Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine the effect of once-yearly zoledronic acid on the number of days of back pain and the number of days of disability (ie, limited activity and bed rest) owing to back pain or fracture in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 240 clinical centers in 27 countries. Participants included 7736 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Patients were randomized to receive either a single 15-minute intravenous infusion of zoledronic acid (5 mg) or placebo at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. The main outcome measures were self-reported number of days with back pain and the number of days of limited activity and bed rest owing to back pain or a fracture, and this was assessed every 3 months over a 3-year period. Our results show that although the incidence of back pain was high in both randomized groups, women randomized to zoledronic acid experienced, on average, 18 fewer days of back pain compared with placebo over the course of the trial (p = .0092). The back pain among women randomized to zoledronic acid versus placebo resulted in 11 fewer days of limited activity (p = .0017). In Cox proportional-hazards models, women randomized to zoledronic acid were about 6% less likely to experience 7 or more days of back pain [relative risk (RR) = 0.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.90–0.99] or limited activity owing to back pain (RR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.87–1.00). Women randomized to zoledronic acid were significantly less likely to experience 7 or more bed-rest days owing to a fracture (RR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.47–0.72) and 7 or more limited-activity days owing to a fracture (RR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.58–0.78). Reductions in back pain with zoledronic acid were independent of incident fracture. Our conclusion is that in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, a once-yearly infusion with zoledronic acid over a 3-year period significantly reduced the number of days that patients reported back pain, limited activity owing to back pain, and limited activity and bed rest owing to a fracture.

Keywords: BACK PAIN, DISABILITY, FRACTURE, POSTMENOPAUSAL OSTEOPOROSIS, ZOLEDRONIC ACID

Introduction

Osteoporotic fractures have a number of important consequences, including back pain, disability, and death.(1) Women with prevalent vertebral fractures complain of back pain and limitations in physical function.(2–4) Incident vertebral fractures, even if not clinically recognized, also result in an increase in back-related disability and bed-rest days.(5,6) Women who experience a hip fracture are 50% less likely to walk independently or achieve their prefracture ability to carry out their activities of daily living.(7) The estimated functional decline specifically attributed to hip fractures was 24% during the first year following a hip fracture.(8) Quality of life (QOL) also was shown to be compromised in women with incident nonvertebral fractures.(9) The decrease in QOL was found for all domains, including symptoms, physical functioning, and activities of daily living.(9) Alendronate has been shown to reduce the number of bed-rest days and limited-activity days relative to placebo(10) in women with prevalent vertebral fractures. Hormone therapy has reduced clinical fractures, including hip fractures,(11) but with no effect on QOL.(12)

The Health Outcomes and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic Acid Once Yearly (HORIZON) Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT) was an international, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled three-year trial involving 7736 women with established osteoporosis. Zoledronic acid was found to significantly reduce vertebral, hip, and all clinical fractures by 70%, 41%, and 33%, respectively.(13) We present the findings of a prespecified subanalysis of the HORIZON trial to determine the effects of zoledronic acid on the number of days of back pain and the number of days of disability (limited activity and bed rest) owing to back pain or a fracture.

Methods

Study design

Women were randomized to receive either a 15-minute intravenous administration of zoledronic acid (5 mg) or placebo at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. In addition, all patients received oral daily calcium (1000 to 1500 mg) and vitamin D (400 to 1200 IU). Patients were monitored for three years with quarterly telephone interviews and clinic visits at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

Study population

Details of recruitment and inclusion criteria for the HORIZON-PFT have been published previously.(13) The trial was conducted at 240 clinical centers in 27 countries. All women in the HORIZON trial were between the ages of 65 and 89 years, postmenopausal, and had a femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of −2.5 or less with or without evidence of existing vertebral fractures or a T-score of −1.5 or less with radiologic evidence of at least two mild or one moderate vertebral fracture. Prior bisphosphonate use was allowed, with the duration of washout period depending on duration of previous use. Subjects were placed into one of two strata on the basis of whether they were taking any osteoporosis medications at baseline. Women in stratum 1 were not taking any osteoporosis medications. Women in stratum 2 were allowed to use the following medications: hormone therapy, raloxifene, calcitonin, tibolone, tamoxifen, dehydroepiandrosterone, ipriflavone, and medroxyprogester-one. Exclusion criteria have been described previously.(13) The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and local applicable laws and regulations. Approval was obtained from an Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee for each participating study center. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Main outcome measures

The main outcome measures of number of days of back pain and number of days of disability owing to back pain or fracture were developed originally for the Fracture Intervention Trial.(10) Every 3 months, all subjects were asked specific questions about back pain. We ascertained whether the subject had any back pain and, if so, the number of days and severity of the back pain (moderate or worse, severe, or very severe) over the past 3 months. The number of back pain days, number of days with moderate or worse back pain, and number of days with severe or worse back pain were totaled over the course of the study. We determined whether the subjects limited their activities owing to back pain or spent more than a half a day in bed because of back pain. The number of limited-activity days and bed-rest days were recorded for each 3-month period and totaled over the entire study. Subjects who answered “No” to the back pain questions were assigned a zero for that assessment.

Information about days of limited activity and bed rest owing to a fracture was obtained from subjects who experienced a clinical fracture during the study. If the subjects had a clinical fracture at any time over the course of the study, two questions were asked: “In the past 3 months, how many weeks (or days) altogether did you reduce your usual activities because of a fracture?” and “In the past 3 months, how many weeks (or days) did you stay in bed for more than half a day because of a fracture?” The number of days of reduced activity and bed rest owing to a fracture was totaled and referred to as limited-activity days and bed-rest days.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were prespecified and approved by the HORIZON steering committee. We included all subjects in the intent-to-treat population. Characteristics of women at baseline by randomization were compared by t test (continuous if normally distributed), Wilcoxon rank-sum test (continuous if not normally distributed), or chi-square (categorical) tests.

The seven response variables were number of days with back pain, moderate or worse (on average) back pain, severe or worse (on average) back pain, limited activity owing to back pain, bed rest owing to back pain, limited activity owing to a fracture, and bed rest owing to a fracture. Women were categorized according to mean number of days (<7 days versus ≥7 days), similar to the approach used in the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT).(10)

One-way ANOVA was used for continuous outcome models to test the hypothesis that zoledronic acid reduced the number of back pain days and the number of bed-rest and limited-activity days owing to back pain or following a fracture relative to placebo. Cox proportional-hazards (Cox PH) models were used to compute the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and to test the hypothesis that zoledronic acid reduces the incidence of 7 or more days of back pain, bed rest, and limited activity. Cumulative days of disability were summed across quarterly reports; when the sum reached seven or more (not necessarily in the same quarter), this was used as the time to event. Patients without back pain were not excluded, and follow-up time was the entire length of the study. Unadjusted Cox models were evaluated first. Subsequent Cox PH models adjusted for age, back pain at baseline, baseline prevalent vertebral fracture, and total-hip BMD (model one). In model 2, we additionally adjusted for whether or not an incident morphometric vertebral fracture occurred over the course of the study (time dependent to nearest year). In model 3, we additionally adjusted for whether a clinical vertebral fracture had occurred (time dependent to nearest quarter). In models 2 and 3, we were testing the hypothesis that if zoledronic acid reduces back pain, limited-activity days, and bed-rest days, it is due to a reduction in fractures, and we would observe some attenuation in the RR for zoledronic acid.

Results

A total of 7736 women were randomly assigned to either zoledronic acid (n = 3875) or placebo (n = 3861; Table 1). The mean age of the subjects was 73 years and did not differ by randomized group; 79% of the women were white, and about 63% had at least one prevalent vertebral fracture at baseline. At baseline, 73% of those randomized to zoledronic acid and 72% of those randomized to placebo reported back pain; in each treatment group, 52% reported that their back pain was moderate and 18% severe or very severe.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics for the Intent-to-Treat Population by Randomization Group (n [%] or mean ± SD)

| Zoledronic acid (n = 3875) | Placebo (n = 3861) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73.1 ± 5.3 | 73.0 ± 5.4 |

| Race | ||

| White | 3054 (78.8%) | 3055 (79.1%) |

| Black | 15 (0.4%) | 17 (0.4%) |

| Hispanic | 226 (5.8%) | 215 (5.6%) |

| Japanese | 9 (0.2%) | 12 (0.3%) |

| Other Asian | 553 (14.3%) | 547 (14.2%) |

| Other | 18 (0.5%) | 15 (0.4%) |

| Height(cm) | 154 ± 7.1 | 154 ± 7.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.9 ± 11.1 | 60.6 ± 11.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.1 ± 4.3 | 25.4 ± 4.3 |

| Prevalent vertebral fractures | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 2416 (62.4%) | 2477 (64.2%) |

| Back pain (baseline) | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 2807 (72.9%) | 2783 (72.4%) |

| Of those, frequency of back pain | ||

| All or most of the time | 1190 (42.4%) | 1178 (42.4%) |

| Of those, severity of back pain | ||

| Very mild | 140 (5.0%) | 149 (5.4%) |

| Mild | 698 (24.9%) | 694 (24.9%) |

| Moderate | 1464 (52.2%) | 1447 (52.0%) |

| Severe/very severe | 505 (18.0%) | 493 (17.8%) |

| Number of days with back pain | ||

| n | 3863 | 3849 |

| Mean | 33.9 (36.4) | 33.5 (36.3) |

Back pain

At the end of the 3-year trial, 56.6% and 59.5% of women randomized to zoledronic acid and placebo, respectively, reported any back pain (p = .014). The mean number of days with any back pain, moderate or worse back pain, and severe or worse back pain was lower in women randomized to zoledronic acid compared with placebo (Table 2). For example, women treated with zoledronic acid reported 18 fewer days of back pain compared with placebo. The percentage of women who experienced 7 or more days of any back pain was high in both the zoledronic acid and placebo groups (>80%); nevertheless, women randomized to zoledronic acid were about 6% less likely to experience 7 or more days of back pain (p = .02).

Table 2.

Average Number of Days and n (%) of Women Experiencing ≥7 Days of Back Pain by Treatment and Prevalent Vertebral Fracture

| Back pain

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any back pain

|

Moderate or worse

|

Severe or worse

|

||||

| Days, mean ± SDa | ≥7 days, n (%) of womenb | Days, mean ± SDa | ≥7 days, n (%) of womenb | Days, mean ± SDa | ≥7 days, n (%) of womenb | |

| Overall treatment | 272.5 ± 303.1 | 6450 (83.6) | 202.6 ± 278.8 | 5280 (68.4) | 46.4 ± 134.1 | 1978 (25.6) |

| Zoledronic acid | 263.6 ± 299.8 | 3190 (82.6) | 194.9 ± 274.4 | 2598 (67.3) | 44.5 ± 130.2 | 948 (24.6) |

| Placebo | 281.5 ± 306.2 | 3260 (84.6) | 210.3 ± 283.1 | 2682 (69.6) | 48.4 ± 138.0 | 1030 (26.7) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −18.0 (−31.5, −4.4) | −15.4 (−27.9, −3.0) | −3.9 (−9.9, 2.1) | |||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) | 0.95 (0.90,1.00) | 0.92 (0.84,1.00) | |||

| p Value | .009 | .020 | .015 | .049 | .198 | .059 |

| Prevalent vertebral fracture (Yes) | ||||||

| Total | 294.2 ± 312.2 | 4155 (85.2) | 219.6 ± 289.5 | 3441 (70.5) | 51.2 ± 141.7 | 1327 (27.2) |

| Zoledronic acid | 284.7 ± 311.2 | 2011 (83.5) | 212.1 ± 286.4 | 1653 (68.6) | 49.2 ± 137.2 | 629 (26.1) |

| Placebo | 303.4 ± 313.0 | 2144 (86.8) | 226.9 ± 292.3 | 1788 (72.4) | 53.3 ± 146.1 | 698 (28.2) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −18.8 (−36.3, −1.2) | −14.9 (−31.1, 1.4) | −4.1 (−12.1, 3.9) | |||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 0.93 (0.83, 1.03) | |||

| p value | .036 | .018 | .073 | .026 | .313 | .161 |

| Prevalent vertebral fracture (No) | ||||||

| Total | 235.2 ± 283.0 | 2292 (80.9) | 173.2 ± 256.8 | 1836 (64.8) | 38.0 ± 119.4 | 648 (22.9) |

| Zoledronic acid | 228.7 ± 276.7 | 1177 (81.1) | 166.5 ± 250.9 | 943 (65.0) | 36.6 ± 117.5 | 317 (21.8) |

| Placebo | 242.0 ± 289.3 | 1115 (80.7) | 180.2 ± 262.8 | 893 (64.7) | 39.5 ± 121.5 | 331 (24.0) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −13.3 (−34.2, 7.5) | −13.7 (−32.6, 5.2) | −2.9 (−11.7, 5.9) | |||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.98 (0.90,1.06) | 0.99 (0.91,1.09) | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | |||

| p Value | .210 | .611 | .156 | .910 | .522 | .233 |

SD = standard deviation; LS = least squares; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

LS mean difference and p value are calculated using one-way ANOVA.

RR and p value are calculated using Cox regression.

Women randomized to zoledronic acid experienced 15 fewer days with moderate to severe back pain than women in the placebo group (p = .015). There was no significant difference in the number of days with severe or worse back pain by treatment group. Women randomized to zoledronic acid were 5% less likely to report 7 or more days of moderate to severe back pain (p = .049) and 8% less likely to report 7 or more days of severe or worse back pain (p = .059).

Among women with a prevalent vertebral fracture at baseline, women randomized to zoledronic acid reported, on average, 19 fewer days of back pain (p = .0359) and were 7% less likely to report 7 or more days of back pain compared with placebo (p = .018). Women with a baseline prevalent vertebral fracture and randomized to zoledronic acid also reported 15 fewer days of moderate to severe back pain (p = .073) and 4 fewer days of severe to worse back pain (p = .31), but neither difference reached statistical significance. Nevertheless, women randomized to zoledronic acid were 7% less likely to report 7 or more days of moderate to severe back pain (p = .026).

Overall, the number of days with any back pain was lower in women who did not have a prevalent vertebral fracture at baseline (p = .036). Among these women without a prevalent vertebral fracture at baseline, the women randomized to zoledronic acid reported fewer days of back pain, on average, but the difference was not significant (p = .210).

We also examined the number of days of limited activity and bed rest owing to back pain by randomized group (Table 3). Women randomized to zoledronic acid, on average, reported 61 days of limited activity owing to back pain compared with 72 days among women randomized to placebo (p = .002). The relative risk of experiencing 7 or more days of limited activity owing to back pain was 0.94 (95% CI 0.87–1.00, p = .067) for women in the zoledronic acid group compared with the placebo group.

Table 3.

Average Number of Days and n (%) of Women Experiencing ≥7 Days of Limited Activity and Bed Rest Owing to Back Pain by Treatment Group and Vertebral Fracture Status at Baseline

| Effect of back pain

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited activity

|

Bed rest

|

|||

| Days, mean ± SDa | ≥7 days, n (%) of womenb | Days, mean ± SDa | ≥7 days, n (%) of womenb | |

| Overall | 66.2 ± 159.1 | 3017 (39.1) | 8.7 ± 46.2 | 913 (11.8) |

| Treatment | ||||

| Zoledronic acid | 60.5 ± 149.7 | 1464 (37.9) | 8.2 ± 45.1 | 429 (11.1) |

| Placebo | 71.9 ± 167.8 | 1553 (40.3) | 9.2 ± 47.2 | 484 (12.6) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)* | −11.4 (−18.5, −4.3) | −1.0 (−3.1, 1.0) | ||

| RR (95% CI)† | 0.94 (0.87, 1.00) | 0.89 (0.78, 1.01) | ||

| p value | .002 | .067 | .332 | .082 |

| Vertebral fracture at baseline (Yes) | ||||

| Total | 76.4 ± 170.8 | 2086 (42.8) | 11.2 ± 52.8 | 699 (14.3) |

| Zoledronic acid | 69.4 ± 159.4 | 994 (41.3) | 10.5 ± 53.0 | 320 (13.3) |

| Placebo | 83.3 ± 180.9 | 1092 (44.2) | 11.9 ± 52.7 | 379 (15.3) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −14.0(−23.5, −4.4) | −1.4 (−4.3, 1.6) | ||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01) | 0.87 (0.75, 1.01) | ||

| p Value | .004 | .089 | .368 | .072 |

| Vertebral fracture at baseline (No) | ||||

| Total | 48.4 ± 134.7 | 928 (32.8) | 4.4 ± 31.2 | 213 (7.5) |

| Zoledronic acid | 45.9 ± 130.9 | 468 (32.3) | 4.3 ± 27.1 | 108 (7.4) |

| Placebo | 51.1 ± 138.5 | 460 (33.3) | 4.5 ± 35.0 | 105 (7.6) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −5.3 (−15.2, 4.7) | −0.1 (−2.4, 2.2) | ||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 0.99 (0.76, 1.30) | ||

| p Value | .300 | .611 | .909 | .943 |

SD = standard deviation; LS = least squares; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

LS mean difference and p value are calculated using one-way ANOVA.

RR and p value are calculated using Cox regression.

The effect of zoledronic acid on limited-activity days owing to back pain was confined to women with a prevalent vertebral fracture. Women with a prevalent vertebral fracture randomized to zoledronic acid reported 14 fewer days of limited activity owing to back pain compared with placebo (p = .004) and were 7% less likely to report 7 or more days of limited activity owing to back pain (p = .089). There was no difference in the average number or percent of women reporting 7 or more limited-activity days owing to back pain among women who did not have a prevalent vertebral fracture at study entry.

Overall, the average number of bed-rest days owing to back pain was low in both randomized groups and, as expected, was higher among women with a prevalent vertebral fracture at baseline. The average number of bed-rest days owing to back pain did not differ by randomized group, but there was some suggestion that fewer women who had a prevalent vertebral fracture and were randomized to zoledronic acid experienced 7 or more days of bed rest owing to back pain, but these observations did not reach significance (p = .072).

Disability owing to fracture

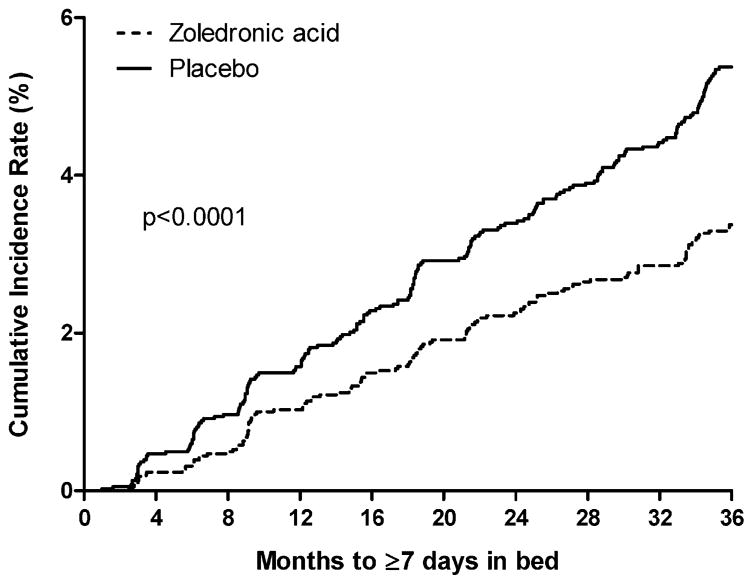

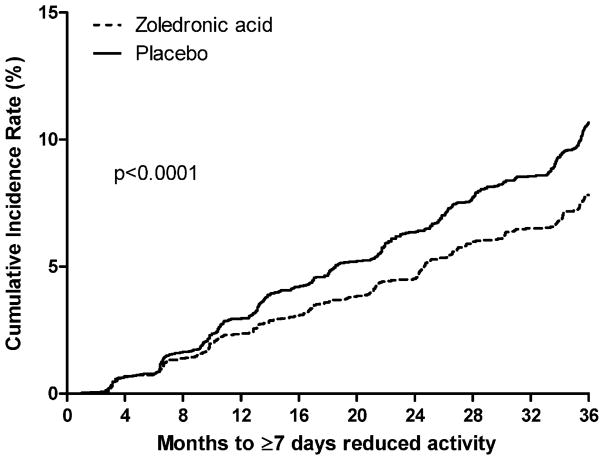

Over the 3-year trial, 316 women in the zoledronic acid group and 466 in the placebo group reported a clinical fracture. The cumulative incidence of experiencing 7 or more days in bed or limited activity owing to a fracture was lower among women randomized to zoledronic acid compared with placebo (both p <.0001; Figs. 1 and 2). The average number of limited-activity days after a fracture was 6 days in women randomized to zoledronic acid compared with 10 in the placebo group (p <.0001; Table 4). The average number of bed-rest days after a fracture was lower in women randomized to zoledronic acid, but the difference was not significant (p <.110).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative probability of experiencing at least 7 days in bed owing to fracture.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative probability of experiencing at least 7 days of reduced activity owing to fracture.

Table 4.

Average Number of Days and n (%) of Women Experiencing ≥7 Days of Limited Activity and Bed Rest After A Fracture by Treatment Group and Vertebral Fracture at Baseline

| Days of limited activity after fracture

|

Days of bed rest after fracture

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days, mean ± SDa | ≥7 days, n (%) of womenb | Days, mean ± SDa | ≥7 days, n (%) of womenb | |

| Overall | 7.9 ± 38.3 | 782 (10.2) | 1.9 ± 15.5 | 348 (4.5) |

| Treatment | ||||

| ZOL | 5.9 ± 33.7 | 316 (8.2) | 1.6 ± 15.3 | 127 (3.3) |

| Placebo | 9.9 ± 42.3 | 466 (12.1) | 2.2 ± 15.7 | 221 (5.7) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −4.0 (−5.7, −2.3) | −0.6 (−1.3, 0.1) | ||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.67 (0.58, 0.78) | 0.58 (0.47, 0.72) | ||

| p Value | <.0001 | <.0001 | .110 | <.0001 |

| Vertebral fracture at baseline (Yes) | ||||

| Total | 8.8 ± 40.8 | 544 (11.2) | 2.3 ± 18.1 | 259 (5.3) |

| ZOL | 6.5 ± 36.3 | 211 (8.8) | 2.0 ± 18.1 | 94 (3.9) |

| Placebo | 11.1 ± 44.6 | 333 (13.5) | 2.6 ± 18.2 | 165 (6.7) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −4.7 (−6.9, −2.4) | −0.6 (−1.6, 0.4) | ||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.64 (0.54, 0.77) | 0.59 (0.46, 0.76) | ||

| p Value | .0001 | <.0001 | .248 | <.0001 |

| Vertebral fracture at baseline (No) | ||||

| Total | 6.3 ± 33.5 | 238 (8.4) | 1.2 ± 9.2 | 89 (3.1) |

| ZOL | 5.0 ± 28.9 | 105 (7.2) | 0.9 ± 8.7 | 33 (2.3) |

| Placebo | 7.8 ± 37.8 | 133 (9.7) | 1.4 ± 9.6 | 56 (4.1) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI)a | −2.7 (−5.2, −0.3) | −0.4 (−1.1, 0.2) | ||

| RR (95% CI)b | 0.75 (0.58, 0.97) | 0.58 (0.37, 0.89) | ||

| p Value | .030 | .023 | .198 | .012 |

SD = standard deviation; LS = least squares; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

LS mean difference and p value are calculated using one-way ANOVA.

RR and p value are calculated using Cox regression.

Women randomized to zoledronic acid were 42% and 33% less likely to report 7 or more days of bed rest and limited activity, respectively, following a fracture compared with placebo (both p <.0001; Table 4). Similar results were observed in women with and without a prevalent vertebral fracture. Women with and without a prevalent vertebral fracture, respectively, randomized to zoledronic acid, were 41% (p <.0001) and 42% (p = .0122) less likely to report 7 or more days of bed rest after a fracture and 36% (p <.0001) and 25% (p = .0296) less likely to report 7 or more days of limited activity after a fracture.

Multivariate analysis

Women randomized to zoledronic acid were 10% less likely to report 7 or more days of back pain compared with women in the placebo group (p <.001; Table 5). This association was independent of age, back pain at baseline, prevalent vertebral fracture, total-hip BMD, and whether or not the woman experienced an incident morphometric or clinical spine fracture. Analyses by severity of back pain generally were similar to the overall back pain results.

Table 5.

Relative Risk (RR) of Limited Activity, Bed Rest, and Back Pain by Treatment Group: Unadjusted and Multivariate Models

| RR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| ≥7 days back pain | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) | .020 |

| Model 1 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.96) | .0003 |

| Model 2 | 0.90 (0.85, 0.95) | <.0001 |

| Model 3 | 0.90 (0.85, 0.95) | <.0001 |

| ≥7 days moderate or worse back pain days | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | .049 |

| Model 1 | 0.94 (0.89, 0.99) | .020 |

| Model 2 | 0.93 (0.87, 0.98) | .010 |

| Model 3 | 0.93 (0.88, 0.99) | .016 |

| ≥7 days severe or worse back pain days | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) | .059 |

| Model 1 | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | .078 |

| Model 2 | 0.90 (0.82, 0.99) | .040 |

| Model 3 | 0.93 (0.84, 1.02) | .135 |

| ≥7 days bed rest owing to back pain | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.89 (0.78, 1.01) | .082 |

| Model 1 | 0.89 (0.78, 1.02) | .087 |

| Model 2 | 0.86 (0.74, 0.99) | .034 |

| Model 3 | 0.92 (0.79, 1.06) | .240 |

| ≥7 limited-activity days owing to back pain | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.94 (0.87, 1.00) | .067 |

| Model 1 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.01) | .086 |

| Model 2 | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | .028 |

| Model 3 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | .124 |

| ≥7 bed-rest days after fracture | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.58 (0.47, 0.72) | <.0001 |

| Model 1 | 0.59 (0.47, 0.73) | <.0001 |

| Model 2 | 0.52 (0.41, 0.67) | <.0001 |

| Model 3 | 0.62 (0.48, 0.80) | .0002 |

| ≥7 limited-activity days after fracture | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.67 (0.58, 0.78) | <.0001 |

| Model 1 | 0.68 (0.59, 0.78) | <.0001 |

| Model 2 | 0.64 (0.55, 0.75) | <.0001 |

| Model 3 | 0.73 (0.62, 0.85) | <.0001 |

CI = confidence interval

Cox regression:

Model 1 = age, back pain at baseline, baseline prevalent vertebral fracture, total-hip BMD.

Model 2 = Model 1 + incident morphometric vertebral fracture during the study (time dependent).

Model 3 = Model 2 + incident clinical vertebral fracture (time dependent).

Adjusting for incident morphometric vertebral fracture (model 2), women randomized to zoledronic acid also were significantly less likely to report 7 or more days of bed rest or limited activity owing to back pain (p = .0344 and .0281, respectively). However, further adjustment for a new clinical vertebral fracture attenuated these associations.

Women randomized to zoledronic acid were at least 38% and 27% less likely to report 7 or more days of bed-rest and limited-activity days after a fracture, respectively, compared with placebo (all p <.001). These results were independent of whether or not an incident vertebral fracture (models 2 and 3) had occurred over the course of the study.

Among women who did not experience an incident clinical fracture or an incident morphometric spine fracture, there was no difference in the number of days with back pain (p = .58), number of limited-activity days owing to back pain (p = .23), or the number of bed-rest days owing to back pain (p = .97) by treatment group (data not shown).

Discussion

Treatment with zoledronic acid significantly reduced the number of days with back pain and the number of days of limited activity owing to back pain in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Women randomized to zoledronic acid experienced 18 fewer days of back pain, and the percentage of women reporting 7 or more days of back pain was reduced by 6% compared with placebo. This effect was greatest among women who had a prevalent vertebral fracture when they entered the study. Women randomized to zoledronic acid also reported 11 fewer days of limited activity owing to back pain compared with placebo and were less likely to report 7 or more days of bed rest owing to back pain, although this latter result was only borderline significant, perhaps reflecting lower power to see an effect because only 10% to 12% of women reported 7 or more days of bed rest owing to back pain. The results suggest a modest, albeit significant reduction in back pain and back pain–related disability for women randomized to zoledronic acid.

Disability after fracture was 30% to 40% lower among women treated with zoledronic acid. Women randomized to zoledronic acid were significantly less likely to report 7 or more days of limited activity and bed rest after a fracture compared with placebo. The lower disability postfracture in women on zoledronic acid was observed in women with and without a baseline vertebral fracture and was independent of whether or not an incident morphometric or clinical vertebral fracture occurred during the trial. This effect may reflect the reduction in all clinical fractures observed with zoledronic acid during the trial or may suggest that the fractures among women on zoledronic acid were less severe.

Chronic back pain may be caused directly by the vertebral fracture. Adjustment for incident clinical or morphometric vertebral fracture actually strengthened the association with back pain but attenuated the association with disability associated with back pain. Back pain also may occur because of the associated skeletal deformities, joint incongruity, and tension on muscle and tendons. Guarded movement and fear of back pain also may lead to physical deconditioning and disability.(14)

Our results are consistent with findings from the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT), where alendronate therapy for 3 years reduced the number of days of back pain and limited activity owing to back pain among women with a prevalent vertebral fracture.(10) The average number of days of back pain and limited activity owing to back pain were similar in both the FIT and HORIZON trials. A higher number of bed-rest days owing to back pain was observed in the HORIZON trial, perhaps reflecting the older age of study participants. Other osteoporosis treatments that have been shown to reduce back pain include teriparatide treatment.(15,16) A meta-analysis of five randomized trials showed that teriparatide (20 or 40 μg/d) reduced the risk of any back pain by 34%, moderate or severe back pain by 40%, and severe back pain by 54% compared with a pooled comparison group that consisted of placebo, alendronate, or hormone therapy. The median length of the trials was 11 to 20 months, and participants, on average, were much younger (58 to 70 years) than the women in the HORIZON trial.(16) A systematic review of five randomized trials showed that calcitonin significantly reduced the severity of acute pain from osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures and shortened the time to mobilization.(17) The underlying mechanism for its analgesic effect may be an increase in β-endorphin levels,(18) and calcitonin may have no effect on the chronic pain associated with osteoporosis.(19) A major limitation of both these meta-analyses was that information on back pain was not collected systematically in the trials and was assessed only using the adverse-events database, which may reflect more severe back pain.

This prespecified subanalysis of a large, global randomized trial of once-yearly zoledronic acid allowed for the systematic collection of information on back pain and disability days related to back pain and fracture over a 3-year period. However, a limitation of this study was that severity of back pain was assessed by a simple question about the strength of the pain, and a visual analog scale was not used to rate the intensity of the back pain. In addition, we had no information on the severity of the clinical fractures.

In conclusion, osteoporotic fractures have a number of important consequences, including back pain, disability, and death.(1) Hip fractures, vertebral fractures, and wrist fractures all have been shown to increase the risk of disability.(5,7,8,20) In addition to the reduction in vertebral, hip, and all clinical fractures reported previously with zoledronic acid in the HORIZON-PFT,(13) 3-year treatment with zoledronic acid significantly reduced the number of days that patients reported back pain, limited activity owing to back pain, and limited activity and bed rest after a fracture in comparison with placebo in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due Zeb Horowitz (now at Savient Pharmaceuticals), John Orloff (Novartis), and the following Steering Committee members: Dennis Black, Steven Cummings, Pierre Delmas, Richard Eastell, Ian Reid, Steven Boonen (senior clinical investigator of the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders, Belgium (F.W.O. Vlaanderen), and holder of the Leuven University Chair in Gerontology and Geriatrics), Jane Cauley, Felicia Cosman, Péter Lakatos, Ping C Leung, and Zulema Man; past Steering Committee members: Edith Lau, Saloman Jasqui, Carlos Mautalen, Theresa Rosario-Jansen (Novartis), John Caminis (Novartis), Erik Fink Eriksen, Peter Mesenbrink (Novartis); Data Safety Monitoring Board: Lawrence Raisz (chairman), Peter Bauer, Juliet Compston, David DeMets, Raimund Hirschberg, Olof Johnell, Stuart Ralston, Robert Wallace; DSMB consultants: Michael Farkough; Novartis: Mary Flood; University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Coordinating Center: Douglas Bauer, Lisa Palermo; and UCSF Radiology (QCT analysis): Thomas Lang. We are also indebted to the HORIZON-PFT clinical site investigators: Argentina: Eduardo Kerzberg, Zulema Man, Carlos Mautalen, Maria Ridruejo, Guillermo Tate, Jorge Velasco; Australia: Michael Hooper, Mark Kotowicz, Peter Nash, Richard Prince, Anthony Roberts, Philip Sambrook; Austria: Harald Dobnig, Gerd Finkenstedt, Guenter Hoefle, Klaus Klaushofer, Martin Pecherstorfer, Peter Peichl; Belgium: Jean Body, Steven Boonen, Jean-Pierre Devogelaer, Piet Geusens, Jean Kaufman; Brazil: João Brenol, Jussara Kochen, Rubem Lederman, Sebastiao Radominski, Vera Szejnfeld, Cristiano Zerbini; Canada: Jonathan Adachi, Jacques Brown, Denis Choquette, David Hanley, Robert Josse, David Kendler, Richard Kremer, Frederic Morin, Wojciech Olszynski, Alexandra Papaioannou, Chiu KinYuen; China: Baoying Chen, Shouqing Lin; Colombia: Nohemi Casas, Monique Chalem, Juan Jaller, Jose Molina; Finland: Hannu Aro, Jorma Heikkinen, Heikki Kröger, Lasse Mäkinen, Juha Saltevo, Jorma Salmi, Matti Välimäki; France: Claude-Laurent Benhamou, Pierre Delmas, Patrice Fardellone, Georges Werhya; Germany: Bruno Allolio, Dieter Felsenberg, Joachim Happ, Manfred Hartard, Johannes Hensen, Peter Kaps, Joern Kekow, Ruediger Moericke, Bernd Ortloff, Peter Schneider, Siegfried Wassenberg; Hong Kong: Ping Chung Leung; Hungary: Adam Balogh, Bela Gomor, Tibor Hidvégi, Laszlo Koranyi, Péter Lakatos, Gyula Poór, Zsolt Tulassay; Israel: Rivka Dresner Pollak, Varda Eshed, A. Joseph Foldes, Sophia Ish-Shalom, Iris Vered, Mordechai Weiss; Italy: Silvano Adami, Antonella Barone, Gerolamo Bianchi, Sandro Giannini, Giovanni Carlo Isaia, Giovanni Luisetto, Salvatore Minisola, Nicola Molea, Ranuccio Nuti, Sergio Ortolani, Mario Passeri, Alessandro Rubinacci, Bruno Seriolo, Luigi Sinigaglia; Korea (Republic of): Woong-Hwan Choi, Moo-II Kang, Ghi-Su Kim, Hye-Soon Kim, Yong-Ki Kim, Sung-Kil Lim, Ho-Young Son, Hyun-Koo Yoon; Mexico: Carlos Abud, Pedro Garcia, Salomon Jasqui, Luis Ochoa, Javier Orozco, Javier Santos; New Zealand: Ian Reid; Norway: Sigbjørn Elle, Johan Halse, Arne Høiseth, Hans Olav, Høivik Ingun Røed, Arne Skag, Jacob Stakkestad, Unni Syversen; Poland: Janusz Badurski, Edward Czerwinski, Roman Lorenc, Ewa Marcinowska-Suchowierska, Andrzej Sawicki, Jerzy Supronik; Russia: Eduard Ailamazyan, Lidiya Benevolenskaya, Alexander Dreval, Leonid Dvoretsky, Raisa Dyomina, Vadim Mazurov, Galina Melnichenko, Ashot Mkrtoumyan, Alexander Orlov-Morozov, Olga Ostroumova, Eduard Pikhlak, Tatiana Shemerovskaya, Nadezhda Shostak, Irina Skripnikova, Vera Smetnik, Evgenia Tsyrlina, Galina Usova, Alsu Zalevskaya, Irina Zazerskaya, Eugeny Zotkin; Sweden: Osten Ljunggren, Johan Lofgren, Mats Palmér, Maria Saaf, Martin Stenström; Switzerland: Paul Hasler, Olivier Lamy, Kurt Lippuner, Claude Merlin, René Rizzoli, Robert Theiler, Alan Tyndall, Daniel Uebelhart; Taiwan: Jung-Fu Chen, Po-Quang Chen, Lin-show Chin, Jawl-Shan Hwang, Tzay-Shing Yang, Mayuree Jirapinyo; Thailand: Mayuree Jirapinyo, Rojanasthien Sattaya, Sutin Sriussadaporn, Soontrapa Supasin, Nimit Taechakraichana, Kittisak Wilawan; United Kingdom: Hugh Donnachie, Richard Eastell, William Fraser, Alistair McLellan, David Reid; United States: John Abruzzo, Ronald Ackerman, Robert Adler, John Aloia, Charles Birbara, Barbara Bode, Henry Bone, Donald Brandon, Jane Cauley, Felicia Cosman, Daniel Dionne, Robert Downs, Jr., James Dreyfus, Victor Elinoff. Ronald Emkey, Joseph Fanciullo, Darrell Fiske, Palmieri Genaro, M. Gollapudi, Richard Gordon, James Hennessey, Paul Howard, Karen Johnson, Conrad Johnston, Risa Kagan, Shelly Kafka, Jeffrey Kaine, Terry Klein, William Koltun, Meryl Leboff, Bruce Levine, E. Michael Lewiecki, Cora Elizabeth Lewis, Angelo Licata, Michael Lillestol, Barry Lubin, Raymond Malamet, Antoinette Mangione, Velimir Matkovic, Daksha Mehta, Paul Miller, Sam Miller, Frederik T. Murphy, Susan Nattrass, David Podlecki, Christopher Recknor, Clifford Rosen, Daniel Rowe, Robert Rude, Thomas Schnitzer, Yvonne Sherrer, Stuart Silverman, Kenna Stephenson, Barbara Troupin, Joseph Tucci, Reina Villareal, Nelson Watts, Richard Weinstein, Robert Weinstein, Michael Weitz, Richard White. The study was funded by Novartis Pharma. Clinical trials number NCT00049829 and trial registration date 14/11/2002.

Editorial assistance for this manuscript was provided by Holly Gilbert-Jones of BioScience Communications, London, UK.

Footnotes

Disclosures

JC, DB, LP, ZM, and IR have received support for the submitted work. JC and IR have a relationship with Novartis; DB has relationships with Novartis, Merck, Roche, and Amgen; SB has relationships with Novartis, Merck, Roche-GlaxoSmithKline, Procter & Gamble, and Sanofi-Aventis; SC has consultancy relationships with Eli Lilly and Amgen and honoraria relationships with Eli Lilly and Novartis; PM is employed by Novartis; ZM has a relationship with Centro TIEMPO; PH has relationships with Novartis, Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Roche. The spouses, partners, or children of the authors have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work, and all the authors state that they have no financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work or other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burger H, Van Daele PL, Grashuis K, et al. Vertebral deformities and functional impairment in men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:152–157. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ettinger B, Black DM, Nevitt MC, et al. Contribution of vertebral deformities to chronic back pain and disability: the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:449–456. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman SL, Minshall ME, Shen W, Harper KD, Xie S. The relationship of health-related quality of life to prevalent and incident vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2611–2619. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200111)44:11<2611::aid-art441>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nevitt MC, Ettinger B, Black DM, et al. The association of radiographically detected vertebral fractures with back pain and function: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:793–800. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-10-199805150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman SL, Piziak VK, Chen P, Misurski DA, Wagman RB. Relationship of health related quality of life to prevalent and new or worsening back pain in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:2405–2409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magaziner J, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, et al. Recovery from hip fracture in eight areas of function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M498–M507. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.9.m498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonen S, Autier P, Barette M, Vanderschueren D, Lips P, Haentjens P. Functional outcome and quality of life following hip fracture in elderly women: a prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:87–94. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Olszynski WP, et al. The impact of incident vertebral and non-vertebral fractures on health related quality of life in postmenopausal women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2002;22:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nevitt MC, Thompson DE, Black DM, et al. Effect of alendronate on limited-activity days and bed-disability days caused by back pain in postmenopausal women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:77–85. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1729–1738. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hays J, Ockene JK, Brunner RL, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on health-related quality of life. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1839–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francis RM, Aspray TJ, Hide G, Sutcliffe AM, Wilkinson P. Back pain in osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:895–903. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genant HK, Halse J, Briney WG, Xie L, Glass EV, Krege JH. The effects of teriparatide on the incidence of back pain in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1027–1034. doi: 10.1185/030079905X49671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nevitt MC, Chen P, Dore RK, et al. Reduced risk of back pain following teriparatide treatment: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-2013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knopp JA, Diner BM, Blitz M, Lyritis GP, Rowe BH. Calcitonin for treating acute pain of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1281–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1798-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ofluoglu D, Akyuz G, Unay O, Kayhan O. The effect of calcitonin on beta-endorphin levels in postmenopausal osteoporotic patients with back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:44–49. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0228-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papadokostakis G, Damilakis J, Mantzouranis E, Katonis P, Hadjipavlou A. The effectiveness of calcitonin on chronic back pain and daily activities in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:356–362. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0916-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards B, Song J, Dunlop P, Fink H, Cauley JA. Functional decline after incident wrist fractures: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3324. [In press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]