Abstract

Understanding how left–right (LR) asymmetry is generated in vertebrate embryos is an important problem in developmental biology. In humans, a failure to align the left and right sides of cardiovascular and/or gastrointestinal systems often results in birth defects. Evidence from patients and animal models has implicated cilia in the process of left–right patterning. Here, we review the proposed functions for cilia in establishing LR asymmetry, which include creating transient leftward fluid flows in an embryonic ‘left–right organizer’. These flows direct asymmetric activation of a conserved Nodal (TGFβ) signalling pathway that guides asymmetric morphogenesis of developing organs. We discuss the leading hypotheses for how cilia-generated asymmetric fluid flows are translated into asymmetric molecular signals. We also discuss emerging mechanisms that control the subcellular positioning of cilia and the cellular architecture of the left–right organizer, both of which are critical for effective cilia function during left–right patterning. Finally, using mosaic cell-labelling and time-lapse imaging in the zebrafish embryo, we provide new evidence that precursor cells maintain their relative positions as they give rise to the ciliated left–right organizer. This suggests the possibility that these cells acquire left–right positional information prior to the appearance of cilia.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Provocative questions in left–right asymmetry’.

Keywords: left–right asymmetry, birth defects, motile cilia, mechanosensory cilia, fluid flow dynamics

1. Introduction

Left–right (LR) asymmetry, or laterality, is a conserved feature of the internal vertebrate body plan. During vertebrate embryogenesis, the primitive heart and gut tubes undergo asymmetric looping to give rise to distinct left and right sides and positions of internal organs. For example, the human heart, stomach and spleen are positioned on the left side of the body, whereas the liver lies on the right side. A perfect mirror-image inversion of this arrangement is called situs inversus totalis, but this carries little or no clinical consequence [1]. By contrast, severe birth defects can arise when laterality is perturbed in specific organs. This condition is referred to as heterotaxy syndrome and causes a broad spectrum of congenital malformations of the heart and gastrointestinal tract [2–4]. Studies in animal models have identified several conserved signalling pathways involved in LR patterning of the vertebrate embryo, but how asymmetric signals are initiated and then relayed to developing organs remains poorly understood.

Pioneering work in chick [5] and mouse [6] embryos in the 1990s identified molecular asymmetries that provide LR patterning information in vertebrate embryos. Signalling molecules were first found to be asymmetrically expressed around a transient embryonic organizer structure called the node (or Hensen's node). Expression of Nodal, a secreted TGF-β family ligand, subsequently expands into lateral plate mesoderm exclusively on the left side of the embryo to activate its own expression and its feedback inhibitor Lefty [7] and the homeobox transcription factor Pitx2 [8]. Unlike Nodal, asymmetric expression of Pitx2 persists in the developing heart and gut tubes to control asymmetric organ morphogenesis [9–11]. This asymmetric Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 cassette is highly conserved in vertebrate embryos, and functional studies have demonstrated the importance of this signalling cascade for establishing organ laterality [12,13]. However, the mechanism(s) underlying the unilateral expression of this cascade remains a subject of debate.

Studies of a rare genetic disorder called Kartagener syndrome (KS) first provided an intriguing link between LR patterning and motile cilia. It was discovered that KS, which is characterized by respiratory dysfunction and male infertility, was caused by loss of cilia motility [14,15]. Motile cilia—microtubule-based whip-like projections from cells—beat in airways to drive mucociliary clearance of debris and pathogens; thus, respiratory defects are consistent with loss of cilia movement. Likewise, loss of motility of flagella, which are cilia-related structures that power sperm swimming, explains infertility in KS. Along with mucociliary and sperm problems, approximately 50% of KS patients have situs inversus totalis. This implicates motile cilia in establishing normal LR asymmetry of the body. In addition to situs inversus totalis, heterotaxy has also been found in primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) patients with cilia motility defects [16–18], indicating that loss of cilia motility can result in either reversed or ambiguous LR asymmetry [4]. Indeed, mutations in several genes involved in building ciliary ultrastructure have been identified in patients with laterality defects [19,20].

2. Functions of cilia in left–right patterning

(a). Motile cilia generate asymmetric fluid flows

The use of animal models has been instrumental for uncovering roles for cilia in LR development. A landmark study using knockout mice deficient for a kinesin protein first identified a transient group of monociliated cells in the ventral node of the embryo that are essential for establishing LR asymmetry [21]. Kinesin family motor proteins are involved in microtubule-dependent transport of a variety of cargoes and are required for the assembly of cilia in a process called intraflagellar transport [22]. Mouse knockouts of the kinesin gene Kif3B failed to assemble cilia and developed LR patterning defects [21]. Video microscopy revealed cilia in the ventral node in wild-type embryos beat with a clockwise vortical motion [23] to generate a right-to-left flow of extraembryonic fluid, which was termed ‘nodal flow’ [21]. Importantly, this asymmetric flow occurred just prior to the onset of asymmetric Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 signalling. Mouse Kif3B knockouts lacked node cilia and nodal flow and developed defects in asymmetric Lefty expression and heart laterality. Studies using inversus viscerum (iv) mice with mutations in the left–right dynein (lrd) gene, which encodes the dynein axonemal heavy chain protein Dnah11 that is required for cilia motility, provided an additional link between paralysed node cilia and randomization of LR asymmetry [24–26]. More recently, an unbiased large-scale forward genetic screen identified mutations in 23 cilia-associated genes in laterality mutants [27], corroborating the critical role for cilia in LR patterning. The notion that directional fluid flows control LR patterning was demonstrated by the remarkable observation that Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 asymmetry could be manipulated ex utero by applying artificial flow to mouse embryos in culture [28]. LR asymmetry in wild-type embryos was reversed with left-to-right artificial flows across the node, and laterality defects in iv mutants were rescued by applying normal right-to-left flows. These results support a model in which cilia-driven nodal flow is an essential cue that directs LR asymmetric expression of the Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 cascade (figure 1). Although cilia are not required for LR asymmetry in all vertebrates (which is discussed in detail below), the finding that several vertebrate embryos have transient epithelial structures analogous to the mouse node that harbour motile cilia and asymmetric flows upstream of Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 signalling suggests a conserved function for motile cilia in LR patterning [29]. These ciliated structures include (i) Kupffer's vesicle (KV), an ellipsoid organ in teleost fishes medaka [23] and zebrafish [30,31], (ii) gastrocoel roof plate, a flat triangular to diamond shaped epithelium in frog [32], and (iii) posterior notochordal plate, a convex ridge in rabbit [23]. Owing to the differences in names and locations, these analogous structures will be collectively referred to as the ciliated ‘left–right organizer’ (LRO).

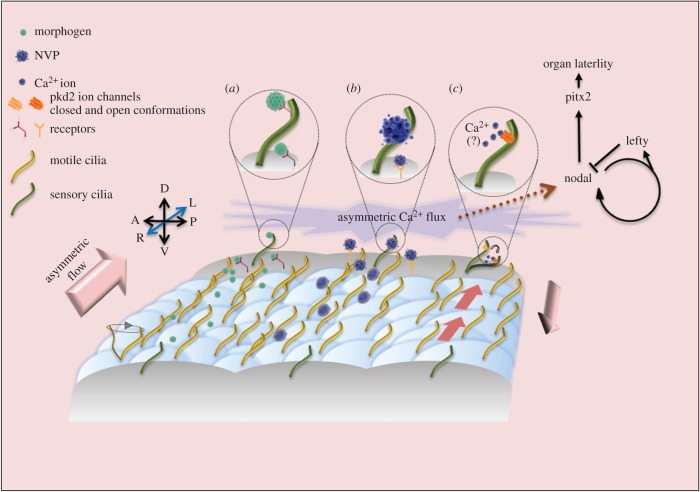

Figure 1.

Functions of cilia in establishing vertebrate LR asymmetry. This schematic represents the transient LRO described in several vertebrate embryos that is comprised of epithelial cells that have either motile (yellow) or non-motile sensory cilia (green). The motile cilia beat with a vortical pattern and are posteriorly tilted to generate strong leftward fluid flows and slower rightward return flows. Leftward flows are essential for activating an asymmetric Ca2+ flux and the Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 signalling cascade that controls LR asymmetry of developing organs. Three hypotheses have been proposed to explain how flows trigger asymmetric signals: (a) the ‘morphogen gradient model’ predicts that flows create a left-to-right concentration gradient of secreted signalling molecule(s) that bind receptors on the left side; (b) ‘nodal vesicular parcels’ (NVPs) that contain signalling molecules have been proposed to be transported to the left by flows; and (c) the ‘two-cilia model’ suggests that flows bend sensory cilia containing the ion channel Pkd2 to activate Ca2+ uptake on the left side. Recent results have challenged the idea of Ca2+-mediated mechanosensory functions for cilia, which is represented by (?). D = dorsal; V = ventral; L = left; R = right.

What do cilia-generated flows look like in LROs? In contrast with multiciliated cells that move mucus through airways in a single direction, monociliated cells in LROs create asymmetric flows in relatively small pools of recirculating extraembryonic fluid. Several innovative approaches have been developed to visualize and quantify these flows. Real-time tracking of fluorescent microbeads applied to the pit-like structure of the mouse node in cultured embryos revealed flows move leftward near the bottom of the ciliated pit and then return to the right near the top of the membrane-covered LRO [23]. Particle image velocimetry (PIV) analysis of flowing microbeads has been effectively used to measure flows in wild-type and mutant mouse embryos in culture and shed light on the relationship between flow strength and LR patterning (discussed more below) [33]. Analyses of microbead movements across the frog-gastrocoel roof plate using a semi-automated methodology called gradient time trails indicated microbeads that originate on the right margin are quickly moved to the left margin at specific developmental stages [32]. Understanding the dynamics of flows inside the fish LRO (KV) has been more challenging due to its more sphere-like shape. Anticlockwise rotational flow patterns have been described in KV by tracking fluorescent microbeads using manual [34] or automated [35] approaches or by tracking laser-induced cellular debris [36]. Observations of flow dynamics indicated strong right-to-left flow in anterior region of the LRO and slower return right to left flow at posterior pole [31,37,38]. More recently, automated analyses using customized ImageJ plugins [39] to track naturally occurring particles or a customized Matlab code [40] to track microbeads have generated ‘heat maps’ that show local flow intensities and confirm strong right-to-left flows in the anterior region. Thus, while imaging flows in living vertebrate embryos has revealed different dynamics in different species, the overarching theme of creating strong right-to-left flows is consistent among LROs (figure 1).

(b). Sensing asymmetric flows

Although solid evidence supports the role for cilia-driven directional fluid flows in establishing LR asymmetry in multiple vertebrates, how these flows are detected and translated into molecular asymmetries (e.g. Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 expression) remains enigmatic. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how flows generate asymmetric signalling (figure 1). The ‘morphogen gradient model’ (figure 1a) proposes that directional flow sets up the left side of the LRO to receive a greater concentration of a secreted molecule(s) that triggers downstream asymmetric signalling. Indeed, fluorescent proteins introduced into the mouse node formed a left-to-right gradient [23], but endogenous secreted molecules/morphogens that direct Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 expression have not been identified. Another model involves membrane-covered ‘nodal vesicular parcels’ (NVPs) (figure 1b) that contain signalling molecules that get swept to the left side of the LRO by cilia-driven flows [41]. Time-lapse imaging of cultured mouse embryos was used to track particles (NVPs) released into the node and then fragmented at the left wall. It was found that sonic hedgehog and retinoic acid were ensheathed in the NVPs and then released into the nodal flow in a fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-signalling-dependent manner. This is an attractive model that connects asymmetric flow with asymmetric delivery of signalling molecules, but a lack of additional studies beyond the initial observations of NVPs has left the regulatory details unclear.

As an alternative to the idea that asymmetric flows physically move signalling molecules, it was proposed that flow acts as a mechanical force to bend mechanosensory cilia on the left side of the embryo to activate signalling [42,43]. This ‘two-cilia model’ (figure 1c) posits that in addition to motile cilia that generate flow, there is a second population of non-motile sensory cilia that detect this flow. The initial evidence backing this model came from the discovery that mutations in the calcium ion (Ca2+) permeable channel protein Pkd2—which localizes to sensory cilia—disrupted LR patterning [44]. Subsequently, fluorescent Ca2+ indicator dyes and genetically encoded fluorescent Ca2+ reporters identified transient Ca2+ signalling on the left side of the LRO in mouse [42] and zebrafish [45] embryos just before the onset of asymmetric Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 signalling. Loss of cilia-driven asymmetric flow [42] or Pkd2 ion channel expression [46], led to symmetric Ca2+ activity around the LRO and LR patterning defects, suggesting asymmetric Ca2+ flux is a key response downstream of flow. Based on observations that bending mechanosensory cilia on kidney cells allows Ca2+ to flow into the cell [47], it was hypothesized that stretch-sensitive Pkd2 channels in sensory cilia would open in response the mechanical stimulus of asymmetric flow on the left side of the LRO to establish left-sided Ca2+ flux. Indeed, Pkd2 protein localizes to LRO cilia in mouse [42], frog [32] and fish [48]. In the mouse LRO, Pkd2 was found in both motile cilia in the pit-like structure of the node and immotile cilia that are largely found in the surrounding crown cells [42,46]. Importantly, a mutant version of the Pkd2 protein that retained channel activity but could not localize to cilia failed to rescue asymmetric gene expression in Pkd2 mutant embryos [46]. Furthermore, when Pkd2 expression was reintroduced specifically in the crown cells of Pkd2 knockout mice, it rescued asymmetry of Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 expression [46]. These results indicated the presence of Pkd2 in the cilium of cells surrounding flow-generating cells is important for LR signalling (figure 1c). Live imaging of fluorescent Ca2+ reporters in the zebrafish LRO identified Ca2+ flashes in cilia, called intraciliary calcium oscillations (ICOs), that preceded cytoplasmic Ca2+ signals in a Pkd2-dependent fashion [49]. This provided additional evidence that Pkd2 channels were opening in cilia to allow Ca2+ to enter the cell body and initiate Ca2+ flux in LRO cells.

Although the two-cilia model has garnered much support, recent studies have challenged the idea that cilia function as mechnosensors via Ca2+ signalling. First, work in cultured human cells indicated increased Ca2+ in primary cilia did not have a significant impact on cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels and did not stimulate Ca2+ release [50]. More recently, high-speed imaging of Ca2+ dynamics in transgenic mice expressing a Ca2+ indicator that localizes specifically to cilia showed that externally applied flows (at physiological levels or higher) failed to elicit Ca2+ response in primary cilia in diverse tissues [51]. Studies of the node in these transgenic mice revealed that physiological flow velocities barely deflected nodal crown cilia and did not evoke Ca2+ influx inside these cilia. It was suggested that previously observed Ca2+ signals within the cilium arise from Ca2+ diffusion from the cell body or entry due to damage to the cilia caused by external shear stress. Taken together these observations suggest that if cilia are mechanosensory, the mechanism does not involve Ca2+ entry through the cilium. Genetically encoded calcium sensors do have limitations [52], but these findings ask for a re-evaluation of the role of Pkd channels in LR patterning and a search for alternative ions and/or receptors that may be involved in sensing LRO flows.

Whether flows move morphogens or provide a mechanical stimulus remains an open and intriguing question. The mouse LRO contains between 200 and 300 motile cilia that produce strong leftward flows, and it was predicted that most of these cilia, if not all, were required to work in concert to establish robust flows and LR asymmetry. When movements of these cilia were retarded using a viscous material (methyl cellulose) in cultured mouse embryos, it was observed that weak and transient local flows were sufficient to initiate LR asymmetric gene expression [33]. This finding was confirmed in mouse cilia motility mutants Rfx3−/− or Dpcd−/− in which complete loss of flow disrupted LR asymmetry, but weak flows created by as few as two motile cilia were sufficient to generate normal LR signals [33]. Analyses and mathematical simulations of flow dynamics in the zebrafish LRO also predict only a subset of beating cilia (30 out of normal number of 50–60 motile cilia) are necessary to generate LR asymmetry [39], which correlates with an observed minimum size threshold for zebrafish LRO function [53]. Thus, looking forward, it will be important to determine whether weak localized flows can effectively transport morphogens or NVPs across the LRO, or activate mechanosensory mechanisms to regulate downstream asymmetric signalling events.

3. Cilia position matters

(a). Polarization of cilia

As hinted at above, the size and cellular architecture of LROs are quite different in different vertebrate species (see reviews: [54–56]). Despite these differences, one would predict that the arrangement and positioning of cilia in the LRO must be tightly regulated in order for these cilia to work in a coordinated fashion to generate effective fluid flows and LR signals. A long-standing question has been how clockwise vortical motion of LRO cilia generates a dominant unidirectional flow. Theoretical simulations of flow dynamics first suggested that motile monocilia are tilted posteriorly in the LRO [57]. Indeed, studies in mouse [23,58], rabbit [23], frog [32] and zebrafish [31,59] have identified posterior tilting of LRO cilia. High-speed imaging of cilia in the mouse LRO showed that the trajectory of cilia tips is shifted towards the posterior when compared with cilia roots [23]. This tilt allows a rotating cilium to make a leftward swing away from the cell surface and a rightward swing towards the cell surface. As the cell surface retards the movement of fluid by shear resistance, the leftward swing results in a higher degree of flow than the rightward swing, resulting in a net leftward flow [23,60].

This leads to the question of how cilia become tilted in LRO cells. Studies in mouse [23], rabbit [61] and frog [32] indicate cilia initially protrude from the centre of the apical surface of each cell, but then become posteriorly localized at stages that coincide with the onset of leftward flows. Such positioning of LRO cilia appears to be mediated by movement of the cilium base, or basal body, to the posterior pole of the cell [23]. Genetic studies indicate planar cell polarity (PCP) proteins are involved in the posterior migration of basal bodies in LRO cells. PCP refers to polarization of a field of cells in the plane of an epithelium first described in Drosophila [62]. Compound loss-of-function of the PCP genes Disheveled (triple knockout of Dvl1, Dvl2, Dvl3) or Van gogh like (double knockout of Vangl1 and Vangl2) in mouse embryos disrupted posterior positioning of LRO basal bodies and cilia [63,64]. This failure to tilt the cilia resulted in aberrant flows and LR defects. Protein localization studies revealed that the PCP proteins Vangl1 and Prickle2 accumulated on the anterior side of mouse LRO cells, whereas Dvl was found on the posterior [63,65]. These asymmetric localizations indicate LRO cells are polarized along the anteroposterior axis, but the mechanisms setting up this polarization are not understood [66,67]. Loss of Vangl2 in frog [65] and zebrafish [59] also disrupted LRO cilia posterior polarization, fluid flows and LR patterning. Collectively, these results indicate PCP-mediated posterior polarization of cilia is a conserved and essential mechanism for generating unidirectional flows and LR asymmetry.

(b). Positioning of ciliated cells

In addition to polarization and posterior tilt of LRO cilia, the arrangement of cells in the LRO plays important roles in generating fluid flows and LR signals. Emerging evidence points to distinct subpopulations of cells in LROs that must be properly positioned to produce and/or respond to flows. In mouse and frog LROs, cells with small apical surfaces and motile cilia are flanked on the left and right sides by much larger cells that express distinct molecular markers and show a mixed population of motile and immotile cilia [32,42,46]. Disruption of this arrangement in mouse Noto−/− [68] or Zic3−/− [69,70] mutants—such that the small cells are mixed with the larger cells—altered LR patterning. Further, Notch signalling regulated by the glycosylation factor Galnt11 determines the relative distribution of motile and non-motile ciliated cells in the frog LRO [71]. In zebrafish, the cellular architecture of KV is asymmetric along the anteroposterior and dorsoventral axes. KV cells in the dorsoanterior region develop an elongated columnar morphology with small apical surfaces—which allows tight packing of these cells—whereas ventroposterior cells adopt a cuboidal morphology with large apical surfaces [37,38]. This process, referred to as ‘KV remodelling’ [72], places more motile cilia in the dorsoanterior region to drive strong leftward flow across the anterior pole as described above. As observed in mouse and frog embryos, disrupting the arrangement of ciliated cells in the zebrafish LRO leads to flow and LR patterning defects [38,72,73].

Recent studies have identified regulators of the actomyosin cytoskeleton and components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) as mediators of LRO cell positioning. The Rho kinase protein Rock2, which operates downstream of Rho GTPase signals to modify the actomyosin cytoskeleton, was identified in a copy number variant screen in patients with heterotaxy syndrome [74]. Rock2 proteins are expressed in frog and zebrafish LROs, and loss-of-function studies confirmed their involvement in LR patterning [38,74]. In zebrafish, depletion of the Rock protein Rock2b or chemical inhibition of its target non-muscle myosin II did not affect cilia motility, but prevented regional cell shape changes during KV remodelling that position more cilia in the dorsoanterior region of the LRO [38,72]. This eliminated leftward flow and altered LR signalling. Regulators of actomyosin activity are also involved in establishing the cellular architecture of the mouse LRO. Loss of the Rho family GTPase Rac1 or the FERM domain protein Lulu/Epb4.1l5 disrupted the movements of ciliated columnar cells with small apical surfaces that must displace larger endoderm cells to reach the ventral surface of the embryo [75]. Mouse embryos with mutations in fibronectin and/or integrin have revealed roles for ECM in establishing normal node morphology and geometry [76,77]. Analyses of endogenous as well as ectopically induced KV in zebrafish embryos have also identified important roles for ECM proteins in positioning ciliated cells [73]. Interfering with laminin or fibronectin, which accumulate at the axial–paraxial boundary adjacent to densely packed dorsalanterior cells, inhibited KV remodelling that is critical for generating leftward flows [73]. Taken together, these observations suggest precise organization of cells generates an architectural asymmetry within the LRO that is critical for its function and regulation of LR asymmetry.

(c). Laterality cues for cilia?

While it is clear that tight regulation of the ciliated cells in LROs is important for establishing LR signalling, it is less clear whether cilia-generated flows provide the initial break of symmetry. First, cilia are not universally required to establish LR asymmetry in all vertebrates. In the chicken embryo, Hensen's node is site of the first asymmetric gene expression, but this structure is thought to lack motile cilia. Chicken Talpid3 mutants with cilia defects develop normal LR asymmetry [78–80], indicating a cilia-independent mechanism is used for breaking symmetry. Indeed, cell-tracking experiments revealed that asymmetric cell movements around Hensen's node set up asymmetric signalling in the chicken embryo [81]. Intriguingly, the node in the pig embryo also lacks cilia [81] and, unlike the mouse ventral node that is exposed to extraembryonic fluid, pig node cells are covered by a layer of cells referred to as subchordal mesoderm [82]. The node of the cow embryo is also enclosed in subchordal mesoderm [82], suggesting multiple vertebrates use cilia-independent mechanisms to establish LR asymmetry. Second, several events that impact LR asymmetry described in the frog embryo occur prior to the appearance and function of cilia in the LRO [83,84]. These include signalling between ectoderm and migrating mesoderm cells mediated by the heparan sulfate proteoglycan Syndecan 2 during gastrulation stages [85,86] and ion gradients established by the H+ /K+-ATPase [87] and vacuolar-type H+-ATPase [88] proton pumps that could drive asymmetric localization of determinants, such as serotonin [89], at early cleavage stages. It has been proposed [90] that intrinsic chirality of the cytoskeleton is used to asymmetrically transport molecules (e.g. ion pumps) [91] or mediate the LR distribution of differentially imprinted chromatids [92] to break symmetry in the early embryo. It is possible that early developmental events generate LR positional information that can be used to guide ciliated cells as they develop into a functional LRO or to completely bypass the requirement for cilia [93,94].

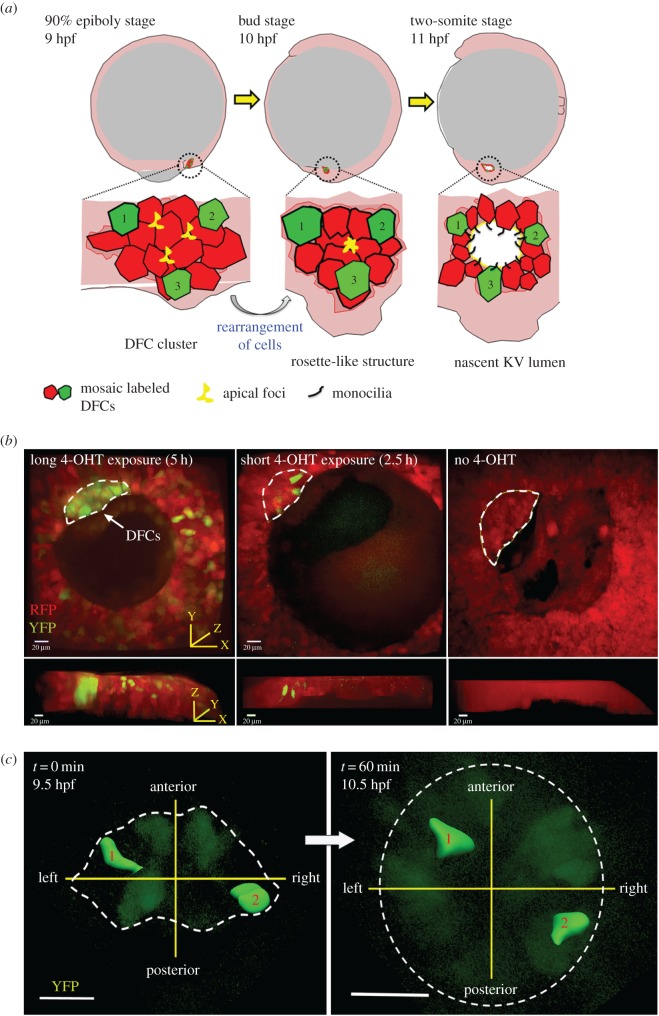

Several connections have been made between molecules involved in early LR events and the development of the LRO: Syndecan 2 [95] and the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase [88,96,97] are involved in the development of normal LRO morphogenesis and cilia formation in zebrafish, and H+/K+-ATPase activity [98] and serotonin [99] are needed for Wnt signalling pathways that control LRO development and ciliogenesis in frog embryos. One outstanding question is whether precursor cells receive laterality cues prior to forming the LRO. As discussed above, the location of different types of cells within the LRO is critical for their functions; however, it is not known whether these subpopulations differentiate and organize at the time of LRO morphogenesis or bring with them fates that were determined at earlier stages of development. To begin to address this question, we are taking advantage of the zebrafish embryo to investigate the behaviours of precursor cells that give rise to the LRO. Unlike other vertebrates, fate-mapping studies [100,101] have identified all of the precursors—called dorsal forerunner cells (DFCs)—that form the zebrafish KV/LRO (figure 2). Transgenic embryos that express GFP in the DFCs using a sox17 promoter [102] have been widely used to track the development of these cells. During gastrulation stages, DFCs migrate together toward the vegetal pole of the embryo and then compact into a tight a cluster. Connections with overlying cells provide multiple foci of apical membrane and junction proteins [103]. DFCs then undergo rearrangements that bring the foci into close proximity to form a rosette-like structure that gives rise to the nascent lumen where cilia begin to elongate (figure 2a). Formation of rosette-like structures has also been described during early morphogenesis of the mouse node/LRO [75]. However, it is not known whether precursor cells randomly incorporate into these rosettes or take up pre-determined positions.

Figure 2.

Tracking precursor cells of the zebrafish left–right organizer Kupffer's vesicle. (a) Schematic of the development of dorsal forerunner cells (DFCs) into Kupffer's vesicle (KV) in the zebrafish embryo. A cluster of DFCs at the 90% epiboly stage or 9 h post-fertilization (hpf) rearranges to form a rosette-like structure with a central point of apical membrane proteins at the bud stage (10 hpf). These cells epithelialize, form cilia and begin to expand the fluid-filled lumen by the two-somite stage (11 hpf). Red and green cells represent mosaic labelling of DFCs using a loxP-Cre approach (see electronic supplementary material methods). (b) Mosaic labelling of DFCs in Tg(ubi:Zebrabow);Tg(sox17:CreERT2) double transgenic embryos imaged at the 80–90% epiboly stages. Long treatments with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) from dome stage to 90% epiboly stage (approx. 5 h) resulted in widespread Cre activity in DFCs that converted most or all of the cells from expressing default red fluorescent protein (RFP) to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). Short 4-OHT treatments from the dome stage to 60% epiboly stage (approx. 2.5 h) labelled only a few DFCs with YFP expression. Embryos not treated with 4-OHT had no YFP+ cells. Both vegetal and side views are shown for each embryo. Scale bars = 20 µm. (c) Time-lapse imaging was used to analyse individual YFP+ DFCs during development. Three-dimensional reconstructions of YFP+ DFCs that did not divide were tracked for 60 min. starting approximately 9.5 hpf. In this representative analysis, labelled cells #1 and #2 maintained their relative positions during the DFC to KV transition. Scale bars = 50 µm. Dotted lines are approximate boundaries of DFC clusters.

To investigate the behaviour of cells during this process, we developed a Cre-loxP–based mosaic cell-labelling method (see electronic supplementary material methods) to monitor individual DFCs in living zebrafish embryos (figure 2b). Time-lapse microscopy was used to track labelled DFCs during the process of clustering, rosette formation and lumen expansion. Interestingly, this analysis revealed little or no mixing of cells during this process: a cell located in a specific quadrant of the DFC cluster retained that position during formation of KV (electronic supplementary material, Movie 1). For example, a cell that originated in the left-anterior quadrant of the precursor pool became a ciliated cell in the left-anterior quadrant of the LRO (figure 2c). These observations suggest precursor cells are not stochastically arranged in the LRO as it forms, but rather these cells acquire positional information—and potentially specific cell fates—at earlier stages of development. It will be interesting to test this hypothesis in future studies and investigate factors that may provide laterality cues for cilia during development.

4. Conclusion

Understanding how, when and where LR asymmetry is established in vertebrate embryos remains a fascinating problem that holds significant biomedical relevance. The discovery of cilia motility defects in patients with LR malformations has provided insight into how the asymmetric body plan is set up during embryogenesis, and work using animal models has identified roles for cilia in generating left-sided Nodal-Lefty-Pitx2 asymmetry. But, exactly how cilia generate LR asymmetry is not yet clear. One important unanswered question is how weak fluid flows produced by only a few motile cilia are detected and translated into molecular signals. It remains to be determined whether mechanosensitive cilia, morphogen gradients or vesicular particles—which are not mutually exclusive mechanisms—are involved in sensing flows. New studies are also needed to further clarify how functions of cilia are influenced by the cellular topography of the LRO. In addition, it will be important to determine whether precursors of these ciliated cells are asymmetrically patterned and/or specified into distinct subpopulations prior to the appearance of the LRO. Answers to these questions will be critical for advancing our understanding of how cilia generate LR asymmetry in the vertebrate body plan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Amack laboratory for helpful discussions and Andrew Jacob for assistance with mosaic labelling of zebrafish embryos. We also thank Sharleen Buel for outstanding technical assistance and animal care.

Ethics

All zebrafish experiments were conducted with approval by SUNY Upstate Medical University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Data accessibility

Methods and data supporting figure 2 have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

Experiments were designed by J.D.A. and A.D. A.D. performed these experiments. A.D and J.D.A. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL095690) and National Institute of General Medical Science (R01GM117598).

References

- 1.Peeters H, Devriendt K. 2006. Human laterality disorders. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 49, 349–362. ( 10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.12.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutherland MJ, Ware SM. 2009. Disorders of left-right asymmetry: heterotaxy and situs inversus. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 151C, 307–317. ( 10.1002/ajmg.c.30228) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsdell AF. 2005. Left-right asymmetry and congenital cardiac defects: getting to the heart of the matter in vertebrate left-right axis determination. Dev. Biol. 288, 1–20. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brueckner M. 2007. Heterotaxia, congenital heart disease, and primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation 115, 2793–2795. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699256) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin M, Johnson RL, Stern CD, Kuehn M, Tabin C. 1995. A molecular pathway determining left-right asymmetry in chick embryogenesis. Cell 82, 803–814. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90477-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe LA, Supp DM, Sampath K, Yokoyama T, Wright CV, Potter SS, Overbeek P, Kuehn MR. 1996. Conserved left-right asymmetry of nodal expression and alterations in murine situs inversus. Nature 381, 158–161. ( 10.1038/381158a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meno C, Saijoh Y, Fujii H, Ikeda M, Yokoyama T, Yokoyama M, Toyoda Y, Hamada H. 1996. Left-right asymmetric expression of the TGFbeta-family member lefty in mouse embryos. Nature 381, 151–155. ( 10.1038/381151a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshioka H, et al. 1998. Pitx2, a bicoid-type homeobox gene, is involved in a lefty-signaling pathway in determination of left-right asymmetry. Cell 94, 299–305. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81473-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurpios NA, Ibanes M, Davis NM, Lui W, Katz T, Martin JF, Belmonte JCI, Tabin CJ et al. 2008. The direction of gut looping is established by changes in the extracellular matrix and in cell:cell adhesion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8499–8506. ( 10.1073/pnas.0803578105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis NM, Kurpios NA, Sun X, Gros J, Martin JF, Tabin CJ. 2008. The chirality of gut rotation derives from left-right asymmetric changes in the architecture of the dorsal mesentery. Dev. Cell. 15, 134–145. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welsh IC, Thomsen M, Gludish DW, Alfonso-Parra C, Bai Y, Martin JF, Kurpios NA. 2013. Integration of left-right Pitx2 transcription and Wnt signaling drives asymmetric gut morphogenesis via Daam2. Dev. Cell. 26, 629–644. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamada H, Meno C, Watanabe D, Saijoh Y. 2002. Establishment of vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 103–113. ( 10.1038/nrg732) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juan H, Hamada H. 2001. Roles of nodal-lefty regulatory loops in embryonic patterning of vertebrates. Genes Cells 6, 923–930. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00481.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afzelius BA. 1976. A human syndrome caused by immotile cilia. Science 193, 317–319. ( 10.1126/science.1084576) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen H, Mygind N. 1976. Absence of axonemal arms in nasal mucosa cilia in Kartagener's syndrome. Nature 262, 494–495. ( 10.1038/262494a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy MP, et al. 2007. Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation 115, 2814–2821. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapiro AJ, et al. 2014. Laterality defects other than situs inversus totalis in primary ciliary dyskinesia: insights into situs ambiguus and heterotaxy. Chest 146, 1176–1186. ( 10.1378/chest.13-1704) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, et al. 2016. DNAH6 and its interactions with PCD genes in heterotaxy and primary ciliary dyskinesia. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005821 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005821) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knowles MR, Daniels LA, Davis SD, Zariwala MA, Leigh MW. 2013. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. Recent advances in diagnostics, genetics, and characterization of clinical disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 913–922. ( 10.1164/rccm.201301-0059CI) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Praveen K, Davis EE, Katsanis N. 2015. Unique among ciliopathies: primary ciliary dyskinesia, a motile cilia disorder. F1000Prime Rep. 7, 36 ( 10.12703/P7-36) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Takeda S, Harada A, Kanai Y, Kido M, Hirokawa N et al. 1998. Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell 95, 829–837. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81705-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholey JM. 2008. Intraflagellar transport motors in cilia: moving along the cell's antenna. J. Cell Biol. 180, 23–29. ( 10.1083/jcb.200709133) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okada Y, Takeda S, Tanaka Y, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Hirokawa N. 2005. Mechanism of nodal flow: a conserved symmetry breaking event in left-right axis determination. Cell 121, 633–644. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada Y, Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, Saijoh Y, Hamada H, Hirokawa N. 1999. Abnormal nodal flow precedes situs inversus in iv and inv mice. Mol. Cell. 4, 459–468. ( 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80197-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Supp DM, Witte DP, Potter SS, Brueckner M. 1997. Mutation of an axonemal dynein affects left-right asymmetry in inversus viscerum mice. Nature 389, 963–966. ( 10.1038/40140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Supp DM, et al. 1999. Targeted deletion of the ATP binding domain of left-right dynein confirms its role in specifying development of left-right asymmetries. Development 126, 5495–5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, et al. 2015. Global genetic analysis in mice unveils central role for cilia in congenital heart disease. Nature 521, 520–524. ( 10.1038/nature14269) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nonaka S, Shiratori H, Saijoh Y, Hamada H. 2002. Determination of left-right patterning of the mouse embryo by artificial nodal flow. Nature 418, 96–99. ( 10.1038/nature00849) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blum M, Feistel K, Thumberger T, Schweickert A. 2014. The evolution and conservation of left-right patterning mechanisms. Development 141, 1603–1613. ( 10.1242/dev.100560) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Essner JJ, Amack JD, Nyholm MK, Harris EB, Yost HJ. 2005. Kupffer's vesicle is a ciliated organ of asymmetry in the zebrafish embryo that initiates left-right development of the brain, heart and gut. Development 132, 1247–1260. ( 10.1242/dev.01663) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer-Zucker AG, Olale F, Haycraft CJ, Yoder BK, Schier AF, Drummond IA. 2005. Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer's vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development 132, 1907–1921. ( 10.1242/dev.01772) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweickert A, Weber T, Beyer T, Vick P, Bogusch S, Feistel K, Blum M. 2007. Cilia-driven leftward flow determines laterality in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 17, 60–66. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shinohara K, et al. 2012. Two rotating cilia in the node cavity are sufficient to break left-right symmetry in the mouse embryo. Nat. Commun. 3, 622 ( 10.1038/ncomms1624) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang G, Yost HJ, Amack JD. 2013. Analysis of gene function and visualization of cilia-generated fluid flow in Kupffer's vesicle. J. Vis. Exp. 73 ( 10.3791/50038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hochgreb-Hägele T, Yin C, Koo DE, Bronner ME, Stainier DY. 2013. Laminin beta1a controls distinct steps during the establishment of digestive organ laterality. Development 140, 2734–2745. ( 10.1242/dev.097618) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Supatto W, Fraser SE, Vermot J. 2008. An all-optical approach for probing microscopic flows in living embryos. Biophys. J. 95, L29–L31. ( 10.1529/biophysj.108.137786) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okabe N, Xu B, Burdine RD. 2008. Fluid dynamics in zebrafish Kupffer's vesicle. Dev. Dyn. 237, 3602–3612. ( 10.1002/dvdy.21730) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G, Cadwallader AB, Jang DS, Tsang M, Yost HJ, Amack JD. 2011. The Rho kinase Rock2b establishes anteroposterior asymmetry of the ciliated Kupffer's vesicle in zebrafish. Development 138, 45–54. ( 10.1242/dev.052985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampaio P, et al. 2014. Left-right organizer flow dynamics: how much cilia activity reliably yields laterality? Dev. Cell 29, 716–728. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fox C, Manning ML, Amack JD. 2015. Quantitative description of fluid flows produced by left-right cilia in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol. 127, 175–187. ( 10.1016/bs.mcb.2014.12.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. 2005. FGF-induced vesicular release of Sonic hedgehog and retinoic acid in leftward nodal flow is critical for left-right determination. Nature 435, 172–177. ( 10.1038/nature03494) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGrath J, Somlo S, Makova S, Tian X, Brueckner M. 2003. Two populations of node monocilia initiate left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Cell 114, 61–73. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00511-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabin CJ, Vogan KJ. 2003. A two-cilia model for vertebrate left-right axis specification. Genes Dev. 17, 1–6. ( 10.1101/gad.1053803) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pennekamp P, Karcher C, Fischer A, Schweickert A, Skryabin B, Horst J, Blum M, Dworniczak B. 2002. The ion channel polycystin-2 is required for left-right axis determination in mice. Curr. Biol. 12, 938–943. ( 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00869-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarmah B, Latimer AJ, Appel B, Wente SR. 2005. Inositol polyphosphates regulate zebrafish left-right asymmetry. Dev. Cell 9, 133–145. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshiba S, et al. 2012. Cilia at the node of mouse embryos sense fluid flow for left-right determination via Pkd2. Science 338, 226–231. ( 10.1126/science.1222538) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nauli SM, et al. 2003. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat. Genet. 33, 129–137. ( 10.1038/ng1076) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamura K, Kobayashi D, Uehara Y, Koshida S, Iijima N, Kudo A, Yokoyama T, Takeda H. 2011. Pkd1l1 complexes with Pkd2 on motile cilia and functions to establish the left-right axis. Development 138, 1121–1129. ( 10.1242/dev.058271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan S, Zhao L, Brueckner M, Sun Z. 2015. Intraciliary calcium oscillations initiate vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 25, 556–567. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.051) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delling M, DeCaen PG, Doerner JF, Febvay S, Clapham DE. 2013. Primary cilia are specialized calcium signalling organelles. Nature 504, 311–314. ( 10.1038/nature12833) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delling M, Indzhykulian AA, Liu X, Li Y, Xie T, Corey DP, Clapham DE. 2016. Primary cilia are not calcium-responsive mechanosensors. Nature 531, 656–660. ( 10.1038/nature17426) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitaker M. 2010. Genetically encoded probes for measurement of intracellular calcium. Methods Cell Biol. 99, 153–182. ( 10.1016/B978-0-12-374841-6.00006-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gokey JJ, Ji Y, Tay HG, Litts B, Amack JD. 2016. Kupffer's vesicle size threshold for robust left-right patterning of the zebrafish embryo. Dev. Dyn. 245, 22–33. ( 10.1002/dvdy.24355) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amack JD. 2014. Salient features of the ciliated organ of asymmetry. Bioarchitecture 4, 6–15. ( 10.4161/bioa.28014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blum M, Beyer T, Weber T, Vick P, Andre P, Bitzer E, Schweickert A. 2009. Xenopus, an ideal model system to study vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Dev. Dyn. 238, 1215–1225. ( 10.1002/dvdy.21855) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JD, Anderson KV. 2008. Morphogenesis of the node and notochord: the cellular basis for the establishment and maintenance of left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Dev. Dyn. 237, 3464–3476. ( 10.1002/dvdy.21598) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cartwright JHE, Piro O, Tuval I.2004. Fluid-dynamical basis of the embryonic development of left-right asymmetry in vertebrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7234–7239. ( ) [DOI]

- 58.Nonaka S, Yoshiba S, Watanabe D, Ikeuchi S, Goto T, Marshall WF, Hamada H, Stemple D. 2005. De novo formation of left-right asymmetry by posterior tilt of nodal cilia. PLoS Biol. 3, e268 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030268) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borovina A, Superina S, Voskas D, Ciruna B. 2010. Vangl2 directs the posterior tilting and asymmetric localization of motile primary cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 407–412. ( 10.1038/ncb2042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cartwright JHE, Piro N, Piro O, Tuval I. 2008. Fluid dynamics of establishing left-right patterning in development. Birth Defects Res. Part C, Embryo Today: Rev. 84, 95–101. ( 10.1002/bdrc.20127) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feistel K, Blum M. 2006. Three types of cilia including a novel 9+4 axoneme on the notochordal plate of the rabbit embryo. Dev. Dyn. 235, 3348–3358. ( 10.1002/dvdy.20986) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maung SM, Jenny A. 2011. Planar cell polarity in Drosophila. Organogenesis 7, 165–179. ( 10.4161/org.7.3.18143) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hashimoto M, et al. 2010. Planar polarization of node cells determines the rotational axis of node cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 170–176. ( 10.1038/ncb2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song H, Hu J, Chen W, Elliott G, Andre P, Gao B, Yang Y. 2010. Planar cell polarity breaks bilateral symmetry by controlling ciliary positioning. Nature 466, 378–382. ( 10.1038/nature09129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Antic D, Stubbs JL, Suyama K, Kintner C, Scott MP, Axelrod JD. 2010. Planar cell polarity enables posterior localization of nodal cilia and left-right axis determination during mouse and Xenopus embryogenesis. PLoS ONE 5, e8999 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0008999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hashimoto M, Hamada H. 2010. Translation of anterior-posterior polarity into left-right polarity in the mouse embryo. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20, 433–437. ( 10.1016/j.gde.2010.04.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hirokawa N, Tanaka Y, Okada Y. 2012. Cilia, KIF3 molecular motor and nodal flow. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24, 31–39. ( 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.01.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beckers A, Alten L, Viebahn C, Andre P, Gossler A.2007. The mouse homeobox gene Noto regulates node morphogenesis, notochordal ciliogenesis, and left right patterning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15765–15770. ( ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Haaning AM, Quinn ME, Ware SM. 2013. Heterotaxy-spectrum heart defects in Zic3 hypomorphic mice. Pediatr. Res. 74, 494–502. ( 10.1038/pr.2013.147) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sutherland MJ, Wang S, Quinn ME, Haaning A, Ware SM. 2013. Zic3 is required in the migrating primitive streak for node morphogenesis and left-right patterning. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 1913–1923. ( 10.1093/hmg/ddt001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boskovski MT, Yuan S, Pedersen NB, Goth CK, Makova S, Clausen H, Brueckner M, Khokha MK. 2013. The heterotaxy gene GALNT11 glycosylates Notch to orchestrate cilia type and laterality. Nature 504, 456–459. ( 10.1038/nature12723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang G, Manning ML, Amack JD. 2012. Regional cell shape changes control form and function of Kupffer's vesicle in the zebrafish embryo. Dev. Biol. 370, 52–62. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Compagnon J, Barone V, Rajshekar S, Kottmeier R, Pranjic-Ferscha K, Behrndt M, Heisenberg C-P. 2014. The notochord breaks bilateral symmetry by controlling cell shapes in the zebrafish laterality organ. Dev. Cell 31, 774–783. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fakhro KA, Choi M, Ware SM, Belmont JW, Towbin JA, Lifton RP, Khokha MK, Brueckner M. 2011. Rare copy number variations in congenital heart disease patients identify unique genes in left-right patterning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2915–2920. ( 10.1073/pnas.1019645108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee JD, Migeotte I, Anderson KV. 2010. Left-right patterning in the mouse requires Epb4.1l5-dependent morphogenesis of the node and midline. Dev. Biol. 346, 237–246. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.07.029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pulina MV, Hou SY, Mittal A, Julich D, Whittaker CA, Holley SA, Hynes RO, Astrof S. 2011. Essential roles of fibronectin in the development of the left-right embryonic body plan. Dev. Biol. 354, 208–220. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.03.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pulina M, Liang D, Astrof S. 2014. Shape and position of the node and notochord along the bilateral plane of symmetry are regulated by cell-extracellular matrix interactions. Biol. Open 3, 583–590. ( 10.1242/bio.20148243) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yin Y, et al. 2009. The Talpid3 gene (KIAA0586) encodes a centrosomal protein that is essential for primary cilia formation. Development 136, 655–664. ( 10.1242/dev.028464) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stephen LA, Davis GM, McTeir KE, James J, McTeir L, Kierans M, Bain A, Davey Megan G. 2013. Failure of centrosome migration causes a loss of motile cilia in talpid3 mutants. Dev. Dyn. 242, 923–931. ( 10.1002/dvdy.23980) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bangs F, Antonio N, Thongnuek P, Welten M, Davey MG, Briscoe J, Tickle C. 2011. Generation of mice with functional inactivation of talpid3, a gene first identified in chicken. Development 138, 3261–3272. ( 10.1242/dev.063602) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gros J, Feistel K, Viebahn C, Blum M, Tabin CJ. 2009. Cell movements at Hensen's node establish left/right asymmetric gene expression in the chick. Science 324, 941–944. ( 10.1126/science.1172478) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schroder SS, Tsikolia N, Weizbauer A, Hue I, Viebahn C. 2016. Paraxial nodal expression reveals a novel conserved structure of the left-right organizer in four mammalian species. Cells Tissues Organs. 201, 77–87. ( 10.1159/000440951) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vandenberg LN, Levin M. 2010. Far from solved: a perspective on what we know about early mechanisms of left-right asymmetry. Dev. Dyn. 239, 3131–3146. ( 10.1002/dvdy.22450) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blum M, Schweickert A, Vick P, Wright CV, Danilchik MV. 2014. Symmetry breakage in the vertebrate embryo: when does it happen and how does it work? Dev. Biol. 393, 109–123. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.06.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kramer KL, Barnette JE, Yost HJ. 2002. PKCgamma regulates syndecan-2 inside-out signaling during Xenopus left-right development. Cell 111, 981–990. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01200-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kramer KL, Yost HJ. 2002. Ectodermal syndecan-2 mediates left-right axis formation in migrating mesoderm as a cell-nonautonomous Vg1 cofactor. Dev. Cell 2, 115–124. ( 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00107-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aw S, Adams DS, Qiu D, Levin M. 2008. H,K-ATPase protein localization and Kir4.1 function reveal concordance of three axes during early determination of left-right asymmetry. Mech. Dev. 125, 353–372. ( 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Adams DS, Robinson KR, Fukumoto T, Yuan S, Albertson RC, Yelick P, Kuo L, McSweeney M, Levin M. 2006. Early, H+-V-ATPase-dependent proton flux is necessary for consistent left-right patterning of non-mammalian vertebrates. Development 133, 1657–1671. ( 10.1242/dev.02341) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fukumoto T, Kema IP, Levin M. 2005. Serotonin signaling is a very early step in patterning of the left-right axis in chick and frog embryos. Curr. Biol. 15, 794–803. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.044) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vandenberg LN, Lemire JM, Levin M. 2013. It's never too early to get it Right: A conserved role for the cytoskeleton in left-right asymmetry. Commun. Integr. Biol. 6, e27155 ( 10.4161/cib.27155) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lobikin M, Wang G, Xu J, Hsieh YW, Chuang CF, Lemire JM, Levin M.. 2012. Early, nonciliary role for microtubule proteins in left-right patterning is conserved across kingdoms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12586–12591. ( 10.1073/pnas.1202659109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Armakolas A, Klar AJ. 2007. Left-right dynein motor implicated in selective chromatid segregation in mouse cells. Science 315, 100–101. ( 10.1126/science.1129429) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vandenberg LN, Levin M. 2013. A unified model for left-right asymmetry? Comparison and synthesis of molecular models of embryonic laterality. Dev. Biol. 379, 1–15. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.03.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schweickert A, Walentek P, Thumberger T, Danilchik M. 2012. Linking early determinants and cilia-driven leftward flow in left-right axis specification of Xenopus laevis: a theoretical approach. Differentiation 83, S67–S77. ( 10.1016/j.diff.2011.11.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arrington CB, Peterson AG, Yost HJ. 2013. Sdc2 and Tbx16 regulate Fgf2-dependent epithelial cell morphogenesis in the ciliated organ of asymmetry. Development 140, 4102–4109. ( 10.1242/dev.096933) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen Y, et al. 2012. A SNX10/V-ATPase pathway regulates ciliogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Cell Res. 22, 333–345. ( 10.1038/cr.2011.134) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gokey JJ, Dasgupta A, Amack JD. 2015. The V-ATPase accessory protein Atp6ap1b mediates dorsal forerunner cell proliferation and left-right asymmetry in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 407, 115–130. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walentek P, Beyer T, Thumberger T, Schweickert A, Blum M. 2012. ATP4a is required for Wnt-dependent Foxj1 expression and leftward flow in Xenopus left-right development. Cell Rep. 1, 516–527. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Beyer T, et al. 2012. Serotonin signaling is required for Wnt-dependent GRP specification and leftward flow in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 22, 33–39. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cooper MS, D'Amico LA. 1996. A cluster of noninvoluting endocytic cells at the margin of the zebrafish blastoderm marks the site of embryonic shield formation. Dev. Biol. 180, 184–198. ( 10.1006/dbio.1996.0294) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Melby AE, Warga RM, Kimmel CB. 1996. Specification of cell fates at the dorsal margin of the zebrafish gastrula. Development 122, 2225–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chung WS, Stainier DY. 2008. Intra-endodermal interactions are required for pancreatic beta cell induction. Dev. Cell 14, 582–593. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oteiza P, Koppen M, Concha ML, Heisenberg CP. 2008. Origin and shaping of the laterality organ in zebrafish. Development 135, 2807–2813. ( 10.1242/dev.022228) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Methods and data supporting figure 2 have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.