Abstract

Objective:

Growth retardation is common in children with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) and growth hormone (GH) resistance may play a dominant role. The aim of this study was to ascertain growth parameters and growth-related hormones in children with EHPVO, comparing with controls and to study the response of shunt surgery on growth parameters.

Materials and Methods:

The auxological and growth-related hormone profile (GH; insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 [IGFBP-3] and IGF-1) of thirty children with EHPVO were compared with controls. The effect of shunt surgery on growth parameters in 12 children was also studied.

Results:

The mean height standard deviation score (HSDS) of cases (−1.797 ± 1.146) was significantly lower than that of controls (−0.036 ± 0.796); the mean weight SDS of cases (−1.258 ± 0.743) was also lower than that of controls (−0.004 ± 0.533). The mean GH level of cases (5.00 ± 6.46 ng/ml) was significantly higher than that of controls (1.78 ± 2.04 ng/ml). The mean IGF-1 level of cases (100.25 ± 35.93 ng/ml) was significantly lower as compared to controls (233.53 ± 115.06 ng/ml) as was the mean IGFBP-3 level (2976.53 ± 1212.82 ng/ml in cases and 5183.28 ± 1531.28 ng/ml in controls). In 12 patients who underwent shunt surgery, growth parameters significantly improved.

Conclusions:

Marked decrease in weight and height SDSs associated with GH resistance is seen in children with EHPVO, which improves with shunt surgery.

Key words: Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction, growth hormone resistance, growth retardation, shunt surgery

INTRODUCTION

Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) is a vascular disorder of the liver defined by the obstruction and cavernomatous transformation of the main portal vein.[1] It is characterized by noncirrhotic, presinusoidal, and prehepatic portal hypertension.[2] EHPVO is the most common cause of portal hypertension and an important cause of major upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children.[3,4] Although several studies, mostly from the Indian subcontinent, have documented the growth retardation in children with EHPVO,[5,6,7,8] details of causes of growth failure are not clear. One study demonstrated a normal to high basal growth hormone (GH) coupled with low insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) suggesting possible GH resistance as a cause of short stature.[6] Another study reported low IGF-1 and IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) levels suggesting a similar mechanism, however, GH levels were not estimated.[5] IGF-1 assays have intrinsic limitations and variability subjected to age, nutritional status, and potential interference of IGFBPs.[9] Measurement of IGFBP-3 together with the assay of IGF-1 overcomes some of these limitations, and such a combination is a more specific marker of GH status.[10] To the best of our knowledge, none of the studies has utilized all three hormones (GH, IGFBP-3, and IGF-1) to understand the cause of short stature in these patients. Keeping in view the limitations of the above studies and utility of a combined measurement of GH, IGFBP-3, and IGF-1, the present case–control study was designed. The aim of the present study was to assess the auxological parameters and GH status (using a combination of GH, IGFBP-3, and IGF-1) in children with EHPVO. Since shunt surgery has been found to improve growth in these children;[8,11,12] we also studied the effect of shunt surgery on these auxological parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cases and controls

Thirty consecutive children (18 boys and 12 girls) seen at a tertiary care center in North India and diagnosed to have EHPVO were enrolled in the study from May 2012 to December 2014. The diagnosis of EHPVO was based on clinical features, normal liver functions, endoscopic evidence of esophagogastric varices, and ultrasonographic findings of blocked or recanalized portal vein with the formation of portal cavernoma.[13] The exclusion criteria included: Any other concomitant systemic disease such as tuberculosis, bronchial asthma, hypothyroidism, renal, or cardiac disease; laboratory evidence of hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection; and refusal to participate in the study.

Thirty age and sex matched, well-nourished, healthy children served as controls. The controls were drawn from among the patients’ siblings or first cousins. This study was submitted to and approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee.

Clinical workup

A detailed general physical and systemic examination was performed in cases and controls. Height was measured on a wall-mounted stadiometer by one observer throughout the study period, with the patient's head held in Frankfurt plane (line connecting the outer canthus of the eyes and the external auditory meatus perpendicular to the long axis of the trunk). Weight was measured on an electronic balance with digital display with a minimum division of 100 g. Height and weight indices were expressed as percentiles and standard deviation scores (SDS) calculated from growth charts described by Agarwal et al., these charts from India provide an index of deviation from national standards in growth from birth to 18 years.[14,15]

Laboratory workup

At the baseline, detailed hemogram, urine analysis, serum biochemistry (liver and kidney function), and coagulogram were obtained in patients and controls. Hormonal workup included measurement of GH, IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 for both patients and controls. A fasting serum sample was taken for GH, IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 and samples were preserved at −30C until processed. GH assay was done by chemiluminescence immunometric assay on Beckman Coulter DXI 800, IGF-1 assay was done by RAYBIO® Human IGF-1 Elisa Kit protocol, and IGFBP-3 was done by RAYBIO® Human IGFBP3 Elisa Kit Protocol. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation of IGF-1/IGFBP-3 assays was <10% and <12%, respectively.

Shunt surgery

Twelve cases underwent shunt surgery. Shunt procedures were performed by a single experienced surgeon. Proximal splenorenal shunt was performed which involved removal of the spleen with end-to-side anastomosis of the end of the splenic vein to the side of the left renal vein. In these 12 cases, we compared the growth parameters before surgery with those of 2 years after surgery.

RESULTS

Thirty patients with EHPVO (18 males and 12 females) and thirty controls patients (18 males and 12 females) participated in the study. The cases and controls were similar regarding age. The mean age of cases was 12.43 ± 4.12 years and that of controls was 13.77 ± 3.02 years. Eighteen out of thirty patients had height <5th percentiles as against one in controls indicating growth retardation in 60% of the cases as against 3% in controls. Similarly, twenty out of thirty patients had weight <5th percentiles as against two in controls. The mean height SDS (HSDS) of children with EHPVO was significantly less than those of controls (−1.797 ± 1.146 for cases and −0.036 ± 0.796 for controls; P < 0.0001). Similarly, the mean weight SDS (WSDS) of children with EHPVO was significantly less than that of controls (−1.258 ± 0.743 for cases and −0.004 ± 0.533 for controls; P < 0.0001).

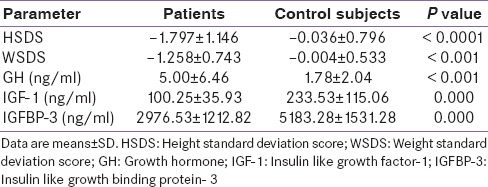

The mean fasting GH level was significantly higher in patients as compared to controls, (P < 0.001). Both the mean fasting IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels were significantly lower in patients as compared to controls (P < 0.001 for both) [Table 1]. The mean fasting IGF-1 level of cases was 100.25 ± 35.93 ng/ml while that of controls was 233.53 ± 115.06 ng/ml. Similarly, the mean fasting IGFBP-3 levels of cases were 2976.53 ± 1212.82 ng/ml while that of controls was 5183.28 ± 1531.28 ng/ml. The growth parameters and growth-related hormone profile in patients and controls are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Growth parameters and growth-related hormone profile in patients and controls

Of the 30 patients, 12 underwent shunt surgery. In these 12 cases, we compared the growth parameters (HSDS and WSDS) before surgery with those of 2 years after surgery. The mean HSDS significantly improved from −2.08 ± 1.31 before surgery to −1.28 ± 0.73 after surgery. The WSDS similarly improved from −1.536 ± 0.65 before surgery to −0.86 ± 0.23 after surgery.

DISCUSSION

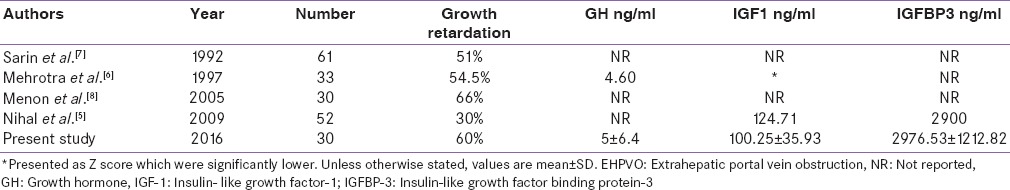

EHPVO is the most common cause of noncirrhotic portal hypertension in India [16] and accounts for 40% cases of portal hypertension in children.[17] Previous studies from India have reported the growth retardation in patients with EHPVO compared with age- and sex-matched controls.[5,6,7,8] In the study by Sarin et al.,[7] 51% of children with EHPVO had stunted growth as against 16% of controls (P < 0.01). Mehrotra et al.[6] in a study of 33 patients reported that 54.5% of patients were below the 5th percentile in height. In another Indian study, more than one-third of children with EHPVO had height and/or weight Z-scores more than two standard deviations below the mean.[8] Another Indian study reported that six of the twenty (30%) patients of EHPVO younger than 18 years were below the 5th percentile in height.[5] Our results are consistent with other Indian studies. In our study, the HSDS and WSDS of cases were significantly lower than that of controls. In addition, in the present study, growth retardation was seen in 60% of our patients. Bellomo-Brandão et al.[18] in a retrospective analysis of 24 patients with EHPVO reported that EHPVO was not associated with growth impairment; however, this study lacked a control group. The comparison of our study with other studies is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of main findings on EHPVO and growth parameters

The causes of growth retardation in children with EHPVO are not completely understood. Portal venous congestion of the gut, concurrent malabsorption, and anorexia from splenomegaly may contribute to poor nutrition and growth in extrahepatic portal hypertension. In a study of 11 children with prehepatic portal vein obstruction, the ability of the small gut to absorb specific monosaccharides was reduced.[19] Studies have yielded contradictory results about the role of deficient nutritional intake in these patients.[6,7]

For diagnosing GH deficiency, the combination of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 has a markedly better sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity 97% and specificity 95%) as compared to IGF-1 alone.[10,20] Few studies have evaluated GH-IGF-1 axis in patients with EHPVO. Mehrotra et al.[6] reported a pattern of elevated GH and decreased IGF-1 levels suggesting a state of GH resistance. Another study involving 52 patients of EHPVO reported low IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels, suggesting a similar mechanism; however, they did not estimate GH levels.[5] In our study, we studied a combination of IGF-1, IGFBP-3, and GH. We documented high GH, low IGF-1, and low IGFBP-3 levels in EHPVO cohort compared to sex- and age-matched healthy controls. Thus, our study suggests that GH resistance is responsible for growth retardation in patients with EHPVO. GH resistance has been documented in previous studies on adults with portal hypertension caused by cirrhosis,[21,22] as well as in children with chronic liver disease, with or without portal hypertension.[23] The cause of GH resistance in EHPVO is elusive. EHPVO has been shown to result in diminished portal blood flow,[24] and this has been demonstrated in cirrhotic patients to result in decreased insulin delivery to the liver.[25] There is also evidence from animal studies that portal vein ligation leads to poor hepatic growth, as well as mitochondrial dysfunction during the phase of decreased hepatic blood flow.[26] This may result in GH receptor defect or a postreceptor signaling defect.

Effect of shunt surgery

Twelve patients underwent proximal splenorenal shunt. In these patients, we documented a significant improvement in height and WSDS, 2 years after shunt surgery. Few studies have reported the effect of shunt surgery on growth parameters in children with EHPVO. A striking increase in growth velocity after portosystemic shunt surgery for extrahepatic portal hypertension was first reported in 1983 by Alvarez et al.[11] In a randomized, controlled study, Kato et al.[12] reported that children with EHPVO who underwent shunt surgery had a significant improvement in growth compared with children who did not undergo surgery. Finally, in a study of thirty children with EHPVO, 76% showed improvement in height Z-scores compared to their presurgical scores after shunt surgery.[8]

CONCLUSIONS

We documented that the height and weight SDSs of children with EHPVO were significantly lower than that of sex- and age-matched controls. Evaluation of GH-IGF-1 axis revealed GH resistance responsible for growth retardation in these patients. Finally, in 12 patients, who underwent shunt surgery, a significant increase in weight and height SDS was seen after shunt surgery.

Limitations

A small sample size may be a limitation, however even the sample size of sixty (thirty cases and thirty controls) was sufficient to draw the aforementioned conclusions. The strength of the study lies in complete evaluation of GH-IGF-1 axis

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sarin SK, Sollano JD, Chawla YK, Amarapurkar D, Hamid S, Hashizume M, et al. Consensus on extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction. Liver Int. 2006;26:512–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gauthier F. Recent concepts regarding extra-hepatic portal hypertension. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14:216–25. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard ER, Stringer MD, Mowat AP. Assessment of injection sclerotherapy in the management of 152 children with oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1988;75:404–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarin SK, Misra SP, Singal AK, Thorat V, Broor SL. Endoscopic sclerotherapy for varices in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:662–6. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nihal L, Bapat MR, Rathi P, Shah NS, Karvat A, Abraham P, et al. Relation of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 levels to growth retardation in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:305–9. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9102-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehrotra RN, Bhatia V, Dabadghao P, Yachha SK. Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction in children: Anthropometry, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor I. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:520–3. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarin SK, Bansal A, Sasan S, Nigam A. Portal-vein obstruction in children leads to growth retardation. Hepatology. 1992;15:229–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menon P, Rao KL, Bhattacharya A, Thapa BR, Chowdhary SK, Mahajan JK, et al. Extrahepatic portal hypertension: Quality of life and somatic growth after surgery. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:82–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furlanetto RW. Insulin-like growth factor measurements in the evaluation of growth hormone secretion. Horm Res. 1990;33(Suppl 4):25–30. doi: 10.1159/000181580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum WF, Ranke MB. Use of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 for the evaluation of growth disorders. Horm Res. 1990;33(Suppl 4):31–7. doi: 10.1159/000181581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez F, Bernard O, Brunelle F, Hadchouel P, Odievre M, Alagille D, et al. Portal obstruction in children; Part II. Results of surgical portosystemic shunts. J Pediatr. 1983;103:703–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato T, Romero R, Koutouby R, Mittal NK, Thompson JF, Schleien CL, et al. Portosystemic shunting in children during the era of endoscopic therapy: Improved postoperative growth parameters. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:419–25. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200004000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna R, Sarin SK. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension - Diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2014;60:421–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal DK, Agarwal KN, Upadhyay SK, Mittal R, Prakash R, Rai S. Physical and sexual growth pattern of affluent Indian children from 5 to 18 years of age. Indian Pediatr. 1992;29:1203–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal DK, Agarwal KN. Physical growth in Indian affluent children (birth-6 years) Indian Pediatr. 1994;31:377–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarin SK, Agarwal SR. Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:43–58. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panda MK, Jain PK, Gupta S, Nihal L, Bapat MR, Rathi PM. Profile of pediatric portal hypertension in a tertiary hospital in Western India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:A134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellomo-Brandão MA, Morcillo AM, Hessel G, Cardoso SR, Servidoni Mde F, da-Costa-Pinto EA. Growth assessment in children with extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction and portal hypertension. Arq Gastroenterol. 2003;40:247–50. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032003000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor RM, Bjarnason I, Cheeseman P, Davenport M, Baker AJ, Mieli-Vergani G, et al. Intestinal permeability and absorptive capacity in children with portal hypertension. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:807–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenfeld RG, Wilson DM, Lee PD, Hintz RL. Insulin-like growth factors I and II in evaluation of growth retardation. J Pediatr. 1986;109:428–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shankar TP, Solomon SS, Duckworth WC, Jerkins T, Iyer RS, Bobal MA. Growth hormone and carbohydrate intolerance in cirrhosis. Horm Metab Res. 1988;20:579–83. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Møller S, Juul A, Becker U, Flyvbjerg A, Skakkebaek NE, Henriksen JH. Concentrations, release, and disposal of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding proteins (IGFBP), IGF-I, and growth hormone in different vascular beds in patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1148–57. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.4.7536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucuvalas JC, Cutfield W, Horn J, Sperling MA, Heubi JE, Campaigne B, et al. Resistance to the growth-promoting and metabolic effects of growth hormone in children with chronic liver disease. J Pediatr. 1990;117:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lebrec D, Bataille C, Bercoff E, Valla D. Hemodynamic changes in patients with portal vein obstruction. Hepatology. 1983;3:550–3. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosch J, Gomis R, Kravetz D, Casamitjana R, Tere’s J, Rivera F, et al. Role of spontaneous portal-systemic shunting in hyperinsulinism of cirrhosis. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:G206–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.247.3.G206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omokawa S, Asanuma Y, Koyama K. Evaluation of hemodynamics and hepatic mitochondrial function on extrahepatic portal obstruction in the rat. World J Surg. 1990;14:247–53. doi: 10.1007/BF01664884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]