Abstract

With the advent of next-generation sequencing, an increasing number of novel gene fusions and other abnormalities have emerged recently in the spectrum of EWSR1-negative small blue round cell tumors (SBRCTs). In this regard, a subset of SBRCTs harboring either BCOR gene fusions (BCOR-CCNB3, BCOR-MAML3), BCOR internal tandem duplications (ITD), or YWHAE-NUTM2B share a transcriptional signature including high BCOR mRNA expression, as well as similar histologic features. Furthermore, other tumors such as clear cell sarcoma of kidney (CCSK) and primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy (PMMTI) also demonstrate BCOR ITDs and high BCOR gene expression. The molecular diagnosis of these various BCOR genetic alterations requires an elaborate methodology including custom BAC FISH probes and RT-PCR assays. As these tumors show high level of BCOR overexpression regardless of the genetic mechanism involved, either conventional gene fusion or ITD, we sought to investigate the performance of an anti-BCOR monoclonal antibody clone C-10 (sc-514576) as an immunohistochemical marker for sarcomas with BCOR gene abnormalities. Thus we assessed the BCOR expression in a pathologically and genetically well-characterized cohort of 25 SBRCTs, spanning various BCOR-related fusions and ITDs and YWHAE-NUTM2B fusion. In addition we included related pathologic entities such as 8 CCSKs and other sarcomas with BCOR gene fusions. As a control group we included 20 SBRCT with various (non-BCOR) genetic abnormalities, 10 fusion-negative SBRCT, 74 synovial sarcomas, 29 rhabdomyosarcoma and other sarcoma types. Additionally we evaluated the same study group for SATB2 immunoreactivity, as these tumors also showed SATB2 mRNA up-regulation. All SBRCTs with BCOR-MAML3 and BCOR-CCNB3 fusions, as well as most with BCOR ITD (93%), and all CCSKs showed strong and diffuse nuclear BCOR immunoreactivity. Furthermore, all SBRCTs with YWHAE-NUTM2B also were positive. SATB2 stain was also positive in tumors with YWHAE-NUTM2B, BCOR-MAML3, BCOR ITD (75%), BCOR-CCNB3 (71%), and a subset of CCSKs (33%). In conclusion, BCOR immunohistochemical stain is a highly sensitive marker for SBRCTs and CCSKs with BCOR abnormalities and YWHAE rearrangements and can be used as a useful diagnostic marker in these various molecular subsets. SATB2 immunoreactivity is also present in the majority of this group of tumors.

Keywords: small blue round cell tumor, clear cell sarcoma kidney, synovial sarcoma, BCOR, SATB2, YWHAE, immunohistochemistry

INTRODUCTION

Round cell sarcomas encompass a heterogeneous group of tumors, which, despite similar cytomorphology of primitive small blue round cells, have diverse genetic abnormalities, clinical presentations and outcomes. Until recently, a substantial subset of tumors resembling Ewing sarcoma microscopically and occurring in children or young adults remained unclassified, lacking known gene fusions involving EWSR1, FUS, SS18, FOXO1, etc. As a result of the wide application of next generation sequencing to undifferentiated round cell sarcomas, an increasing number of novel genetic abnormalities have been identified including: CIC-DUX4, CIC-FOXO4, BCOR-CCNB3, BCOR-MAML3, ZC3H7B-BCOR, YWHAE-NUTM2B gene fusions or BCOR internal tandem duplication (ITD).1-6 However, the diagnosis of these emerging entities relies largely on elaborate molecular tests, such as FISH, RT-PCR or genomic PCR, which are not widely available. Although the use of immunohistochemical markers remains a more practical approach to screen and support the diagnosis in this setting, there are only a handful of antibodies available which can be reliably used in the differential diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma-like tumors. Two such examples include the consistent nuclear expression of WT1 in CIC-DUX4 positive small blue round cell tumors (SBRCTs)7 and the CCNB3 nuclear overexpression in BCOR-CCNB3 positive tumors.4,8,9 Although most SBRCTs harboring either BCOR genetic abnormalities or YWHAE fusions show significant BCOR mRNA up-regulation,6,10,11 no BCOR immunohistochemical marker has been investigated to date in this molecular subset of tumors. BCOR protein expression has been demonstrated by immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry in a small number of CCSKs.10,11 Based on our previous findings of BCOR and SATB2 up-regulation in round cell sarcomas with BCOR ITD, YWHAE-NUTM2B, and BCOR-MAML3 fusions by RNA sequencing,6 we sought to investigate the sensitivity and specificity of BCOR and SATB2 antibodies in this well-defined molecular cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case selection

Round cell sarcomas with BCOR ITD (n=14; 8 undifferentiated round cell sarcoma, 6 primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy), YWHAE-NUTM2B (n=2), BCOR-CCNB3 (n=8), and BCOR-MAML3 (n=1) gene fusions were collected from the consultation archives of the corresponding author (CRA), most being previously reported.5,6 All 16 tumors with BCOR ITD or YWHAE-NUTM2B occurred in infants (age: 10 days to 11 months old) and involved abdominopelvic cavity/ retroperitoneum (n=6), trunk (n=7) and head and neck (n=3). Among the 8 BCOR-CCNB3 tumors, 5 arose in bone (2 pelvis, 2 femur, 1 tibia) and 3 in the soft tissues (2 paraspinal, 1 chest wall), with an age range of 10-21 years. The BCOR-MAML3 tumor occurred as a bulky intra-abdominal mass in a 44 year-old male patient. In addition, we investigated 8 CCSKs, 4 harboring BCOR ITD and 1 YWHAE-NUTM2B/E fusion. The remaining 3 CCSKs lacking both genetic abnormalities showed typical histomorphology and age at presentation (10 months, 19 months, and 5 years, respectively). Three other tumors harboring ZC3H7B-BCOR fusion were tested, including 2 endometrial stromal sarcomas and 1 ossifying fibromyxoid tumor. Within the control group, there were 8 Ewing sarcomas with EWSR1-FLI1 fusion, 1 Ewing sarcoma-like with EWSR1-NFATC2 fusion, 6 SBRCTs with CIC gene rearrangements, 5 desmoplastic small round cell tumors (DSRCTs) with EWSR1-WT1 fusion, 10 SBRCTs lacking known genetic abnormalities, and 3 poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas with SS18 gene fusions. All of the above cases were tested using whole-tissue sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues.

To further investigate the specificity of the BCOR antibody, we screened a large spectrum of soft tissue tumors, using tissue microarrays (TMA) of synovial sarcoma (n=71), rhabdomyosarcoma (n=29), angiosarcoma (n=41), low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (n=14), chondrosarcoma (n=41), and myxofibrosarcoma (n=92). The fusion transcript types were known in a subset of synovial sarcomas, including 18 SS18-SSX1 and 16 SS18-SSX2 fusion cases.

Immunohistochemical BCOR protein expression analysis

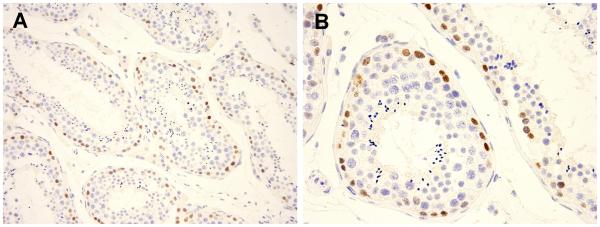

Immunohistochemical staining for BCOR was performed in all cases. A commercially available antibody, clone C10 (sc-514576; Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) was used for the immunohistochemical analysis. The antibody was generated against the N-terminus (1-300 amino acid) of BCOR. The antibody was optimized using normal and molecularly pre-typed tumor tissues. All assays were performed on a Leica Bond-3 autostainer platform (Leica, Buffalo Grioe, IL). C-10 worked best at a dilution of 1:150 (1.7ug/ml), employing heat-based antigen retrieval, using a high pH buffer solution (Leica, ER2, 30’) and a primary incubation time of 30 minutes. A polymer-based secondary system (Refine, Leica) was used to detect the primary reagent. A carrier-based multi tissue block comprising of a variety of normal tissues (spleen, placenta, kidney, colon, liver, skin, pancreas, testis, and lung) as well as tumor tissue sections were used during the antibody optimization stage and as controls.12 For example, spermatogonia in the seminiferous tubules were found to show distinct nuclear stain in a clean background corresponding to the BCOR mRNA expression in normal tissues (Fig. 1). Other tissues were used as negative controls.

Figure 1. BCOR immunostaining positive control in testis.

BCOR nuclear positivity in the spermatogonia within the seminiferous tubules (A, 200X; B, 400X).

The results were evaluated based on the intensity (strong, moderate, weak, and negative) and the estimated percentage of positive tumor cells. Only nuclear stain was counted. Tumors with moderate to strong staining intensity in more than 10% of the tumor were considered positive.

Immunohistochemical SATB2 protein expression analysis

SATB2 immunoreactivity was evaluated in a subset of cases using whole sections, including round cell sarcomas with BCOR ITD (n=12), YWHAE-NUTM2B (n=2), BCOR-MAML3 (n=1), BCOR-CCNB3 (n=7), CCSKs (n=6), and poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas (n=2). Additionally, we tested this antibody on TMA sections of synovial sarcoma (n=73) and rhabdomyosarcoma (n=29). Monoclonal rabbit antibody clone EP281 (1:200; CellMarque, California, USA) was used for the detection of SATB2. As with C-10, the staining was performed on Leica (Bond-3) automated staining system (Leica), employing heat-based antigen retrieval (ER2, Leica, 30’) and a polymer (Leica, Refine) detection system (Leica). Normal colonic mucosa served as positive control throughout. Only nuclear stain was considered positive. The results were recorded as described above.

Gene expression array and transcription factor motif analysis

To investigate the mechanism of BCOR up-regulation in round cell sarcomas with BCOR abnormalities or YWHAE fusions, we analyzed the overexpressed transcription factors (TFs) in these tumors for potential binding sites to the BCOR gene promoter area (3 KB upstream from the transcription start site). Among the 404 differentially expressed gene signature of BCOR ITD tumors by RNA sequencing,6 there were 64 genes labeled as TF or TF-related genes, which were then searched for known motif sequences using available TF motifs databases (HOCOMOCO, motifDB, and factorbook tools).

Due to unexpected BCOR immunoreactivity in a subset of synovial sarcomas, we further analyzed the gene expression profiles of synovial sarcoma from publicly available array data and compared them to the signature of BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas and Ewing sarcomas, available on the same platform. Datasets from 34 synovial sarcomas (GSE20196), 10 BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas (GSE34800), and 4 Ewing sarcomas (GSE34800) on Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Plus 2 were obtained.4,13 The data analysis of the 34 synovial sarcomas was also investigated in relationship to the histologic subtype (monophasic, biphasic and poorly differentiated) according to the information provided.13 For comparison, we included the expression data of normal human tissues and non-sarcomatous tumoral tissues (randomly selected samples from GSE16515,14 GSE50161,15 GSE7307). After the signal intensities were log2-transformed, the expression levels of BCOR and SATB2 in these samples were evaluated and compared to the round cell sarcomas with BCOR abnormalities or YWHAE fusions and CCSKs. Statistical t-test and false discovery rate (FDR) were applied to identify differentially expressed genes in synovial sarcomas comparing to the control group, using a threshold of log2 fold change negative 5 or positive 2 with 0.01 FDR. A similar approach was then used to identify possible TFs leading to high BCOR expression in synovial sarcomas. In addition, as both SSX1 (Xp11.23) or SSX2 (Xp11.22) and BCOR (Xp11.4) are located on the p-arm of chromosome X, we investigated the expression of neighboring genes within a 21.8 MB region (chr X: 31,000,000-52,792,617) for potential coupled upregulation.

RESULTS

Strong and diffuse BCOR immunoexpression across all sarcomas with BCOR-genetic abnormalities

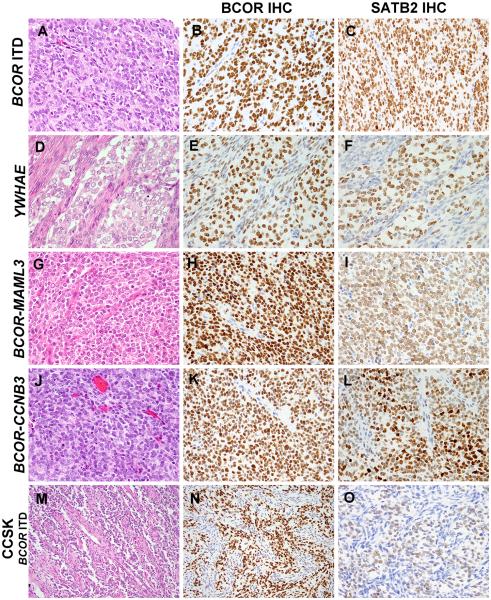

The results of BCOR immunohistochemical stains are summarized in Table 1. All SBRCTs with BCOR ITD, YWHAE-NUTM2B, BCOR-MAML3 and BCOR-CCNB3 fusions showed nuclear expression of BCOR (Fig. 2), except for one BCOR ITD-positive tumor. The staining patterns were typically strong and diffuse, except for 2 cases in the BCOR ITD group showing moderate intensity and patchy staining (60% in an abdominal wall mass of a 9 month-old female and 30% in a cauterized specimen from a paravertebral mass of a 10 month-old male). Regardless of the cytomorphologic features (round, stellate or spindle cells), the staining pattern was diffuse. Rich capillary network and occasional fibrous septa in these tumors were distinctively negative, serving as internal negative controls. The only BCOR ITD SBRCT negative for BCOR immunohistochemical stain occurred in an 11 month-old male with a thoracic mass. The presence of BCOR ITD was re-confirmed by PCR using genomic DNA from FFPE tissues, but no material was available for mRNA expression analysis.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical protein expression analysis of BCOR (clone C-10) and SATB2 (clone EP281)

| Tumor type | BCOR | SATB2 |

|---|---|---|

| Round cell sarcoma | ||

| BCOR ITD | 13/14 (92.9%) | 9/12 (75%) |

| YWHAE-NUTM2B | 2/2 (100%) | 2/2 (100%) |

| BCOR-MAML3 | 1/1 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| BCOR-CCNB3 | 8/8 (100%) | 5/7 (71.4%) |

| CIC rearrangement | 1/6 (16.7%) | ND |

| EWSR1-FLI1/NFATC2 | 1/9 (11.1%) | ND |

| DSRCT | 0/5 (0%) | ND |

| Unknown/Fusion neg. | 2/10 (20%) | ND |

| Clear cell sarcoma of kidney | ||

| Total | 8/8 (100%) | 2/6 (33.3%) |

| BCOR ITD | 4/4 (100%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| YWHAE-NUTM2B | 1/1 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| Wild type for both | 3/3 (100%) | 0/2 (0%) |

| Synovial sarcoma | ||

| Overall (TMA*+PD) | 35/74 (49.3%) | 9/75 (12%) |

| Monophasic* | 7/20 (35%) | 2/20 (10%) |

| Biphasic* | 5/14 (35.7%) | 1/15 (6.7%) |

| SYT-SSX1 * | 5/18 (27.8%) | 3/19 (15.8%) |

| SYT-SSX2 * | 7/16 (43.8%) | 0/16 (0%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 3/3 (100%) | 2/2 (100%) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma * | 2/29 (6.9%) | 0/29 (0%) |

| Angiosarcoma * | 0/41 (0%) | ND |

| Myxofibrosarcoma * | 1/92 (1.1%) | ND |

| Chondrosarcoma * | 0/41 (0%) | ND |

| LGFMS * | 0/14 (0%) | ND |

| ESS with ZC3H7B-BCOR | 0/2 (0%) | ND |

| OFMT with ZC3H7B-BCOR | 0/1 (0%) | ND |

Immunohistochemical stains performed on tissue microarray.

ITD: internal tandem duplication; DSRCT: desmoplastic small round cell tumor; neg.: negative; TMA: tissue microarray; PD: poorly differentiated; LGFMS, low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma; ESS, endometrial stromal sarcoma; OFMT, ossifying fibromyxoid tumor; ND, not done.

Figure 2. Diffuse BCOR and SATB2 immunoreactivity in round cell sarcomas with BCOR abnormalities, YWHAE-NUTM2B fusion, and CCSK.

Round cell sarcomas with BCOR ITD and YWHAE-NUTM2B show uniform round cells with fine chromatin pattern and rich fibrovascular background (A, D) and exhibit diffuse and strong nuclear expression of BCOR (B, E), and strong (C) to moderate (F) SATB2 staining. SBRCT with BCOR-MAML3 and BCOR-CCNB3 fusions show diffuse sheets of round to ovale cells with fine chromatin (G, J) and demonstrate strong nuclear expression of BCOR (H, K), while SATB2 had strong to moderate (I) intensity and greater degree of intratumoral heterogeneity (L) compared to BCOR stain. CCSK harboring BCOR ITD has similarly uniform round cells (M) and displayed strong BCOR staining (negative fibrovascular septa)(N), whereas SATB2 expression was weak (O).

Ewing sarcomas and CIC-rearranged tumors were negative, with only one case in each group showing patchy moderate nuclear positivity (Supplementary Fig. 1). DSRCTs were also negative. Interestingly, among the 10 undifferentiated round cell sarcomas lacking known gene fusions, 2 cases were diffusely and strongly immunopositive for BCOR (Supplementary Fig. 2). One of them occurred in a 1 year-old female presenting with an orbital mass, which was negative for all immunostains tested including CD99, desmin, myogenin, TdT, CD45, etc. Morphologically, it showed diffuse sheets of monomorphic small blue round cells in a vascular-rich background. It was negative for EWSR1, FUS, CIC, YWHAE, BCOR and SS18 gene abnormalities by FISH as well as for BCOR ITD by PCR. The other case was a 16 year-old male patient with a retroperitoneal mass and liver metastasis. Histologically, it showed a round cell sarcoma with focal spindling and focal stromal hyalinization. It was negative for EWSR1, FUS, CIC, YWHAE, BCOR and SS18 gene rearrangements by FISH.

All 8 CCSKs showed moderate to strong BCOR immunoreactivity (Fig. 2N), regardless of the genetic alterations, including BCOR ITD, YWHAE fusion or wild type for both. Cellular fibrous septa and capillaries were negative. Adjacent normal renal parenchyma was also negative.

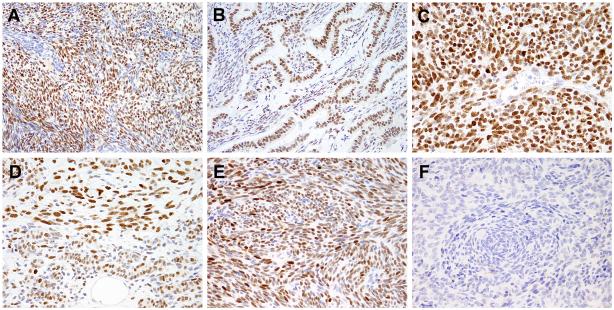

A subset of synovial sarcoma shows BCOR immunoreactivity

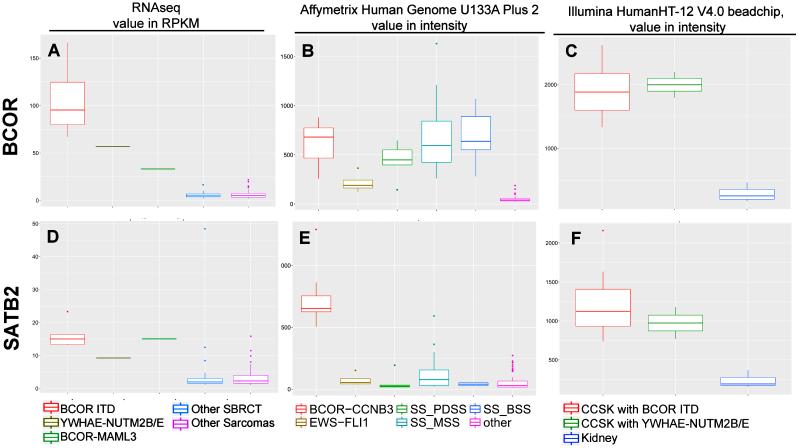

We evaluated 71 synovial sarcomas on TMA and 3 additional poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas, which could mimic other round cell sarcomas, on whole-tissue sections. Overall, 49% of synovial sarcomas had moderate to strong BCOR positivity in more than 10% of the tumor (Fig. 3). All 3 poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas had diffuse and strong BCOR staining (Fig. 3C), while the 71 cases on TMA showed variable BCOR staining, ranging from negative (n=39), moderate (n=16) to strong (n=16) staining. A subset of synovial sarcomas had available information regarding the histologic subtypes as monophasic or biphasic, the fusion variants as SS18-SSX1 or SS18-SSX2 and patient genders. The immunoreactivity did not correlate with any of these factors (Table 1). In biphasic synovial sarcomas, the staining was noted in both the epithelial and spindle cell components (Fig. 3B, D). To investigate if the BCOR protein overexpression noted in half of the synovial sarcomas is related to transcriptional up-regulation, we analyzed the expression array data from the published synovial sarcoma dataset and found high BCOR mRNA levels across monophasic, biphasic and poorly differentiated subtypes, similar to other tumors harboring BCOR gene alterations (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. BCOR staining in synovial sarcomas.

BCOR nuclear immunoreactivity was present in all histologic subtypes of synovial sarcoma, including monophasic (A), biphasic (B) and poorly differentiated (C), and fusion types, including SS18-SSX1 (D) and SS18-SSX2 (E). In biphasic tumors, BCOR expression was stronger in either epithelial (B) or spindle cell component (D). About half of synovial sarcoma cases are negative for BCOR (F).

Figure 4. BCOR and SATB2 transcriptional up-regulation is a consistent feature of SBRCT with BCOR gene abnormalities.

By RNA sequencing, SBRCTs with BCOR ITD, YWHAE-NUTM2B, and BCOR-MAML3 showed BCOR mRNA upregulation compared to other SBRCT and other sarcomas (A).6 Using different publicly available datasets, BCOR mRNA expression is also up-regulated in BCOR-CCNB3 tumors as well as in all synovial sarcomas histologic subtypes (PDSS, poorly differentiated; MSS, monophasic; BSS, biphasic) by Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Plus 2 platform, as compared to Ewing sarcoma (EWSR1-FLI1) and other non-sarcomatous tumors and normal tissues (other)(B).4,13-15 By Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 beadchip, CCSK with BCOR ITD and YWHAE-NUTM2B fusion also showed high BCOR mRNA compared to normal kidney tissues.16 In contrast, SATB2 mRNA up-regulation was seen in all SBRCTs with BCOR genetic abnormalities and CCSK, but not in synovial sarcomas (D-F).

BCOR is not expressed in most other sarcoma types

Most other sarcoma types tested were negative for BCOR, with only 2 of 29 rhabdomyo-sarcomas (1 alveolar, 1 embryonal) and 1 of 92 myxofibrosarcomas showed moderate BCOR staining. No staining was found in any of the chondrosarcomas, low grade fibromyxoid sarcomas, and angiosarcomas TMAs. Furthermore, no BCOR reactivity was noted in the 3 cases harboring ZC3H7B-BCOR fusion (2 endometrial stromal sarcoma and 1 ossifying fibromyxoid tumor).

SATB2 overexpression in sarcomas with BCOR gene abnormalities

SATB2 immunoexpression was assessed in the same study group based on the significant SATB2 mRNA upregulation in the BCOR-ITD genomic group and the availability of a commercial antibody against SATB2. SATB2 positivity was present in the majority of round cell sarcomas harboring BCOR ITD (75%), YWHAE-NUTM2B (100%), BCOR-MAML3 (100%), and BCOR-CCNB3 (71%) (Fig. 2; Table 1). However, compared to the BCOR staining pattern, SATB2 showed increased intratumoral heterogeneity in the intensity of staining. CCSK also showed variable SATB2 immunohistochemical expression. Two of 6 CCSKs tested were positive (one BCOR ITD and one YWHAE fusion), with intratumoral heterogeneity being observed.

SATB2 immunostaining is inconsistent in synovial sarcoma

As BCOR immunoreactivity was present in synovial sarcomas and rare rhabdomyo-sarcomas, we also evaluated SATB2 expression in these 2 additional cohorts. The results showed that only a minority of synovial sarcoma (n=9, 12%) expressed SATB2 immunohistochemically. However, both of the poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas with round cell histomorphology examined in whole-tissue sections were positive. Co-expression of BCOR and SATB2 stains was observed in 7 out of 9 cases. No SATB2 mRNA up-regulation was noted in synovial sarcomas (Fig. 4). No SATB2 reactivity was observed in the rhabdomyosarcoma TMA.

Gene signature and potential transcription factors regulating BCOR expression in tumors with BCOR genetic abnormalities and synovial sarcoma

As reported previously, we have obtained the gene signature of round cell sarcomas/ PMMTI with BCOR ITD and YWHAE-NUTM2B by RNA sequencing,6 of CCSKs by Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 beadchip,16 and of BCOR-CCNB3 tumors by Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Plus 2 platform.4 Forty-four genes, including BCOR and SATB2, were similarly up-regulated in all of them. In this study, we also investigated overexpressed TFs for potential roles in transcriptional upregulation of BCOR. Thus we searched the TF motif databases for known motif sequences of differentially expressed TFs in the BCOR ITD tumors, which could target the BCOR promoter region. We identified 19 TFs, each with one or more possible motifs in the BCOR promoter region, including ELF2, HES7, ETV5, YWHAZ, INSM1, SOX9 (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Figure 3).

We have performed a similar analysis in synovial sarcoma. Among the 411 differentially expressed genes on U133A plus 2, BCOR was significantly upregulated in all synovial sarcoma subtypes (monophasic, biphasic and poorly differentiated) (Fig. 4), which correlated with the high level of immunohistochemical expression. In keeping with the inconsistent SATB2 immunoreactivity, SATB2 mRNA expression was not up-regulated in synovial sarcoma as noted in other BCOR-positive tumors (Fig. 4). Among the 70 upregulated TF or TF-associated genes, GTF2I, MYC, MSX2, and GATA6, were found to have potential binding motifs to the BCOR promoter region (Supplementary table 1, Supplementary Figure 3). Interestingly, GATA6 was up-regulated in both synovial sarcoma and BCOR-CCNB3 tumors. Moreover, GTF2I, MSX2, and GATA6 also had binding motif sequences on the promoter region of TLE1 gene, another transcriptional corepressor up-regulated in synovial sarcoma. The GATA6 motifs on TLE1 and BCOR promoters were similar, while the motifs for GTF2I and MSX2 were different. Although there were 12 other differentially expressed TFs in common between synovial sarcomas and BCOR ITD tumors, none of them had known motifs on BCOR promoter (Supplementary table 1). Furthermore, there were no shared patterns of mRNA expression noted in the neighboring genomic region encompassing SSX1/2 and BCOR genes to suggest a common region of amplification/ up-regulation.

DISCUSSION

BCOR (BCL-6 interacting corepressor) is a transcriptional corepressor involved in suppressing gene expression by either interacting with BCL-6 or binding to PCGF1 (polycomb-group RING finger homologue 1), as part of a variant Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1), and inducing gene silencing via histone modification.17,18 In human tissues, BCOR mRNA is ubiquitously expressed in various tissues;17 however, the BCOR protein expression in adult human tissue is largely unknown. During our antibody validation, BCOR immunoreactivity was identified mainly in the testis, with scattered weak positivity in the germinal centers of tonsil, but not in other human tissues tested (spleen, placenta, kidney, colon, liver, epidermis, and pancreas).

We have recently reported a subset of soft tissue round cell sarcomas in infants harboring BCOR ITD or YWHAE-NUTM2B fusion, occurring with predilection in the trunk and abdominal cavity.6 Remarkably, these tumors share similar genetic abnormalities and histologic features with CCSK.6,19 Histologically, these lesions are characterized by uniform round cells with fine chromatin pattern and rich vascular background. Additional findings seen in a subset of cases include stellate, vacuolated or spindle cell cytomorphology, myxoid stromal change, cellular fibrous septa and rosette formation. Moreover, tumors previously designated as primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy (PMMTI) were also shown to harbor BCOR-ITD and exhibit overlapping morphology and clinical presentation.6

An additional molecular subset of SBRCT emerging recently is characterized by BCOR-related fusions, either by an intra-chromosomal X inversion, BCOR-CCNB3, or an inter-chromosomal translocation, BCOR-MAML3.4-6 These tumors share morphologic features with BCOR-ITD SBRCTs, including monomorphic cells with delicate chromatin and indistinct nucleoli, areas of spindling, and rich capillary network.6 Moreover, our previous study showed an overlapping gene signature between these different SBRCT subsets harboring BCOR gene abnormalities. Specifically, we noted significant up-regulation of BCOR and SATB2 mRNA expression in round cell sarcomas with BCOR alterations (ITD, BCOR-CCNB3, BCOR-MAML3) and YWHAE-NUTM2B fusion, as well as in CCSKs.6 As the molecular investigation of each of this subset requires individual custom BAC probes for FISH or primer design for PCR assays, which are not widely available for routine diagnostic use, we assessed the specificity and sensitivity of BCOR and SATB2 antibodies for immunohistochemistry in this setting. Our results showed that the overwhelming majority of SBRCTs harboring BCOR-ITD, BCOR-CCNB3, BCOR-MAML3, and YWHAE-NUTM2B abnormalities demonstrate strong and diffuse nuclear immunoreactivity to BCOR. Our study also revealed strong BCOR immunostaining in CCSKs harboring BCOR ITD, YWHAE-NUTM2B fusion, or wild-type CCSKs.

In addition to BCOR, round cell sarcomas with BCOR-CCNB3 fusion were also shown to have CCNB3 mRNA up-regulation. As a consequence, CCNB3 overexpression by immunohistochemistry was demonstrated to be a useful ancillary marker in this subset.4 No CCNB3 mRNA up-regulation was identified in round cell sarcomas with BCOR ITD, BCOR-MAML3, or YWHAE-NUTM2B, by RNA sequencing and microarray data, respectively (data not shown); thus CCNB3 protein is most likely not overexpressed in these tumors.

Intriguingly, 2 of our undifferentiated round cell sarcomas without known gene fusions showed diffuse and strong BCOR positivity. The presence of BCOR and YWHAE rearrangements were excluded by FISH, and BCOR ITD was excluded by PCR in one of them which occurred in an infant. This finding indicated the existence of alternative genetic events in soft tissue round cell sarcomas that can drive the tumorigenesis with high BCOR expression.

As SBRCTs with BCOR genetic abnormalities can show focal areas of spindling, the differential diagnosis often includes a poorly differentiated or monophasic synovial sarcoma. Thus our investigation of BCOR immunoreactivity included a large number of synovial sarcomas, spanning all histologic subtypes and fusion transcripts. Somewhat unexpectedly, our results revealed that half of synovial sarcomas had variable degree of BCOR immunoreactivity. In contrast to the diffuse and strong staining pattern seen in SBRCTs with BCOR-gene alterations, BCOR immunoreactivity in synovial sarcomas was more variable in intensity and extent. There was no correlation between the BCOR staining pattern and histologic subtype or transcript variant of synovial sarcomas. Although all 3 poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas examined in whole sections showed diffuse and strong BCOR staining, further studies with larger case numbers are needed to determine whether the frequency of BCOR expression in poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas is different from monophasic and biphasic variants. At gene expression level, there was no significant difference in BCOR mRNA among the 3 different histologic subtypes of synovial sarcomas. It is intriguing to speculate that the histologic overlap with mixed round and spindle cell phenotype and BCOR immunoreactivity seen in both synovial sarcoma and SBRCT with BCOR-gene alterations might be related to the BCOR gene upregulation through different pathogenetic mechanisms.

In translocation-related mesenchymal tumors, BCOR gene has been involved both as 5’ (BCOR-CCNB3 and BCOR-MAML3 in SBRCT) and 3’ partners (ZC3H7B-BCOR in endometrial stromal sarcoma, ossifying fibromyxoid tumor and SBRCT).5,20,21 Our results showed that only tumors harboring fusions with 5’BCOR partner had BCOR protein overexpression by immunohistochemistry, while tumors with 3’BCOR fusions did not. All 3 tumors harboring ZC3H7B-BCOR fusion (2 endometrial stromal sarcomas and 1 ossifying fibromyxoid tumor) were negative for BCOR immunostaining. One explanation is that the BCOR monoclonal antibody sc-514576(c-10) used is against the first 300 amino acids of BCOR protein, which is not represented in the chimeric protein of ZC3H7B-BCOR. Furthermore, in contrast to the BCOR-CCNB3 or BCOR-MAML3 positive SBRCTs, our RNA sequencing data showed that tumors with ZC3H7B-BCOR fusion had low levels of BCOR mRNA expression.

Our study also attempted to establish the relevance of BCOR protein expression in the context of round cell sarcomas/SBRCT, as well as in the broader spectrum of different sarcoma types. In contrast to the diffuse and consistent staining results in SBRCTs with BCOR-gene abnormalities, BCOR reactivity was present with patchy moderate intensity only in one of the 8 Ewing sarcoma tested. Similarly, only 2/29 rhabdomyosarcomas and 1/6 round cell sarcomas with CIC rearrangements showed BCOR immunoreactivity with moderate intensity. Our results suggest that BCOR immunostaining can be used as a reliable marker in the differential diagnosis of various molecular subsets of SBRCTs, triage for further molecular studies if needed and avoid extensive immunohistochemical and molecular work-ups, especially in limited specimens. Aside from SBRCTs, BCOR expression was not found in other sarcomas examined, including angiosarcomas, chondrosarcomas, low grade fibromyxoid sarcomas, endometrial stroma sarcomas, and ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with ZC3H7B-BCOR, except for one myxofibrosarcoma (1%) showing moderate staining.

In search of possible mechanisms of BCOR up-regulation, we identified 4 differentially expressed TFs (GTF2I, MYC, MSX2, and GATA6) in synovial sarcomas that have binding motifs to the promoter region of BCOR. However, whether these TFs are involved in BCOR up-regulation requires further experimental work. In contrast, SBRCTs with BCOR ITD showed 19 differentially expressed TFs with motif sequences potentially binding to the BCOR promoter; however, none overlapped with the TFs found in synovial sarcoma. Other mechanisms of BCOR overexpression may involve epigenetic regulations. The SS18-SSX fusion transcript in synovial sarcoma is involved in chromatin modification through interaction with polycomb and SWI/SNF complexes.22,23 For BCOR ITD tumors, the duplicated BCOR sequences reside in the region encoding the PUFD (PCGF ubiquitin-like fold discriminator) domain of BCOR, which is responsible for the binding with PCGF1 (polycomb group ring finger 1) and the formation of a variant PRC1, involved in histone modification.6,18,24,25

Another marker evaluated in this study, SATB2 (special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2), is known as an osteoblastic as well as colorectal or appendiceal differentiation marker.26-28 SATB2 encodes a DNA-binding protein that also interacts with chromatin remodeling molecules, such as histone deacetylase 1 and metastasis-associated protein 2.29 Overall, SATB2 was positive in the majority (11/14; 79%) of round cell sarcomas with BCOR anomaly or YWHAE fusion. However, a greater degree of intratumoral heterogeneity with variations in the extent and intensity of staining was observed. Hence, SATB2 stain should be used with caution, especially in limited biopsy specimens. Of note, among the SATB2-positive round cell sarcomas, BCOR-CCNB3 tumors often arise as bone tumors in adolescent patients.4 SATB2 immunoreactivity, when interpreted as an osteoblastic marker, could lead to the misdiagnosis of a small cell osteosarcoma, as seen in one of our cases. Unlike BCOR stain, SATB2 expression was only seen in two out of six CCSKs tested. However, the gene expression data of CCSK revealed up-regulated SATB2 expression in the majority of cases irrespective of the genotype being BCOR ITD or YWHAE fusion. This result may reflect the greater variability of SATB2 protein expression identified by immunohistochemistry. Synovial sarcoma infrequently showed SATB2 immunoreactivity, which correlated to the low levels of SATB2 mRNA expression.

In conclusion, we demonstrated BCOR immunohistochemistry as a highly sensitive marker in identifying round cell sarcomas with BCOR abnormality, namely BCOR gene rearrangement or ITD, and YWHAE fusion. CCSK shares with these soft tissue tumors not only the histomorphology, genetic changes, but also BCOR immunoreactivity. Synovial sarcoma should also be included in the differential diagnosis in round cell sarcomas positive for BCOR stain. SATB2 immunoreactivity is also expressed in the majority of these tumors, although with lower sensitivity and greater variation of staining.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. BCOR staining in Ewing sarcoma and CIC-rearranged SBRCTs. Ewing sarcomas showed negative (A) or scattered rare staining (B), except for a single case with patchy moderate BCOR expression (C). CIC rearranged SBRCTs demonstrated similar results (D-F).

Supplementary Figure 2. A subset of SBRCTs lacking known fusion/ITD showed BCOR immunoreactivity. An orbital mass from a 1 year-old female composed of sheets of monomorphic round cells in a richly vascular background (A) showed diffuse and strong BCOR nuclear expression (B). A second case of a retroperitoneal mass in a 16 year-old male composed of a round cell sarcoma with focal spindling (C) and strong BCOR expression (D).

Supplementary Figure 3. Differentially expressed transcription factors with potential motifs binding to the BCOR promoter. (Upper left) Representative differentially expressed TFs in BCOR ITD tumors, ELF2, HES7, MXI1, EBF2, PITX1, ETV5, YWHAZ, INSM1, and SOX9, with sequence motifs binding to BCOR promoter (full list available in the Supplementary Table 1). HES7 and INSM1 are transcriptional repressors. ELF2 functions as a transcriptional activator and is significantly up-regulated in BCOR ITD tumors but not in other SBRCTs or other sarcomas (lower left) by RNA sequencing.6 (Upper right) GTF21, MYC, GATA6, and MSX2 are TFs up-regulated in synovial sarcomas with potential motifs on BCOR promoter. GATA6 up-regulation was present mainly in biphasic and monophasic synovial sarcomas and BCOR-CCNB3 tumors, compared to Ewing sarcoma on Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Plus 2 platform (lower right).4,13-15 Thickness of the arrows indicates the frequency of motif occurrence on BCOR promoter. Color represents the level of expression of each gene (red> orange>yellow).

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by: P50 CA140146-01 (CRA); P30-CA008748 (CRA); Kristen Ann Carr Foundation (CRA); Cycle for survival (CRA).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Italiano A, Sung YS, Zhang L, et al. High prevalence of CIC fusion with double-homeobox (DUX4) transcription factors in EWSR1-negative undifferentiated small blue round cell sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:207–218. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham C, Chilton-MacNeill S, Zielenska M, et al. The CIC-DUX4 fusion transcript is present in a subgroup of pediatric primitive round cell sarcomas. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugita S, Arai Y, Tonooka A, et al. A novel CIC-FOXO4 gene fusion in undifferentiated small round cell sarcoma: a genetically distinct variant of Ewing-like sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1571–1576. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierron G, Tirode F, Lucchesi C, et al. A new subtype of bone sarcoma defined by BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion. Nat Genet. 2012;44:461–466. doi: 10.1038/ng.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Specht K, Zhang L, Sung YS, et al. Novel BCOR-MAML3 and ZC3H7B-BCOR Gene Fusions in Undifferentiated Small Blue Round Cell Sarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016 doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, et al. Recurrent BCOR Internal Tandem Duplication and YWHAE-NUTM2B Fusions in Soft Tissue Undifferentiated Round Cell Sarcoma of Infancy: Overlapping Genetic Features With Clear Cell Sarcoma of Kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016 doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Specht K, Sung YS, Zhang L, et al. Distinct transcriptional signature and immunoprofile of CIC-DUX4 fusion-positive round cell tumors compared to EWSR1-rearranged Ewing sarcomas: further evidence toward distinct pathologic entities. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:622–633. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters TL, Kumar V, Polikepahad S, et al. BCOR-CCNB3 fusions are frequent in undifferentiated sarcomas of male children. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:575–586. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puls F, Niblett A, Marland G, et al. BCOR-CCNB3 (Ewing-like) sarcoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 10 cases, in comparison with conventional Ewing sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1307–1318. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueno-Yokohata H, Okita H, Nakasato K, et al. Consistent in-frame internal tandem duplications of BCOR characterize clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Nat Genet. 2015;47:861–863. doi: 10.1038/ng.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy A, Kumar V, Zorman B, et al. Recurrent internal tandem duplications of BCOR in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8891. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frosina D, Jungbluth AA. A Novel Technique for the Generation of Multitissue Blocks Using a Carrier. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama R, Mitani S, Nakagawa T, et al. Gene expression profiling of synovial sarcoma: distinct signature of poorly differentiated type. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1599–1607. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f7ce2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pei H, Li L, Fridley BL, et al. FKBP51 affects cancer cell response to chemotherapy by negatively regulating Akt. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griesinger AM, Birks DK, Donson AM, et al. Characterization of distinct immunophenotypes across pediatric brain tumor types. J Immunol. 2013;191:4880–4888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson J, Holmquist Mengelbier L, Ciornei CD, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney demonstrates an embryonic signature indicative of a primitive nephrogenic origin. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:381–391. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huynh KD, Fischle W, Verdin E, et al. BCoR, a novel corepressor involved in BCL-6 repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1810–1823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gearhart MD, Corcoran CM, Wamstad JA, et al. Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6880–6889. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00630-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argani P, Perlman EJ, Breslow NE, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: a review of 351 cases from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group Pathology Center. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:4–18. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panagopoulos I, Thorsen J, Gorunova L, et al. Fusion of the ZC3H7B and BCOR genes in endometrial stromal sarcomas carrying an X;22-translocation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:610–618. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonescu CR, Sung YS, Chen CL, et al. Novel ZC3H7B-BCOR, MEAF6-PHF1, and EPC1-PHF1 fusions in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors--molecular characterization shows genetic overlap with endometrial stromal sarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:183–193. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia CB, Shaffer CM, Eid JE. Genome-wide recruitment to Polycomb-modified chromatin and activity regulation of the synovial sarcoma oncogene SYT-SSX2. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato H, Tjernberg A, Zhang W, et al. SYT associates with human SNF/SWI complexes and the C-terminal region of its fusion partner SSX1 targets histones. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5498–5505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Z, Zhang J, Bonasio R, et al. PCGF homologs, CBX proteins, and RYBP define functionally distinct PRC1 family complexes. Mol Cell. 2012;45:344–356. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Junco SE, Wang R, Gaipa JC, et al. Structure of the polycomb group protein PCGF1 in complex with BCOR reveals basis for binding selectivity of PCGF homologs. Structure. 2013;21:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conner JR, Hornick JL. SATB2 is a novel marker of osteoblastic differentiation in bone and soft tissue tumours. Histopathology. 2013;63:36–49. doi: 10.1111/his.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dragomir A, de Wit M, Johansson C, et al. The role of SATB2 as a diagnostic marker for tumors of colorectal origin: Results of a pathology-based clinical prospective study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141:630–638. doi: 10.1309/AJCPWW2URZ9JKQJU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strickland S, Parra-Herran C. Immunohistochemical characterization of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms and the value of special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 in their distinction from primary ovarian mucinous tumours. Histopathology. 2016;68:977–987. doi: 10.1111/his.12899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gyorgy AB, Szemes M, de Juan Romero C, et al. SATB2 interacts with chromatin-remodeling molecules in differentiating cortical neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:865–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. BCOR staining in Ewing sarcoma and CIC-rearranged SBRCTs. Ewing sarcomas showed negative (A) or scattered rare staining (B), except for a single case with patchy moderate BCOR expression (C). CIC rearranged SBRCTs demonstrated similar results (D-F).

Supplementary Figure 2. A subset of SBRCTs lacking known fusion/ITD showed BCOR immunoreactivity. An orbital mass from a 1 year-old female composed of sheets of monomorphic round cells in a richly vascular background (A) showed diffuse and strong BCOR nuclear expression (B). A second case of a retroperitoneal mass in a 16 year-old male composed of a round cell sarcoma with focal spindling (C) and strong BCOR expression (D).

Supplementary Figure 3. Differentially expressed transcription factors with potential motifs binding to the BCOR promoter. (Upper left) Representative differentially expressed TFs in BCOR ITD tumors, ELF2, HES7, MXI1, EBF2, PITX1, ETV5, YWHAZ, INSM1, and SOX9, with sequence motifs binding to BCOR promoter (full list available in the Supplementary Table 1). HES7 and INSM1 are transcriptional repressors. ELF2 functions as a transcriptional activator and is significantly up-regulated in BCOR ITD tumors but not in other SBRCTs or other sarcomas (lower left) by RNA sequencing.6 (Upper right) GTF21, MYC, GATA6, and MSX2 are TFs up-regulated in synovial sarcomas with potential motifs on BCOR promoter. GATA6 up-regulation was present mainly in biphasic and monophasic synovial sarcomas and BCOR-CCNB3 tumors, compared to Ewing sarcoma on Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Plus 2 platform (lower right).4,13-15 Thickness of the arrows indicates the frequency of motif occurrence on BCOR promoter. Color represents the level of expression of each gene (red> orange>yellow).