Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are well known to elicit a plethora of detrimental effects on cellular functions by causing damages to proteins, lipids and nucleic acids. Neurons are particularly vulnerable to ROS, and nearly all forms of neurodegenerative diseases are associated with oxidative stress. Here, we report the surprising finding that exposing C. elegans to low doses of H2O2 promotes, rather than compromises, sensory behavior and the function of sensory neurons such as ASH. This beneficial effect of H2O2 is mediated by an evolutionarily conserved peroxiredoxin-p38/MAPK signaling cascade. We further show that p38/MAPK signals to AKT and the TRPV channel OSM-9, a sensory channel in ASH neurons. AKT phosphorylates OSM-9, and such phosphorylation is required for H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function. Our results uncover a beneficial effect of ROS on neurons, revealing unexpected complexity of the action of oxidative stressors in the nervous system.

The deleterious role of reactive oxygen species has been widely reported in the nervous system. Here the authors report that surprisingly, low doses of H2O2 in fact enhances sensory neuron function and promotes sensory behaviors in C. elegans.

The deleterious role of reactive oxygen species has been widely reported in the nervous system. Here the authors report that surprisingly, low doses of H2O2 in fact enhances sensory neuron function and promotes sensory behaviors in C. elegans.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause a wide range of detrimental effects at the cellular level, leading to protein aggregation, aberrant cell signaling, and ultimately cell senescence and death1,2. They do so by oxidizing cellular components such as proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, as well as via cellular signaling1,3. Exposure to ROS also triggers defense mechanisms in the cell by up-regulating the production of antioxidants that remove ROS (ref. 2). An imbalance between ROS production and removal results in oxidative stress2. Neurons are among the cell types that are most vulnerable to oxidative insults, largely due to their high metabolic rate and low regenerative potential2,4. The deleterious role of ROS in the nervous system has been well documented. For example, the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, is associated with oxidative stress2,4. Ischemia, seizure, and traumatic brain injury all trigger excess production of ROS, which contribute to the brain damages caused by these pathophysiological conditions2,4.

Notwithstanding the detrimental impact of ROS, these agents are produced in cells under physiological conditions, such as mitochondrial respiration and innate immune response, and regulate cellular signaling3,5. For example, an increase in the production of ROS by mitochondria may induce adaptive responses and subsequently potentiate stress resistance in animals, a phenomenon called mitohormesis6,7. This led us to question if ROS have other types of effects on brain function.

Here, we explore this possibility in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, a popular genetic model organism with a nervous system that has been very well characterized. We find that while high concentrations of H2O2 are detrimental to C. elegans, low doses of H2O2, surprisingly, promote sensory behavior and also potentiate sensory neuronal function. Reducing the level of endogenous H2O2 produces an opposite effect, suggesting that the effect of H2O2 is physiological. The beneficial role of H2O2 is mediated by an evolutionarily-conserved peroxiredoxin-p38/MAPK signaling axis that signals to AKT and the sensory channel TRPV/OSM-9. We further show that AKT regulates TRPV/OSM-9 sensory channel through phosphorylation. These findings reveal a beneficial effect of ROS on nervous system function.

Results

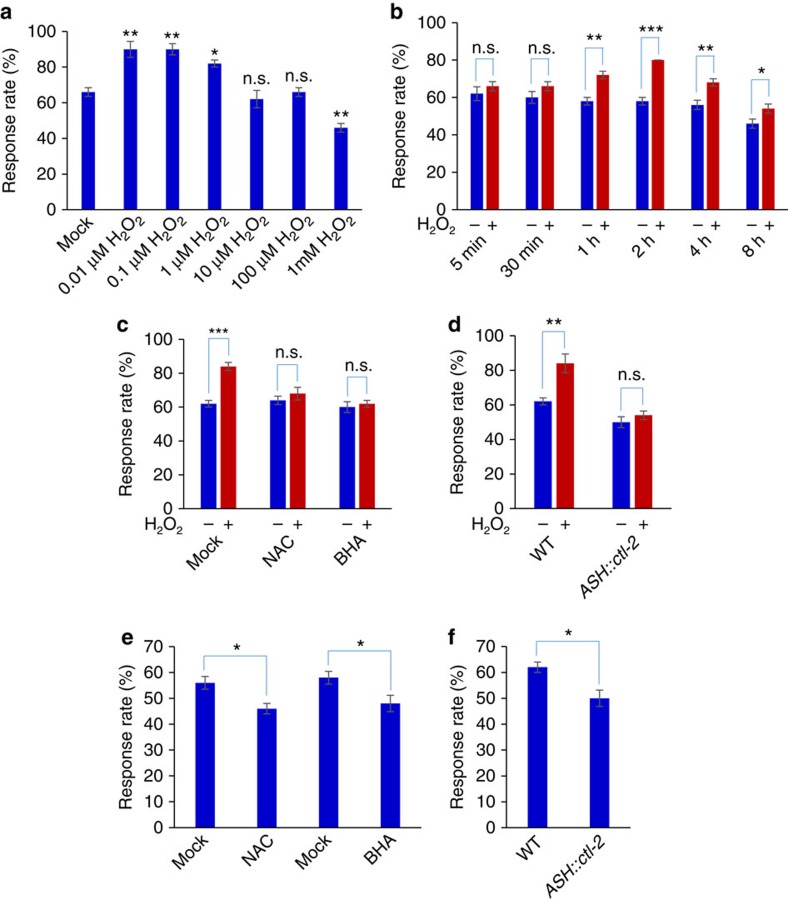

Low doses of H2O2 promote sensory behavior

Despite its small size, C. elegans nervous system drives a rich repertoire of behaviors, particularly sensory behaviors8. Previous work examining the role of ROS on worm behavior has mainly focused on high doses of H2O2, and found that exposing worms to the millimolar range of H2O2 severely compromises behavior9. We thus started by testing a wider range of concentrations of H2O2 (Fig. 1a). We incubated worms with varying concentrations of H2O2, and after a brief recovery, we examined their behavioral responses to sensory cues (see Materials and Methods). We focused on osmotic avoidance behavior, one of the best characterized sensory behaviors in C. elegans (ref. 8). Treating worms with 1 mM H2O2 suppressed osmotic avoidance behavior by decreasing their response rate to high osmolarity solution (glycerol) (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with the notion that oxidative insults negatively affect worm behavior9. Surprisingly, exposing worms to lower concentrations of H2O2 at the micromolar and sub-micromolar range potentiated osmotic avoidance behavior (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Treatment with H2O2 for 1 h was sufficient to induce such behavioral potentiation (Fig. 1b). Exposing worms to the ROS-producing agent paraquat also elicited similar effects (Supplementary Fig. 2a), while heat treatment did not (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Osmotic avoidance behavior is mediated by the polymodal sensory neuron ASH which detects high osmolarity cues10,11. This neuron also mediates octanol avoidance response12, and we obtained similar results with octanol avoidance behavior in worms treated with H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). These experiments reveal a beneficial role of H2O2 in promoting behavioral responses in C. elegans.

Figure 1. Low doses of H2O2 promote osmotic avoidance behavior.

(a) Low doses of H2O2 promote osmotic avoidance behavior while high concentrations of H2O2 inhibit it. Worms were pre-incubated with varying concentrations of H2O2 for 2 h. After a brief recovery on seeded NGM plates (up to 2 h), worms were tested for avoidance response to glycerol. To avoid a ceiling effect which would mask behavioral potentiation, a non-saturating concentration of glycerol (0.5 M) was used to challenge the worm. n≥20; *P<0.05, **P<0.005 (ANOVA with Dunnett's test); Error bars: s.e.m. (b) Exposing worms to H2O2 for one hour is sufficient to induce behavioral potentiation. Worms were pre-treated with 0.1 μM of H2O2 for varying durations of time. n≥20; *P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.0005 (t test); Error bars: s.e.m. (c) The antioxidants NAC and BHA block H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation. BHA (butylated hydroxyanisole, 25 μM) and NAC (N-acetyl-cysteine, 1 mM) were included during H2O2 (0.1 μM ) treatment. n≥10; ***P<0.0005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (d) Transgenic expression of the catalase gene ctl-2 in ASH neurons blocks H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation. H2O2: 0.1 μM. The sra-6 promoter was used to drive expression of ctl-2 in ASH neurons. n≥10; **P<0.005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (e) Reducing the level of endogenous H2O2 suppresses osmotic avoidance behavior. Worms were treated with BHA or NAC for 2 h, and right after the treatment, they were assayed for osmotic avoidance behavior. n≥10; *P<0.05 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (f) Reducing the level of endogenous H2O2 in ASH neurons suppresses osmotic avoidance behavior. Transgenic expression of the catalase gene ctl-2 in ASH neurons suppressed osmotic avoidance behavior. H2O2: 0.1 μM. n≥10; *P<0.05 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. Note: 0.1 μM H2O2 was used to induce potentiation of osmotic avoidance behavior and ASH neuron sensory response throughout the paper unless otherwise indicated.

To verify whether the observed potentiation of behavioral responses was caused by H2O2, we tested the effect of N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), two commonly used antioxidants13. Both antioxidants blocked H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation (Fig. 1c). To provide further evidence, we took a genetic approach by overexpressing catalase in worms. Catalase specifically removes H2O2 in the cell, antagonizing the action of H2O2 (ref. 14). Overexpression of the C. elegans catalase gene ctl-2 as a transgene in ASH neurons, which mediate osmosensation10,11, abolished the ability of H2O2 to induce behavioral potentiation (Fig. 1d). These results provide further evidence that H2O2 treatment can potentiate osmotic avoidance behavior.

Reducing endogenous H2O2 level suppresses sensory behavior

As H2O2 treatment can potentiate osmotic avoidance behavior, we wondered if reducing the H2O2 level suppresses this behavior. To test this, we treated worms with BHA and NAC, two commonly used H2O2 scavengers. To better evaluate the effect of BHA and NAC, we modified the protocol by assaying the behavior right after the treatment (see Methods). We found that BHA and NAC treatment suppressed osmotic avoidance behavior (Fig. 1e), suggesting that endogenous H2O2 may have a role in potentiating this sensory behavior. To interrogate the role of H2O2 in ASH neurons, we assayed worms overexpressing ctl-2 as a transgene specifically in ASH neurons, as catalase specifically removes H2O2. We found that this transgene suppressed osmotic avoidance behavior (Fig. 1f). These results provide further evidence supporting a role of H2O2 in promoting osmotic avoidance behavior.

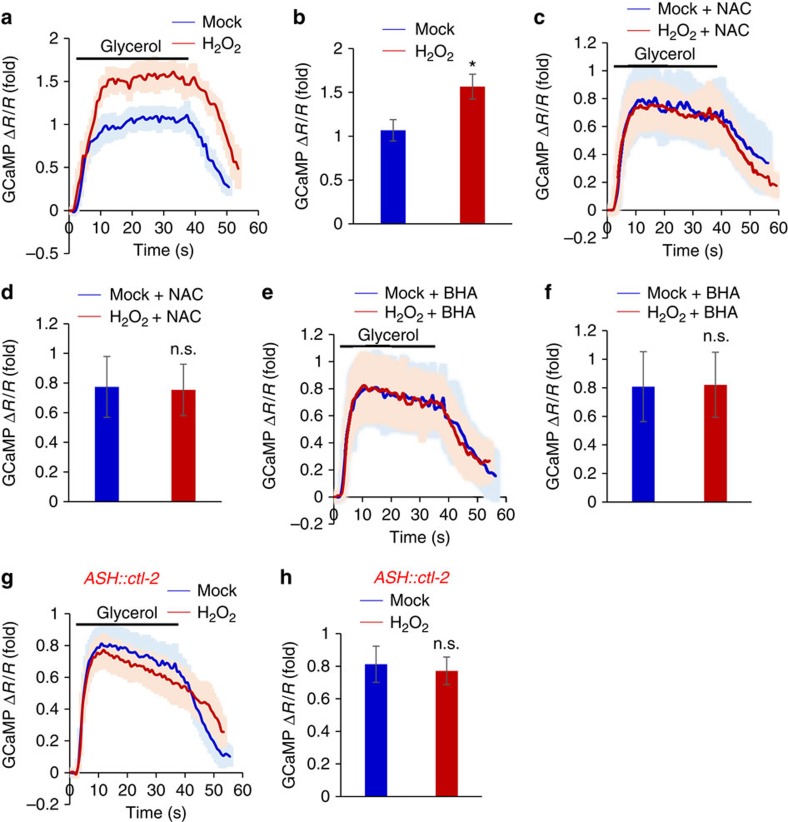

H2O2 promotes sensory neuron function

To investigate the neuronal mechanisms underlying H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation, we examined the function of ASH sensory neurons10,11. Calcium imaging experiments showed that H2O2 treatment potentiated the response of ASH neurons to high osmolarity solution (glycerol) (Fig. 2a,b). This potentiation effect was abolished by the antioxidants NAC and BHA (Fig. 2c–f), as well as by a transgene overexpressing the catalase gene ctl-2 in ASH neurons (Fig. 2g,h). These data indicate that exposure to H2O2 promoted ASH neuron function, providing a neuronal basis underlying H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation.

Figure 2. H2O2 treatment promotes ASH neuron function.

(a,b) H2O2 treatment potentiates the sensory response of ASH neurons. To enable ratiometric calcium imaging, GCaMP6 and mCherry were co-expressed in ASH neurons as a transgene using the sra-6 promoter. Worms were pre-treated with H2O2 (0.1 μM) for 2 h, and ASH neurons were recorded for their response to glycerol (0.5 M). Shades along the calcium traces in (a) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (b) summarizes the data in (a). n≥18; *P<0.05 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (c–f) The antioxidants NAC and BHA block H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response. NAC or BHA was included during H2O2 treatment. Calcium imaging of ASH neurons was performed as described in (a). Shades along the traces in (c) and (e) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (d) and (f) summarizes the data in (c) and (e), respectively. n≥8 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (g,h) Transgenic expression of the catalase gene ctl-2 blocks H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response. The sra-6 promoter was used to drive expression of ctl-2 in ASH neurons. Calcium imaging of ASH neurons was performed as described in (a). Shades along the traces in (g) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (h) summarizes the data in (g). n≥9 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m.

We also examined other types of sensory behaviors such as chemotaxis. Similarly, exposing worms to low doses of H2O2 potentiated their attractive behavioral responses to odors (that is diacetyl), indicating that H2O2 treatment promoted olfactory behavior (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The sensory activity of AWA olfactory neurons, which detect diacetyl15, was also potentiated by H2O2 treatment as shown by calcium imaging (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c). These results demonstrate that H2O2 exposure can promote both avoidance and attractive behaviors. For simplicity, we decided to focus on osmotic avoidance behavior for further characterizations.

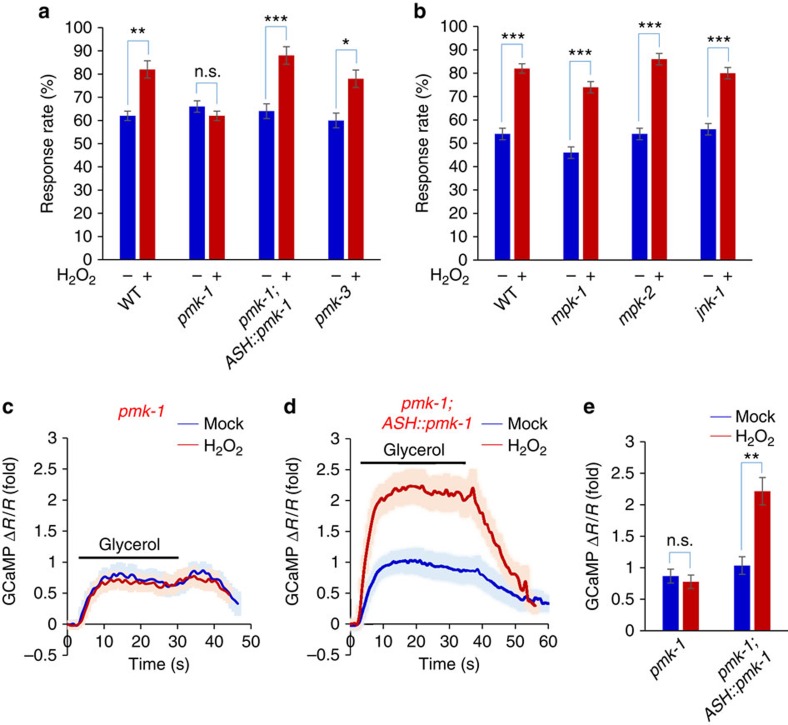

p38/MAPK signaling mediates the potentiation effect of H2O2

What are the molecular mechanisms underlying H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and neuronal function? H2O2 is known to stimulate MAPK signaling16,17. The C. elegans genome encodes all three major classes of MAPKs: ERK, JNK and p38 (refs 18, 19). We found that loss of the p38 gene pmk-1 abolished the ability of H2O2 to induce behavioral potentiation, while the closely related pmk-3 was not required (Fig. 3a). In addition, mutations in ERK (mpk-1 and mpk-2) and JNK (jnk-1) did not have a notable effect (Fig. 3b). This points to a specific role for pmk-1 in mediating H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation, consistent with a reported role of pmk-1 in oxidative stress signaling20. Expression of pmk-1 complementary DNA (cDNA) as a transgene in ASH neurons was sufficient to rescue the phenotype (Fig. 3a), indicating that PMK-1 acts in ASH neurons. We also examined the activity of ASH by calcium imaging, and found that H2O2 treatment can no longer promote ASH sensory activity in pmk-1 mutant worms (Fig. 3c–e), a defect that can be rescued by a transgene expressing pmk-1 cDNA in ASH neurons (Fig. 3c–e). Thus, the p38 ortholog PMK-1 is required for H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function.

Figure 3. H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function requires the p38/MAPK PMK-1.

(a) H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation requires PMK-1. In pmk-1(km25) but not pmk-3(ok169) mutant worms, H2O2 treatment failed to promote osmotic avoidance behavior. This defect was rescued by a transgene expressing pmk-1 cDNA in ASH neurons driven by the sra-6 promoter. n≥20; *P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.0005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (b) H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation does not require ERK (MPK-1 and MPK-2) or JNK (JNK-1). mpk-1(tm3476), mpk-2(tm3859) and jnk-1(gk7) mutant worms were tested. n≥10; ***P<0.0005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (c–e) H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response requires PMK-1. In pmk-1 mutant worms, H2O2 treatment can no longer promote ASH calcium response to glycerol stimulus (c). This defect was rescued by a transgene expressing pmk-1 cDNA in ASH neurons driven by the sra-6 promoter (d). Shades along the traces in (c) and (d) represent error bars (s.e.m.). (e) summarizes the data in (c) and (d). n≥9; **P<0.005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m.

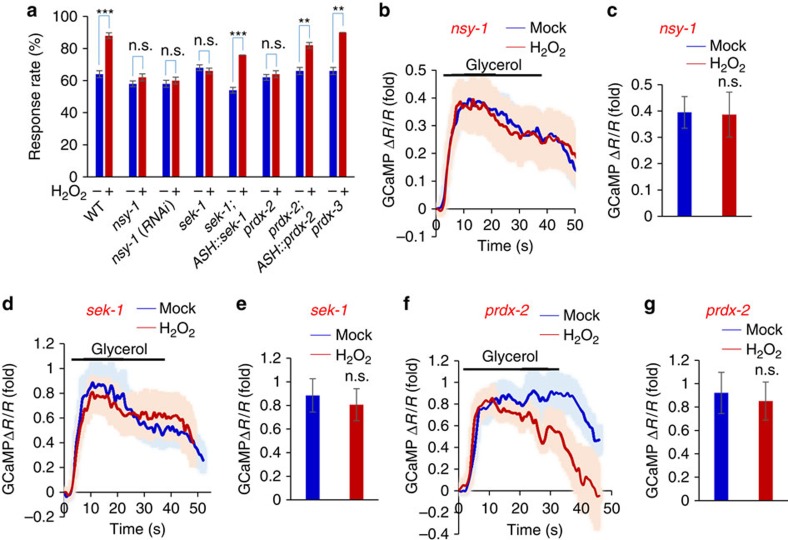

p38 is activated by a conserved MAPK signaling cascade that has been extensively characterized biochemically and genetically in diverse organisms17,18,19,21. In C. elegans, the ASK1/MAPKKK ortholog NSY-1 and MKK/MAPKK ortholog SEK-1 are known to be in the cascade to activate p38/PMK-1 (refs 18, 19, 22, 23). We thus tested NSY-1 and SEK-1. Loss of NSY-1 blocked the ability of H2O2 to induce behavioral potentiation (Fig. 4a). RNAi of nsy-1 gene in ASH neurons using a transgene in wild-type background also blunted H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation (Fig. 4a). Apparently, NSY-1 is required in ASH neurons to mediate behavioral potentiation. Similarly, H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation was also absent in sek-1 mutant worms (Fig. 4a), and this phenotype can be rescued by a transgene expressing sek-1 cDNA in ASH neurons (Fig. 4a), demonstrating a requirement for SEK-1 in ASH neurons. Further evidence came from calcium imaging experiments. In nsy-1 mutant worms, H2O2 treatment can no longer promote ASH sensory activity (Fig. 4b,c). RNAi of nsy-1 gene in ASH neurons using a transgene yielded a similar result (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b), suggesting that NSY-1 is required in ASH neurons to mediate neuronal potentiation. Similarly, we detected no potentiation of ASH sensory activity in sek-1 mutant worms (Fig. 4d,e), and this phenotype was rescued by a transgene expressing sek-1 cDNA in ASH neurons (Supplementary Fig. 4c,d). Thus, SEK-1 is also required for H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response. We conclude that the entire p38/MAPK signaling cascade is required for mediating H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function.

Figure 4. H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function requires peroxiredoxin-p38/PMK-1 signaling.

(a) H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation requires NSY-1/ASK1, SEK-1/MKK, and PRDX-2/peroxiredoxin. In nsy-1(ok593), sek-1(km4) and prdx-2(gk169) mutant worms, H2O2 treatment failed to promote osmotic avoidance behavior. RNAi of nsy-1 gene in ASH neurons of wild-type worms recapitulated the phenotype. This was done by expressing nsy-1 RNAi as a transgene in ASH neurons under the sra-6 promoter. The sek-1 and prdx-2 mutant phenotype was rescued by a transgene expressing sek-1 and prdx-2 cDNA in ASH neurons driven by the sra-6 promoter, respectively. n≥20; **P<0.005, ***P<0.0005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (b,c) H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response requires NSY-1. In nsy-1 mutant worms, H2O2 treatment can no longer promote ASH calcium response to glycerol stimulus (b). Shades along the traces in (b) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (c) summarizes the data in (b). n≥8; Error bars: s.e.m. (d,e) H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response requires SEK-1. In sek-1 mutant worms, H2O2 treatment can no longer promote ASH calcium response to glycerol stimulus (d). Shades along the traces in (d) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (e) summarizes the data in (d). n≥9; Error bars: s.e.m. (f,g) H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response requires PRDX-2. In prdx-2 mutant worms, H2O2 treatment can no longer promote ASH calcium response to glycerol stimulus (f). Shades along the traces in (f) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (g) summarizes the data in (f). n≥8; Error bars: s.e.m.

Role of peroxiredoxin in coupling H2O2 to p38/MAPK signaling

How is H2O2 coupled to p38/MAPK signaling? Peroxiredoxin (PRDX) came to our attention, as recent studies have unveiled an increasingly important role for these ‘antioxidants' in redox signaling24. In particular, 2-cys peroxiredoxin can serve as a ‘H2O2 receptor'24. In this case, H2O2 oxidizes a specific Cys residue in peroxiredoxin, leading to the formation of a peroxiredoxin homodimer through disulfide bonds24,25. Dimerized peroxiredoxin can then activate ASK1/MAPKKK in the p38/MAPK pathway25,26. Thus, peroxiredoxin can potentially act as a H2O2 sensor to functionally link H2O2 to p38/MAPK signaling. The worm genome encodes two 2-cys peroxiredoxin genes: prdx-2 and prdx-3, and prdx-2 has been suggested as a H2O2 sensor for lifespan regulation25. No defect was detected in prdx-3 mutant worms (Fig. 4a), indicating that prdx-3 is not required. By contrast, H2O2 treatment failed to induce behavioral potentiation in prdx-2 mutant worms (Fig. 4a). Transgenic expression of prdx-2 cDNA in ASH neurons rescued the mutant phenotype (Fig. 4a). Thus, PRDX-2 acts in ASH neurons to mediate H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation. In addition, calcium imaging of ASH neurons in prdx-2 mutant worms failed to detect H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory activity (Fig. 4f,g), and this defect can be rescued by a transgene expressing prdx-2 cDNA in ASH neurons (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f). These results identify PRDX-2/peroxiredoxin as a key molecule that couples H2O2 to p38/MAPK signaling.

AKT-1 acts downstream of p38/MAPK

Having identified a key role for the peroxiredoxin-p38/MAPK signaling pathway, we then wondered which genes act downstream of this signaling pathway to mediate H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function. In redox signaling, the transcription factor Nrf2 is well known to mediate oxidative stress signaling by turning on a host of antioxidant genes to combat oxidative insults27. Interestingly, p38/MAPK is known to activate Nrf2 through phosphorylation27,28. We thus examined the sole C. elegans Nrf2 ortholog SKN-1 (ref. 29). In skn-1 mutant worms, H2O2 lost the ability to induce behavioral potentiation (Supplementary Fig. 5a), while mutant worms lacking DAF-16/FOXO, a transcription factor also involved in oxidative stress signaling, still exhibited H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation (Supplementary Fig. 5f). This supports a role for SKN-1 in the pathway. We also found that H2O2 treatment up-regulated the expression of gst-4 and gcs-1 (Supplementary Fig. 5g,h), two well-characterized SKN-1 target genes30, suggesting that exposure to low doses of H2O2 was sufficient to trigger oxidative stress responses in worms. Much to our surprise, recording of ASH neurons by calcium imaging detected robust H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response in skn-1 mutant worms (Supplementary Fig. 5b–e). Apparently, SKN-1 is not required for H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH neuron function. These results can be explained by a requirement of SKN-1 in those cells that act downstream of the sensory neuron ASH in the neural circuitry to drive osmotic avoidance behavior, for example, interneurons, motor neurons and/or muscles.

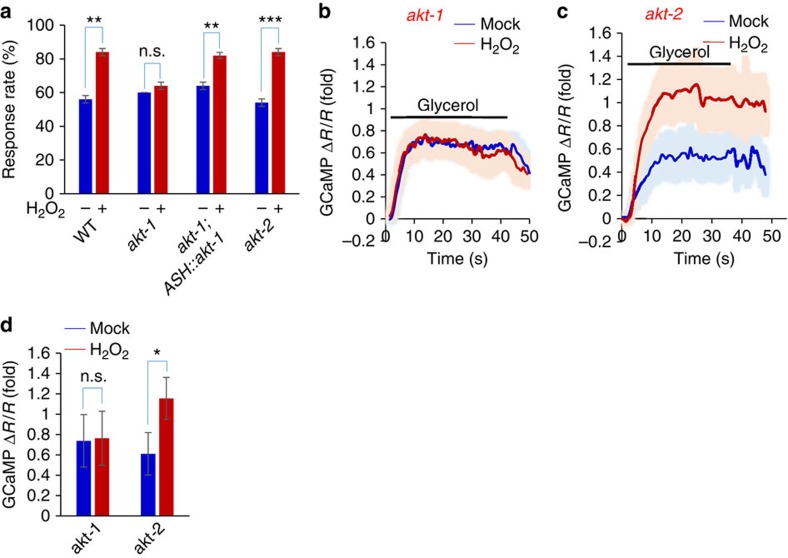

The lack of a critical role for Nrf2/SKN-1 in ASH neurons poses a challenge to unravel the signaling events downstream of p38/PMK-1. Clearly, p38/PMK-1 substrates other than Nrf2/SKN-1 are involved. We reasoned that those proteins critical for ASH sensory activity could be potential targets of p38/PMK-1. The TRPV channel OSM-9 thus came to our attention because it is the primary sensory channel in ASH neurons11,31,32. However, no putative p38 phosphorylation site is predicted in OSM-9. On the other hand, five putative AKT phosphorylation sites are found in OSM-9 (see below). As it has been well established that p38/MAPK can activate AKT through a kinase complex33, we explored a potential involvement of AKT in mediating H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation. Two akt genes are encoded by the C. elegans genome: akt-1 and akt-2. AKT-2 does not appear to be involved, as H2O2 treatment can still induce behavioral potentiation in akt-2 mutant worms (Fig. 5a). By contrast, H2O2 treatment failed to do so in akt-1 mutant animals (Fig. 5a). Transgenic expression of akt-1 cDNA in ASH neurons rescued the mutant phenotype (Fig. 5a), uncovering a key role for AKT-1 in mediating H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation. Calcium imaging of ASH neurons in akt-1 mutant worms also revealed a severe defect in H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response (Fig. 5b–d), and this phenotype can be rescued by a transgene expressing akt-1 cDNA in ASH neurons (Supplementary Fig. 4g,h). These data identify an important role for AKT-1 in the pathway.

Figure 5. H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function requires AKT-1.

(a) H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation requires AKT-1 but not AKT-2. In akt-1(mg306) but not akt-2(ok391) mutant worms, H2O2 treatment failed to promote osmotic avoidance behavior. This phenotype was rescued by a transgene expressing akt-1 cDNA in ASH neurons driven by the sra-6 promoter. n≥20; **P<0.005, ***P<0.0005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (b–d) H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response requires AKT-1 but not AKT-2. In akt-1 mutant worms, H2O2 treatment can no longer promote ASH calcium response to glycerol stimulus (b). No such defect was detected in akt-2(k391) mutant worms. Shades along the traces in (b) and (c) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (d) summarizes the data in (b) and (c). n≥9; Error bars: s.e.m. *P<0.05 (ANOVA).

Taken altogether, our data suggest that PDRX-2, MAPK pathway and AKT-1 form a signaling cascade to mediate the beneficial effect of H2O2. Though the upstream-downstream relationship between these molecules has been very well characterized biochemically in diverse organisms, we sought to gather some genetic evidence to further confirm such relationship through epistatic analysis. To do so, it is important to have both gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutant alleles. Two genes in this signaling cascade have both types of alleles available: nsy-1/MAPKKK and akt-1/AKT34,35. Worms carrying gain-of-function alleles of nsy-1 or akt-1 showed enhanced responses to high osmolarity solution (Supplementary Fig. 6a), consistent with a role for these two genes in promoting osmotic avoidance behavior. As reducing the level of endogenous H2O2 by a transgene overexpressing the catalase CTL-2 inhibited osmotic avoidance behavior (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 6a), we tested whether nsy-1 and akt-1 gain-of-function alleles can suppress this inhibitory effect, and found that they did (Supplementary Fig. 6a). This is consistent with the view that MAPK pathway and AKT act downstream of H2O2. We also found that akt-1 loss-of-function mutation suppressed the phenotype of nsy-1 gain-of-function mutant worms (Supplementary Fig. 6b), and vice versa (Supplementary Fig. 6c), consistent with the notion that AKT acts downstream of MAPK pathway. These epistatic analyses lend support to our model.

The detrimental effect of H2O2 does not require PMK-1 or AKT-1

As treating worms with high concentrations of H2O2 (for example 1 mM) suppressed osmotic avoidance behavior (Fig. 1a), we wondered if this detrimental effect of H2O2 is also mediated by the same signaling cascade. Interestingly, while H2O2-induced suppression of osmotic avoidance behavior still required the ‘H2O2 receptor' PRDX-2, it did not depend on MAPK/PMK-1 (Supplementary Fig. 7a); nor did it rely on AKT-1 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Calcium imaging of ASH neurons yielded similar results (Supplementary Fig. 7b–i). We thus suggest that the beneficial and detrimental effects of H2O2 are likely to be mediated by different signaling pathways.

A key role of the putative AKT site Thr10 in OSM-9

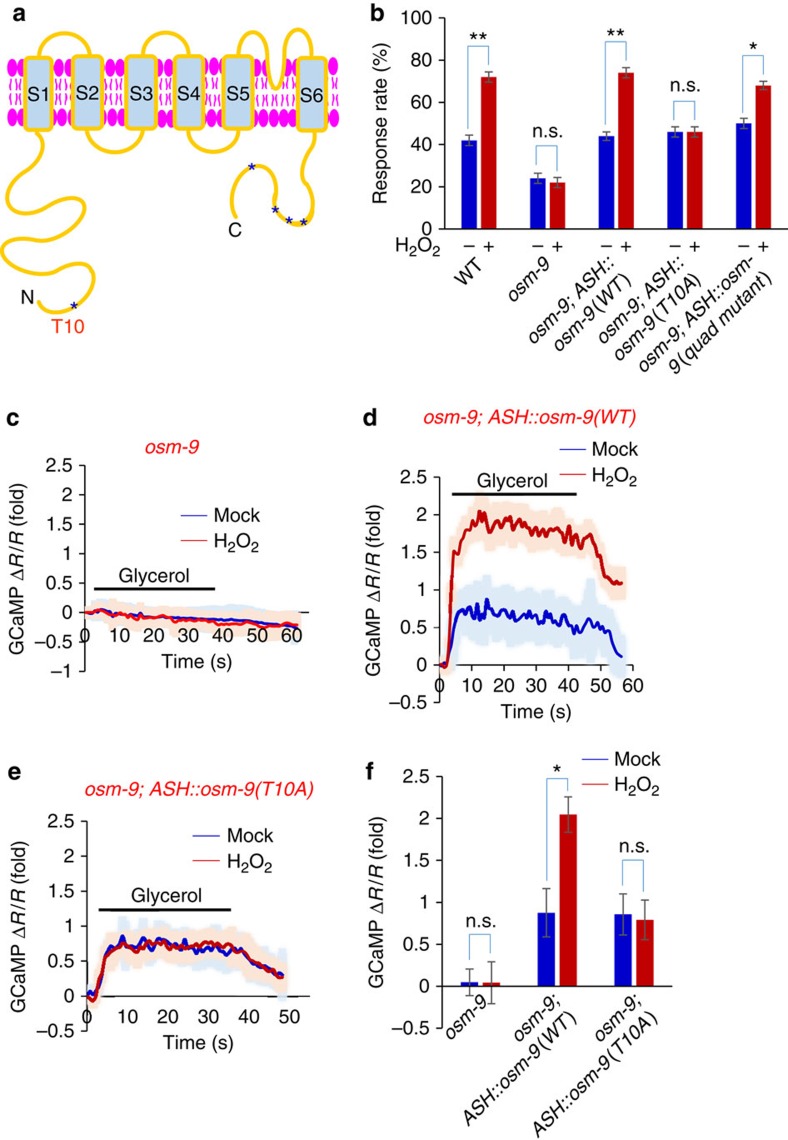

As OSM-9 is predicted to possess five putative AKT phosphorylation sites and it is also the primary sensory channel in ASH neurons, we hypothesize that OSM-9 may be a downstream target of AKT. To test this idea, we asked whether any of those putative AKT phosphorylation sites in OSM-9 is critical for H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation (Fig. 6a). Among the five putative AKT sites, one is located at the N-terminal end of OSM-9 while the other four are found at the C-terminus (Fig. 6a). We mutated all four C-terminal AKT sites in osm-9 cDNA from S/T to A, and introduced this ‘quad mutant' as a transgene in ASH neurons in the osm-9 mutant background. As reported previously11,31, osm-9 mutant worms did not respond to high osmolarity stimulus (Fig. 6b) (note: the basal response rate in the mutant arose from stimulus-independent spontaneous reversal events). As was the case with osm-9 wild-type transgene, osm-9(quad mutant) transgene expressed in ASH neurons can rescue osmotic avoidance behavioral response in naive worms, as well as behavioral potentiation in H2O2-treated worms (Fig. 6b). We conclude that the four putative AKT sites at the C-terminal end of OSM-9 are not required for H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation.

Figure 6. The putative AKT phosphorylation site T10 in OSM-9 is required for H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH function.

(a) Schematic of OSM-9 domain organization. Both the N and C-terminal fragments of OSM-9 are located intracellularly. Asterisks denote the putative AKT phosphorylation sites, with one at the N-terminus (T10) and the other four at the C-terminus (T769, T771, T787 and S839). These sites are predicted by Scansite. The N-terminal point mutation T10A is indicated. (b) The putative AKT phosphorylation site T10 in OSM-9 is required for H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation. osm-9(ky10) mutants failed to respond to glycerol stimulus. The basal response rate in the mutant arose from spontaneous reversal events that are present in the absence of glycerol stimulation. Wild-type and mutant forms of OSM-9 were expressed as transgenes in ASH neurons under the sra-6 promoter. Wild-type osm-9 transgene (ASH::osm-9), as well as osm-9 transgene with all the four putative C-terminal AKT sites mutated (that is ASH::osm-9(quad mutant)) rescued both the basal and H2O2-induced potentiation of osmotic avoidance response. However, osm-9 transgene harboring the point mutation T10A (that is ASH::osm-9(T10A)) failed to rescue H2O2-induced potentiation of osmotic avoidance response, though it rescued the basal avoidance behavior. n≥10; *P<0.05, **P<0.005 (ANOVA); Error bars: s.e.m. (c–f) The putative AKT phosphorylation site T10 in OSM-9 is required for H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response. In osm-9 mutant worms, ASH neurons did not respond to glycerol (c), and this defect was rescued by wild-type osm-9 transgene (d). Wild-type osm-9 transgene also rescued H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response (d). However, osm-9 transgene with the point mutation T10A (that is ASH::osm-9(T10A)) did not rescue H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response, though it rescued the basal glycerol sensory response in ASH neurons(e). Shades along the traces in (c–e) represent error bars (s.e.m.). Bar graph in (f) summarizes the data in (c–e). n≥8; Error bars: s.e.m. *P<0.05 (ANOVA).

We then turned our attention to the putative AKT site at the N-terminus of OSM-9. We generated a transgene osm-9(T10A) harboring a point mutation with this site changed to A (Fig. 6a). As was the case with wild-type osm-9 transgene, expression of osm-9(T10A) transgene in ASH neurons of osm-9 mutant worms rescued the basal osmotic behavioral response (Fig. 6b). This shows that the basic function of OSM-9 was not compromised by T10A mutation. However, this osm-9(T10A) transgene failed to rescue H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation (Fig. 6b), revealing a requirement for the putative phosphorylation site T10 in mediating H2O2-induced behavioral potentiation.

To gather functional evidence, we conducted calcium imaging experiments. Similar to wild-type osm-9 transgene (Fig. 6c,d), osm-9(T10A) transgene also rescued the basal ASH sensory response in osm-9 mutant worms (Fig. 6e,f), supporting the notion that the basic function of OSM-9 was not compromised by T10A mutation. However, this osm-9(T10A) transgene failed to rescue H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response (Fig. 6e,f). By contrast, osm-9(quad mutant) transgene, in which all four C-terminal AKT sites were mutated, rescued H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response (Supplementary Fig. 8). This set of experiments uncovers a specific role for the putative AKT phosphorylation site T10 in OSM-9 in mediating H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function.

To provide additional evidence, we recorded OSM-9-mediated sensory current by patch-clamp. Perfusion of glycerol-containing high osmolarity solution evoked an inward current in ASH neurons (Supplementary Fig. 9a,b). H2O2 treatment potentiated this current (Supplementary Fig. 9a,b), which is consistent with our behavioral and calcium imaging data. Using the same strategy as behavioral analysis and calcium imaging, we introduced transgenes expressing osm-9 cDNA in ASH neurons in osm-9 mutant background. Wild-type osm-9 transgene retained the ability to mediate H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory current (Supplementary Fig. 9c,d). By contrast, the osm-9(T10A) transgene, which encompasses a point mutation disrupting the putative AKT phosphorylation site, lost the ability to mediate H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory current (Supplementary Fig. 9e,f). This patch-clamp data presents additional evidence supporting a key role for the putative AKT site T10 in OSM-9 in mediating H2O2-induced potentiation of ASH sensory response.

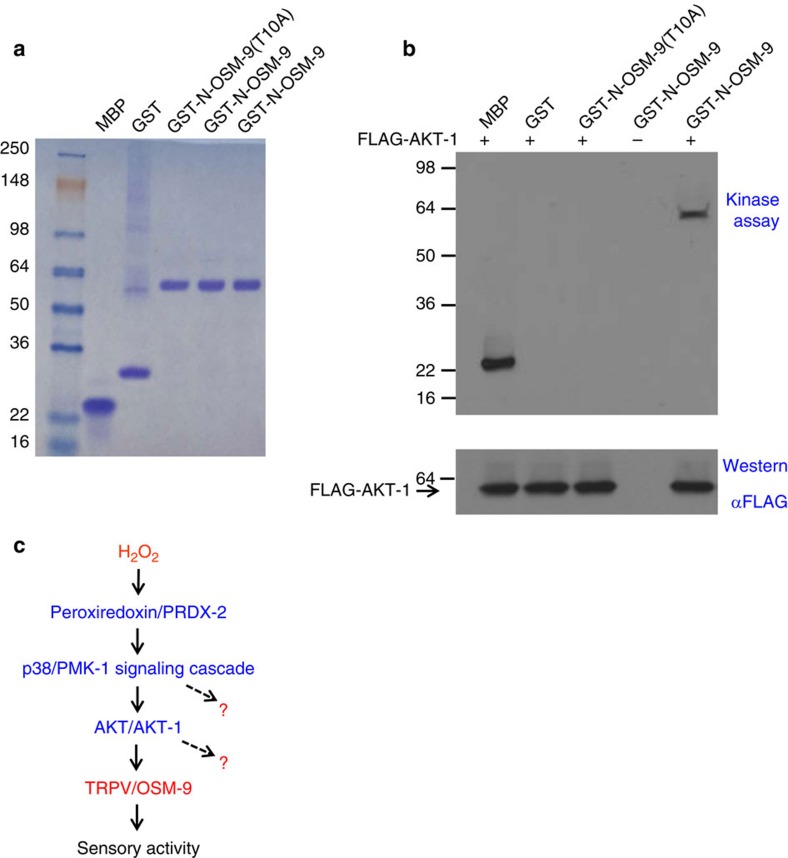

AKT-1 phosphorylates OSM-9 at Thr10 in vitro

The above data raised the intriguing possibility that the TRPV channel OSM-9 may be a substrate for AKT-1 kinase. To test this model, we performed an in vitro kinase assay. We produced the N-terminal fragment of OSM-9 as a GST fusion protein (that is GST-N-OSM-9) and purified it from bacteria lysate (Fig. 7a). The pan-kinase substrate MBP served as a positive control (Fig. 7a,b). Notably, AKT-1 transfected in HEK293 cells can phosphorylate GST-N-OSM-9 but not GST alone or GST-N-OSM-9(T10A) that harbors the point mutation T10A (Fig. 7b). Thus, AKT-1 can phosphorylate OSM-9 in vitro, identifying OSM-9 as a substrate for AKT-1.

Figure 7. AKT-1 phosphorylates OSM-9 in vitro.

(a) In vitro production of GST fusion proteins of OSM-9. The N-terminal fragment of wild-type and point mutant (T10A) of OSM-9 was fused to GST, expressed and purified from bacterial strain BL21. Shown is a SDS-PAGE gel stained by Coomassie blue. The pan-kinase substrate MBP and GST alone were also shown. (b) AKT-1 phosphorylates OSM-9 in an in vitro kinase assay. FLAG-tagged AKT-1 was transfected in HEK293T cells. After pull-down by anti-FLAG affinity beads, AKT-1 was tested for its ability to phosphorylate purified MBP, GST, and GST fusion proteins using (γ-32P)ATP as the substrate. Top panel: autoradiograph. Bottom panel: Western blot showing the amount of AKT-1 used in each experiment. (c) A schematic model illustrating the signaling pathway that mediates H2O2-induced potentiation of neuronal activity. Question marks indicate that additional substrates may exist.

Discussion

Owing to their deleterious effects on cellular functions, ROS have been implicated in a large variety of human diseases particularly neurodegenerative diseases2,4. In the current study, we demonstrate that unlike the commonly observed adverse effects of ROS, low doses of H2O2 can in fact promote sensory behavior and potentiate sensory neuron function in C. elegans, revealing a beneficial role of ROS in the nervous system. We also show that reducing the level of endogenous H2O2 compromises sensory behavior, suggesting that the role of H2O2 in promoting neuronal function is physiological. Such an effect of ROS may benefit the survival of C. elegans. For example, ROS are often associated with harsh environments. Sensitization of sensory neurons, such as the polymodal neuron ASH, by ROS would render the animals more responsive to noxious cues and thereby facilitate their escape from harsh environments. Meanwhile, as ROS can also promote the activity of chemosensory neurons such as AWA that detects food sources, this effect may also help the animals to approach pleasant environments.

Our results point to a model in which H2O2 promotes sensory behavior and ASH neuron function through a peroxiredoxin-p38/MAPK signaling axis (Fig. 7c). In this model, we propose that peroxiredoxin acts as a H2O2 sensor that transduces information through p38/MAPK signaling which in turn signals to AKT and the sensory channel OSM-9/TRPV in ASH neurons (Fig. 7c), and that AKT regulates the OSM-9/TRPV sensory channel by phosphorylating its N-terminus. As all the members in the peroxiredoxin-p38/MAPK signaling pathway are evolutionarily conserved across phylogeny, our results raise the intriguing possibility that H2O2 may play a similar role in regulating brain function in other organisms.

In addition to their role in the brain, ROS have been proposed to underlie cellular senescence of other cell types and affect organismal aging36. Interestingly, recent studies in C. elegans show that accumulation of ROS is not causal in the aging process and a mild increase in ROS production in mitochondria of ASI diet-sensitive neurons may even prolong lifespan through mitohormesis6,7,36,37. Though the underlying mechanisms are not well understood, p38/PMK-1 and SKN-1/Nrf2 are found to be involved20,37,38. This reveals a common role of p38/PMK-1 in mediating both ROS-mediated extension of lifespan and potentiation of neuronal function. Nevertheless, the signaling events downstream of p38/PMK-1 appear to be different in these two processes.

High doses of H2O2 compromise sensory behavior and sensory neuron function. One possibility is that this deleterious effect of H2O2 may result from its non-specific modification of proteins, nucleic acids and lipids. Interestingly, we find that this effect can also be blocked by loss of PRDX-2, indicating that it involves specific genes. On the other hand, mutations in p38/PMK-1 and AKT-1 cannot block this detrimental effect. Thus, other signaling pathways are probably also involved. We suggest that under low concentrations, ROS may primarily function as signaling molecules regulating specific cellular pathways, the outcome of which could be beneficial, while under high doses, ROS would become harmful by acting as signaling molecules and also by non-specifically modifying proteins, lipids and nucleic acids.

We identify the TRPV channel OSM-9 as a critical substrate for the peroxidoxin-p38/MAPK signaling pathway in ASH sensory neurons. Some TRP channels such as TRPA, TRPV and TRPC channels can be directly regulated by ROS through oxidation39. We thus do not rule out the possibility that OSM-9 may also be regulated by this mechanism. It should be noted that OSM-9 is probably not the only target of the peroxidoxin-p38/MAPK signaling pathway in ASH neurons. In other words, this signaling cascade may impinge on additional substrates in ASH, but the identities of which remain to be identified (Fig. 7c). These additional substrates may contribute to H2O2-induced potentiation of sensory behavior and ASH neuron function. It is also possible that peroxiredoxin-p38/MAPK signaling may recruit different sets of substrates in different classes of neurons. Lastly, we do not rule out the possibility that pathways other than peroxiredoxin-p38/MAPK may contribute to the observed beneficial effect of H2O2. Future effort is needed to address these intriguing questions. The current study unveils unexpected complexity of the action of ROS in the nervous system, providing an entry point to understanding the multifaceted roles of ROS in health and disease.

Methods

Strains

Behavioral assays

Osmotic avoidance behavior was carried out at 20 °C using a drop test assay as described previously40,41. Day 1 adult hermaphrodites were tested. We placed a small drop of glycerol-containing solution (M9) in the path of a worm moving forward. A positive response was scored if the worm stopped forward movement and also initiated a reversal that lasted at least half a head swing. The assay was conducted on NGM plates without bacteria. To avoid a ceiling effect that would mask behavioral potentiation, we used a non-saturating concentration of glycerol (for example 0.25–0.5 M) unless otherwise specified. Each worm was tested five times and a response rate was calculated for each animal. In general, 10–20 worms were assayed for each experiment (n number=10–20 worms), which should be sufficient based on power analysis. Chemotaxis assay was performed using the standard protocol described previously15. To avoid a ceiling effect, we used a non-saturating concentration of diacetyl (50,000 dilution) unless otherwise indicated.

To treat worms with H2O2, we incubated them with varying concentrations of H2O2 diluted in M9 buffer for 2 h. Fresh OP50 bacteria were included in M9 buffer to prevent starvation during H2O2 treatment. After treatment, worms were allowed to recover on seeded NGM plates for up to 2 h before behavioral, imaging and patch-clamp analysis. Mock-treated worms were used as a control. We also tested untreated worms (left on seeded NGM plates for 2 h) and found no difference from mock-treated worms (Supplementary Fig. 1). To test whether reducing the level of endogenous H2O2 would affect osmotic avoidance behavior, we treated worms with BHA or NAC for 2 h (OP50 included) and then assayed worms right after the treatment, since recovering worms on NGM plates would allow BHA and NAC to diffuse out, which would presumably lead to a rebound in H2O2 level inside the cell. 0.1 μM H2O2 was used to induce potentiation of osmotic avoidance behavior and ASH neuron sensory response throughout the paper unless otherwise indicated.

Calcium imaging

A microfluidic system was used to perform calcium imaging on Day 1 adult worms42. Worms were loaded onto a microfluidic chip mounted on an upright microscope (Olympus BX51WI), and incubated in standard bath solution (in mM): 145 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 20 glucose and 5 HEPES (320 mOsm; pH adjusted to 7.3). The images were acquired with a Roper Coolsnap CCD camera and analysed with MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices, Inc.). GCaMP6 and DsRed were co-expressed as a transgene in ASH under the sra-6 promoter to enable ratiometric imaging using blue and red light43,44,45. As ASH neurons are photosensitive46, we first exposed them to blue light for 2 min to bleach their intrinsic photosensitivity before applying chemical stimuli. The peak fold change in the ratio of G-CaMP/DsRed fluorescence was analysed. Each worm was only imaged once.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell recordings were performed on an upright microscope (BX51WI) with an EPC-10 amplifier45,47,48. Worms were glued and dissected on a sylgard-coated coverglass to expose ASH neurons. Bath solution (in mM): 145 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 20 glucose and 5 HEPES (320 mOsm; pH adjusted to 7.3). Pipette solution: 115 K-gluconate, 15 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.25 CaCl2, 20 sucrose, 5 BAPTA, 5 Na2ATP and 0.5 NaGTP (315 mOsm; pH adjusted to 7.2). DsRed and YFP fluorescence markers were expressed as a transgene (xuEx631) to label and identify ASH neurons for recording. Clamping voltage: −60 mV. Series resistance and membrane capacitance were both compensated during recording.

Biochemistry

GST fusion proteins were expressed and purified from BL21 bacteria using the standard protocol49. Briefly, after IPTG induction (1 mM, 5 h), bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in TEN buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.4% NP-40 and 1 mM DTT), and lysed by sonication. GST fusions were then purified using glutathione beads. To prepare for kinase assay, worm FLAG AKT-1 was cloned into pcDNA3 vector and transfected into HEK293T cells. Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (100 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 130 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM NaF and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). FLAG-AKT-1 was then pulled down by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG affinity beads. In vitro kinase assay was performed by incubating GST fusion proteins and FLAG-AKT-1-bound affinity beads in 50 μl kinase buffer (50 mM MOPS pH 7.2, 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM b-glycerolphosphate, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM NaCl and 100 uM ATP). 5 μCi of (γ32P)ATP and lipid activator mix (Millipore) were included in the kinase reaction. The reaction was stopped by adding 5 × SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) sample buffer, and the proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane followed by autoradiography and Western probed with an anti-FLAG antibody (1:5,000 dilution, Cat#. F4042, Sigma). The Western image in Supplementary Fig. 7b was cropped for presentation, and the full size image is presented in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Data Availability

All custom strains have been made available at http://cbs.umn.edu/cgc/home or http://shigen.nig.ac.jp/c.elegans/. Additional modified strains can be accessed upon request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Li, G. et al. Promotion of behavior and neuronal function by reactive oxygen species in C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 7, 13234 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13234 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-10 and Supplementary Table 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ursula Jakob for helpful discussion and sharing reagents, Eleni Gourgou, Daphne Bazopoulou and Nikos Chronis for assistance on setting up the microfluidic system and communicating unpublished results, and other lab members for technical assistance. Some strains were obtained from the CGC and Knockout Consortiums in the USA and Japan. This work utilized the Core Center for Vision Research funded by P30 EY007003 from the NEI. This work was supported by the NSFC (31130028, 31225011 and 31420103909 to J.L.), the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to the Universities from the Ministry of Education (B08029 to J.L.), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (PCSIRT: IRT13016) and the NIGMS (X.Z.S.X.).

Footnotes

Author contributions G.L. performed the experiments and analysed the data. J.G. performed the in vitro kinase assay and analysed the data. H.L. performed patch-clamp recordings and analysed the data. G.L., J.L. and X.Z.S.X. wrote the paper.

References

- Fridovich I. Oxygen: how do we stand it? Med. Princ. Pract. 22, 131–137 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb C. A. & Cole M. P. Oxidative and nitrative stress in neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 84, 4–21 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. T., Desikan R. & Neill S. J. Role of reactive oxygen species in cell signalling pathways. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 29, 345–350 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naziroglu M. TRPM2 cation channels, oxidative stress and neurological diseases: where are we now? Neurochem. Res. 36, 355–366 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 4350965 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz T. J. et al. Glucose restriction extends Caenorhabditis elegans life span by inducing mitochondrial respiration and increasing oxidative stress. Cell Metab. 6, 280–293 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristow M. & Schmeisser S. Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 327–336 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bono M. & Maricq A. V. Neuronal substrates of complex behaviors in C. elegans. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 28, 451–501 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumsta C., Thamsen M. & Jakob U. Effects of oxidative stress on behavior, physiology, and the redox thiol proteome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 14, 1023–1037 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard M. A., Bergamasco C., Arbucci S., Plasterk R. H. & Bazzicalupo P. Worms taste bitter: ASH neurons, QUI-1, GPA-3 and ODR-3 mediate quinine avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Embo J. 23, 1101–1111 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard M. A. et al. In vivo imaging of C. elegans ASH neurons: cellular response and adaptation to chemical repellents. Embo J. 24, 63–72 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A. C., Kass J., Shapiro J. E. & Kaplan J. M. Distinct signaling pathways mediate touch and osmosensory responses in a polymodal sensory neuron. J. Neurosci. 19, 1952–1958 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang G. H. et al. Protective effect of butylated hydroxylanisole against hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in primary cultured mouse hepatocytes. J. Vet. Sci. 16, 17–23 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George P. Reaction between catalase and hydrogen peroxide. Nature 159, 41–43 (1947). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann C. I., Hartwieg E. & Horvitz H. R. Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell 74, 515–527 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat N. R. & Zhang P. Hydrogen peroxide activation of multiple mitogen-activated protein kinases in an oligodendrocyte cell line: role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death. J. Neurochem. 72, 112–119 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P. P. & Blenis J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.: MMBR 68, 320–344 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisamoto N., Sakamoto R. & Matsumoto K. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in C. elegans. Int. Congr. Ser. 1246, 91–99 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi A., Matsumoto K. & Hisamoto N. Roles of MAP kinase cascades in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biochem. 136, 7–11 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser S., Zarse K. & Ristow M. Lonidamine extends lifespan of adult Caenorhabditis elegans by increasing the formation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Horm. Metab. Res. 43, 687–692 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarubin T. & Han J. Activation and signaling of the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Cell Res. 15, 11–18 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H. & Ausubel F. M. Evolutionary perspectives on innate immunity from the study of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17, 4–10 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H. et al. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science 297, 623–626 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann C. A., Cao J. & Manevich Y. Peroxiredoxin 1 and its role in cell signaling. Cell Cycle 8, 4072–4078 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Haes W. et al. Metformin promotes lifespan through mitohormesis via the peroxiredoxin PRDX-2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E2501–E2509 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis R. M., Hughes S. M. & Ledgerwood E. C. Peroxiredoxin 1 functions as a signal peroxidase to receive, transduce, and transmit peroxide signals in mammalian cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 1522–1530 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong W. S., Jun M. & Kong A. N. Nrf2: a potential molecular target for cancer chemoprevention by natural compounds. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 8, 99–106 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J. H. et al. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans oxidative stress defense protein SKN-1 by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16275–16280 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullet J. M. et al. Direct inhibition of the longevity-promoting factor SKN-1 by insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. Cell 132, 1025–1038 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn N. W., Rea S. L., Moyle S., Kell A. & Johnson T. E. Proteasomal dysfunction activates the transcription factor SKN-1 and produces a selective oxidative-stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. J. 409, 205–213 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert H. A., Smith T. L. & Bargmann C. I. OSM-9, a novel protein with structural similarity to channels, is required for olfaction, mechanosensation, and olfactory adaptation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 17, 8259–8269 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R. & Xu X. Z. S. Function and regulation of TRP family channels in C. elegans. Pflugers. Arch. 458, 851–860 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rane M. J. et al. p38 Kinase-dependent MAPKAPK-2 activation functions as 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-2 for Akt in human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3517–3523 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheesman H. K. et al. Aberrant activation of p38 MAP kinase-dependent innate immune responses is toxic to Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 6, 541–549 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis S. & Ruvkun G. Caenorhabditis elegans Akt/PKB transduces insulin receptor-like signals from AGE-1 PI3 kinase to the DAF-16 transcription factor. Genes Dev. 12, 2488–2498 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk J. M. & Hekimi S. Reactive oxygen species and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: causal or casual relationship? Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 13, 1911–1953 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser S. et al. Neuronal ROS signaling rather than AMPK/sirtuin-mediated energy sensing links dietary restriction to lifespan extension. Mol. Metab. 2, 92–102 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarse K. et al. Impaired insulin/IGF1 signaling extends life span by promoting mitochondrial L-proline catabolism to induce a transient ROS signal. Cell Metab. 15, 451–465 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozai D., Ogawa N. & Mori Y. Redox regulation of transient receptor potential channels. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 21, 971–986 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellem J. E., Brockie P. J., Zheng Y., Madsen D. M. & Maricq A. V. Decoding of polymodal sensory stimuli by postsynaptic glutamate receptors in C. elegans. Neuron 36, 933–944 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggott B. J., Liu J., Feng Z., Wescott S. A. & Xu X. Z. S. The neural circuits and synaptic mechanisms underlying motor initiation in C. elegans. Cell 147, 922–933 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis N., Zimmer M. & Bargmann C. I. Microfluidics for in vivo imaging of neuronal and behavioral activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Methods. 4, 727–731 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Feng Z., Sternberg P. W. & Xu X. Z. S. A C. elegans stretch receptor neuron revealed by a mechanosensitive TRP channel homologue. Nature 440, 684–687 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z. et al. A C. elegans model of nicotine-dependent behavior: regulation by TRP family channels. Cell 127, 621–633 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Kang L., Piggott B. J., Feng Z. & Xu X. Z. S. The neural circuits and sensory channels mediating harsh touch sensation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 2, 315 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A., Liu J., Feng Z. & Xu X. Z. Light-sensitive neurons and channels mediate phototaxis in C. elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 916–922 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Liu J., Zheng M. & Xu X. Z. Encoding of both analog- and digital-like behavioral outputs by one C. elegans interneuron. Cell 159, 751–765 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L., Gao J., Schafer W. R., Xie Z. & Xu X. Z. S. C. elegans TRP family protein TRP-4 is a pore-forming subunit of a native mechanotransduction channel. Neuron 67, 381–391 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. Z. S., Li H. S., Guggino W. B. & Montell C. Coassembly of TRP and TRPL produces a distinct store-operated conductance. Cell 89, 1155–1164 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-10 and Supplementary Table 1.

Data Availability Statement

All custom strains have been made available at http://cbs.umn.edu/cgc/home or http://shigen.nig.ac.jp/c.elegans/. Additional modified strains can be accessed upon request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.