Abstract

Although medical professionalism is a fundamental aspect of competence in medicine and a distinct facet of physicians’ competence, evidence suggests that the subject of professionalism is not taught or assessed as part of medical students’ curricula in Iran and many other countries. Assessing the knowledge of medical students and physicians about medical professionalism seems to be helpful in identifying the weaknesses of training in the field of professionalism and devise plans for future training on the subject.

The present cross-sectional, quantitative, observational, and prevalence study recruited 149 medical interns, clinical residents, physicians, and professors working in hospitals selected through stratified random sampling using a questionnaire designed by the researchers and confirmed for its validity and reliability. The results were analyzed by Stata at a significance level of 0.05.

Out of 149 cases, 61.64% were male with the mean age of 30.81 years. A total of 66 participants (44.29%) (95% confidence interval [CI]: 36.44%–52.44%) had heard and 83 (55.70%) (95% CI: 47.55%–63.55%) had not heard the term “medical professionalism” before the study. After adjusting for potential confounders, age and degree did not have statistically significant difference in assessed knowledge of medical professionalism, but sex had (mean difference: 5.88, P = 0.045), and the mean of the female was significantly higher than that of the male participants. The mean percentage of correct answers was 47.67.

The present study demonstrated that the medical professionals working in the national healthcare system have an unfavorable theoretical knowledge about medical professionalism in Iran; although this does not indicate that their practices are unethical, it should be noted that one of the prerequisites of possessing a high level of medical professionalism and for establishing a proper relationship between the medical community and the patients is to have a proper knowledge of this concept. Improving behaviors and performances in medical professions requires adequate training on the concepts of medical professionalism and consequently the assessment of the levels of professionalism achieved in medical professionals.

Keywords: medical professionalism, medical ethics, medical education

1. Introduction

Medical professionalism is not a new concept and has always been present throughout the history of medicine in the form of a Hippocratic Oath taken by physicians. The key to an effective doctor–patient relationship and a successful diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of diseases is the patient's trust on the physician. The public trust in medical professionals makes medicine a sacred and valuable profession. This trust is that the main goal of medical professionals is to ensure public health and that this goal is prioritized by them over all their own interests. Medical professionals undertake this sacred goal through an oath.[1] Medical professionalism is a fundamental aspect of competence in medicine. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in the United States has emphasized 6 core competencies in all residency “training and assessment” programs. Professionalism constitutes 1 of the 6 competencies. Professional competence is the constant and conscious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, and values and is reflected in daily practices through serving the interests of individuals and the society.[2,3] Major medical organizations have provided several definitions for medical professionalism. International North American and European experts have helped define professionalism. In one of its publications, the General Medical Council describes the duties of a physician with good medical practice as providing good clinical care, maintaining good medical practice, learning and teaching, communication with patients, interaction with colleagues, probity, and health.[4]

Professionalism is an ancient and respectable concept in medicine exemplified by the Hippocratic Oath or its versions taken by medical students in their graduation ceremonies. In the modern age, professionalism holds the same significance and relevance for the world that it held 2500 years ago for Hippocrates. The ACGME defines professionalism as “a commitment to perform professional responsibilities, adhere to ethical principles and be sensitive to the diversity of patients’ population”. This broad and universal definition of professionalism has both advantages and disadvantages.[5–7]

In recent years, professionalism has been a widely emphasized subject in medical education and medical practices. Although it is a good change, there is still a lack of common understanding about the meaning of the concept. Discussions on the subject have thus been unsystematic, as the term professionalism has multiple meanings, complexities, and subtle differences.[8] Despite this lack of common understanding, medical professionalism is largely taken to consist of a set of behaviors, including

Physicians’ preferring others’ interests over their own.

Physicians’ adhering to high ethical standards.

Physicians’ responding to social needs and their behaviors reflecting a social contract to serve the community.

Physicians’ representing basic human values, including trustworthiness and honesty, compassion and sympathy, altruism and empathy, and respect for others and trust.

Physicians’ being accountable for their own and their colleagues’ actions.

Physicians’ being committed to excellence.

Physicians’ being committed to conducting research and updating their knowledge and using them in their professional field.

Physicians’ dealing with high levels of complexity and uncertainty.

Clinical competence, communication skills, and a correct understanding of the ethical and legal aspects of medicine constitute the framework of medical professionalism and include features such as accountability, altruism, excellence, and humanism. The capstone of this framework is the realization of medical professionalism or the making of a perfect physician. The reasons for providing medical professionalism training and assessment to medical students and practicing physicians include the patients’ expectations; the relationship between professionalism and improved clinical outcomes (i.e., the relationship between unprofessionalism and its consequences); the accreditation of organizational needs; and the observation that professionalism can be taught, learned, and assessed. Methods of teaching professionalism including lectures, group discussion, simulations and rolemodeling should be assessed to ensure that medical students and practicing physicians are competant in medical professionalism. Approaches to the assessment of professionalism include the use of various tools and the presence of observers. The assessment of professionalism can be used for formative and summative feedback, the assessment of programs on professionalism, and the development of a hypothesis for research on professionalism.[10,11]

Several methods exist for the assessment of medical professionalism. Arnold[12] classified the assessment tools used for medical professionalism in 3 categories that consider professionalism as part of clinical competence and then argued that the development of good qualitative methods is necessary for strengthening quantitative methods and that further research is required into the environment in which assessments should be carried out. Methods of assessing medical professionalism include peer assessment, direct observation, patient assessment, Objective Structured Clinical Examination, Standardized Patient Assessment, student evaluation forms, self-assessment, educational portfolios, teamwork, Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise, supervisors’ reports, videotape analysis, and Single Best Answer Multiple Choice Situational Judgment Tests.[6,13]

This competence is required to be incorporated into general medicine training and residency education in all fields of medicine so that all medical students are competent in medical professionalism. In addition to teaching the knowledge and skills required for acquiring this competence, medical students and practicing physicians should be assessed on their professionalism in order to determine the attitude and performance of different medical professions with regard to this subject; the results obtained through these short- and long-term evaluations can then be used for the development and promotion of this essential competence. Although apparently an important subject to Iranian medical professionals, only a limited number of noncomprehensive studies have been conducted on medical professionalism in Iran.[14] Evidence suggests that the subject of professionalism is not taught or assessed as part of medical students’ curricula, especially in the case of general medicine and residency programs. Assessing the knowledge of medical professionalism in medical students and physicians helps identify the weaknesses of professionalism training and devise plans for future training on the subject.[15] The present study was conducted to explore the knowledge of students in both general medicine and residency programs as well as physicians practicing in teaching hospitals affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences about the subject of professionalism. The results of this study can help the medical community in its efforts to develop competence in professionalism.

2. Methods

This cross-sectional, quantitative, observational, and prevalence study was conducted in 2014 to 2015 in Tehran, Iran. In this study, the authors developed a questionnaire in 2 parts; the first part examines participants’ familiarity with the term and the definitions of the term (professionalism), and the second part examines their knowledge in areas related to professionalism based on the resources available (books; guidelines; research papers by using search engines like MEDLINE, ERIC, HAPI, PsychINFO; and search terms such as professionalism, duty, ethics in combination with evaluation, assessment, and measurement). After the collaborators of the project revised the questionnaire and prepared its final version, 15 professors and colleagues with an expertise in the field assessed its validity. A total of 11 validity assessment forms were returned to the researchers for the first and second versions of the questionnaire. The researchers modified the questionnaires according to the comments the reviewers had made on the items for ensuring their clarification. The validity of the questionnaire was then analyzed and confirmed. The mean score of validity for the questionnaire (including its relevance, clarity, and simplicity) was 0.899. The final version of the questionnaire was distributed among 25 study participants for measuring its reliability. Internal consistency (reliability) of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach alpha, which was obtained as 0.755 for the 21 items of the questionnaire.

The study was conducted in 2 stages after the distribution of the questionnaire. First, the first part of the questionnaire was distributed among the participants. After collecting the completed first part, the second part of the questionnaire was distributed among the same group with a unique code. The first part of the questionnaire examined familiarity with the term and the definitions of the term, and the second part of the questionnaire examined areas related to professionalism. In this study, the main outcome was evaluating knowledge of professionalism in medical interns, clinical residents, physicians, and professors.

The study population consisted of 150 medical interns, clinical residents, physicians, and professors working in hospitals affiliated with the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The sample size required for the study was calculated using the following equation:

|

where Z is the standard normal score with 95% confidence interval (CI) (α = 0.05), S is the standard deviation of the variable, and d is maximum acceptable error. The variance was estimated at 0.06709 in the pilot study. The sample size required for the study was estimated at 103 with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 0.05. To take account of potential errors and sample loss, which is common in cross-sectional studies, 150 questionnaires were completed. Participants were selected from some hospitals in Tehran (capital city of Iran) by stratified random sampling method. Stratified sampling is a random sampling technique wherein the investigator divides the whole population into different strata or groups, then randomly selects the final subjects proportionally from the strata. In this study, the population was divided into 3 strata including medical interns (students), General Practitioner (GP)s and residents, and specialists. Then the needed sample size was randomly selected from each stratum proportionate to the population size of the stratum when viewed against the entire population.

Baseline characteristics of the subjects were presented as mean Standard Deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables with 95% CI. The data were analyzed by independent samples Student t test, Analysis Of Variance (ANOVA), and linear regression model. In all analyses, a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Stata software version 13 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) was used for data analyses.

Ethical points such as participants’ personal information confidentiality are considered. The questionnaires are anonymous and identified by codes. A verbal consent was obtained from participants before distributing the questionnaires. Ethical considerations will also be taken into account in the dissemination of the data and the publication of the results.

3. Results

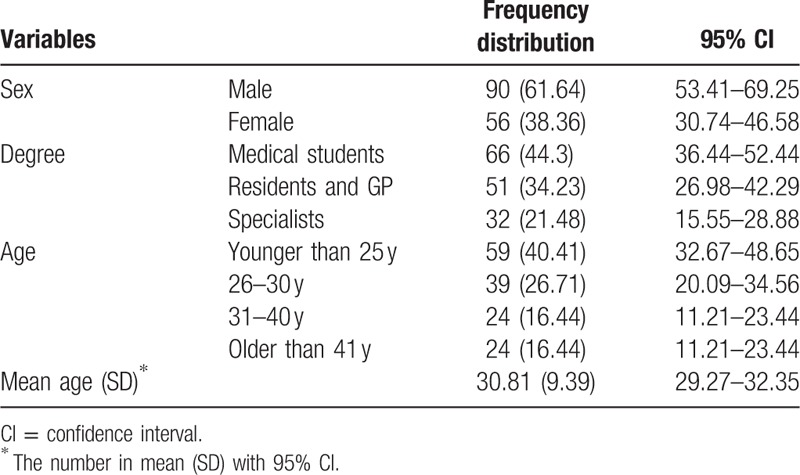

A total of 149 questionnaires were completed for the study, and their analysis then yielded a set of data. One of the questionnaires was returned blank on the second part and was excluded from the analysis. As shown in Table 1, 3 out of 149 participants did not disclose their gender and of the remaining 146, 90 were male (61.64%) and 56 were female (38.36%). A total of 146 participants disclosed their age, whose mean age was 30.81 years (95% CI: 29.27–32.35, with range 23–64 years) with the standard deviation of 9.39. Regarding age distribution, 40.41% were younger than 25 years, 26.71% were 26 to 30 years old, 16.44% were 31 to 40 years old, and 21.48% were older than 41 years. Of the participants, 44.30% were medical students; 34.23% were medical residents and general practitioners; and 21.48% were fellows, specialists, or had higher degrees of education. Of the whole study population, 66 (44.29%) (95% CI: 36.44%–52.44%) had heard and 83 (55.70%) (95% CI: 47.55%–63.55%) had not heard the term “medical professionalism” before.

Table 1.

The frequency distribution of demographic characteristics of participants.

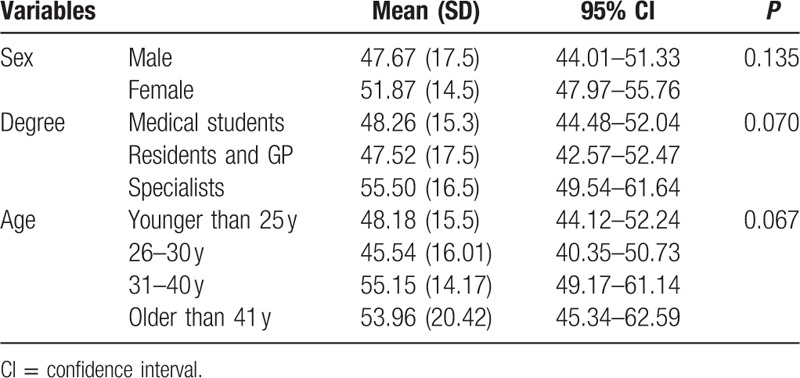

As shown in Table 2, mean of the percentage of correct answers in male and female was 47.67 (SD: 17.5) and 51.87 (SD: 14.54), respectively, and t test revealed no significant difference between mean of percentage of correct answers in male and female (P = 0.135). The mean percentage of correct answers in students, GP and residents, and specialist was 48.26, 47.52, and 55.50, respectively. Based on ANOVA test, there was no significant difference between the mean percentage of correct answers by degree levels (P = 0.070). Age was analyzed in continuous and categorized scale in the relation with knowledge of professionalism, and there was no significant relationship in both scale of age and knowledge of professionalism (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

The relationship of independent variables with participants’ knowledge of professionalism.

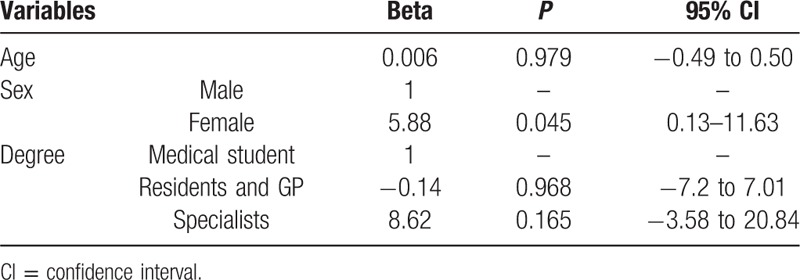

After adjusting for potential confounders in the linear regression model, age and degree did not have a significant difference but the mean difference of male and female (mean difference: 5.88) after adjusting for age and degree was statistically significant (P = 0.045), and the mean of the female was significantly higher than that of the male participants (Table 3).

Table 3.

The adjusted analysis of variables by linear regression model on participants’ knowledge of professionalism.

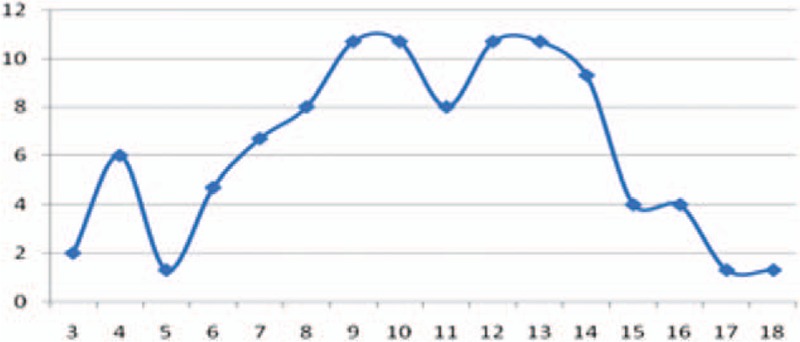

Table 4 presents the results obtained on participants’ knowledge of professionalism separately for each question and in percentage. A total of 149 participants out of the 150 responded to these questions. As shown in Fig. 1, 3 participants (2.0%) responded correctly to only 3 of the items on the knowledge of professionalism (14.29% of the items) and 2 participants (1.3%) responded correctly to 18 of the 21 items (85.71% of the items), and the maximum number of correct answers were given to 9, 10, 12, and 13 items (each of which received 16 correct responses or 10.7%).

Table 4.

Participants’ responses to the questions about professionalism for each question in percentage.

Figure 1.

The relative frequency of participants’ correct responses to the items on the knowledge of professionalism.

4. Discussions and conclusion

Professionalism is a set of values and behaviors that reinforce the social contraction between patient and physicians. Weak professionalism in physicians is a fundamental cause of medical malpractice and mortality and morbidity in patients.[16] A study showed that cultural similarities and differences have a strong impact on the concept of professionalism in a manner that a universally acceptable concept about medical professionalism is difficult.[17] However, medical students learn these values during their education, many studies show that certain aspects of professionalism seem to be underdeveloped in medical students and need to be targeted for teaching and assessment in order to develop professionally responsible practitioners.[16] One of these studies that assessed knowledge in professionalism in 2 to 4, sixth-year medical students showed that medical curricula are not sufficiently sophisticated for reaching this aim.[18]

Another study in 937 students in China revealed that medical curricula for undergraduate students are neither sophisticated nor comprehensive in teaching medical professionalism.[19] A similar study in assessing knowledge and attitudes toward medical professionalism among students and junior doctors showed that there is limited knowledge but good attitude toward medical professionalism and formal training, and educational programs must be revised in this regard.[20]

Byszewski et al[21] suggested that the main values in patient care are compassion, empathy, altruism, and integrity (honesty), which are taken to define medical professionalism. In their study, they investigated medical students’ perception of professionalism after having added it to their curricula.[21] Although a large number of tools have been described for assessing professionalism, the majority of studies show the lack of a single tool specifically used for measuring all the aspects of medical professionalism. Many authors have noted the importance of a multifaceted approach through a range of tools used in school curricula for assessing formative and summative objectives.[2,11]

The present study, therefore, examined the level of knowledge in physicians and medical students. For this purpose, the researchers interviewed 150 medical students, general practitioners, medical residents, and specialists working at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their knowledge on professionalism. The results of this study can be used for determining the effectiveness of the changes made in the knowledge of medical professionals and students and for developing a proper curriculum. Blue et al[22] and Jiang et al[19] have also noted this application in their papers. A study in Canada also showed that medical curriculum for family physicians is not sophisticated for learning medical ethics and professionalism.[23] The results of the present study indicated that, despite the significance of the issue, only 44.7% of participants had heard the term “medical professionalism”. The researchers could not find any studies on the subject with relevant results.

An average of 49.57% of participants responded correctly to the items on the knowledge of professionalism. The mean rate of correct answers was 51.87% in women and 47.67% in men. After adjusting for age and degree, a statistically significant difference was observed between the genders in their mean level of knowledge, and females had a significantly higher mean than males (P value 0.045). The review of the literature yielded no relevant studies that could be compared to the present one. The leading countries in the discussion of medical professionalism appear to have focused more on the adherence to professional standards in medical and healthcare professionals and to have assessed their knowledge of medical professionalism through educational programs. The researchers were unable to find relevant studies assessing medical professionals’ knowledge on the subject under examination.

In terms of the level of education, the mean rate of correct answers was 48.26% in the medical students, 47.52% in the medical residents and general practitioners, and 55.50% in the specialists and those with higher degrees of education; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05). The results show that it is necessary to arrange teaching programs in the field of professionalism for both general practitioners and medical residents.

Despite the importance of the issue, the medical professionals working in the national healthcare system appear to have an unfavorable theoretical knowledge about medical professionalism; although this unfavorable status does not indicate that their practices are unethical, it should be noted that one of the prerequisites for possessing a high level of medical professionalism and for establishing a proper relationship between the medical community and the patients is to have a proper knowledge of this essential concept. Improving behaviors and performances in medical professions requires adequate training on the concepts of medical professionalism and consequently the assessment of the levels of professionalism achieved in medical professionals.

5. Limitations

The study evaluated just the knowledge of physicians and medical students on medical professionalism and other aspects of medicine, including the attitudes and behavior, were not studied. Although the validity of the questionnaire is checked by researchers, there is no certainty about whether this questionnaire really reflects the true awareness of professionalism among responders. The study was conducted in teaching hospitals, and the results cannot be generalized to all hospitals and medical community. It must be considered that medical professionalism is under the category of medical ethics and can be different in different countries according to their culture and values.

6. Recommendations

According to the results obtained from this study, a course on medical professionalism is recommended to be added to the curriculum of students in all fields of medicine covering any relevant concept and to then be followed by a pregraduation assessment of the professional performance of the students. The Medical Council and related organizations are also recommended to pursue education on medical professionalism for medical professionals more actively. More comprehensive studies are also recommended to be proposed, approved, and carried out in areas related to medical professionalism, with adequate sample sizes and with the support of medical universities and the Medical Council for achieving more comprehensive results. This subject is worth becoming a research priority for medical universities.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the School of Traditional Medicine at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for funding the study; the faculty's Deputy of Education and Research for supporting the project; and all the professors, physicians, and students who participated in the study and completed the questionnaires.

There is no funding source for this study and shahid beheshti university of medical sciences and school of traditional medicine supported in performing the study such as gathering data and approving in ethics in research committee.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: ACGME = Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lynch DC, Surdyk PM, Eiser AR. Assessing professionalism: a review of the literature. Med Teach 2004; 26:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynne M, Kirk MD. Professionalism in medicine: definitions and considerations for teaching. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2007; 20:13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002; 287:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Passi V, Doug M, Peile E, et al. Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ 2010; 1:19–29.ISSN: 2042-6372. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andrew G. Lee, Hilary A. Beaver, H. Culver Boldt, Richard Olson, Thomas A. Oetting, Michael Abramoff, and Keith Carter, Teaching and Assessing Professionalism in Ophthalmology Residency Training Programs 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACGME Outcome project. Available from www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compFull.asp. 2007 [Accessed on February 13, 2006] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Project of the ABIM Foundation; ACP–ASIM Foundation; European Federation of Internal Medicine Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:243–246.(American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136(3):243–246.). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swick Herbert M. MD, Toward a Normative Definition of Medical Professionalism. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sethuraman KR. Professionalism in medicine. Reg Health Forum 2006; 10:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller PS. Incorporating professionalism into medical education: the Mayo Clinic experience. Keio J Med 2009; 58:133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of americal medial collages, Cohen JJ. “The work ahead”: AAMC's president address. 2005; Available at http://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/july06/word.htm. [Accessed August 28, 2006]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold L. Assessing professional behavior: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med 2002; 77:502–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, et al. Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev 2002; 59:293–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bazmi S, Kiani M, Hashemi Nazari SS, et al. Assessment of patients’ awareness of their rights in teaching hospitals in Iran. Med Sci Law 2016; 56:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ForatiKashani M, Dabiran S, Noroozi M, et al. Evaluation of professional commitment in Tehran University of Medical Sciences residents from patients view point. J Ethics Hist Med 2010; 4:46–56.(In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Sullivan AJ, Toohey SM. Assessment of professionalism in undergraduate medical students. Med Teach 2008; 30:280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandratilake M, McAleer S, Gibson J. Cultural similarities and differences in medical professionalism: a multi-region study. Med Educ 2012; 46:257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woloschuk W, Harasym PH, Temple W. Attitude change during medical school: a cohort study. Med Educ 2004; 38:522–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang S, Yan Z, Xie X, et al. Initial knowledge of medical professionalism among Chinese medical students. Med Teach 2010; 32:961–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters D, Ramsewak SS, Youssef FF. Knowledge of and attitudes toward medical professionalism among students and junior doctors in Trinidad and Tobago. West Indian Med J 2015; 64:138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byszewski A, Hendelman W, McGuinty C, et al. Wanted: role models—medical students’ perceptions of professionalism. BMC Med Educ 2012; 12:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blue AV, Crandall S, Nowacek G, et al. Assessment of matriculating medical students’ knowledge and attitudes towards professionalism. Med Teach 2009; 31:928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merril A. Pauls, Teaching and evaluation of ethics and professionalism in Canadian family medicine residency programs. Can Fam Phys 2012; 58:752–756. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]