Abstract

Mutations in the ATP-binding cassette transporter A3 gene (ABCA3) result in severe neonatal respiratory distress syndrome and childhood interstitial lung disease. As most ABCA3 mutations are rare or private, determination of mutation pathogenicity is often based on results from in silico prediction tools, identification in unrelated diseased individuals, statistical association studies, or expert opinion. Functional biologic studies of ABCA3 mutations are needed to confirm mutation pathogenicity and inform clinical decision making. Our objective was to functionally characterize two ABCA3 mutations (p.R288K and p.R1474W) identified among term and late-preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome with unclear pathogenicity in a genetically versatile model system. We performed transient transfection of HEK293T cells with wild-type or mutant ABCA3 alleles to assess protein processing with immunoblotting. We used transduction of A549 cells with adenoviral vectors, which concurrently silenced endogenous ABCA3 and expressed either wild-type or mutant ABCA3 alleles (p.R288K and p.R1474W) to assess immunofluorescent localization, ATPase activity, and organelle ultrastructure. Both ABCA3 mutations (p.R288K and p.R1474W) encoded proteins with reduced ATPase activity but with normal intracellular localization and protein processing. Ultrastructural phenotypes of lamellar body–like vesicles in A549 cells transduced with mutant alleles were similar to wild type. Mutant proteins encoded by ABCA3 mutations p.R288K and p.R1474W had reduced ATPase activity, a biologically plausible explanation for disruption of surfactant metabolism by impaired phospholipid transport into the lamellar body. These results also demonstrate the usefulness of a genetically versatile, human model system for functional characterization of ABCA3 mutations with unclear pathogenicity.

Keywords: surfactant, childhood interstitial lung disease, neonatal respiratory distress, respiratory distress syndrome

Clinical Relevance

Mutations in the ATP-binding cassette transporter A3 gene (ABCA3) result in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and childhood interstitial lung disease. However, most ABCA3 mutations are rare or private, and fewer than 10% of the approximately 200 identified mutations have been functionally characterized. Using adenoviral-mediated transduction of A549 cells and transfection of HEK293T cells, we functionally characterized two ABCA3 mutations (p.R288K and p.R1474W) identified among term and late-preterm infants with RDS. Our results suggest that both mutations encode proteins with reduced ATPase activity, a biologically plausible mechanism for neonatal RDS, but do not disrupt intracellular trafficking, protein processing, or phenotype of lamellar body–like vesicles. Characterization of ABCA3 mutations in a genetically versatile model system permits biologic confirmation of mutation pathogenicity, may inform counseling for affected families, and may suggest pharmacologic targets for correction.

ATP-binding cassette transporter A3 (ABCA3), a member of a large family of proteins that hydrolyze ATP to transport substances across biologic membranes, is encoded by an 80-kb gene (ABCA3; NM_001089.2, Gene ID 21) and consists of 1,704 amino acids with two membrane-spanning domains and two nucleotide binding domains. ABCA3 is expressed in alveolar type II cells, localizes to the membranes of lamellar bodies, and transports phospholipids into the lamellar body, where surfactant, a complex protein–phospholipid mixture that reduces surface tension and prevents alveolar collapse at end expiration, is assembled and stored (1–3). ABCA3 is also required for lamellar body biogenesis (4).

Biallelic loss-of-function (nonsense, frameshift) mutations in ABCA3 result in severe, progressive neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) that is lethal by 1 year of age without lung transplantation (5). However, for individuals with missense, splice site, and in-frame insertion/deletions, the presentation, disease severity, and prognosis range from severe neonatal RDS to childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD) (5). Monoallelic mutations in ABCA3 are overrepresented among term and late-preterm infants with reversible neonatal RDS (6, 7). Over 200 mutations in ABCA3 have been identified among infants and children from diverse ethnicities and geographic locations, and the majority of these mutations are rare or private (5, 6). Functional ABCA3 mutations interrupt intracellular trafficking of the protein to the lamellar body (type I) or reduce ATPase activity and impair phospholipid transport into the lamellar body (type II) (8, 9). However, fewer than 10% of ABCA3 mutations have been functionally characterized, and the locations of the mutations in the gene or the encoded protein do not reliably predict mutation pathogenicity (8–11). In silico algorithms can predict mutation-encoded disruption of protein function (12–14), but require confirmation in a biologic model system to inform clinical decision making.

ABCA3 mutations predicted in silico (14) to be pathogenic are present in 2.3% of over 60,000 individuals in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), Cambridge, MA (URL: http://exac.broadinstitute.org) [accessed January 2016]). However, fewer than 10 infants per year undergo lung transplantation for ABCA3 deficiency (15), suggesting that prediction programs may overestimate frequency of disruptive mutations, some infants may be unrecognized, additional phenotypes may exist, or other genetic or environmental factors may modify disease presentation. With the increased availability of ABCA3 sequencing for symptomatic infants and children, the variable prognosis for individuals with missense, splice site, and in-frame insertion/deletions, and the limited functional prediction data, methods to distinguish pathogenic mutations from benign variants are needed to inform clinical decision making, predict disease trajectory, and assess recurrence risk (16). To functionally characterize two ABCA3 mutations identified among infants with RDS with unclear pathogenicity (c. 863G>A, p.R288K and c.4420C>T, p.R1474W), we used adenoviral vector–mediated concurrent silencing of endogenous ABCA3 expression and rescue with wild-type or mutant ABCA3 alleles in A549 cells to compare immunofluorescent localization, ATPase activity, and organelle ultrastructure. We transiently transfected HEK293T cells with wild-type or mutant ABCA3 alleles and used protein immunoblotting to compare protein processing. Our results demonstrate the usefulness of a genetically versatile human model system for functional testing of ABCA3 mutations which could be adapted for testing pharmacologic correction of encoded defects.

Materials and Methods

Mutation Selection

We selected two previously uncharacterized ABCA3 mutations, p.R288K and p.R1474W, because in silico prediction tools and statistical associations did not concur about each mutation’s pathogenicity. In a study of term and late-preterm infants with RDS (6), p.R288K was overrepresented among European-descent infants with RDS (5.3% RDS versus 1.2% non-RDS infants), whereas p.R1474W was similarly represented (0.9% RDS versus 1.9% non-RDS) (6). However, in silico prediction with ANNOVAR (URL: http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/ [accessed May 2016]), an annotation tool that provides results from six independent variant functional prediction algorithms, suggests that p.R288K is benign and p.R1474W is pathogenic (14, 17). Unclear pathogenicity of these mutations based on statistical associations and in silico results and their relatively high population-based collapsed frequency (1.1% in ExAC) (18) complicate prediction of disease course and assessment of recurrence risk (18). We also characterized two ABCA3 mutations known to interrupt protein localization (p.L101P, type I mutation) and decrease ATP hydrolysis (p.E292V, type II mutation) to serve as positive controls.

ABCA3/GFP Constructs

Wild-type and mutant ABCA3 cDNAs (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were cloned into the AcGFP1-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) vector in-frame with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and verified by Sanger sequencing. Constructs for the two uncharacterized (p.R288K and p.R1474W) and two characterized (p.L101P and p.E292V) mutations were generated by mutagenesis using ABCA3 WT_GFP as a template and verified by sequencing.

shRNA/ABCA3/GFP Constructs

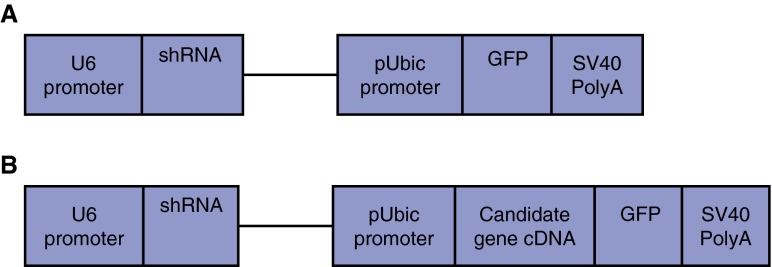

Adenoviral vectors were constructed for wild-type ABCA3 and mutants (Figure 1) (19). See online supplement for details.

Figure 1.

(A and B) Construction of adenoviral expression cassettes. cDNA, complementary DNA; GFP, green fluorescent protein; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; SV40, Simian virus 40.

Transduction of A549 Cells and Extraction of Membrane Protein

A549 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were plated on six-well plates (300,000 cells/well) for 24 hours, incubated for 2 hours with adenovirus that expressed wild-type or mutant ABCA3 constructs (p.R288K, p.R1474W, p.L101P, p.E292V; 3,000 VP/cell in 2% FBS/F12K), washed, and provided with fresh 10% FBS/F12K medium. Immunohistochemistry was performed 24 hours after viral transduction and membrane protein was extracted (see online supplement).

Transfection of HEK293T Cells

We transiently transfected HEK293T cells (3 μg wild-type ABCA3 or mutant ABCA3 plasmid DNA/dish; ATCC, Manassas, VA) on 100-mm dishes using Fugene6 (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and total protein was extracted.

Immunoblotting

See the online supplement for details.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy Imaging

See the online supplement for details.

ATPase Assay

Using a colorimetric ATPase assay kit (Innova Biosciences, Cambridge, UK) and triplicate measurements with 10 μg of membrane protein for each assay, we assessed ATP hydrolysis activity by measuring the free v-phosphate released from ATP in 96-well plates following the manufacturer’s recommendations (see the online supplement).

Electron Microscopy

After fixation (2% glutaraldehyde for 4 h at 4°C), cells were postfixed (2% osmium tetroxide for 1 h), en bloc stained (2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 30 min), dehydrated, and embedded in PolyBed 812 (Polysciences, Hatfield, PA). Sections (90 nm) were poststained (Venable’s lead citrate) and viewed with a JEOL model 1200EX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Digital images were acquired using an AMT Advantage HR (Advanced Microscopy Technology, Danvers, MA) high-definition charge-coupled device, 1.3-megapixel transmission electron microscopy camera.

Results

Subcellular Immunofluorescent Localization and Immunoblotting

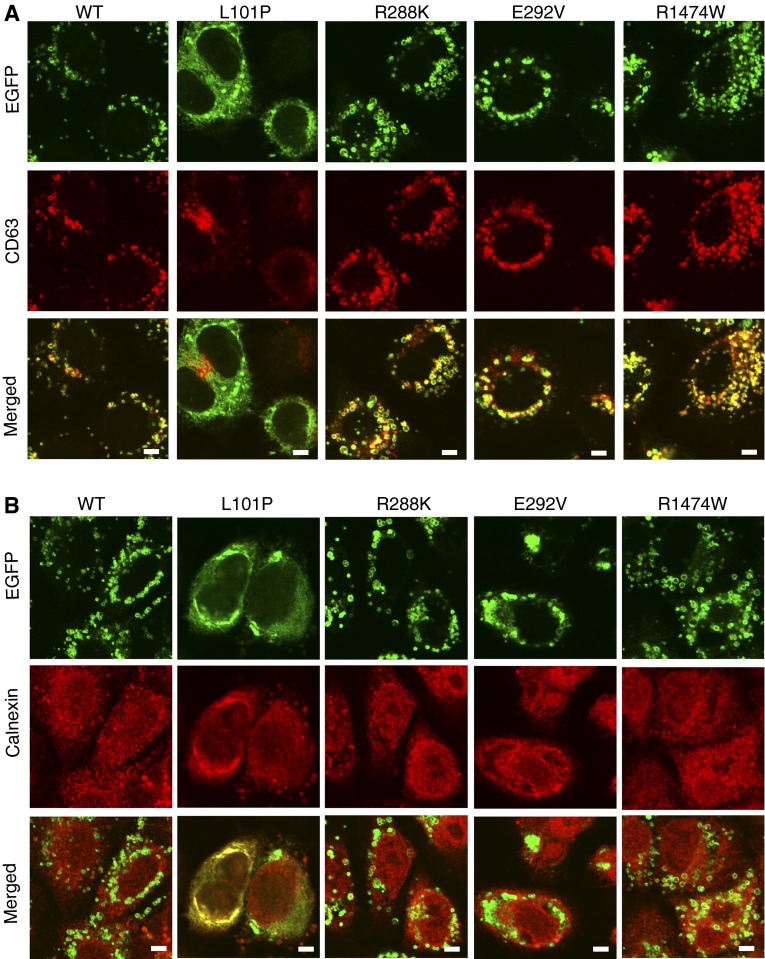

Using A549 cells transduced with either wild-type or mutant ABCA3_GFP, we found that both R288K_GFP and R1474W_GFP colocalize to lamellar body–like vesicles and demonstrate dotted ring–like patterns, similar to wild type (Figure 2A). We confirmed the results of previous studies that E292V_GFP colocalizes to lysosomally derived lamellar body–like vesicles (Figure 2A), and L101P_GFP colocalizes to the endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A and B) Intracellular immunofluorescent localization of wild-type (WT) ABCA3_GFP and mutant proteins. A549 cells transfected with WT ABCA3 or mutations, p.L101P, p.E292V, p.R288K, and p.R1474W, were analyzed using confocal microscopy. Anti-CD63 and anti-calnexin were used to stain lysosomally derived lamellar body–like vesicles and endoplasmic reticulum, respectively. Scale bars, 5 μm (n = 3 replicates per condition). ABCA3, ATP-binding cassette transporter A3; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

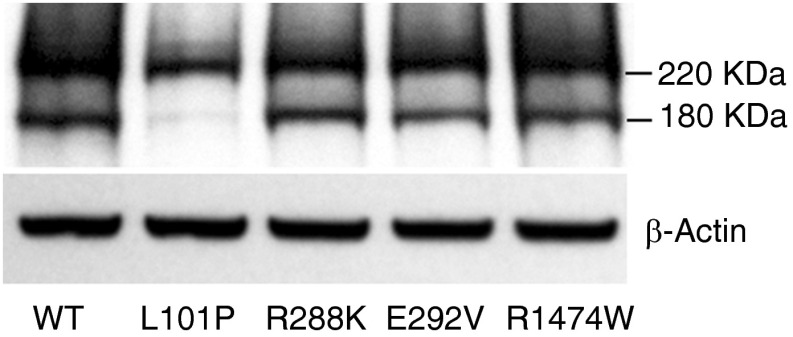

Mutations that interrupt ABCA3 intracellular trafficking (type I) also disrupt ABCA3 protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Previous studies have demonstrated two protein bands at 220 and 180 kD that represent noncleaved and cleaved forms of wild-type ABCA3_GFP and a single 220-kD noncleaved band for mutant proteins that disrupt intracellular trafficking (e.g., L101P, type I mutation) (8, 9, 11). Using immunoblotting of total cellular protein from HEK293T cells transiently transfected with wild-type or mutant ABCA3 plasmid DNA, we observed two bands corresponding to cleaved and noncleaved forms for wild-type, E292V, R288K, and R1474W proteins (Figure 3). We confirmed the results of previous studies with a single 220-kD band observed for the trafficking mutant, p.L101P. Based on our localization and immunoblotting studies, p.R288K and p.R1474W do not disrupt intracellular ABCA3 protein trafficking or ABCA3 processing.

Figure 3.

Immunoblotting analysis in cells transiently transfected with WT ABCA3 or p.L101P, p.E292V, p.R288K, and p.R1474W mutations. ABCA3 expression was detected using anti-GFP antibody and normalized with β-actin (n = 3 replicates per conditions).

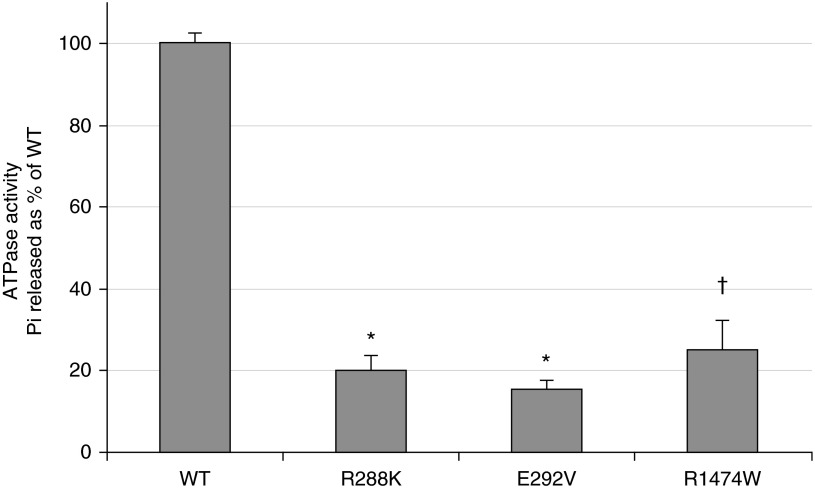

ATPase Assay

To determine whether p.R288K and p.R1474W impair ATP hydrolysis (type II mutation), we extracted membrane protein from adenoviral-transduced A549 cells, performed a colorimetric ATPase assay, and compared results to a previously characterized ATP hydrolysis mutation, p.E292V (20). We found that, similar to p.E292V, both p.R288K (80% reduction, P < 0.0001) and p.R1474W (75% reduction, P = 0.0012) encoded ABCA3 proteins with significantly reduced ATPase activity compared with wild type (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

ATPase activity of WT ABCA3 and mutant proteins. ATPase activity was measured as free v-phosphate (Pi) released, compared with WT ABCA3 activity, and normalized to Western blot with anti-GFP antibody. Error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3 replicates per condition). All three mutant proteins had significantly reduced ATPase activity compared with WT ABCA3. *P < 0.0001; †P = 0.0012.

Organelle Ultrastructure

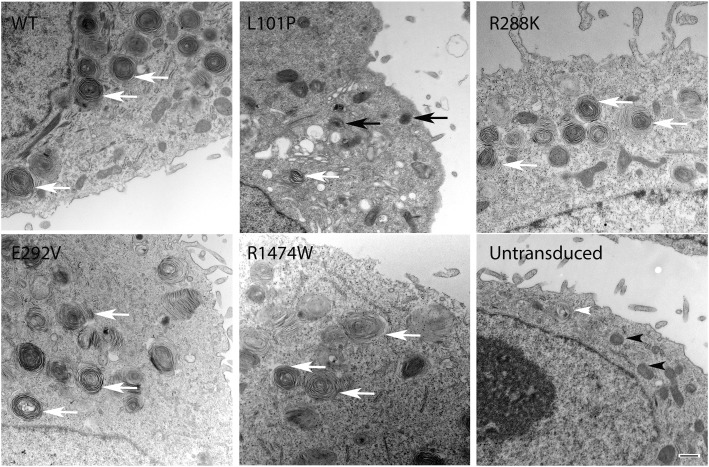

Lamellar bodies in alveolar type II cells from infants and children with ABCA3 mutations often appear small, with densely packed membranes and eccentric, round, dense inclusions, although more normal-appearing lamellar bodies have also been reported (21–23). We compared organelle ultrastructure using A549 cells transduced with adenoviral vectors that expressed wild-type ABCA3 or the mutant alleles (Figure 5). As shown previously (10, 24), we found that transduction of A549 cells with wild-type ABCA3 resulted in formation of lamellar body–like vesicles (Figure 5). Cells transduced with p.E292V, p.R288K, and p.R1474W appeared similar to wild type with multiple well organized lamellar body–like vesicles (Figure 5). Cells transduced with p.L101P had abnormal-appearing lamellar body–like vesicles with irregular lamellae and dense inclusions and fewer well organized lamellar body–like vesicles compared with wild type.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopy imaging of A549 cells transduced with WT ABCA3, p.L101P, p.E292V, p.R288K, and p.R1474W. A549 cells transduced with p.E292V, p.R288K, and p.R1474W appeared similar to WT with multiple, well-organized lamellar body–like vesicles. Cells transduced with p.L101P had frequent abnormal-appearing lamellar body–like vesicles with dense inclusions and fewer well-organized lamellar body–like vesicles compared with cells transduced with WT. White arrows indicate well-organized lamellar body–like vesicles; black arrows indicate abnormal-appearing lamellar body–like vesicles; white arrowhead indicates lamellar body–like structure in untransduced cells; black arrowheads indicate mitochondria. Scale bar, 0.5 μm (n = 10 cells examined per condition).

Discussion

Using functional studies, we determined that both p.R288K and p.R1474W encode ABCA3 with normal trafficking and protein processing, but decreased ATPase activity. Although the lamellar body–like vesicle phenotypes of both p.R288K and p.R1474W were similar to wild-type ABCA3 and p.E292V, a previously characterized type II mutation, decreased ATPase activity provides a plausible biological mechanism for the neonatal respiratory phenotype (RDS) associated with these mutations. These findings also suggest that, in A549 cells, reduced ATP hydrolysis activity of ABCA3 does not disrupt biogenesis of lamellar body–like vesicles. The ExAC frequencies of p.R288K (0.6%) and p.R1474W (0.5%) are similar to that of p.E292V (0.2%), the most common ABCA3 mutation associated with chILD (5, 23, 25, 26). Five individuals homozygous for p.R288K and five individuals homozygous for p.R1474W are reported in ExAC; however, their phenotypes are not described. Pathogenicity of p.R288K is suggested by its overrepresentation among late-preterm and term infants with RDS (6, 7), its identification in twin infants with severe, but nonlethal, respiratory failure (these infants also had two other ABCA3 mutations in cis and trans with p.R288K) (5), its identification in term infants with lethal RDS (in trans with p.Q215K in one infant; in combination with p.R43L, c.4751 delT, and p.P585P in two siblings) (27), and by its location in the first intracellular loop of the mature ABCA3 protein, similar to the location of p.E292V. The conservative substitution of amino acids with positively charged side chains encoded by p.R288K may account for computational prediction of nonpathogenicity. Our studies suggest that the pathogenicity of p.R1474W is attributable to reduced ATPase activity despite its location in the second nucleotide-binding domain of ABCA3 similar to a previously characterized mutation (p.G1518V fs*2), which encodes impaired intracellular trafficking (9). Failure to find the p.R1474W mutation among 185 infants and children with biallelic ABCA3 mutations and a phenotype of surfactant deficiency (5), and similar frequencies of p.R1474W among term and late-preterm infants with and without RDS (6), suggest that the in vivo reduction in ATPase activity encoded by p.R1474W may be less than p.E292V or p.R288K, or that other genetic or environmental factors (e.g., gestational age, sex, delivery route) may contribute to disease penetrance. Our studies suggest pathogenicity of p.R288K and p.R1474W, but do not account for the phenotypic diversity in symptomatic infants and children.

A limitation of our study was the use of immortalized cell lines (A549 and HEK293T) that do not produce functional surfactant rather than a surfactant-producing cell system (e.g., primary alveolar type II cells) to characterize ABCA3 mutation function. However, lack of ready access to primary human alveolar type II cells, their rapid differentiation in culture to alveolar type I cells, and the genetic versatility of adenoviral transduction or transfection of immortalized cells make this model system useful for functional characterization of ABCA3 mutations and potential identification of small molecules to correct encoded defects. Work to develop patient-specific alveolar type II cells from fibroblasts reprogrammed to become induced pluripotent stem cells will permit functional study of ABCA3 mutations within a subject’s genetic background (28).

Similar to mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator, another member of the ATP-binding cassette transporter family, ABCA3 mutations may disrupt protein function by not only interrupting intracellular trafficking or decreasing ATPase activity, but also by reducing ABCA3 synthesis or stability (29). Variability in ABCA3 deficiency phenotype may result from mechanisms other than intracellular trafficking and decreased ATPase activity, and emphasizes the importance of model systems for determination of mutation pathogenicity. Developing model systems for standardized functional testing of rare or private genomic variants is necessary to inform family discussions about prognosis of affected infants and children, correlate genotype with phenotype, predict reproductive recurrence risk, and develop strategies for pharmacologic correction of encoded defects.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K08 HL105891 (J.A.W.), K12 HL120002 (F.S.C.), R01 HL065174 (F.S.C. and A.H.), R01 HL082747 (F.S.C. and A.H.), and R21 HL120760 (F.S.C.), by the American Thoracic Society (J.A.W.), the American Lung Association (J.A.W.), the Children’s Discovery Institute (F.S.C.), and the Saigh Foundation (F.S.C.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design—J.A.W., P.Y., D.J.W., H.B.H., D.T.C., A.H., B.P.H., and F.S.C.; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data—J.A.W., P.Y., D.J.W., H.B.H., L.N.K., S.A.K., D.T.C., F.V.W., A.H., B.P.H., and F.S.C.; drafting and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content—J.A.W., P.Y., A.H., B.P.H., and F.S.C.; all authors have approved the final version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0008OC on July 2, 2016

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald ML, Xavier R, Haley KJ, Welti R, Goss JL, Brown CE, Zhuang DZ, Bell SA, Lu N, McKee M, et al. ABCA3 inactivation in mice causes respiratory failure, loss of pulmonary surfactant, and depletion of lung phosphatidylglycerol. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:621–632. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600449-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulugeta S, Gray JM, Notarfrancesco KL, Gonzales LW, Koval M, Feinstein SI, Ballard PL, Fisher AB, Shuman H. Identification of LBM180, a lamellar body limiting membrane protein of alveolar type II cells, as the ABC transporter protein ABCA3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22147–22155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ban N, Matsumura Y, Sakai H, Takanezawa Y, Sasaki M, Arai H, Inagaki N. ABCA3 as a lipid transporter in pulmonary surfactant biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9628–9634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheong N, Zhang H, Madesh M, Zhao M, Yu K, Dodia C, Fisher AB, Savani RC, Shuman H. ABCA3 is critical for lamellar body biogenesis in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23811–23817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wambach JA, Casey AM, Fishman MP, Wegner DJ, Wert SE, Cole FS, Hamvas A, Nogee LM. Genotype-phenotype correlations for infants and children with ABCA3 deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1538–1543. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0342OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wambach JA, Wegner DJ, Depass K, Heins H, Druley TE, Mitra RD, An P, Zhang Q, Nogee LM, Cole FS, et al. Single ABCA3 mutations increase risk for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1575–e1582. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naderi HM, Murray JC, Dagle JM. Single mutations in ABCA3 increase the risk for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in late preterm infants (gestational age 34–36 weeks) Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:2676–2678. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheong N, Madesh M, Gonzales LW, Zhao M, Yu K, Ballard PL, Shuman H. Functional and trafficking defects in ATP binding cassette A3 mutants associated with respiratory distress syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9791–9800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumura Y, Ban N, Ueda K, Inagaki N. Characterization and classification of ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA3 mutants in fatal surfactant deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34503–34514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flamein F, Riffault L, Muselet-Charlier C, Pernelle J, Feldmann D, Jonard L, Durand-Schneider AM, Coulomb A, Maurice M, Nogee LM, et al. Molecular and cellular characteristics of ABCA3 mutations associated with diffuse parenchymal lung diseases in children. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:765–775. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weichert N, Kaltenborn E, Hector A, Woischnik M, Schams A, Holzinger A, Kern S, Griese M. Some ABCA3 mutations elevate ER stress and initiate apoptosis of lung epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2011;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan MS, Heinle JS, Samayoa AX, Adachi I, Schecter MG, Mallory GB, Morales DL. Is lung transplantation survival better in infants? Analysis of over 80 infants. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wambach JA, Wegner DJ, Heins HB, Druley TE, Mitra RD, Hamvas A, Cole FS. Synonymous ABCA3 variants do not increase risk for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1316–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu W, O’Connor TD, Jun G, Kang HM, Abecasis G, Leal SM, Gabriel S, Rieder MJ, Altshuler D, Shendure J, et al. NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein–coding variants Nature 2013493216–220.[Published erratum appears in Nature 495:270.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Leal SM. Methods for detecting associations with rare variants for common diseases: application to analysis of sequence data. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2509–2514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumura Y, Ban N, Inagaki N. Aberrant catalytic cycle and impaired lipid transport into intracellular vesicles in ABCA3 mutants associated with nonfatal pediatric interstitial lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L698–L707. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90352.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulenin S, Nogee LM, Annilo T, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M. ABCA3 gene mutations in newborns with fatal surfactant deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1296–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tryka AF, Wert SE, Mazursky JE, Arrington RW, Nogee LM. Absence of lamellar bodies with accumulation of dense bodies characterizes a novel form of congenital surfactant defect. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2000;3:335–345. doi: 10.1007/s100249910048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doan ML, Guillerman RP, Dishop MK, Nogee LM, Langston C, Mallory GB, Sockrider MM, Fan LL. Clinical, radiological and pathological features of ABCA3 mutations in children. Thorax. 2008;63:366–373. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.083766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumura Y, Sakai H, Sasaki M, Ban N, Inagaki N. ABCA3-mediated choline-phospholipids uptake into intracellular vesicles in A549 cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3139–3144. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bullard JE, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M, Nogee LM. ABCA3 mutations associated with pediatric interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1026–1031. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-504OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nogee LM. Genetics of pediatric interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:287–292. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000193310.22462.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brasch F, Schimanski S, Mühlfeld C, Barlage S, Langmann T, Aslanidis C, Boettcher A, Dada A, Schroten H, Mildenberger E, et al. Alteration of the pulmonary surfactant system in full-term infants with hereditary ABCA3 deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:571–580. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1535OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotton DN, Morrisey EE. Lung regeneration: mechanisms, applications and emerging stem cell populations. Nat Med. 2014;20:822–832. doi: 10.1038/nm.3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyle MP, De Boeck K. A new era in the treatment of cystic fibrosis: correction of the underlying CFTR defect. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:158–163. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]