Abstract

Low and middle income countries (LMICs) bear a huge, disproportionate and growing burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) which constitutes a threat to development. Efforts to tackle the global burden of CVD must therefore emphasise effective control in LMICs by addressing the challenge of scarce resources and lack of pragmatic guidelines for CVD prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. To address these gaps, in this analysis article, we present an implementation cycle for developing, contextualising, communicating and evaluating CVD recommendations for LMICs. This includes a translatability scale to rank the potential ease of implementing recommendations, prescriptions for engaging stakeholders in implementing the recommendations (stakeholders such as providers and physicians, patients and the populace, policymakers and payers) and strategies for enhancing feedback. This approach can help LMICs combat CVD despite limited resources, and can stimulate new implementation science hypotheses, research, evidence and impact.

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

Low and middle income countries (LMICs) face a disproportionately heavy burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with scarce resources and lack of pragmatic guidelines.

Owing to the relative paucity of locally conducted research, care providers in LMICs seeking to practice evidence-based medicine often attempt to directly incorporate available practice guidelines imported from HICs.

What are the new findings?

We present a novel implementation cycle for developing, contextualising, communicating and evaluating concise expert consensus CVD solutions for LMICs.

We propose a translatability scale to grade expected ease of implementation of practice points and recommendations especially in resource-limited settings.

Recommendations for policy

The proposed implementation cycle can help LMICs combat CVD despite limited resources.

Targeted stakeholders (players) should include providers and physicians, patients and the populace, policymakers and payers as well as implementation partners.

These ideas can stimulate new CVD implementation science hypotheses, research, evidence and global impact.

Introduction

The world is facing an enormous health disparity.1 2 The largest burden of non-communicable diseases especially cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), which constitute the leading cause of death and disability in the world (accounting for 60% of global deaths), is borne by low and middle income countries (LMICs).1 2 Unlike high income countries (HICs), LMICs lack the resources and pragmatic solutions to tackle this crippling yet increasing burden.1 2 In this article, we proffer a novel implementation cycle for identifying and implementing effective solutions to combat the rising CVD burden in the low-resource settings of LMICs, by placing proof in pragmatism.

The growing global disparity in cardiovascular health

Any attempt to successfully tackle the global burden of CVD must emphasise its effective control in LMICs where it is a threat to development.1 2 However, although up to 90% of the worldwide CVD burden is borne by LMICs, they have only about 10% of the research capacity and healthcare resources necessary to investigate and identify sustainable solutions to address this escalating challenge.1–4

Moreover, proven therapies and strategies for controlling CVD developed in HICs may not necessarily be pragmatic for LMICs if not adapted.3 Owing to the relative paucity of locally conducted research, care providers in LMICs seeking to practice evidence-based medicine often attempt to directly incorporate available practice guidelines imported from HICs, even though the settings, patients and resources are vastly different (tables 1–3).3 5–7 In particular, geopolitical and socioeconomic problems in most LMICs present barriers to optimal CVD control. These include low population health literacy, limited health budgets, corruption, uncoordinated health systems, unstable political climate, faulty policies, negative influence of certain food industries and tobacco companies, lack of appropriate infrastructure, deficient pharmaceutical supply chains, predominant out-of-pocket health expenditures and barely existent health insurance systems.3 5–9

Table 1.

Metaphor of the ‘car’ and ‘bridge’—thrombolysis in acute stroke17 in LMICs setting*

| Stakeholders | Expected roles |

|---|---|

| Populace | General awareness about stroke to enable immediate recognition of stroke and initiation of appropriate actions. |

| Patient | The patient/caregiver/neighbour/coworker need to be able to recognise stroke immediately when it occurs and act fast by organising/initiating rapid transfer to a centre where urgent investigations and thrombolytic therapy can be delivered. |

| Providers | Doctors/neurologists need to be competent to rapidly investigate, decide on eligibility, administer and monitor thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Pharmacist: To ensure availability of potent thrombolytic therapy (from a genuine source, not expired, appropriately stored and dispensed). |

| Policymakers | To make policies that will ensure (a) community level sensitisation about stroke recognition and rapid action, (b) rapid evacuation services for patients who suffered a stroke within the therapeutic time window and (c) availability of proximal certified centres for rapid evaluation and administration of thrombolytic therapies. |

| Payers | Health insurance companies, the government, drug companies to work together using the antiretroviral therapy model to ensure accessibility of thrombolytic therapy to LMICs using a combination of different mechanisms: discounts, subsidies, supplementation, local manufacture of generic products and donations. |

| Partners | To ensure synergistic engagement of all stakeholders listed above to ascertain, evaluate and monitor implementation. |

*Stroke, the clinical culmination of various cardiovascular risk factors, is the leading cause of cardiovascular death, disability and dementia in LMICs. It often presents in a dramatic acute/hyperacute manner and requires urgent and appropriate action to be taken by all stakeholders. Thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke is a level A class I recommendation which is proven in HICs.10 While awaiting possible pharmacogenomic drug trials and other new contextual evidence in LMICs, this current evidence may be applied. The ‘car’ is the recommendation ie ‘to administer thrombolytic therapy to all eligible patients with ischemic stroke within the therapeutic time window’. Sections of the bridge are the roles to be played by stakeholders without which the bridge will be impassable and the service cannot be delivered.

HICs, high income countries; LMICs, low and middle income countries.

Table 2.

Action should involve all stakeholders (sections of ‘the bridge’)

| Stakeholders | Examples of actions and roles required to control CVD |

|---|---|

| Patients | Evidence-based cardiovascular health information/tips, educational materials, self-efficacy tools to be made available through novel multiple friendly channels to patients to enable them take, seek and evaluate appropriate preventive, therapeutic and restorative actions. |

| Providers | High-level translatable customised recommendations to be made available/accessible to clinicians, physicians, pharmacists and other medical and paramedical personnel in LMICs using multipronged novel-friendly channels. Development of task-redistribution approaches. Training and capacity building. This will enable them to be aware of and implement such recommendations in eligible patients. |

| Populace | Using several novel channels, media, forums and community resources to engage the entire general populace across the lifespan about the burden, prevention and other interventions for the entire spectrum of CVDs (Cardiovascular Cascade) from ideal cardiovascular health to cardiovascular death. This includes population level screening for CVD and CVD risk factors and awareness campaigns in communities, schools, workplaces, places of worship, webspace, etc. This will enable them take, seek and evaluate appropriate preventive, therapeutic and restorative actions. |

| Policymakers | Collection and synthesis of the best available global and local evidence to produce evidence briefs for policy as the primary input into structured deliberate dialogues with the policymakers. Engagement of all layers/grades of policymakers using novel channels. This will enable them to provide relevant infrastructure, medications, facilities and equipment, develop evidence-based translatable policies and performance indicators and formulate policy networks and peer-review mechanisms for policy implementation. |

| Payers | Engagement of payers to support the implementation of high-level recommendations with relevant resources. Discounts, subsidies, supplementation, local manufacture of generic products and donations could improve access to medications and devices. |

| Partners | No single organisation can combat the CVD epidemic alone. It is inevitable to establish and nurture a broad-based synergistic system of collaborations among the implementation partners including:

|

CAMS, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences; CIHR, Canadian Institutes of Health Research; COUNCIL, COntrol UNique to Cardiovascular diseases In LMICs; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GACD, Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases; ICMR, Indian Council of Medical Research; INCMNSZ, National Institute of Medical Science and Nutrition Salvador Zubiran; LMICs, low and middle income countries; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NICE, National Institute for health and Care Excellence. NCD-RiSC, Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factor Collaboration; NCDs, Non-Communicable Diseases; NEPAD, The New Partnership for Africa's Development; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Table 3.

Evidence for the missing links in existing cardiovascular diseases guidelines for low and middle income countries: the diabetes mellitus scenario from three continents

| Country/region | Malaysia/Asia | Brazil/South America | South Africa/Africa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication details | |||

| Year | 2015 | 2010 | 2012 |

| Title | Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (5th edition)6 | Algorithm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a position statement of Brazilian Diabetes Society5 | The 2012 SEMDSA guideline for the management of type 2 diabetes (revised)7 |

| Authors | Ministry of Health, Malaysia | Lerario AC, et al | SEMDSA |

| Basis of recommendation | Modified from Scottish Intercollegiate guidelines network, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, local practice considerations | International literature, ADA/EASD algorithm. Joslin Diabetes Center | Update literature and the Department of Health's draft type 2 diabetes guideline document. |

| Specialties of the members of task force | Endocrinologists Family medicine specialists General physicians. Paediatric endocrinologists Public health physicians. Dieticians |

NS | Endocrinologists Family Practitioners Diabetes Educators Department of Health representatives. Medical Council representatives |

| Methods in detail | Members of the task force were assigned topics. Articles retrieved were graded. Draft guideline was posted on the Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society, Ministry of Health Malaysia websites for comment and feedback. Guideline presented to the Technical Advisory Committee and the Health Technology Assessment and Clinical Practice Guidelines Council, Ministry of Health for review and approval. |

Brazilian Diabetes Society obtained opinions of a panel of renowned Brazilian specialist about recommendations and controversial arguments on the treatment of T2DM in international literature. Arguments were presented to the panel with each member scoring each argument on a Likert scale. |

Broad topic of management was divided into smaller sections and allocated to experts to lead. Information on each section was presented to the general committee and amendments and additions suggested best on ‘best practice’. |

| Clinical issues addressed (components of the cardiovascular quadrangle) | |||

| Primordial prevention | No | No | Yes |

| Pre-diabetes | No | No | No |

| Age-specific treatment | No | No | Yes |

| Nutrition | Yes | No | Yes |

| Exercise | Yes | No | Yes |

| Acute care/emergencies | Yes | No | Yes |

| Conventional care | Yes | No | No |

| Rehabilitation | No | No | No |

| Target population (the 6Ps) | |||

| Physicians | Yes | NS | Yes |

| Nurses | Yes | NS | Yes |

| Primary caregivers | Yes | NS | Yes |

| Pharmacist | Yes | NS | No |

| Dieticians | Yes | NS | Yes |

| Policymakers | No | NS | Yes |

| Payers | No | NS | Yes |

| Paramedics | No | NS | No |

| Patients and populace | No | NS | No |

| Implementation partners | No | No | No |

| Other considerations (including translatability and ELSE) | |||

| Translatability rating | No | No | No |

| Ethical | No | No | No |

| Legal | No | No | No |

| Social | Yes | No | No |

| Psychological | Yes | No | No |

| Economic | No | No | No |

| Comorbidity | Yes | No | Yes |

| Quality indicator | Yes | Yes | No |

| Dissemination channels | No | No | No |

| Surveillance | No | No | No |

| Renewal date | 2019 | NS | NS |

ADA, American Diabetes Association; EASD, European Association for the Study of Diabetes; ELSE, ethical, legal, sociocultural and economic; NS, not stated; SEMDSA, Society for Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes of South Africa; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Therefore, despite existing high-level evidence-based guidelines from HICs and clear evidence of a declining CVD burden in HICs,1 2 4 8 the CVD burden continues to escalate among LMICs.1 2 4 8 The ongoing ‘parallel CVD universes’ is akin to the situation in global polio prevention efforts where despite the discovery of the polio vaccine over half a century ago, new cases are still occurring in LMICs.10 Within the socioeconomic reality in LMICs, contextually appropriate recommendations for CVD control need to be developed.8 9 11 12

Ideally, new direct evidence about the effectiveness of CVD interventions in LMICs settings should be generated, but currently, LMICs do not have the wherewithal to support CVD implementation science initiatives.3 4 Also, there are insufficient resources from HICs to support CVD research in LMICs in a widespread and long-term manner.3 4 13 Since the aforementioned potential strategies to ameliorate the CVD burden in LMICs will be either partial or long term, and presently lives are being lost and futures blighted, intervening action is warranted in the mean time.3 4 13

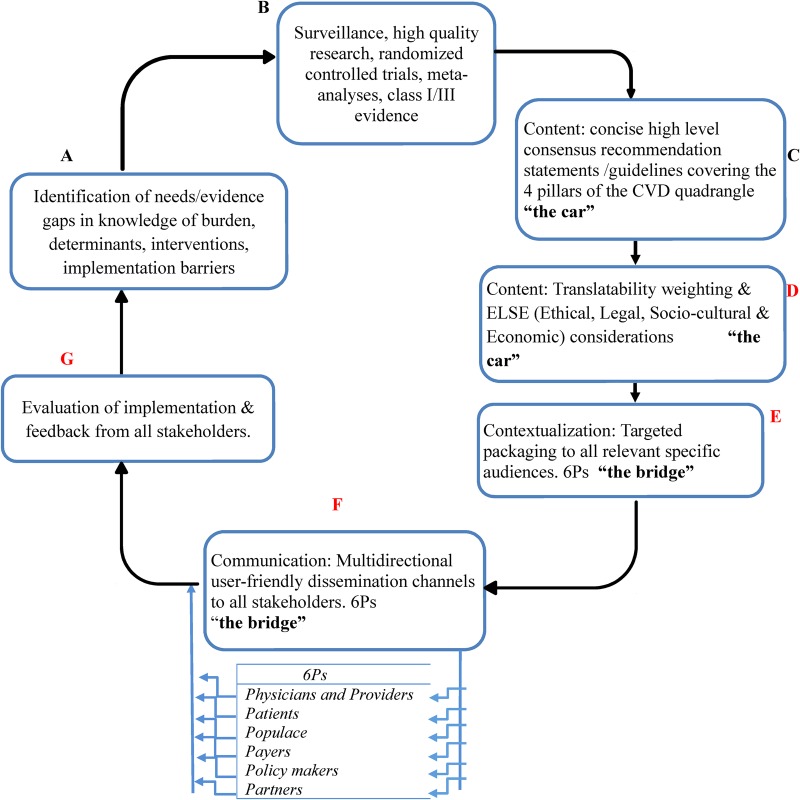

Systematic approaches are urgently needed to translate the existing high-level evidence obtained in HICs into pragmatic strategies to reduce the escalating burden of CVD in LMICs, while gradually creating an implementation pipeline to stimulate, absorb, process, and disseminate new direct evidence as they accrue from LMICs in future. This should include a new approach to the content, packaging and delivery of evidence-based recommendations to make them more accessible, contextual, and actionable, across the CVD-care continuum, involving all stakeholders, while avoiding disease siloes, in LMICs where the burden is heaviest (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pragmatic guideline development and implementation cycle. Points D–G are often neglected in existing guidelines. Low and middle income countries (LMICs)-specific cardiovascular disease (CVD) expert consensus guidelines that incorporate available strictly high-level scientific evidence along with pragmatic recommendations for how to implement these proven therapies using contextually relevant methods in LMICs, and effectively communicated via the already widely available interactive channels (like mobile phones) to all stakeholders, could do away with the multilevel barriers and go a long way in stemming the rising CVD burden in LMICs.

Translating the content of evidence-based recommendations

First, there is a need to unravel the major gaps and needs for interventions to control CVD in LMICs along the entire cardiovascular cascade: from ideal cardiovascular health, through emergence of CVD risk factors, to symptomatic CVD culminating in disability and death.4 This should cover the entire intervention spectrum as proposed in the cardiovascular disease quadrangle4 (epidemiological surveillance and research networks including establishment of research agenda and priorities; primordial, primary and secondary prevention across the lifespan; hyperacute and acute care; and, rehabilitation and reintegration) (see figure 1, points (A–C).4

Next, CVD practice guidelines for LMICs could be developed (or enhanced where already available) using solutions from the corresponding successful HIC guidelines which can be adapted to LMICs healthcare peculiarities. The focus should strictly be on high-level recommendations (ie, class I or III evidence with level A recommendations only) for the selected CVD entities.3 9 11 12 However, to develop such sustainable solutions, the multilevel barriers and facilitators of implementing CVD guidelines in LMICs need to be fully understood.3 9 11 12 Examples of such barriers include socioeconomic and ecological conditions as well as societal upheavals which influenced the sustainment of interventions in sub-Saharan Africa.3 9 11 12 Thus, gaps and barriers in the implementation pipeline including lack of relevant facilities, devices, medications and personnel should be taken into account while adapting the high-level content.3 9 11 12

The complexity and nature of these barriers vary for different interventions.3 9 11 12 While some interventions can be implemented at home by the individual without the need for sophisticated equipment, highly skilled medical personnel, advanced medical infrastructures or new legislations, others would require all of these for implementation. Therefore, in addition to ranking solutions according to classes of evidence and levels of recommendation, it is crucial to grade them in descending order of translatability (figure 1, point (D)). A translatability scale for grading solutions according to the nature and relative complexities of barriers that need to be navigated for their successful implementation is proposed below. The proposed scale could be modified iteratively to make it more reproducible once adopted and in use as practical issues arise regarding its applications and implications.

Ta: Interventions that are neither limited by cost nor personnel. In most cases they can be implemented by individuals on their own with little or no need for highly skilled personnel, medications, expensive appliances or sophisticated infrastructure (eg, increased physical activity,14 dietary salt reduction,15 healthy dietary choices).

Tb: Interventions limited mainly by cost/availability/affordability only with little or no need for intense continuous care or supervision by highly skilled personnel (eg, medications8 9 that can be administered once correctly prescribed and safe for the individual patient eg, oral antiplatelet to prevent stroke).

Tc: Interventions limited mainly by the absence of expert personnel and facility only but not cost (eg, speech therapy:16 when the potential beneficiaries are able to afford but not access the service due to the absence of speech therapist and/or gadgets required for same).

Td: Interventions limited by both personnel, and cost (eg, thrombolytic therapy17 table 1).

While determining translatability, ethical, legal, sociocultural and economic (ELSE) factors should be considered (figure 1, point D) in addition to other barriers and facilitators. Just telling an individual patient to reduce alcohol use may be difficult although cheap. However, if the guidelines consider the sociocultural uniqueness of the country, then allocation can be made for family or religious input. Use of translatability weighting gives every healthcare provider a recommendation to work with irrespective of their cadre. There is nothing to be gained in forcing the latest thrombolytic therapy down the throats of a health extension worker in an African village when he/she is never going to be able to get it done. Why not just ensure that they at least follow proven Ta practices for CVD prevention and treatment?

However, while Ta preventive interventions such as increasing physical activity and modifying diet are highly cost-effective ultimately, implementing them at scale in a population may require significant expenditure initially. Their implementation may also be hindered by difficulty in changing entrenched behaviours at the individual and population levels particularly as they may require changing norms to prevent an invisible problem without immediately obvious benefits. For instance, individuals may not immediately realise that unhealthy diet and sedentary lifestyle can lead to atherosclerosis, stroke and premature death. So the challenge is in making the consequences of sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy diet obvious and communicating the effectiveness and basis of the required change at the population and personal level. This may include funding of mass educational programmes needed to motivate change and provision of an enabling environment to make the change possible and sustainable. Social capital can be provided through family and social activities such as ‘walk for life’ exercise programmes integrated into the routine activities by community, professional and religious groups.

Nevertheless, adopting the translatability scale can encourage the discovery, development, prioritisation and adoption of highly effective adaptable Ta recommendations which can perhaps be more easily implemented by all stakeholders in LMICs. It can also promote implementation science research for the modification of barriers and facilitators for the translation of Td recommendations in order to elevate them towards Ta status.

The implementation of complex interventions in primary care is influenced by the evidence of benefit, ease of use and adaptation to local circumstances.12 Identifying and overcoming the causes of the evidence-to-practice gap and improving the translatability and ‘fit’ between intervention and context is critical in determining the success of implementation.12 The current scenario presents a unique opportunity to develop and implement Ta solutions and recommendations in LMICs. In addition, implementing such high level Ta recommendations in LMICs can provide insights for implementation in HICs. These considerations can inform the development of pragmatically weighted recommendations in the form of guidelines, practice points, statements, health tips and messages on CVD which are packaged and tailored to all specific audiences (tables 1 and 2).

Examining existing LMICs CVD guidelines through the lens of the implementation cycle reveals gaps in their development and content (figure 1, points (A–D)). This is illustrated by three type 2 diabetes mellitus guidelines from LMICs in three continents5–7 (table 3). Apart from weaknesses in the content (such as lack of adequate and systematic considerations of translatability, ethical, legal, socioeconomic implications), appropriate user-friendly dissemination channels to target audiences were not clearly articulated.5–7

Engaging stakeholders in the delivery of recommendations

Bulky consensus guidelines published by many professional bodies in academic journals to increase healthcare providers' awareness of evidence-based approaches to disease management have often neither percolated down to the stakeholders nor produced the desired results.18 Dissemination of high-level CVD recommendations in LMICs, therefore, must be transformed and combined with effective implementation strategies to drastically improve the knowledge, attitude, behaviour and practice of all stakeholders and foster an enabling implementation environment so as to produce and sustain the desired effects (tables 1 and 2).

Hitherto, attention has been focused solely on ‘the car’ (the evidence-based recommendation) to the exclusion of ‘the bridge’ (the stakeholders) over which the car must ply in order to deliver the care and desired outcomes (figure 1 and table 1).17 For example, the timely delivery of thrombolytic therapy to eligible patients who suffered a stroke17 requires the coordinated actions of all stakeholders including the patient, caregiver and all other players in the health sector.19 Therefore, in LMICs, there is a need for contextualisation (targeted packaging) of solutions and their dissemination through novel cost-effective multidirectional interactive channels to mobilise every stakeholder so as to foster ownership by all. This is in line with the recognition of community ownership and mobilisation as crucial facilitators for intervention sustainability, both early on and after intervention implementation by many of the 41 studies (1996–2015) in a systematic review of empirical literature to explore how health interventions implemented in sub-Saharan Africa are sustained.9 These findings further support the recommendation of contextualisation and targeted packaging of solutions to all relevant specific audiences in the implementation cycle.12 Considerations for contextualisation should include factors related to each of the 6Ps (tables 1 and 2 and figure 1) including external contextual factors (policies, incentivisation structures, dominant paradigms, stakeholders' buy-in, infrastructure and advances in technology), organisation-related factors (culture, available resources, integration with existing processes, relationships, skill mix and staff involvement) and individual professional factors (professional role, underlying philosophy of care and competencies).12

Apart from gaps in contextualisation, the communication of solutions to targeted audiences through appropriate channels is often deficient (figure 1, point (F)).20 For instance, in a survey of 485 UK-based principal investigators of publicly funded applied and public health research, less than one-third stated that they would produce key messages for specific audiences.20 This is despite the fact that most respondents indicated that part of their dissemination plan involved targeting specific audiences (such as policymakers, service managers or general practitioners).20 Although researchers recognise the importance of disseminating the findings of their work, they are focused on academic publications and the few who apply a range of dissemination channels do so in an uncoordinated fashion.20

This critical communication gap must be addressed comprehensively. Therefore, although it is not clear which channels work best,20 we propose communication cycles and circles to disseminate targeted key messages through multiple channels including social media, text messaging platforms, mobile phone apps, applied theatre arts, websites, mobile health platforms, electronic media, print media, dedicated forums and monitoring software/dashboards. This will enable researchers to interactively and continuously engage with all stakeholders; such as providers (personnel–clinicians, healthcare workers), policymakers, patients, populace (communities), partners and payers (table 2 and figure 1, points (E and F)).9 20 The right combinations of channels can be selected based on the preferences of the target audiences and accruing evidence.

Enhancing feedback by harmonising outcome measures

The effectiveness of the entire implementation process and dissemination channels should be evaluated using appropriate measures. Although it is known that implementation will greatly benefit from easy-to-apply, harmonised and rigorous outcome measures; reviews suggest that less than half of the existing measures are psychometrically validated (ie, in many cases, no data exists on whether the measure assesses the construct it is intended to address).21 Other challenges include the difficulties in applying such measures in routine clinical practice settings, and the dearth of measures available for certain implementation constructs (eg, context and adaptation).21 Furthermore, the use of different outcome measures by similar studies prevents the integration of results across such studies.21

It is therefore crucial for implementation partners (table 2 and figure 1) to develop and use simple and effective harmonised outcome measures and performance indicators to monitor and evaluate implementation progress along the four axes of the cardiovascular quadrangle. For example, reducing the burden of stroke will require the monitoring of stroke surveillance, prevention, acute care and rehabilitation services. Enhancing the quality of such feedback will facilitate the identification of evidence gaps and implementation barriers, which can in turn lead to new research studies (figure 1, points (A, B and G) and yield better evidence and recommendations.

This will potentially fast-track integrated knowledge translation driven by collaboration between researchers and decision-makers.22 Patients and service leaders can help researchers to clarify goals, gather new evidence in real-life complex systems, and identify appropriate approaches for conducting and evaluating planned changes.23 Such evaluations may be formative, using findings to optimise implementation, or summative, producing evidence of ultimate impact or both. In any case, careful thought is needed to protect the integrity of evaluations and feedback.23

Conclusion

Practice guidelines are developed based on the strength of available evidence.18 However, the reality is that most of the strong evidence stem from clinical trials which usually test ‘one thing at a time’, and not necessarily how complex systems operate.3 9 11 12 Ironically, although the recommendations are often published in high-impact visible journals, they are often poorly contextualised and communicated and so do not percolate down to key stakeholders,18 and their implementation remains a challenge, particularly in LMICs.13 18 We therefore propose an implementation cycle which addresses hitherto missing links in CVD solutions. It includes strategies for generating new evidence in real-life complex ecosystems and implementation environment, and processes for content development, contextualisation, communication and feedback (figure 1). This pathway can incrementally stimulate, monitor, absorb and process the accruing evidence from researchers and consortia examining CVDs in LMICs while motivating all stakeholders and creating enabling environment for the implementation of existing evidence-based solutions. Holistic deployment of this cycle, placing proof in pragmatism, can revolutionise our capacity to tame the burden of CVDs in LMICs despite limited resources.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: Follow Mayowa Owolabi at @mayowaoowolabi

Contributors: MO drafted the manuscript. All authors gave substantial contributions to the conception of the paper and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the paper for publication. MO is the guarantor.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (U54 HG007479) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U01 NS079179).

Competing interests: The authors are members of the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases—COntrol UNique to Cardiovascular diseases In LMICs—(GACD-COUNCIL) initiative. GACD is the first alliance of the world's biggest public research funding agencies, which currently is funding 15 hypertension and 16 diabetes implementation science projects in LMICs. MO is the pioneer chair of the H3Africa CVD research consortium, the largest in Africa with projected sample size of >55 000 participants. BO is a pre-eminent stroke physician with expertise in guideline development. JM has expertise in implementation science for CVDs in LMICs. The ideas presented here respond to the challenges of combatting CVDs in LMICs. MO and BO are supported by U01 NS079179 and U54 HG007479 from the National Institute of Health and the GACD.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The NCD Alliance. UN NCD facts: the global epidemic. NCD Alliance 2015. http://ncdalliance.org/globalepidemic

- 3.Miranda JJ, Zaman MJ. Exporting ‘failure’: why research from rich countries may not benefit the developing world. Rev Saude Publica 2010;44:185–9. 10.1590/S0034-89102010000100020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owolabi MO, Akarolo-Anthony S, Akinyemi R et al. The burden of stroke in Africa: a glance at the present and a glimpse into the future. Cardiovasc J Afr 2015;26:S27–38. 10.5830/CVJA-2015-038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerario AC, Chacra AR, Pimazoni-Netto A et al. Algorithm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a position statement of Brazilian Diabetes Society. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2010;2:35 10.1186/1758-5996-2-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health. Clinical practice guidelines: management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (5th Edition). Internet 2015. http://www.mems.my/file_dir/14963565685527d8749429c.pdf

- 7.SEMDSA. The 2012 SEMDSA guideline for the management of type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol Metab Diab S Afr 2016;17:S1–94. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/22201009.2012.10872277#.VvCQ-_krLDc [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Fuster V. Global burden of CVD: focus on secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol 2015;201(Suppl 1):S1–7. 10.1016/S0167-5273(15)31026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwelunmor J, Blackstone S, Veira D et al. Erratum to: ‘Toward the sustainability of health interventions implemented in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and conceptual framework’. Implement Sci 2016;11:53 10.1186/s13012-015-0367-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel M, Orenstein W. A world free of polio—the final steps. N Engl J Med 2016;374:501–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1514467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN et al. Achieving change in primary care—effectiveness of strategies for improving implementation of complex interventions: systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009993 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN et al. Achieving change in primary care-causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci 2016;11:40 10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owolabi MO, Bower JH, Ogunniyi A. Mapping Africa's way into prominence in the field of neurology. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1696–700. 10.1001/archneur.64.12.1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine—evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015;25(Suppl 3):1–72. 10.1111/sms.12581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisoli TM, Schmieder RE, Grodzicki T et al. Salt and hypertension: is salt dietary reduction worth the effort? Am J Med 2012;125:433–9. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dignam JK, Rodriguez AD, Copland DA. Evidence for intensive aphasia therapy: consideration of theories from neuroscience and cognitive psychology. PM R 2016;8:254–67. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44:870–947. 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–236. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jameson JL, Longo DL. Precision medicine—personalized, problematic, and promising. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2229–34. 10.1056/NEJMsb1503104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW et al. Does dissemination extend beyond publication: a survey of a cross section of public funded research in the UK. Implement Sci 2010;5:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabin BA, Lewis CC, Norton WE et al. Measurement resources for dissemination and implementation research in health. Implement Sci 2016;11:42 10.1186/s13012-016-0401-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A et al. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci 2016;11:38 10.1186/s13012-016-0399-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamont T, Barber N, de Pury J et al. New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ 2016;352:i154 10.1136/bmj.i154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]