Abstract

To assess the clinical efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee (KOA), a systematic electronic literature search was performed on PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science. Studies published in English from the earliest record to December 2014 were searched using the following keywords: Cartilage defect, cartilage repair, osteoarthritis, KOA, stem cells, MSCs, bone marrow concentrate (BMC), adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, synovial-derived mesenchymal stem cells and peripheral blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells. The effect sizes of selected studies were determined by extracting pain scores from the visual analog scale and functional changes from International Knee Documentation Committee and Lysholm and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index before and after MSCs or reference treatments at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. The factors were analyzed and the outcomes were modified after comparing the MSC group pooled values with the pretreatment baseline or between different treatment arms. A systematic search identified 18 clinical trials on this topic, including 10 single-arm prospective studies, four quasi-experimental studies and four randomized controlled trials that used BMCs to treat 565 patients with KOA in total. MSC treatment in patients with KOA showed continual efficacy for 24 months compared with their pretreatment condition. Effectiveness of MSCs was improved at 12 and 24 months post-treatment, compared with at 3 and 6 months. No dose-responsive association in the MSCs numbers was demonstrated. However, patients with arthroscopic debridement, activation agent or lower degrees of Kellgren-Lawrence grade achieved improved outcomes. MSC application ameliorated the overall outcomes of patients with KOA, including pain relief and functional improvement from basal evaluations, particularly at 12 and 24 months after follow-up.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cells, knee, osteoarthritis, articular cartilage, stem cell therapy, meta-analysis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic, progressive and degenerative joint disease, involving single or multiple joints. OA of the knee (KOA) is the most common disabling disease, characterized by the degeneration and degradation of cartilage, subchondral bone remodeling, osteophyte formation and synovial inflammation, which affects the patient's quality of life and constitutes a heavy financial burden (1–3). With the exception of oral and intra-article injection medications that relieve the symptoms and improve joint function, there is no approved medical treatment that halts disease progression and joint destruction (1,4).

Various surgical methods, including microfracture (5,6) and subchondral drilling (7), have been proposed to regenerate articular cartilage. However, due to the complications and inferior quality of the regenerative fibrocartilage, risky and cost-effective joint replacement surgery is often ultimately required (8). Previous studies have investigated tissue engineering and cellular therapies for treating early stage OA, and autologous chondrocyte implantation has demonstrated positive clinical outcomes (9,10). Nevertheless, due to the poor self-renewal and regeneration potential of chondrocytes, it is a slow process that may lead to fibrocartilage rather than hyaline cartilage (11,12). Furthermore, this two-stage surgical procedure and is predominantly used to treat cartilage defects caused by injury rather than OA.

Therefore, research attention in this field has shifted to the more promising treatment of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). MSCs, which can be derived from blood, bone marrow, skeletal muscle, adipose, skin and synovial membrane (13), have the capacity to differentiate into osteocytes, adipocytes, chondrocytes, myoblasts, tenocytes (14,15), secrete bioactive molecules that stimulate angiogenesis and tissue repair, and reduce the response of T cells and inflammation (16,17). Previous clinical trials have reported that mild/moderate OA or advanced OA can be treated efficiently using autologous or allogenic MSCs through implantation, micro fracture or intra-articular injections (18–20). However, so far, no meta-analytic research has evaluated the efficacy and safety of MSCs in treating patients with KOA.

Therefore, the present meta-analysis was conducted to analyze the clinical outcomes of MSC treatment on patients with KOA patients by analyzing pain and functional changes, compared with their pretreatment condition, or placebo controls.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

Electronic databases: including PubMed (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), EMBASE (embase.com) and Web of Science (webofknowledge.com), were used to comprehensively search for all relevant studies published in English from the earliest record to December 2014. The following keywords were used: ‘cartilage defect’, ‘cartilage repair’, ‘osteoarthritis’, ‘knee osteoarthritis’, ‘stem cells’, ‘mesenchymal stem cells’ (MSCs), ‘bone marrow concentrate’, ‘adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells’ (ADMSCs), ‘synovial-derived mesenchymal stem cells’ and ‘peripheral blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells’, as medical subject headings or text words. In addition, Cochrane Systematic Reviews (cochrane.org/evidence) and ClinicalTrials.gov were manually searched for additional references. Articles were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: i) Patients were ≥18 years-old and had KOA symptom or diagnosed with KOA by clinical and imaging examination; ii) MSCs administered to at least one treatment group; iii) ≥3-month follow-up; iv) ≥1 valid outcome measurement before and after the administration of MSCs, such as the visual analogue scale (VAS), International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Form, Lysholm scale, and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC); and v) outcomes were presented as continuous data [mean ± standard deviation (SD)]. Studies that lacked an intervention plan or pain and functional measurements were excluded.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

Two independent reviewers searched the electronic databases and evaluated the eligibility of the searched articles and subsequently extracted data using a standardized form, including data on the study type, number of patients enrolled, patient characteristics, disease duration, dosage of MSCs, outcome measurements, follow-up time and adverse events. If additional data was necessary, the authors were contacted for further information. The Jadad scoring system was used to assess the methodological quality of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (21). The quality of the included RCTs ranged from 0–5 points, with a score of <3 indicating a low-quality study. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of other studies according to selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome, including single-arm prospective and quasi-experimental studies (22). NOS was scored out of 9 points, with total scores <4 points defined as low quality. Discrepancies between the two independent evaluations of potential articles were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Data synthesis and analysis

Data were extracted from four time points at or closest to the 3rd, 6th, 12th and 24th months after MSCs treatment. Effect size (ES) was calculated from knee joint pain and functional changes and the results were compared with the pretreatment baseline or between different treatment arms. VAS was extracted from the included articles. If >1 functional measurement was included in an article, only one functional scale in line with the order of IKDC, Lysholm and WOMAC was chosen. As multiple treatment groups wew included in some articles, each group was selected as a separate status set to analysis. Mean ± SD between the pretreatment baseline condition and functional scores after treatment was used to evaluate the effectiveness of MSCs therapy. Positive ES values demonstrated a pain or functional improvement, and vice versa. For studies in which the measurement score and SD was deficient, the value was calculated from the P-value of the corresponding hypothesis test. If the measurement scores and SD could not be extracted in some articles, a correlation of 0.5 was used to estimate the dispersion. A random effect model was used to pool the ESs with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI) on the basis of heterogeneity. A positive pooled ES with a 95%CI >0 indicated an advantage of MSCs compared with the pretreatment condition or reference treatments.

Assessment of heterogeneity and sensitivity

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed via the I-square and Cochran's Q tests. A P-value of <0.10 for χ2 test or an I-square >50% was indicative of the existence of substantial heterogeneity (21). Subgroup analysis was performed according to variables of the study design, different dosages, arthroscopic debridement (AD), activation agent, as well as the severity of Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) grades. Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding some articles with extreme ES values to assess whether the movement resulted in serious changes in the total result. Funnel plots were used to assess the potential publication bias. All analyses were conducted using Review Manager Version 5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Results

Study characteristics

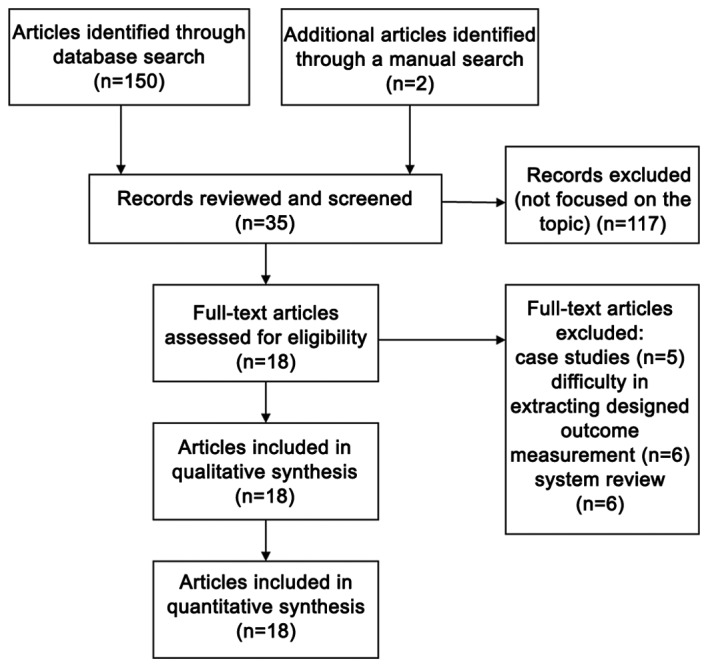

A total of 152 studies were initially searched, of which 117 were removed after title and abstract screening. Of the 35 citations, 18 clinical studies which met the inclusion criteria were identified for eligibility (Fig. 1); five case studies (17,22–26) were excluded and nine studies (24,27–34) were removed due to difficulties in extracting the outcome measurements. Four systematic reviews (35–38) were also excluded. An assessment of the remaining 18 studies revealed that 10 used a single-arm prospective design (18–20,39–45), four used quasi-experimental trials (46–49) and four used RCT (50–53) (Table I). A total of 565 participants (226 males and 339 females) were included from the 18 studies. The duration from the onset of knee pain to registration in each study was 3 months to ≥7 years. The follow-up period was 3–24 months. The majority of studies recruited patients with KOA with a severity grade of 1–4 on the K-L scale. K-L grade s 1–2, and grades 3–4 were defined as early OA and advanced OA, respectively (Table II).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the evaluation process for the inclusion or exclusion of studies.

Table I.

Summary of studies using MSCs to treat KOA patients.

| Author, year | Number of patients | Mean age (year) | BMI | Disease duration | Double blind | ITT | Outcome measure | Follow-up time (month) | Adverse events | Quality assessment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-arm, prospective follow-up studies | |||||||||||

| Buda et al, 2010 | 20 (12M, 8F) | NM | NM | ≥12 months | No | Yes | IKDC | 6, 12, 24 | None | 4a | (39) |

| Gobbi et al, 2011 | 15 (10M, 5F) | 48 (32–58) | 24.5±2.53 | NM | No | Yes | VAS, IKDC | 6, 12, 24 | None | 4a | (40) |

| Davatchi et al, 2011 | 4 (2M, 2F) | 57.7±5.0 | 30.25±4.86 | ≥7 years | No | Yes | VAS | 6 | None | 4a | (18) |

| Emadedin et al, 2012 | 6 (6F) | 53.8±8.9 | 31.6±4.2 | NM | No | Yes | VAS, WOMAC | 2, 6, 12 | None | 4a | (19) |

| Koh et al, 2013 | 18 (6M, 12F) | 54.6±7.8 | NM | ≥6 months | No | No | VAS, Lysholm | 24 | Marked pain in 1 patient | 4a | (20) |

| Turajane et al, 2013 | 5 (1M, 4F) | 57.2±1.92 | 25.36±4.46 | ≥3 months | No | Yes | VAS, WOMAC | 1,6 | None | 4a | (41) |

| Orozco et al, 2013 | 12 (6M, 6F) | 49±17.3 | NM | ≥6 months | No | Yes | VAS, WOMAC | 3, 6, 12, 24 | Local pain with discomfort in 6 patients | 4a | (42) |

| Author, year | Number of patients | Average age (year) | BMI | Disease duration | Double blind | ITT | Outcome measure | Follow-up time (month) | Adverse event | Quality assessment | Ref. |

| Kim et al, 2014 | 41 (17M, 24F) | 60.7 (53–80) | <30 | ≥12 months | No | Yes | VAS, IKDC | 3, 6, 12 | Joint swelling in 69 knees, pain in 31 knees | 4a | (43) |

| Koh et al, 2013 | 30 (5M, 25F) | 70.3 (65–80) | NM | ≥12 months | No | Yes | VAS, Lysholm | 3, 12, 24 | Slight pain in 3 patients | 4a | (44) |

| Gobbi et al, 2014 | 25 (16M, 5F) | 46.5±8.55 | 24.4±3.0 | ≥3 years | No | Yes | VAS, IKDC | 12, 24 | None | 4* | (45) |

| Quasi-experimental studies | |||||||||||

| Koh and Choi, 2012 | 50 (MSCs + PRP group: 8M, 17F; PRP group: 8M; 17F) | MSC group: 54.2±9.3; placebo group: 54.4±11.3 | NM | ≥12 months | No | Yes | VAS, Lysholm | 3, 12 | Marked pain with swelling in 1 patient | 5a | (46) |

| Koh et al, 2014 | 56 (Group 1: 8M, 13F; Group 2: 14M, 21F) | Group 1: 55.3±4.1; Group 2: 57.4±5.7 | Group 1: 26.7±3.1; Group 2: 26.3±3.0 | ≥12 months | No | No | IKDS | 12, 24 | None | 5a | (47) |

| Jo et al, 2014 | 18 (LDG: 1M, 2F; MDG: 0M, 3F; HDG: 2M, 10F) | LDG: 63±8.6 MDG: 65±6.6 HDG: 61±6.2 | LDG: 26±1.0 MDG: 28±2.1 HDG: 26±2.1 | ≥4 months | No | Yes | VAS, WOMAC | 3, 6 | Mild (LDG:3; MDG: 2; HDG:5) | 5a | (48) |

| Kim et al, 2014 | 54 (MSCs group: 14M, 23F; MSC + fibrin glue group: 8M, 9F) | MSCs group: 57.5±5.9; MSC + fibrin glue group: 57.7±5.8 | MSCs group: 26.3±3.2; MSC + fibrin glue group: 27.3±2.9 | ≥18 months | No | No | IKDC | 12, 24 | None | 5a | (49) |

| Randomized controlled trials | |||||||||||

| Varma et al, 2010 | 50 (AD: 25; AD + MSC: 25) | AD group: 48.20±5.13; AD + MSC: 50.67±5.38 | NM | NM | No | Yes | VAS | 3, 6 | None | 3b | (50) |

| Saw et al, 2013 | 50 (HAG: 7M, 17F; HA + PBSC group 10M, 15F) | HAG: 42±5.91 HA + PBSC: 38±7.33 | HA: 24.83±4.04 HA + PBSC: 24.91±4.15 | ≥12 months | No | No | IKDS | 6, 12, 24 | None | 3b | (51) |

| Wong et al, 2013 | 56 (HTO + MSC: 15M, 13F HTO: 14M, 14F) | HTO + MSC: 53 (36–54) HTO: 49 (24–54) | HTO + MSC: 23.81±2.17 HTO: 23.89±3.20 | NM | No | Yes | IKDS, Tegner, Lysholm | 6, 12, 24 | None | 3b | (52) |

| Vangsness et al, 2014 | 55 (LDG: 11M, 7F; HDG: 14M, 4F HAG: 13M, 6F) | LDG: 44.6±9.82 HDG: 45.6±12.42 HAG: 47.8±8 | LDG: 29.86±7.94; HDG: 29.09±5.91; HAG: 26.89± 4.05 | NM | Yes | No | VAS, Lysholm | 6, 12, 24 | Mild (LDG:18; HDG: 17; HAG: 17) | 5b | (53) |

MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; M, male; F, female; BMI, body mass index; ITT, intention-to-treat; HAG, hyaluronic acid group; PBSCs, peripheral blood stem cells; HTO, high tibial osteotomy; VAS, the visual analog scale; IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Quality scores derived from the Newcastle-Ottawa scale

quality scores derived from the Jadad scale; NM, not mentioned; LDG, low-dose group; MDG, mid-dose group; HDG, high-dose group; AD, arthroscopic debridement.

Table II.

Summary of the preparations and injection details of MSCs in the retrieved trials.

| Author, year | MSC origin | Number of cells | Delivery system | Method of implementation | Activation agent | K-L grade | Comparison | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-arm, prospective follow-up studies | ||||||||

| Buda et al, 2010 | Autologous BMAC | NM | AD | Implantation | HA, membrane scaffold | NM | None | (39) |

| Gobbi et al, 2011 | Autologous BMAC | NM | Mini-arthrotomy | Implantation | Collagen matrix | NM | None | (40) |

| Davatchi et al, 2011 | Autologous BMSCs | 8–9×106 | None | Intra-articular injection | None | 3–4 | None | (18) |

| Emadedin et al, 2012 | Autologous BMSCs | 2.0–2.4×107 | None | Intra-articular injection | None | 4 | None | (19) |

| Koh et al, 2013 | Autologous AMSCs | 1.18×106 | AD, synovectomy | Intra-articular injection | PRP | 3–4 | None | (20) |

| Turajane et al, 2013 | Autologous BSC | NM | Microfracture | Intra-articular injection | GFAP, HA | 2 | None | (41) |

| Orozco et al, 2013 | Autologous BMSCs | 40×106 | None | Intra-articular injection | None | 2–4 | None | (42) |

| Kim et al, 2014 | Autologous BMSCs | 2.4×105 | Microfracture and AD | Intra-articular injection | Adipose tissues | 1–4 | None | (43) |

| Koh et al, 2013 | Autologous AMSCs | 4.04×106 | Arthroscopic lavage | Intra-articular injection | None | 2–4 | None | (44) |

| Gobbi et al, 2014 | Autologous BMAC | NM | AD | Implantation | Collagen cell sheets | NM | None | (45) |

| Quasi-experimental studies | ||||||||

| Koh and Choi, 2012 | Autologous AMSCs | 1.89×106 | AD, synovectomy | Intra-articular injection | PRP | 3 | MSCs + PRP vs. PRP | (46) |

| Koh et al, 2014 | Autologous AMSCs | 3.8×106 | AD | Implantation | None | 1–2 | None | (47) |

| Jo et al, 2014 | Autologous AMSCs | LDG: 1×107 MDG: 5×107 HDG:10×107 | None | Intra-articular injection | None | 3–4 | None | (48) |

| Kim et al, 2014 | Autologous AMSCs | 3.9×106 | AD | Implantation | Fibrin glue | 1–2 | MSCs vs. MSCs + fibrin glue | (49) |

| Randomized controlled trials | ||||||||

| Varma et al, 2010 | Buffy coat | Not mentioned | None | Intra-articular injection | None | 1–2 | None | (50) |

| Author, year | Number Origin of MSCs | of cells | Implementation Delivery system | method | Activation agent | K-L grade | Comparison | Ref. |

| Saw et al, 2013 | Autologous PBSCs | NM | Microfracture injection | Intra-articular | None HA + PBSC group | NM | HA group vs. | (51) |

| Wang et al, 2013 | Autologous BMAC | 1.46×107 | HTO injection | Intra-articular | HA vs. HTO group | NM | HTO + MSCs group | (52) |

| Vangsness et al, 2014 | Allogenic BMSCs | 5.0×107,15×107 meniscectomy | Partial medial | Intra-articular injection | None | NM | Group A: LD MSCs + HA Group B: HD MSCs + HA; control group: HA | (53) |

Effects of MSCs

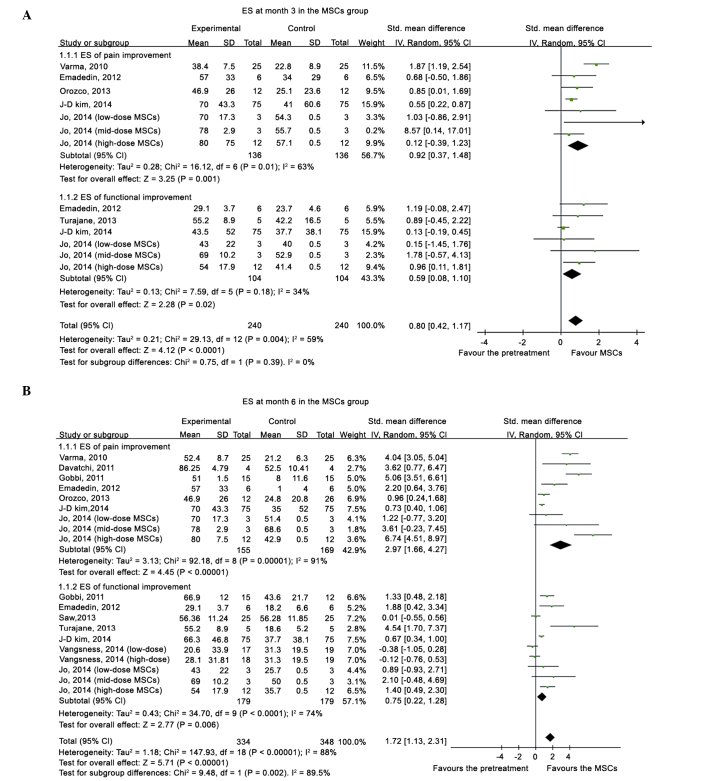

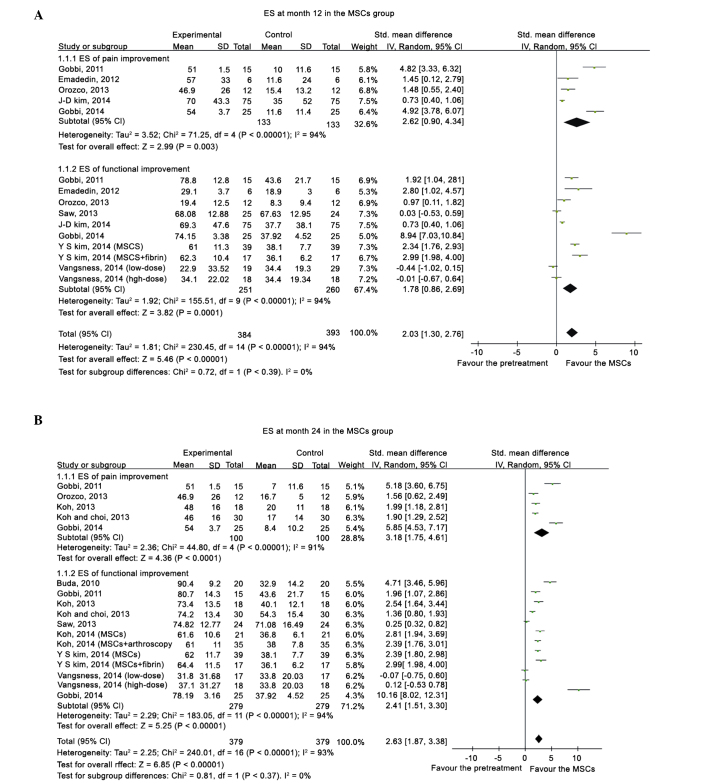

Compared with the pretreatment condition, a pooled ES of 0.80 (95%CI, 0.42–1.17) was determined at 3 months, 1.72 (95%CI, 1.13–2.31) at 6 months, 2.03 (95%CI, 1.30–2.76) at 12 months (Fig.2), and 1.81 (95%CI, 1.62–2.00) at 24 months (Fig. 3), which all favored the status after MSCs treatment. Following the exclusion of an outlier with an extremely high ES, the beneficial effects from MSCs treatment remained, with an ES of 0.77 (95%CI, 0.41–1.13) at 3 months, 1.49 (95%CI, 0.93–2.04) at 6 months, 1.63 (95%CI, 0.99–2.27) at 12 months, and 1.74 (95%CI, 1.55–1.93) at 24 months. A significant superiority of MSCs intervention was demonstrated by a high summed ES at 12 and 24 months without an overlap of the 95%CI of ES at 3 months, which indicated that the treatment effect of MSCs on KOA patients improved significantly over time. However, after excluding the data from quai-experimental and single-arm prospective studies and only using the data from RCTs, the treatment of MSCs did not demonstrate superiority. Relative to the baseline, patients improved in the pain and functional scale scores at all time points.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of ES of pain and functional changes from baseline at (A) 3 and (B) 6 months after MSC treatment. ES, effect size; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of ES of pain and functional changes from baseline at (A) 12 and (B) 24 months after MSC treatment. ES, effect size; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Stratified analysis

Participants receiving MSC treatment were stratified according to the study design, administration dosage, AD, activation agents and K-L grades. Point estimates of the pooled ES in the single-arm prospective studies and quasi-experimental trials were higher than those in the RCTs, and an uncertainty in the treatment effectiveness emerged regarding participants in the RCTs at 6, 12 and 24 months, since the 95%CI of the summed ES crossed the value of 0. Stratified analysis failed to demonstrate a dose-responsiveness association in the MSC numbers. However, the treatment effectiveness in the MSC groups with AD or activation agents was superior to the MSC groups without AD and activation agents, particularly at 12 months in the activation agents group (ES, 3.13; 95%CI, 1.55–4.71) compared with the group without activation agents (ES, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.01–1.34). And the early OA group exhibited a higher ES point estimate at all time points than the advanced OA group (Table III).

Table III.

Analysis of the effect sizes of MSC treatment stratified by the indicated subgroups.

| Subgroup | Pooled effect size at month 3 | Pooled effect size at month 6 | Pooled effect size at month 12 | Pooled effect size at month 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||||

| Single-arm follow-up study | 0.48 (0.18–0.77) | 1.48 (0.51–2.44) | 2.66 (1.69–3.62) | 2.87 (1.99–3.75) |

| Quasi-experimental study | 0.75 (0.17–1.32) | 1.37 (0.59–2.14) | 2.53 (1.96–3.10) | 2.53 (2.18–2.89) |

| Randomized controlled trial | 1.87 (1.19–2.54) | 1.09 (−0.35–2.53) | 0.14 (0.49–0.20) | 0.12 (0.24–0.48) |

| MSCs doses administered | ||||

| <5×106 | 0.34 (−0.08–0.75) | 0.70 (0.46–0.93) | 1.60 (0.73–2.46) | 2.25 (1.54–2.97) |

| 5×106-5×107 | 0.89 (0.36–1.42) | 1.39 (0.80–1.99) | 1.60 (0.55–2.65) | −0.07 (−0.75–0.60) |

| >1×107 | 0.67 (0.09–1.26) | 1.91 (0.58–3.23) | −0.01 (−0.67–0.64) | 0.12 (−0.53–0.78) |

| Arthroscopic debridement | ||||

| Yes | 0.37 (0.01–0.74) | 0.45 (−0.16–1.06) | 2.20 (1.30–3.09) | 2.32 (1.61–3.03) |

| No | 1.02 (0.58–1.47) | 1.48 (0.80–2.16) | 1.41 (0.83–2.00) | 1.56 (0.62–2.49) |

| Activation agent | ||||

| Yes | 0.37 (0.01–0.74) | 1.40 (0.26–2.54) | 3.13 (1.55–4.71) | 2.82 (2.07–3.56) |

| No | 1.02 (0.58–1.47) | 1.29 (0.53–2.05) | 0.67 (0.01–1.34) | 0.84 (0.16–1.52) |

| Severity of degeneration | ||||

| Early OA | 1.55 (0.66–2.45) | 4.10 (3.16–5.04) | 2.53 (1.96–3.10) | 2.53 (2.18–2.89) |

| Advanced OA | 0.78 (0.34–1.22) | 2.40 (1.34–3.46) | 1.99 (0.70–3.28) | 2.54 (1.64–3.44) |

Values are expressed by their point estimates with a 95% CI. 95% CI covered a zero value, which indicated an uncertainty of treatment effectiveness compared with the pretreatment baseline. MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; OA, osteoarthritis; CI, confidence interval.

Adverse effects and publication bias

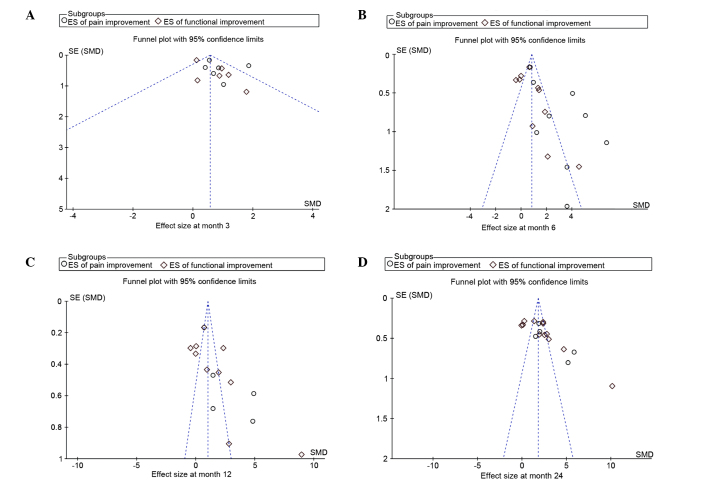

Seven of the 18 trials reported adverse events after MSC treatment, in which the predominant symptoms were local swelling and transient regional pain. All of the adverse events reported by patients were self-limited or were remedied with therapeutic measures. None of the patients included in the present study were diagnosed with cancer that was associated with MSC therapy. Asymmetry was observed in the funnel plots based on the ESs of changes in the pain and functional scales from baseline (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Funnel plots of the ES of pain and functional changes from baseline at (A) 3, (B) 6, (C) 12 and (D) 24 months post-MSC treatment. ES, effect size; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; SE, standard error; SMD, standard mean difference.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis comparing the conditions of patients with KOA before and after treatment with MSCs demonstrated a continual efficacy for at least 24 months. Following analysis of the pooled ESs at 12 and 24 months, these values were higher than the summed ESs at 3 months, which indicated that the treatment effect of MSCs did not decrease in a time-dependent manner. However, a dose-responsiveness association was not demonstrated in the MSC numbers. The treatment effectiveness in the MSC groups treated with AD or activation agents was superior to the MSCs groups alone. Notably, the early OA group exhibited a higher ES point estimate at all time points, as compared with the advanced OA group.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous meta-analytic research has quantified the effectiveness of MSC treatment and analyzed the factors and modified the outcomes. Several reviews of the literature (35–38) have analyzed the role of MSCs therapy in KOA. Barry and Murphy (37) stressed that paracrine factor must be used as a measure to evaluate the potential treatment of MSCs in order to replace traditional measures based on differentiation and cell-surface markers. They also outlined that early-stage clinical trials are underway for test the method of intra-articular injection of MSCs into the knee. However, the optimal dose and vehicle have not been established. Filardo et al (38) reported that, due to the prevalence of low-quality preclinical studies and clinical trials, knowledge on the treatment of MSCs for cartilage regeneration remains preliminary, despite the growing interest in the biological approach. Rodriguez-Merchan (35) highlighted the efficacy of utilizing intra-articular injections of MSCs to treat KOA; however, the results of the treatment are simply encouraging. Kristjansson and Honsawek (36) discussed and assessed three ways in which MSCs may be used to treat OA patients by intra-articular injections and implantation as well as micro fracture. They reported that with higher numbers of MSCs injected superior results would be obtained. However, in order to facilitate the treatment, a single injection of MSCs alone or in combination of growth factors would be the ultimate solution.

The present meta-analysis suggested that MSC treatment significantly improved pain and functional status, relative to the basal evaluations in KOA, and the beneficial effect was maintained for two years after treatment. Furthermore, the treatment effectiveness did not reduce over time. Several factors mentioned by anecdotal research may modify the ESs of MSC treatment. In terms of the study design, the pooled ESs in single-arm and quasi-experimental studies were likely to be higher than those in RCTs. However, the results of these RCT studies suggested that MSCs also reduce pain and improve function in patients with KOA. Regarding the number of MSCs used in treatment, a dose-responsiveness relationship remained unclear. Jo et al (48) enrolled 18 patients who were injected with ADMSCs into the knee. The study consisted of three groups, the low-dose (1.0×107 cells), mid-dose (5.0×107), and high-dose (1.0×108) groups. However, a significant improvement in joint function and reduction in pain was observed in the low and mid-dose groups. Conversely, in previous studies, an increased number of cells yielded superior results. Therefore, the optimal dose and vehicle are yet to be established. One potential modifier is the AD. The present stratified analysis suggested that AD potentially contributed to an increase in treatment effectiveness. Another issue is the addition of activation agents, particularly at 12 months in the activation agents group (ES, 3.13; 95% CI, 1.55–4.71) compared with the group without activation agents (ES, 0.67; 95%CI, 0.01–1.34). The present subgroup analysis showed that the efficacy varied according to the degenerative severity, which was associated with the regenerative potential of damaged cartilage. These results are compatible with the findings of the majority of previous trials, and the early OA group exhibited a higher ES point estimated at all time points than the advanced OA group.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81160225, 81260453 and 81360451) and the Xinjiang Bingtuan Special Program of Medical Science (grant nos. 2014CC002, 2013BA020 and 2012BC002).

References

- 1.Findlay DM. If good things come from above, do bad things come from below? Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:119. doi: 10.1186/ar3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Articular cartilage and subchondral bone in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1192:230–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross JB, Guillaume C, Gégout-Pottie P, Mainard D, Presle N. Synovial fluid levels of adipokines in osteoarthritis: Association with local factors of inflammation and cartilage maintenance. Biomed Mater Eng. 2014;24(Suppl 1):S17–S25. doi: 10.3233/BME-140970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawker GA, Mian S, Bednis K, Stanaitis I. Osteoarthritis year 2010 in review: Non-pharmacologic therapy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakata K, Furumatsu T, Abe N, Miyazawa S, Sakoma Y, Ozaki T. Histological analysis of failed cartilage repair after marrow stimulation for the treatment of large cartilage defect in medial compartmental osteoarthritis of the knee. Acta Med Okayama. 2013;67:65–74. doi: 10.18926/AMO/49259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee GW, Son JH, Kim JD, Jung GH. Is platelet-rich plasma able to enhance the results of arthroscopic microfracture in early osteoarthritis and cartilage lesion over 40 years of age? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013;23:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s00590-012-1038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eldracher M, Orth P, Cucchiarini M, Pape D, Madry H. Small subchondral drill holes improve marrow stimulation of articular cartilage defects. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2741–2750. doi: 10.1177/0363546514547029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowsey MM, Gunn J, Choong PF. Selecting those to refer for joint replacement: Who will likely benefit and who will not? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knutsen G, Drogset JO, Engebretsen L, Grøntvedt T, Isaksen V, Ludvigsen TC, Roberts S, Solheim E, Strand T, Johansen O. A randomized trial comparing autologous chondrocyte implantation with microfracture. Findings at five years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2105–2112. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CR, Grodzinsky AJ, Hsu HP, Martin SD, Spector M. Effects of harvest and selected cartilage repair procedures on the physical and biochemical properties of articular cartilage in the canine knee. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:790–799. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasiliadis HS, Wasiak J. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for full thickness articular cartilage defects of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD003323. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003323.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandelbaum B, Browne JE, Fu F, Micheli LJ, Moseley JB, Jr, Erggelet C, Anderson AF. Treatment outcomes of autologous chondrocyte implantation for full-thickness articular cartilage defects of the trochlea. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:915–921. doi: 10.1177/0363546507299528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise review: Mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: The state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair-current views. Stem cells. 2007;25:2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delorme B, Ringe J, Pontikoglou C, Gaillard J, Langonné A, Sensebé L, Noël D, Jorgensen C, Häupl T, Charbord P. Specific lineage-priming of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells provides the molecular framework for their plasticity. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1142–1151. doi: 10.1002/stem.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oreffo RO, Cooper C, Mason C, Clements M. Mesenchymal stem cells: Lineage, plasticity and skeletal therapeutic potential. Stem Cell Rev. 2005;1:169–178. doi: 10.1385/SCR:1:2:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robey PG, Bianco P. The use of adult stem cells in rebuilding the human face. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:961–972. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caplan AI. Why are MSCs therapeutic? New data: New insight. J Pathol. 2009;217:318–324. doi: 10.1002/path.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davatchi F, Abdollahi B Sadeghi, Mohyeddin M, Nikbin B. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis: 5 years follow-up of three patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emadedin M, Aghdami N, Taghiyar L, Fazeli R, Moghadasali R, Jahangir S, Farjad R, Eslaminejad M Baghaban. Intra-articular injection of autologous mesenchymal stem cells in six patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:422–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh YG, Jo SB, Kwon OR, Suh DS, Lee SW, Park SH, Choi YJ. Mesenchymal stem cell injections improve symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroda R, Ishida K, Matsumoto T, Akisue T, Fujioka H, Mizuno K, Ohgushi H, Wakitani S, Kurosaka M. Treatment of a full-thickness articular cartilage defect in the femoral condyle of an athlete with autologous bone-marrow stromal cells. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakitani S, Nawata M, Tensho K, Okabe T, Machida H, Ohgushi H. Repair of articular cartilage defects in the patello-femoral joint with autologous bone marrow mesenchymal cell transplantation: Three case reports involving nine defects in five knees. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2007;1:74–79. doi: 10.1002/term.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centeno CJ, Busse D, Kisiday J, Keohan C, Freeman M, Karli D. Increased knee cartilage volume in degenerative joint disease using percutaneously implanted, autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Pain Physician. 2008;11:343–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centeno CJ, Busse D, Kisiday J, Keohan C, Freeman M, Karli D. Regeneration of meniscus cartilage in a knee treated with percutaneously implanted autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:900–908. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wakitani S, Mitsuoka T, Nakamura N, Toritsuka Y, Nakamura Y, Horibe S. Autologous bone marrow stromal cell transplantation for repair of full-thickness articular cartilage defects in human patellae: Two case reports. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:595–600. doi: 10.3727/000000004783983747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakitani S, Imoto K, Yamamoto T, Saito M, Murata N, Yoneda M. Human autologous culture expanded bone marrow mesenchymal cell transplantation for repair of cartilage defects in osteoarthritic knees. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:199–206. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nejadnik H, Hui JH, Choong EP Feng, Tai BC, Lee EH. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells versus autologous chondrocyte implantation: An observational cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1110–1116. doi: 10.1177/0363546509359067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakitani S, Okabe T, Horibe S, Mitsuoka T, Saito M, Koyama T, Nawata M, Tensho K, Kato H, Uematsu K. Safety of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for cartilage repair in 41 patients with 45 joints followed for up to 11 years and 5 months. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5:146–150. doi: 10.1002/term.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saw KY, Anz A, Merican S, Tay YG, Ragavanaidu K, Jee CS, McGuire DA. Articular cartilage regeneration with autologous peripheral blood progenitor cells and hyaluronic acid after arthroscopic subchondral drilling: A report of 5 cases with histology. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser RA, Orlofsky A. Regenerative injection therapy with whole bone marrow aspirate for degenerative joint disease: A case series. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;6:65–72. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S10951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orozco L, Munar A, Soler R, Alberca M, Soler F, Huguet M, Sentís J, Sánchez A, García-Sancho J. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with autologous mesenchymal stem cells: Two-year follow-up results. Transplantation. 2014;97:e66–e68. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centeno CJ, Schultz JR, Cheever M, Freeman M, Faulkner S, Robinson B, Hanson R. Safety and complications reporting update on the re-implantation of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells using autologous platelet lysate technique. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2011;6:368–378. doi: 10.2174/157488811797904371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centeno CJ, Schultz JR, Cheever M, Robinson B, Freeman M, Marasco W. Safety and complications reporting on the re-implantation of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells using autologous platelet lysate technique. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;5:81–93. doi: 10.2174/157488810790442796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Merchán EC. Intra-articular injections of mesenchymal stem cells for knee osteoarthritis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2014;43:E282–E291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kristjnsson B, Honsawek S. Current perspectives in mesenchymal stem cell therapies for osteoarthritis. Stem Cells Int. 2014;2014:194318. doi: 10.1155/2014/194318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barry F, Murphy M. Mesenchymal stem cells in joint disease and repair. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:584–594. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Filardo G, Madry H, Jelic M, Roffi A, Cucchiarini M, Kon E. Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of cartilage lesions: From preclinical findings to clinical application in orthopaedics. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1717–1729. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buda R, Vannini F, Cavallo M, Grigolo B, Cenacchi A, Giannini S. Osteochondral lesions of the knee: A new one-step repair technique with bone-marrow-derived cells. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(Suppl 2):S2–S11. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Scotti C, Mahajan V, Mazzucco L, Grigolo B. One-step cartilage repair with bone marrow aspirate concentrated cells and collagen matrix in full-thickness knee cartilage lesions: Results at 2 year follow-up. Cartilage. 2011;2:286–299. doi: 10.1177/1947603510392023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turajane T, Chaweewannakorn U, Larbpaiboonpong V, Aojanepong J, Thitiset T, Honsawek S, Fongsarun J, Papadopoulos KI. Combination of intra-articular autologous activated peripheral blood stem cells with growth factor addition/ preservation and hyaluronic acid in conjunction with arthroscopic microdrilling mesenchymal cell stimulation improves quality of life and regenerates articular cartilage in early osteoarthritic knee disease. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96:580–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orozco L, Munar A, Soler R, Alberca M, Soler F, Huguet M, Sentís J, Sánchez A, García-Sancho J. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with autologous mesenchymal stem cells: A pilot study. Transplantation. 2013;95:1535–1541. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318291a2da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JD, Lee GW, Jung GH, Kim CK, Kim T, Park JH, Cha SS, You YB. Clinical outcome of autologous bone marrow aspirates concentrate (BMAC) injection in degenerative arthritis of the knee. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24:1505–1511. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koh YG, Choi YJ, Kwon SK, Kim YS, Yeo JE. Clinical results and second-look arthroscopic findings after treatment with adipose-derived stem cells for knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:1308–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Sankineani SR. One-step surgery with multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large full-thickness chondral defects of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:648–657. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koh YG, Choi YJ. Infrapatellar fat pad-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2012;19:902–907. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koh YG, Choi YJ, Kwon OR, Kim YS. Second-look arthroscopic evaluation of cartilage lesions after mesenchymal stem cell implantation in osteoarthritic knees. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1628–1637. doi: 10.1177/0363546514529641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jo CH, Lee YG, Shin WH, Kim H, Chai JW, Jeong EC, Kim JE, Shim H, Shin JS, Shin IS, et al. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: A proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1254–1266. doi: 10.1002/stem.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim YS, Choi YJ, Suh DS, Heo DB, Kim YI, Ryu JS, Koh YG. Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in osteoarthritic knees: Is fibrin glue effective as a scaffold? Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:176–185. doi: 10.1177/0363546514554190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varma HS, Dadarya B, Vidyarthi A. The new avenues in the management of osteo-arthritis of knee-stem cells. J Indian Med Assoc. 2010;108:583–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saw KY, Anz A, Siew-Yoke JC, Merican S, Ching-Soong Ng R, Roohi SA, Ragavanaidu K. Articular cartilage regeneration with autologous peripheral blood stem cells versus hyaluronic acid: A randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong KL, Lee KB, Tai BC, Law P, Lee EH, Hui JH. Injectable cultured bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in varus knees with cartilage defects undergoing high tibial osteotomy: A prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years' follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:2020–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vangsness CT, Jr, Farr J, II, Boyd J, Dellaero DT, Mills CR, LeRoux-Williams M. Adult human mesenchymal stem cells delivered via intra-articular injection to the knee following partial medial meniscectomy: A randomized, double-blind, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:90–98. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]