Abstract

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-associated mortality globally. Interactions of the cancer cells with the tumor microenvironment are essential carcinogenic features for the majority of solid tumors, such as pancreatic cancer. The present study investigated the role of stromal activation in NSCLC and analyzed the surgical specimens of 93 patients by immunohistochemistry with regard to periostin (an extracellular matrix protein), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; a marker of myofibroblasts) and cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31; a marker of endothelial cells), and the activated stroma index. There was a trend towards reduced overall survival for patients with high periostin expression (hazard ratio, 1.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.99–3.27; P=0.050). No significant correlations with overall survival were identified for α-SMA (P=0.930), CD31 (P=0.923), collagen (P=0.441) or the activated stroma index (P=0.706). In a multivariable analysis, the histological tumor subtype, tumor stage, lymph node involvement and resection status were independent prognostic factors in NSCLC, but none of the investigated immunohistochemical markers were prognostic factors. Thus, the tumor microenvironment and stroma activation did not prove to be of prognostic relevance for lung cancer, as it has been previously described for pancreatic cancer. Other markers of the microenvironment of NSCLC may be of higher prognostic value, pointing towards tumor-type specific effects.

Keywords: stroma, lung cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, microenvironment, periostin

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the leading cancer types worldwide with regard to incidence and mortality rates (1). The two major forms are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with 85% of of all newly diagnosed lung cancers, and small cell lung cancer, with 15% (2). NSCLC is further divided into four subtypes: Adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma, large cell carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma. The majority of patients are diagnosed at an advanced tumor stage and are therefore not candidates for curative surgical resection. These patients receive multimodal chemotherapy, with or without radiation (3). Despite all efforts, the overall 5-year survival rate of NSCLC patients is only ~15% (1,4,5). Due to the poor prognosis of NSCLC, current research aims to improve our understanding of the biological and molecular genetic background of the disease in order to identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Tumor growth is not only determined by the neoplastic cells themselves, but also, depending on the tumor entity, more or less by the stroma compartment. In carcinomas, the desmoplastic stroma reaction is a consistent histological feature; however, the prognostic role of the stroma in NSCLC is not as clear as it is in other tumor entities (6). The tumor stroma consists of non-malignant cells, such as carcinoma-associated fibroblasts, which are specialized mesenchymal cell types distinctive to each tissue environment. Furthermore, the extracellular matrix includes and interacts with structural proteins (such as collagen or elastin), regulatory proteins (such as periostin, fibrilin and fibronectin), innate and adaptive immune cells (7,8), the vasculature (endothelial cells and pericytes) and proteoglycans (9,10). By consecutive genetic alterations, normal parenchymal cells switch to malignant tumor cells, while the change of the stromal host compartment consequently leads to a supportive or hostile environment for the cancer cells, depending on the temporal and spatial sequence, and the tumor type. Mandatory alterations in the microenvironment contributing to cancer invasion consist of degradation of the basement membrane, activation of the stroma and formation of new tumor feeding capillaries (11).

In a previous study, we defined the activated stroma index as an independent prognostic marker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (12). In pancreatic cancer, typically the vast majority of the tumor volume consists of non-malignant stroma cells, which in turn produce excessive extracellular matrix proteins, creating a highly desmoplastic microenvironment (13). The so-called activated stroma index is defined as the ratio of stromal activity measured by α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen deposition; it indicates paracrine secretion of periostin and other tumor stimulating factors, which is associated with a worsened prognosis (12,13). Contrary to pancreatic cancer, where periostin is exclusively produced by the stroma (14), in NSCLC, tumor cells also produce periostin (15). Thus, periostin marks epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is a characteristic of highly tumorigenic cells promoting tumor progression (15,16). The present study investigated the role of periostin and the activated stroma index in NSCLC.

Patients and methods

Patient and tissue samples

The collection of material and data was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Bayerische Ärztekammer (Munich, Germany), the Ludwigs-Maximilian University (Munich, Germany) and the Technical University of Munich (Munich, Germany). This study was conducted on an anonymized data set. Clinical data and the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues of 93 patients was retrospectively collected for analysis. All available tissue from patients who underwent surgery for NSCLC with curative intent between February 2003 and December 2006 at the Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, were identified and analyzed, without further limitations. Patient characteristics are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Median age, years | |

| Males | 69 |

| Females | 62 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 56 (60.2) |

| Female | 37 (39.8) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 66 (71.0) |

| Squamous carcinoma | 22 (23.7) |

| Large cell carcinoma | 3 (3.2) |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 2 (2.2) |

| Tumor status, n (%) | |

| T1 | 3 (3.2) |

| T2 | 34 (36.6) |

| T3 | 55 (59.1) |

| Not specified | 1 (1.1) |

| Nodal status, n (%) | |

| N0 | 60 (64.5) |

| N1 | 20 (21.5) |

| N2 | 12 (12.9) |

| N3 | 1 (1.1) |

| Grade, n (%) | |

| G1 | 3 (3.2) |

| G2 | 34 (36.6) |

| G3 | 55 (59.1) |

| Not specified | 1 (1.1) |

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis of periostin, α-SMA and cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31), and collagen-specific aniline blue assessment was performed in 93 samples according to the manufacturer's instructions, as described previously (13,17,18). Briefly, 3-µm sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were stained with polyclonal rabbit periostin (1:4,000 dilution; catalog no. RD181045050; Biovendor GmbH, Kassel, Germany), monoclonal mouse α-SMA (1:1,500 dilution; catalog no. M0851; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and monoclonal mouse CD31 (1:50 dilution; catalog no. M0823; Dako) antibodies, and with the collagen-specific aniline blue of the Masson trichrome stain, without applying hematoxylin or Biebrich scarlet-acid fuchsin as counterstaining.

Slide evaluation

Slides were scanned with a Nikon coolscan V (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 4,000 dots per inch. The digital images were analyzed for the total surface area vs. stained area using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), as described previously (12). Briefly, histograms of gray-scale converted images were used to quantify the surface area in pixels. The upper and lower input levels were overlapped to create black or white image areas, without an intermediate zone. For best sensitivity of detection, the point of overlap was set to the vertex of the initial exponential phase of the histogram curve. After identifying the best adjustments, values were kept throughout all analyses. The median surface area analyzed was 159 mm2 per section, which corresponds to >1,000 high-power fields (x× magnification). The immunohistochemical analysis and quantification of the activated stroma index were arranged in a manner that was blinded to the clinical data. Median values were used as the cut-off to define sections with high and low levels. The activated stroma index, defined as the ratio of the α-SMA-stained area to the collagen-stained area, was defined in the same manner (12). For visualization, immunohistochemical analyses were repeated for periostin, α-SMA and CD31 in representative blocks.

Statistical analysis

Time-dependent survival probabilities were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method; the log-rank test was used to compare subgroups. Overall survival was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis until mortality or last follow-up. To investigate the effect on survival of multivariable associations among covariates, Cox proportional hazard models were used. Survival times and estimated hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were reported. To avoid over-adjustment in the multivariable survival analysis due to the limited sample size, consecutively (one by one) testing of the putative confounders tumor stage (T), lymph node status (N) and grading (G) was performed. All tests were two-sided, and P-values of <0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. No correction of P-values was applied to adjust for multiple test issues. However, the results of all conducted statistical tests are thoroughly reported, so that an informal adjustment of P-values can be performed while reviewing the data (19). Statistical testing was performed using IBM® SPSS® statics software, version 19 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Study group

The study group consisted of 93 patients with NSCLC. Of those, 66 patients presented with adenocarcinoma, 22 with squamous cell carcinoma, 3 with large cell carcinoma and 2 with adenosquamous cell carcinoma. There were 56 men (60.2%) and 37 women (39.8%). The median age at diagnosis was 69 years in the men and 62 years in the women. Clinical and histopathological patient characteristics are shown in Table I.

Immunohistochemistry

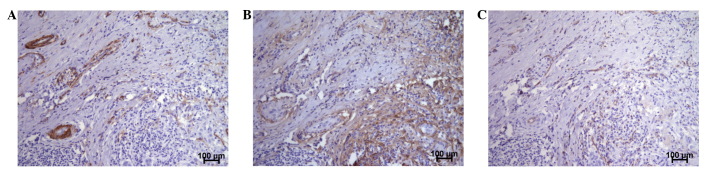

Sections of NSCLC were stained against periostin as a matrix protein and against α-SMA to detect myofibroblasts. High periostin expression was found in areas that co-localized with myofibroblasts (Fig. 1A and B). These myofibroblasts were predominantly found around cancer cells. By contrast, the vessel density analyzed by the endothelial marker CD31 (Fig. 1C) was evenly distributed over the whole specimen.

Figure 1.

Patterns of periostin expression, myofibroblasts and vessel occurrence on consecutive lung cancer sections. Anti-periostin and anti-α-SMA antibodies were used to detect extracellular matrix and myofibroblasts, and anti-CD31 was used to stain vessels/endothelial cells (x× magnification). (A) α-SMA positive myofibroblasts were predominantly found beneath cancer cells. (B) Within the cancerous regions, periostin expression co-localized with areas of myofibroblasts. (C) Endothelial cells were evenly distributed over the whole tissue. CD31, cluster of differentiation 31; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

Univariable survival analysis

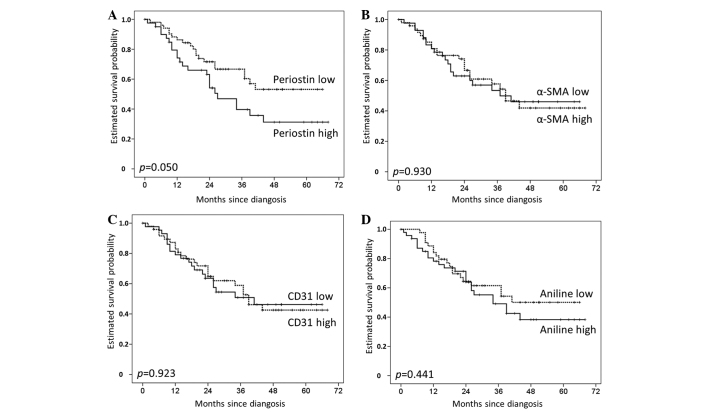

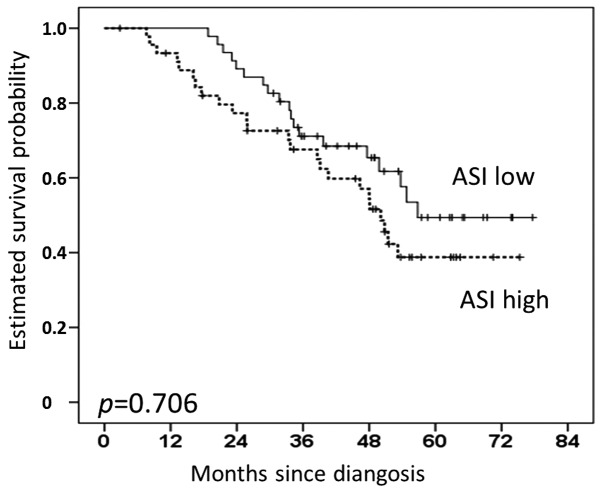

There was a trend towards reduced overall survival for patients with high periostin levels, as defined by the median (HR 1.80; 95% CI, 0.99–3.27; P=0.050). However, this did not reach statistical significance. The 1− and 2-year survival rates for patients with high periostin levels were 74 and 63%, respectively, compared with 85 and 72%, respectively, for those with low periostin expression (Fig. 2). Survival differences were even less pronounced for α-SMA (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.56–1.88; P=0.930), CD31 (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.57–1.88; P=0.923) and aniline (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.69–2.31; P=0.441). No significant survival difference existed for the activated stroma index, defined as the quotient of the α-SMA- and aniline-stained areas (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.62–2.04; P=0.706) (Fig. 3). In the univariable survival analysis of clinical and other histopathological factors, only the resection status (R0 vs. R1, P=0.030) and nodal tumor involvement were statistically significant predictors of a poor prognosis. The hazard ratio was more than doubled for patients with N1 compared with N0 (P=0.026), and more than four times greater for patients with N2/3 compared with N0 (P<0.001) (Table II). The histological tumor subtype (adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma; P=0.211), T stage (P=0.189), grading (P=0.507) and gender (P=0.055) exhibited no significant effect on survival upon univariable analysis [log-rank (Mantel-Cox)].

Figure 2.

Correlation of (A) periostin, (B) α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), (C) cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31) and (D) aniline expression with overall survival.

Figure 3.

Correlation of the activated stroma index (ASI) with overall survival.

Table II.

Univariable cox regression analysis on overall survival.

| Parameter | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Periostin (high) | 1.80 | 0.99–3.27 | 0.050 |

| α-SMA (high) | 1.03 | 0.56–1.88 | 0.930 |

| CD31 (high) | 1.03 | 0.57–1.88 | 0.923 |

| Collagen (high) | 1.26 | 0.69–2.31 | 0.441 |

| ASI (high) | 1.12 | 0.62–2.04 | 0.706 |

| Nodal status | 0.001a | ||

| N1/N0 | 2.27 | 1.10–4.67 | 0.026 |

| N2–3/N0 | 4.05 | 1.96–8.37 | <0.001 |

| Grade | 0.823a | ||

| G2/G3 | 0.82 | 0.44–1.54 | 0.533 |

| Tumor status | 0.222a | ||

| T2/T1 | 1.47 | 0.69–3.16 | 0.321 |

| T3/T1 | 2.06 | 0.73–5.79 | 0.171 |

| T4/T1 | 3.64 | 0.97–13.6 | 0.055 |

ASI, activated stroma index (1);

likelihood ratio test for overall effect.

Multivariable survival analysis

A multivariable analysis was performed in order to investigate the role of periostin as an independent prognostic factor after adjustment for the clinical and histopathological parameters: Tumor type, stage (T), lymph node involvement (N), grading (G), resection status (R) and gender. In concordance with the univariable analysis, periostin was not identified as an independent prognostic factor (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.21–1.24; P=0.137; Table III). Due to the limited number of patients in the study, not all immunohistochemical markers (periostin, α-SMA, CD31, aniline, and the activated stroma index) could be included simultaneously in order to receive reliable results. Thus, another multivariable analysis was performed, with consecutive (one by one) adjustment of the effects of expression profiles for potentially confounding factors T, N and G. However, none of the immunohistochemical markers were found to be independent prognostic factors (Table IV).

Table III.

Multivariable cox regression analysis on overall survival for periostin, adjusted for clinical and histopathological factors.

| 95% confidence interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | P-value | Hazard ratio | Lower | Upper |

| Periostin low (vs. high) | 0.137 | 0.52 | 0.21 | 1.24 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 0.047 | 1.00 | ||

| vs. Squamous | 0.036 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.85 |

| vs. Large cell | 0.033 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.80 |

| vs. Adenosquamous | 0.412 | 4.84 | 0.11 | 208.76 |

| T1 | 0.119 | 1.00 | ||

| vs. T2 | 0.058 | 11.75 | 0.92 | 150.64 |

| vs. T3 | 0.019 | 25.89 | 1.72 | 390.69 |

| vs. T4 | 0.041 | 10.25 | 1.11 | 95.11 |

| N0 | 0.005 | 1.00 | ||

| vs. N1 | 0.695 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 6.16 |

| vs. N2 | 0.394 | 2.82 | 0.26 | 30.74 |

| vs. N3 | 0.124 | 9.66 | 0.54 | 174.09 |

| G1 | 0.773 | 1.00 | ||

| vs. G2 | 0.988 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| vs. G3 | 0.473 | 0.70 | 0.26 | 1.87 |

| R0 (vs. R1) | 0.010 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.59 |

| Male (vs. Female) | 0.599 | 1.30 | 0.49 | 3.43 |

T, tumor status; N, nodal involvement; G, grade.

Table IV.

Consecutive (one by one) multivariable cox regression analysis on overall survival for the immunohistochemical tested markers, with adjustment for the putative relevant histopathological confounding factors.

| Periostin (high vs. low) | α-SMA (high vs. low) | CD31 (high vs. low) | Anilin (high vs. low) | ASI (high vs. low) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment variable (potential confounder) | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Nodal status | 1.52 | 0.83–2.78 | 0.175 | 0.98 | 0.53–1.79 | 0.939 | 0.81 | 0.44–1.49 | 0.492 | 1.08 | 0.58–2.01 | 0.814 | 0.94 | 0.50–1.74 | 0.84 |

| Grade | 1.69 | 0.91–3.13 | 0.097 | 0.93 | 0.50–1.72 | 0.822 | 0.85 | 0.46–1.58 | 0.614 | 1.21 | 0.66–2.23 | 0.544 | 1.09 | 0.60–2.00 | 0.78 |

| Tumor status | 1.69 | 0.91–3.13 | 0.094 | 1.16 | 0.61–2.19 | 0.658 | 1.09 | 0.58–2.05 | 0.795 | 1.46 | 0.76–2.80 | 0.252 | 1.17 | 0.64–2.13 | 0.62 |

ASI, activated stroma index; CD31, cluster of differentiation 31; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

The invasiveness of cancer cells is facilitated by EMT, among other things. The basis of EMT involves multiple changes in expression, distribution and/or function of proteins, such as periostin, vimentin and integrin (20,21). Periostin physiologically regulates bone/tooth formation and maintenance, as well as cardiac development and healing (15). Pathophysiologically, it further plays an important role in tumor development, with upregulation in a variety of cancers, including colon, pancreatic, ovarian, breast, head and neck, thyroid and gastric cancer, and NSCLC (15). Periostin can co-localize with fibronectin and collagen, thereby promoting an extracellular matrix organization, which supports invasion and metastasis. This process is regulated through the binding of periostin on integrin receptors and the downstream activation of focal adhesion kinase and Akt/phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signaling (15). As we have shown previously, a highly active stroma is characterized by high levels of periostin and α-SMA, as well as reduced levels of dormant collagen deposits. This corresponds to a high grade of EMT and is an independent poor prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer (12). However, a few studies of bladder cancer and osteosarcoma have described periostin as a tumor-inhibiting factor in these entities (15,22,23). One main difference between pancreatic cancer and NSCLC is that in lung cancer, periostin is not only expressed from activated stellate cells, likewise, cancer cells are able to produce and secrete this extracellular matrix molecule (14–16). Morra and Moch found that upregulation of the extracellular matrix protein periostin is correlated with a worse prognosis in numerous tumor entities, and that although dependent on the tumor entity, periostin can be produced by both the cancer cells and the peritumoral component of the stroma (15). In the case of NSCLC, detectable periostin expression was described to be mostly produced by the tumor cells themselves, rather than by the stroma (15). By contrast, the present study detected high periostin expression in areas co-localized with myofibroblasts, which in turn were found around the cancer cells (Fig. 1B). Thus, the exact mechanism of periostin production in NSCLC remains unclear and should be a matter for further investigation.

The activity of myofibroblasts (e.g., stellate cells in the pancreas) is indicated by α-SMA expression and implicates a worsened prognosis, as found in the pancreas (12). The present study provides evidence that patients with elevated α-SMA expression in NSCLC have a reduced prognosis as well; although these data were not statistically significant. The activity of myofibroblasts is associated with collagen deposition. For this, the activated stroma index, a prognostic factor that is defined as the ratio of α-SMA-stained regions against collagen-stained areas, was calculated (12). In pancreatic cancer with its large collagen deposits, a worse prognosis was found in patients with high intratumoral stromal activity, defined by high α-SMA activity together with low collagen deposition (12). However, NSCLC appears to have a clearly different stromal composition (6,24), and the activated stroma index was not confirmed as a significant prognostic factor in the present study.

Neoangiogenesis plays a crucial role in tumor growth and metastasis. Several studies have demonstrated that neoangiogenesis is a significant prognostic factor for overall survival in lung cancer, and currently there are a number of inhibitors of angiogenesis in clinical use for the treatment of cancer (25–28). The intratumoral microvessel density is a predictor of tumor growth, metastasis and patient survival (29). However, recent data suggested no significant differences in the microvessel density of bronchial normal mucosa, metaplasia, dysplasia and carcinoma in situ (30). Thus, it is not yet clear in which step of bronchial carcinogenesis angiogenesis actually plays the most crucial role (30). Double immunostaining for CD31 and α-SMA allows the estimation of juvenile blood vessels in neoplasms (30). In the present study the impact of microvessel density was analyzed; however, there was no significant survival difference for patients with low versus high microvessel density.

The present study described the tumor microenvironment and EMT in NSCLC. Considering that pancreatic cancer exhibits mutual activation of tumor cells and the surrounding stroma (12), these tumor-stroma interactions were expected for other entities as well. However, despite the limited sample size and inclusion of different tumor entities (NSCLC) (16), no such significant stroma activation was observed in NSCLC. NSCLC has distinct histopathological characteristics. Tumor-stroma interactions and the tumor microenvironment play an important role; however, the most relevant candidate markers and paracrine or autocrine crosstalk pathways appear to be different from those known for pancreatic cancer (6,24).

In conclusion, stroma activation was not confirmed as an independent prognostic factor for patients with NSCLC in this retrospective study. Together with previous results, this highlights the heterogeneity of different cancer entities and the requirement for future highly individualized therapeutic concepts.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a donation from the Marianne-Lutter Nachlass and by Koc University (Istanbul, Turkey).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1367–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstraw P, Ball D, Jett JR, Le Chevalier T, Lim E, Nicholson AG, Shepherd FA. Non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:1727–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heukamp LC, Büttner R. Molecular diagnostics in lung carcinoma for therapy stratification. Pathologe. 2010;31:22–28. doi: 10.1007/s00292-009-1241-1. (In German) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:581–592. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Nikhely N, Larzabal L, Seeger W, Calvo A, Savai R. Tumor-stromal interactions in lung cancer: Novel candidate targets for therapeutic intervention. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1107–1122. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.693478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bremnes RM, Dønnem T, Al-Saad S, Al-Shibli K, Andersen S, Sirera R, Camps C, Marinez I, Busund LT. The role of tumor stroma in cancer progression and prognosis: Emphasis on carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:209–217. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f8a1bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunér S, Lindman J Lopatko, Ansari D, Gundewar C, Andersson R. Pancreatic cancer: The role of pancreatic stellate cells in tumor progression. Pancreatology. 2010;10:673–681. doi: 10.1159/000320711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalluri R. Basement membranes: Structure, assembly and role in tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:422–433. doi: 10.1038/nrc1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erkan M, Michalski CW, Rieder S, Reiser-Erkan C, Abiatari I, Kolb A, Giese NA, Esposito I, Friess H, Kleeff J. The activated stroma index is a novel and independent prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erkan M, Kleeff J, Gorbachevski A, Reiser C, Mitkus T, Esposito I, Giese T, Büchler MW, Giese NA, Friess H. Periostin creates a tumor-supportive microenvironment in the pancreas by sustaining fibrogenic stellate cell activity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1447–1464. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanno A, Satoh K, Masamune A, Hirota M, Kimura K, Umino J, Hamada S, Satoh A, Egawa S, Motoi F, et al. Periostin, secreted from stromal cells, has biphasic effect on cell migration and correlates with the epithelial to mesenchymal transition of human pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2707–2718. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morra L, Moch H. Periostin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: A review and an update. Virchows Arch. 2011;459:465–475. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong LZ, Wei XW, Chen JF, Shi Y. Overexpression of periostin predicts poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1595–1603. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erkan M, Kleeff J, Esposito I, Giese T, Ketterer K, Büchler MW, Giese NA, Friess H. Loss of BNIP3 expression is a late event in pancreatic cancer contributing to chemoresistance and worsened prognosis. Oncogene. 2005;24:4421–4432. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalski CW, Shi X, Reiser C, Fachinger P, Zimmermann A, Büchler MW, Di Sebastiano P, Friess H. Neurokinin-2 receptor levels correlate with intensity, frequency, and duration of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:786–793. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318070d56e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saville DJ. Multiple comparison procedures: The practical solution. Am Stat. 1990;44:174–180. doi: 10.2307/2684163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soltermann A, Tischler V, Arbogast S, Braun J, Probst-Hensch N, Weder W, Moch H, Kristiansen G. Prognostic significance of epithelial-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-epithelial transition protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7430–7437. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan W, Shao R. Transduction of a mesenchyme-specific gene periostin into 293T cells induces cell invasive activity through epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19700–19708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim CJ, Yoshioka N, Tambe Y, Kushima R, Okada Y, Inoue H. Periostin is down-regulated in high grade human bladder cancers and suppresses in vitro cell invasiveness and in vivo metastasis of cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:51–58. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshioka N, Fuji S, Shimakage M, Kodama K, Hakura A, Yutsudo M, Inoue H, Nojima H. Suppression of anchorage-independent growth of human cancer cell lines by the TRIF52/periostin/OSF-2 gene. Exp Cell Res. 2002;279:91–99. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi H, Sheng J, Gao D, Li F, Durrans A, Ryu S, Lee SB, Narula N, Rafii S, Elemento O, et al. Transcriptome analysis of individual stromal cell populations identifies stroma-tumor crosstalk in mouse lung cancer model. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1187–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yano T, Tanikawa S, Fujie T, Masutani M, Horie T. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression and neovascularisation in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:601–609. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giatromanolaki A, Koukourakis MI, Theodossiou D, Barbatis K, O'Byrne K, Harris AL, Gatter KC. Comparative evaluation of angiogenesis assessment with anti-factor-VIII and anti-CD31 immunostaining in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2485–2492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han H, Silverman JF, Santucci TS, Macherey RS, d'Amato TA, Tung MY, Weyant RJ, Landreneau RJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in stage I non-small cell lung cancer correlates with neoangiogenesis and a poor prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:72–79. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0072-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, O'Byrne KJ, Whitehouse RM, Talbot DC, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Potential role of bcl-2 as a suppressor of tumour angiogenesis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:565–570. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971219)74:6<565::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma S, Sharma MC, Sarkar C. Morphology of angiogenesis in human cancer: A conceptual overview, histoprognostic perspective and significance of neoangiogenesis. Histopathology. 2005;46:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raica M, Cimpean AM, Ribatti D. Angiogenesis in pre-malignant conditions. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1924–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]