Abstract

We examined 22 articles to compare Black Latinos/as’ with White Latinos/as’ health and highlight findings and limitations in the literature. We searched 1153 abstracts, from the earliest on record to those available in 2016. We organized the articles into domains grounded on a framework that incorporates the effects of race on Latinos/as’ health and well-being: health and well-being, immigration, psychosocial factors, and contextual factors.

Most studies in this area are limited by self-reported measures of health status, inconsistent use of race and skin color measures, and omission of a wider range of immigration-related and contextual factors.

We give recommendations for future research to explain the complexity in the Latino/a population regarding race, and we provide insight into Black Latinos/as experiences.

The Hispanic/Latino/Latina population is the largest minority group in the United States and is expanding rapidly; it is projected to make up 29% of the population by 2050.1 Latinos/as have higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity than do non-Latino/a White adults.2 In fact, cancer and heart disease are the leading cause of death among Latinos/as.2 Although Latinos/as generally have better mental health than do non-Latino/a Whites, Latinos/as are less likely to receive care because of lack of health insurance, socioeconomic status, and inadequate access to care.2,3 Therefore, barriers to health care place Latinos/as at greater risk for worsened mental health. Health disparities are conceptualized as both physical and mental health differences—which are closely linked with economic, social, and environmental disadvantage—and adversely affect Latinos/as because they systematically experience social and economic obstacles.4 Much of the literature, however, has studied Latinos/as as a homogenous group, glossing over the importance of race within the Latino/a health disparities context.5,6 This has contributed to Black Latinos/as being omitted from the health disparities discourse because they are thought to fare similarly to White Latinos/as. However, growing evidence suggests that Black and White Latinos/as differ in health-related outcomes.5–8

We recognize that some studies use the term “Hispanic” to refer to Spanish-speaking individuals with origins in Latin America and the Caribbean. For the sake of consistency, we will use mainly “Latinos/as.” The term “Black Latino/a” (or “Afro-Latino”) refers to a Latin American or Caribbean person of African ancestry who is brown or dark skinned. This individual identifies ethnically as Latino/a and identifies racially as Black or is perceived by others racially as Black.6,9 The number of Latinos/as who identify as Black has been rapidly increasing in the United States.10–12 In fact, the Black Latino/a population more than doubled from approximately 389 000 in 1980 to 940 000 in 2000 and comprised about 1.2 million of the Latino/a population in 2010.10,11

The burden of existing health disparities among Latinos/as may be more pervasive among Black Latinos/as because they may experience unique stressors owing to society’s unequal treatment of individuals on the basis of race.5,13 Racial categorization in the United States exposes individuals to opportunities and disadvantages that can influence their health outcomes.14 Although Black Latinos/as may share the cultural milieus (e.g., familism and religiosity) with their White Latino/a counterparts, the added experience of interpersonal- and contextual-level discrimination may contribute to health disparities among Black Latinos/as.6 Very little is known, however, about the role race plays in Latino/a health. We have provided a critical analysis of the literature on health disparities among Black Latinos/as, with the goal of highlighting the strengths and limitations of the current research.

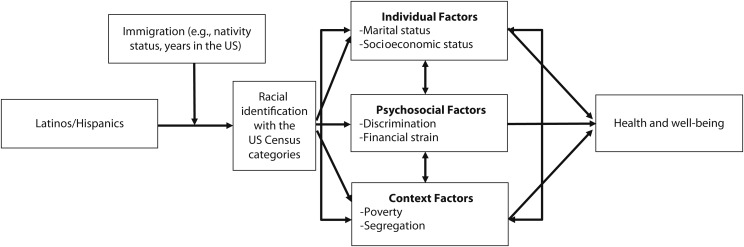

Borrell proposed a framework (Figure 1) to aid in understanding the effects of race on Latino/a’s health and well-being.6 The framework suggests that Latinos/as, despite not favoring US racial dichotomization, categorize themselves in the US Census on the basis of how they identify racially or how US society sees and identifies them.6,15 Racial identification may be influenced by one’s generation in the United States, nativity status, years living in the United States, acculturation level, and language preference.5,6,11 For example, Latinos/as who identify racially as Black in the US Census are less likely to be first-generation immigrants and speak a language other than English at home (which is a proxy for acculturation) than are Latinos/as who identify racially as White or some other race.11

FIGURE 1—

Borrell’s Framework for the Effect of Race on Latinos/as’ Health and Well-Being

Source. Borrell.6

On the basis of the racial categorization, Black Latinos/as may experience different advantages and disadvantages than do White Latinos/as in a race-conscious society such as the United States. The racial categorization channels certain Latino/a subgroups toward or away from opportunities that may influence their life chances and, in turn, their health outcomes.

The model specifically posits that opportunities and resources are filtered through the individual, psychosocial, and contextual levels.6 At the individual level, characteristics of the individual (e.g., knowledge, skills, and personal history) can influence their health status. For example, Black Latinos/as have lower median household income, higher unemployment, and a higher poverty rate than do White Latinos/as.11,16 These factors affect access to social and physical environmental resources that promote or obstruct health and well-being.

At the psychosocial level, Black Latinos/as may experience higher levels of psychosocial stressors, such as financial strain and racial discrimination, which can erode the individual’s health through psychological responses (e.g., negative emotions, depressive symptoms), physiological responses (e.g., cortisol level), and health behaviors (e.g., smoking). For example, greater perceived discrimination is consistently associated with greater stress, anxiety and depression, and worsened general health.17,18 Further, perceived discrimination has been associated with a variety of health risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, excess alcohol use, physical inactivity) linked to chronic diseases.17,19

Comparable with other socioecological models, individual and psychosocial characteristics interact with social structures, such as segregation and environmental exposures, to further influence one’s health and well-being.6 For example, the neighborhoods where Black Latinos/as reside have lower median incomes, a higher share of poor residents, and a lower share of homeowners than do those where White Latinos/as live.11 It is also possible that Black Latinos/as, especially those living in high non-Latino/Latina Black segregated communities, may not have culturally appropriate societal resources to buffer the effects of certain stressors.

Lastly, the framework follows a life course pattern of cumulative exposure to health risks. In particular, certain events may have a greater impact on well-being when they occur during specific developmental stages.20 For example, early childhood poverty is negatively associated with working memory in young adulthood and is mediated by greater allostatic load during childhood.21 Because approximately a quarter of Latino/a families live in poverty,22 Latinos/as are disproportionately burdened by insufficient access to quality, nutritious foods and by higher exposure to stress. This burden may be compounded for Black Latinos/as, who may experience more disadvantages than do White Latinos/as.

The literature on health inequities among Black Latinos is limited and does not provide sufficient detail to understand the Black Latino/a experience in the United States. Therefore, we reviewed and summarized the literature, highlight the limitations, and recommend areas for future research.

METHODS

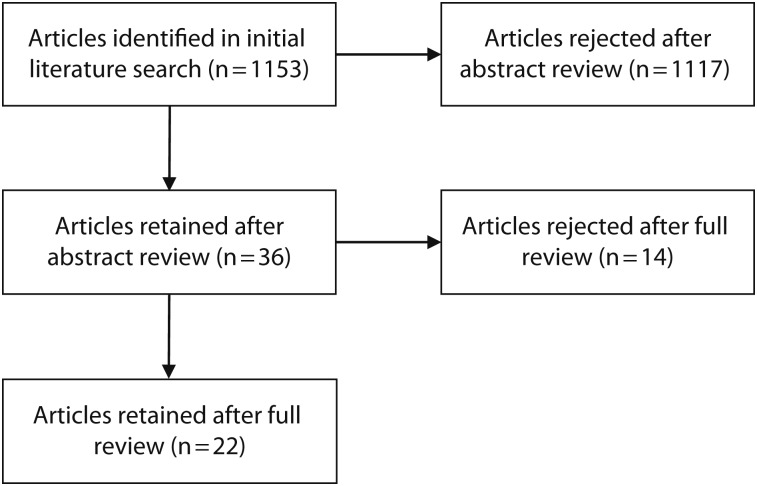

We conducted a search of 1153 abstracts in PubMed (177) and Web of Science (976), reviewing abstracts from the earliest on record to those available until 2016 using the following search terms: “Afro-Latino” (n = 15); “Black Hispanic” (n = 810); “Black Latino” (n = 141); “skin tone” and (“Hispanic OR Latino”; n = 33); and “skin color” and (“Hispanic OR Latino”; n = 148). We did not include any health terms so that we could capture all potentially relevant articles. We searched for articles in these databases with dates ranging from the databases’ starting dates to the present to capture all relevant articles. Figure 2 provides the exclusion and inclusion process from the search. We then manually skimmed each article to ensure that it pertained to mental health and health outcomes.

FIGURE 2—

Flowchart of the Article Selection Process

We included published research studies only if they were conducted in the United States, were available in English, and focused primarily on Black Latinos/as and health. We excluded review articles unless they were directly relevant to the themes that were part of our review. A research assistant examined the articles’ references and identified 3 additional articles. Of the 1153 citations, we identified 36 articles that met the search criteria. Of these 36 articles, we included 22 in this review and thoroughly evaluated them on the basis of Borrell’s model.6 We omitted 14 articles because either the study was conducted outside the United States or we considered it either a commentary or a theoretical article.

We organized the chosen articles by categories corresponding to domains in Borrell’s theoretical framework (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, provides an overview of the studies, including sample sizes and study design). We organized the articles into 4 categories: health and well-being, immigration, psychosocial factors, and contextual factors.

We included studies that investigated racial differences in the Latino/a population in regards to health status in the health and well-being category. We included studies that incorporated immigration-related factors (e.g., nativity status, generation status, years in the United States, or language preference) in their analyses in the immigration category. We included studies that focused on psychological stressors and social factors (e.g., social ties, perceived discrimination, and perceptions of control) in the psychosocial factor category. Lastly, we included studies that investigated the interplay between race, social structures (e.g., segregation, housing, environmental risks), and health in the contextual factors category.

Although Borrell’s framework proposed 2 additional domains (i.e., racial identification and individual characteristics), we believe they overlap considerably with the other domains, and, thus, we did not include them in the table. For example, studies often used racial identification (or skin color) as a potential predictor of health status difference. We placed these studies in the health and well-being category because the focus of the studies was to investigate racial differences in the Latino/a population in regards to health status. Studies used individual characteristics (e.g., socioeconomic status and gender) mainly as covariates in their analyses. Because these studies did not explicitly investigate the intersection between individual characteristics and race on health, we included them in 1 of the 4 domains that captured the essence of the study’s focus.

RESULTS

Our review of the literature on health disparities among Black Latinos/as revealed 22 articles. We organized the articles by categories corresponding to domains in Borrell’s theoretical framework to understand how the effects of race (or skin color) varied by those 4 factors (i.e., health and well-being, immigration, psychosocial factors, and contextual factors). Although many of these studies compared the health outcomes of other groups (e.g., African Americans and non-Latino/a Whites), we limited our summary to notable differences between Black Latinos/as and White Latinos/as.

Health and Well-Being

We found 13 articles that focused on physical health and mental health among Black Latinos/as. Much of the work focusing on physical health has been in the area of epidemiology, centering on racial and ethnic differences. Because of the relatively small sample size of Black Latinos/as in any particular year in national data sets, most of the studies had to combine data from multiple years to obtain adequate sample size. Data from the National Health Interview Survey and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, in particular, have been used to examine the extent of differences in physical health outcomes between Black Latinos/as and White Latinos/as.

Borrell used a sample of 944 Black Latinos/as (participants were identified as Black Hispanics) and 39 691 White Latinos/as from the National Health Interview Survey (1997–2005).23 She found that Black Latinos/as had a higher prevalence of self-reported hypertension than did White Latinos/as.23 Using different years (2000–2003) of the same survey, Borrell found that Black Latinos/as (n = 356) had greater odds of reporting fair or poor self-rated health than did White Latinos/as (n = 16 971).24

Similar findings were obtained using the 2003 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey (n = 241 038), with Black Latinos/as (n = 1110) having greater odds of reporting fair or poor self-rated health than did White Latinos/as (n = 10 077).25 Lastly, in a longitudinal study of non-Latino/Latina Black and Latino/a adolescents, Ramos et al. found that adolescent Black Latinas have higher levels of depressive symptoms than do their male counterparts and other Latinos/as. Black Latino males had higher levels of negative affect, a component of depressive symptoms, than did White Latino males.26

Immigration

Studies using immigration-related factors in their analyses (n = 4) suggest that the impact of colorism on mental health disparities for Black Latinos/as may be contingent on sociocultural factors, such as acculturation, country of origin, racial socialization, and ethnic identity.27,28 For example, Codina and Montalvo found that among 991 respondents of Mexican heritage, darker phenotype was significantly related to poorer mental health for US-born males, but phenotype was not related to mental health for US-born females or for Mexican-born males.28 Interestingly, darker phenotype was significantly related to better mental health for Mexican-born females. Additionally, generational status and darker skin were associated with greater levels of substance abuse among Mexican youths.27 Another study found that dark-skinned Puerto Rican women in the US are more likely to have low–birth weight infants.29

Psychosocial Factors

Four studies focused on psychosocial factors among Black Latinos. Garcia et al. used the 2011 Latino/Latina Decisions/impreMedia survey, which contained the data of 1200 Latinos/as (600 Latino/a registered voters and 600 nonregistered Latinos/as) to assess the impact of skin color, ascribed race, and discrimination experiences on self-rated health.30 They found that skin color and discrimination are independently associated with self-rated health status, in that, dark-skinned Latinos/as who have faced discrimination report worse health status than do lighter-skinned Latinos/as who have not faced discrimination in the past year. Nevertheless, they find that the 2 measures do not have an interactive effect on self-rated health. The authors did not report whether skin color and perceived discrimination were associated with one another or test whether perceived discrimination can serve as a mediator.

Another study by Ortiz and Telles used data from the Mexican American Study Project to examine the interplay between racial factors, education, and social interactions.31 Among the 758 Mexican American adults interviewed, those with darker skin reported more discrimination than did those with lighter skin; in particular, darker-skinned men reported more discrimination than did lighter-skinned men and women overall. Although their study did not focus on any specific health outcomes, their findings suggest that darker-skinned Latinos/as have higher exposure to discrimination than do lighter-skinned Latinos/as. Taken together, these results provide insight into the role psychosocial stress may play in health disparities among Black and White Latinos/as.

Contextual Factors

Only 1 study focused on the intersection of race and social structures among Latinos. Kershaw and Albrecht used Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data, combining years 2003 through 2008 to obtain a sample of 2263 Black Latinos/as and 31 960 White Latinos/as.7 This study found that among women, higher segregation was associated with a higher mean body mass index among White Latinos/as, but it was associated with a lower mean body mass index among Black Latinos/as.

In explaining these findings, Kershaw and Albrecht suggest that Black Latinos/as living in low Latino/a segregation areas are more likely to live in high non-Latino/a Black segregation areas, where there may be less healthy food options and access; conversely, White Latinos/as living in low Latino/a segregated areas were more likely to live in high non-Latino/a White segregated areas, where plenty of health-promoting social and physical environmental resources are available. Further, living in a predominantly Latino/a neighborhood may protect Black Latinos/as from the chronic stress of exposure to discrimination, which may negatively affect body mass index.

DISCUSSION

We located 22 articles focusing on health disparities among Black Latinos/as. We organized the articles into domains on the basis of Borrell’s theoretical framework: health and well-being, immigration, psychosocial factors, and contextual factors.6 Some articles did not cleanly fit into a particular domain, corroborating Borrell’s framework, which suggests that these domains are dynamic and often interact with one another to influence Black Latino/a’s health and well-being.6

The literature demonstrates that Black Latinos/as (and darker-skinned Latinos) have worse mental health and physical health outcomes than do White Latinos (and lighter-skinned Latinos/as). Furthermore, these studies revealed that health disparities between Black and White Latinos/as closely resemble those of non-Latino/a Blacks and non-Latino/a Whites.7,23,32,33 This is not surprising because Black Latinos/as have sociodemographic profiles that are similar to those of non-Latino/a Blacks, with a great proportion having lower income, higher rates of poverty, and lower rates of homeownership than do Whites.11,16,31

Studies that included immigration-related factors in their analyses revealed that skin color intersects with nativity status and generational status and affects the mental health outcomes of Black Latinos/as. Additionally, the studies we reviewed identified other factors that matter. Discrimination and neighborhood-level factors, such as segregation, may contribute to health differences between Black and White Latinos/as.7,31 On the basis of the literature, racial discrimination and segregation are not mutually exclusive to non-Latino/a Blacks; Black Latinos/as may also suffer from racial disadvantage in geography, opportunity, and access to resources.

Although the reviewed studies are a major contribution to the literature on Black Latinos/as, additional research is needed to better understand racial health disparities in the Latino/a population. The studies used mainly self-reported measures of health. Future studies might also use objective measures of health status, when possible, such as medical records and blood pressure readings, to accurately assess racial health disparities in the Latino/a population.

Researchers should investigate a wider range of social, psychological, physical, and chemical risk factors, preclinical indicators of disease (e.g., inflammation, coronary calcification, hemoglobin A1c [glycated hemoglobin]), specific health outcomes, global indicators of poor physiological functioning, and premature aging (e.g., allostatic load, telomere length, oxidative stress). Also unexplored is the extent to which Black Latinos/as’ disproportionate exposure to stressors may lead to certain behavioral and psychological patterns and responses that differ from those of White Latinos/as. To fully understand Black Latino/a health disparities, future studies should include a broad range of health indicators and outcomes to help elucidate the relationship between stress and disease. Lastly, the majority of the studies used cross-sectional data, which precludes causal inferences. Nevertheless, the studies highlight the importance of continual investigation in health disparities between Black and White Latinos/as.

Additional research is needed that specifically focuses on other immigration-related factors that affect the mental and physical health of Black Latinos/as. For example, the pressures of learning a new language and culture, referred to as acculturative stress, is associated with a reduction in health status.34 The pervasiveness and intensity of these stressors may be compounded for Black Latinos, who also experience societal and interpersonal racial discrimination in the United States. Future studies should examine how acculturative stress and discrimination may differentially affect the lived experience of Black Latino/a immigrants. Generational status and length of time in the United States will need to be considered as well because the experiences of young Black Latinos/as who have recently immigrated may differ from those who have been in the United States for longer periods of time. The immigration-related factors used in the reviewed studies were either generation status or place of residence.

Future studies should expand the concept of immigration status to other factors, such as age of immigration, country of origin, length of residence in the United States, language preference, and social affiliation. There is also great heterogeneity in the Latino/Latina population as it pertains to sociocultural and migration contexts. The circumstances of migration (e.g., country of origin’s economic instability vs family obligation) influence the application of Borrell’s model. For example, unplanned migration is associated with poorer physical health for Latina women.35

These contexts can influence other domains of Borrell’s model, such as age at immigration and financial situation. Therefore, Borrell’s model should be situated within the sociocultural, migration, and historical contexts of the Latino/a group. Relatedly, most of the reviewed studies focused on Latinos/as residing in California, which also limits our understanding to primarily Latinos of Mexican descent. Research should be expanded to include additional geographic areas where other Latino/a subgroups may reside (e.g., Miami, FL; Chicago, IL; and Houston, TX).

Skin color is shown to be a strong predictor of life chances and health. The inclusion of skin color measures in health disparities research is needed to gain a better understanding of how the social construction of race affects Latino/a health. Questions pertaining to color and phenotypic features may capture skin color privilege that standard race/ethnicity questions might not. Darker skin may not necessarily equate to Black Latino/a identity, particularly for those of Central and South America, who have strong native indigenous ancestry.

In fact, several studies have documented a higher percentage of black- and brown-skinned individuals among Caribbean Latinos/as owing to the greater mixture of African, Spaniard, and Taino in their ancestry than among South and Central American Latinos/as.36–37 Therefore, the meaning and effect of skin color would vary by the person’s country of origin as well as the person’s perception and attitude of race. Using multidimensional race response and multiracial categories (e.g., mestizo, mulatto, Afro-Latino)38 with skin color measures can improve our understanding of the sociocultural influence of race and skin color in relation to health outcomes.

Only 1 study investigated the interaction of social structures (i.e., segregation) and race among Latinos/as. This study did not have neighborhood-level information to identify the racial or ethnic composition of the neighborhoods where Black and White Latinos/as resided. Such information could provide further understanding of the differential residential opportunities available to Black and White Latinos/as living in low Latino/a segregation areas.7 Investigating other social structures that are social determinants of health, such as access to quality and affordable housing and environmental exposure (e.g., exposure to toxins), would expand our understanding of how contextual-level factors contribute to health disparities. Using national or large regional data sets that have individual-level factors (e.g., nativity status) can help us identify within-group differences in how Latinos/as navigate and use their social environment.

Conceptualizing “Black Latino/a” as its own unique ethnic/racial group poses a challenge for assessment and study design. Latino/a immigrants in general usually have to reconceptualize their racial identities when moving to the United States, a country that upholds a Black–White racial dichotomy.6,39 This may pose a problem for those whose self-identity and appearance is not in accordance with such a structure. Although standard race questions help capture the importance of race as a social determinant of health in the United States, the inclusion of more culturally relevant race questions can capture the health effects of their native countries’ social construction of race. Future studies should employ a new approach to measuring race questions in health research to help accurately capture Latinos/as who self-identify as Black Latinos/as (or Afro-Latinos/as).

Investigating the role of ascribed race—how others racially categorize an individual—in relation to Black Latino/a health can offer insight into Black Latino/a’s lived experience. Similar to skin color, ascribed race is able to capture differential advantages on the basis of race. For example, in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, self-identified Latinos/as who were socially assigned as White are more likely to report a better health status than are Latinos/as who were not socially assigned as being White.40 Yet, little is known about whether Latinos/as who are socially assigned as Black specifically have different health outcomes from those of Latinos/as who are socially assigned as White. Including this kind of measure (e.g., “How do other people usually classify you in this country?”) in future studies could help illuminate the multidimensionality of Latinos/as’ identity and its impact on Black Latino/a health.

Overall, there is an urgent need for additional research to understand the Black Latino/a experience. Black Latinos/as remain understudied in health disparities research, although recent studies indicate that Black Latinos/as suffer poorer health outcomes than do White Latinos/as. The lack of studies on Black Latinos/as may be related to conceptual and methodological challenges that appear in this area of research. To increase our understanding of the unique experiences of this understudied population, we need further investigation into immigration-related factors that contribute to health disparities for Black Latinos, expand health studies to more Latino/a subgroups, investigate the intersection of race and skin color, and explore a wider range of social structure factors and health outcomes.

Focusing on these areas, as well as on the conceptualization of “Black Latino/a,” will reveal potential racial differences in the Latino/a population. This effort will help us gain a better understanding of racial health disparities within the Latino/a population and help interventions develop targeted efforts to reduce health disparities within the Latino/Latina population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grant 3R25CA057711).

The authors thank Justin Rodgers for his help in preparing the article. The authors also thank the review committee for their suggestions, which improved the quality of the article.

Note. The article’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Passel JS, Cohn D. US population projections: 2005–2050. Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050. Accessed October 18, 2015.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Minority Health and Health Equity. CDC health disparities and inequalities report. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/CHDIReport.html. Accessed January 30, 2016.

- 3.Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R et al. Mental health care for Latinos: inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(12):1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healthy People. Disparities. 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities. Accessed May 26, 2016.

- 5.Araujo BY, Borrell LN. Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2006;28(2):245–266. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrell LN. Racial identity among Hispanics: implications for health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):379–381. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kershaw KN, Albrecht SS. Metropolitan-level ethnic residential segregation, racial identity, and body mass index among U.S. Hispanic adults: a multilevel cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaVeist-Ramos TA, Galarraga J, Thorpe RJ, Bell CN, Austin CJ. Are Black Hispanics Black or Hispanic? Exploring disparities at the intersection of race and ethnicity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(7):e21. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.103879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Álvarez López P. Afro-Latinos. In: Leonard DJ, Lugo-Lugo CR, editors. Latino History and Culture: An Encyclopedia. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference; 2015. pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humes K, Jones NA, Ramirez RR. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin, 2010. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logan JR. How race counts for Hispanic Americans. 2003. Available at: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED479962. Accessed January 30, 2016.

- 12.Nicholson SP, Pantoja AD, Segura GM. Race matters: Latino racial identities and political beliefs. 2005. Available at: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/39g3f25h. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- 13.Araujo Dawson B, Quiros L. The effects of racial socialization on the racial and ethnic identity development of Latinas. J Lat Psychol. 2014;2(4):200–213. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sternthal MJ, Slopen N, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health: how much does stress really matter? Du Bois Review. 2011;8(1):95–113. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavariega Monforti J, Sanchez GR. The politics of perception: an investigation of the presence and sources of perceptions of internal discrimination among Latinos. Soc Sci Q. 2010;91(1):245–265. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arce CH, Murguia E, Frisbie WP. Phenotype and life chances among Chicanos. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11(1):407–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borrell LN, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR et al. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, smoking and alcohol consumption in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Brondolo E. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):967–974. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans GW, Schamberg MA. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, and adult working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(16):6545–6549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811910106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macartney S, Bishaw A, Fontenot K. Poverty Rates for Selected Detailed Race and Hispanic Groups by State and Place: 2007–2011. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics, and Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borrell LN. Race, ethnicity, and self-reported hypertension: analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2005. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):313–319. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borrell LN, Dallo FJ. Self-rated health and race among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic adults. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(3):229–238. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borrell LN, Crawford ND. Race, ethnicity, and self-rated health status in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2006;28(3):387–403. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos B, Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V. Dual ethnicity and depressive symptoms: implications of being Black and Latino in the United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2003;25(2):147–173. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayers SL, Kulis S, Marsiglia FF. The impact of ethnoracial appearance on substance use in Mexican heritage adolescents in the Southwest United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2013;35(2):227–240. doi: 10.1177/0739986312467940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Codina GE, Montalvo FF. Chicano phenotype and depression. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1994;16(3):296–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landale NS, Oropesa RS. What does skin color have to do with infant health? An analysis of low birth weight among mainland and island Puerto Ricans. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(2):379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia JA, Sanchez GR, Sanchez-Youngman S, Vargas ED, Ybarra VD. Race as lived experience: the impact of multi-dimensional measures of race/ethnicity on the self-reported health status of Latinos. Du Bois Rev. 2015;12(2):349–373. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X15000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz V, Telles E. Racial identity and racial treatment of Mexican Americans. Race Soc Probl. 2012;4(1):41–56. doi: 10.1007/s12552-012-9064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bediako PT, BeLue R, Hillemeier MM. A comparison of birth outcomes among Black, Hispanic, and Black Hispanic women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(4):573–582. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0110-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borrell LN. Self-reported hypertension and race among Hispanics in the National Health Interview Survey. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alegria M, Woo M. Conceptual issues in Latino mental health. In: Villarruel F, editor. Handbook of U.S. Latino Psychology: Developmental and Community-Based Perspectives. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres JM, Wallace SP. Migration circumstances, psychological distress, and self-rated physical health for Latino immigrants in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1619–1627. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Araujo-Dawson B. Understanding the complexities of skin color, perceptions of race, and discrimination among Cubans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2015;37(2):243–256. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez CE. Changing Race: Latinos, the Census, and the History of Ethnicity in the United States. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2001. Latinos in the U.S. race structure; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amaro H, Zambrana RE. Criollo, mestizo, mulato, LatiNegro, indígena, White, or Black? The US Hispanic/Latino population and multiple responses in the 2000 census. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1724–1727. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itzigsohn J, Giorguli S, Vazquez O. Immigrant incorporation and racial identity: racial self-identification among Dominican immigrants. Ethn Racial Stud. 2005;28(1):50–78. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones CP, Truman BI, Elam-Evans LD et al. Using “socially assigned race” to probe White advantages in health status. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):496–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]