Abstract

Objectives

To determine prevalence of post-MI LV thrombus in the current era, and develop an effective algorithm – predicated on echocardiography (echo) - to discern patients warranting further testing for thrombus via delayed-enhancement (DE-) CMR.

Background

LV thrombus impacts post-MI management. DE-CMR provides thrombus tissue characterization and is well validated but an impractical screening modality for all post-MI patients.

Methods

Same day echo and CMR were performed via a tailored protocol, which entailed uniform echo contrast (irrespective of image quality) and dedicated DE-CMR for thrombus tissue characterization.

Results

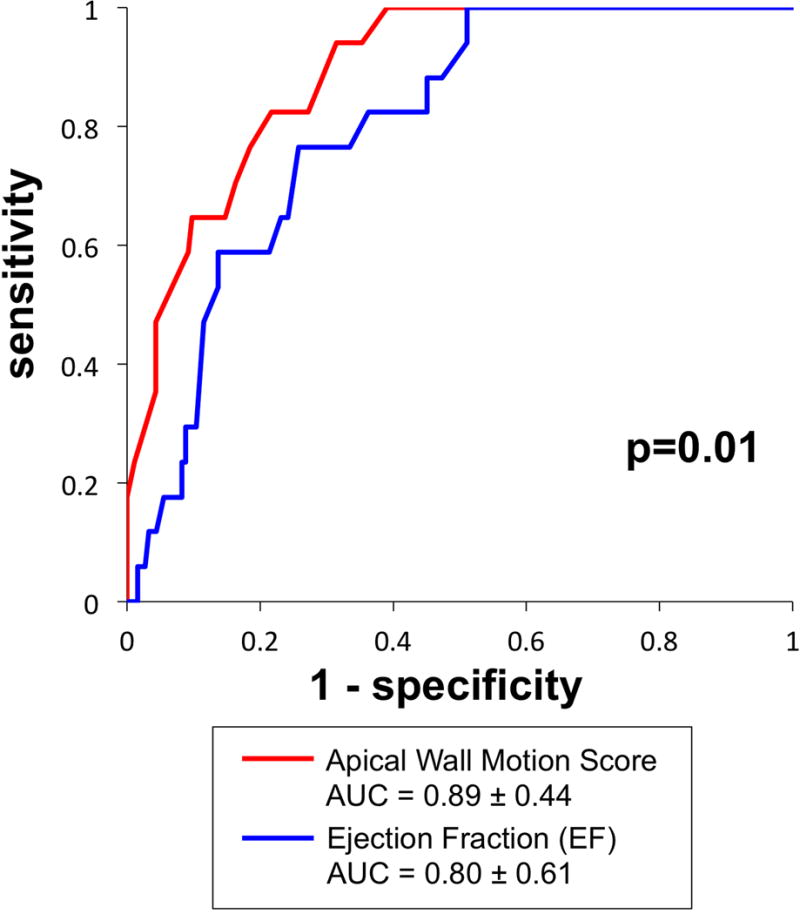

201 patients were studied; 8% had thrombus via DE-CMR. All thrombi were apically located – 94% occurred with LAD MI. Whereas patients with thrombus had more prolonged chest pain and larger MI (p≤0.01), only 18% had aneurysm on echo (cine-CMR 24%). Non-contrast (35%) and contrast echo (64%) yielded limited sensitivity for thrombus on DE-CMR. Thrombus was associated with stepwise increments in basal → apical contractile dysfunction on echo and quantitative cine-CMR; echo-measured apical wall motion score was higher among patients with thrombus (p<0.001) and paralleled cine-CMR decrements in apical EF and peak ejection rates (both p<0.005). Thrombus-associated decrements in apical contractile dysfunction were significant even among patients with LAD infarction (p<0.05). Echo-based apical wall motion score improved overall performance (AUC 0.89±0.44) for thrombus compared to EF (AUC 0.80±0.61; p=0.01): Apical wall motion partitions would have enabled all patients with LV thrombus to be appropriately referred for DE-CMR (100% sensitivity and negative predictive value), while avoiding further testing in over half (56–63%) of patients.

Conclusions

LV thrombus remains common especially after LAD MI, and can occur even in absence of aneurysm. Whereas DE-CMR yields improved overall thrombus detection, apical wall motion on non-contrast echo can be used as an effective stratification tool to identify patients in whom DE-CMR thrombus assessment is most warranted.

Keywords: left ventricular thrombus, cardiovascular magnetic resonance, echocardiography

Introduction

LV thrombus is an important complication of acute MI that impacts embolic event risk and anticoagulant therapy. Echo is widely used to assess post-MI LV structure and function, but can be limited for LV thrombus in the context of poor image quality or advanced LV remodeling (1,2). Delayed enhancement (DE-) CMR identifies thrombus based on avascular tissue properties, an approach shown to markedly improve thrombus detection (1–5). However, widespread use of DE-CMR as an initial screening modality for thrombus would entail significant costs and be clinically prohibited for a substantial number of post-MI patients.

Improved understanding of post-MI thrombus in the current era is critical for optimization of diagnostic testing strategies. Advances in MI management – including prompt and effective coronary reperfusion – have yielded improvements in LV function and remodeling. Widespread use of antiplatelet agents may potentiate benefits of reperfusion, thereby lessening likelihood of LV thrombus. However, risk for thrombus still persists, especially for patients with infarctions in high-risk regions such as the LV apex. Uncertainty regarding current prevalence and pathophysiology of thrombus limits the ability to develop practical and effective imaging strategies for the millions of post-MI patients at risk for LV thrombus and its complications.

This study employed a tailored multimodality imaging protocol – including state-of-the-art echo and CMR – to examine post-MI LV thrombus. Aims were as follows: (1) determine prevalence and predictors of thrombus; (2) assess diagnostic performance of optimized current testing strategies (non-contrast and contrast echo) to a reference standard of DE-CMR tissue characterization; and (3) develop an effective testing algorithm – predicated on routine non-contrast echo findings - to identify post-MI patients warranting further testing for LV thrombus via DE-CMR.

Methods

Study Population

The population comprised acute MI patients enrolled in a prospective study (clinical trial # NCT00539045) focused on LV thrombus. Patients were eligible for inclusion if admitted with acute ST elevation MI (≥1.0mm in at least 2 contiguous ECG leads). Patients with contra-indications to CMR (e.g. GFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2, ferromagnetic implants, NYHA class IV) or on warfarin (at time of CMR) were excluded; no patients were excluded based on MI treatment. Patients were approached for study participation using a random selection algorithm targeted for maximum recruitment of 1 patient per week: Participants were similar to non-participants with respect to infarct-related artery and MI treatment strategy (both p=NS). Comprehensive clinical data were collected at time of MI, including cardiac risk factors, coronary artery disease history, and medications. Coronary angiograms were reviewed for infarct culprit vessel.

This study was conducted at Weill Cornell Medical College with approval of the institutional review board; participants provided written informed consent for study participation.

Imaging Protocol

Imaging was performed at a target of 30 days (minimum 7) post-MI. In accordance with the research protocol, CMR and echo were performed within 24 hours by dedicated technologists - testing included (1) non-contrast echo, (2) contrast echo, (3) cine-CMR, and (4) DE-CMR. To identify factors predicting incremental utility of tailored imaging for thrombus, contrast echo was performed in all patients (without clinical contraindication) irrespective of image quality or findings of non-contrast echo. Similarly, DE-CMR included dedicated imaging using a previously validated “long inversion time” (long TI) pulse sequence tailored to null LV thrombus (1,2,6).

CMR

CMR was performed using 1.5 Tesla scanners (General Electric [Waukesha, WI]). Cine-CMR utilized a steady-state free precession pulse sequence. Gadolinium was subsequently administered (0.2 mmol/kg) and DE-CMR performed 10–30 minutes thereafter using an inversion recovery pulse sequence. Cine-CMR and DE-CMR images were obtained in matching short- and long-axis planes. Contiguous short-axis images were acquired from the level of the mitral annulus through the apex. Long-axis images were acquired in 2-, 3- and 4-chamber orientations. DE-CMR included standard (TI=250–350msec) imaging for MI, and “long TI” imaging (TI=600msec) for dedicated identification of LV thrombus; both were acquired using segmented imaging. Standard and long TI DE-CMR were acquired in matching LV long axis orientations at equivalent spatial resolution (mean in-plane 1.9 × 1.4mm).

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echoes were performed by experienced sonographers using commercial equipment (General Electric Vivid-7, Siemens SC2000 [Malvern, PA]). Images were acquired in long- and short-axis orientations concordant with American Society of Echocardiography guidelines (7). Following non-contrast imaging, an echo contrast agent (DEFINITY; Lantheus Medical Imaging) was infused via the diluted bolus technique in accordance with manufacturer guidelines. Sonographers then repeated imaging so as to acquire non-contrast and contrast echo images in matching orientations.

LV Thrombus Identification

DE-CMR

Thrombus was identified as an LV mass with avascular tissue properties on post-contrast inversion-recovery imaging. Concordant with prior validation studies (1,2,8), selective nulling of avascular tissue (i.e., thrombus) was performed using an inversion time of 600msec, such that thrombus appeared black and was easily identifiable in relation to surrounding high signal intensity regions such as intracavitary blood and LV myocardium (Figure 1). Thrombus was deemed present on DE-CMR if visualized on any long TI image. Thrombi were also scored for location (assigned using an AHA/ACC 17 segment model).

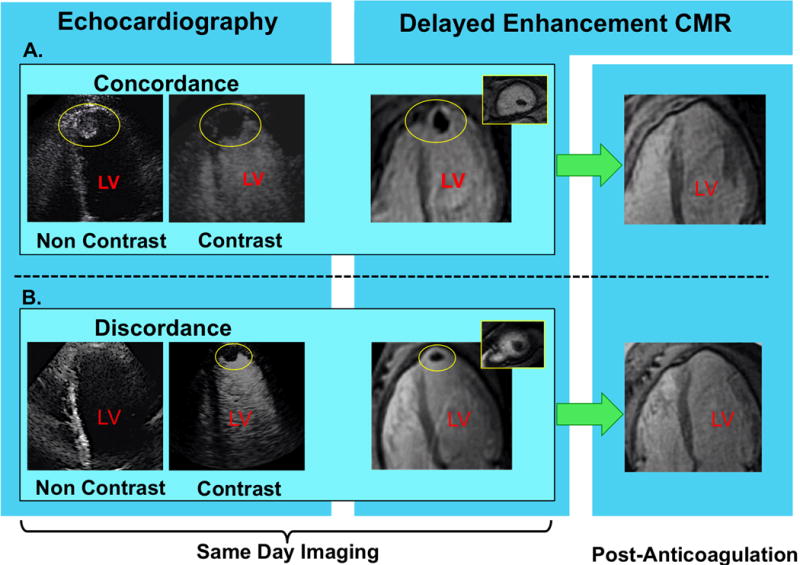

Figure 1. LV Thrombus Detection by Non-Contrast and Contrast Echo.

Representative examples of (1A) LV thrombus concordantly detected by non-contrast (left) and contrast (right) echo, and (1B) improved detection of LV thrombus via contrast echo. Images displayed in 4-chamber orientation (thrombus denoted by yellow circle).

In both examples, DE-CMR confirmed contrast echo results, as evidenced by thrombus-associated avascularity within the LV apex (images shown in 4-chamber [corresponding to echo], and short axis orientation [inset]). As shown on far right (green arrows), both cases also demonstrated resolution of DE-CMR-evidenced thrombus following treatment with warfarin-based anticoagulation.

Echocardiography

Thrombus was diagnosed on echo using established criteria (1,8,9), for which it was defined as a protuberant or independently mobile mass in the LV cavity distinguishable from papillary muscles, trabeculae, chordal structures, technical artifact, or tangential views of the LV wall (Figure 1).

Echoes were also scored for diagnostic quality using a previously established 9-point scale comprised of separate scores for endocardial definition (1=poor, 2=fair, 3=excellent), cavity artifacts (1=present and obscuring full LV assessment, 2=present but interpretable, 3=absent), number of apical views (1=single orientation, 2=at least two orientations), and number of LV segments imaged (1=all segments) (1).

Echo and CMR were each interpreted by experienced (ACC/AHA level III) physicians (echo - RBD │CMR - JWW) for whom high inter- and intra-reader reproducibility concerning diagnosis of LV thrombus has been reported (1). Readers were blinded to clinical history and results of other imaging modalities: Cine- and DE-CMR, as well as non-contrast and contrast echo, were each read independently.

Myocardial Infarction

MI was quantified on conventional (TI 250–350msec) DE-CMR. Infarct transmurality was graded on a 5-point scale for each affected LV segment (0=no hyperenhancement; 1=1–25%; 2=26–50%; 3=51–75%; 4=76–100%). Global infarct size (% LV myocardium) was calculated by summing segmental scores and dividing by the total number of regions (10).

Global and Regional LV Deformation

LV deformation parameters were measured on echo and CMR to identify contractile indices associated with LV thrombus and discern those patients in whom DE-CMR tissue characterization is most warranted.

Global LV geometry and function were quantified on cine-CMR based on planimetry of end-diastolic and end-systolic chamber volumes, which yielded LV ejection fraction (EF) and stroke volume. Corresponding echo parameters were quantified based on linear chamber dimensions, for which measurements were performed in accordance with ASE guidelines as previously applied by our group in population-based research (11,12). Cine-CMR and echo were also scored for LV aneurysm, defined as a dyskinetic bulge interrupting the LV contour in diastole and systole (1,13).

Regional LV deformation was measured using established echo and recently developed cine-CMR methods. For echo, regional wall motion was scored using an AHA/ACC 17-segment model, for which segmental contraction was graded as follows: 0=normal; 1=mild hypokinesis; 2=moderate hypokinesis; 3=severe hypokinesis; 4=akinesis; 5=dyskinesis. Apical LV wall motion scores were calculated on non-contrast and contrast echo by summing segmental scores within the apical LV and true apex (total 5 segments). For cine-CMR, regional deformation was quantified using a validated automated algorithm for volumetric segmentation (14–16), which measured temporal and geometric deformation patterns at equidistant locations in the basal, mid, and apical LV.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons between groups with or without thrombus were made using Student’s t test (expressed as mean ± standard deviation) for normally distributed continuous variables. Non-normally distributed variables (median, interquartile range) were compared via the Mann Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square or, when fewer than 5 expected outcomes per cell, Fisher’s exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to test associations between echo variables and thrombus. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc. [Chicago, IL]). ROC analysis was used to evaluate diagnostic performance of echo parameters for detection of thrombus; comparison between ROC curves was performed using the DeLong test with pROC, a statistical package for R (17,18). Two-sided p<0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Population Characteristics

The population comprised 201 patients who underwent a multimodality imaging protocol following acute ST segment elevation MI. Imaging was performed 28±6 days post MI; echo and CMR were obtained within 24 hours. No embolic events or acute coronary syndromes occurred during the interval between MI and imaging.

LV thrombus was present on DE-CMR in 8% (n=17) of the population. Nearly all (94%) thrombi occurred in the context of LAD infarct-related artery. The sole patient with thrombus in whom LCx was the angiography-assigned culprit vessel had concomitant LAD obstruction and findings consistent with LAD injury, as evidenced by apical contractile dysfunction on echo and corresponding Q waves on ECG.

As shown in Table 1, patients with LV thrombus did not differ from those without thrombus with respect to age, gender, or CAD risk factors (all p=NS). Difference in thrombus prevalence between patients treated with primary PCI vs. thrombolytics did not achieve statistical significance (6% vs. 13%, p=0.21). Whereas infarct size and chest pain to PCI duration were greater (both p≤0.01) among patients with thrombus, 41% of affected patients underwent revascularization within a narrow (8-hour) time period. Consistent with this, while LVEF was lower (p<0.001), echo demonstrated that only 12% of patients with thrombus had advanced systolic dysfunction (EF≤30%) and only 18% had LV aneurysm. Results were similar via cine-CMR, which demonstrated advanced LV dysfunction in 12%, and LV aneurysm in only 24% of patients with thrombus.

Table 1.

Clinical and Imaging Characteristics

| Overall (n=201) |

LV Thrombus + (n=17) |

LV Thrombus − (n=184) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL | ||||

| Age (year) | 56±12 | 57±12 | 56±13 | 0.79 |

| Male gender | 84% (169) | 94% (16) | 83% (153) | 0.32 |

| Body Surface Area | 2.0±0.2 | 1.9±0.2 | 2.0±0.2 | 0.50 |

| Coronary Artery Disease Risk | ||||

| Factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 44% (88) | 35% (6) | 45% (82) | 0.46 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 50% (100) | 59% (10) | 49% (90) | 0.43 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 23% (47) | 24% (4) | 23% (43) | 1.00 |

| Tobacco Use | 32% (65) | 35% (6) | 32% (59) | 0.79 |

| Family History | 28% (57) | 29% (5) | 28% (52) | 1.00 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 5% (11) | 12% (2) | 5% (9) | 0.24 |

| Prior Coronary Revascularization | ||||

| Percutaneous Intervention | 8% (17) | 18% (3) | 8% (14) | 0.16 |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting | 1% (1) | – | 1% (1) | 1.00 |

| Cardiovascular Medications | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 96% (192) | 100% (17) | 95% (175) | 1.00 |

| ACE-Inhibitor/Angiotensin Receptor | ||||

| 59% (118) | 71% (12) | 58% (106) | 0.30 | |

| Blocker | ||||

| Loop diuretic | 6% (12) | 18% (3) | 5% (9) | 0.07 |

| HMG CoA-Reductase Inhibitor | 97% (195) | 94% (16) | 97% (179) | 0.42 |

| Antithrombotic Medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 99% (199) | 94% (16) | 99% (183) | 0.16 |

| Thienopyridine | 92% (184) | 82% (14) | 92% (170) | 0.16 |

| LV INFARCTION | ||||

| Infarct-Related Artery | ||||

| Left anterior descending | 54% (108) | 94% (16) | 50% (92) | <0.001 |

| Left circumflex | 10% (20) | 6% (1) | 10% (19) | 1.00 |

| Right coronary | 36% (73) | – | 40% (73) | 0.001 |

| Therapeutic Management | ||||

| Primary Thrombolytics* | 22% (45) | 35% (6) | 21% (39) | 0.22 |

| Primary PCI* | 77% (154) | 59% (10) | 78% (144) | 0.08 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 17% (33) | 24% (4) | 16% (29) | 0.49 |

| Peri-procedural pressors | 10% (19) | 6% (1) | 10% (18) | 1.00 |

| Chest Pain to revascularization interval (hours)† | 6 (3, 23) | 18 (6, 24) | 6 (3, 20) | 0.01 |

| Non Infarct-Related Artery PCI | ||||

| Left anterior descending | 9% (18) | 6% (1) | 9% (17) | 1.00 |

| Left circumflex or right coronary | 7% (14) | 6% (1) | 7% (13) | 1.00 |

| Surgical Revascularization (CABG) | 2% (4) | – | 2% (4) | 1.00 |

| INFARCT SIZE | ||||

| Creatine phosphokinase† | 1514 (606, 2797) | 2758 (1506, 6398) | 1456 (591, 2646) | 0.01 |

| % LV Infarction (DE-CMR)† | 15 (6, 23) | 29 (24, 34) | 14 (5, 21) | <0.001 |

| LV MORPHOLOGY AND FUNCTION | ||||

| Echocardiography | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%)† | 51 (44, 57) | 39 (36, 47) | 52 (45, 58) | <0.001 |

| LVEF ≤ 30% | 4% (8) | 12% (2) | 3% (6) | 0.14 |

| End-diastolic diameter (cm)† | 5.7 (5.2, 6.0) | 5.8 (5.6, 6.2) | 5.6 (5.2, 5.9) | 0.07 |

| End-systolic diameter (cm)† | 4.1 (3.8, 4.6) | 4.8 (4.5, 5.0) | 4.1 (3.8, 4.5) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial Mass (gm)† | 176 (151, 203) | 197 (159, 217) | 176 (150, 201) | 0.14 |

| LV Aneurysm | 3% (6) | 18% (3) | 2% (3) | 0.009 |

| Cardiac Magnetic Resonance | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%)† | 54 (44, 64) | 41 (34, 47) | 56 (47, 64) | <0.001 |

| LVEF ≤ 30% | 2% (4) | 12% (2) | 1% (2) | 0.04 |

| Stroke volume (ml)† | 78 (65, 92) | 70 (58, 76) | 79 (66, 92) | 0.008 |

| End-diastolic volume (ml)† | 147 (124, 171) | 169 (148, 195) | 146 (122, 168) | 0.008 |

| End-systolic volume (ml)† | 64 (49, 90) | 97 (86, 115) | 63 (46, 82) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial mass (gm)† | 131 (111, 152) | 140 (124, 154) | 131 (109, 151) | 0.23 |

| LV Aneurysm | 3% (6) | 24% (4) | 1% (2) | <0.001 |

Bold = p value < 0.05

acute revascularization deferred in 1% (n=2) due to delayed post-MI presentation

data reported as median (interquartile range)

Regional LV Deformation

In all cases, thrombus was located within or adjacent to the LV apex. Consistent with this, LV functional parameters measured in levels from basal to mid to apical LV demonstrated stepwise increases in magnitude of contractile dysfunction between patients with, compared to those without, thrombus. Table 2 details results of cine-CMR analysis using regional volumetric quantification in three equidistant (short-axis) planes in the basal, mid, and apical LV. In the basal LV, volumetric (ejection fraction, peak ejection rate) and temporal (time to peak ejection rate) contractile indices were similar between patients with and without thrombus (all p=NS). Parallel analysis of the mid LV demonstrated moderately lower ejection fraction and stroke volume among patients with thrombus (both p<0.05). In the apical LV, differences were greater with respect to all volumetric and temporal contractile indices, which differed significantly between patients with and without thrombus (p<0.005). Cine-CMR yielded similar results when analysis was restricted to patients with LAD infarction, among whom regional contractility was progressively impaired from the basal to apical LV.

Table 2.

Cine-CMR Quantified Regional LV Volumetric and Temporal Indices*

| Overall Population | LAD Infarction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombus + (n=17) |

Thrombus − (n=184) |

P | Thrombus + (n=16) |

Thrombus − (n=92) |

P | |

|

| ||||||

| Basal Plane | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Ejection Fraction | 52.8 (46.3, 54.7) | 52.7 (45.5, 58.8) | 0.48 | 53.4 (46.3, 54.9) | 55.0 (48.8, 60.5) | 0.06 |

| Stroke Volume | 7.0 (6.1, 7.6) | 6.2 (5.3, 7.2) | 0.08 | 7.0 (6.1, 7.7) | 6.8 (5.8, 7.7) | 0.85 |

| Peak Ejection Rate | 29.3 (24.7, 36.1) | 28.0 (20.6, 33.2) | 0.35 | 28.7 (24.6, 36.0) | 28.8 (23.6, 35.7) | 1.00 |

| Time To Peak Ejection | 201.7 (148.0, 244.3) | 176.1 (138.0, 236.3) | 0.50 | 205.0 (145.5, 245.7) | 183.1 (138.0, 241.0) | 0.60 |

|

| ||||||

| Mid Ventricular Plane | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Ejection Fraction | 41.6 (35.9, 54.2) | 60.1 (48.9, 68.5) | <0.001 | 41.6 (35.2, 51.0) | 57.2 (45.4, 67.5) | 0.002 |

| Stroke Volume | 5.2 (4.0, 6.1) | 5.7 (4.9, 6.5) | 0.03 | 5.0 (4.0, 6.1) | 5.6 (4.7, 6.4) | 0.07 |

| Peak Ejection Rate | 23.0 (20.5, 28.3) | 26.8 (22.1, 30.9) | 0.06 | 22.7 (20.4, 28.1) | 26.1 (20.7, 30.2) | 0.16 |

| Time To Peak Ejection | 173.1 (114.8, 226.2) | 176.1 (146.1, 207.1) | 0.78 | 175.9 (116.5, 232.2) | 183.8 (149.6, 218.5) | 0.55 |

|

| ||||||

| Apical Plane | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Ejection Fraction | 38.3 (24.2, 46.1) | 67.2 (48.9, 78.2) | <0.001 | 34.1 (24.0, 44.4) | 52.0 (33.9, 66.8) | 0.002 |

| Stroke Volume | 2.5 (1.7, 3.4) | 3.5 (2.5, 4.5) | 0.001 | 2.4 (1.7, 3.3) | 2.9 (2.1, 3.8) | 0.08 |

| Peak Ejection Rate | 10.0 (4.1, 15.7) | 15.8 (10.1, 22.4) | 0.002 | 8.6 (4.0, 14.3) | 12.9 (7.8, 19.3) | 0.02 |

| Time To Peak Ejection | 306.1 (193.2, 377.6) | 184.2 (140.8, 246.7) | 0.003 | 311.9 (211.6, 378.9) | 218.1 (160.1, 363.7) | 0.08 |

data reported as median (interquartile range)

Echo analysis – performed via standard visual assessment – paralleled those of quantitative cine-CMR. As shown in Table 3, regional wall motion scores in the basal LV were similar between patients with and without LV thrombus (p=NS). In the mid LV there was a 3-fold difference in median wall motion score (9.0 [IQR 4.0, 12.0] vs. 3.0 [0, 7.0]), and in the apical LV a 6-fold difference (16.0 [10.5, 18.5] vs. 2.5 [0, 8.8]) between patients with and without thrombus. Echo results were similar when analyzed based on contrast-enhanced wall motion scores (Table 3; bottom) and - like cine-CMR – when restricted to patients with LAD infarction.

Table 3.

Echocardiography Quantified Regional LV Contractile Function*

| Overall Population (n=201) | LAD Infarction (n=108) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombus + | Thrombus − | P | Thrombus + | Thrombus − | P | ||

|

| |||||||

| Non-Contrast Echo | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Basal Plane | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wall Motion Score | 4.0 (0, 5.5) | 1 (0, 4.0) | 0.18 | 4.0 (0, 5.8) | 0 (0, 2.0) | 0.02 | |

| Mild/Moderate | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | 0.28 | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | 0.17 | |

| Hypokinesis† | |||||||

| ≥ Severe Hypokinesis† | 0 (0, 1.0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.12 | 0 (0, 1.0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.003 | |

|

| |||||||

| Mid Ventricular Plane | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wall Motion Score | 9.0 (4.0, 12.0) | 3.0 (0, 7.0) | <0.001 | 9.5 (4.8, 12.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 8.8) | 0.007 | |

| Mild/Moderate | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.42 | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.91 | |

| Hypokinesis† | |||||||

| ≥ Severe Hypokinesis† | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | <0.001 | 2.5 (1.0, 3.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Apical Plane | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wall Motion Score | 16.0 (10.5, 18.5) | 2.5 (0, 8.8) | <0.001 | 16.5 (10.3, 18.8) | 7.0 (2.0, 12.8) | <0.001 | |

| Mild/Moderate | 1.0 (0, 1.5) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.81 | 1.0 (0, 1.8) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.33 | |

| Hypokinesis† | |||||||

| ≥ Severe Hypokinesis† | 4.0 (2.0, 5.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | <0.001 | 4.0 (2.0, 5.0) | 1.0 (0, 3.0) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Contrast Echo‡ | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Basal Plane | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wall Motion Score | 3.5 (0, 5.0) | 1.0 (0, 4.0) | 0.35 | 3.5 (0, 5.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | 0.045 | |

| Mild/Moderate | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | 0.28 | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0 (0, 1.0) | 0.09 | |

| Hypokinesis† | |||||||

| ≥ Severe Hypokinesis† | 0 (0, 1.0) | 0 (0, 0.0) | 0.37 | 0 (0, 1.0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.02 | |

|

| |||||||

| Mid Ventricular Plane | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wall Motion Score | 9.5 (5.5, 12.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 0.001 | 9.5 (5.5, 12.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 8.0) | 0.001 | |

| Mild/Moderate | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.32 | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.67 | |

| Hypokinesis† | |||||||

| ≥ Severe Hypokinesis† | 2.5 (1.0, 3.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | <0.001 | 2.5 (1.0, 3.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Apical Plane | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Wall Motion Score | 16.5 (11.3, 19.0) | 3.0 (0, 8.0) | <0.001 | 16.5 (11.3, 19.0) | 6.0 (2.0, 12.0) | <0.001 | |

| Mild/Moderate | 1.0 (0, 1.0) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.66 | 1.0 (0, 1.0) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 0.28 | |

| Hypokinesis† | |||||||

| ≥ Severe Hypokinesis† | 4.0 (2.8, 5.0) | 0 (0, 2.0) | <0.001 | 4.0 (2.8, 5.0) | 1.0 (0, 3.0) | <0.001 | |

data reported as median (interquartile range)

# segments (for each respective LV geometric location)

contrast not administered to 5% (n=11) due to clinical contraindications or patient refusal

Both echo-evidenced apical wall motion score (OR = 1.29 per point [CI 1.16–1.44], p<0.001) and LV aneurysm (OR = 12.93 [CI 2.39–70.08], p=0.003) were associated with DE-CMR evidenced LV thrombus in univariate logistic regression. However, multivariate regression demonstrated apical wall motion score (OR = 1.28 per point [CI 1.15–1.43], p<0.001) to be associated with thrombus after controlling for aneurysm (OR = 1.96 [CI 0.31–12.44], p=0.48) (model χ2 = 35.54, p<0.001).

Diagnostic Performance

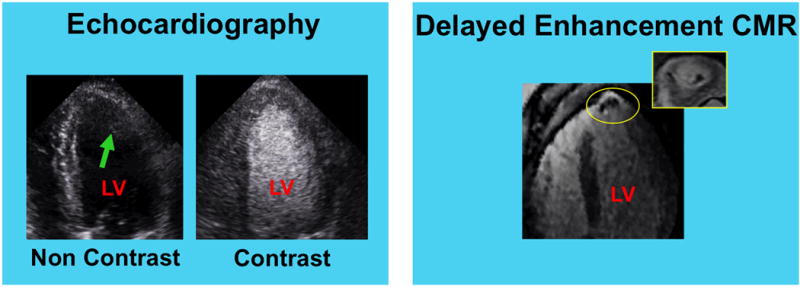

Table 4 reports diagnostic performance of non-contrast and contrast echo, as well as cine-CMR, compared to the reference of DE-CMR. Importantly, dedicated non-contrast echo did provide high specificity (98%), which was near equivalent to that of contrast echo (99%). However, despite the fact that all exams were tailored for LV thrombus evaluation, non-contrast echo yielded limited sensitivity (35%), which remained sub-optimal with use of echo contrast (64%). Figures 1 and 2 provide representative examples of echo performance, including incremental utility of contrast echo (Figure 1B) as well as DE-CMR evidenced thrombus missed by both echo techniques (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Diagnostic Performance for LV Thrombus

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Non-Contrast Echo | 35% (6/17) | 98% (181/184) |

93% (187/201) |

67% (6/9) | 94% (181/192) |

| Contrast Echo* | 64% (9/14) | 99% (174/176) |

96% (183/190) |

82% (9/11) | 97% (174/179) |

| Cine-CMR | 82% (14/17) | 100% (184/184) |

99% (198/201) |

100% (14/14) | 98% (184/187) |

Echo contrast administration deferred in 5% (n=11) due to product labeling contra-indications (e.g. decompensated heart failure, hypersensitivity) or patient refusal.

Figure 2. LV Thrombus Detection via DE-CMR Despite Negative Echocardiography.

Representative example of DE-CMR evidenced thrombus despite negative non-contrast (left) and contrast (right) echo. Note image artifact on non-contrast echo (arrow), which compromised endocardial definition and obscured LV cavity delineation. Contrast echo yielded improved image quality, but failed to detect mural thrombus in the LV apex (yellow circle; 4-chamber and short axis orientation shown).

Echo image quality was evaluated to determine whether technical factors varied in relation to performance of each echo approach. Table 5 compares prevalence of optimally scored echo image quality - including endocardial definition and absence of LV cavity artifacts - between echoes interpreted concordantly or discordantly with DE-CMR. Non-contrast echoes interpreted concordantly with DE-CMR more commonly had optimal overall image quality than did those discordant with DE-CMR (p=0.01), paralleled by higher prevalence of excellent endocardial definition (p=0.008) and absence of cavity artifacts (p=0.007). For contrast echo, diagnostic performance did not vary in relation to image quality, which was similar between exams concordant and discordant with DE-CMR (p=1.00).

Table 5.

Echo Image Quality in Relation to LV Thrombus Detection*

| Cumulative Image Quality | LV Cavity Artifacts | Endocardial Definition | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall Popula tion† |

Concor dant with DE- CMR |

Discor dant with DE- CMR |

P | Overall Popula tion |

Concor dant with DE- CMR |

Discor dant with DE- CMR |

P | Overall Popula tion |

Concor dant with DE- CMR |

Discor dant with DE- CMR |

P | |

| Non-Contrast Echo | 79.5% (159) |

81.7% (152) |

50.0% (7) |

0.01 | 85.6% (172) |

87.7% (164) |

57.1% (8) |

0.007 | 80.5% (161) |

82.8% (154) |

50.0% (7) |

0.008 |

| Contrast Echo | 86.3% (164) |

86.3% (158) |

85.7% (6) |

1.00 | 90.0% (171) |

90.2% (165) |

85.7% (6) |

0.53 | 93.2% (177) |

93.4% (171) |

85.7% (6) |

0.40 |

Data reported as % of patients with optimal echo image quality defined based on maximum cumulative image quality score as well as its constitutive parameters of endocardial definition and LV cavity artifacts. See text for details.

Echo Functional Parameters as a Gatekeeper for DE-CMR

LV functional parameters on echo were tested to determine whether they could effectively stratify those patients in need of further evaluation for thrombus via DE-CMR. Figure 3 provides ROC curves for non-contrast echo-derived EF and apical wall motion. As shown, apical wall motion score on non-contrast echo yielded improved overall performance compared to EF based on area under the curve (p=0.01). Apical wall motion score on contrast echo also yielded excellent performance (AUC = 0.89±0.44) in relation to DE-CMR evidenced thrombus.

Figure 3. Receiver Operating Characteristics Curves.

Apical LV wall motion score via non-contrast echo (red) yielded improved diagnostic performance compared to EF (blue), as evidenced by higher area under the curve (p=0.01).

Table 6 reports diagnostic performance of non-contrast and contrast echo using apical wall motion partitions necessary to provide perfect sensitivity (100% negative predictive value) for DE-CMR evidenced thrombus, together with maximal specificity. As shown, a non-contrast wall motion score of ≥5 would have enabled all patients with thrombus to be appropriately referred for DE-CMR, while avoiding unnecessary additional testing (via DE-CMR) in over half of the study population (56%; 112/201). A slightly higher partition for contrast echo (≥7) would have enabled identification of all patients with LV thrombus, while avoiding further testing via DE-CMR in a higher proportion of patients (63%; 120/190).

Table 6.

Diagnostic Performance of Echo-Based Wall Motion for LV Thrombus

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Non-Contrast Echo* | 100% (17/17) |

61% (112/184) |

64% (129/201) |

19% (17/89) | 100% (112/112) |

| Contrast Echo† | 100% (14/14) |

68% (120/176) |

71% (134/190) |

20% (14/70) | 100% (120/120) |

calculated using an apical wall motion score cutoff of ≥ 5

calculated using an apical wall motion score cutoff of ≥ 7

When further stratified based on angiography-evidenced infarct-related artery, positive predictive value of echo-based apical wall motion score was approximately 4-fold higher among patients with LAD culprit vessel MI (23%) compared to those with RCA or LCX (6%), paralleling higher prevalence of thrombus (15% vs. 1%).

Discussion

This study provides new data concerning performance of current imaging strategies, as well as utility of a novel approach – predicated on routine echo – for post-MI LV thrombus. Key findings are as follows: First, LV thrombus remains an important diagnostic issue in the current reperfusion era: Among the broad post-MI population studied, thrombus was present in 8% of all patients, including 15% of those with LAD infarction. Second, while generally associated with adverse remodeling, only 12% of patients with thrombus had markedly depressed EF (≤30%) on echo and only 18% had LV aneurysm. Third, despite tailored imaging with uniform contrast administration, echo remained limited as a solitary strategy for post-MI thrombus: Non-contrast echo yielded diagnostic sensitivity of 35% compared to the reference of DE-CMR. Whereas contrast improved echo image quality and sensitivity (64%), one third of DE-CMR evidenced thrombi were missed. Fourth, thrombus was strongly associated with regional LV dysfunction involving the apical LV: Altered patterns of volumetric and temporal contractility quantified by state-of-the-art cine-CMR segmentation were paralleled by echo assessment using routine visual wall motion scores. Echo-based wall motion partitions (selected to provide perfect sensitivity and optimized specificity) would have enabled all patients with thrombus to be appropriately referred for DE-CMR, while avoiding unnecessary additional testing (via DE-CMR) in over half (56–63%) of the population.

Our results extend upon prior research that has shown DE-CMR to improve LV thrombus detection compared to echo (1–5). Despite this advantage, CMR remains an impractical means of screening for thrombus in the ~500,000 Americans who sustain MI annually (19). In addition to its substantial costs, neither the equipment nor expertise required for CMR is widely available. Beyond technical considerations, the repeated breath-holds, supine positioning, and closed space environment typically required for CMR make this modality impractical for a substantial number of post-MI patients. Echo is inexpensive, widely available, and portable – facilitating its use as a screening tool for even critically ill patients. Our findings indicate that non-contrast echo can be used to effectively stratify post-MI patients with highest likelihood for thrombus, thereby allowing more sensitive evaluation via DE-CMR tissue characterization to be appropriately applied in high-risk cohorts while avoiding further testing in the majority of post-MI patients. Our observed strong association between LAD infarction and LV thrombus is consistent with echo studies conducted before widespread changes in post-MI revascularization. For example, among 8326 participants in the GISSI-3 study, thrombus was 5-fold more common with anterior wall MI (11.5% vs. 2.3%) (20). Based on this marked differential prevalence, it is tempting to use infarct-related artery as a primary means of stratifying those patients in whom dedicated thrombus imaging (contrast echo and/or DE-CMR) is most warranted. Applied clinically, our data indicate that if contrast echo were to be performed in all patients with LAD infarction and apical wall motion score used to stratify those in need of further testing, ~95% of all thrombi would be identified with use of DE-CMR in only ~20% of all post-MI patients. On the other hand, our study and prior research indicate that there is a small, albeit lesser, risk for thrombus among patients with non LAD infarction – a fact that should not be minimized in light of thrombus-associated risk for embolic events (6). Notably, in the one case of thrombus with non-LAD culprit vessel MI, adjunctive testing via ECG and echo demonstrated evidence of apical injury. In this context, further studies are warranted to determine whether cost effective tools such as ECG can augment echo-evidenced apical dysfunction, so as to better identify patients in whom DE-CMR yields greatest incremental utility (over conventional post-MI testing) for LV thrombus.

The majority of prior CMR studies that have examined LV thrombus have done so in mixed cohorts or in patients with chronic heart failure (1,2,4–6). To the best of our knowledge, only one study used CMR to examine LV thrombus in an exclusively post-MI cohort (5): However, DE- and cine-CMR were interpreted together, regional LV contractility was not quantified, and thrombus location was not reported – thereby resulting in knowledge gaps as to imaging and pathophysiology of post-MI thrombus. Whereas DE-CMR has been used to study thrombus in patients with systolic dysfunction (2–4), our findings demonstrate that substantial differences exist regarding thrombus in the post-MI compared to the chronic heart failure setting. Regarding distribution, all thrombi in this post-MI cohort were apical in location. In our prior study of patients with systolic dysfunction, prevalence of thrombus was similar (7%) to the current study (8%), but 20% of thrombi were non-apical in location (within basal or mid LV) (6). Similarly, among heart failure patients undergoing LV reconstruction surgery, Srichai et al. reported that 29% of thrombi were located outside the LV apex (4). Possible reasons for differences in thrombus distribution relate to variability in LV remodeling and/or contractile dysfunction between patients with chronic heart failure versus those with acute MI.

It is important to note that LV thrombus can occur in the absence of severely impaired LVEF, as evidenced by the fact that 8% of all patients had thrombus but only 2% had LVEF ≤ 30%. This may relate to the fact that apical dysfunction can be profound despite preserved global LV function. Regarding spatial distribution, our cine-CMR results shed light on mechanisms responsible for apical thrombus. Regional contractile parameters increased in magnitude between patients with and without thrombus - magnitude of difference increased with progression from the basal to apical LV. Consistent with this, prior studies using animal models have shown LAD infarction to acutely alter apical blood flow (21). It is possible that regional differences in contractile function, combined with pro-thrombotic alterations induced by myocardial necrosis, may explain the link between MI and apical thrombus. Notably, our results demonstrate that differences in contractile function related to thrombus are discernable on both advanced cine-CMR and routine echo analyses. Further studies are warranted to test whether quantitative assessment of apical blood flow (combined with measures of infarct distribution) can further stratify risk for thrombus, thereby facilitating targeted strategies to detect or prevent LV thrombus.

One limitation concerns the fact that our sample size – particularly the small number of positive cases in this single center cohort – prohibits comprehensive multivariate analysis concerning LV thrombus. Importantly, prevalence of post-MI LV thrombus in our study (8%) is similar to prior multicenter CMR data (8.8%) (5) – supportive of the notion that our findings are broadly reflective of post-MI LV thrombus in the current era. It is also important to recognize that imaging for this study was performed at a target of 1 month post-MI, a time point selected based on prior echo data (22). More recent CMR research has shown that LV thrombus can be present early post MI and self-resolve thereafter (5). It is certainly possible that some patients in our cohort could have had LV thrombus that resolved by 1 month post-MI.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that LV thrombus remains an important consideration in post-MI patients, which can occur even in the absence of aneurysm or advanced LV dysfunction. Whereas DE-CMR tissue characterization yields improved detection of post-MI thrombus, echo – analyzed in a routine manner for apical wall motion – can be used as an effective stratification tool to identify patients in whom thrombus assessment via DE-CMR is most warranted.

Clinical Perspectives.

Competency in Medical Knowledge

Among a broad cohort of acute MI patients, LV thrombus was present on DE-CMR in 8%, was strongly related to LAD infarction, and often occurred in the absence of LV aneurysm. While echo yielded limited diagnostic performance for LV thrombus, apical wall motion score as assessed via echo effectively stratified need for further testing for thrombus via DE-CMR.

Translational Outlook

Additional studies are needed to further validate current findings in larger multicenter cohorts, as well as to compare DE-CMR thrombus detection to echo-based apical wall motion score for thrombo-embolic risk stratification following acute MI.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award, NIH K23 HL102249-01, Lantheus Medical Imaging (JWW).

Abbreviations

- MI

myocardial infarction

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- EF

ejection fraction

- Echo

echocardiography

- LV

left ventricle

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

area under the curve

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests Disclosure: This work was partially funded through a research grant provided by Lantheus Medical Imaging (echo contrast product manufacturer).

CLINICAL TRIAL: Diagnostic Utility of Contrast Echocardiography for Detection of LV Thrombi Post ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00539045?term=NCT00539045&rank=1, NCT00539045

References

- 1.Weinsaft JW, Kim RJ, Ross M, et al. Contrast-enhanced anatomic imaging as compared to contrast-enhanced tissue characterization for detection of left ventricular thrombus. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:969–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinsaft JW, Kim HW, Crowley AL, et al. LV thrombus detection by routine echocardiography: insights into performance characteristics using delayed enhancement CMR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:702–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mollet NR, Dymarkowski S, Volders W, et al. Visualization of ventricular thrombi with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2873–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044389.51236.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srichai MB, Junor C, Rodriguez LL, et al. Clinical, imaging, and pathologic characteristics of left ventricular thrombus: A comparison of contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, transthoracic echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography with surgical or pathological validation. American Heart Journal. 2006;152:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delewi R, Nijveldt R, Hirsch A, et al. Left ventricular thrombus formation after acute myocardial infarction as assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. European journal of radiology. 2012;81:3900–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinsaft JW, Kim HW, Shah DJ, et al. Detection of left ventricular thrombus by delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance prevalence and markers in patients with systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:148–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang RM, Biereg M, Devereux RM, et al. Recommendations for Chamber Quantification: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, Developed in Conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a Branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinsaft J, Kim H, Shah DJ, et al. Detection of Left Ventricular Thrombus by Delayed-Enhancement CMR: Prevalence and Markers in Patients with Systolic Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:148–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asinger RW, Mikell FL, Elsperger J, Hodges M. Incidence of left-ventricular thrombosis after acute transmural myocardial infarction. Serial evaluation by two-dimensional echocardiography. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:297–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108063050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sievers B, Elliott MD, Hurwitz LM, et al. Rapid detection of myocardial infarction by subsecond, free-breathing delayed contrast-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2007;115:236–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Palmieri V, et al. Prognostic implications of ejection fraction from linear echocardiographic dimensions: the Strong Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2003;146:527–34. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stratton JR, Lighty GW, Jr, Pearlman AS, Ritchie JL. Detection of left ventricular thrombus by two-dimensional echocardiography: sensitivity, specificity, and causes of uncertainty. Circulation. 1982;66:156–66. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawaji K, Codella NC, Prince MR, et al. Automated segmentation of routine clinical cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:476–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.879304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Codella NC, Cham MD, Wong R, et al. Rapid and accurate left ventricular chamber quantification using a novel CMR segmentation algorithm: a clinical validation study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:845–53. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Codella NC, Weinsaft JW, Cham MD, Janik M, Prince MR, Wang Y. Left ventricle: automated segmentation by using myocardial effusion threshold reduction and intravoxel computation at MR imaging. Radiology. 2008;248:1004–12. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2482072016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction–executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1999 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:671–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiarella F, Santoro E, Domenicucci S, Maggioni A, Vecchio C. Predischarge two-dimensional echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular thrombosis after acute myocardial infarction in the GISSI-3 study. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:822–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikell FL, Asinger RW, Elsperger KJ, Anderson WR, Hodges M. Regional stasis of blood in the dysfunctional left ventricle: echocardiographic detection and differentiation from early thrombosis. Circulation. 1982;66:755–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.4.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kupper AJ, Verheugt FW, Peels CH, Galema TW, Roos JP. Left ventricular thrombus incidence and behavior studied by serial two-dimensional echocardiography in acute anterior myocardial infarction: left ventricular wall motion, systemic embolism and oral anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:1514–20. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]