Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the toxicity and activity against HIV of 5-hydroxytyrosol as a potential microbicide.

Design:

The anti-HIV-1 activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol, a polyphenolic compound, was tested against wild-type HIV-1 and viral clones resistant to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors and integrase inhibitors. In addition to its activity against founder viruses, different viral subtypes and potential synergy with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine and emtricitabine was also tested. 5-Hydroxytyrosol toxicity was evaluated in vivo in rabbit vaginal mucosa.

Methods:

We have cloned pol gene from drug-resistant HIV-1 isolated from infected patients and env gene from Fiebeg III/IV patients or A, C, D, E, F and G subtypes in the NL4.3-Ren backbone. 5-Hydroxytyrosol anti-HIV-1 activity was evaluated in infections of MT-2, U87-CCR5 or peripheral blood mononuclear cells preactivated with phytohemagglutinin + interleukin-2 with viruses obtained through 293T transfections. Inhibitory concentration 50% and cytotoxic concentration 50% were calculated. Synergy was analysed according to Chou and Talalay method. In-vivo toxicity was evaluated for 14 days in rabbit vaginal mucosa.

Results:

5-Hydroxytyrosol inhibited HIV-1 infections of recombinant or wild-type viruses in all the target cells tested. Moreover, 5-hydroxytyrosol showed similar inhibitory concentration 50% values for infections with NRTIs, NNRTIs, protease inhibitors and INIs resistant viruses; founder viruses and all the subtypes tested. Combination of 5-hydroxytyrosol with tenofovir was found to be synergistic, whereas it was additive with lamivudine and emtricitabine. In-vivo toxicity of 5-hydroxytyrosol was very low even at the highest tested doses.

Conclusion:

5-Hydroxytyrosol displayed a broad anti-HIV-1 activity in different cells systems in the absent of in-vivo toxicity, therefore supporting its candidacy as a potential new class of microbicides.

Keywords: antiretrovirals, HIV, HIV prevention, microbicides

Objective and design

HIV spreads through parenteral, vertical or sexual transmission, and treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART) must be maintained for life. Only 17 million of the almost 37 million people infected with HIV are currently on ART [1]. Although a vaccine would be the ultimate tool in HIV prevention, the achievement of partial protection in vaccine trials have led scientific community to search for other preventive methods including topical microbicides or preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Concerning microbicides, the CAPRISA004 study was based on a gel containing tenofovir (TFV) topically applied before and after the sexual intercourse showing a reduced the risk of HIV infection through heterosexual intercourse by almost 40% [2]. Similarly, the iPrEx study showed that a combination of emtricitabine (FTC) and TFV was 44% effective in preventing infection in MSM [3]. These studies were the first ones in which a drug prevention method was able to diminish chances of infection. In regard to PrEP, the HPTN 052 trial showed that ART given to HIV seropositive heterosexual individuals with healthy immune systems reduced by 96% the risk of infection for their uninfected partners [4]. However, recently, oral and topical drug prophylactic treatment of African women in the VOICE study showed no benefits at all, likely because adherence was very low [5]. On the other hand, two different studies showed that the combination of TFV and FTC used as prophylaxis was highly effective in reducing the rate of HIV infection [6], whereas a recent study confirmed that no new HIV infections were observed with PrEP in a clinical setting [7]. Therefore, although the use of ART as prophylactic strategy seems to be effective, it raises some concerns of long-term toxicity and potential emergence of viral resistance. In this regard, nontoxic drug development would be useful to avoid both viral resistance and drug toxicity. Moreover, HIV strains resistant to currently used ART are circulating worldwide, and thus they will be unlikely affected by PrEP strategies in a global scenario.

Topical or oral prophylactic treatment should be especially used in developing countries, which cannot afford ART economic costs and are strongly hit by AIDS epidemic and would be the only method controlled by women. Therefore, new developed microbicides should be both efficacious and cheap. Among other candidates, 5-hydroxytyrosol is a polyphenol derivative displaying known antioxidant properties. In addition, previous independent research showed that 5-hydroxytyrosol exerted an anti-HIV activity in vitro mainly targeting the viral integrase and the envelope-mediated fusion with host target cells [8–10]. Although 5-hydroxytyrosol is not suitable for development as an orally available antiretroviral agent due to its low intrinsic activity, in the μmol/l range, its chemical properties, easy formulation, barrier diffusion and lack of toxicity support the hypothesis that it could be an excellent microbicide candidate.

In the present study, we show that 5-hydroxytyrosol inhibited the replication of several HIV-1 strains, including drug-resistant isolates as well as founder viruses in either additive or synergistic fashion in the presence of other antiviral agents and without toxic effects in vivo, therefore supporting its development as a potential new microbicide candidate.

Methods

Reagents

5-Hydroxytyrosol was provided by Seprox Biotech (Madrid, Spain). 5-Hydroxytyrosol was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Quentin Fallavier, France), at 100 mmol/l, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), NIH, (Germantown, Maryland, USA): TFV, lamivudine (3TC), emtricitabine (FTC), nevirapine and raltegravir (RTG).

Primary cells and cell lines

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy blood donors by centrifugation through a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (Pharmacia Corporation, North Peapack, New Jersey, USA).

MT-2 cells and PBMCs were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute - 1640 (RPMI-1640) medium and 293T and U87.CD4CCR5 cells in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) medium, both containing 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/l l-glutamine, penicillin (50 IU/ml) and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) (all Whittaker M.A. Bio-Products, Walkerville, Maryland, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and split twice a week. PBMCs were preactivated with PHA (5 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) and interleukin-2 (300 IU/ml) before use. U87 cell line, stably expressing CD4+ and CCR5 (U87.CD4+.CCR5), was maintained in DMEM containing G418 (300 mg/l) (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) and puromycin (1 mg/l) (Sigma-Aldrich).

Plasmids and virus

Wild-type X4-tropic NL4.3 and R5-tropic HIV-1Bal were expanded through several passages in MT-2 cells or human PBMCs. Plasmids pNL4.3-Luc [11], pNL4.3 [12] and pJR Renilla [13] have been previously described.

Resistant viruses

Q148K (integrase), K65R and M184V (retrotranscriptase) mutations were introduced by Polymerase chain reaction in pNL4.3-Ren clone using the QuickChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA) to produce replication-competent viruses expressing the Renilla reporter gene. Multiresistant viruses were generated by cloning the full-length HIV-1 pol gene amplified from patient's serum in the pNL4.3-lacZ/pol-Ren vector as described previously [12,14].

HIV subtypes

Subtypes of recombinant HIV-1 were generated by cloning the full-length HIV-1 envelope (Env) in pNL-lacZ/env-Ren vector as described previously [13]. The Env of VI-191 (subtype A), 92BR025 (subtype C), 92UG024 (subtype D) and CM244 (subtype E) strains were amplified from culture supernatants kindly provided by Holmes et al.[15] (NIBSC, London, UK) through the NeutNet consortium. The Env from strains X-845-4 (subtype F1) and X-1628-2 (subtype G) obtained from culture supernatants were kindly provided by Lucía Pérez Álvarez (ISCIII, Madrid, Spain).

Primoinfection viruses

Transmitted/founder viruses from acutely infected patients were identified at the Centro Sanitario Sandoval. Plasma samples from three HIV-1-infected patients were tested for p24 antigen and virus-specific antibodies (Ab) and then classified according to Fiebig et al.[16]. These patients had HIV-1 Ab detectable by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), but either negative (Fiebig stage III) or indeterminate (Fiebig stage IV) by western blot, indicating recent infection. Plasma samples from Transmitted-Founder viruses were recovered, and full-length env genes were amplified from plasma RNA of three HIV-1-infected patients. Recombinant viruses were generated by cloning their full-length Envs in the pNL-lacZ/Env-Ren vector as described previously [13].

Anti-HIV activity evaluation

Infectious supernatants were obtained from calcium phosphate transfection on 293T cells and used to infect cells in the presence or absence of different concentrations of 5-hydroxytyrosol. The quantification of anti-HIV activity was performed 48 h postinfection by two different parameters depending on the virus used. First, for Renilla-luciferase viruses, cell cultures were lysed with 100 μl of buffer and relative luminescence units were obtained in a luminometre (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany) after the addition of substrate to cell extracts following the specifications of ‘Renilla-luciferase assay system’ (both Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Second, by measuring p24-Gag antigen amount in supernatants using a commercially available ELISA kit (Innotest-HIV-antigen mAb; Innogenetics, Zwijndrecht, Belgium) [17] for viruses not expressing Renilla-luciferase. Cell viability in treated mock-infected cells was measured in parallel with same conditions as in the antiviral assay by CellTiter Glo (Promega) assay system. Inhibitory concentrations 50% and cytotoxic concentrations 50% (CC50) were calculated using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, California, USA).

Combination experiments

5-Hydroxytyrosol was tested in combination with TFV, 3TC and FTC. Inhibitory concentration 50%/inhibitory concentration 50% ratios were determined in different drug combinations, and anti-HIV evaluation of each compound was determined separately and in combination upon infection with an X4-tropic recombinant virus (NL4.3-Ren). The Calcusyn Software (Cambridge, UK) was used to evaluate combination index for each combination.

RAJI-DC-SIGN transfer assay

RAJI-DC-SIGN cells were preincubated with 5-hydroxytyrosol (final concentrations: 100, 10 and 1 μmol/l). An hour later, viral supernatants (NL4.3-Renilla) were added. Two hours later, cells were resuspended in RPMI with 5-hydroxytyrosol at the same concentrations. Afterwards, cultures were cocultured with preactivated PBMCs/well to assess inhibition of virus transfer by RAJI-DC-SIGN cells [18]. Cell culture was lysed 48 h after infection, and virus replication was measured as described above.

In-vivo toxicity

5-Hydroxytyrosol gel was administered for 14 consecutive days by topical route to the vaginal mucosa of rabbits. The animals received 1 ml/animal per day of three different doses (30, 100 and 200 mmol/l). All animals were sacrificed at the end of the treatment period. Mortality/viability, clinical signs and body weight were recorded during the study. The day before treatment start, a vaginal smear sample was taken from the vaginal mucosa for microbiological assessment. Vaginal pH was measured immediately after sacrifice of the animals. A macroscopic examination of the genital apparatus of each animal was performed with special emphasis on the vaginal surface. Microbiological assessments were performed on samples of vaginal mucosa. Sections of the distal, medial and proximal zones of the vagina were collected for microscopic examination (epithelium, leukocyte infiltration, vascular congestion and oedema), and cell culture of the vaginal exudates was performed to identify bacteria in the flora of the vagina.

Results

Anti-HIV activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol in vitro

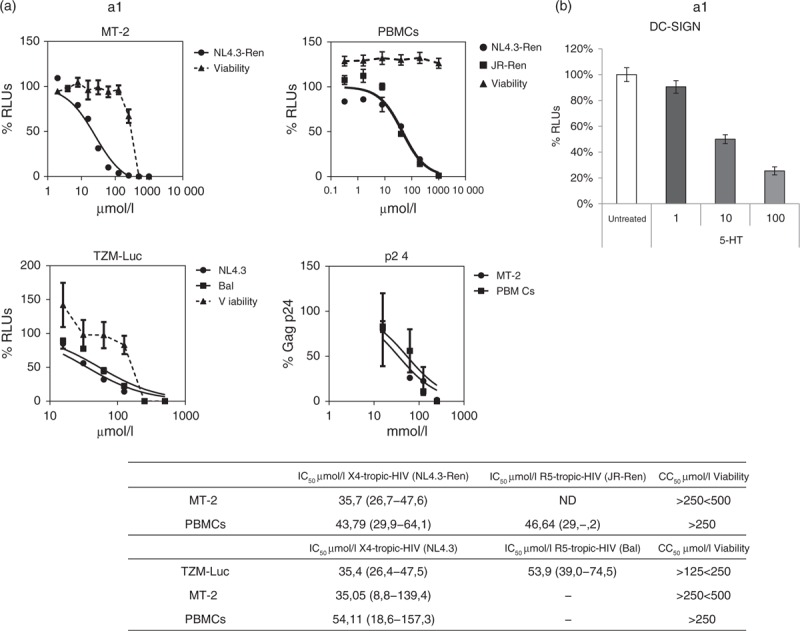

5-Hydroxytyrosol infection inhibition by R5-tropic or X4-tropic HIV-1 was evaluated in different target cells using either the recombinant virus assay [12] or a classic p24 Gag detection assay. Both assays were performed in lymphoblastic cell lines (MT-2 and TZM-Luc cells) and in preactivated PBMCs with either X4-tropic (NL4.3 and NL4.3-Ren) or R5-tropic (HIVBal and JR-Ren) HIV-1. In addition, the potential effect of 5-hydroxytyrosol on DC-SIGN trans-infection was also tested using RAJI-DC-SIGN cells cocultured with preactivated PBMCs. Cell viability was measured in parallel with all these conditions.

5-Hydroxytyrosol displayed a clear-cut anti-HIV activity in all the cell types (Fig. 1). Moreover, 5-hydroxytyrosol diminished virus replication in infections performed with either X4-tropic or R5-tropic HIV-1 in the medium micromolar range.

Fig. 1.

(a) Evaluation of the anti-HIV activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol in MT-2 cells, TZM-Luc cells and human primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells preactivated with PHA/interleukin-2.

Cells were infected with wild-type X4-tropic HIV (NL4.3), wild-type R5-tropic HIV (HIVBal), X4-tropic recombinant HIV (NL4.3-Ren) or with R5-tropic recombinant virus (JR-Ren). Cell viability was measured in the same conditions as infections in mock-infected cells. Data obtained were analysed using GraphPad Prism software (nonlinear regression, log inhibitor vs. response) and inhibitory concentration 50% values and confidence intervals (CIs) are shown in the table. IC50, inhibitory concentration 50%; CC50, cytotoxic concentration 50%; ND, not determined. CIs 95% are shown between brackets. (b) Evaluation of the anti-HIV activity in DC-SIGN-mediated transfection. RAJI-DC-SIGN cells were treated with 5-hydroxytyrosol at different concentrations for 1 h. Afterwards, HIV (JR-Ren) was added, left in culture for 2 h and cocultured with PHA/interleukin-2 preactivated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Forty-eight hours later, cell cultures were lysed, and Renilla-luciferase activity was measured in a luminometre. A nontreated control was considered 100%. RLUs, relative luminescence units; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Although inhibitory concentration 50% values were similar, 5-hydroxytyrosol seemed to be slightly more potent in MT-2 (with inhibitory concentrations 50% between 34 and 36 μmol/l) than in PBMCs infections (inhibitory concentrations 50% values between 42 and 58 μmol/l). 5-Hydroxytyrosol activity was not due to cell death, as it lacked cell toxicity up to 250 μmol/l in PBMCs and it reduced cell viability in cell lines only more than 125 μmol/l. Finally, 5-hydroxytyrosol activity was not due to a nonspecific effect of the detection method as it inhibited the replication of both recombinant and wild-type HIV using two different detection systems, that is Renilla-luc activity and p24 Gag production.

5-Hydroxytyrosol was tested also in DC-SIGN-mediated infections, one of the main pathways involved in HIV of infection in vivo. To do that, a cell line stably transfected with DC-SIGN receptor, RAJI-DC-SIGN, was used. As shown in Fig. 1, b1, 5-hydroxytyrosol inhibited the infections mediated by a RAJI-DC-SIGN cell line.

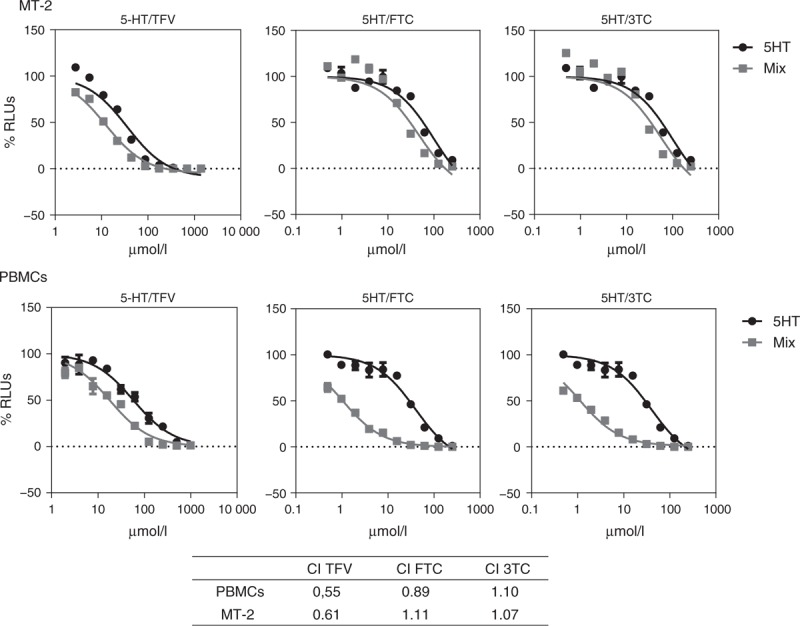

5-Hydroxytyrosol combination with TFV and FTC and 3TC shows synergy/additive effect in HIV-1 infection of PBMCs and MT-2 cells. The only preventive treatment that showed clinical efficacy as a microbicide against HIV-1 infection thus far was TFV and FTC [3,19]. Thus, in-vitro combination experiments using 5-hydroxytyrosol and TFV or FTC and 3TC were performed in MT-2 cells and preactivated PBMCs.

As shown in Fig. 2, combination indices for 5-hydroxytyrosol and TFV combinations were around 0.6 for all the scenarios tested, infection in MT-2 cells or preactivated PBMCs with PHA/interleukin-2. Thus, combination of TFV and 5-hydroxytyrosol in vitro shows a strong synergy. On the other hand, combination of 5-hydroxytyrosol with FTC or 3TC resulted only in additive effects and even in a moderate antagonism, with combination indices around 1.

Fig. 2.

Combination effect in anti-HIV activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol and tenofovir or emtricitabine or lamivudine in MT-2 cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells preactivated with PHA/interleukin-2 infected with NL4.3-Ren.

Combination ratio used was inhibitory concentration 50% to inhibitory concentration 50%. Combination indices’ values at CE50 were obtained using CalcuSyn software. GraphPad PRISM software was used to obtain graphs represented. Combination index more than 1.30 antagonism, 1.10–1.30 weak antagonism, 0.90–1.10 additive, 0.70–0.90 weak synergy, less than 0.70 strong synergy.

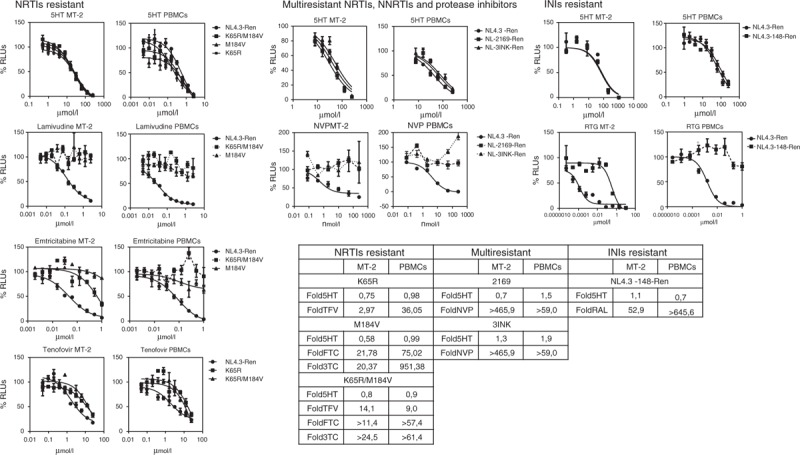

5-Hydroxytyrosol inhibits wild-type and resistant virus with the same inhibitory concentration 50%

Viral resistance is one of the main potential problems of ART, and it is of particular concern in the context of HIV prevention. Thus, we tested the anti-HIV activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol against viral clones resistant to NRTIs, NtRTIs, NNRTIs, protease inhibitors and INIs (Fig. 3). We used HIV-1 resistant to TFV (K65R), FTC (M184V) or double (K65R and M184V). Multiresistant HIV-1 pol genes amplified from infected patients were cloned into the NL4.3-Ren backbone, and the following viral clones were generated: NL4.3–2169-Ren (encompassing the following mutations: NRTI: M41L, E44D, A62V, D67E, 69ins, V118I, L210W and T215Y NNRTI: K103N and G190S and protease inhibitors: M36I, I54V, L63P, A71V, G73S and L90M) and NL4.3–3INK-Ren (encompassing the following mutations: NRTI: M41L and T215Y NNRTI: K103N and P225H PRI: L10V, L24I, M46I, I54V, L63P and V82A). 5-Hydroxytyrosol was also tested against RTG-resistant HIV-1 obtained by site-directed mutagenesis in the NL4.3-Ren backbone (Q148K).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of the anti-HIV activity 5-hydroxytyrosol in resistant HIV to NRTIs (K65R, M184V and double resistant), multiresistant HIV (NRTIs, NNRTIs and protease inhibitors) and integrase inhibitors resistant (Q148K) in infections of MT-2 cells and reactivated peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Cells were infected with wild-type X4-tropic recombinant virus NL4.3-Renilla or with resistant HIV. Data obtained were analysed using GraphPad PRISM software (nonlinear regression, log inhibitor vs. response) and inhibitory concentration 50% values calculated. Resistance fold are shown obtained by dividing inhibitory concentration 50% resistant/inhibitory concentration 50% wild-type.

As shown in Fig. 3, 5-hydroxytyrosol inhibited all these resistant viral clones with similar inhibitory concentrations 50% and comparably with wild-type viruses as the maximum fold of resistance was 1.9 with the multiresistant clone 3INK.

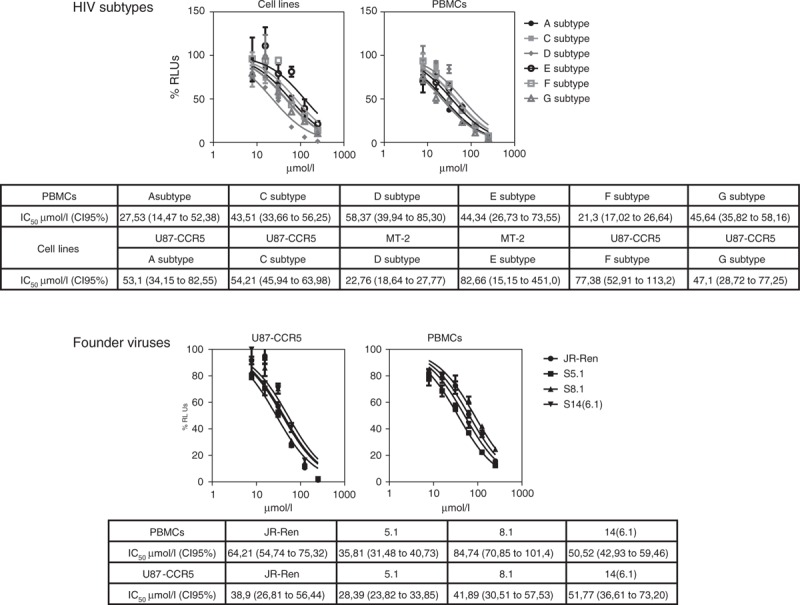

5-Hydroxytyrosol is active against different HIV subtypes and founder viruses

Ideally, a microbicide should be effective against a broad spectrum of HIV subtypes, in particular those found in low-income countries. To investigate 5-hydroxytyrosol activity on several subtypes, env gene of subtypes A, C, D, E, F and G were cloned in the NL4.3-Ren backbone and used to infect MT-2 cells (subtype X4-tropic) or U87.CD4+.CCR5 (subtype R5-tropic). Furthermore, they were all tested in PBMCs preactivated with PHA/interleukin-2. It has been claimed that transmitted-founder viruses display specific characteristics in the env gene and resistance to class I interferon, although this is a matter of debate [20]. Accordingly, microbicides should be particularly active against transmitted-founder viruses. To test the activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol against the Env from these strains, the env gene from founder viruses was amplified from patients in Fiebig III–IV stages and cloned in the NL4.3-Ren backbone.

As shown in Fig. 4, 5-hydroxytyrosol inhibited all the six different subtypes of HIV with inhibitory concentration 50% values in the same range. Moreover, 5-hydroxytyrosol was also able to inhibit replication of recombinant viruses carrying the env genes from three different transmitted-founder strains, both in human-preactivated PBMCs and in cell lines (U87.CD4+.CCR5 for A, C, F and G subtypes and all the founder viruses and MT-2 for D and E subtypes) with very similar inhibitory concentrations 50%.

Fig. 4.

5-Hydroxytyrosol activity on A, C, D, E, F and G HIV-1 subtypes and founder viruses S5.1, S8.1 and S14 (6.1) on cell lines and preactivated peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Data obtained were analysed using GraphPad PRISM software (nonlinear regression, log inhibitor vs. response) and inhibitory concentration 50% values and confidence intervals are shown in the table. IC50, inhibitory concentration 50%; CI 95%, confidence intervals at 95%.

Vaginal toxicity test in rabbits

Local 5-hydroxytyrosol toxicity was evaluated in vivo after treatment for 14 consecutive days by topical application of three doses (30, 100 and 200 mmol/l) to the rabbit vaginal mucosa. All animals were sacrificed at the end of the treatment period, and mortality/viability, clinical signs, vaginal pH and macroscopic and microscopic assessment were evaluated (Table 1).

Table 1.

In-vivo evaluation of 5-hydroxytyrosol toxicity. 5-Hydroxytyrosol was administered at three different doses for 14 consecutive days by topical route to the vaginal mucosa. All animals were sacrificed at the end of the treatment period and mortality/viability, clinical signs, microbiological assessment, vaginal pH and macroscopic and microscopic examination of the genital apparatus of each animal were performed.

| Vagina | |||||||

| Microbiological assessment | |||||||

| Clinical signs | Mortality/viability | Macroscopic examinationa | Microscopic examinationb | pH (mean ± SD) | Vaginal exudate before treatments | Vaginal mucosa after treatments | |

| Group 1: blank control (n = 6) | Swelling in the genital area for several days (n = 1) | 0 | n = 3 | LI: Grade 1 or 2 in proximal, medial and/or distal parts (n = 4) | 7.46 ± 0.30 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 6 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 0 |

| VC: Grade 1 (n = 4) | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 0 | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 4 | |||||

| E: Grade 1 (n = 2) | |||||||

| Group 2: placebo HEC gel (n = 6) | – | 0 | n = 3 | LI: Grade 1 or 2 in proximal or medial parts (n = 2) | 7.80 ± 0.48 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 6 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 0 |

| VC: Grade 1 (n = 3) | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 0 | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 1 | |||||

| E: Grade 1 (n = 2) | |||||||

| Group 3: 5-hydroxytyrosol gel 30 mmol/l (n = 6) | – | 0 | n = 4 | LI: Grade 1 or 2 in proximal, medial and/or distal parts (n = 4) | 7.73 ± 0.27 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 6 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 0 |

| VC: Grade 1 (n = 4) | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 0 | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 2 | |||||

| E: Grade 1 (n = 2) | |||||||

| Group 4: 5-hydroxytyrosol gel 100 mmol/l (n = 6) | – | 0 | n = 6 | VC: Grade 1 (n = 6) | 7.66 ± 0.39 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 5 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 1 |

| E: Grade 1 (n = 3) | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 0 | |||||

| Group 5: 5-hydroxytyrosol gel 200 mmol/l (n = 6) | – | 0 | n = 5 | LI: Grade 1 or 2 in proximal and medial parts (n = 5) | 7.55 ± 0.35 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 5 | Streptococcus sp.: n = 1 |

| VC: Grade 1 (n = 5) | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 0 | Klebsiella pneumoniae: n = 3 | |||||

| E: Grade 1 (n = 3) | |||||||

aMacroscopic examination: n means number of animals with signs of irritation in the vaginal mucosa.

bMicroscopic examination: leukocyte infiltration (LI) in vaginal mucosa. Vascular congestion (VC) on submucosa (proximal, medial and/or distal parts) and oedema (E) in mucosa (proximal, medial and/or distal parts): absent (grade 0), minimal (grade 1), mild (grade 2), moderate (grade 3) and marked (grade 4).

As shown in Table 1, no differences on body-weight evolution, clinical signs and mortality/viability were found. On the other hand, macroscopic examination showed slightly to moderately reddish vaginal mucosa in medial, proximal and/or distal areas (mainly in distal area) in more animals for 5-hydroxytyrosol-treated groups, but without evident dose–effect correlation as compared with placebo or non-5-hydroxytyrosol gel. Cell culture of the vaginal exudates revealed presence of the following bacteria in the flora of the vagina: Escherichia coli, Streptococcus sp., Staphylococcus sp., Gram positive Bacillus, Pasteurella sp. and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Streptococcus sp. was present in almost all the animals before treatment. After 14 days of administration, the presence of Streptococcus sp. decreased in the majority of animals. No correlations were observed between 5-hydroxytyrosol treatment and changes in terms of microorganism's detection.

Conclusion

In this study, we have investigated 5-hydroxytyrosol as a potential microbicide candidate. 5-Hydroxytyrosol is a natural compound with antioxidant [21], anti-inflammatory [22,23] and antiviral properties [8–10]. We show here that 5-hydroxytyrosol inhibits HIV-1 replication with inhibitory concentrations 50% in the micromolar range. Its anti-HIV activity seems to be one order of magnitude higher than data provided by previous literature [8–10]. Nevertheless, those studies were exclusively based on enzymatic assays or docking studies of interaction with gp41 Env glycoprotein. Our results show that inhibitory concentration 50% of 5-hydroxytyrosol is between 30 and 60 μmol/l depending on the virus strain and cells used.

A microbicide has to be effective in the mucosal environment, in which infections are in part due to the exposure of HIV to CD4+ lymphocytes by DC-SIGN+ cells [24]. 5-Hydroxytyrosol antiviral activity is not only maintained but it was actually increased in a DC-SIGN-dependent environment (as shown in Fig. 1), thereby increasing its interest as microbicide. To fully characterize the activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol, other contexts of viral infection such as transcytosis, cell-to-cell transmission or SIGLEC1-mediated transmission should be explored [25].

Although 5-hydroxytyrosol inhibitory concentrations 50% values could be considered ‘high’ for a drug candidate, as a low oral bioavailability could hamper its antiviral effect, previous reports show that 5-hydroxytyrosol oral bioavailability is close to 99% when isotopic labelled 5-hydroxytyrosol was used [21]. In addition, microbicides are used topically, applied directly in vaginal mucosae, which would bypass any problem derived from first pass effect and will yield higher concentrations in the site of action. On the other hand, one of the microbicides clinical assays showing medium efficacy in HIV infection protection, the CAPRISA004 study, was based on an antiretroviral drug, TFV, with inhibitory concentrations 50% also in the micromolar range.

An ideal microbicide would inhibit all the possible HIV strains. To evaluate anti-HIV activity spectra, we tested 5-hydroxytyrosol against drug-resistant HIV. 5-Hydroxytyrosol inhibits infection of HIV clones resistant to almost all the antiretroviral drugs approved, NRTIs, NtRTIs, NNRTIs, protease inhibitors and INIs (Fig. 3). HIV strains used to evaluate antiviral activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol are included in the B subtype, the dominant form in west and central Europe, the Americas, Australia, South America, and several southeast Asian countries (Thailand and Japan) as well as northern Africa and the Middle East. However, microbicides are conceived to be used particularly in countries with limited resources, as sub-Saharan Africa, in which subtype C is the predominant one. Therefore, we have tested 5-hydroxytyrosol against infections with different subtypes, including HIV found in the early stages after infection (founder viruses). 5-Hydroxytyrosol inhibited all the strains tested in both cell lines and primary preactivated PBMCs (Fig. 4) with similar inhibitory concentrations 50%, suggesting that 5-hydroxytyrosol would be a wide-range HIV inhibitor and an excellent microbicide candidate.

ART includes drug cocktails including at least one NRTI and one NtRTIs or NNRTI, as monotherapy leads invariably to resistance emergence. Microbicides could contain also more than one antiretroviral drug but some combinations are not allowed due to antagonism between antiretroviral drugs [26]. Therefore, we have tested 5-hydroxytyrosol combinations with TFV, 3TC and FTC, drugs usually included in microbicide formulations. 5-Hydroxytyrosol showed a clear synergistic effect with TFV and an additive effect with 3TC and FTC, and thus combinations with these drugs would be likely effective (Fig. 2) and could be used to develop a new microbicide formulation.

Lastly, toxicity of microbicides has always been a cause of concern as some of them increased the risk of HIV-1 infection due to abrasive or proinflammatory effects. There is a long history of failed clinical trials on microbicides, due mainly to safety concerns. Detergents such nonoxynol-9 or cellulose sulphate were vaginal mucosa irritating or proinflammatory agents, leading to an increase in HIV infection rates [27]. 5-Hydroxytyrosol showed evidence of cytotoxicity only at very high concentrations in human PBMCs or in the MT-2 cell lines (>250 μmol/l). Moreover, topical route administration of 5-hydroxytyrosol on the rabbit vagina mucosa showed little or no toxicity at all in a classic model of in-vivo toxicity evaluation. These results were not surprising to us on the basis of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of 5-hydroxytyrosol that has already been described independently [23,28,29]. Also in previous clinical assays, there was no evidence of significant toxicity [30]. Although we have not included nonoxynol-9 as a positive control in our in-vivo toxicity study, other authors have done it previously with similar methodology to assess spermicide activity. In rabbits treated with nonoxynol-9 as positive control, erosion of the vaginal epithelial lining, marked leukocyte infiltration, haemorrhage, decreased epithelial cell-height and necrosis of the vaginal epithelium were obtained [31].

In summary, 5-hydroxytyrosol encompasses several features of an ideal microbicide as it is stable, easily formulable, cheap and nontoxic in a wide range of experimental situations. All these findings together make 5-hydroxytyrosol of great interest as a potential component of novel microbicide formulations to prevent heterosexual HIV-1 transmission via the vaginal mucosa.

Acknowledgements

AIM-HIV Network of Excellence of the EU, grant number HEALTH-F3-2012-305938. CHAARM European Community's Seventh Framework programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 242135. Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Intrasalud PI12/0056). The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: tenofovir, lamivudine, emtricitabine, nevirapine and raltegravir.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). AIDS by the numbers [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. CAPRISA 004 Trial Group. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science 2010; 329:1168–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. iPrEx Study Team. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. VOICE Study Team. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:509–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2015: Abstracts 22LB and 23LB. Presented February 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, Blechinger D, Nguyen DP, Follansbee S, Hare CB. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1601–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Zhang D, Lee JW, Bao J, Sun Y, et al. Discovery of small-molecule HIV-1 fusion and integrase inhibitors oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol: Part II. Integrase inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 354:879–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Zhang D, Lee JW, Bao J, Sun Y, et al. Discovery of small-molecule HIV-1 fusion and integrase inhibitors oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol: Part I. Fusion [corrected] inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 354:872–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao J, Zhang DW, Zhang JZ, Huang PL, Huang PL, Lee-Huang S. Computational study of bindings of olive leaf extract (OLE) to HIV-1 fusion protein gp41. FEBS Lett 2007; 581:2737–2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koening S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol 1988; 59:284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Perez J, Sanchez-Palomino S, Perez-Olmeda M, Fernandez B, Alcami J. A new strategy based on recombinant viruses as a tool for assessing drug susceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Med Virol 2007; 79:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González N, Pérez-Olmeda M, Mateos E, Cascajero A, Alvarez A, Spijkers S, et al. A sensitive phenotypic assay for the determination of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tropism. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:2493–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuevas MT, Fernández-García A, Pinilla M, García-Alvarez V, Thomson M, Delgado E, et al. Biological and genetic characterization of HIV type 1 subtype B and nonsubtype B transmitted viruses: usefulness for vaccine candidate assessment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2010; 26:1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenyo EM, Heath A, Dispinseri S, Holmes H, Lusso P, Zolla-Pazner S, et al. International network for comparison of HIV neutralization assays: the NeutNet report. PLoS One 2009; 4:e4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, Garrett PE, Schumacher RT, Peddada L, et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS 2003; 17:1871–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Perez J, Perez-Olmeda M, Sanchez-Palomino S, Perez-Romero P, Alcami J. A new strategy based on recombinant viruses for assessing the replication capacity of HIV-1. HIV Med 2008; 9:160–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-Avila O, Bedoya LM, Marradi M, Clavel C, Alcamí J, Penadés S. Multivalent manno-glyconanoparticles inhibit DC-SIGN-mediated HIV-1 trans-infection of human T cells. Chembiochem 2009; 10:1806–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of preexposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parrish NF, Gao F, Li H, Giorgi EE, Barbian HJ, Parrish EH, et al. Phenotypic properties of transmitted founder HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:6626–6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilaplana-Pérez C, Auñón D, García-Flores LA, Gil-Izquierdo A. Hydroxytyrosol and potential uses in cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and AIDS. Front Nutr 2014; 1:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Incani A, Deiana M, Corona G, Vafeiadou K, Vauzour D, Dessì MA, Spencer JP. Involvement of ERK, Akt and JNK signalling in H2O2-induced cell injury and protection by hydroxytyrosol and its metabolite homovanillic alcohol. Mol Nutr Food Res 2010; 54:788–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva S, Sepodes B, Rocha J, Direito R, Fernandes A, Brites D, et al. Protective effects of hydroxytyrosol-supplemented refined olive oil in animal models of acute inflammation and rheumatoid arthritis. J Nutr Biochem 2015; 26:360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Middel J, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 2000; 100:587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izquierdo-Useros N, Lorizate M, McLaren PJ, Telenti A, Kräusslich HG. HIV-1 capture and transmission by dendritic cells: the role of viral glycolipids and the cellular receptor Siglec-1. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Olmeda M, Garcia-Perez J, Mateos E, Spijkers S, Ayerbe MC, Carcas A, et al. In vitro analysis of synergism and antagonism of different nucleoside/nucleotide analogue combinations on the inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Med Virol 2009; 81:211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdool Karim SS, Baxter C. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: future implementation challenges. HIV Therapy 2009; 3:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granados-Principal S, El-Azem N, Pamplona R, Ramirez-Tortosa C, Pulido-Moran M, Vera-Ramirez L, et al. Hydroxytyrosol ameliorates oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats with breast cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 2014; 90:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva S, Sepodes B, Rocha J, Direito R, Fernandes A, Brites D, et al. Protective effects of hydroxytyrosol-supplemented refined olive oil in animal models of acute inflammation and rheumatoid arthritis. J Nutr Biochem 2015; 26:360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verhoeven V, Van der Auwera A, Van Gaal L, Remmen R, Apers S, Stalpaert M, et al. Can red yeast rice and olive extract improve lipid profile and cardiovascular risk in metabolic syndrome?: A double blind, placebo controlled randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015; 15:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain A, Kumar L, Kushwaha B, Sharma M, Pandey A, Verma V, et al. Combining a synthetic spermicide with a natural trichomonacide for safe, prophylactic contraception. Hum Reprod 2014; 29:242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]