement during stretch activation of insect flight muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:120–125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014599107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huxley H.E., Stewart A., Irving T. X-ray diffraction measurements of the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments in contracting muscle. Biophys. J. 1994;67:2411–2421. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80728-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wakabayashi K., Sugimoto Y., Amemiya Y. X-ray diffraction evidence for the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments during muscle contraction. Biophys. J. 1994;67:2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80729-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greenberg M.J., Shuman H., Ostap E.M. Inherent force-dependent properties of β-cardiac myosin contribute to the force-velocity relationship of cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 2014;107:L41–L44. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]