Abstract

Introduction

In the United States, Latinos and Blacks are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS, but have been underrepresented in HIV vaccine trials. We assessed screening and enrollment of Blacks and Latinos for preventive HIV vaccine trials conducted in New York City, 2009-2012.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted among 18-50 year old men and transgender women screening for four preventive phase 1 and 2 HIV vaccine trials. Demographic, recruitment, and behavioral/medical eligibility data and outcome of screening were examined. To determine factors associated with enrollment, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed.

Results

Among 6077 individuals who provided contact information, 2536 completed a phone pre-screen. 96 (1.6% of recruitment contacts) enrolled. Latinos were 35.7% of recruitment contacts, but 17.7% of those enrolled, whereas Blacks were 22.5% and 32.3% respectively. Among all Latinos, nearly one third were excluded for being uncircumcised, an eligibility criterion for several studies. In multivariable analysis among potentially eligible potential participants, controlling for age and recruitment method, Latinos were less likely than Whites to enroll in a preventive HIV vaccine trial (aOR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28-0.95) whereas Blacks were as likely as Whites (aOR 0.99, 95% CI 0.59-1.67). Individuals recruited through print advertisements, social media/internet, referral, and other modes were more likely to enroll compared to those recruited through in-person outreach, controlling for age and race/ethnicity.

Conclusions

Targeted outreach has led to substantial inclusion of Latinos and Blacks, with Blacks comprising almost a third of those enrolled in these preventive HIV vaccine trials. Latinos, however, were less likely to enroll compared to Whites. Circumcision status as an eligibility criterion partly accounts for this, but further studies are warranted to address the reasons Latinos decide not to participate in preventive HIV vaccine trials.

Keywords: Preventive HIV Vaccine, Racial/Ethnic Disparities

Introduction

In the United States (US), Blacks and Latinos are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS. In 2013, Blacks comprised 46% and Latinos 21% of new HIV diagnoses, despite comprising 12% and 16% of the US population respectively [1]. New York City (NYC) has one of the largest HIV/AIDS epidemics in the US with an estimated 117,618 people living with HIV/AIDS as of the end of 2013 [2]. In 2013, 42% of new HIV diagnoses were among Blacks and 34% were among Latinos [2]. Historically, however, these groups have been underrepresented in many areas of HIV prevention research. The legacy of the Tuskegee syphilis study, and ongoing racial/ethnic disparities in the US health care system have contributed to this problem [3-5]. Inclusion of these groups in HIV vaccine trials is critical to determine generalizability of trial results and because it is possible that immune responses to preventive HIV vaccines may differ by race/ethnicity [6, 7].

In 1993, US Congress passed a law mandating inclusion of sufficient numbers of women and racial/ethnic minorities into National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored clinical trials [8]. From 1988 to 2002, Blacks accounted for only 10.1% and Latinos 4.2% of participants in National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) sponsored HIV phase 1 and 2 vaccine trials [9]. The HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) and NIAID have launched special initiatives such as the Legacy Project [10], the NIAID HIV Vaccine Research Education Initiative (NHVREI), Be The Generation (BTG) and BTG Bridge [11-13] that aimed to increase participation and engagement of historically underrepresented communities in HIV vaccine prevention research.

A substantial body of literature assesses impediments and willingness to participate in preventive HIV vaccine trials [14-28]. Common barriers include mistrust of government, fear of side effects, stigma, uncertainty of vaccine efficacy, study demands, and vaccine-induced seropositivity (VISP) [14, 21-23, 25, 26]. Some studies indicate that Blacks are more likely to mistrust clinical research and the health care system than other groups [24, 29]. Altruism is the most commonly reported reason for participation, but others include personal benefits such as access to social services, the possibility of vaccine protection, and financial incentives [14, 16, 21, 22, 25, 26].

Several studies reported no difference in willingness to participate by race/ethnicity [15, 21, 24] but others have found variation between groups [16-18, 20]. These findings were predominately derived from studies which assessed willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials or other HIV vaccine related activities without examining actual trial enrollment. To address this, Buchbinder et al showed that hypothetical willingness did not match actual participation by measuring enrollment among those who had reported prior willingness to participate; Blacks, but not Latinos, were more likely to refuse participation months/years later when given the opportunity to enroll in an actual trial [30]. The literature assessing actual participation by racial/ethnic minorities is sparser. One study examining volunteers screening for an HIV vaccine trial in Atlanta, from 2005 to 2007, found white race to be predictive of enrollment [31].

We previously assessed enrollment of Latinos and Blacks into HIV vaccine trials at two research sites in NYC and reported that once engaged in the screening process, they were enrolled at similar proportions [32]. To add to the limited literature on actual participation, we examined the screening and enrollment process for phase 1 and 2 HIV vaccine trials to assess recruitment and enrollment of Latinos and Blacks.

Methods

Study Population

The Columbia University HIV Vaccine Research Site, a NIAID-funded HVTN site, is located in northern Manhattan, a predominantly Latino community [33]. The site conducts both phase 1 and 2 HIV vaccine trials using a variety of recruitment approaches. All recruitment and community education strategies are developed in partnership with the New York Blood Center Project Achieve. The target population consisted of HIV-negative individuals screening for HIV vaccine studies at the site between June 1, 2009 and March 1, 2012.

In this retrospective analysis we included screening data for persons 18-50 years old, who were screening into one of four HVTN trials outlined in Table 1 [34]. Women were excluded because they comprised approximately 7% of persons screening for vaccine trials at the site and were ineligible for the phase 2b study; transgender men, and those with missing data on gender, were also excluded. In addition, those missing data on race/ethnicity or an outcome status, or still undergoing screening at the time of analysis were excluded.

Table 1. HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Trials Included in the Analysis.

| Trial [35] | Phase | Vaccine Regimen | Target Population | Selected Eligibility Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVTN 505 | 2b | Multiclade multigene DNA prime and recombinant adenovirus (rAd) serotype 5 boost | MSM and transgender women at high risk of HIV-1 infectiona | HIV-1 uninfected in good general health by medical history, physical exam, and screening laboratory tests Adenovirus 5 seronegative, circumcised |

| HVTN 205 | 2a | DNA prime and modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) or MVA alone | Men and women at low risk of HIV-1 infectionb | HIV-1 uninfected in good general health by medical history, physical exam, and screening laboratory testsc Vaccinia (small pox) vaccine naïve |

| HVTN 083 | 1 | Prime-boost rAd serotype 35 with HIV-1 clade A Env insert and rAd serotype 5 with HIV-1 clade A or B Env inserts | Men and women at low risk of HIV-1 infectionb | HIV-1 uninfected in good general health by medical history, physical exam, and screening laboratory testsc Adenovirus 5 and 35 seronegative, circumcised |

| HVTN 084 | 1b | A comparison of rAd5 multiclade gag/pol Env to rAd5 gag/pol clade B | Men and women at low risk of HIV-1 infectionb | HIV-1 uninfected in good general health by medical history, physical exam, and screening laboratory testsc Adenovirus 5 seronegative, circumcised |

MSM, men who have sex with men. High risk of HIV infection was defined as reporting unprotected anal intercourse with ≥1 male or transgender female partners, or anal intercourse with ≥2 male or transgender female partners in past six months.

Low risk was defined as ≤2 HIV-negative partners, no new sexually transmitted infections in the past 12 months, and condom use with any non-mutually monogamous partners.

Laboratory evaluations to determine eligibility for Phase 1 and 2a studies were more comprehensive than for phase 2b studies and included, for example, complete blood count, chemistry panel, urinalysis, hepatitis B and C status

Recruitment, Screening, and Enrollment

Individuals were recruited using multiple strategies such as newspaper/magazine advertisements, flyers, referrals from prior/current participants, in-person outreach at events, health fairs, and banner ads on social media websites such as Facebook and Craigslist. For the phase 2b study, participants were recruited by in-person outreach (including Spanish-speaking recruiters, who explained the study, answered questions, and completed contact cards) at bars/clubs, and through national, local, and site-specific advertising campaigns on a study website (www.hopetakesaction.org), Craigslist, Facebook, and sexual networking websites including adam4adam and Manhunt. Individuals responding to web-based or social media ads completed online contact cards. Contact card information (including race/ethnicity) for all recruitment contacts was entered into a database. Follow-up calls were made by staff within 24-72 hours of initial contact; three attempts were made to reach everyone and all interactions were recorded. While individuals reported all methods/sites of recruitment, they were asked to identify one as the primary source of recruitment.

The next step for those who could be reached and agreed was the phone pre-screen questionnaire (PSQ) to determine preliminary eligibility based on self-reported behavioral, medical, and circumcision criteria. This questionnaire was conducted in either English or Spanish depending on the volunteer's preference. Preliminarily eligible individuals were invited to visit the site for HIV vaccine education (HVE) when behavioral and medical eligibility was confirmed, and preventive HIV vaccines, the clinical research process, and the study were explained. Generic screening informed consent was completed at this visit (in preferred language English or Spanish); blood samples were drawn for HIV testing, Adenovirus5 and/or Adenovirus35 antibodies, and general laboratory tests.

If the individual remained interested, a general study visit (GSV) with a physical exam was scheduled. Upon completion of this step, if still eligible and interested, the volunteer was offered the opportunity to sign a protocol-specific consent form (in English or Spanish), and an enrollment visit was scheduled. The entire screening process, from the point of first contact to enrollment, took place over three to five visits in the course of several weeks. Screening could stop at any stage prior to enrollment; reasons were captured via standardized questions and recorded in the database.

Statistical Analysis

Participants were classified as in-screening (still in any phase of the screening process), screening-stopped (regardless of the reason or stage when screening was terminated, includes those who signed screening informed consent but did not enroll), or enrolled in a trial. The primary outcome was enrollment into an HIV vaccine trial and the main independent variable was self-reported race/ethnicity. Race was collected as White, Black/African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, or other. Individuals could choose one or more categories as appropriate, and also recorded whether or not they were of Latino or Hispanic ethnicity. All persons regardless of race who self-identified as Latino or Hispanic were classified as Latino. For analysis, race/ethnicity was categorized as a four level variable: (1) White, (2) Latino, (3) Black, and (4) Other (includes Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, multiracial, and other). The 255 participants with missing race/ethnicity were excluded from the analysis

Univariate analysis to describe the study population was performed. Proportions of different racial/ethnic groups at various stages of the screening process were compared. To determine factors associated with enrollment, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed using the subset that completed the PSQ and were not subsequently excluded for study-specific eligibility criteria (potentially eligible). Two additional logistic regression models were constructed to examine the relationship between reasons for non-enrollment and race/ethnicity; all variables significant at p<0.05 in the bivariable analysis plus variables with epidemiologic importance were included. SAS version 9.3 was used (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC).

Results

During the study period, 6077 men and transgender women were engaged in the screening process for one phase 2b and three phase 1/2a vaccine studies. Nearly half of the study population was between the ages of 25 and 34, and over half were MSM; characteristics by race/ethnicity are shown in Table 2. Numbers of recruitment contacts generated by various recruitment methods differed between racial/ethnic groups. In-person outreach yielded the greatest number of recruitment contacts and its success was similar across all racial/ethnic groups: 88.3% of Whites, 85.5% of Latinos, 83.7% of others, and 71.3% of Blacks. A greater proportion of Blacks were recruited from print advertisements (16.6% vs. 4.9% of Whites and 6.4% of Latinos) and through referrals (5.2% vs. 0.8% of Whites and 1.9% of Latinos) (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of Recruitment Contacts for Phase 1/2a and Phase 2b Preventive HIV Vaccine Trials, New York City, 2009-2012a.

| White n=1950 | Latinob n=2167 | Black n=1370 | Otherc n=590 | Total n=6077 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Gender | |||||

| Men | 1948 (99.9) | 2146 (99.0) | 1357 (99.1) | 588 (99.7) | 6039 (99.4) |

| Transgender Women | 2 (0.1) | 21 (1.0) | 13 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) | 38 (0.6) |

| Total | 1950 | 2167 | 1370 | 590 | 6077 |

| Recruitmentd | |||||

| Outreach | 1713 (88.3) | 1846 (85.5) | 969 (71.3) | 491 (83.7) | 5019 (83.0) |

| Advertisement | 95 (4.9) | 138 (6.4) | 226 (16.6) | 34 (5.8) | 493 (8.2) |

| Web or Social Media | 90 (4.6) | 108 (5.0) | 60 (4.4) | 32 (5.5) | 290 (4.8) |

| Referral | 16 (0.8) | 41 (1.9) | 71 (5.2) | 15 (2.6) | 143 (2.4) |

| Othere | 26 (1.3) | 25 (1.2) | 34 (2.5) | 15 (2.6) | 100 (1.7) |

| Total | 1940 | 2158 | 1360 | 587 | 6045 |

| Age | |||||

| ≤ 24 | 291 (15.2) | 513 (24.1) | 260 (19.3) | 114 (19.6) | 1178 (19.7) |

| 25-34 | 1076 (56.2) | 1009 (47.4) | 559 (41.4) | 307 (52.8) | 2951 (49.4) |

| 35-44 | 394 (20.6) | 472 (22.2) | 325 (24.1) | 122 (21.0) | 1313 (22.0) |

| ≥ 45 | 154 (8.0) | 135 (6.3) | 207 (15.3) | 39 (6.7) | 535 (8.9) |

| Total | 1915 | 2129 | 1351 | 582 | 5977 |

| Sexual Risk Assessedf | |||||

| Low Risk | 200 (30.8) | 263 (37.0) | 217 (37.4) | 76 (36.9) | 766 (35.3) |

| MSM High Risk | 417 (64.3) | 404 (56.9) | 308 (53.0) | 122 (59.2) | 1263 (58.3) |

| Non-MSM High Risk | 32 (4.9) | 43 (6.1) | 56 (9.6) | 8 (3.9) | 139 (6.4) |

| Total | 649 | 710 | 581 | 206 | 2168 |

Numbers may not add up to total because of missing data. Recruitment contacts provided information either through in-person outreach, calling the site in response to print ad, or completing on-line contact card.

Latino represents an ethnicity and thus is not mutually exclusive with other groups, but for purposes of this analysis race/ethnicity was categorized as a four level variable: (1) Latino, and for those who were not Latino, (2) White, (3) Black, and (4) other.

Includes Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, multiracial, other.

Data were captured on all the different methods an individuals reported but were asked to identify one as the main source of recruitment.

Includes blood donation, flyers, other.

Collected during the pre-screen questionnaire, 2536 individuals completed this stage, but sexual risk collected for 2168. High risk defined as reporting unprotected anal intercourse with ≥1 male or transgender female partners, or anal intercourse with ≥2 male or transgender female partners in past six months. Low risk defined as ≤2 HIV-negative partners, no new sexually transmitted infections in the past 12 months, and condom use with any non-mutually monogamous partners.

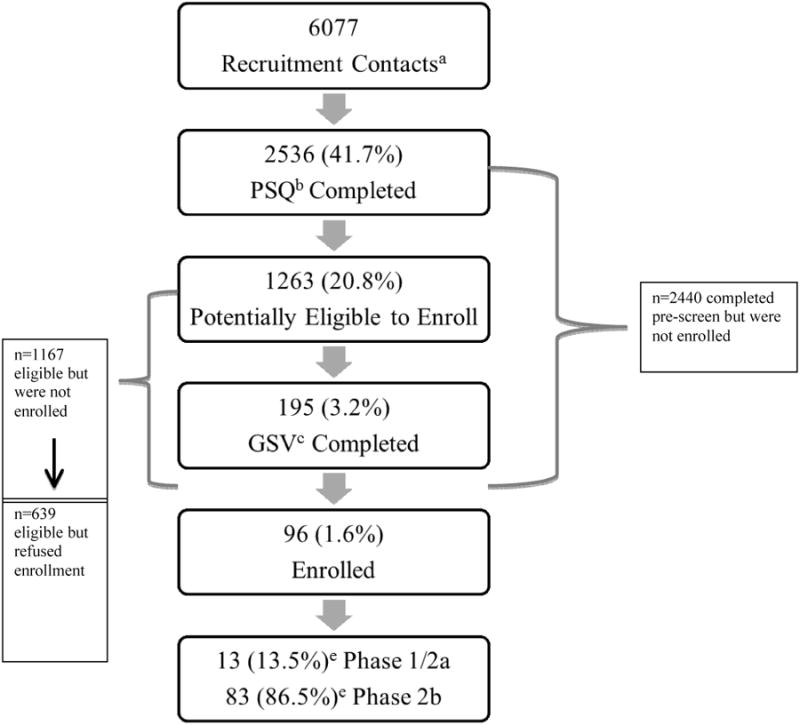

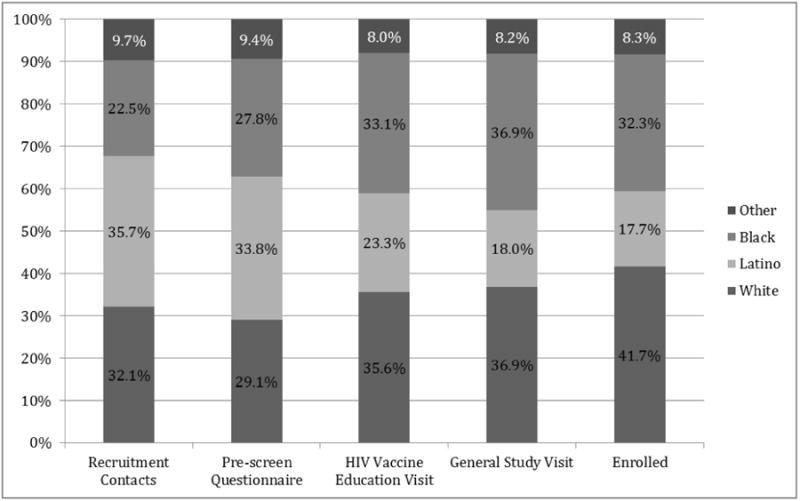

Figure 1 illustrates stages of the screening process from the point of first contact. Out of all recruitment contacts, 2536 (41.7%) completed the phone PSQ, 1263 (20.8%) were potentially eligible to enroll, and 195 (3.2%) completed the GSV. Overall, 96 (1.6% of recruitment contacts) enrolled in a preventive HIV vaccine trial. Of the 96 enrollees, 13.5% enrolled in phase 1/2a and 86.5% phase 2b studies, reflective of the larger size of the phase 2b study (Figure 1). The proportion of racial/ethnic groups varied at different stages of screening and enrollment (Figure 2). Importantly, although Blacks comprised only 22.5% of all recruitment contacts, their representation increased to almost one-third of all enrollees.

Figure 1. Progression through Stages of Screening and Enrollment into Preventive HIV Vaccine Trials.

aRecruitement contacts provided information either through in-person outreach, calling the site in response to print ad, or completing on-line contact card.

bPre-screen questionnaire

cGeneral study visit

ePercentage of enrolled individuals

Figure 2. Representation of Racial/Ethnic Groups Completing each Stage of Screening and Enrollment into HIV Vaccine Trials.

In multivariable analysis of the 1263 potentially eligible individuals who completed PSQ, Latinos were less likely than Whites to enroll in an HIV vaccine trial (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.28-0.95). Moreover, individuals in the 25-34 age group were more likely than those in the 18-24 age group to enroll (aOR 2.08, 95% CI 1.05-4.12). Recruitment methods were strongly associated with enrollment; compared to in-person outreach, those recruited through advertisements or social media/internet were three times as likely to enroll, whereas those recruited through referral or other means, were almost seven times more likely to enroll (Table 3).

Table 3. Variables Associated with Enrollment into HIV Vaccine Trials among those Potentially Eligible, n=1263.

| Variable | Crude Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratioa | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | ref | -- | -- | ref | -- | -- |

| Latino | 0.52 | 0.29, 0.93 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.28, 0.95 | 0.03 |

| Black | 1.19 | 0.72, 1.94 | 0.50 | 0.99 | 0.59, 1.67 | 0.99 |

| Otherb | 0.69 | 0.31, 1.51 | 0.35 | 0.63 | 0.28, 1.40 | 0.26 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18-24 | ref | -- | -- | ref | -- | -- |

| 25-34 | 1.99 | 1.02, 3.89 | 0.04 | 2.08 | 1.05, 4.12 | 0.04 |

| 35-44 | 2.00 | 0.96, 4.21 | 0.06 | 1.60 | 0.74, 3.46 | 0.23 |

| 45-50 | 2.78 | 1.14, 6.80 | 0.03 | 1.96 | 0.78, 4.96 | 0.15 |

| Recruitment Method | ||||||

| Outreach | ref | -- | -- | ref | -- | -- |

| Advertisements | 3.60 | 2.10, 6.18 | <.0001 | 3.57 | 2.04, 6.27 | <.0001 |

| Web or social media | 3.42 | 1.87, 6.27 | <.0001 | 3.69 | 1.99, 6.81 | <.0001 |

| Referral | 6.70 | 2.97, 15.11 | <.0001 | 6.79 | 2.93, 15.72 | <.0001 |

| Otherc | 7.15 | 3.03, 16.89 | <.0001 | 6.96 | 2.89, 16.77 | <.0001 |

The model included only individuals who completed the pre-screen phase and were not excluded for a trial-defined ineligibility, sample size for potentially eligible individuals was 1263, sample size for multivariable analysis was 1254 due to missing data for variables.

Includes Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, multiracial, other.

Includes blood donation, flyers, other.

Circumcision status was a common reason for ineligibility; 29.8% of Latinos and 18.1% overall were excluded for this reason. HIV-infection identified at screening was reason for ineligibility in 4.6% and Adenovirus5 or Adenovirus35 seropositivity in 5.4% of those who stopped screening (Table 4). About one-quarter of individuals who stopped screening actively refused participation, with 44 of these citing concerns about VISP. The proportion of individuals with passive refusal (lost to follow-up) and staff concern about reliability was similar across racial/ethnic groups.

Table 4. Relationship between Reasons for Not Enrolling and Race/Ethnicity among those who Stopped Screening, n=2440a.

| Total | Compared Latino to Whiteb | Compared Black to Whitec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for Not Enrolling | n (%) | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

| Eligibility Criteria | |||||||

| Ad5+ or Ad35+ | 130 (5.4) | 0.55 | 0.32, 0. 93 | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.52, 1.41 | 0.55 |

| HIV-infected | 111 (4.6) | 5.48 | 2.58, 11.66 | <.0001 | 6.34 | 2.96, 13.58 | <.0001 |

| Hepatitis B or C | 27 (1.1) | 0.76 | 0.25, 2.33 | 0.63 | 1.25 | 0.44, 3.53 | 0.68 |

| Uncircumcised | 439 (18.2) | 3.48 | 2.43, 4.99 | <.0001 | 1.40 | 0.92, 2.12 | 0.12 |

| Other clinical | 185 (7.7) | 0.90 | 0.56, 1.43 | 0.65 | 1.20 | 0.76, 1.90 | 0.44 |

| Risk behavior | 345 (14.3) | 1.04 | 0.72, 1.50 | 0.84 | 1.27 | 0.87, 1.84 | 0.21 |

| Participant Refusal | |||||||

| Concern for VISPd | 44 (1.8) | 1.22 | 0.58, 2.56 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.21, 1.39 | 0.20 |

| Other active refusale | 595 (24.7) | 0.56 | 0.42, 0.76 | 0.0002 | 0.53 | 0.38, 0.73 | 0.0001 |

| Other | |||||||

| Staff concern about participation or retention | 33 (1.4) | 2.31 | 0.69, 7.68 | 0.17 | 3.10 | 0.99, 9.74 | 0.53 |

| Lost to follow up | 504 (20.1) | ref | -- | -- | ref | -- | -- |

Adjusted for age and recruitment method. Data were missing on reasons for 27 participants.

Sample size for analysis 1502 and

Sample size for analysis 1338, whites included in both analyses.

Vaccine-induced seropositivity

Other active refusals included concern over vaccine safety or side effects, concern of family member, partner, or friend, logistical reasons such as inconvenient schedule or location, and unspecified refusals.

Assessment of potentially eligible participants who declined enrollment (n=639) showed that 59.2% did not provide a reason for their refusal and another 27.5% cited logistical reasons such as inconvenient schedule or location, moving out of the area, study length or number of study visits. There was a trend that concerns about VISP, vaccine safety, and side-effects in general, including those expressed by a family member, partner, or friend, were more commonly reported by Latinos than other groups: 14.3% of Latinos compared to 11.2% Blacks, 10.5% Whites, and 6.9% other (p=0.38).

Among those excluded for circumcision status compared to those lost to follow-up, the odds of being Latino was three and a half times as high, adjusted for age and recruitment method. Those found to be HIV-infected during screening were more than five and six times more likely to be Latino and Black, respectively, compared to those lost to follow-up. Individuals who actively refused for any reason other than concern about VISP were less likely to be Latino or Black. Those with Adenovirus5 or Adenovirus35 seropositivity were less likely to be Latino compared to White (Table 4).

Discussion

Latinos and Blacks were successfully recruited into a multi-step screening process for HIV vaccine trials up through enrollment. As a result of coordinated HVTN-led efforts and local outreach strategies, 35.7% of individuals who contacted the research site were Latino and 22.5% were Black. These dedicated approaches included development of culturally-appropriate recruitment images and community education campaigns, bilingual research staff, and partnering with diverse stakeholders and local community-based organizations serving Latino and Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer communities. Latinos comprised 17.7% of participants enrolled in HIV vaccine trials. Blacks' representation increased throughout the screening process such that they made up one third of enrollees. Compared to data on participants in NIAID-sponsored phase 1 and 2 HIV vaccine trials from 1988 to 2002 [9], our findings show a fourfold and threefold increase in representation of Latinos and Blacks, respectively. However, compared to our data from 2002 to 2006 [32], we found a similar proportion of Blacks enrolled but fewer Latinos.

The decline in Latinos progressing through screening was in large part due to the circumcision eligibility requirement; almost a third of all Latinos engaged in the screening process were excluded for this reason. In addition, multivariable analysis showed that those excluded for circumcision status were more likely to be Latino even after adjusting for age and recruitment method. However, even in a multivariable model restricted to those who were circumcised and potentially eligible, Latinos were significantly less likely to enroll (aOR 0.52, p=0.03). It is not clear why this is but may be in part be due to concerns about safety, side effects, and VISP which were more commonly expressed by Latinos as a reason to decline participation. This highlights the need to address concerns during community education and outreach activities. In addition, more than half of all participants did not specify why they declined and over a quarter cited reasons related to practical issues; these also require consideration in order to improve enrollment.

Frew et al found that White race was predictive of enrollment, but examined only White compared to non-White [31]. Buchbinder et al showed that Black participants were more likely to refuse enrollment, and although they found no association with Latinos, they did find that safety of the vaccine was of particular concern to both Blacks and Latinos [30]. Focus groups among Latinos revealed common barriers to HIV vaccine trial participation including fear of vaccine-induced infection, side effects, stigma, VISP, and mistrust of government [14, 22]. These findings are consistent with ours; aside from logistical or unspecified refusals, potentially eligible Latinos who actively refused expressed concern about VISP, vaccine safety, and side-effects. In one study, a focus group of Latinos suggested that family was central to decision-making around enrollment into trials [35]. Other studies of focus groups with immigrant Latinos and Blacks found that while these groups identified certain shared barriers to research participation such as fear of experimentation, lack of financial resources, time conflicts, and need for child care, immigrant Latinos had distinct issues including fear of deportation, lack of information about research, and language barriers [36].

While in-person outreach was the major source of contacts screening for HIV vaccine trials, all other methods were positively associated with actual enrollment when compared to in-person outreach. This is likely due to the fact that during outreach, staff initiated the first contact, while with the other methods the volunteer contacted the clinic possibly indicating a higher degree of interest from the beginning. It is not surprising that referral as a recruitment source was associated with enrollment, as an individual would be more likely to enroll if a friend or family member had positive experiences. These findings are in contrast to Frew et al's that recruitment methods did not affect outcomes [31]. We previously reported that web/internet sources of recruitment were more likely to be associated with enrollment [32] than other methods.

Our study has several limitations. For example, no information was available for education or income. Educational attainment has been associated with enrollment in HIV vaccine trials [31]. Income often accounts for some of the observed differences in health outcomes and behaviors by race/ethnicity [37] and may contribute to our results. Further, the lack of information on socioeconomic status may have prevented us from finding differences within racial/ethnic groups; it has been shown that income correlates with HIV conspiracy beliefs [38]. In addition, we had missing data for each of the independent variables, but given the large sample size and low proportion of missing data, this is unlikely to have changed our results substantially. Individuals reported seeing/hearing recruitment messages in more than one location before initiating screening, highlighting that multiple messages and venues are important in successful recruitment. We did not, however, record the number of times a participant encountered recruitment materials/outreach workers before making a decision about screening; this is another potential limitation. Finally, the exclusion of women limits the generalizability of our results.

Despite these limitations, our findings illustrate higher proportions of Latinos and Blacks enrolled in HIV vaccine trials compared to earlier data, but these communities remain underrepresented. In order to reach Latinos and Blacks, substantial and multidimensional efforts are needed, including capitalizing on social media, in-person outreach at venues popular with these communities, Spanish-speaking recruiters and clinic staff, and culturally-appropriate advertisements. Overall, a multiplicity of well-coordinated, culturally-relevant, and sustained approaches and efforts will likely result in greatest success in reaching diverse communities of participants. The role of social media/internet campaigns as an effective tool to reach, engage and educate diverse communities is likely to continue to increase in importance. Based on our data, Latinos were less likely to enroll in these trials compared to Whites. A considerable component of this was due to eligibility criteria, but not all of it. Ongoing education campaigns addressing concerns expressed by this group, as well as further in-depth exploration of barriers and facilitators to Latino participation in HIV vaccine trials is needed. Blacks comprised almost a third of enrollees across four trials at one site, an improved representation of a group historically underrepresented in research. In conclusion, improved recruitment and enrollment of Latinos and Blacks into preventive HIV vaccine trials has been demonstrated, but innovative recruitment efforts and sustained partnerships with these communities are critical and must endure to ensure this trend continues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the recruiters at the research site, the Community Advisory Board and the Community Education and Recruitment Team at the NYC HIV Vaccine Unit, the Community Education and Recruitment Team at the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, the volunteers screening for, and participants of, HIV vaccine trials. We would like to express appreciation to our community partners, Alianza Dominicana, Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD), and Harlem Pride.

MS, JB, RN, SP, SC, VR are supported by grant (U01-AI069470) from NIH/NIAID, and this publication was supported in part by Columbia University's CTSA grant No.UL1TR000040 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 5, 2015];HIV Surveillance Report, 2013. 2015 Feb;25 In; Published. [Google Scholar]

- 2.HIV Epidemiology and Field Services Program. HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2013. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; New York, NY: Dec, 2014. [Accessed March 5, 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans' views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corbie-Smith G. The continuing legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study: considerations for clinical investigation. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:5–8. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montefiori DC, Metch B, McElrath MJ, Self S, Weinhold KJ, Corey L, et al. Demographic factors that influence the neutralizing antibody response in recipients of recombinant HIV-1 gp120 vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1962–1969. doi: 10.1086/425518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocklin SL, Schmitz JE. The role of Fc receptors in HIV infection and vaccine efficacy. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:257–262. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan PS, McNaghten AD, Begley E, Hutchinson A, Cargill VA. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicines. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djomand G, Katzman J, di Tommaso D, Hudgens MG, Counts GW, Koblin BA, et al. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities in NIAID-funded networks of HIV vaccine trials in the United States, 1988 to 2002. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:543–548. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HIV/AIDS Network Coordination. The Legacy Project. https://www.hanc.info/legacy/Pages/default.aspx. In.

- 11.Alio AP, Fields SD, Humes DL, Bunce CA, Wallace SE, Lewis C, et al. Project VOGUE: A partnership for increasing HIV knowledge and HIV vaccine trial awareness among House Ball leaders in Western New York. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2014;26:336–354. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2014.924892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Be the Generation. http://bethegeneration.org/AboutUs/about.html. In.

- 13.HIV/AIDS Network Coordination. Be the Generation Resources. https://www.hanc.info/resources/Pages/BTG-Bridge-Resources.aspx.

- 14.Brooks RA, Newman PA, Duan N, Ortiz DJ. HIV vaccine trial preparedness among Spanish-speaking Latinos in the US. AIDS Care. 2007;19:52–58. doi: 10.1080/09540120600872711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coletti AS, Heagerty P, Sheon AR, Gross M, Koblin BA, Metzger DS, et al. Randomized, controlled evaluation of a prototype informed consent process for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2003;32:161–169. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colfax G, Buchbinder S, Vamshidar G, Celum C, McKirnan D, Neidig J, et al. Motivations for participating in an HIV vaccine efficacy trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2005;39:359–364. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000152039.88422.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhalla S, Poole G, Singer J, Patrick DM, Wood E, Kerr T. Cognitive factors and willingness to participate in an HIV vaccine trial among HIV-negative injection drug users. Vaccine. 2010;28:1663–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frew PM, del Rio C, Clifton S, Archibald M, Hormes JT, Mulligan MJ. Factors influencing HIV vaccine community engagement in the urban South. Journal of Community Health. 2008;33:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frew PM, Mulligan MJ, Hou SI, Chan K, del Rio C. Time will tell: community acceptability of HIV vaccine research before and after the “Step Study” vaccine discontinuation. Open Access J Clin Trials. 2010;2010:149–156. doi: 10.2147/OAJCT.S11915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frew PM, Archibald M, Hixson B, del Rio C. Socioecological influences on community involvement in HIV vaccine research. Vaccine. 2011;29:6136–6143. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koblin BA, Heagerty P, Sheon A, Buchbinder S, Celum C, Douglas JM, et al. Readiness of high-risk populations in the HIV Network for Prevention Trials to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials in the United States. AIDS. 1998;12:785–793. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman PA, Duan N, Roberts KJ, Seiden D, Rudy ET, Swendeman D, et al. HIV vaccine trial participation among ethnic minority communities: barriers, motivators, and implications for recruitment. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2006;41:210–217. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179454.93443.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman PA, Duan N, Lee SJ, Rudy E, Seiden D, Kakinami L, et al. Willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials: the impact of trial attributes. Prev Med. 2007;44:554–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priddy FH, Cheng AC, Salazar LF, Frew PM. Racial and ethnic differences in knowledge and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials in an urban population in the Southeastern US. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2006;17:99–102. doi: 10.1258/095646206775455667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slomka J, Ratliff EA, McCurdy SA, Timpson S, Williams ML. Decisions to participate in research: views of underserved minority drug users with or at risk for HIV. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1224–1232. doi: 10.1080/09540120701866992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voytek CD, Jones KT, Metzger DS. Selectively willing and conditionally able: HIV vaccine trial participation among women at “high risk” of HIV infection. Vaccine. 2011;29:6130–6135. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman PA, Logie C. HIV vaccine acceptability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010;24:1749–1756. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e32833adbe8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhalla S, Poole G. Barriers of enrolment in HIV vaccine trials: a review of HIV vaccine preparedness studies. Vaccine. 2011;29:5850–5859. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen MA, Liang TS, La Salvia T, Tjugum B, Gulakowski RJ, Murguia M. Assessing the attitudes, knowledge, and awareness of HIV vaccine research among adults in the United States. Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;40:617–624. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174655.63653.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchbinder SP, Metch B, Holte SE, Scheer S, Coletti A, Vittinghoff E. Determinants of enrollment in a preventive HIV vaccine trial: hypothetical versus actual willingness and barriers to participation. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2004;36:604–612. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200405010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frew PM, del Rio C, Lu L, Clifton S, Mulligan MJ. Understanding differences in enrollment outcomes among high-risk populations recruited to a phase IIb HIV vaccine trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2009;50:314–319. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181945eec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sobieszczyk ME, Xu G, Goodman K, Lucy D, Koblin BA. Engaging members of African American and Latino communities in preventive HIV vaccine trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2009;51:194–201. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181990605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.New York City demographic shifts, 2000 to 2010. Center for Urban Research, The Graduate Center, City University of New York (CUNY) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 34.HVTN Ongoing Protocols. http://www.hvtn.org/content/dam/hvtn/Science/studies/Ongoing%20Trials%20Compare%20with%20042015_GB.pdf. In.

- 35.Ellington L, Wahab S, Sahami S, Field R, Mooney K. Decision-making issues for randomized clinical trial participation among Hispanics. Cancer Control. 2003;10:84–86. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calderon JL, Baker RS, Fabrega H, Conde JG, Hays RD, Fleming E, et al. An ethno-medical perspective on research participation: a qualitative pilot study. MedGenMed. 2006;8:23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubay LC, Lebrun LA. Health, behavior, and health care disparities: disentangling the effects of income and race in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2012;42:607–625. doi: 10.2190/HS.42.4.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogart LM, Thorburn S. Relationship of African Americans' sociodemographic characteristics to belief in conspiracies about HIV/AIDS and birth control. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1144–1150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]