Abstract

Introduction

Beginning in the late 1970s, a very sharp decline in cigarette smoking prevalence was observed among African American (AA) high school seniors compared with a more modest decline among whites. This historic decline resulted in a lower prevalence of cigarette smoking among AA youth that has persisted for several decades.

Methods

We synthesized information contained in the research literature and tobacco industry documents to provide an account of past influences on cigarette smoking behavior among AA youth to help understand the reasons for these historically lower rates of cigarette smoking.

Results

While a number of protective factors including cigarette price increases, religiosity, parental opposition, sports participation, body image, and negative attitudes towards cigarette smoking may have all played a role in maintaining lower rates of cigarette smoking among AA youth as compared to white youth, the efforts of the tobacco industry seem to have prevented the effectiveness of these factors from carrying over into adulthood.

Conclusion

Continuing public health efforts that prevent cigarette smoking initiation and maintain lower cigarette smoking rates among AA youth throughout adulthood have the potential to help reduce the negative health consequences of smoking in this population.

Implications

While AA youth continue to have a lower prevalence of cigarette smoking than white youth, they are still at risk of increasing their smoking behavior due to aggressive targeted marketing by the tobacco industry. Because AAs suffer disproportionately from tobacco-related disease, and have higher incidence and mortality rates from lung cancer, efforts to prevent smoking initiation and maintain lower cigarette smoking rates among AA youth have the potential to significantly lower lung cancer death rates among AA adults.

Introduction

The current prevalence of cigarette smoking is similar among African American (AA) and white adults at approximately 18%1; however; AAs historically have had a cumulative lower consumption of cigarettes than whites. For example, AA youth persistently have had lower rates of cigarette smoking since the late 1970s in comparison to white youth.2–4 A similar trend has been observed among AA young adults.3 AAs also initiate cigarette smoking at a later age than whites.2,4 Despite these differences in cigarette smoking behavior between AAs and whites, AAs suffer disproportionately from tobacco-related disease and death and have higher incidence and mortality rates from lung cancer compared to whites.2,5–9

While there are other potential causes of the disparity in lung cancer risk among AAs (eg, socioeconomic status, environmental exposures, genetics, and access to diagnosis and treatment),8 nearly all cases of lung cancer are attributable to cigarette smoking.7–9 For this reason, it will be important to understand how to maintain lower cigarette smoking in AA youth throughout adulthood to help reduce the negative health consequences of smoking in this population.

To shed light on measures that can be taken to maintain these lower rates, this brief report will provide an overview of past influences of cigarette smoking behavior among AA youth.

Methods

Information for this brief report was synthesized from the research literature and tobacco industry documents to provide an overview of possible factors that contributed to the rapid decline in cigarette smoking that occurred among AA youth starting in the late 1970s until the early 1980s, and the reversal of this trend beginning in the 1990s. The tobacco industry documents were retrieved from the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (LTDL), University of California, San Francisco. The following search terms were used to search the tobacco industry documents: AA youth, AA youth marketing, Black youth, marketing to Black youth, menthol marketing, AA menthol marketing, and menthol cigarette campaigns.

Results

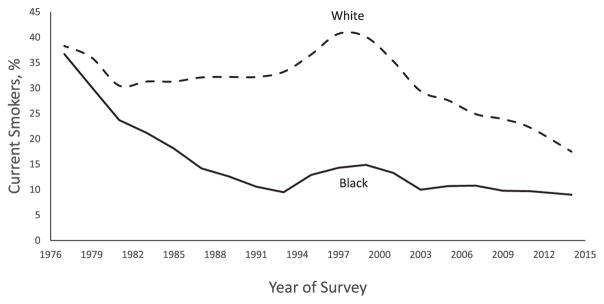

While a number of protective factors including cigarette price increases, religiosity, parental opposition, sports participation, body image, and negative attitudes towards cigarette smoking may have all played a role in maintaining lower rates of cigarette smoking among AA youth as compared to white youth (Figure 1), the efforts of the tobacco industry seem to have prevented the effectiveness of these factors from carrying over into adulthood.

Figure 1.

Trends in prevalence of past month cigarette smoking among high school seniors by race—United States, 1977–2014.

History of Youth Cigarette Smoking in the United States

Beginning in the mid-1970s in the United States, the cigarette smoking prevalence for both AA and white high school seniors was similar at approximately 40%.10 This trend began to change during the late 1970s to early 1980s, when cigarette smoking prevalence among both groups started to decline; however, this decline occurred much faster among AA students.3,4 While the decline that occurred among white youth stabilized in the early 1980s, the decline among AA youth continued until the early 1990s3,10; this decline was even more striking among AA female youth.10

However, in the early 1990s, the decline in cigarette smoking among both AA and white youth started to reverse. From 1991 to 1997, current cigarette smoking increased among both AA and white youth.4,11–13 While the cigarette smoking prevalence among AA youth remained lower than whites, the magnitude of the increase was much greater among AA youth (particularly males) during this time period,13 with research showing the prevalence of cigarette smoking among AA youth almost doubling from 12.6% in 1991 to 22.7% in 1997.13,14 Cigarette smoking prevalence started to decline again in the late 1990s, but the rate of decline began to slow down in 2003 for both AA and white youth. Since 2003, the rate of decline in current cigarette smoking slowed or leveled off for both AA and white youth.3,13

Influence of Protective Factors

Multiple protective factors appear to be responsible for the sharper decline in cigarette smoking prevalence that occurred in the late 1970s and continued until the early 1990s among AA youth.3,4,15 One important factor that has been identified as being especially impactful on AA youth smoking behavior is cigarette price increases.10,16 Cigarette prices have risen dramatically over the years since the late 1970s.4,17 Younger AA smokers are more responsive to price increases and are more likely than white smokers to reduce or quit smoking in response to a price increase.16

Another factor that could have contributed to lower cigarette smoking prevalence among AA youth during this time period is religiosity. The Black church historically has played an important role in the health of AAs.15 Religion has been found to be a stronger protective factor against smoking among AA youth compared with whites.4,15 AA youth attribute more importance to religion in their lives, and have a higher frequency of church attendance and involvement in religious activities than white youth.4 Increased religiosity among AA youth is probably largely due to parental influence.4 Parental opposition to cigarette smoking in AA households may have also played a role in curtailing the uptake of cigarette smoking among AA youth.18 Moreover, negative attitudes toward cigarette smoking have been generally held by AA youth, their peers, and the community as a whole.4

Often overlooked in assessing the protective factors against cigarette smoking among AA youth is the role of high school sports. Davis and colleagues found that AA male high school athletes were less likely to use tobacco compared to white male high school athletes.19 In addition, they found that AAs involved in high-intensity sports were less likely to be heavy smokers than those participating in low intensity sports.19 This is consistent with what Gardiner observed in his review of AA teen smoking; that is, many young AA males see participation in football, basketball, and track and field (high-intensity sports) as a means toward future employment and avenues for escaping depressed inner cities.15

Tobacco Industry Influence

Because tobacco industry marketing has been pervasive in AA communities for several decades, tobacco industry marketing may have played a major role in the larger increase in cigarette smoking prevalence that occurred among AA youth in the 1990s. For example, from 1992 to 1998, there was a 31% increase in cigarette smoking prevalence among white high school seniors compared to a 71% increase among AA high school seniors (Figure 1). This more marked increase in the prevalence of cigarette smoking among AA youth may reflect the increased targeted marketing to this population by the tobacco industry to establish the AA youth market during the “menthol wars” of the 1980s.20 The “menthol wars” were waged in inner city communities where the major tobacco companies (ie, Lorillard, Brown and Williamson, Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds) dispatched company vans to give away free cigarettes in high traffic areas including community parks and street corners.20 By the 1990s, the tobacco industry launched additional campaigns specifically targeted to AA youth. For example, the Marlboro Menthol Inner City Black Bar Program, developed in the late 1980s, expanded in the 1990s and included games, giveaways, and amateur Marlboro Music talent contests.21 In 1990, RJ Reynolds test-marketed Uptown menthol cigarettes in Philadelphia with the slogan “the uptown flavor with the downtown price” and sponsored several cultural and inner-city nightclub events with free pack giveaways. The Uptown theme focused on style, music, nightlife, and entertainment and was specifically targeted to the AA community.22,23 Community anti-tobacco advocates formed a coalition to block the marketing of Uptown cigarettes. As a result of this public pressure, RJ Reynolds withdrew this product from the market.24,25

The Fat Boys campaign, a Black inner city targeted brand, was launched by RJ Reynolds in the early 1990s.26 The Fat Boys campaign focused on the “environment and interests of inner-city Blacks” as well as rap music. The product packaging had a brick wall and graffiti design. Advertising for the product featured young AA males that strongly resembled leading characters of the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air—a popular 1990s sitcom that appealed to many urban youth.26 Like Uptown, Fat Boys were mentholated and available in packages of 10 to address price sensitivity for AA smokers.26

During Black History Month in 1995, Menthol X cigarettes were launched by Stowebridge Brook Distributors in stores around Massachusetts.27 This “new Black brand” featured red, black, and green colors, representing the Black liberation colors and displayed a large “X” on the front of the pack, a symbol that gained popularity after the 1992 movie Malcolm X debuted. During the late 1990s, Brown and Williamson’s B KOOL campaign featured “House of Menthol” promotions including playing cards featuring young, hip AAs, and concerts and music events at AA bars and nightclubs.28 Even though tobacco control advocacy efforts in the AA community were successful in curtailing or stopping some of the tobacco industry activities (eg, Uptown and Menthol X), AA youth cigarette smoking rates still rose starkly in the 1990s.

The steeper decline in the prevalence of cigarette smoking observed among white youth during the late 1990s may have been the result of the enactment of the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement. As part of the Master Settlement Agreement between the state Attorneys General of 46 states, five US territories, the District of Columbia and the major US cigarette companies, both indirect and direct tobacco advertising targeting youth were prohibited. The types of targeted advertising that were restricted included advertising on billboards as well as advertising on or around public transit, stadiums, arenas, shopping malls, and video arcades.29

While the Master Settlement Agreement banned tobacco advertising in certain media outlets and venues that are highly noticeable by youth, it did not restrict outdoor or indoor advertising at the point-of-sale (POS) on retailer property.29 An overwhelming body of evidence has shown that tobacco advertising influences youth to initiate cigarette smoking as well as to continue its use, and that there is a positive association between exposure to POS tobacco promotion and increased smoking.10,30–33 Exterior signage and interior POS advertising for tobacco products are especially pervasive in AA neighborhoods, particularly advertisements for mentholated cigarette brands. For example, several reports have documented how the tobacco industry has aggressively targeted the marketing of menthol cigarettes to AAs through placement of large numbers of interior and exterior signs in low income, AA communities.34–37

Tobacco retail advertising at the POS encourages youth to smoke,30–33 and there is more POS advertising in predominately AA communities.32,36–38 Therefore, differential exposure to in-store marketing might have contributed to the different trends in cigarette smoking prevalence observed among white and AA youth. The protective factors that may have contributed to the larger decline in smoking among AA youth in the late 1970s and early 1980s might have lost some of their impact due in large part to more aggressive and effective tobacco industry marketing practices targeted toward this population.

Conclusion

The protective factors that may have kept cigarette smoking among AA youth significantly lower than whites seem to not carry over into adulthood as cigarette smoking prevalence rapidly rises among AA adults to be similar to that of whites.1 This “great leap forward” may be also attributed to the targeted marketing of AA adults by the tobacco industry.20 The persistent targeted marketing to the AA community by the tobacco industry promoting menthol cigarettes and other flavored products10,28,30,33,35,39 emphasize the importance of tobacco prevention and control efforts in countering this targeted marketing to help reduce the negative health consequences of smoking in this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr Pechacek receives unrestricted support from Pfizer, Inc. (“Diffusion of Tobacco Control Fundamentals to Other Large Chinese Cities” - Michael Eriksen, Principal Investigator).

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Stacy Thorne and Ms Brandi Martell at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Office on Smoking and Health for their technical assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions are the author’s, not necessarily the CDC’s.

Supplement Sponsorship

This article appears as part of the supplement “Critical Examination of Factors Related to the Smoking Trajectory among African American Youth and Young Adults,” sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention contract no. 200-2014-M-58879.

References

- 1.Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. [Accessed July 7, 2015];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 63(47):1108–1112. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6347a4.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. [Accessed July 7, 2015]. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson DE, Mowery P, Asman K, et al. Long-term trends in adolescent and young adult smoking in the United States: metapatterns and implications. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5):905–915. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oredein T, Foulds J. Causes of the decline in cigarette smoking among African American youths from the 1970s to the 1990s. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):e4–e14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2013–2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):333–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial/Ethnic disparities and geographic differences in lung cancer incidence—38 States and the District of Columbia, 1998–2006. [Accessed July 7, 2015];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 59(44):1434–1438. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5944a2.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Lung Association. Too Many Cases, Too Many Death: Lung Cancer in African Americans. Washington, DC: American Lung Association; 2010. [Accessed July 7, 2015]. www.lung.org/assets/documents/publications/lung-disease-data/ala-lung-cancer-in-african.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Center MM, Ward E. The convergence of lung cancer rates between blacks and whites under the age of 40, United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(12):3349–3352. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2012. [Accessed July 9, 2015]. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2012/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson DE, Giovino GA, Shopland DR, Mowery PD, Mills SL, Eriksen MP. Trends in cigarette smoking among US adolescents, 1974 through 1991. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(1):34–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM. Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use: racial and ethnic differences among U.S. high school seniors, 1976–2000. [Accessed July 9, 2015];Public Health Rep. 2002 117(suppl 1):S67–75. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1913705/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention. Cigarette use among high school students—United States, 1991–2009. [Accessed July 9, 2015];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 59(26):797–801. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5926a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mermelstein R. Ethnicity, gender and risk factors for smoking initiation: an overview. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(suppl 2):S39–43. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011791. discussion S69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardiner PS. African American teen cigarette smoking: a review. Changing adolescent smoking prevalence: where it is and why. [Accessed July 10, 2015];Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph. 2001 (14):213–226. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/Brp/tcrb/monographs/14/m14_14.pdf.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Response to increases in cigarette prices by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups—United States, 1976–1993. [Accessed July 9, 2015];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998 47(29):605–609. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9699809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Trends in adolescent smoking initiation in the United States: is tobacco marketing an influence? Tob Control. 1997;6(2):122–127. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skinner ML, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Parental and peer influences on teen smoking: Are White and Black families different? Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(5):558–563. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis TC, Arnold C, Nandy I, et al. Tobacco use among male high school athletes. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21(2):97–101. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(suppl 4):10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menthol—Event Sponsorship Marlboro Menthol Inner City Bar Nights. Philip Morris; 1989. [Accessed July 10, 2015]. https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=hzbw0125. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkins SC, Reynolds RJ. Project Ut Creative Qualitative Research. Salem, NC: Marketing Research Department, RJ Reynolds; 1989. [Accessed July 10, 2015]. http://legacy-dc.ucsf.edu/tid/ipf63a00/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds RJ. [Accessed July 10, 2015];Q&A for Leave Behind. 1989 http://legacy-dc.ucsf.edu/tid/gcv61d00/pdf;jsessionid=FC2D28586E9D0DE65CF9A8525F5B2002.tobacco03.

- 24.Robinson RG, Pertschuk M, Sutton C. Smoking and African Americans: spotlighting the effects of smoking and tobacco prevention in the African American Community. In: Samuels SE, Smith M, editors. Improving the Health of the Poor: Strategies for Prevention. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 1992. pp. 123–181. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yerger VB, Malone RE. African American leadership groups: smoking with the enemy. Tob Control. 2002;11:336–345. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.1990 New Marketing Ideas. Joe Camel; Mangini Lawsuit: 1989. [Accessed July 10, 2015]. https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=hfdv0095. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Los Angeles Times. [Accessed August 31, 2015];Maker of Menthol X Agrees to Pull It After Protests. 1995 https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qklm0085.

- 28.Hafez N, Ling PM. Finding the Kool Mixx: how Brown & Williamson used music marketing to sell cigarettes. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):359–366. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Settling States and Participating Manufacturers. [Accessed May 24, 2015];Master Settlement Agreement. 1998 www.naag.org/naag/about_naag/naag-center-for-tobacco-and-public-health/master-settlement-agreement/master-settlement-agreement-msa.php?

- 30.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Cowling DW, Kline RS, Fortmann SP. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Prev Med. 2008;47(2):210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):232–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, Hoek J. A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(1):2–17. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardiner PS. The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(suppl 1):S55–65. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz TB, Wright LT, Crawford G. The menthol marketing mix: targeted promotions for focus communities in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl 2):S147–153. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidenberg AB, Caughey RW, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Storefront cigarette advertising differs by community demographic profile. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24(6):e26–31. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090618-QUAN-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Dauphinee AL, Fortmann SP. Targeted advertising, promotion, and price for menthol cigarettes in California high school neighborhoods. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):116–121. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyland A, Travers MJ, Cummings KM, Bauer J, Alford T, Wieczorek WF. Tobacco outlet density and demographics in Erie County, New York. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1075–1076. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Accessed July 7, 2015]. www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/index.html. [Google Scholar]