Abstract

Beginning in December 2016, calorie labeling on menus will be mandatory for US chain restaurants and many other establishments that serve food, such as ice cream shops and movie theaters. But before the federal mandate kicks in, several large chain restaurants have begun to voluntarily display information about the calories in the items on their menus. This increased transparency may be associated with lower overall calorie content of offered items. This study used data for the period 2012–14 from the MenuStat project, a data set of menu items at sixty-six of the largest US restaurant chains. We compared differences in calorie counts of food items between restaurants that voluntarily implemented national menu labeling and those that did not. We found that the mean per item calorie content in all years was lower for restaurants that voluntarily posted information about calories (the differences were 139 calories in 2012, 136 in 2013, and 139 in 2014). New menu items introduced in 2013 and 2014 showed a similar pattern. Calorie labeling may have important effects on the food served in restaurants by compelling the introduction of lower-calorie items.

On November 25, 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the final rule for implementation of an Affordable Care Act provision that mandates calorie labeling on menus in chain restaurants.1 The rule requires that calorie information be posted on menus and menu boards in chain restaurants and similar retail food establishments with twenty or more locations nationwide. The final regulations expanded the proposed rule to include nearly all food establishments, including quick-service and table-service restaurants, grocery stores and superstores, movie theaters, bowling alleys, amusement parks, ice cream shops, and takeout and delivery establishments. The rule will be implemented beginning in December 2016.

Policy makers conceptualized menu labeling as a tool to give consumers better information about their food purchases and to help decrease the typically high calorie content of restaurant meals.2 Yet rigorous evaluations of existing state and local menu labeling efforts with control groups and in real-world settings generally have shown either small or no impact on consumer calorie purchases.3–6

Instead of directly changing consumer behavior, menu labeling could encourage restaurants to reformulate current offerings or develop products with fewer calories, leading to lowered calorie consumption by customers. One study found that calories in chain restaurant menu items declined in King County, Washington,7 after the county enacted a local labeling requirement for chain restaurants.8 Another study demonstrated that the calories in newly introduced menu items at large chain restaurants declined by an average of sixty calories per item (a 12 percent decline) from 2012 to 2013, although very few of these chains voluntarily introduced labeling.9

Anticipating federal mandatory menu labeling requirements, several large chain restaurants voluntarily began adding calorie labeling to their menus.10,11 We compared the differences between calorie counts in large national chain restaurants that voluntarily implemented labeling of caloric content on their menus to calorie counts at those restaurants that did not. To our knowledge, this is the first study to make such comparisons.

Study Data And Methods

DATA

We used data from the MenuStat project, which is a census of menu items in most of the 200 largest US restaurant chains. Information about the data set’s collection methods is available elsewhere.12 Briefly, data collection began in 2012 with 66 of the 100 largest US restaurant chains (based on US sales) and has expanded annually. The data include caloric content and other information about menu items from restaurant websites. For the present study, we included data for the 66 restaurant chains that contributed data to MenuStat for all three years available thus far, 2012–14.

Based on telephone conversations or e-mail correspondence with representatives of each of the sixty-six restaurant chains, information from news stories and restaurant press releases, and visits to a convenience sample of restaurant venues in the Baltimore, Maryland, and Boston, Massachusetts, areas, we determined that five of the sixty-six chains had introduced voluntary calorie labeling nationally before 2014: Chick-fil-A in 2013, Jamba Juice in 2010, McDonald’s in 2012, Panera in 2010, and Starbucks in 2013.

We analyzed all 23,066 menu items in the sixty-six restaurant chains for which there were data for 2012–14. Because we were able to analyze a census of all items on the menus during the study period, the patterns we observed in that time period are true in those restaurants. However, to make inferences on the national level, we considered the data to be a nonprobability sample of menu items from other large US-based restaurant chains.

We also combined information from AggData (https://www.aggdata.com/) with information on local menu labeling laws compiled by the Center for Science in the Public Interest to identify, for each restaurant chain, the proportion of locations in a county with a local law requiring menu labeling.8 AggData provides the location of each chain restaurant outlet in the United States, including outlets for all sixty-six chains included in the MenuStat database.12 The data are highly accurate. Previous research has typically used data from Info USA or Dun and Bradstreet to identify food outlet locations, but the accuracy of information in these sources ranges from approximately 50 percent to 80 percent, and there is some evidence that accuracy varies according to neighborhood characteristics such as median household income.13,14

ANALYSIS

We examined three continuous outcomes for the sixty-six restaurant chains: per item mean calories for the full menu, for each year in the period 2012–14; per item mean calories for each year in the period among items on the menu in all three years; and per item mean calories in newly introduced menu items in 2013 and 2014, compared to items on the menu in 2012 only. We examined each of these outcomes separately, comparing restaurant chains with voluntary menu labeling to those without such labeling. We also compared the third outcome in specific chains with voluntary labeling to that outcome in their direct competitors (defined below).

We defined menu items offered in all three years as those items with the same item name and description within a given restaurant and menu category for each of the three years. New menu items were defined as those that had no item name, description, or calories recorded in one year but that did have that information recorded in the following year.

For the first and second outcomes (per item calorie content by year), we included an indicator variable for the years 2013 or 2014, with parameter estimates that reflected differences from 2012 to each subsequent year. For the third outcome (difference in calories between newly introduced items compared to older items), we included an indicator of whether a menu item was newly introduced in 2013 or 2014, compared to the reference value of being on the menu in 2012 only. For all outcomes, the main independent variable was the interaction between these respective year indicators and voluntary menu labeling status.

As mentioned above, for each of the chains with voluntary menu labeling we identified direct competitors for purposes of comparison. Jamba Juice was excluded from this analysis because there was no direct competitor in the database.

For Chick-fil-A and McDonald’s, we identified competitors as other chain restaurants with a similar focus on a specific menu category (chicken or hamburgers). Two of the authors coded competitors based on the dominant menu offerings (for example, McDonald’s was coded as a hamburger chain and Chick-fil-A was coded as a chicken chain). A third author was available to adjudicate any differences, but there were none. For Panera and Starbucks, we identified competitors based on restaurant focus—that is, they were compared to all other fast casual restaurants.

We compared Panera and Starbucks together with all other fast casual and coffee restaurants in the database. We combined Panera and Star-bucks because of the small number of menu items overall and the small number of new menu items introduced in 2014 among these two groups of restaurants.

We identified five direct competitors for Chick-fil-A, twelve for McDonald’s, and eleven for Star-bucks and Panera combined. The menu category of focus and restaurant focus for each chain restaurant are available in the online Appendix Exhibit A1.15

Our analyses included covariates to classify menu items, including whether an item was offered on the children’s menu and whether an item was offered regionally or for a limited time only. At the restaurant level, we included covariates to indicate whether a restaurant was national or regional (that is, if it had locations in each of the nine US census divisions or not), and restaurant type (fast food, full service, or fast casual).

Menu labeling requirements had been enacted in more than twenty regions before the federal requirements.1,8 Therefore, we included a covariate to measure the proportion of locations of each restaurant chain that was subject to local labeling laws in 2012–14, and we categorized this continuous measure into tertiles. We used this covariate at the level of the county (instead of ZIP code or state) since most local menu labeling was implemented in cities and states, making the county the closest geographical match. Definitions of covariates and descriptive statistics of restaurant-level data are included in the Appendix, along with information about the MenuStat data set.15

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

The unit of analysis was each menu item. We employed generalized linear models to examine differences between menu items offered in chain restaurants with national voluntary menu labeling and items offered in restaurants without the labeling for each outcome described above, controlling for the item- and restaurant-level covariates described above. These analyses included an interaction term between year and voluntary labeling status to examine whether mean per item calories differed between chain restaurants with voluntary labeling and those without. We examined differences in mean per item calories among newly introduced items in 2014 between Chick-fil-A, McDonald’s, Panera, and Starbucks (all of which had voluntarily introduced national menu labeling) and their competitors that had not implemented labeling.

We present p values for all analyses because the data are treated as a sample generalizable to large restaurant chains. We adjusted standard errors to account for clustering at the restaurant level.

LIMITATIONS

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the data included menu items from only the largest US restaurant chains. These results are unlikely to be generalizable to other types of restaurants.

Second, MenuStat’s recording of information about calories may have been subject to error since the database captures calories from restaurants’ websites. However, previous studies have demonstrated that information about caloric content published by restaurants is highly accurate.12

Third, our measure of voluntary national menu labeling did not account for varying dates of implementation, which ranged from 2010 to 2013. This could have biased our results toward the null (that is, it could have led to our underestimating differences between restaurant chains). We anticipated results’ being biased toward the null in this case because some restaurants that labeled their menus contributed data during a time period when they did not use labeling.

Fourth, because only five of the sixty-six chains implemented labeling, with three of the five doing so in the period 2010–12, we did not have sufficient baseline data for restaurants with labeling to facilitate difference-in-differences analyses. As more data become available, a future study should be able to accommodate this type of analysis.

Fifth, although our ability to use census data is a strength of the study, the MenuStat data are a nonprobability sample. This limits inferences to the large chains included in this analysis.

Sixth, our estimates of mean per item calories at the restaurant level may vary based on how calories are reported in the MenuStat data. For example, there is no standardized serving size used to report per item calories, and some chains (such as those with “build your own” options) report component parts of a meal separately instead of collectively as a full meal. This causes their mean per item calories to appear artificially low.

Seventh, while our data are longitudinal, they do not allow for certainty in the direction of effects. For example, some restaurants may have been early adopters of calorie labeling because they prioritized lower-calorie menu items or healthy eating as part of their brand identity.

Eighth, the sixty-six restaurant chains included in this study are among the top hundred chains based on US sales. However, they may not be representative of all the top hundred chains.

Ninth, these data described menu items available for purchase, not sales. Therefore, the frequency with which lower-calorie items were purchased and the characteristics of customers who typically chose them are unknown.

Finally, we lacked sufficient sample size to conduct supplementary analyses such as analyzing restaurant chains separately over time.

Study Results

MENU ITEM CHARACTERISTICS

There were 3,675 items sold by the five restaurant chains that had information about calories posted: 697 (19 percent) were types of food, 2,494 (68 percent) were beverages, and the remaining 484 items (13 percent) were toppings or ingredients (Appendix Exhibit A2).15 The sixty-one chains that did not voluntarily label their menus sold 19,391 items: 11,345 (59 percent) were food items, 4,860 (25 percent) were beverages, and the remaining 3,186 items (16 percent) were toppings or ingredients.

Among chain restaurants that used voluntary menu labeling, 38 percent of menu items in 2013 and 24 percent in 2014 were new, compared to 16 percent and 15 percent, respectively, for chains without voluntary labeling.

CALORIE DIFFERENCES BY MENU LABELING STATUS, 2012–14

In each of the three years in the study period, average per item calories for all menu items in restaurants with voluntary labeling were significantly lower than those in restaurants without the labeling (Exhibit 1). No significant time trends were evident.

Exhibit 1.

Predicted Mean Per Item Calories For All Menu Items At Chain Restaurants, By Menu Labeling Status And Item Category, 2012–14

| Menu category | With voluntary menu labeling

|

Without voluntary menu labeling

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean calories

|

p value for trend | Mean calories

|

p value for trend | |||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |||

| Overall | 260.1 | 261.9 | 263.3 | 0.98 | 399.2**** | 398.1**** | 402.5**** | 0.79 |

| Fooda | 369.6 | 371.7 | 373.3 | 0.31 | 514.2**** | 512.5**** | 521.2**** | 0.34 |

| Beverages | 264.7 | 266.1 | 267.5 | 0.55 | 304.8** | 305.0** | 303.7** | 0.45 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from MenuStat (Note 12 in text) and data collected on restaurant characteristics and policies.

NOTES Mean per item calories in each year are predicted means from models that adjusted for children’s menu item status, whether an item was offered regionally or for a limited time only, whether a restaurant chain is national, the percentage of restaurant locations within each chain subject to local menu labeling regulation, and restaurant type (fast food, full service, fast casual). Significance refers to differences between restaurants with voluntary national menu labeling in each year and those without such labeling.

Includes all menu categories except beverages and toppings or ingredients.

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

Similarly, for items on menus in all three years, average per item calories in each year were significantly lower in restaurants with voluntary labeling compared to those without (Exhibit 2). Again, no significant time trends were evident.

Exhibit 2.

Predicted Mean Per Item Calories Among Items On Chain Restaurant Menus In All Years, By Menu Labeling Status And Item Category, 2012–14

| Menu category | With voluntary menu labeling

|

Without voluntary menu labeling

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean calories

|

p value for trend | Mean calories

|

p value for trend | |||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |||

| Overall | 234.6 | 235.7 | 238.3 | 0.28 | 355.6**** | 354.5**** | 359.8**** | 0.38 |

| Fooda | 362.5 | 365.5 | 366.2 | 0.35 | 463.9**** | 461.9**** | 472.3**** | 0.31 |

| Beverages | 209.1 | 207.7 | 215.1 | 0.27 | 265.1 | 266.1 | 264.3 | 0.57 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from MenuStat (Note 12 in text) and data collected about restaurant characteristics and policies.

NOTES Mean per item calories in each year are predicted means from models that adjusted for children’s menu item status, whether an item was offered regionally or for a limited time only, whether a restaurant chain is national, the percent of restaurant locations within each chain subject to local menu labeling regulation, and restaurant type (fast food, full service, fast casual). Significance refers to differences between restaurants with voluntary national menu labeling in each year and those without such labeling.

Includes all menu categories except beverages and toppings or ingredients.

p < 0.001

DIFFERENCES IN MEAN CALORIES AMONG NEW ITEMS BY MENU LABELING STATUS

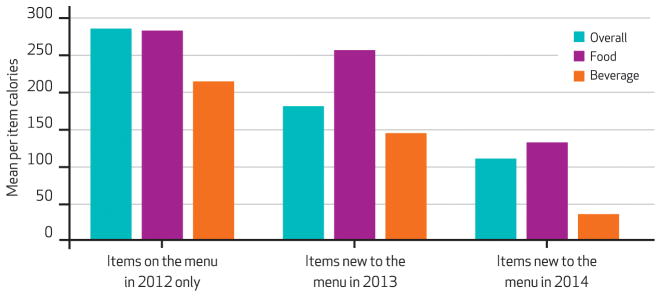

Compared to chain restaurants without labeling, those with voluntary labeling had lower calorie content for items that were on the menu only in 2012 (a difference of 286 kcal: 232 versus 519; p < 0.001) and lower calorie content for new menu items introduced in 2013 (a difference of 182 kcal: 263 versus 445; p < 0.001) and in 2014 (a difference of 110 kcal: 309 versus 419; p = 0.004) (Exhibit 3). The within-group difference in calories for new menu items in 2014 compared to items on the menu only in 2012 was significant among restaurants both with voluntary labeling (309 kcal versus 232 kcal; p = 0.02) and those without it (419 kcal versus 519 kcal; p = 0.001) (data not shown).

Exhibit 3. Predicted Difference In Mean Calories Between Restaurants Without Menu Labeling And Those That Voluntarily Implemented Menu Labeling Before 2014.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from MenuStat (Note 12 in text) and data collected about restaurant characteristics and policies. NOTES All differences are positive because restaurants without labeling had more calories, compared to those with labeling, for overall, food (all menu categories except beverages and toppings or ingredients), and beverage categories. Mean per item calories in each year are predicted means from models that adjusted for children’s menu item status, whether an item was offered regionally or for a limited time only, whether a restaurant chain is national, the percentage of restaurant locations within each chain subject to local menu labeling regulation, and restaurant type (fast food, full service, fast casual). The within-group difference in calories for new menu items in 2014 compared to items on the menu in 2012 only was significant among restaurants with labeling and among those without it.

Of note, the average number of calories remained lower throughout the study period in restaurants with voluntary menu labeling compared to those without such labeling. However, the mean per item calorie content actually increased over time in restaurants with voluntary labeling and decreased for those without (see Appendix Table A3).15

DIFFERENCES AMONG COMPETING CHAIN RESTAURANTS BY MENU LABELING STATUS

We compared Chick-fil-A to all other chicken restaurants, McDonald’s to all other hamburger restaurants, and Starbucks and Panera together to all other coffee chains and fast casual restaurant chains. We found that in chains with voluntary labeling, the new items introduced in 2014 had significantly fewer calories than the new items introduced in 2014 by their direct competitors. For example, the mean per item calories at Chick-fil-A were 267 kcal versus 375 kcal at other chicken restaurants (Exhibit 4). When we considered data for food and beverages separately, we noted significantly lower calories in food at Chick-fil-A versus other chicken restaurants, and in beverages at McDonald’s versus other hamburger restaurants and at Starbucks and Panera versus other coffee chains and fast casual restaurants.

Exhibit 4.

Predicted Mean Calories For Items Introduced In 2014 By Chain Restaurants With Voluntary Menu Labeling And By Competitors Without Such Labeling, By Restaurant Category And Item Category

| All restaurants | Chicken chains

|

Hamburger chains

|

Fast casual and coffee chains

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chick-fil-A | All others | McDonald’s | All others | Panera and Starbucks | All others | ||

| No. of locations | 2,090 | 12 | 65 | 269 | 855 | 468 | 401 |

|

| |||||||

| Overall | 400.0 | 266.8 | 374.7**** | 311.7 | 440.6 | 269.6 | 286.5 |

| Fooda | 491.9 | 273.8 | 417.0**** | 485.7 | 512.1 | 341.5 | 316.5 |

| Beverages | 416.7 | —b | —b | 324.3 | 514.2** | 288.3 | 292.6** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from MenuStat (Note 12 in text) and data collected about restaurant characteristics and policies.

NOTES Chick-fil-A, McDonald’s, Panera, and Starbucks used voluntary menu labeling. Mean calories in each year are predicted means from models that adjusted for children’s menu status and whether a restaurant chain is national. Significance refers to differences between restaurants with voluntary national menu labeling in each year and those without such labeling.

Includes all menu categories except beverages and toppings or ingredients.

Not available/applicable.

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

Discussion

We found that chain restaurants that voluntarily posted information about calories on their menus nationwide offered lower-calorie menu items compared to restaurants that did not post the information in terms of overall menu items, items that appeared on the menu in all three years of the study period, and new menu items introduced in 2013 and 2014. Average per item calories in each year were substantially lower in restaurants with voluntary labeling than in those without it. Chain restaurants with voluntary labeling also had new menu items with fewer calories compared to chain restaurants without. This finding persisted when we compared average calories in new items in 2014 at some of the chains with voluntary menu labeling and calories in new items at those chains’ direct competitors.

Notably, the within-group trends indicated an increase in mean per item calories among restaurants with voluntary labeling and a decrease in mean per item calories in restaurants without labeling. However, the absolute level of calories was lower among restaurants with voluntary labeling.

There were no significant time trends for menu items that were either offered in all of the three years or offered in only one of the three years (2012, 2013, or 2014) among restaurants with or without voluntary labeling. However, we did find that menu items at chains with voluntary labeling consistently had fewer calories than items at chains without the labeling. Taken together, these findings suggest that menu labeling might not have catalyzed reductions in calories in menu items. Instead, differences in calories might be a continuation of an already existing trend in chain restaurants that implemented labeling voluntarily.

Notably, the observed trends related to overall calories mask important heterogeneity in the types of items sold. Fewer mean per item food calories in chain restaurants with voluntary labeling are primarily related to changes in food, not beverages.

Policy Implications

The reasons we observed lower-calorie items across time in restaurants with voluntary labeling and reductions in calorie counts in those restaurants without labeling are not yet well understood, but we highlight several plausible explanations. First, restaurants may be anticipating public backlash after information about calories is posted and may be lowering the calories in their offerings as a result. Members of the public significantly underestimate the number of calories in the food they consume and may be surprised by how many calories certain items contain.2,16–18

Second, the constant media attention to high-calorie menu items and fast food in particular19 may spur voluntary reformulation of menu items. For example, a recent article in the New York Times showed that the typical order at Chipotle contains about 1,070 calories—twice as many calories as a Big Mac and “more than half of the calories that most adults are supposed to eat in an entire day.”20

Third, consumer demand may drive voluntary changes. Although only one-third of customers report noticing menu labeling in studies conducted in real-world settings,21,22 these customers tend be to female, white, and older than age thirty and to have higher income and educational attainment than the national average.21 This consumer group (mothers, in particular) is opinionated and active on social media, has significant purchasing power, and influences the majority of all purchase decisions.23

The transparency introduced by labeling may increase consumer demand for healthier items, which may be reflected in our finding that chains with voluntary menu labeling introduced approximately twice as many new items in 2013 and one-third more new items in 2014, compared to chains without voluntary menu labeling. Further evidence for this comes from some of the largest fast-food chains. Over time McDonald’s has added increasingly healthy items to its menu, introducing such items as specialty salads in 2003, snack wraps in 2006, fruit smoothies in 2010, and oatmeal in 2011. These actions have been emulated by competitors such as Wendy’s and Burger King.24

Fourth, fierce competition between chain restaurants for market share may also drive voluntary changes. Profit margins are the primary reasons why restaurants might offer or increase the amount of healthier food options.25 Some evidence suggests that menu labeling may even lead to increased revenue in the short term.26

Finally, voluntary changes could be the result of public relations efforts on the part of chain restaurants to improve perceptions of the healthfulness of their menu items. For example, in 2011 the National Restaurant Association launched the Kids Live Well initiative, a voluntary program that includes over 42,000 restaurants committed to offering healthy meal items for children.27

The reduction we noted in calories of new menu items for 2014 compared to 2012 for those restaurants without labeling may be a reaction to the upcoming federal rule requiring labeling of menus at large chain restaurants. However, the absolute number of calories was lower throughout the study period in restaurants with voluntary menu labeling than in those without.

Regardless of the mechanism, if the observed supply-side lower calorie amounts among chain restaurants with voluntary menu labeling proliferates after the implementation of federally required menu labeling, the implications for population obesity are considerable. Americans spend over $600 billion annually in the 990,000 restaurants across the United States.28 That amount represents almost one-half of all food dollars spent in 2010, and fast-food restaurants account for over one-third of restaurant sales.29 Fast-food consumption is associated with greater total caloric intake30,31 and increased body weight.32

Every day, one-third of the adults and children in the United States eat at fast food restaurants.33 Reducing purchases in chain restaurants by approximately 120 calories for standard items on restaurants’ menus and by approximately 146 calories for newly introduced items (the average differences in calories we observed between restaurants with and those without voluntary labeling) could help substantially reduce the daily number of excess calories that underlie the obesity epidemic in adults (estimated to be 220 calories per day)34 and children (estimated to be 165 calories per day).35

Together, the results from this study and previous studies that found little to no impact of local menu labeling on consumer calorie purchases3–5 suggest that the biggest impact of menu labeling may come in restaurant changes instead of in changes in individual behavior. Therefore, future evaluations of federal menu labeling should measure changes among consumers and restaurants.

Among restaurant chains, it will be particularly important to examine how calories are changing (for example, the number of calories in old versus newly introduced items), changes in which menu items are likely to have the most impact on public health, when restaurants decide to change (for example, immediately in response to future regulation or in response to competitors’ changes), and which chain is responding the most to these market forces. Recent research suggests that some restaurant types—such as quick-service restaurants with healthier signature items—might be more agile in adapting to menu labeling.36

Finally, we note that the implementation of nationwide menu labeling represents a major cultural shift. The effects of menu labeling should be understood as part of a broader trend toward the use of policies, through the public and private sectors, to improve the health of food environments. These policies include a proposed national ban on trans fat, school nutrition policies, and the pledge from the nation’s leading manufacturers of food and beverage consumer packaged goods to sell 1.5 trillion fewer calories in the US marketplace.37

Conclusion

Chain restaurants are ubiquitous in the United States and represent a significant source of calories for many Americans.29 Regardless of whether the differences in caloric content between large chain restaurants with voluntary menu labeling and those without it were prompted by the anticipated federal labeling requirements or by other forces, lower-calorie menu items, coupled with the expansive final rule for menu labeling, may be an important tool for helping consumers reduce their calorie intake. Because of the limited impact of calorie labeling on purchasing decisions3–5,38 and evidence suggesting that 70 percent of customers rarely alter their ordering habits when they go to a chain restaurant,39 the greatest impact of mandatory menu labeling on population health may come from restaurants’ changing the calories of their menu items instead of consumers’ changing their behavior. Since our results cannot prove causation, further research is necessary to test the nature of the associations we found between the voluntary use of menu labeling in chain restaurants and changes in the caloric content of menu items.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the New York City, Department of Health and Mental, Hygiene for the MenuStat data.

Contributor Information

Sara N. Bleich, Email: sbleich@jhu.edu, Associate professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in Baltimore, Maryland

Julia A. Wolfson, PhD candidate in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Marian P. Jarlenski, Assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Graduate School of Public Health, at the University of Pittsburgh, in Pennsylvania

Jason P. Block, Assistant professor in the Department of Population Medicine at Harvard Medical School, in Boston, Massachusetts

NOTES

- 1.Food and Drug Administration. Food labeling; nutrition labeling of standard menu items in restaurants and similar retail food establishments. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2014;79(230):71155–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton S, Creyer EH, Kees J, Huggins K. Attacking the obesity epidemic: the potential health benefits of providing nutrition information in restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1669–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swartz JJ, Braxton D, Viera AJ. Calorie menu labeling on quick-service restaurant menus: an updated systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:135. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiszko KM, Martinez OD, Abrams C, Elbel B. The influence of calorie labeling on food orders and consumption: a review of the literature. J Community Health. 2014;39(6):1248–69. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9876-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinclair SE, Cooper M, Mansfield ED. The influence of menu labeling on calories selected or consumed: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(9):1375–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long MW, Tobias DK, Cradock AL, Batchelder H, Gortmaker SL. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of restaurant menu calorie labeling. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):e11–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruemmer B, Krieger J, Saelens BE, Chan N. Energy, saturated fat, and sodium were lower in entrées at chain restaurants at 18 months compared with 6 months following the implementation of mandatory menu labeling regulation in King County, Washington. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(8):1169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center for Science in the Public Interest. State and local menu labeling policies [Internet] Washington (DC): CSPI; 2011. Apr, [cited 2015 Sep 22]. Available from: http://cspinet.org/new/pdf/ml_map.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleich SN, Wolfson JA, Jarlenski MP. Calorie changes in chain restaurant menu items: implications for obesity and evaluations of menu labeling. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strom S. New York Times. 2012. Sep 12, McDonald’s menu to post calorie Data. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahamian AA. Starbucks to post calorie labels in stores nationwide. Reuters [serial on the Internet] 2013 Jun 18; Available from: http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/06/18/us-starbucks-calories-idUSBRE95H0KD20130618.

- 12.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. MenuStat: methods [Internet] New York (NY): The Department; c 2015. [cited 2015 Sep 22]. Available from: http://menustat.org/methods-for-researchers/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powell LM, Han E, Zenk SN, Khan T, Quinn CM, Gibbs KP, et al. Field validation of secondary commercial data sources on the retail food outlet environment in the U.S. Health Place. 2011;17(5):1122–31. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liese AD, Colabianchi N, Lamichhane AP, Barnes TL, Hibbert JD, Porter DE, et al. Validation of 3 food outlet databases: completeness and geospatial accuracy in rural and urban food environments. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(11):1324–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of article online.

- 16.Block JP, Condon SK, Kleinman K, Mullen J, Linakis S, Rifas-Shiman S, et al. Consumers’ estimation of calorie content at fast food restaurants: cross sectional observational study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2907. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbel B. Consumer estimation of recommended and actual calories at fast food restaurants. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(10):1971–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandon P, Wansink B. Is obesity caused by calorie underestimation? A psychophysical model of meal size estimation. J Mark Res. 2007;44(1):84–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nixon L, Mejia P, Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Young S, Friedman LC, et al. Fast-food fights: news coverage of local efforts to improve food environments through land-use regulations, 2000–2013. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):490–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quealy K, Cox A, Katz J. New York Times. 2015. Feb 17, At Chipotle, how many calories do people really eat? [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breck A, Cantor J, Martinez O, Elbel B. Who reports noticing and using calorie information posted on fast food restaurant menus? Appetite. 2014;81:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elbel B, Kersh R, Brescoll VL, Dixon LB. Calorie labeling and food choices: a first look at the effects on low-income people in New York City. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(6):w1110–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winnett C. More proof moms are your best target: their brains are built for shopping. Forbes [serial on the Internet] 2012 Apr 25; [cited 2015 Sep 22]. Available from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/onmarket-ing/2012/04/25/more-proof-moms-are-your-best-target-their-brains-are-built-for-shopping/

- 24.Choi C. Burger King unveils new McDonald’s-inspired menu, rolls out huge marketing campaign. Associated Press; 2012. Apr 2, [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glanz K, Resnicow K, Seymour J, Hoy K, Stewart H, Lyons M, et al. How major restaurant chains plan their menus: the role of profit, demand, and health. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):383–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bollinger B, Leslie P, Sorensen A. Calorie posting in chain restaurants. Am Econ J Econ Policy. 2011;3(1):91–128. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Restaurant Association. Kids LiveWell Program [Internet] Washington (DC): The Association; [cited 2015 Sep 18]. Available from: http://www.restaurant.org/Industry-Impact/Food-Healthy-Living/Kids-LiveWell-Program. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Restaurant Association. 2014 restaurant industry pocket factbook [Internet] Washington (DC): The Association; [cited 2015 Sep 22]. Available from: http://www.restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/News-Research/research/Factbook2014_LetterSize.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Food-away-from-home [Internet] Washington (DC): USDA; [last updated 2014 Oct 29; cited 2015 Sep 28]. Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-choices-health/food-consumption-demand/food-away-from-home.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacoby J, Johar GV, Morrin M. Consumer behavior: a quadrennium. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:319–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowman SA, Vinyard BT. Fast food consumption of U.S. adults: impact on energy and nutrient intakes and overweight status. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23(2):163–8. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.French SA, Harnack L, Jeffery RW. Fast food restaurant use among women in the Pound of Prevention study: dietary, behavioral, and demographic correlates. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(10):1353–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell LM, Nguyen BT, Han E. Energy intake from restaurants: demographics and socioeconomics, 2003–2008. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, Chow CC, Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, et al. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):826–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60812-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM, Kuntz KM. Estimating the energy gap among US children: a counter-factual approach. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1721–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burton S, Howlett E, Tangari AH. Food for thought: how will the nutrition labeling of quick service restaurant menu items influence consumers’ product evaluations, purchase intentions, and choices? Journal of Retailing. 2009;85(3):258–73. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. The Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation pledge: calories sold from U.S. consumer packaged goods, 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):508–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Department of Agriculture. Scientific report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: advisory report to the secretary of health and human services and the secretary of agriculture [Internet] Washington (DC): USDA; 2015. Feb, [cited 2015 Sep 22]. Available from: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/pdfs/scientific-report-of-the-2015-dietary-guidelines-advisory-committee.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandau M. NPD: majority of restaurant customers won’t try new menu items. Nation’s Restaurant News [serial on the Internet] 2014 Jan 14; [cited 2015 Sep 22]. Available from: http://nrn.com/consumer-trends/npd-majority-restaurant-customers-won-t-try-new-menu-items.