Abstract

A randomized controlled trial tested an interactive normative feedback-based intervention—codenamed “FITSTART”—delivered to groups of 50–100 parents of matriculating college students. The 60-minute session motivated parents to alter their alcohol-related communication by correcting normative misperceptions (e.g., about how approving other parents are of student drinking) with live-generated data. Then, tips were provided on discussing drinking effectively. Incoming students (N = 331; 62.2% female) completed baseline measures prior to new-student orientation. Next, at parent orientation in June, these students’ parents were assigned to either FITSTART or a control session. Finally, four months later, students completed a follow-up survey. Results revealed that students whose parents received FITSTART during the summer consumed less alcohol and were less likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking (HED) during the first month of college. These effects were mediated by FITSTART students' lower perceptions of their parents' approval of alcohol consumption. Further, FITSTART students who weren’t drinkers in high school were less likely to initiate drinking and to start experiencing negative consequences during the first month of college, while FITSTART students who had been drinkers in high school experienced fewer consequences overall and were significantly more likely to report that they did not experience any consequences whatsoever during the first month of college. Importantly, FITSTART is the first PBI to impact HED, one of the most well-studied indicators of risky drinking. Thus, interactive group normative feedback with parents is a promising approach for reducing college alcohol risk.

Keywords: parent-based intervention, alcohol, college, normative feedback

A Parent-Based Intervention Reduces Heavy Episodic Drinking Among First-Year College Students

Contrary to the common notion that parental influence wanes as children transition from high school to college, there is growing evidence that parents continue shaping their children’s drinking behaviors both during and after this transition period (Abar, Abar, & Turrisi, 2009; Ham & Hope, 2003). For example, students who perceive their parents as less approving of drinking are less likely to drink (Abar et al., 2009), engage in “binge” or problem drinking (Abar, Turrisi, & Mallett, 2014; Hummer, LaBrie, & Ehret, 2013) and experience alcohol-related negative consequences (LaBrie, Hummer, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2010) relative to those who see their parents as more approving. Seeking to leverage parents’ protective influence, some researchers have turned to parent-based interventions (PBIs). In a typical PBI, handbooks on how to communicate with college students about alcohol are mailed to parents of incoming first year students during the summer prior to matriculation (see Turrisi, R. J., Jaccard, Taki, Dunnam, & Grimes, 2001). This approach has proven successful at reducing the odds that nondrinking high school students will initiate alcohol use during the first year of college (Ichiyama et al., 2009) and has produced inconsistent but modestly promising effects on general alcohol consumption (e.g., Doumas, Turrisi, Ray, Esp, & Curtis-Schaeffer, 2006; Ichiyama et al., 2009; Turrisi, Jaccard, Taki, Dunnam, & Grimes, 2001; Turrisi et al., 2009).

Concerns with Parent-Based Intervention Approaches

Despite the somewhat encouraging results of early PBI trials, the approach has not enjoyed widespread enthusiasm; resources consistently continue to be directed toward interventions focused on peer influence. One major concern with PBIs to date has been their inability to reduce heavy episodic drinking, or HED—defined as five or more drinks during a two hour period for men and four or more drinks for women (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2013). In fact, not a single one of the five PBI trials that directly tested HED as an outcome reported a significant effect on growth of or initiation into HED. Specifically, neither the initial efficacy study (N=154), two later handbook RCTs (N=724; N=443), nor a web-based PBI study (N=279) found that student assignment to the treatment condition (in which parents were given materials on effective alcohol-related communication strategies) was associated with any significant effect on HED during the fall semester (Donovan, Wood, Frayjo, Black, & Surette, 2012; Doumas, Turrisi, Ray, Esp, & Curtis-Schaeffer, 2013; Ichiyama et al., 2009; Turrisi et al., 2001). Similarly, a 2-year multicomponent intervention study (N=1014) found that students assigned to the PBI condition did not differ significantly on any alcohol-related outcomes, including HED, relative to control students, across follow-up intervals of both 10 months and 22 months (Fernandez, Wood, Laforge, & Black, 2011). Further, when the authors combined this PBI with a brief motivational student intervention it still failed to produce a synergistic effect on HED.

One promising finding reported by Doumas and colleagues (2013) is that students assigned to a “PBI+Booster” condition (their parents received a handbook during the summer as well as booster brochures throughout the following months) reported significantly less drinking to intoxication and lower peak consumption during the fall semester relative to PBI and control students—though HED was still not affected. Additionally, though a large-scale PBI study focused on mother-daughter dyads (N=978) found no effect on “heavy drinking”—a composite variable that included items assessing drunkenness tendencies and HED (Testa, Hoffman, Livingston, & Turrisi, 2010)—a different PBI that included booster telephone calls to parents throughout the summer in addition to mailed handbooks (N=656) did report an effect for a similar “heavy drinking” composite variable (Turrisi, Abar, Mallett, & Jaccard, 2010). Taken together, these findings suggest that, while a PBI handbook alone may not be enough to reduce HED, interventions that engage and motivate parents more deeply can potentially influence indicators of problematic alcohol consumption. One method for augmenting parental motivation that remains unexplored is to utilize the social norms approach (Berkowitz, 2004).

Extending Social Norms Approaches to Parents

Social norms are beliefs about whether or not other people perform and approve of a given behavior (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990). With regard to college student drinking, normative beliefs about how much the typical college student drinks (descriptive norms) as well as beliefs about how approving peers are of alcohol consumption (injunctive norms) are among the strongest known predictors of weekly drinking (Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007). Because students consistently misperceive these norms—overestimating the drinking behaviors and attitudes of other students (Perkins, 2002)—many interventions have successfully reduced student drinking by correcting participants’ normative beliefs (e.g., Lewis & Neighbors, 2006; Borsari & Carey, 2000; Lewis & Neighbors, 2006; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004).

Recent evidence suggests that, like students, parents are also influenced by normative perceptions with respect to their children’s drinking in college. For instance, parents who believe other parents communicate frequently with their children about drinking are more likely to communicate frequently with their own children, compared to parents who believe others communicate infrequently (Napper, Hummer, Lac, & LaBrie, 2014). Moreover, parents typically underestimate how often other parents communicate with their children about alcohol (Napper et al., 2014; Linkenbach, Perkins, & DeJong, 2003) and overestimate how approving other parents are of student drinking (LaBrie, Hummer, Lac, Ehret, & Kenney, 2011), beliefs which may lead them to communicate less often and convey a more approving attitude about alcohol use with their own children. In addition, parents have been shown to underestimate how often their own child consumes alcohol (LaBrie, Napper, & Hummer, 2014; Bylund, Imes, & Baxter, 2005), which may also cause them to be less motivated to initiate a conversation about drinking—viewing it as not needed for their students—than they would be if they held more accurate beliefs. Just as correcting students’ alcohol use norms leads to changes in their drinking-related attitudes and behaviors, social norms theory predicts that correcting parents’ alcohol communication norms would similarly influence them to adopt less approving attitudes and become more motivated to increase their alcohol-related messaging.

Given that parents have the ability to influence students’ heavy drinking behaviors if properly motivated, and given that norm correction interventions have consistently been found to motivate behavioral change, a PBI that corrects parent misperceptions in addition to providing tips on how to communicate about drinking could prove effective at reducing HED and other alcohol-related risks. One limitation of normative feedback approaches is that the effectiveness may be diminished if participants question the validity or source of the feedback presented or if the information is confusing (Fabiano, 1999; Granfield, 2002; Thombs, Dotterer, Olds, Sharp, & Raub, 2004). Indeed, some studies have found that only 40% of individuals presented with normative feedback view the normative data as believable (Thombs et al., 2004; Granfield, 2002); participants may question the source or reliability of the data and, thus, remain unpersuaded and unlikely to change their behavior. Further, the salience of the feedback may be better when individuals see themselves as members of the group from which the norms are drawn. LaBrie, Hummer, Neighbors, and Pederson (2008) developed an interactive intervention format in which the normative statistics are generated live by participants in a group setting. Using handheld wireless keypads, groups of students reported (1) their perceptions of how approving of drinking the other students in the room were, (2) their perceptions of how much alcohol the other students in the room consumed, and (3) their own approval levels and drinking behavior. Histograms of the data were then immediately projected on a large screen and students were shown the extent to which they tended to overestimate both the approval of the others in the room and their actual consumption. This interactive normative feedback approach was effective at correcting normative misperceptions and reducing drinking across a follow-up period of two months. A similar approach, using normative data generated in-vivo to increase believability and saliency, may be a successful approach with parents.

The Current Study

The current study evaluated a social norms-based intervention for parents of first-year college students delivered during a summer orientation session. The primary aim was to develop a PBI that would demonstrate efficacy not only in delaying alcohol initiation, but in reducing HED as well. The intervention, termed “Parent Feedback Intervention Targeting Student Transitions and Alcohol Related Trajectories” (Parent FITSTART), incorporated both normative feedback generated live during an orientation session and information regarding effective parent-child communication. We hypothesized that there would be less overall alcohol consumption and HED among those students whose parents were assigned to receive the FITSTART intervention, relative to those whose parents were assigned to the treatment-as-usual control group (H1). Further, it was anticipated that (a) students’ reports of their parents’ frequency of communication about alcohol and (b) students’ perceptions of their parents’ alcohol approval would mediate the effects of the intervention on both overall student consumption and HED. That is, we expected that the intervention would reduce parents’ approval of drinking and increase the extent to which they communicate with their children about alcohol use, thereby impacting student alcohol behaviors (H2). Lastly, FITSTART was hypothesized to be effective both at delaying alcohol initiation among students who had not used alcohol prior to college and at reducing HED and negative consequences among students who drank in high school (H3).

Method

Participants

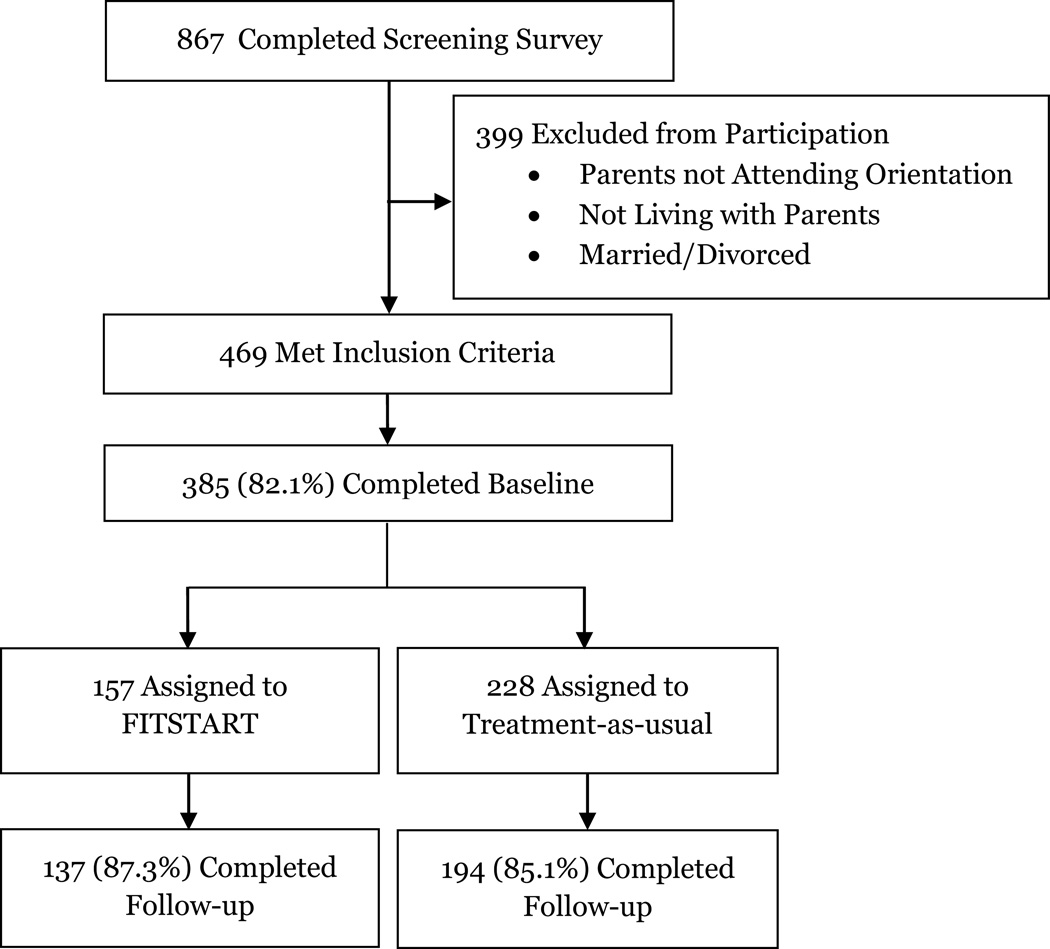

In May of 2014, prior to summer orientation, members of the incoming first-year class (N = 1233) at a mid-size, private west coast university in the United States were invited to complete a brief screening survey to determine if they were eligible to take part in a study about the transition to college. A total of 867 students completed screening and 469 were deemed eligible for participation (currently under 21, living with their parents, and planning to attend summer orientation with a parent). Of these 469 eligible students, 385 (82.1%) completed the baseline survey. Of these 385 initial study participants 331 (86.0%) completed a follow-up survey four months later, during October—this follow-up period was selected because the majority of previous PBI studies have utilized an assessment during the fall semester to measure short-term intervention effects (e.g., Turrisi et al., 2001; Doumas et al., 2013; Ichiyama et al., 2009; Donovan et al., 2012; Testa et al., 2010). See Figure 1 for a recruitment flow chart. Demographic characteristics of the final student sample are presented in Table 1. The parent sample consisted of 422 individuals (98 men, 324 women) representing the 385 students—37 students were represented by two parents.

Figure 1.

Participation flow diagram.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographics characteristics alcohol use and parent-related variables overall and by study condition.

| Overall (N = 331) |

Intervention (N = 137) |

Control (N = 194) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | M (SD) | % (N) | M (SD) | % (N) | M (SD) | ||

| Age | |||||||

| Years | 17.76 (.47) | 17.81 (.43) | 17.73 (.49) | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 37.8 (125) | 36.5 (50) | 38.7 (75) | ||||

| Female | 62.2 (206) | 63.5 (87) | 61.3 (119) | ||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 18.4 (61) | 17.5 (24) | 19.1 (37) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 81.6 (270) | 82.5 (113) | 80.9 (157) | ||||

| Race | |||||||

| Asian | 11.8 (39) | 13.1 (18) | 10.9 (21) | ||||

| Black or African American | 6.4 (21) | 4.4 (6) | 7.8 (15) | ||||

| White or Caucasian | 61.5 (203) | 60.6 (83) | 62.2 (120) | ||||

| More Than One Race | 12.7 (42) | 14.6 (20) | 11.4 (22) | ||||

| Other | 7.6 (25) | 7.3 (10) | 7.8 (15) | ||||

| Baseline Outcomes | |||||||

| Initiated Drinking | 74.3 (246) | 72.3 (99) | 75.8 (147) | ||||

| Recent HED | 20.5 (68) | 17.5 (24) | 22.7 (44) | ||||

| Weekly Drinks | 2.26 (4.34) | 1.84 (3.67) | 2.57 (4.61) | ||||

| Parent Alcohol Communication Frequency | 2.93 (2.37) | 2.93 (2.37) | 2.92 (2.37) | ||||

| Perceived Drinks Acceptable to Parents | 1.77 (1.80) | 1.70 (1.65) | 1.82 (1.91) | ||||

| Negative Consequences | .63 (1.01) | .60 (.92) | .66 (1.07) | ||||

| Follow-up Outcomes | |||||||

| Initiated Drinking | 80.7 (267) | 74.5 (102) | 85.1 (165)* | ||||

| Recent HED | 37.5 (124)** | 29.9 (41)* | 42.8 (83)** | ||||

| Weekly Drinks | 4.53 (7.68)** | 3.14 (6.01)** | 5.48 (8.53)** | ||||

| Alcohol Communication Frequency | 3.78 (2.48)** | 3.62 (2.53)** | 3.90 (2.45)** | ||||

| Perceived Drinks Acceptable to Parents | 2.02 (1.80)** | 1.80 (1.64) | 2.17 (1.87)** | ||||

| Negative Consequences | 1.09 (1.62)* | 1.08 (1.44)* | 1.09 (1.85)* | ||||

Note. Asterisks next to follow-up measures indicate significant changes from baseline to follow-up for a specific measure; there were no significant differences by intervention condition for demographics or outcome variables at baseline.

p < .01;

p < .05.

Procedure

The study was IRB approved and the university’s registrar provided contact information for all incoming students and their parents, who were sent invitation emails and letters during the month of May. The parent letter began, “research has demonstrated that parents have a significant impact on their child’s health-related decisions and behaviors during this transitional period” and went on to inform parents that a study was being conducted about how the university could best support parents during this time. It was emphasized that, in order to participate, all parents would have to do was to attend summer orientation with their student. Meanwhile, the student letter framed the study as “a research project examining health-related issues during the transition from high school to college”, and informed students that the study would include a follow-up survey during the fall semester. The only requirement outlined was that the student must attend summer orientation along with a parent. Interested students who were 18 years and older consented electronically during screening and, if eligible, were immediately directed to the baseline survey. For students under the age of 18, parental consent was obtained before students were emailed a link to the baseline survey. Students who both completed the baseline survey and had a parent participate in summer orientation were emailed four months later (one month into their fall semester) with a link to a follow-up questionnaire. Participants received $30 for completing the baseline survey and $20 for the follow-up.

The university hosts six separate two-day orientations for both new students and their parents during the month of June. Parent and student programming is conducted concomitantly in separate locations on campus with children spending the night in the dorms and not being reunited with their parents until after the final session on day two. Thus, only parents were present at the FITSTART sessions. The parent orientation programming includes a variety of informational sessions focused on campus life (e.g., student finances, student housing services, meal plans, academic expectations, campus safety). The intervention session (listed on parents’ schedules as “How Parents Matter During the Transition into College”) and an information technology session which served as a control for the study were scheduled in the afternoon of the second day of each orientation. Parents in both conditions attended all other regularly-scheduled orientation workshops and presentations together, receiving the university’s typical alcohol-related programming including a lecture given by student psychological services and a talk with public safety about campus alcohol and drug policies. Thus, the comparison group is considered a treatment-as-usual control. Because the intervention contained gender-specific information, parents were block-randomized to condition on a given day based on the gender of their child. Assignment was counterbalanced so that for three of the sessions, parents of males received the intervention while parents of females received the control session, and during the other three sessions parents of females received the intervention while parents of males received the control session. Both intervention and control sessions lasted approximately one hour.

Measures

Alcohol experience and overall weekly use

Weekly drinking quantity was measured at both assessments using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999), which asked participants to think about a typical week during the past 30 days and estimate the number of drinks they consumed on each day of the week. Responses were aggregated across drinking days to create an overall drinks per week measure. Additionally, at baseline, participants were asked to classify their drinking during the past year by selecting one of five options. Those who selected either “I have never tried alcohol” or “I have tried alcohol but abstain from drinking” were classified as alcohol inexperienced while those who selected either “I am a light drinker”, “I am a moderate drinker”, or “I am a heavy drinker” were classified as alcohol experienced.

Heavy episodic drinking

Recent HED was assessed by asking students to report the number of occasions on which they consumed five (males) / four (females) drinks in a row during the past two weeks. Because the large majority of participants reported that they did not engage in HED at all or engaged in HED only once during the past 2 weeks at both baseline and follow-up, we elected to combine the roughly 6% of the sample that reported more than 1 HED occasion with those who reported engaging in HED once. Thus, our HED measure indicates the proportion of students who engaged in HED during the 2 weeks prior to assessment (i.e. Recent HED).

Frequency of parent-initiated alcohol-related communication

Participants indicated how often in the past three months each of their parents initiated a conversation with them about alcohol with options ranging from 1 (Never) to 7 (More than once a week). To account for the fact that students reported relationships with different numbers of parents (e.g. single mother only, mother, father, stepfather, etc.), the response for the parent who most frequently initiated alcohol communication was used as the indicator of parent-initiated frequency.

Perceived parental alcohol approval

Participants estimated (1) the number of drinks their parents would approve of them consuming on a typical occasion and (2) the maximum number of drinks their parents would approve of them consuming on any occasion. The two responses were averaged to form a composite for perceived parental approval (correlations between items at baseline and follow-up were r = .76 and r = .81).

Alcohol-related consequences

The consequences measure used in the current study, adapted from Turrisi and Ray (2010), consisted of nine items (α = .77) from the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006) and the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (Hurlbut & Sher, 1992) representing physical, sexual, and academic consequences. The items for physical consequences were: “I have had a hangover (headache, sick stomach) the morning after I had been drinking”, “I have had less energy or felt tired because of my drinking”, and “I have felt very sick to my stomach or thrown up after drinking”. The items assessing academic consequences were: “The quality of my work or schoolwork has suffered because of my drinking”, “I have not gone to work or missed classes at school because of drinking, a hangover, or illness caused by drinking”, and “I have neglected my obligations to work, family, or school because of drinking”. The final three items assessing sexual consequences were: “I have had sex when I didn’t really want to because I was drinking”, “I have been pressured or forced to have sex with someone because I was too drunk to prevent it”, and “I have pressured or forced someone to have sex with me after I have been drinking”. Response options were anchored on a five point scale and ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (10 or more times) during the previous two weeks. A single sum score was computed.

Parent Intervention and Control Sessions

Parents were issued a clicker as they checked in for the FITSTART session. These small wireless keypads, part of the interactive polling system OptionFinder™, allow users to enter numerical responses to questions projected on a screen using PowerPoint-based software. The resulting histograms can be immediately displayed. The FITSTART presentation began with a series of sample questions assessing parent age, gender, and home state to familiarize parents with the technology. The presenter then explained how to interpret each of these graphical displays. The immediate feedback was expected to increase parents’ interest and belief in the accuracy of the subsequent data presented (LaBrie et al., 2008). Next, this immediate visual feedback was turned off and parents answered questions about their perceptions of student drinking (e.g., “How many drinks per week do you think the typical freshman student consumes?” vs “How many drinks per week do you think your daughter will consume during her first year of college?”), about their normative beliefs with regard to parent alcohol acceptability (e.g., “How many drinks per week does a typical parent think it is acceptable for their freshman daughter to consume?” vs “How many drinks per week is it acceptable for your daughter to consume during her first year of college?”), and with regard to parent-child alcohol-related communication (e.g., “What percentage of parents have spoken to their college-aged daughter about alcohol use in the past 3 months?” vs “Have you spoken to your daughter about alcohol use in the past 3 months?”).

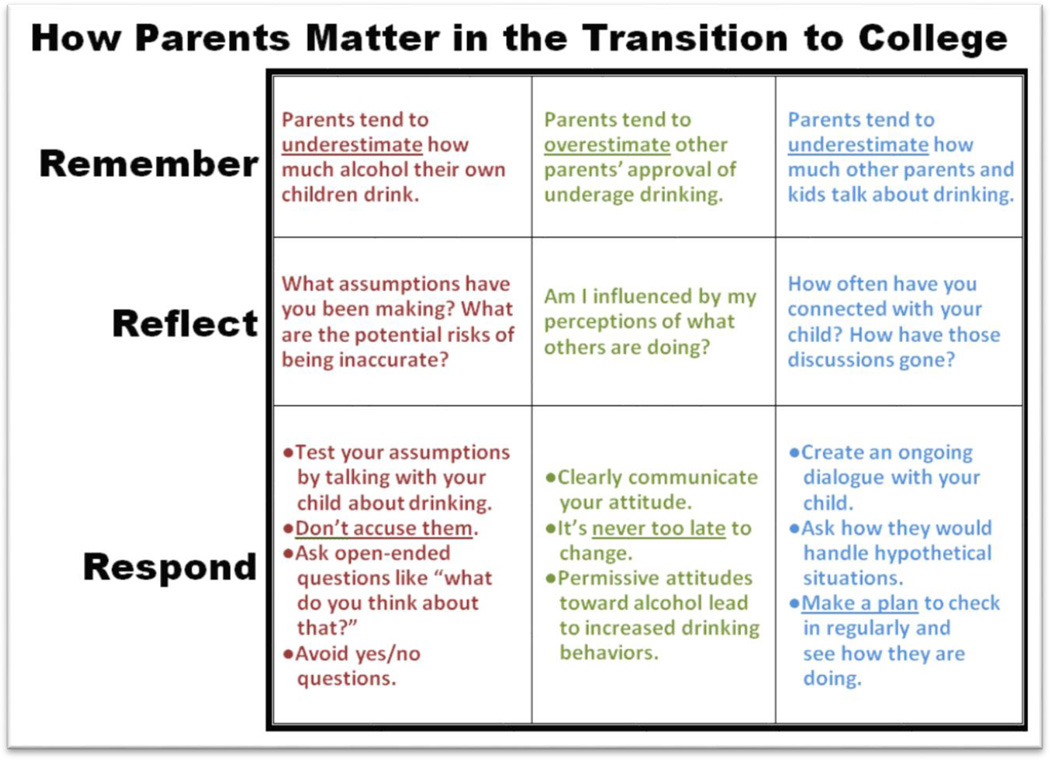

After participants had answered all of the questions, histograms of the aggregated answers were presented alongside national and campus averages. The facilitator led parents through the slides noting first what they as a group thought other parents believed or did and then comparing that to what they as a group actually believed or did, noting where participants over/underestimated group norms and campus/national parent norms. After presenting the in-session derived responses, the facilitator emphasized three key observations: first, participants were shown how they, as a group, tended to overestimate how accepting other parents are of drinking; second, they saw how they tended to underestimate the extent to which other parents speak to their children about alcohol; third, it was emphasized that they tended to underestimate how much their child would drink in college.

As an augmentation to the interactive normative feedback presentation, the facilitator then highlighted research findings demonstrating parents’ continued influence on their students’ alcohol use decisions during the transition to college and discussed recommended strategies for approaching the subject of drinking with their transitioning children (based on Turissi, 2009). Parents were given examples of conversation starters and open-ended questions to lower their children’s defensiveness and engage in a meaningful dialogue. For instance, one recommended technique was to generate hypothetical situations involving alcohol and ask students how they might navigate such scenes. The final phase of the presentation dealt with questions that teens commonly ask during these talks, like “How much did you drink in college?”, along with some options of how one might respond to these inquiries. Appendix A contains a copy of the card given to parents who attended the intervention, highlighting the key concepts discussed.

While the intervention session was taking place, parents in the control condition received a presentation on information technology at which no alcohol-related information was given. Parents were instructed on using the university’s online system for paying bills and purchasing meal plans. Further, campus resources were covered so parents would know where to direct their students for assistance with technical and computer-related questions. Parents in the FITSTART condition were given this information in the form of a handout.

Data Analytic Plan

Tests of H1 examined the effects of the FITSTART intervention on student weekly drinking, recent HED, and parent-focused constructs (student-reported parent-child communication and perceived parental approval) for the overall sample. Even after winsorizing to 3 standard deviations, the drinks per week outcome did not follow a normal distribution as the SD remained significantly higher than the mean. The distribution of weekly drinks was found to most closely approximate the negative binomial distribution as indicated by a chi-square/df value of 1.33 (Hilbe, 2014). Distribution-appropriate regression models examined the variability in drinks per week (negative binomial), HED (logistic), parent alcohol communication frequency (linear), and perceived parental approval (linear) associated with intervention condition after controlling for participants’ age, sex, race, and the baseline measure of the outcome.

In the presence of significant intervention effects for alcohol use variables and either of the hypothesized mediators (parent communication and perceived parental approval), tests of mediation, H2, were performed. For the binary HED outcome, mediation analyses were performed by PROCESS bootstrap test in SPSS (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Recommended guidelines for testing mediation using the Preacher and Hayes method were followed (e.g., 5,000 bootstrap samples and bias corrected confidence intervals; Hayes, 2009; Preacher and Hayes, 2004; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010). Intervention condition was specified as the independent variable (0 = control, 1 = intervention), the parent-related construct at follow-up as the mediator, and recent HED at follow-up as the outcome. For the negative binomial-distributed drinks per week outcome, tests of indirect effects for each mediator (also contingent on the presence of a significant intervention effect) were calculated in Mplus following recommendations from Muthen & Muthen (2001). Mediation models controlled for student’s age, sex, race, baseline measures of the outcome variables (recent HED, drinks per week), and baseline measures of the mediators.

H3 examined the ability of the FITSTART intervention to influence alcohol use and negative consequences among sub-samples of students both with and without alcohol experience at baseline. First, logistic regression models examined the likelihood of recent HED as a function of intervention condition among students already drinking at baseline. This model controlled for age, sex, race, and the baseline measure of HED. Next, because negative consequences yielded a zero-heavy count distribution among baseline drinkers, a zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression model estimated two components. First, holding constant both demographic covariates and the corresponding baseline measure of negative consequences (also modeled using a Poisson distribution), Poisson regression coefficients estimated the association between intervention condition and the frequency count of negative consequences. Second, while holding constant the same covariates, the likelihood of being in the excess zero class, or of not experiencing any consequences, was calculated for intervention condition. Alternatively, because the majority of students who had not yet consumed alcohol at baseline experienced 0 or 1 negative consequence by follow-up, a logistic regression model was preferred to the zero-inflated count model among this sub-sample. Thus, for students who had not yet consumed alcohol at baseline, logistic regression models predicted the respective likelihoods of alcohol initiation, recent HED, and the experience of 1 or more negative consequence as a function of intervention condition after controlling for age, sex, and race.

Results

Missing Data

As shown in Figure 1, 86.0% of the student participants assessed at baseline (N = 385) were re-assessed at follow-up (N = 331). The 54 students not assessed at follow-up were evenly distributed among parent intervention (20 dropped out, 137 assessed) and control conditions (34 dropped out, 194 assessed), χ2=.108, p = .74. Further, no differences were observed on any study or demographic variables between the students who dropped out and those who remained in the study through follow-up (all ps > .05). Beyond attrition, none of the variables analyzed in tests of hypotheses for the current paper were missing any data at either baseline or follow-up. Given the low rate of attrition and lack of differences between those who completed and did not complete the follow-up survey, list-wise deletion was used across analyses.

Preliminary Analysis

Table 1 provides descriptive information for demographic covariates as well as for baseline and follow-up measures of all outcome variables in the overall sample and by study condition. Chi-Square tests conducted among binary variables and t-tests conducted among continuous variables supported the equivalency of intervention and control groups at baseline. Chi-square and paired sample t-tests also indicated significant increases from baseline to follow-up for the majority of alcohol-related outcomes within the overall sample (as indicated by asterisks in the bottom portion Table 1). Notably, while there were significant baseline to follow-up increases in alcohol initiation and perceived drinks acceptable to parents among students in the control condition, these significant increases were not observed among students whose parents received the intervention. These differences suggest that the intervention may have prevented natural escalations in alcohol experimentation and parental alcohol permissiveness that occur during the first 6 weeks of college.

H1: Intervention Influences Weekly Drinks and Parent-Related Outcomes

Regression results for tests of Hypothesis 1 are presented in Table 2. First, the negative binomial regression model predicting drinks per week at follow-up indicated a significant effect for intervention group on number of weekly drinks (B = −.36, p =.03) with students of parents who were assigned to FITSTART consuming 30% fewer drinks per week than students of control parents during their first month in college. The logistic regression model predicting recent HED also indicated a significant effect for intervention condition (OR = .55, p = .02) with predicted probabilities of HED for students in the FITSTART group (.30) significantly less than those in the control condition (.43). Linear regression models examining potential parent mediators revealed an intervention effect only for perceived parental approval (B = −.26 p = .014), with students in the FITSTART condition perceiving their parents as finding significantly fewer drinks acceptable compared to students in the control condition. However, there was no significant intervention effect for parent-initiated communication frequency (B = −.02, p = .89), suggesting that any observed effects on student alcohol use variables were not fostered by increases in parent messaging as a result of the intervention.

2.

Summary of regression results for intervention condition predicting drinks per week, recent HED, and parental constructs for the overall sample (N=331).

| Negative Binomial Regression | ||||||

| Parent Intervention Condition (Control = 0; FITSTART = 1) |

||||||

| Outcome | B | SE B | Z | OR | 95% CI (OR) | |

| Drinks per Week | −.36 | .16 | 4.63* | .69* | .50–.96 | |

| Logistic Regression | ||||||

| Parent Intervention Condition (Control = 0; FITSTART = 1) |

||||||

| Outcome | B | SE B | Wald x2 | OR | 95% CI (OR) | |

| Recent HED | −.60 | .27 | 4.83* | .55* | .32–.95 | |

| Linear Regression | ||||||

| Parent Intervention Condition (Control = 0; FITSTART = 1) |

||||||

| B | SE B | t | Fchange | R2 change | ||

| Parental Alcohol Communication Frequency | −.02 | .16 | .14 | .08 | .00 | |

| Perceived Drinks Acceptable to Parents | −.29 | .12 | −2.46* | 5.53* | .01 | |

Note. All models control for participant age, sex, race, and baseline measure of outcome.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

H2: Tests of Perceived Parental Approval as an Explanatory Mechanism

Given the finding of an intervention effect for parental approval but not for communication frequency, mediation models were constructed to test students’ perceptions of the number of drinks acceptable to their parents as a mediator of the relationship between intervention condition and both (1) weekly drinks and (2) HED (See Figure 2). For the model predicting weekly drinks, the intervention significantly predicted students’ perceptions of the number of drinks acceptable to their parents at follow-up (B = −.27, p = .02), and this mediator subsequently predicted drinks per week consumed by students at follow-up (B = .25, p < .001). Further, there was a significant indirect effect from the intervention to weekly drinking via students’ perceptions of drinks acceptable to parents, B = −.06, 95% CI [−.13, −.01]), and a non-significant direct effect from the intervention to weekly drinks, B = −.06, 95% CI [−.39, .27]. Similarly, for the model predicting likelihood of recent HED, the intervention significantly predicted students’ perceptions of the number of drinks acceptable to their parents at follow-up (B = −.25, p = .03), and this mediator subsequently predicted likelihood of HED at follow-up (B = .69, p < .001). Further, there was a significant indirect effect from the intervention to HED via students’ perceptions of drinks acceptable to parents, B = −.17, 95% CI [−.34, −.03], as well as a non-significant direct effect from the intervention to HED, B = −.48, 95% CI [−1.07, 0.09]. The supported mediation models demonstrate that FITSTART indirectly fostered reductions in weekly drinking and likelihood of HED by decreasing the number of drinks students perceived their parents to find acceptable for them to consume.

Figure 2.

Supported mediation model with unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors for all paths including the (total effect) of x on y. *p < .05; **p < .01.

H3: Intervention Effects among Alcohol Inexperienced and Experienced Students

As presented in Table 3, among students who had not yet initiated alcohol use at baseline (n = 129), the logistic regression model examining the likelihood of college alcohol use initiation by follow-up revealed a significant intervention effect (OR = .45, 95% CI [.21, .93]) with the predicted probability of initiation for students in the intervention group (.40) significantly reduced relative to control (.63). Additionally, the model predicting likelihood of experiencing negative consequences among baseline non-drinkers indicated a significant intervention effect (OR = .31, 95% CI [.11, .82]) with the predicted probability of experiencing consequences for participants in the intervention group (.12) significantly reduced relative to control (.21). However, in the model predicting HED among the baseline non-drinkers, the intervention effect did not reach statistical significance (OR = .68, 95% CI [.16, 1.95], with only slightly reduced predicted probabilities of HED for FITSTART students (.07) relative to control (.12).

Table 3.

Summary of logistic and zero-inflated Poisson regression models for intervention condition predicting alcohol use and negative consequences among students Alcohol Inexperienced and Experienced at baseline.

| Alcohol-Inexperienced Sub-sample (N=129) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Intervention Condition (Control = 0; FITSTART = 1) |

|||||

| Student Outcome | B | SE B | Wald x2 | OR | 95% C.I. (OR) |

| Alcohol Use Initiation | −.81 | .38 | 4.55* | .45* | .21 – .93 |

| Recent HED | −.62 | .63 | .78 | .68 | .17 – 1.97 |

| Negative Consequences | −1.19 | .51 | 5.41* | .31* | .11 – .82 |

| Alcohol-Experienced Sub-sample (N=202) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Intervention Condition (Control = 0; FITSTART = 1) |

|||||||

| Student Outcome | B | SE B | Z | Wald x2 | OR | 95% C.I. (OR) | |

| Recent HED | −1.04** | .37 | 9.46** | .36** | .18 − .69 | ||

| Negative Consequences | Count | −0.34** | .11 | −3.10* | .71** | .57 − .88 | |

| Logit | −0.73* | .44 | −0.73 | .72* | .26 − .89 | ||

Note. Models among alcohol inexperienced students control for participants’ age, sex, and race. Models for alcohol experienced students control for participants’ age, sex, race, and baseline measure of the outcome variable.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Intervention effects for HED were concentrated among students who were already drinking at baseline (OR = .36, 95% CI [.18, .69]); as the predicted probability of an alcohol experienced student engaging in HED at follow-up was substantially reduced if the student’s parent attended FITSTART (.41) relative to control (.65). Also presented in Table 3 is the zero-inflated Poisson regression model exploring whether intervention condition was related to the experience of alcohol-related consequences among the alcohol-experienced students (n = 202). The significant regression coefficient for the count portion of the model indicates that alcohol-experienced students in the intervention condition exhibited significantly fewer consequences than did alcohol-experienced control students. Further, the significant coefficient for the logit portion of the model indicated that alcohol-experienced students in the FITSTART condition had significantly increased odds of experiencing no physical consequences (e.g. being an excess zero), relative to control students.

Discussion

The current paper presents the results of a preliminary RCT for a novel parent-based college alcohol intervention—codenamed “FITSTART”—which lasted 60 minutes and was delivered live to groups of 50–100 parents during summer orientation prior to students’ initial arrival on campus. Parental assignment to the FITSTART condition, relative to a treatment-as-usual control group, was associated with students reporting less overall alcohol consumption during the first month of college (four months post-intervention). Further, students who had not yet begun to drink prior to the start of the study were significantly less likely to initiate alcohol use and to begin experiencing negative consequences during the first month of college if their parents had been assigned to attend the FITSTART session in June. Conversely, among students who were already drinkers at baseline, those whose parents had been assigned to FITSTART experienced fewer alcohol-related consequences, and were significantly more likely to report that they didn’t experience any consequences at all during the first month of college, relative to students whose parents had been assigned to the control session four months prior. Importantly, FITSTART is the first PBI to directly impact HED, one of the most well-studied indicators of risky drinking behavior. Though five previous PBIs failed to find an effect on HED, the novel methodology utilized in FITSTART (including live clicker technology and normative feedback for parents) resulted in a significant effect. Specifically, students in the intervention group who were drinkers prior to enrolling in the study were significantly less likely to engage in HED during their first month of college. Overall, these results suggest that pairing the communication tips that have characterized previous PBIs with a social norms component delivered live and designed to motivate parents to alter their drinking-related messaging may improve PBIs’ impact on more risky forms of alcohol consumption.

Effect sizes for the current study ranged from small to moderate across outcomes. These magnitudes are consistent with those reported in the brief college student intervention literature (Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007), and even compare favorably to effects observed for individually-delivered motivational interview-based student interventions (e.g., BASICS: Dimeff, 1999), which require a trained counselor to spend 45–60 minutes with each student. Further, the important effects found for reduced odds of engaging in HED were very robust.

Pathways of Intervention Influence

As hypothesized, students’ perceptions of their parents’ approval of drinking mediated the effect of FITSTART on student alcohol consumption. We had anticipated that parent-initiated communication may have been an additional mediator and yet it did not emerge as significant in the present investigation. A possible explanation for this finding may simply be that parents of heavier-drinking students engage in more reactive communication about drinking (Kam, 2011)—regardless of intervention condition. Several studies have found overall frequency of parental alcohol communication to be associated with greater student alcohol use (Abar, Fernandez, & Wood, 2011; Napper et al., 2014), likely representing escalations in parent messaging in reaction to student drinking rather than in anticipation. Thus, proactive increases in frequency of alcohol communication due to the intervention material may have been obscured by control parents’ reactive increases in alcohol communication frequency associated with their students’ greater alcohol use as college life began. Future evaluations of Parent FITSTART and other alcohol communication-related social norms interventions for parents should include assessments of both reactive and proactive parental alcohol communication frequency, communication quality, and message type from both students and parents.

An alternative, though yet untested, hypothesis is that, rather than increasing the frequency of communication, the intervention may have produced an increase in the effectiveness of parent-child interactions; perhaps parents are able to convey less approving attitudes without necessarily increasing the overall volume of communication. Indeed, research suggests that measures of communication frequency may not adequately capture the quality and content of parent messaging (Napper et al., 2014). Future research on similar PBIs should include more sensitive measures of alcohol-related communication designed to assess quality, content, and timing of both reactive and proactive messaging. Additionally, it may be important to explore parents’ self-reports of communication efforts following the PBI in addition to student self-reports, as parents’ reports of messaging levels have been shown to predict student alcohol consumption above and beyond students’ communication reports (e.g., Kandel & Andrews, 1987). In the present investigation we chose to focus on student perceptions of parent attitudes and messages rather than on parents’ reports of their own attitudes and messages because these student perceptions have more consistently been linked to student drinking behavior (Walls, Fairlie, & Wood, 2009; Turrisi & Ray, 2010). However, the fact that parent data was not collected here is a limitation of the current study.

Benefits to the FITSTART Approach

Promisingly, the data presented here reveal that parents can be an effective avenue through which to reach students at risk for heavy drinking, particularly during the critical period of the transition into college. Although past PBIs have produced some important outcomes, they have been largely ineffective at achieving meaningful reductions in the incidence or prevalence of HED. Perhaps parents of heavy-drinking students are less likely to read and act on the information given to them during traditional PBIs. Or perhaps such parents hold more permissive attitudes toward alcohol themselves and are therefore less motivated to talk to their child. Alternatively, it may be the case that these parents have attempted to discuss alcohol use with their children, but were unable to effectively convey their disapproval in a way that could be well-received and understood. Whatever the mechanisms underlying the null effects, the interactive and group-based nature of FITSTART may have been important for parents of HED students. Other parent-based interventions seeking to impact HED may benefit from adopting a similar approach to FITSTART, whereby parents are first convinced of the appropriateness of communicating less approving attitudes via normative feedback and are then presented ways to do so effectively.

Further, this study expands on the large literature for social norms-based college drinking interventions by showing that these principles can be applied to intervention techniques with parents. This represents a fruitful area for future innovation, implementation, and evaluation on a broader scale. Parent orientations are held on many college campuses, particularly on small to mid-sized campuses. Thus, an existing infrastructure is already in place that could be used to disseminate live PBIs like FITSTART. The intervention does not require individualized programming or 1-on-1 interaction; it is conducted in large groups in approximately 60 minutes and is therefore less labor-intensive than other more individually-tailored intervention approaches. Another key attribute of these sessions is the use of technology to generate normative feedback in order to enhance the believability of the statistics presented. Because the norms were generated in a live setting parents may have been more likely to view them as relevant and accurate compared to national or campus-wide averages. Indeed recent work supports the notion that this style of generating statistics makes parents feel comfortable conveying less approving attitudes to their children (Earle & LaBrie, in press).

Drawbacks to the FITSTART Approach

Conducting the FITSTART intervention requires significant preparation, infrastructure, and investment in equipment. Thus, an important question is whether the benefits outweigh the costs when comparing FITSTART to other PBI delivery modalities. By far the most well-documented format of PBI is the handbook developed by Turrisi and colleagues (2001). The costs of a handbook PBI are not negligible and include postage and printing fees associated with mailing handbooks to the household of every incoming student. Further, studies evaluating this method are not immediately generalizable because parents are typically compensated for reading the handbook and are asked to evaluate and return it to the research team (e.g., Fernandez et al., 2011; Ichiyama et al., 2009; Turrisi et al., 2001). In fact, one study that sent out handbooks without compensating parents—to better approximate how the PBI might be conducted by actual universities—did not find significant differences between treatment and control students on a single drinking-related variable (Doumas et al., 2013), further emphasizing the importance of motivating parents to change rather than just providing them with information. As a final note, though the intervention reported in the current paper utilized handheld wireless keypads, new technology exists today that would allow FITSTART to be delivered without this expensive equipment. Online polling platforms like www.polleverywhere.com and www.smspoll.net now give researchers the ability to conduct a FITSTART session without any additional equipment—parents can simply answer questions using text messaging on their cellphones and the results can be immediately displayed, just like with the wireless keypads used in the current study. Thus, the clear benefits of the FITSTART approach appear to outweigh the associated costs, especially if the clicker technology can be replaced with participants’ own smartphones.

Limitations and Future Directions

While these findings suggest FITSTART was effective at reducing student alcohol use and consequences during the transition into college, there are limitations in the scope and design of the current study. First, this study only reports short-term effects. The outcomes were assessed one month into students’ first semester of college (four months post-intervention). This assessment period allows for direct comparisons to other PBI studies, many of which have utilized a similar follow-up (e.g., Turrisi et al., 2001; Doumas et al., 2013; Ichiyama et al., 2009; Donovan et al., 2012; Testa et al., 2010). Also, the follow-up in this study was selected for clinical relevance as well, as the first six weeks of college has been identified as a particularly critical period for the formation of students’ future alcohol use patterns (NIAAA, 2002). However, further longitudinal research is needed to determine whether the observed effects will persist. Second, the relatively small sample recruited from a single private university limits generalizability. Parents who attend orientation are likely more engaged and involved in their students’ lives—relative to parents who choose not to attend—and, thus, this PBI modality may not be have the same effects on students with apathetic or disengaged parents. Future research expanding this type of intervention to an online community of parents, which would not require being physically present on campus, would allow us to test these assumptions. Third, this study did not assess parent-level data. Further investigation is necessary to determine whether the effects are moderated by other parenting factors. For example, it is possible that intervention efficacy is dependent on parenting style or quality of the parent-student relationship. More research is needed to determine how effective orientation-based interventions are for reaching parents of the most high-risk students.

It is also important to note that three different types of normative information were presented during FITSTART (feedback on student drinking, parent acceptability, and parent-student communication). Thus, it is unclear which was most beneficial or even whether all three are necessary. This topic will be important to address in upcoming studies. Another promising direction for future research involves combining a parent intervention like FITSTART with one of the many early prevention/intervention programs targeting incoming first-year students. Synergistic effects may emerge when students and parents are both engaged about alcohol-related topics (e.g., Cleveland et al., 2011; Mallett et al., 2010). Furthermore, FITSTART lasted only 60 minutes, the session occurred in June more than two months prior to matriculation, and no follow-ups were conducted with parents afterward. Other PBIs have enhanced their effectiveness by including conditions in which the initial intervention is paired with “boosters” delivered at later dates (e.g., Doumas et al., 2013; Mallett et al., 2011). Thus, testing different types of boosters delivered at various intervals post-intervention would be yet another valuable direction for the continued development of PBIs.

Conclusion

The initial success of FITSTART reported herein suggests that the addition of in-person interactively-generated normative feedback to interventions with parents of incoming college students represents a promising approach for reducing alcohol risk, particularly among students engaging in heavy drinking. Other colleges with existing parent orientations may wish to develop similar programs to discuss alcohol use and other important topics devoted to increasing the health and well-being of college students during the important developmental transition into college life.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant R21 AA021870 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A

References

- Abar C, Abar B, Turrisi R. The impact of parental modeling and permissibility on alcohol use and experienced negative drinking consequences in college. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abar CC, Fernandez AC, Wood MD. Parent–teen communication and pre-college alcohol involvement: A latent class analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1357–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abar CC, Turrisi RJ, Mallett KA. Differential trajectories of alcohol-related behaviors across the first year of college by parenting profiles. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:53. doi: 10.1037/a0032731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD. The social norms approach: Theory, research and annotated bibliography. Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse and Violence Prevention. US Department of Education. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund CL, Imes RS, Baxter LA. Accuracy of parents' perceptions of their college student children's health and health risk behaviors. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54:31–37. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.1.31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland MJ, Lanza ST, Ray AE, Turrisi R, Mallett KA. Transitions in first-year college student drinking behaviors: Does pre-college drinking moderate the effects of parent- and peer-based intervention components? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0026130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2011;34(2):210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY: US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan E, Wood M, Frayjo K, Black RA, Surette DA. A randomized, controlled trial to test the efficacy of an online, parent-based intervention for reducing the risks associated with college-student alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Turrisi R, Ray AE, Esp SM, Curtis-Schaeffer AK. A randomized trial evaluating a parent based intervention to reduce college drinking. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle AM, LaBrie JW. The upside of helicopter parenting: Engaging parents to reduce first-year student drinking. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2016.1165108. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano P. Learning lessons and asking questions about college social norms campaigns; Paper presented at the National Conference on the Social Norms Model: Science Based Prevention; Big Sky, MT. 1999. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AC, Wood MD, Laforge R, Black JT. Randomized trials of alcohol-use interventions with college students and their parents: lessons from the Transitions Project. Clinical Trials. 2011;8(2):205–213. doi: 10.1177/1740774510396387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R. Believe it or not: Examining to the emergence of new drinking norms in college. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Hayes B. Crosshatching in the Crosshairs: Sigma Xi Scientific Research Society. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical psychology review. 2003;23(5):719–759. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer JF, LaBrie JW, Ehret PJ. Do as I say, not as you perceive: Examining the roles of perceived parental knowledge and perceived parental approval in college students’ alcohol-related approval and behavior. Parenting Science and Practice. 2013;13:196–212. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2013.756356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41(2):49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiyama MA, Fairlie AM, Wood MD, Turrisi R, Francis DP, Ray AE, Stanger LA. A randomized trial of a parent-based intervention on drinking behavior among incoming college freshmen. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;(s16):67–76. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam JA. Identifying changes in youth's subgroup membership over time based on their targeted communication about substance use with parents and friends. Human Communication Research. 2011;37(3):324–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Andrews K. Processes of adolescent socialization by parents and peers. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1987;22(4):319–342. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Huchting K, Tawalbeh S, Pedersen ER, Thompson AD, Shelesky K, Neighbors C. A randomized motivational enhancement prevention group reduces drinking and alcohol consequences in first-year college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:149–155. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Grant S, Lac A. Immediate reductions in misperceived social norms among high-risk college student groups. Addictive behaviors. 2010;35(12):1094–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Huchting KK, Neighbors C. A brief live interactive normative group intervention using wireless keypads to reduce drinking and alcohol consequences in college student athletes. Drug and alcohol review. 2009;28(1):40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2008.00012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lac A, Ehret PJ, Kenney SR. Parents know best, but are they accurate? Parental normative misperceptions and their relationship to students' alcohol-related outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:521. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Pedersen ER. Live interactive group-specific normative feedback reduces misperceptions and drinking in college students: A randomized cluster trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(1):141. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(4):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Napper LE, Hummer JF. Normative feedback for parents of college students: Piloting a parent based intervention to correct misperceptions of students' alcohol use and other parents' approval of drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Who is the typical college student? Implications for personalized normative feedback interventions. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:2120–2126. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkenbach JW, Perkins HW, DeJong W. Parent's perception of parenting norms: using the social norms approach to reinforce effective parenting. In: Perkins HW, editor. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Ray AE, Turrisi R, Belden C, Bachrach RL, Larimer ME. Age of drinking onset as a moderator of the efficacy of parent-based, brief motivational, and combined intervention approaches to reduce drinking and consequences among college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1154–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Ray AE, Stapleton J, Abar C, Mastroleo NR, Larimer ME. Do parents know best? Examining the relationship between parenting profiles, prevention efforts, and peak drinking in college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2011;41:2904–2927. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Statistical analysis with latent variables. User's Guide," Version, 4. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Hummer JF, Lac A, LaBrie JW. What are other parents saying? Perceived parental communication norms and the relationship between alcohol-specific parental communication and college student drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:31–41. doi: 10.1037/a0034496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Changing the Culture of Drinking at US Colleges. Bethesda: The Task Force on College Drinking; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) [Retrieved July, 2015];Overview of Alcohol Consumption: Drinking Levels Defined. 2013 Retrieved from: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking.

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(s14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. The Sage Sourcebook Of Advanced Data Analysis Methods For Communication Research. Thousand Oak, CA: Sage; 2008. Assessing mediation in communication research; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Livingston JA, Turrisi R. Preventing college women’s sexual victimization through parent based intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science. 2010;11(3):308–318. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0168-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Dotterer S, Olds RS, Sharp KE, Raub CG. A close look at why one social norms campaign did not reduce student drinking. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53:61–68. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.2.61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R. A Parent Handbook for Talking With College Students About Alcohol. The Pennsylvania State University: Prevention Research Center; 2009. [Retrieved July, 2015]. Retrieved from: http://etownctc.org/handbookcollege.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Abar C, Mallett KA, Jaccard J. An examination of the mediational effects of cognitive and attitudinal factors of a parent intervention to reduce college drinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2010;40:2500–2526. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Ray AE. Sustained parenting and college drinking in first-year students. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52:286–294. doi: 10.1002/dev.20434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi RJ, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunnam H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:366–372. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi RJ, Mallett KA, Cleveland MJ, Varvil-Weld L, Abar C, Scaglione N, Hultgren B. Evaluation of timing and dosage of a parent-based intervention to minimize college students’ alcohol consumption. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:30–40. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls TA, Fairlie AM, Wood MD. Parents do matter: A longitudinal two-part mixed model of early college alcohol participation and intensity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:908–918. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4(2):98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q. Reconsidering baron and kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37:197–206. [Google Scholar]