ABSTRACT

Rearrangements or point mutations in the noncoding control region (NCCR) of BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) have been associated with higher viral loads and more pronounced organ pathology in immunocompromised patients. The respective alterations affect a multitude of transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) but consistently cause increased expression of the early viral gene region (EVGR) at the expense of late viral gene region (LVGR) expression. By mutating TFBS, we identified three phenotypic groups leading to strong, intermediate, or impaired EVGR expression and corresponding BKPyV replication. Unexpectedly, Sp1 TFBS mutants either activated or inhibited EVGR expression when located proximal to the LVGR (sp1-4) or the EVGR (sp1-2), respectively. We now demonstrate that the bidirectional balance of EVGR and LVGR expression is dependent on affinity, strand orientation, and the number of Sp1 sites. Swapping the LVGR-proximal high-affinity SP1-4 with the EVGR-proximal low-affinity SP1-2 in site strand flipping or inserting an additional SP1-2 site caused a rearranged NCCR phenotype of increased EVGR expression and faster BKPyV replication. The 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends revealed an imperfect symmetry between the EVGR- and LVGR-proximal parts of the NCCR, consisting of TATA and TATA-like elements, initiator elements, and downstream promoter elements. Mutation or deletion of the archetypal LVGR promoter, which is found in activated NCCR variants, abrogated LVGR expression, which could be restored by providing large T antigen (LTag) in trans. Thus, whereas Sp1 sites control the initial EVGR-LVGR expression balance, LTag expression can override inactivation of the LVGR promoter and acts as a key driver of LVGR expression independently of the Sp1 sites and core promoter elements.

IMPORTANCE Polyomaviridae currently comprise more than 70 members, including 13 human polyomaviruses (PyVs), all of which share a bidirectional genome organization mediated by the NCCR, which determines species and host cell specificity, persistence, replication, and virulence. Here, we demonstrate that the BKPyV NCCR is fine-tuned by an imperfect symmetry of core promoter elements centered around TATA and TATA-like sequences close to the EVGR and LVGR, respectively, which are governed by the directionality and affinity of two Sp1 sites. The data indicated that the BKPyV NCCR is poised toward EVGR expression, which can be readily unlatched by a simple switch affecting Sp1 binding. The resulting LTag, which is the major EVGR protein, drives viral genome replication, renders subsequent LVGR expression independently of archetypal promoter elements, and can overcome enhancer/promoter mutations and deletions. The data are pivotal for understanding how human PyV NCCRs mediate secondary host cell specificity, reactivation, and virulence in their natural hosts.

INTRODUCTION

The Polyomaviridae comprise more than 70 polyomavirus (PyV) members, including at least 13 human PyV (HPyV) species (1). HPyV seroprevalence data obtained using the major capsid protein Vp1 as pentamers or virus-like particles indicate that HPyVs infect 50% to 90% of the general human population without known specific signs or symptoms of disease (2–7). As information about the virology and pathology of the 13 human PyVs is only emerging (8, 9), we focused on BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) as a model (10). After primary infection in early childhood, BKPyV persists latently in the renourinary tract with periods of low-level shedding into urine (4, 11, 12). Immunosuppression, which is commonly administered posttransplantation, has been shown to relax the adaptive antiviral immune control (13–16) and to permit high-level replication with median urine BKPyV loads of over 7 log10 copies/ml that become apparent as decoy cell shedding in urine (15–20). Progression to BKPyV disease is most consistently encountered as nephropathy in 1 to 15% of kidney transplant recipients (21–23) or as hemorrhagic cystitis in 5 to 20% of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients (24–26).

BKPyV disease involves viral genotypes indistinguishable from those of archetype BKPyV strains shed asymptomatically in the urine of healthy individuals (27–29), arguing that impaired adaptive immune control is necessary and sufficient. However, immunosuppressive drug-specific effects (20, 30) and viral determinants (31, 32) may also contribute to the evolution, kinetics, and severity of disease. At the core of what distinguishes archetype BKPyV strains with a low replicative capacity from the highly replicative strains found in kidney transplant patients are changes in the noncoding control region (NCCR) of the BKPyV genome (33). Akin to all PyVs, the BKPyV NCCR consists of an approximately 400-bp-long sequence which is sandwiched between the early viral gene region (EVGR) and the late viral gene region (LVGR), altogether yielding the double-stranded BKPyV DNA genome of 5,100 bp (34, 35). The NCCR contains cis-acting elements coordinating the timing and consecutive steps of EVGR expression, viral genome replication, and LVGR expression (33, 36).

The archetype BKPyV (ww) found in the urine of healthy immunocompetent individuals (29, 37, 38) is defined by a linear ww-NCCR sequence architecture arbitrarily denoted O143, P68, Q39, R63, and S63 (where the subscript numbers represent the number of nucleotides), which conveys rather slow replication in primary human renal tubular epithelial and urothelial cells (31, 39). In contrast, rearranged NCCRs (rr-NCCRs) associated with high blood viral loads and severe renal allograft pathology carry partial duplications and/or deletions of the archetype ww-NCCR sequence and give rise to virus strains with elevated levels of EVGR expression, faster viral replication, and more pronounced cytopathic effects in cell culture (31, 32, 40).

Although practically all emerging rr-NCCR BKPyV variants appear as unique sequences, we noted some common themes. These consist of an unaltered EVGR-proximal region covering the O143 block with the origin of replication and the central P68 block. Insertion strains carry complete or partial duplications of the P68 block, while deletion strains are characterized by the absence of the LVGR-proximal Q39 and R63 blocks and, rarely, the S63 block (31, 32, 40, 41).

In a detailed point mutational analysis in which more than 28 different transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) were inactivated without altering the overall archetype ww-NCCR architecture and length, we identified a hierarchy of TFBS resulting in three phenotypic groups: group 1 TFBS mutations resulted in EVGR activation at the expense of LVGR expression and fast replication rates, similar to the findings for clinical rr-NCCR variants. Group 2 TFBS mutations showed an intermediate phenotype with respect to EVGR expression and replication rates, whereas group 3 TFBS mutations reduced both EVGR and LVGR expression and permitted little or no viral replication (32).

Among the various factors, Sp1 appeared to have an outstanding role, since the BKPyV NCCR contained at least three Sp1 sites, two of which appeared to have fundamentally different effects on BKPyV expression and replication. Whereas inactivation of the SP1-4 site proximal to the LVGR resulted in strong EVGR expression, inactivation of the SP1-2 site proximal to the EVGR abrogated both EVGR and LVGR expression. This effect of the inactivating sp1-2 mutant also overrode group 1 activation, including the one seen with the sp1-4 mutant, suggesting a key role of Sp1 in the functionality of the NCCR as a whole.

In the present study, we investigated the role of these two key Sp1 sites and their relationship to core promoter elements in greater detail. Our results demonstrate that the BKPyV NCCR is fine-tuned by an imperfect symmetry of two core promoters with TATA and TATA-like elements at the EVGR and the LVGR, respectively. The bidirectional EVGR and LVGR expression is governed by the host cell transcription factor Sp1 and involves both DNA strand directionality and binding affinity. The data indicate that the BKPyV NCCR is poised toward EVGR expression, which can be readily discharged by a simple switch in Sp1 binding. The large T antigen (LTag), which is the major EVGR protein product, then drives genome replication and subsequent LVGR expression independently of Sp1 and TATA-like elements, thereby being able to overcome a range of deletions seen in the LVGR promoter of natural BKPyV variants. We discuss the implications of our results as a model for the novel human PyVs and the control of bidirectional gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human primary renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTECs; PCS-400-010; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in epithelial cell medium (EpiCM; catalog number 4101; ScienCell Research Laboratory, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with epithelial cell growth supplement (EpiCGS; catalog number 4152; ScienCell Research Laboratory, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; catalog number 0010; ScienCell Research Laboratory, Carlsbad, CA, USA). HEK293 cells (CRL1573; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), HEK293T cells (CRL3216; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and HEK293TT cells (catalog number 0508000; NCI-Frederick Repository Service, Frederick, MD, USA) were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), high-glucose formulation (DMEM-H; catalog number D5671; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), containing 8% FBS (catalog number S0113; Biochrome AG, Berlin, Germany). Medium for cultivation of HEK293TT cells was supplemented with 400 μg/ml hygromycin B (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA). COS-7 cells (CRL1651; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in DMEM-H, containing 5% FBS. All cultures were supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine (catalog number K0302; Biochrome AG, Berlin, Germany).

FACS-based, bidirectional reporter assay.

The bidirectional reporter construct used to measure expression of the early (red fluorescent protein [RFP]) and late (green fluorescent protein [GFP]) virus gene regions has been described before (31). Furthermore, we described a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS)-based quantification method for this reporter construct (32). While the use of flow cytometry for the reporter assay enables a convenient means of visualization of expression, at the same time, accurate and reproducible quantification is achieved. In particular, the gating for the same number of transfected cells from each sample as a method of normalization overcomes the problem of different transfection efficiencies between different plasmid preparations, mutants, or cell lines. HEK293, HEK293T, or HEK293TT cells were seeded in 12-well plates and transfected at 70 to 80% confluence with the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (catalog number 11668-019; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a ratio of 3:1 (3 μl reagent, 1 μg plasmid DNA) in Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Medium was replaced with DMEM-H–10% FBS on the next morning. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were rinsed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–2.5 mM EDTA and then detached, suspended, and transferred to 5-ml polystyrene round-bottom FACS tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with DMEM (without phenol red) and 1% fetal calf serum (FCS). Directly before each measurement, DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; catalog number D8417; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added (final concentration, 1 ng/ml) as a dead cell marker, and the cells were resuspended. FACS measurements were carried out on a Fortessa cytometer (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). For GFP, excitation was at 488 nm (blue laser) and emission was at 530/30 nm; for RFP, excitation was at 561 nm (yellow-green laser) and emission was at 586/15 nm; and for DAPI, excitation was at 405 nm (violet laser) emission was at 450/50 nm. In order to calculate the weighted mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for red (early) and green (late) expression, the cell number (N) and mean fluorescence (I) of quadrants Q1 (red cells), Q2 (red and green cells), and Q4 (green cells) were inserted into the following formulas: MFI (red) = [(NQ1 · IQ1) + (NQ2 · IQ2)]/(NQ1 + NQ2 + NQ4) and MFI (green) = [(NQ2 · IQ2) + (NQ4 · IQ4)]/(NQ1 + NQ2 + NQ4).

The early expression of all constructs was normalized to that of the Dunlop strain (set as 100%), and late expression was normalized to that of the archetype ww(1.4) strain (set as 100%). The mean values and standard deviations were calculated with GraphPad Prism software (version 6 for Mac OS).

EMSA.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis of TFBS was performed as described previously (42). Briefly, 10 μg of nuclear extract from RPTECs was mixed with binding buffer (20 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)], pH 6.8; 50 mM NaCl; 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]; 0.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin; 100 μM ZnSO4; 0.05% NP-40; 4% Ficoll) and approximately 5 fmol of 32P-labeled, duplexed oligonucleotide in a final volume of 20 μl. The oligonucleotides with the SP1-2 and SP1-4 binding sites were described before (32). Nuclear extracts were prepared as described by Schreiber et al. (43) by scraping cells with ice-cold PBS off 10-cm dishes and collecting them in Eppendorf tubes. After centrifugation they were swollen in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9; 10 mM KCl; 0.1 mM EDTA; 2.5 mM DTT) and lysed by addition of NP-40 (final concentration, 0.5%). After centrifugation of the nuclei, proteins were extracted in nuclear extract buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9; 25% glycerol; 400 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 2.5 mM DTT). Competing, unlabeled oligonucleotides were used as described in the legend to Fig. 2. After incubating the mixture on ice for 30 min, samples were separated on a native 4% polyacrylamide gel with 0.25× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) as the running buffer. The detection of β decay was carried out with a Fujifilm FLA-7000 image plate reader.

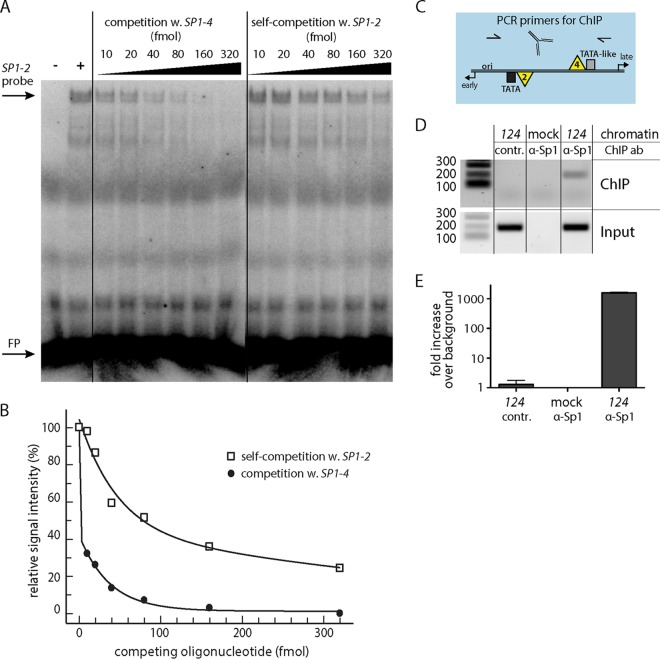

FIG 2.

SP1-2 and SP1-4 differ in Sp1 affinity in EMSA competition assays. (A) Representative EMSA result after competition of the radiolabeled SP1-2 probe with (w.) unlabeled SP1-4 or unlabeled SP1-2 (self-competition) at the indicated concentrations. Lane −, binding mix without nuclear extract; lane +, binding mix without competition; FP, free probe. (B) Plot of quantitative readout of EMSA signals. x axis, concentration of competing oligonucleotide; y axis, signal strength relative to that of the uncompeted SP1-2 signal, set to 100%. (C) Scheme of NCCR with primer binding sites for ChIP assay. (D) Semiquantitative analysis of ChIP assay results by agarose gel electrophoresis. Mock, untransfected HEK293TT cells; contr., ChIP with rabbit negative-control antibody (ab) supplied with the kit. Numbers on the left are denote DNA fragment sizes (in base pairs). (E) Quantification of ChIP assay result by qPCR with SYBR green. Calculation was carried out by ΔΔCT method (with normalization to the ww-NCCR input and the background control).

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Magnify chromatin immunoprecipitation system; Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Science). Briefly, HEK293TT cells were transfected in 10-cm dishes with the BKPyV ww reporter construct and incubated for 48 h. The chromatin was cross-linked directly in the dish for 10 min with 10% formaldehyde. The cross-linking was quenched with 0.5 M glycine solution. Cells were harvested with ice-cold PBS, collected by centrifugation, and lysed. For the chromatin fragmentation, lysates were treated with micrococcal nuclease (20 min at 37°C; NEB) and sonicated with 30 cycles of 30-s pulses and 30 s of cooling in between each pulse (Sonicator Q700; QSonica). The ChIP antibodies were Sp1 D4C3 (ChIP-validated rabbit monoclonal antibody; Cell Signaling) (44) and a rabbit control antibody included with the kit. For PCR analysis by HotStar Taq (Qiagen) and a quantitative PCR (qPCR) SYBR green assay (PowerUp SYBR green; Thermo Fisher Scientific), the following primers were validated and used: primer NCCR-f (TCAGAAAAAGCCTCCACACC) and primer NCCR-r (CTTTGGCCAGTTTCCACTTC). qPCR data were analyzed by the ΔΔCT threshold cycle (CT) method as described before using ww-NCCR input and background control ChIP for normalization.

5′ RACE analysis of early and late transcripts.

To characterize the 5′ ends of viral transcripts and, hence, to identify the transcription start sites, we performed 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) procedures according to the manufacturer's instructions (5′ RACE system for rapid amplification of cDNA ends; Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, we isolated total RNA from RPTECs (RNeasy minikit; Qiagen) which were infected with either archetype virus or the Dunlop strain and reverse transcribed the mRNA by using a mixture of random hexamers and oligo(dT) primers (SuperScript II; Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific). The resulting cDNAs of viral origin were specifically amplified by using the following gene-specific primers (GSP): sTag-GSP1 (5′-AAGGGCAGTGCACAGAAG-3′), sTag/LTag (5′-AATCAGGCTGATGAGCTACC-3′), LTag-GSP1 (5′-TCTTCAGGCTCTTCTGG-3′), LTag-GSP2 (5′-TGGTGTKGAGTGTTGAGA-3′), agno-GSP1 (5′-TACAGCAGGTAAAGCAGTG-3′), agno-GSP2 (5′-TCCCGTCTACACTGTCTT-3′), VP2-GSP1 (5′-TGATAGAGGCCTACAGTG-3′), VP1-GSP1 (5′-AAGGCCTCTCCACTGTTG-3′), and VP1-GSP2 (5′-CCAGCACTCAACTGGATAAG-3′).

In silico analysis of the BKPyV NCCR.

To search for potential transcription factor binding sites within the BKPyV NCCR and to evaluate the effect of mutations on the binding sites, we used the MatInspector software tool (Genomatix, Munich, Germany). Additionally, to analyze the presence of core promoter elements, we used the search tool ElemeNT (http://lifefaculty.biu.ac.il/gershon-tamar/index.php/resources) (45).

Transfection of BKPyV genome into COS-7 cells and infection of RPTECs.

Transfection of BKPyV genomes into cells was initiated by cutting BKPyV plasmid DNA with BamHI and religating the diluted DNA as described previously (46). Transfection of religated BKPyV genomic DNA into COS-7 cells was performed when the cells were at 90 to 95% confluence in 6-well plates using Lipofectamine 2000 (catalog number 11668-019; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a reagent/DNA ratio of 3:1 according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 6 h after transfection, the medium was replaced with DMEM-H containing 5% FCS. At 7 days posttransfection, COS-7 cell supernatants were harvested and the number of DNase-protected genomic equivalents (GEq) per milliliter was quantified by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (see the next paragraph). For the infection of RPTECs with COS-7 cell supernatants, cells were seeded at 75,000 cells per well of a 24-well plate in 0.5 ml of supplemented EpiCM. After 24 h, when the cells were at a confluence of approximately 50%, RPTECs were exposed to 200 μl of the corresponding virus preparations adjusted to 2 × 107 GEq for each construct at 37°C for 2 h, followed by removal, washing, and replacement with EpiCM supplemented with 0.5% FCS.

BKPyV viral loads by real-time PCR.

BKPyV loads were quantified after DNA extraction from 200-μl cell culture supernatants with a QIAamp DNA blood minikit (Qiagen, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland). The real-time PCR protocol for detection of BKPyV DNA samples targets the BKPyV large T antigen-coding sequence and has been described before (47).

Western blotting.

Lysis of HEK293, HEK293T, and HEK293TT cells was done in NP-40 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 1% NP-40; 1× protease inhibitors [Roche]). Equal volumes of cell lysates, adjusted to 10 μg total protein, were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred onto a 0.45-μm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (catalog number IPFL00010; Millipore/Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The membrane was blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer (catalog number 927-40000; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) diluted 1:2 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). The membrane was then incubated with the following primary antibodies: polyclonal rabbit anti-LTag (1:10,000; C. H. Rinaldo, University of North Norway, Tromsø, Norway) and monoclonal mouse antiactin (1:5,000; Abcam, Cambridge, England) in Odyssey blocking buffer. After washing 5 times with TBS–0.1% Tween 20, the membrane was incubated in the following secondary antibodies: goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibody conjugated with IRDye 800CW (1:10,000; catalog number 926-32211; LI-COR) and donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 680 (1:15,000; catalog number A10038; Invitrogen). Protein detection and quantification were done with a LI-COR Odyssey CLx system.

RESULTS

Swapping of Sp1 sites within the NCCR causes rearrangement-like activation of EVGR expression.

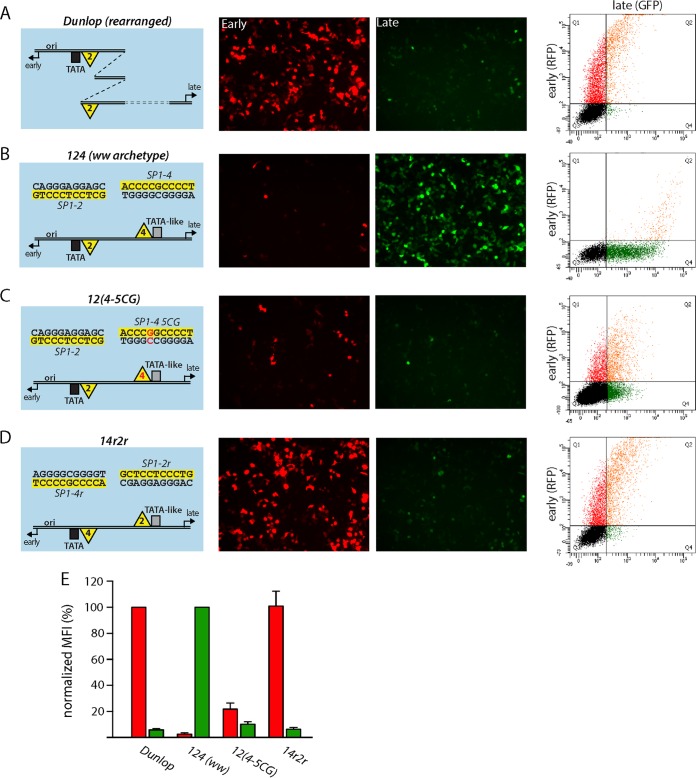

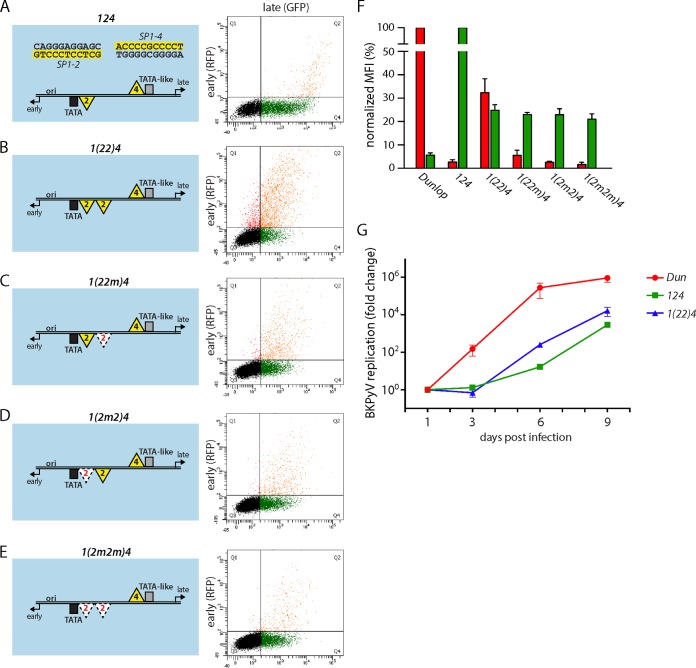

To measure the early and late promoter activity of the BKPyV NCCR, we transfected a bidirectional reporter construct into human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells, which allows monitoring of EVGR expression by the red fluorescence of DsRed and monitoring of LVGR expression by the green fluorescence of enhanced green fluorescent protein (31, 32). Using this reporter assay, the strain Dunlop NCCR, as a representative of rr-NCCRs bearing duplications and deletions, showed strong EVGR expression (red) but only a low level of LVGR expression (green) (Fig. 1A). The Dunlop NCCR contains an intact SP1-2 site upstream of the TATA box but bears two incomplete duplications of the P block, adding one SP1-2 site at a more distant upstream location, while LVGR proximal sequences, including SP1-4, are deleted (Fig. 1A, left, with the yellow triangles labeled 2 indicating SP1-2). In contrast, the archetype BKPyV ww strain has all three Sp1 sites in the archetype position (ww-NCCR 124) and showed a low level of EVGR expression (red) but strong LVGR expression (green) (Fig. 1B, left, ww archetype NCCR 124, with the yellow triangles labeled 2 and 4 indicating SP1-2 and SP1-4, respectively). As reported previously (32), point mutations, like the naturally occurring SP1-4 variant 5CG (which has a C-to-G transition at position 5) from a patient with BKPyV-associated hemorrhagic cystitis (48), are sufficient to cause an activation of EVGR expression compared to the archetype ww-NCCR, at the expense of LVGR expression [NCCR 12(4-5CG) in Fig. 1C and E]. Given the striking effects of rather subtle Sp1 site mutations with respect to EVGR and LVGR expression (32), we investigated whether or not the different Sp1 sites might have different sequence-encoded properties. We noted that SP1-2 and SP1-4 have inverse orientations relative to one another, which is possible because Sp1 sites are composed of nonpalindromic sequences. In a first approach, the early SP1-2 site and the late SP1-4 site were simply swapped and placed in reverse orientation to maintain the archetypal strand orientation, yielding NCCR 14r2r (where the letters r indicate inverted SP1-4 and SP1-2 sequences, respectively) (Fig. 1D and E; the C-rich sequence of the EVGR-proximal Sp1 site and the C-rich sequence of the LVGR-proximal Sp1 site are highlighted in yellow). Compared to the archetype, NCCR 14r2r caused a strong increase of EVGR expression and decreased LVGR, similar to the phenotype produced by the rr-NCCR of the Dunlop strain (Fig. 1A, D, and E). Quantification using the mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) demonstrated that the increase in EVGR expression corresponded to 80 to 100% of the Dunlop NCCR signals (Fig. 1E). At the same time, the level of LVGR expression was reduced to about 10% of the archetype level. We concluded that maintenance of the Sp1 sites but simple swapping of SP1-2 and SP1-4 within the archetypal NCCR was sufficient to invert the bidirectional expression pattern of the archetype promoter/enhancer system.

FIG 1.

Swapping of SP1-2 and SP1-4 in the BKPyV NCCR affects early and late promoter activity similarly to major rearrangements. (A to D) (Left) Schematic representation of NCCRs tested with the FACS-based, bidirectional reporter assay. All NCCRs were cloned into the previously described reporter vector pHRG, in which RFP serves as a marker for early expression and GFP serves as a marker for late expression (31). The Gardner isolate-derived laboratory strain Dunlop is characterized by triplication of the P-block sequences and deletion of Q- and R-block sequences. The BKPyV archetype NCCR 124 is used as a reference. Horizontal black lines, double-stranded DNA of the NCCR; black box, conserved TATA box; gray box, TATA-like element; yellow triangles labeled 2, SP1-2 Sp1 transcription factor binding site; yellow triangles labeled 4, SP1-4 Sp1 transcription factor binding site; black number 4, Sp1-binding site with archetype sequence; red number 4, Sp1-binding site carrying one or more mutations; yellow highlight, the respective Sp1 upper-strand sequence with respect to the direction of early and late transcription (black arrows). (Middle two columns) The indicated NCCR reporter constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells, and fluorescence images for RFP (early) and GFP (late) expression were taken at 2 days posttransfection. (Right) Representative flow cytometry measurements of the indicated NCCRs. x axis, GFP fluorescence; y axis, RFP fluorescence. For each measurement, we gated for 5,000 transfected (fluorescent) cells in quadrants Q1, Q2, and Q4. (E) For quantification, the normalized MFI (in percent) was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Early expression was normalized to that of strain Dunlop (red MFI = 100%), and late expression was normalized to that of NCCR 124 (ww archetype) (green MFI = 100%). Quantification results are from at least 3 independent replicates.

The LVGR SP1-4 has a higher in vitro Sp1-binding affinity than the EVGR SP1-2.

Although Sp1 has been shown to bind to both SP1-2 and SP1-4 in vitro (32), there are differences in the respective sequence compositions. While SP1-4 represents a perfect Sp1 consensus sequence, SP1-2 carries deviations by A/T base pairs (Fig. 1B to D, sequences indicated in yellow). To examine whether the sequence differences were associated with different binding affinities, an EMSA-based competition assay was employed. 32P-radiolabeled, duplexed oligonucleotides carrying SP1-2 were incubated with nuclear extract from primary human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTECs) and mixed with increasing concentrations of unlabeled oligonucleotides containing SP1-2 or SP1-4 (Fig. 2A). As shown, competition with the unlabeled SP1-4 oligonucleotides decreased the EMSA signal more readily than competition with the unlabeled SP1-2 oligonucleotides: while 10 fmol of the SP1-4 oligonucleotide was enough to reduce the SP1-2 signal to about 30% of the signal for the archetype, self-competition required approximately 30 times higher competitor concentrations (Fig. 2B). This finding indicates that the SP1-4 binding site has a higher affinity for Sp1 binding than SP1-2, as expected from comparison of their sequences with the perfect Sp1 consensus sequence. Together, the combined data suggest that the affinity of Sp1 binding to the intact local SP1-2 and SP1-4 sites determined the higher activity of the LVGR promoter in the archetype ww-NCCR. To complement the in vitro data, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed in ww-NCCR reporter construct-transfected cells (Fig. 2C and D). ChIP with the Sp1 antibody yielded an enrichment of about 1,600-fold compared to that achieved with a control antibody, demonstrating the strong binding of Sp1 to the BKPyV NCCR in vivo (Fig. 2E).

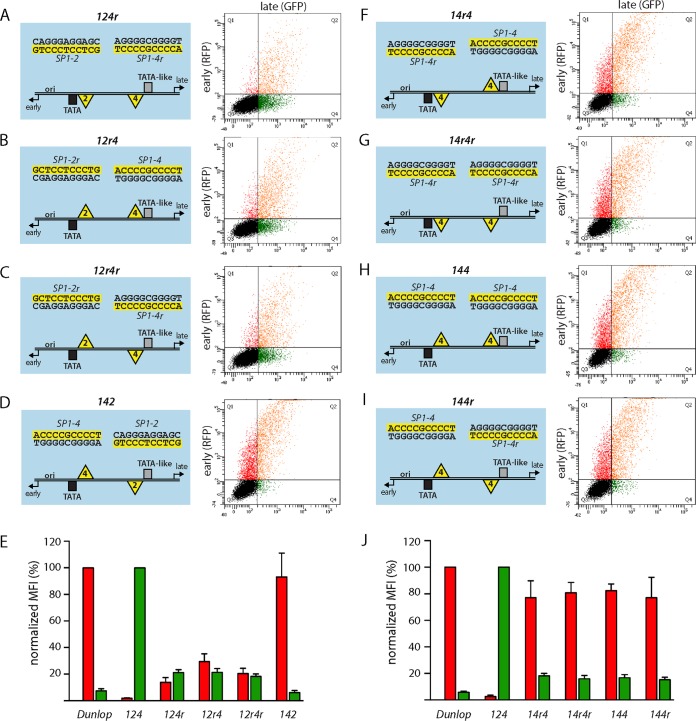

Strand inversion of Sp1 sites disrupts the archetype EVGR-LVGR expression balance.

To examine the potential contributions of the nonpalindromic Sp1 sites to the directionality of gene expression, SP1-2 and SP1-4 were flipped in place, yielding the NCCRs 124r, 12r4, and 12r4r, as well as swapped with respect to their original archetype position (NCCR 142) (Fig. 3A to D). All NCCR inversion mutants showed impaired LVGR expression with a reduction in the level of expression to about 20% of the archetype level. Of note, all of these constructs except 142 still carried an intact high-affinity SP1-4 site in the LVGR promoter region, including NCCR 12r4, in which SP1-4 was even maintained in its original strand orientation (Fig. 3B and E). At the same time, all inversion mutants showed a moderate level of EVGR activation compared to the archetype, whereby the NCCR 12r4 had the strongest expression in the range of 25% of the level seen for the Dunlop rr-NCCR. These observations indicate that the relative Sp1 site orientation was critical for regulating bidirectional expression, in addition to affinity. Importantly, the Sp1 sites were able to convey an orientation-dependent directionality that seemed to be functionally as important as the local Sp1-binding affinity or deletion of SP1-4. Interestingly, NCCR 142 yielded a high EVGR expression level similar to that of Dunlop and the initially tested 14r2r mutant (Fig. 3D and E and 1D and E). We concluded that, when placing the high-affinity SP1-4 site in the proximity of the EVGR, its orientation relative to the remaining NCCR did not matter anymore. This notion was further corroborated by another set of mutants, where the low-affinity SP1-2 was replaced with the high-affinity SP1-4, such that the EVGR and LVGR proximal positions contained Sp1 sites with equal affinities in all possible combinations of site orientations (Fig. 3F to J, NCCRs 14r4, 14r4r, 144, and 144r). All of the resulting mutants showed an equally high level of EVGR expression in the range of 80% of that of strain Dunlop, coupled to a profound loss of LVGR expression. Thus, a high-affinity Sp1 site in the proximity of the EVGR provided a strong activation, which in no case permitted rescue of the archetype expression pattern by an Sp1 site in an LVGR of similar sequence, affinity, or orientation (Fig. 3J). Conversely, the data further support the notion that the bidirectional fine-tuning of NCCR expression depends on the modulation of Sp1 affinity at the EVGR site.

FIG 3.

Position, orientation, and affinity of Sp1 sites determine the directionality of EVGR and LVGR expression. (A to D) (Left) Schematic representation of NCCRs tested with the FACS-based, bidirectional reporter assay in HEK293 cells. All mutant NCCRs have the length and architecture of the BKPyV archetype NCCR 124 but carry inverted Sp1 sites, as indicated with the letter r (e.g., NCCR 124r has an inverted SP1-4 sequence). (Right) Representative flow cytometry measurements are shown next to the schematic representations, which are described in the legend to Fig. 1. (E) Quantification of the constructs listed in panels A to D using the normalized MFI from at least 3 independent replicates, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (F to I) Schematic representation of NCCRs, where the archetype SP1-2 was replaced with the sequence of the high-affinity SP1-4. (J) Quantification of the constructs listed in panels F to I using the normalized MFI from at least 3 independent replicates, as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

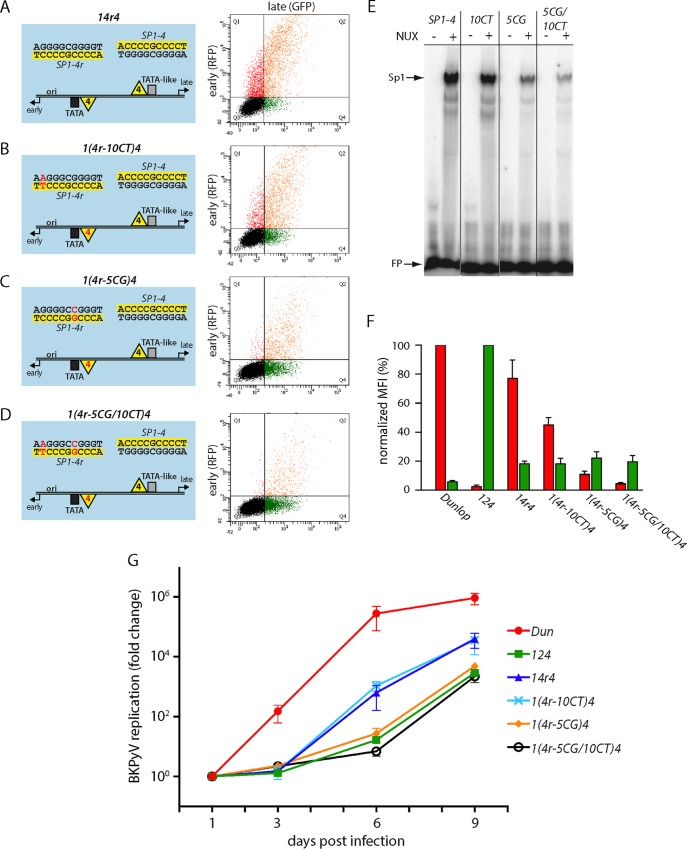

Early promoter activity correlates with the Sp1-binding affinity of the early Sp1 site.

To examine the role of Sp1 affinity in the critical EVGR position, the mutant 14r4 was used for further study by introducing point mutations that had been identified in patient variants (48) and previously shown by us to lower the Sp1-binding affinity (32). By slightly lowering the affinity of the EVGR-proximal Sp1 site with the mutant 1(4r-10CT)4 (where 10CT indicates the exchange of C to T in position 10), the expression of EVGR decreased to about half the level seen for mutant 14r4 (or 30 to 50% of that for the Dunlop reference strain) (Fig. 4B and F). The intermediate-affinity mutant 1(4r-5CG)4 allowed approximately 15% of the level of 14r4 EVGR expression (10% of that of Dunlop), while the double mutant showed only 5% of the level of expression by Dunlop (a >75% reduction compared to that for the 14r4 mutant) (Fig. 4C, D, and F). In contrast to the gradual decrease in the level of EVGR expression, the late promoter activity remained at the same low level (about 20% of the archetype level of expression). Hence, just lowering the affinity of the EVGR-proximal Sp1 site was not sufficient to restore a high level of LVGR expression. The data suggest that, in addition to affinity, particularities of the SP1-2 sequence might play a role for achieving a high level of LVGR activity.

FIG 4.

Lowering of the Sp1 affinity in the EVGR-proximal position of NCCR 14r4 reduces EVGR expression and viral replication. (A to D) Schematic representation (left) and representative FACS plot (right) of the indicated NCCRs tested in the bidirectional reporter assay in HEK293 cells. The numbering of the point mutants is relative to the first position of the SP1-4 site in the archetype orientation [e.g., NCCR 1(4r-10CT)4 contains the exchange of C to T in position 10, while the late SP1-4 site is unaltered]. (E) EMSA analysis of binding affinity in the absence and presence of nuclear extracts (NUX) confirms that the inserted point mutations lower the in vitro affinity of the respective variants. (F) Quantification of the constructs listed in panels A to D using the normalized MFI from at least 3 independent replicates, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (G) Mutant BKPyV replication in primary human RPTECs using infectious supernatants generated by transfection of COS-7 cells. The cell culture supernatants were taken at 1, 3, 6, and 9 days postinfection (x axis), and DNase-protected viral loads were quantified by qPCR. Results were normalized to the amount of input virus (day 1) and are shown as the fold change (y axis). Dun, strain Dunlop.

To confirm the mechanistic relevance of these findings, the NCCR mutants were placed into a BKPyV Dunlop backbone and analyzed in a viral replication assay. To minimize potential effects of EVGR expression and, hence, LTag levels, infectious supernatants were generated in COS-7 cells constitutively expressing simian virus 40 (SV40) LTag, as reported previously (32), and were used to infect RPTECs. Supernatants from RPTECs were then taken at 1, 3, 6, and 9 days postinfection (dpi), and viral loads were quantified by qPCR (Fig. 4G). As expected, the Dunlop strain had the highest replication rate of the tested strains, reaching supernatant viral loads of more than 1010 genome equivalents (GEq)/ml at 6 dpi, which corresponded to a more than 200,000-fold increase compared to the input (1 dpi). Importantly, the recombinant virus strains 14r4 and 1(4r-10CT)4 were functional and showed accelerated replication compared to that of the archetype virus, reaching levels of replication 1,000-fold that of the archetype virus at 6 dpi and about 40,000-fold that of the archetype virus at 9 dpi, respectively. However, the weakened affinity in the 1(4r-10CT)4 strain seen in the reporter assay did not translate into measurable differences in replication kinetics, suggesting that the EVGR-proximal Sp1 affinity was still strong enough to drive EVGR expression in the context of viral infection in cell culture. In contrast, the viruses carrying the stronger mutations 1(4r-5CG)4 and 1(4r-5CG/10CT)4 did not seem to allow rapid viral replication (Fig. 4G). Thus, the data indicate that the Sp1 affinity of the EVGR-proximal site was also reflected in the level of BKPyV replication, although the infection assay did not achieve the same nuanced resolution observed by the flow cytometry assay interrogating the bidirectional reporter constructs.

EVGR expression can be enhanced by low-affinity Sp1 site duplication.

Given the frequently observed duplications in the vicinity of the EVGR of rearranged NCCRs, including one of the NCCRs of the Dunlop strain, we examined expression in another set of NCCR mutants which carried a second SP1-2 site in the EVGR-proximal position, NCCR 1(22)4 (Fig. 5A and B). This additional binding site was sufficient to increase the level of EVGR expression 15-fold compared to that for the archetype, reaching about 30% of the level for Dunlop (Fig. 5F). To exclude a potential distance or length effect, we also examined inactivated Sp1 sites yielding the NCCRs 1(22m)4, 1(2m2)4, and 1(2m2m)4, in which the proximal SP1-2 site, the distal SP1-2 site, or both SP1-2 sites were mutated to sequences that no longer bound Sp1 (Fig. 5C, D, and E). These additional NCCR mutants showed reduced EVGR expression compared to the 1(22)4 mutant, in line with the notion that Sp1 binding and not any inserted sequence mediated an elevated level of EVGR expression. Together, these findings confirm that SP1-2 duplications found in parts of the P block of some patient isolates (31) as well as the Dunlop strain contribute to activation of the EVGR phenotype. Interestingly, all the experimentally designed insertions of the low-affinity SP1-2 diminished LVGR expression to a similar degree, again suggesting that some additional factors in the NCCR sequence might play a role. In the viral replication assay, recombinant BKPyV bearing NCCR 1(22)4 propagated slightly faster than the archetype NCCR 124 virus, which is in line with the results of the bidirectional reporter assay (Fig. 5G).

FIG 5.

Addition of a second low-affinity SP1-2 site increases the level of EVGR expression. (A to E) The indicated mutant NCCRs inserted into the bidirectional reporter constructs (left) were transfected into HEK293 cells, and representative FACS plots are shown (right). (F) Quantification of the constructs listed in panels A to E using the normalized MFI from at least 3 independent replicates, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Note that the y axis was divided for better visibility of the low range. (G) Mutant BKPyV replication in primary human RPTECs using infectious supernatants generated by transfection of COS-7 cells. Cell culture supernatant was taken at 1, 3, 6, and 9 days postinfection (x axis), and DNase-protected viral loads were quantified by qPCR. Results were normalized to the amount of input virus (day 1) and are shown as the fold change (y axis).

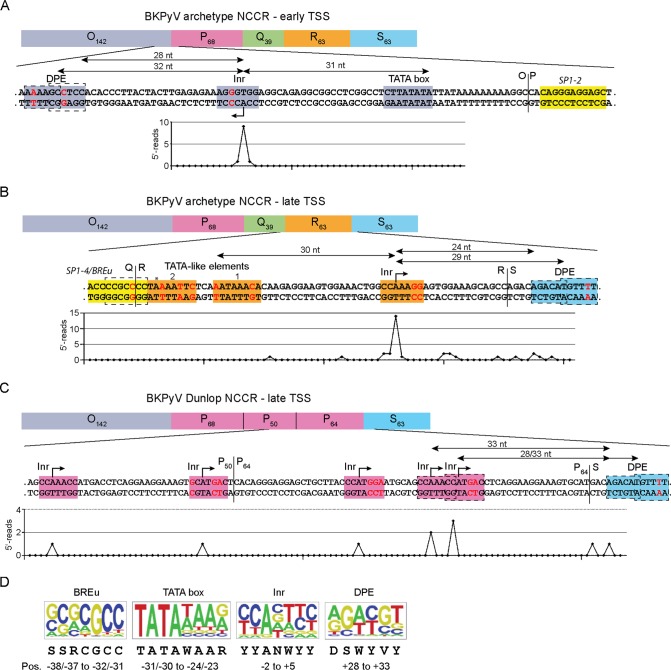

Characterizing the early and late core promoter elements of the archetype NCCR.

Given the strong effects of Sp1 sites on EVGR and LVGR expression through position, orientation, and affinity, we addressed potential cooperating components in their close proximity. Analysis of the NCCR sequence in the vicinity of the SP1-2 and the SP1-4 sites identified a canonical TATA box upstream of the EVGR start codon but only potential TATA-like elements upstream of the LVGR start codon which deviated from a perfect TATA box by several mismatches (49). The actual transcriptional start site (TSS) for the BKPyV NCCR EVGR was derived by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) analysis (Fig. 6A), which also revealed a sequence consistent with loci of initiator elements (Inr) (Fig. 6A). The positions of the Inr elements allowed the deduction of other core promoter elements (CPEs), which were located within the canonical distances upstream and downstream of the identified TSSs. The web-based search tool ElemeNT (45) confirmed the position of the early core promoter, which is located close to the O-block-P-block boundary and which is defined by the conserved TATA box and by a prominent Inr 31 bp downstream (Fig. 6A). In addition, a downstream promoter element (DPE) was identified at the typical distance of 28 to 32 nucleotides downstream from the Inr TSS. When the LVGR promoter region of the archetype NCCR was analyzed, a similar composition with a dominant Inr and potential DPEs was found (Fig. 6B), but in contrast to the EVGR promoter with its conserved TATA box, two potential TATA-like elements were located upstream of the Inr/major TSS (Fig. 6B, plot below the sequence). Of note, this major TSS was in line with a previous mapping of the BKPyV late promoter by a primer extension assay (50). One of the TATA-like elements had two mismatches compared to the sequence of a perfect TATA box but showed the canonical distance of 30 nucleotides to the major TSS (TATA-like element 1; Fig. 6B), while the other had three mismatches and was located further upstream (TATA-like element 2). An additional potential CPE was identified as a transcription factor IIB (TFIIB) recognition element upstream (BREu), which is typically located directly upstream of a TATA box. Thereby, the promoter elements of EVGR and LVGR presented an imperfect symmetry of a classical TATA and a TATA-like promoter. Interestingly, in the case of the LVGR promoter, the BREu was adjacent to TATA-like element 2 and consisted of a GC-rich consensus sequence which partially overlapped SP1-4 (Fig. 6B and D). This overlap of the LVGR BREu and high-affinity SP1-4 raised intriguing questions about the functional implications with respect to the regulation of LVGR expression through high-affinity Sp1 binding. It was therefore of interest to first examine deletion-bearing rr-NCCRs. As shown in Fig. 6C, the Dunlop rr-NCCR is characterized by a deletion of the Q35 and R63 blocks, which removes the TATA-like elements as well as SP1-4, and the dominant Inr, thereby disrupting the aforementioned imperfect symmetry of the late and the early sides of the archetype NCCR. The 5′-RACE analysis of the strain Dunlop NCCR revealed an overall dispersion of TSS but a slight overrepresentation of TSS at two potential Inr elements located in a canonical distance to the DPEs of 28 to 33 nucleotides (Fig. 6C, plot below the sequence). The results indicate that the loss of the LVGR CPEs could be partially compensated for by multiple initiator elements, which were found to be located throughout the triplicate P-block sequences and which acted in conjunction with the conserved DPEs of the S block. Together, the data indicate that the basal expression pattern of the archetype BKPyV NCCR involved an imperfect symmetry centering around a TATA box and TATA-like elements, which are modulated by juxtaposed Sp1-binding sites. Disruption of this basal symmetry by LVGR-proximal deletions was compensated for by the next-best fitting of analogous sequences.

FIG 6.

Experimental and computational core promoter analysis indicates the imperfect symmetry of the BKPyV archetype NCCR. The arbitrary sequences of the O, P, Q, R, and S blocks of the NCCR are shown on top. Selected nucleotide sequences enlarged with core promoter elements (CPE) are highlighted in the color of the respective sequence block, except for Sp1 sites, which are highlighted in yellow. Inr, initiator element; DPE, downstream promoter element (sequence in the dashed box highlighted in blue); BREu, TFIIB recognition element upstream, overlapping (dashed box) with SP1-4 highlighted in yellow; red nucleotides, mismatches compared to the CPE consensus sequence; vertical black lines, sequence block boundaries; horizontal black lines, distance (in nucleotides [nt]) from CPEs; dashed boxes, overlapping CPEs. The plot below the sequence shows 5′-RACE data, used to determine the transcription start site (TSS), with each point corresponding to the base pair position in the sequence presented above and the y axis showing the number of 5′ reads for the respective position. (A) Analysis of early core promoter located at the O block-P block boundary. (B) Analysis of the archetype late core promoter in the Q, R, and S blocks. *, position with the known polymorphism A/G, with G introducing an additional mismatch into the TATA-like element. (C) Analysis of Dunlop late core promoter with deletions removing the Q and R blocks. (D) Relevant CPEs with sequence logos, the consensus sequence in the IUPAC ambiguity code, and the typical position (Pos.) relative to the TSS (position +1) (45). R, A/G; W, A/T; S, C/G; Y, C/T; V, A/C/G; N, any nucleotide.

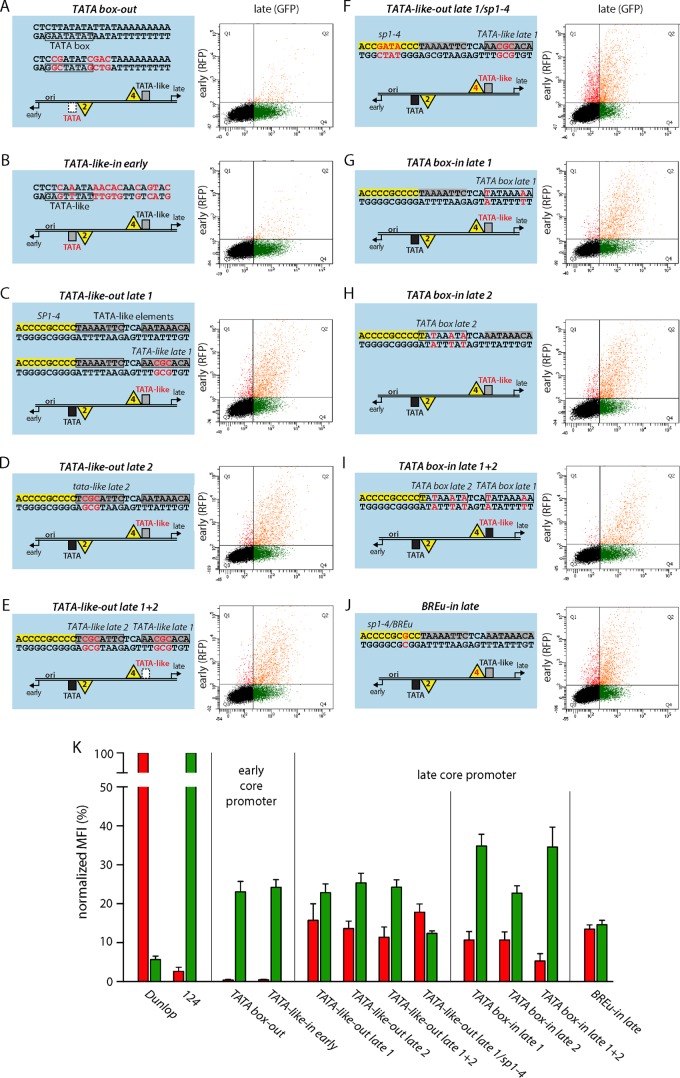

The TATA box is essential for both early and late expression.

To better understand the contribution of the respective core promoter elements for EVGR and LVGR expression, we designed a set of constructs in which we either removed defined sequence elements or changed them to obtain optimized consensus sequences but, again, without altering the overall length of the archetype NCCR. When we mutated the EVGR TATA box (Fig. 7A, TATA box-out, where “out” indicates that the CPEs were removed) or replaced it with a TATA-like element similar to the one at the LVGR (Fig. 7B, TATA-like-in early, where “in” indicates that the CPEs were inserted), not only was EVGR expression almost completely abolished but also LVGR expression was reduced to 23% of that of the archetype NCCR (Fig. 7K). These observations demonstrate the central importance of the TATA box not only for EVGR but also for the NCCR as a whole. In contrast, mutating the LVGR TATA-like elements individually or together (Fig. 7C to E, TATA-like-out late 1, TATA-like-out late 2, and TATA-like-out late 1 + 2) caused an increase in the level of EVGR expression to 10 to 15% of that of the archetype, while the level of LVGR expression was reduced to 20 to 25% of that of the archetype (Fig. 7K). Thus, effective LVGR expression from the late core promoter seemed to be equally dependent on both TATA-like elements, although the TATA-like element 1 sequence better matched a perfect TATA box and was situated within the canonical distances to the major TSS (Fig. 6B). When we mutated SP1-4, in addition to TATA-like element 1 (Fig. 7F, TATA-like-out late 1/sp1-4), LVGR expression went down by another 10%, suggesting a cooperative effect of the TATA-like element and the Sp1-binding site on the late promoter activity (Fig. 7K). Interestingly, changing the TATA-like elements individually or together to perfect TATA boxes did not increase the level of LVGR expression compared to that of the archetype NCCR (Fig. 7G to I, TATA box-in late 1, TATA box-in late 2, and TATA box-in late 1 + 2). Instead, the distance to the major Inr seemed to gain importance when a perfect TATA box sequence was inserted into the position of TATA-like element 1, as the level of LVGR expression then reached 35% of that of the archetype, while that of the corresponding construct with the TATA box-in late 2 reached only 23% of that of the archetype (Fig. 7K). Hence, the insertion of consensus TATA boxes in both positions diminished the LVGR promoter activity compared to that of the archetype, but the canonical positioning of the TATA box could partly compensate for this adverse effect.The single insertions showed an activation of EVGR expression of about 5-fold compared to that of the archetype (11% of that of the Dunlop strain), and the double mutant TATA box-in late 1 + 2 showed EVGR expression in the range of 5% of that of Dunlop.

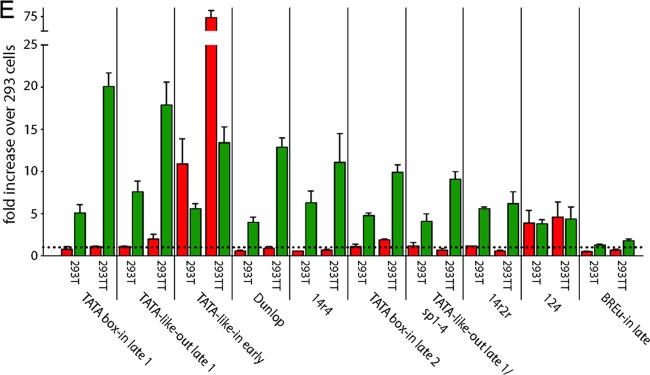

FIG 7.

Mutating the EVGR TATA box or the LVGR TATA-like elements increases early expression. (A to J) (Left) The indicated mutant NCCRs inserted into the bidirectional reporter constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells. Red letters, mutations compared to the archetype sequence. CPEs were either removed (indicated “out”) or inserted (indicated “in”). (Right) Representative FACS plots. (K) Quantification of the constructs listed in panels A to J using the normalized MFI from at least 3 independent replicates, as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

As mentioned above, the high-affinity SP1-4 overlaps a potential BREu. Both share a GC-rich consensus sequence, and the SP1-4 site carries only one mismatch compared to the sequence of a perfect BREu site (Fig. 6D). Therefore, a point mutation was introduced to create a perfect consensus BREu site (Fig. 7J, BREu-in late), which at the same time inactivated Sp1 binding, as shown for the previously analyzed SP1-4 point mutations (Fig. 1). The results show that introduction of a perfect BREu consensus site did not increase the level of LVGR expression but, rather, reduced it to a level of about 15% of that of the archetype. At the same time, EVGR expression was increased only moderately to about 14% of that of Dunlop or 7-fold of that of the archetype. This finding indicates that the SP1-4 site is more important than the potential BREu for driving LVGR expression.

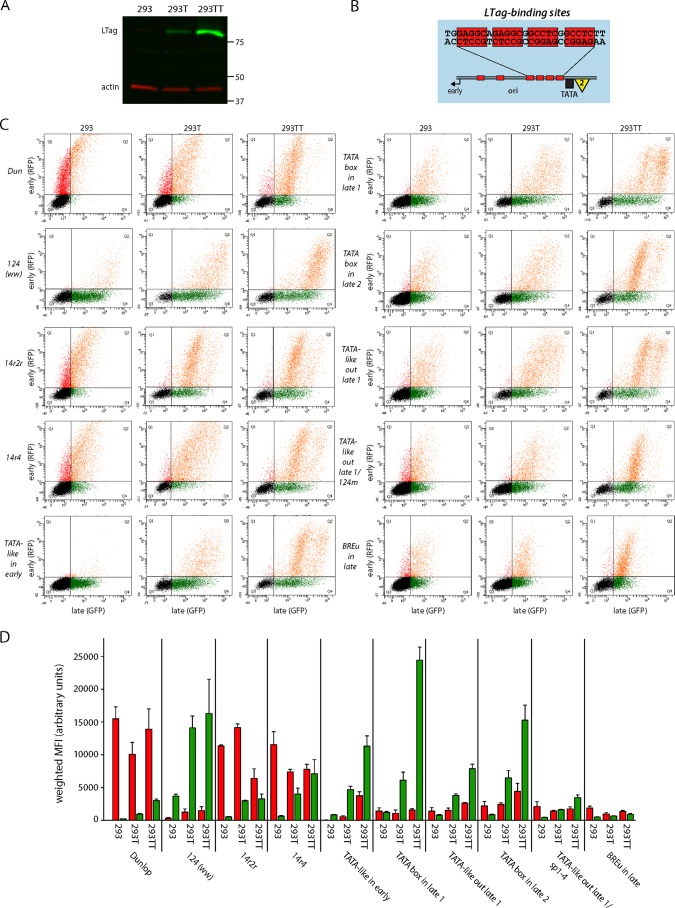

LTag can drive LVGR expression independently of archetypal late CPEs.

LTag is a major product of EVGR expression and an important regulator of the viral life cycle with respect to viral DNA replication and LVGR expression. We therefore compared the effects of critical NCCR mutants in HEK293, HEK293T, and HEK293TT cells, which produce no, small, or large amounts of SV40 LTag in trans, respectively (Fig. 8A). One essential function of LTag for the viral life cycle is to bind to the viral origin of replication (in the O block) and to facilitate, together with cellular factors, the replication of the viral genome (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, for almost all NCCR mutants tested, LTag was able to boost LVGR expression in a concentration-dependent manner. Despite variations in the absolute fluorescence intensities (Fig. 8C and D), most NCCR reporter constructs showed similar relative increases in the levels of LVGR expression in HEK293T and HEK293TT cells compared to the levels in their HEK293 cell counterparts (indicated by a dashed line, set to 1 for early and late fluorescence and each construct in HEK293 cells; Fig. 8E). The Dunlop strain, for example, which is characterized by a very low level of late expression in HEK293 cells, expressed 4 times more LVGR in HEK293T cells and 13 times more LVGR in HEK293TT cells than in HEK293 cells. At the same time, the level of EVGR expression of Dunlop stayed at the same level in the three cell lines. Since the LTag-mediated increase of LVGR expression was also observed with the Dunlop NCCR, which carries a large deletion of the archetypal late promoter elements (Fig. 6C), we concluded that LTag rendered LVGR expression independent of the expression of most archetypal late CPEs. This is in line with the finding that the TATA-like elements are dispensable, as observed with the construct TATA-like-out late 1, which showed an 8-fold increase in HEK293T cells and an 18-fold increase in HEK293TT cells compared with that in HEK293 cells. On the other hand, the highest absolute intensity (24,400 arbitrary units; Fig. 8D) and the highest relative increase (20-fold; Fig. 8E) in HEK293TT cells were recorded with the TATA box-in late 1 construct, which carried a perfect TATA box in a canonical distance to the major late Inr (Fig. 7G). We concluded that although the activating effect of LTag on LVGR expression could occur without the archetypal late promoter, there still seemed to be a benefit from the presence of a perfect TATA box and the high-affinity SP1-4 site. The latter becomes visible when the levels of expression in the constructs NCCR 14r2r and 14r4, both of which carry the high-affinity SP1-4 site in the early promoter but differ in the affinity of the late Sp1 site, are compared. While swapping of NCCR 14r2r increased the level of LVGR expression by only 6-fold in HEK293TT cells, LVGR expression of NCCR 14r4 was boosted by 11-fold. However, LVGR expression of the archetype NCCR 124 was already high in HEK293 cells, which explains why the absolute and relative increases in HEK293T and HEK293TT cells were only moderate (4-fold). Intriguingly, LTag activation of LVGR expression also worked in the absence of the otherwise essential and conserved TATA box when it was compared in the EVGR mutants TATA box-out (not shown) and TATA-like-in early (Fig. 8C to E). The only exception to this LTag-mediated increase in LVGR expression was in the mutant NCCR BREu-in late, where a point mutation in the high-affinity SP1-4 site created a perfect BREu site. Here, the increase in the level of LVGR expression was only 1.3-fold (HEK293T cells) and 1.8-fold (HEK293TT cells). Since both the SP1-4 mutant (not shown) and the double mutant TATA-like-out late 1/sp1-4 (Fig. 8E) were activated by LTag, we can only speculate at this point that the binding of TFIIB to the late promoter might pose an obstacle to LTag-mediated LVGR expression. Finally, we observed that EVGR expression remained similar for most constructs in this comparative transfection study, suggesting that the previously reported negative feedback of LTag on EVGR expression might be offset by increasing reporter construct replication. Notable exceptions to this observation were two constructs which had very low levels of EVGR expression in HEK293 cells, namely, the archetype NCCR 124 and the TATA box mutant TATA-like-in early. Here, few changes in early expression occurred, and these were probably attributable to plasmid copy number changes or an only subtle stimulation of the early promoter by LTag, which resulted in large relative increases in the expression levels.

FIG 8.

LTag expression in trans increases the level of LVGR expression in a concentration-dependent manner and can drive late expression independently of core promoter elements. (A) Western blot showing the different LTag expression levels by HEK293, HEK293T, and HEK293TT cells and the level of actin expression as a loading control. Numbers on the right are molecular masses (in kilodaltons). (B) Schematic view of LTag-binding sites (sequences with a red background) in the O block of the BKPyV NCCR. (C) Representative flow cytometry of HEK293, HEK293T, and HEK293TT cells transfected with the indicated BKPyV NCCR bidirectional reporter constructs. (D) For quantification of EVGR and LVGR expression in the transfected cells, the normalized MFI (in percent) was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. The level of EVGR expression was normalized to that of strain Dunlop (red MFI = 100%), and the level of LVGR expression was normalized to that of NCCR 124 (ww archetype) (green MFI = 100%). Quantification was based on at least 3 independent replicates. (E) Relative change in the levels of EVGR and LVGR expression by the indicated reporter constructs in HEK293T and HEK293TT cells using HEK293 cells as a reference (for which the level of expression was set equal to 1 and is indicated by a horizontal dashed line).

DISCUSSION

The NCCR determines within only 400 bp essential functions of PyV biology, including viral persistence and the appropriate timing of virus gene expression, genome replication, and virion assembly. Whereas other similarly sized viruses, like members of the Papillomaviridae or proviral copies of the Retroviridae, use unidirectional promoter organization, PyVs have effectively evolved a complex bidirectional expression modality to sequentially role out a strand- and orientation-specific set of virus gene products from their NCCRs. Notably, these steps of the PyV life cycle are host specific and, within a given host, restricted to certain cells, arguing that cellular differentiation and activation states must be readily sensed and interpreted by PyV-specific NCCRs.

As the archetype NCCR of BKPyV is stably maintained in the general population, we were intrigued by the rapid real-time emergence of BKPyV variants with rearranged NCCRs in immunosuppressed kidney transplant patients and their functional link to increased EVGR expression, accelerated viral replication, higher blood viral loads, and more advanced pathology (31). Given the diverse array of affected TFBS in the rr-NCCRs, we recently introduced defined point mutations that excluded the potential effects of overall length and architecture on NCCR function and identified three phenotypic groups of TFBS (32): group 1 and group 2 mutations caused a strong and an intermediate level of activation of EVGR expression and viral replication, respectively, similar to that caused by natural BKPyV NCCR variants associated with disease, whereas group 3 mutations permitted only reduced or no NCCR function (32). Importantly, Sp1 emerged as a key regulatory factor, being able to mediate either extreme of the group 1 mutant (e.g., SP1-4) or the group 3 mutant (e.g., SP1-2) phenotype.

In the present study, we demonstrate that Sp1 can exert these differential effects as a result of the position, orientation, and affinity of two Sp1 TFBS located on the LVGR- and the EVGR-proximal sides of the archetype NCCR. Swapping of the low-affinity SP1-2 site and high-affinity SP1-4 site (e.g., NCCR 14r2r), introducing affinity-lowering mutations into the high-affinity SP1-4 site [e.g., NCCR 12(4-5CG)], flipping the Sp1 site orientation (e.g., NCCR 124r), and creating various permutations and combinations thereof perturbed the EVGR-LVGR balance and in most cases led to a significant increase in the level of EVGR expression. In a key experiment, we made use of the construct NCCR 14r4, which carries the same high-affinity SP1-4 sequences in the respective EVGR- and LVGR-proximal positions, followed by introducing affinity-lowering mutations that caused a stepwise decline in the level of the activated EVGR phenotype. In another approach, the low-affinity SP1-2 site was duplicated, showing that two low-affinity Sp1 sites were better than one or none, overall supporting the role of local Sp1-binding affinity. Importantly, the mutant NCCRs were functional in recombinant BKPyVs, yielding elevated viral replication compared to that of archetype BKPyV in RPTECs, as predicted. Thus, the nonpalindromic nature of the Sp1-binding sequence and the deviations from its consensus sequence affected the directionality of expression and regulated the delicate EVGR-LVGR balance of the BKPyV archetype NCCR.

We also obtained evidence that the NCCR balance of the Sp1 sites acts in conjunction with core promoter elements (CPE), showing an imperfect rotation symmetry of a developmental promoter on the EVGR and a housekeeping promoter on the LVGR side of the BKPyV archetype NCCR. In general, most eukaryotic promoters can be assigned to (i) developmental or regulated promoters, which are characterized by a focused transcriptional start, that need to be activated by a stimulus and contain either a TATA box or a DPE and (ii) housekeeping or tissue-restricted promoters that are constitutively active and show multiple, dispersed transcriptional start sites, that are BREu enriched, typically without a TATA box, and that contain a CpG island (51, 52). Indeed, the EVGR side carries downstream of the Sp1 site a perfect TATA box and one major Inr/TSS in a canonical distance of 31 bp, followed by a consensus downstream promoter element (DPE) at a distance of 28 bp (53, 54). Thus, our results indicate that the EVGR promoter of the BKPyV archetype NCCR fulfills the criteria of a regulated promoter with a perfect TATA box, a focused TSS, and a low level of basal activity. The LVGR promoter is less easily classified, since it bears the high-affinity SP1-4 partially overlapping a potential BREu, followed by two TATA-like elements, a major Inr besides some dispersed TSS, and potential DPEs. We demonstrate here that the archetype BKPyV LVGR promoter shows a mixed focused-dispersed activity, which changes to a fully dispersed type of activity in the BKPyV Dunlop NCCR due to the deletion of the archetypal late promoter, extending the initial observation in hybrid NCCRs (50). The LVGR promoter is reminiscent of the previously described TATA-less housekeeping promoters described in the model of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which essentially contain TATA-like elements (49). It is currently unclear whether TATA-like elements bind TATA-binding protein (TBP). One hypothesis is that they do but, compared to the results obtained with perfect TATA boxes, that binding leads to the assembly of altered preinitiation complexes (PIC), which—at least in yeast—have been shown to be Taf1/TFIID enriched (49). Alternatively, these kinds of sequences might be binding sites for paralogs of TBP, like TRF2, thereby leading to differential PIC formation and transcriptional activity. Accordingly, the imperfect symmetry of Sp1 sites, TATA elements, Inr, and DPEs in the BKPyV NCCR seems to allow the maintenance of the archetypal focus on the LVGR side while repressing EVGR expression. At the same time, this organization permits an effective bidirectional system that is highly poised to shift the transcriptional balance from LVGR to EVGR expression upon differential stimulation and mutation (32). A summary model of our findings is depicted in Fig. 9. It should be noted that a second layer of regulation that involves BKPyV microRNAs (miRNAs) also governs the effective control of EVGR expression. These miRNAs are transcribed in the late direction and target the EVGR transcripts, thus mediating repression of LTag expression (55). Thereby, persistent archetype BKPyV infection maintains a double-stitched mechanism to ensure tight control of LTag expression below the radar of the immune system (55, 56). In turn, activating rearrangements not only switch on EVGR expression but also overcome miRNA suppression, an alteration that requires the absence of a functional immune response (31).

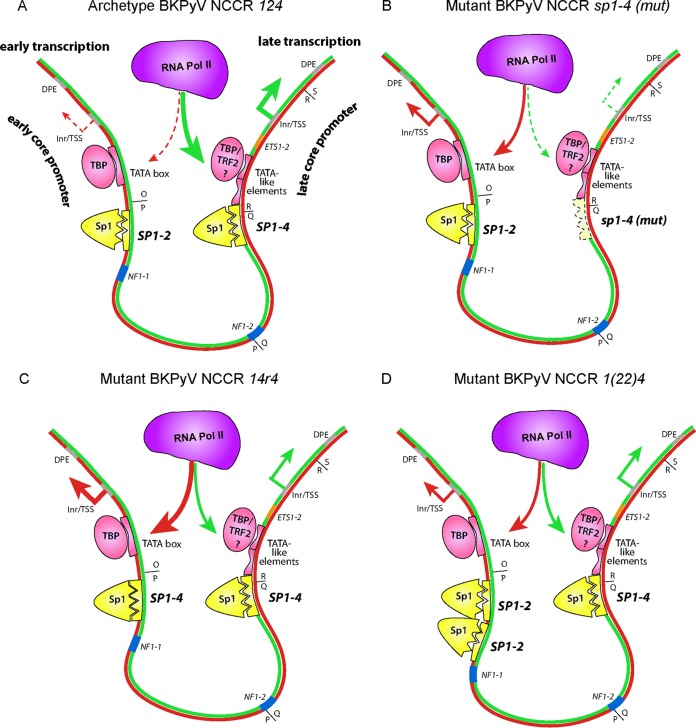

FIG 9.

Sp1, TATA, and downstream promoter element (DPE) core promoter elements forming an imperfect symmetry underlying bidirectional EVGR and LVGR expression of the BKPyV NCCR. (A) BKPyV archetype NCCR 124 predominantly drives LVGR expression as a result of the high-affinity SP1-4 (the three triangular indentations represent the zinc finger binding) and TATA-like elements, whereas EVGR expression is regulated by the low-affinity SP1-2 site (two triangular indentations) and the TATA box. The Sp1 protein is depicted in yellow, with the three small triangles symbolizing zinc fingers. Pink ovals depict TBP (TATA box-binding protein) or TRF2 (TBP-related factor 2), with the latter potentially being recruited by TATA-like elements. A low level of early expression is due to less efficient recruitment of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to the early promoter (red dashed arrows), and a high level of late transcription is due to recruitment of a major fraction of RNA polymerase II to the late promoter (fat green arrows). Inr, initiator element. For simplicity, other components, such as TFIIB and the TFIID complex or transcription factors like NF1, are not depicted (see reference 32). (B) Mutant BKPyV NCCR 124 carrying an SP1-4 sequence with a point mutation (mut) that abrogated Sp1 affinity and thereby the recruitment of polymerase II to the late promoter, leading to a decrease in the level of LVGR expression (green dashed arrows). The low-affinity SP1-2 now permits preferential recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the early promoter, causing increased levels of EVGR expression (red arrows). (C) Mutant BKPyV NCCR 14r4 in which the low-affinity SP1-2 sequence was replaced with a high-affinity SP1-4 sequence in the EVGR promoter. An increased fraction of RNA polymerase II is recruited to the early tandem of the TATA box and SP1-4, giving rise to high levels of EVGR expression (fat red arrows), while the unaltered late promoter is disfavored (green arrows). (D) Mutant BKPyV NCCR 1(22)4 carrying a duplication of the low-affinity SP1-2 site in the early promoter increases RNA polymerase II recruitment and EVGR expression (red arrows), while the unaltered late promoter is disfavored (green arrows).

The late DPEs located at the start of the S block are maintained in most patient isolates (31, 32), thus keeping the DPEs in place in rr-NCCR BKPyV variants lacking archetype late promoter sequences. Interestingly, these LVGR promoter deletions significantly increased EVGR expression at the expense of LVGR expression, but the associated increases in viral replication and progeny still depend on the corresponding expression of the LVGR structural gene products, e.g., Vp1, Vp2, and Vp3. We approached this issue by also providing two levels of SV40 LTag in trans in the HEK293 cell derivatives HEK293T and HEK293TT when transfecting selected NCCR mutants, thereby complementing the results of recombinant BKPyV infection in primary human RPTECs. The HEK293, HEK293T, and HEK293TT cell transfection experiments indicated that LTag expression in trans can overcome the adverse effects of deleting SP1-4 or the TATA-like elements in the LVGR promoter. These results are in line with those of a previous study reporting that the SV40 LTag is able to rescue a crippled promoter function which was lost due to the lack of a TBP-associated factor (TAF), TAF(II)250 (57). TAFs and TBP have been shown to form the TFIID complex and target the core promoter region by binding to DPEs, Inr, and TATA elements (52, 58). Our data suggest that LTag is able to activate the LVGR promoter by executing a TAF-like function within the TFIID complex, helping to recognize the remaining CPEs, namely, the DPEs of the S63 block and the dispersed Inr in the P68 block of the NCCR. As mentioned earlier, few mutants also showed an increase in the level of EVGR expression, suggesting a small contribution of LTag to early promoter activity and/or an increase in episomal plasmid copy number via ori-binding functions. The NCCR BREu-in late mutant was a notable exception with respect to LVGR activation, as it showed little change in its level of expression in HEK293T and HEK293TT cells, suggesting a possible negative interference with LTag-mediated activation. This mutation abrogated Sp1 binding, while it introduced a perfect consensus BREu, thus indicating that the SP1-4 site is more important than the potential BREu for driving LVGR expression.

This point mutational dissection of the bidirectional BKPyV NCCR may have implications for other HPyVs which show an architecture and an organization similar to those of BKPyV but which show a different TFBS composition and tissue specificity (59). In fact, NCCR rearrangements are best known from JC polyomavirus (JCPyV) variants from patient suffering from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (46, 60–62). Following duplication of the early promoter and deletion of the late promoter sequences, the JCPyV rr-NCCRs demonstrate activation of EVGR at the expense of LVGR similar to those of BKPyV (46). These alterations also broaden the host cell range, which has particular relevance for neurotropism and pathology (34, 63, 64). Given the power of the bidirectional reporter construct to predict PyV NCCR expression and viral replication, our approach may help to close the current knowledge gaps in viral host cell specificity and replication of the dozen novel human PyVs.

In conclusion, this study provides a novel view of the BKPyV NCCR by revealing an imperfect symmetry of the EVGR and LVGR promoter characteristics that are functionally balanced by the position, orientation, and affinity of Sp1 and core promoter elements. As there is currently no antiviral treatment available for BKPyV or the closely related JCPyV, this extended mechanistic understanding of the BKPyV NCCR might be utilized to design new therapeutic strategies targeting viral persistence and reactivation. Inhibition of EVGR promoter activation or the interaction of LTag with the LVGR promoter might open up the possibility of blocking viral infection while maintaining sufficient immunosuppression in transplant recipients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rainer Gosert, Julia Manzetti, Gunhild Unterstab, and Marion Wernli of the research group Transplantation & Clinical Virology in Basel, Switzerland, as well as Christine Hanssen Rinaldo from the University Hospital North Norway/Arctic University in Tromsø, Norway, for support and helpful discussions.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by an appointment grant of the University of Basel to Hans H. Hirsch. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Polyomaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, Calvignac-Spencer S, Feltkamp MC, Daugherty MD, Moens U, Ramqvist T, Johne R, Ehlers B. 2016. A taxonomy update for the family Polyomaviridae. Arch Virol 161:1739–1750. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2794-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeCaprio JA, Garcea RL. 2013. A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:264–276. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rinaldo CH, Hirsch HH. 2013. The human polyomaviruses: from orphans and mutants to patchwork family. APMIS 121:681–684. doi: 10.1111/apm.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kardas P, Leboeuf C, Hirsch HH. 2015. Optimizing JC and BK polyomavirus IgG testing for seroepidemiology and patient counseling. J Clin Virol 71:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.07.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kean JM, Rao S, Wang M, Garcea RL. 2009. Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000363. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gossai A, Waterboer T, Nelson HH, Michel A, Willhauck-Fleckenstein M, Farzan SF, Hoen AG, Christensen BC, Kelsey KT, Marsit CJ, Pawlita M, Karagas MR. 2016. Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses in a US population. Am J Epidemiol 183:61–69. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicol JT, Robinot R, Carpentier A, Carandina G, Mazzoni E, Tognon M, Touze A, Coursaget P. 2013. Age-specific seroprevalences of Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomaviruses 6, 7, and 9, and trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:363–368. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00438-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Dargel CA, van Vuren N, Hensbergen PJ, Feltkamp MC. 2015. Characterization of T antigens, including middle T and alternative T, expressed by the human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa. J Virol 89:9427–9439. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00911-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang SH, Wang R, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Knight SA, Buck CB, You J. 2016. The oncogenic small tumor antigen of Merkel cell polyomavirus is an iron-sulfur cluster protein that enhances viral DNA replication. J Virol 90:1544–1556. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02121-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai B, Qian M. 2010. Cellular entry of polyomaviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 343:177–194. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner SD, Field AM, Coleman DV, Hulme B. 1971. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. Lancet i:1253–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch HH, Steiger J. 2003. Polyomavirus BK. Lancet Infect Dis 3:611–623. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egli A, Kohli S, Dickenmann M, Hirsch HH. 2009. Inhibition of polyomavirus BK-specific T-cell responses by immunosuppressive drugs. Transplantation 88:1161–1168. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181bca422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binggeli S, Egli A, Schaub S, Binet I, Mayr M, Steiger J, Hirsch HH. 2007. Polyomavirus BK-specific cellular immune response to VP1 and large T-antigen in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 7:1131–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch HH, Knowles W, Dickenmann M, Passweg J, Klimkait T, Mihatsch MJ, Steiger J. 2002. Prospective study of polyomavirus type BK replication and nephropathy in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 347:488–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan DC, Agha I, Bohl DL, Schnitzler MA, Hardinger KL, Lockwood M, Torrence S, Schuessler R, Roby T, Gaudreault-Keener M, Storch GA. 2005. Incidence of BK with tacrolimus versus cyclosporine and impact of preemptive immunosuppression reduction. Am J Transplant 5:582–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randhawa P, Ho A, Shapiro R, Vats A, Swalsky P, Finkelstein S, Uhrmacher J, Weck K. 2004. Correlates of quantitative measurement of BK polyomavirus (BKV) DNA with clinical course of BKV infection in renal transplant patients. J Clin Microbiol 42:1176–1180. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1176-1180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginevri F, Azzi A, Hirsch HH, Basso S, Fontana I, Cioni M, Bodaghi S, Salotti V, Rinieri A, Botti G, Perfumo F, Locatelli F, Comoli P. 2007. Prospective monitoring of polyomavirus BK replication and impact of pre-emptive intervention in pediatric kidney recipients. Am J Transplant 7:2727–2735. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funk GA, Gosert R, Comoli P, Ginevri F, Hirsch HH. 2008. Polyomavirus BK replication dynamics in vivo and in silico to predict cytopathology and viral clearance in kidney transplants. Am J Transplant 8:2368–2377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch HH, Vincenti F, Friman S, Tuncer M, Citterio F, Wiecek A, Scheuermann EH, Klinger M, Russ G, Pescovitz MD, Prestele H. 2013. Polyomavirus BK replication in de novo kidney transplant patients receiving tacrolimus or cyclosporine: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Transplant 13:136–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randhawa PS, Finkelstein S, Scantlebury V, Shapiro R, Vivas C, Jordan M, Picken MM, Demetris AJ. 1999. Human polyoma virus-associated interstitial nephritis in the allograft kidney. Transplantation 67:103–109. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binet I, Nickeleit V, Hirsch HH, Prince O, Dalquen P, Gudat F, Mihatsch MJ, Thiel G. 1999. Polyomavirus disease under new immunosuppressive drugs: a cause of renal graft dysfunction and graft loss. Transplantation 67:918–922. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199903270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirsch HH, Randhawa P. 2013. BK polyomavirus in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 13(Suppl 4):S179–S188. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arthur RR, Shah KV, Baust SJ, Santos GW, Saral R. 1986. Association of BK viruria with hemorrhagic cystitis in recipients of bone marrow transplants. N Engl J Med 315:230–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607243150405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cesaro S, Dalianis T, Rinaldo CH, Koskenvuo M, Einsele H, Hirsch HH. 2016. ECIL 6—guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of BK polyomavirus disease in stem cell transplant patients. ECIL 6 Meet, Sophia Antipolis, France, 11–12 September 2015 https://www.ebmt.org/Contents/Resources/Library/ECIL/Documents/2015%20ECIL6/ECIL6-BK-virus-08-12-2015-Cesaro-S-et-al%20final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch HH, Pergam SA. 2016. Human adenovirus, polyomavirus, and parvovirus infections in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, p 1090–1104. In Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Antin H, Appelbaum FR (ed), Thomas' hematopoietic cell transplantation, 5th ed John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom: http://www.wiley.comgoappelbaumTransplantation. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randhawa P, Zygmunt D, Shapiro R, Vats A, Weck K, Swalsky P, Finkelstein S. 2003. Viral regulatory region sequence variations in kidney tissue obtained from patients with BK virus nephropathy. Kidney Int 64:743–747. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bressollette-Bodin C, Coste-Burel M, Hourmant M, Sebille V, Andre-Garnier E, Imbert-Marcille BM. 2005. A prospective longitudinal study of BK virus infection in 104 renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 5:1926–1933. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egli A, Infanti L, Dumoulin A, Buser A, Samaridis J, Stebler C, Gosert R, Hirsch HH. 2009. Prevalence of polyomavirus BK and JC infection and replication in 400 healthy blood donors. J Infect Dis 199:837–846. doi: 10.1086/597126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch HH, Yakhontova K, Lu M, Manzetti J. 2016. BK polyomavirus replication in renal tubular epithelial cells is inhibited by sirolimus, but activated by tacrolimus through a pathway involving FKBP-12. Am J Transplant 16:821–832. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gosert R, Rinaldo CH, Funk GA, Egli A, Ramos E, Drachenberg CB, Hirsch HH. 2008. Polyomavirus BK with rearranged noncoding control region emerge in vivo in renal transplant patients and increase viral replication and cytopathology. J Exp Med 205:841–852. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bethge T, Hachemi HA, Manzetti J, Gosert R, Schaffner W, Hirsch HH. 2015. Sp1 sites in the noncoding control region of BK polyomavirus are key regulators of bidirectional viral early and late gene expression. J Virol 89:3396–3411. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03625-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imperiale MJ, Jiang M. 2015. What DNA viral genomic rearrangements tell us about persistence. J Virol 89:1948–1950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01227-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeCaprio JA, Imperiale MJ, Major EO. 2013. Polyomaviruses, p 1633–1661. Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henriksen S, Tylden GD, Dumoulin A, Sharma BN, Hirsch HH, Rinaldo CH. 2014. The human fetal glial cell line SVG p12 contains infectious BK polyomavirus. J Virol 88:7556–7568. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00696-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernhoff E, Gutteberg TJ, Sandvik K, Hirsch HH, Rinaldo CH. 2008. Cidofovir inhibits polyomavirus BK replication in human renal tubular cells downstream of viral early gene expression. Am J Transplant 8:1413–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markowitz RB, Eaton BA, Kubik MF, Latorra D, McGregor JA, Dynan WS. 1991. BK virus and JC virus shed during pregnancy have predominantly archetypal regulatory regions. J Virol 65:4515–4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Negrini M, Sabbioni S, Arthur RR, Castagnoli A, Barbanti-Brodano G. 1991. Prevalence of the archetypal regulatory region and sequence polymorphisms in nonpassaged BK virus variants. J Virol 65:5092–5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li R, Sharma BN, Linder S, Gutteberg TJ, Hirsch HH, Rinaldo CH. 2013. Characteristics of polyomavirus BK (BKPyV) infection in primary human urothelial cells. Virology 440:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsen GH, Hirsch HH, Rinaldo CH. 2009. Functional analysis of polyomavirus BK non-coding control region quasispecies from kidney transplant recipients. J Med Virol 81:1959–1967. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsen GH, Andresen PA, Hilmarsen HT, Bjorang O, Scott H, Midtvedt K, Rinaldo CH. 2006. Genetic variability in BK virus regulatory regions in urine and kidney biopsies from renal-transplant patients. J Med Virol 78:384–393. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]