Abstract

Introduction

Comprehensive tobacco prevention and control efforts that include implementing smoke-free air laws, increasing tobacco prices, conducting hard-hitting mass media campaigns, and making evidence-based cessation treatments available are effective in reducing tobacco use in the general population. However, if these interventions are not implemented in an equitable manner, certain population groups may be left out causing or exacerbating disparities in tobacco use. Disparities in tobacco use have, in part, stemmed from inequities in the way tobacco control policies and programs have been adopted and implemented to reach and impact the most vulnerable segments of the population that have the highest rates of smokings (e.g., those with lower education and incomes).

Methods

Education and income are the 2 main social determinants of health that negatively impact health. However, there are other social determinants of health that must be considered for tobacco control policies to be effective in reducing tobacco-related disparities. This article will provide an overview of how tobacco control policies and programs can address key social determinants of health in order to achieve equity and eliminate disparities in tobacco prevention and control.

Results

Tobacco control policy interventions can be effective in addressing the social determinants of health in tobacco prevention and control to achieve equity and eliminate tobacco-related disparities when they are implemented consistently and equitably across all population groups.

Conclusions

Taking a social determinants of health approach in tobacco prevention and control will be necessary to achieve equity and eliminate tobacco-related disparities.

Introduction

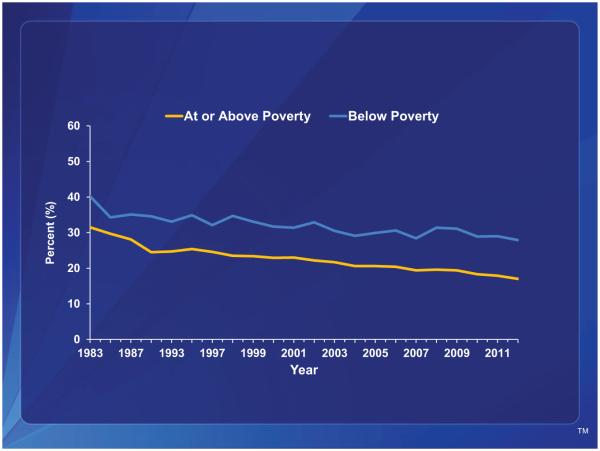

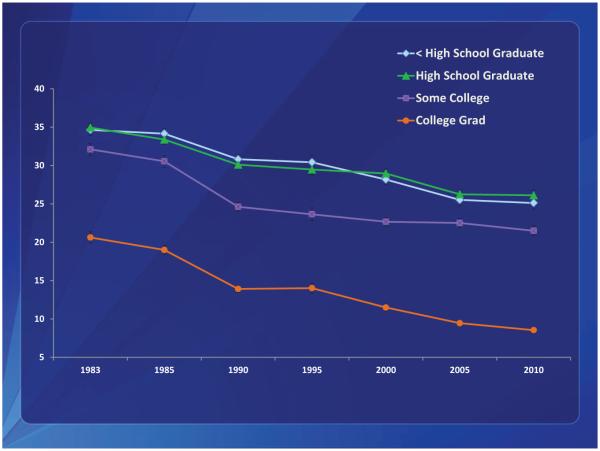

A combination of synergistic public health efforts have led to significant declines in smoking prevalence for the general population.1 Data from multiple surveys have documented that the Healthy People 2020 goal of reducing smoking prevalence to less than 12% has been achieved or exceeded for some population groups; for example, those with higher education and incomes. Unfortunately, progress in reducing smoking prevalence has been markedly slower among populations of low socioeconomic status (SES) as characterized by low incomes, low levels of education, unemployment, and blue-collar and service industry workers.2,3 This has resulted in a widening of the disparity in cigarette smoking between low- and high-SES smokers (Figures 1 and 2). To be successful in achieving further declines in national smoking prevalence, eliminating disparities in cigarette smoking, particularly among populations with low SES, will be necessary.

Figure 1.

Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years, by poverty status—United States, 1983–2012, National Health Interview Survey.

Figure 2.

Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years, by educational status—United States, 1983–2010, National Health Interview Survey.

While low SES is a powerful determinant of smoking behavior and predominantly accounts for the disparities in tobacco use within the general population, low SES also interacts with a complex array of other factors to influence smoking behavior. These factors can include race/ethnicity, cultural characteristics, acculturation, social marginalization (e.g., Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender communities, people with mental illness and substance abuse disorders), stress, tobacco industry influence, lack of comprehensive tobacco control policies, and lack of community empowerment.4 These determinants of smoking behavior can also be described within a larger environmental and social context called the Social Determinants of Health (SDH). The World Health Organization (WHO) has described the SDH “as the circumstances in which people grow, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. These conditions in which people live and die are, in turn, shaped by political, social and economic forces, and are characterized by the unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services; unequal access to healthcare, schools, and education; and conditions in work and leisure settings, homes, communities, towns, or cities.”5 These determinants and their distribution in society interact in unique ways to impact health disparities by limiting the ability of many population groups to achieve health equity. For this reason, a new social determinants vision for Healthy People 2020 has established a new overarching goal to “create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.”6

Addressing the SDH will be critical in achieving equity and eliminating disparities in tobacco prevention and control. However, addressing education and poverty in order to reduce disparities in tobacco use is probably not feasible as doing so would require fundamental social change and is not within the traditional practice of tobacco control.7 While low education and income are the main SDH that can determine increased tobacco use, other related SDH such as the unequal distribution of resources, power, and services can also lead to inequities in tobacco prevention and control and subsequent disparities in tobacco use. These determinants include the unequal distribution of resources for tobacco control and limited access to health care services, including limited access to evidence-based cessation treatments and services.

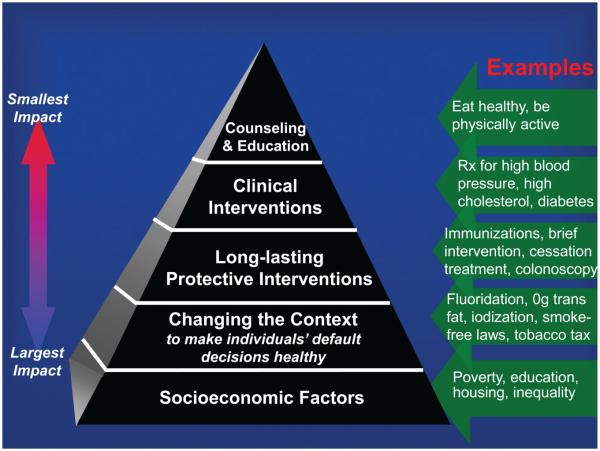

While social and economic conditions (e.g., poverty, education, and the unequal distribution of resources, power, and services) have the greatest impact on public health and associated risk factors such as smoking,7 changing the environmental context is probably the most important SDH that can be readily addressed in tobacco control to achieve equity and eliminate disparities. WHO has characterized this SDH as “where people grow, live, work and age and also the conditions in work and leisure settings, homes, communities, towns, or cities.”5 This environmental context has also been described by Frieden7 in his public health framework using a 5-tier health impact pyramid (Figure 3). The second tier of the pyramid represents interventions that change the environmental context to make healthy options the default choice so that they will eventually become the normal choice. In other words, these default healthy choices could lead to social norm changes in behavior. One of the main mechanisms through which evidence-based tobacco control interventions bring about behavioral change is by changing social norms. These interventions can discourage tobacco use by making it socially unacceptable. For example, like a disease, smoking cessation may be “contagious” in community clusters of smokers, moving quickly through a community or social network in a ripple effect once a few smokers quit, demonstrating how shifts in social norms may occur.8

Figure 3.

The health impact pyramid. Adapted from: Frieden.7

Other examples in tobacco control for creating healthier environmental contexts include implementing smoke-free laws and taxing tobacco products.7 Findings show that lower-income communities may be less likely to adopt local smoke-free laws,9 and service and blue-collar employees may be less likely to be protected by legislated or voluntary smoke-free workplace policies.10,11 These are the populations that have the highest prevalence of smoking2,3 and secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure.12–14 While changing the environmental context to bring about social norm changes has proven to be effective, it is important that this approach does not lead to stigmatization of smokers who belong to groups that are already marginalized.15 Nevertheless, in order for tobacco control interventions to be equitable and to realize their full potential, they need to be implemented in ways that offer all populations the opportunity to experience changes in social norms that have proven to be instrumental in reducing the burden of tobacco use.

Establishing a health equity framework for tobacco prevention and control that allows for the equal distribution of tobacco control programs and policies would provide all population groups with the opportunity to receive proven interventions for reducing tobacco use, thus achieving equity and eliminating disparities. This will require taking steps to ensure that tobacco control programs and policies are implemented in a consistent and equitable manner. Such steps would require targeted education toward all affected population groups and involving them in the process of planning the adoption and implementation of these interventions as early as possible. The following sections of this paper will describe a concept for how a SDH approach in tobacco control can effectively achieve equity and eliminate tobacco-related disparities by changing the environmental context through the equitable adoption and implementation of tobacco control policies and programs.

Achieving Equity and Eliminating Tobacco-Related Disparities

Population-based tobacco control interventions are optimally effective when they are implemented within the context of a comprehensive tobacco control program. These interventions include increasing the unit price of tobacco products, implementing smoke-free laws, restricting tobacco promotion, conducting hard-hitting mass media campaigns, and making evidence-based cessation treatments accessible for smokers who try to quit in response to these interventions or other influences.16 However, if these interventions are not fully implemented to reach and impact all population groups equally, they have the potential to exacerbate existing disparities or create new ones. On the other hand, tobacco control policies and programs can change social norms regarding tobacco use by changing the time, place and manner (i.e., environmental context) in which tobacco products are marketed, sold, and consumed in ways that make tobacco products and tobacco use less appealing, available, and acceptable. Using this SDH approach, the following tobacco control interventions have the potential to advance equity and eliminate disparities if they are indeed implemented in a consistent and equitable manner.

Comprehensive Smoke-Free Air Laws

Comprehensive smoke-free air laws protect nonsmokers from SHS exposure by banning smoking in workplaces, restaurants, and bars. This policy intervention has the added benefit of motivating and helping smokers to quit, as well as contributing to changes in social norms around the acceptability of smoking. For example, the prevalence of private smoke-free household rules increases in jurisdictions that have comprehensive public smoke-free laws.17

As with smoking prevalence, there have been significant declines in SHS exposure among the general population; however, disparities in exposure persist including populations living below the federal poverty level.13 It has been reported that people from all socioeconomic backgrounds can benefit from comprehensive smoke-free air laws.14,18 However, all population groups are not protected equally. Protecting all population groups equally from SHS exposure can change environmental and social conditions that can influence tobacco use. The best way to protect all population groups equally is to eliminate smoking in all indoor spaces.14 In addition to implementing 100% smoke-free policies in workplaces, restaurants, and bars, prohibiting smoking in other settings where large numbers of low-SES populations can be reached will also be important in changing social norms, reducing SHS exposure, and increasing cessation in these groups. This could include implementing smoke-free policies in public and private multiunit housing facilities and homeless shelters, as well as implementing tobacco-free campus policies in mental health and substance abuse treatment facilities.19–21

Tobacco Price Increases Coupled With Affordable Cessation Services

Making smoking and the use of tobacco products less affordable by increasing the price of tobacco can significantly reduce tobacco use. Scientific studies have shown that this policy intervention can discourage initiation among youth and young adults, increase cessation among adults, and reduce consumption among those who continue to smoke.22 However, when implementing this approach, it will be important to seek to minimize the potential unintended consequence of regressivity among low-income smokers. On the one hand, because low-income smokers are more price-sensitive, they may be more likely to quit in response to price increases. On the other hand, they may lack insurance coverage for evidence-based cessation treatment and may be unable to afford or access these treatments if they are unable to quit on their own. Low-income smokers who continue to smoke after a price increase will be more impacted by a price increase than higher-income smokers, since they will spend a larger proportion of their incomes on cigarettes than higher-income smokers.

To address this issue, it will be beneficial to couple policies that increase the price of tobacco products with the provision of increased comprehensive tobacco control program activities, including accessible, evidence-based cessation services targeted to low-income populations, as well as increased tobacco education campaigns.22 If implemented in this manner, tobacco price increases have the potential to improve a community’s situation by freeing up income that would have otherwise been spent on tobacco products and tobacco-related medical costs. Unfortunately, revenue from most tobacco tax increases over the past decade has been used to benefit non-tobacco control efforts, and sometimes with simultaneous decreases in tobacco control programs.22

Hard-Hitting Mass Media Campaigns

For many decades, the tobacco industry has targeted the marketing of tobacco products to low-income and minority communities, including especially high levels of advertising, promotion and discounts, particularly at the point-of-sale.23–25 For example, poor and minority neighborhoods often have higher density of tobacco retailers and point-of-sale advertising.26–28 This type of industry behavior has helped to create and perpetuate disparities in tobacco use by creating environmental conditions that increase a community’s vulnerability to smoking initiation and impede smoking cessation.4

In addition to targeted marketing by the tobacco industry, higher smoking prevalence and lower quit rates among minority and low-SES smokers may be explained in part by these smokers having less exposure and access to meaningful information about the harms of smoking, thus making them more vulnerable to the promotional activities of the tobacco industry. Well-designed mass media campaigns have the potential to counter industry marketing, increase awareness of the health effects of tobacco use and SHS exposure, and change environmental conditions that encourage people to smoke.

While it has been shown that large antitobacco media campaigns can reduce smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption and increase quit rates among the general population,22,28 a growing body of literature suggests that not all antitobacco media campaigns that promote cessation are appealing to low-SES populations.29 A number of studies have found that ads featuring emotional/personal testimonies and graphic images of the health effects of tobacco that evoke strong negative emotions are more likely to be effective in promoting smoking cessation among low-SES populations in comparison to ads that solely provide information on how to quit without the use of testimonials.29–31

Because variations in smoking prevalence between SES groups may stem from differences in the understanding of the health hazards of smoking and differences in receptivity to smoking-related health messages among low-SES populations,32 it will be important to develop mass media campaigns that convey graphic, emotional, and personal testimonies that arouse emotions to increase responsiveness to antitobacco messages and in a way that is easy to interpret and understand.30

Sustained Tobacco Control Program Funding

As stated above, WHO has characterized the SDH, in part, as “the unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services….”5 Therefore, a community’s capacity for implementing comprehensive tobacco control programs and policies to change the environmental context to influence social norm changes will largely depend on sustainable funding and capacity. A community’s level of social capital and social cohesion can influence tobacco use behavior, determine level of SHS exposure, and the ability to successfully quit.33 A 2007 Institute of Medicine Report and the 2014 CDC Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs16 both state that in order to end the tobacco use epidemic, states will need to fully implement evidence-based tobacco control programs that are comprehensive, sustainable, and accountable. In addition to a state-based approach, moving towards eliminating tobacco-related disparities and achieving equity will require increasing the capacity of community-based organizations to positively influence changes in social norms around tobacco use and building relationships between health departments and grassroots efforts.4,16 Ensuring sustainability will also require empowering local agencies to build community coalitions and facilitating collaborations among local government bodies, voluntary and civic organizations, and diverse community-based organizations.

Conclusion

Taking a SDH approach in tobacco prevention and control (i.e., changing the environmental context and ensuring the equal distribution of resources and services) will be necessary to achieve equity and eliminate tobacco-related disparities. Tobacco control policy interventions have the potential to address these conditions; however, this will not happen automatically. It will require that these interventions be implemented consistently and equitably across all population groups. In addition, because these policies make it less convenient and more costly to smoke while motivating smokers to quit, a case can be made that they should be accompanied by readily accessible cessation assistance for those smokers who want help quitting, especially in the case of low-income smokers with limited access to cessation services. One way to do this is to dedicate a portion of the funding that states received from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement or from tobacco excise taxes to comprehensive state tobacco control programs, including cessation services. These services can be made available and promoted to low-income residents and other specific population groups with especially high prevalence of tobacco use.

While equitable implementation of tobacco control policies can play a part in achieving equity and eliminating tobacco-related disparities, additional efforts will be necessary. As with tobacco control resources, resources in general have not been distributed equitably in the United States. This has been demonstrated by the socioeconomic construct of the “Two Americas.” The first America is a healthy and socioeconomically advantaged population whereas the second America is an unhealthy, impoverished, and socioeconomically disadvantaged population.34 Thus, it is well-established that individuals with low SES have worse health across many indicators of SES and many measures of health.35 Therefore, in order to achieve equitable health outcomes, people with low SES will need more efforts and resources focused directly to their communities. This is particularly true for certain populations such as Blacks and American Indians/ Alaska Natives that have the highest levels of low SES in this country and suffer disproportionately from tobacco-related disease and death compared to other groups.4

Finally, because there is a complex interplay of factors that determines health behaviors and outcomes, the Healthy People 2020 SDH approach calls for moving beyond controlling diseases to addressing the factors of their root causes. Because addressing some of these root causes may not be feasible within the public health domain, collaborations between public health and other sectors that have primary responsibilities for education, transportation, community design, food and agriculture, and housing and social services will be required.6

Acknowledgments

This paper was prepared with technical assistance from S. Moreland-Russell, PhD, MPH, Center for Tobacco Policy Research.

Funding

None declared.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ten great public health achievements—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011;60:619–623. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6019a5.htm. Accessed December 15, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Current cigarette smoking prevalence among working adults—United States, 2004–2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1305–1309. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6038a2.htm. Accessed December 15, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cigarette smoking—United States, 2006–2008 and 2009–2010. MMWR. 2013;62:81–84. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6203a14.htm. Accessed December 15, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services . Office of the Surgeon General. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups— African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 1998. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/1998/\. Accessed December 15, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. http://whqlibdoc. who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh HK, Piotrowski JJ, Kumanyika S, Fielding JE. Healthy people: a 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38:551–557. doi: 10.1177/1090198111428646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skeer M, George S, Hamilton WL, Cheng DM, Siegel M. Town-level characteristics and smoking policy adoption in Massachusetts: are local restaurant smoking regulations fostering disparities in health protection? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:286–292. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.286. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1448245/pdf/0940286.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arheart KL, Lee DJ, Dietz NA, et al. Declining trends in serum cotinine levels in U.S. worker groups: the power of policy. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:7–63. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318158a486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shopland DR, Anderson CM, Burns DM, Gerlach KK. Disparities in smoke-free workplace policies among food service workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:347–356. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000121129.78510.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Disparities in secondhand smoke exposure—United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. MMWR. 2008;57:744–747. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5727a3.htm. Accessed December 15, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: nonsmokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR. 2010;59:1141–1146. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5935a4.htm. Accessed December 15, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services . Office of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2006/. Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell K, Salmon A, Bowers M, Bell J, McCullough L. Smoking, stigma and tobacco ‘denormalization’: further reflections on the use of stigma as a public health tool. A commentary on Social Science and Medicine’s Stigma, Prejudice, Discrimination and Health Special Issue (67: 3) Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:795–799. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014; Atlanta, GA: 2014. http:// www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/pdfs/2014/comprehensive.pdf?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=best-practices-for-comprehensive-tobacco-control-programs-2014-pdf. Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng K-W, Okechukwu CA, McMillen R, Glantz SA. Association between clean indoor air laws and voluntary smokefree rules in homes and cars. Tob Control. 2013;0:1–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinno A, Glantz S. Tobacco control policies are egalitarian: a vulnerabilities perspective on clean indoor air laws, cigarette prices, and tobacco use disparities. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1439–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baggett TP, Tobey ML, Rigotti NA. Tobacco use among homeless people– addressing the neglected addiction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:201–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1301935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guydish J, Tajima B, Kulaga A, et al. The New York policy on smoking in addiction treatment: findings after 1 year. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e17–e25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pizacani BA, Maher JE, Rohde K, Drach L, Stark MJ. Implementation of a smoke-free policy in subsidized multiunit housing: effects on smoking cessation and secondhand smoke exposure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:1027–1034. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute of Medicine . Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2007. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2007/Ending-the-Tobacco-Problem-A-Blueprint-for-the-Nation.aspx. Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbeau EM, Wolin KY, Naumova EN, Balbach E. Tobacco advertising in communities: associations with race and class. Prev Med. 2005;40:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Office of the Surgeon General. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2012/. Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyland A, Travers MJ, Cummings KM, Bauer J, Alford T. Tobacco outlet density and demographics in Erie County, New York. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1075–1076. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1075. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1075. Accessed December 15, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laws MB, Whitman J, Bowser DM, Krech L. Tobacco availability and point of sale marketing in demographically contrasting districts of Massachusetts. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 2):ii71–ii73. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_2.ii71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Cancer Institute . The Role of Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute, NIH Pub. No. 07-6242; 2008; Bethesda, MD: http://cancer-control.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/19/m19_complete.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niederdeppe J, Kuang X, Crock B, Skelton A. Media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations: what do we know, what do we need to learn, and what should we do now? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1343–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durkin SJ, Biener L, Wakefield MA. Effects of different types of antismoking ads on reducing disparities in smoking cessation among socioeconomic subgroups. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2217–2223. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker J, Davis KC, Wagner L. Socioeconomic variation in recall and perceived effectiveness of campaign advertisements to promote smoking cessation. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:773–780. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siapush M, McNeill A, Hammond D, Fong GT. Socioeconomic and country variations in knowledge of health risks of tobacco smoking and toxic constituents of smoke: results from the 2002 International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl III):III65–70. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francis JA, Abramsohn EM, Park H-Y. Policy-driven tobacco control. Tob Control. 2010;19(suppl 1):i16–i20. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.030718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quill BE, DesVignes-Kendrick M. Reconsidering health disparities. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:505–514. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and health: context or composition? City Community. 2008;7:163–179. [Google Scholar]