Abstract

Objective

Although a high incidence of chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) following traumatic subdural hygroma (SDG) has been reported, no study has evaluated risk factors for the development of CSDH. Therefore, we analyzed the risk factors contributing to formation of CSDH in patients with traumatic SDG.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed patients admitted to Hallym University Hospital with traumatic head injury from January 2004 through December 2013. A total of 45 patients with these injuries in which traumatic SDG developed during the follow-up period were analyzed. All patients were divided into two groups based on the development of CSDH, and the associations between the development of CSDH and independent variables were investigated.

Results

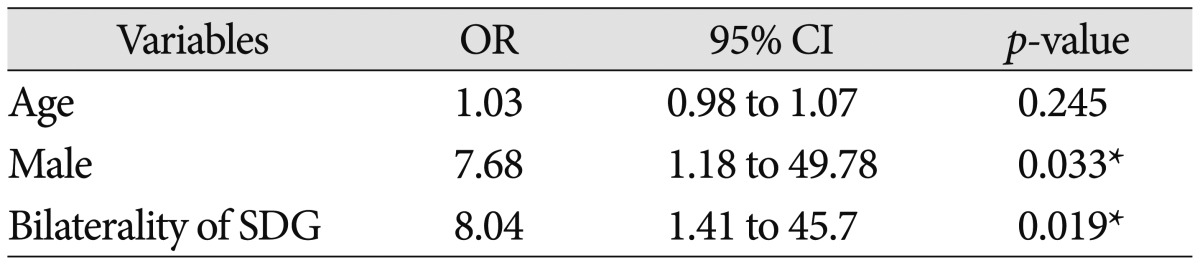

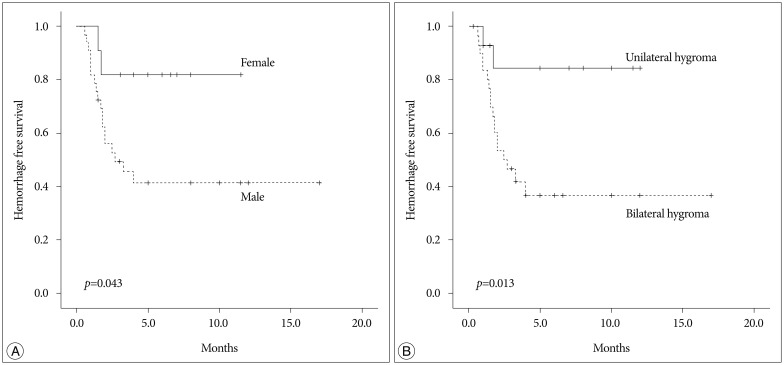

Thirty-one patients suffered from bilateral SDG, whereas 14 had unilateral SDG. Follow-up computed tomography scans revealed regression of SDG in 25 of 45 patients (55.6%), but the remaining 20 patients (44.4%) suffered from transition to CSDH. Eight patients developed bilateral CSDH, and 12 patients developed unilateral CSDH. Hemorrhage-free survival rates were significantly lower in the male and bilateral SDG group (log-rank test; p=0.043 and p=0.013, respectively). Binary logistic regression analysis revealed male (OR, 7.68; 95% CI 1.18–49.78; p=0.033) and bilateral SDG (OR, 8.04; 95% CI 1.41–45.7; p=0.019) were significant risk factors for development of CSDH.

Conclusion

The potential to evolve into CSDH should be considered in patients with traumatic SDG, particularly male patients with bilateral SDG.

Keywords: Chronic subdural hematoma, Subdural hygroma

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic subdural hygroma (SDG) is an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subdural space that develops in 4–6% of patients with a head injury17). Most SDGs are asymptomatic with little mass effect, and do not require surgical intervention at the time of diagnosis. However, studies have reported the subsequent formation of chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) following traumatic SDG5,7,12,16,17,19,22,27). Since Yamada et al.27) first reported three cases of traumatic SDG complicated by CSDH in 1979, several studies have reported CSDH rates of 4–58% following traumatic SDG5,7,12,17,19).

Despite the considerable rate of transition to CSDH in patients with traumatic SDG, the pathomechanism remains unclear. Furthermore, no study has investigated the risk factors for developing CSDH following traumatic SDG. In the present study, we explored the risk factors that contribute to formation of CSDH in patients with traumatic SDG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 2950 patients were admitted to Hallym University Hospital for traumatic head injury between January 2004 and December 2013. Among them, we identified 89 patients by searching the final imaging analysis program reports (PiViewSTAR, INFINITT, Seoul, Korea) with keywords including 'subdural hygroma' or 'subdural fluid collection' which developed within 3 months after trauma. Of these, patients with a hemostatic disorder (n=5), acute subdural hemorrhage (n=10), external hydrocephalus; defined as enlargement of subarachnoid or subdural space in the presence of ventriculomegaly or increased intracranial pressure (n=5), and SDG related to craniotomy, infection, and other brain pathology (n=15) were excluded. To avoid confusion for the differential diagnosis of atrophic brain with a widened CSF space, SDG found at the time of initial brain imaging on admission was also excluded (n=9). Finally, we identified 45 patients with traumatic head injury in which traumatic SDG developed during the follow-up period.

The diagnosis of traumatic SDG was based on radiological findings showing homogenous subdural fluid collection with low computed tomography (CT) density similar to that seen in CSF after trauma. Regular follow-up CT was performed every week or at the onset of symptom exacerbation. If newly developed SDG was found on follow-up CT, we recommended further evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Pachymeningeal enhancement was defined as linear enhancement of dura mater on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted or Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging. We performed surgical drainage using a relatively consistent methodology in symptomatic patients with newly developed CSDH. Surgical procedures consisted of a single burr hole followed by inserting a drainage catheter.

Initial mental status was evaluated by Glasgow Coma Score (GCS), and the last functional outcome was assessed by the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS). All patients were divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of CSDH. We investigated the associations between CSDH development and independent variables, including demographic factors and radiological findings. The chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous data. All statistical tests were performed using the two-tailed methods. Independent variables with p-values<0.20 were included in binary logistic regression analysis to determine the factors affecting CSDH development. The correlation between significant factors and hemorrhage-free survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done using IBM SPSS software ver. 22.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

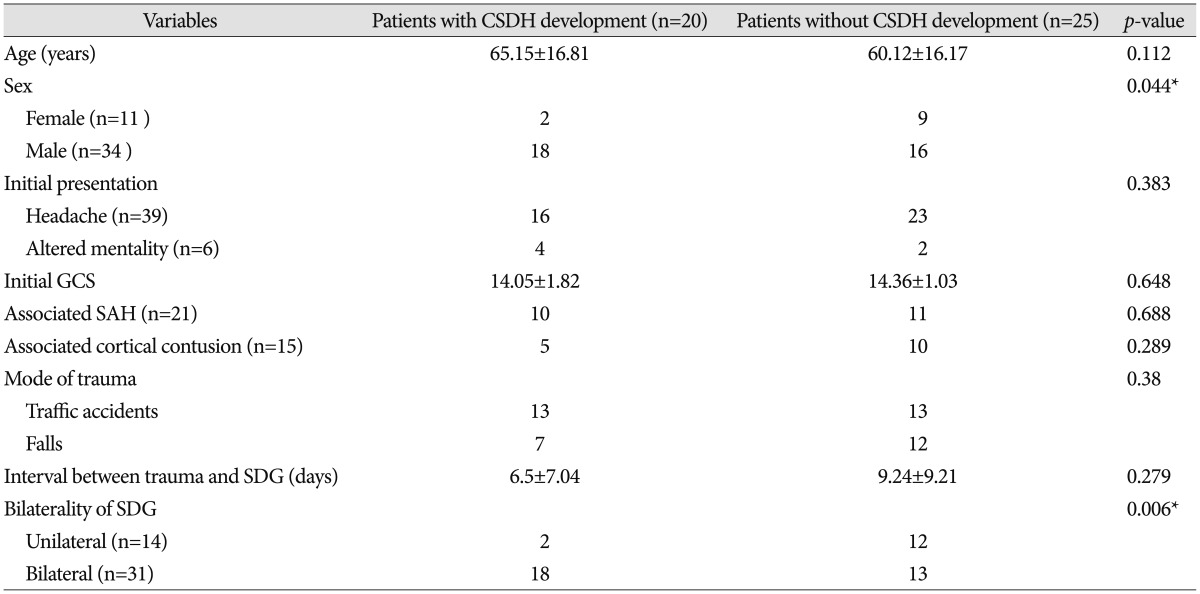

Table 1 shows the results of the risk factor analysis for the development of CSDH. Mean patient age was 62.36±16.47 years (range, 10–84 years). The female to male ratio was 1 : 3.1. The most common clinical manifestations were headache (86.7%), followed by altered mental status after trauma (13.3%). Traffic accidents (50%) and falls (50%) were the main causes of head trauma. The mean GCS score at admission was 14.22±1.43 (range, 8–15), and 39 of 45 patients (86.7%) scored ≥14. The most common associated injury was traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage in 21 patients (46.7%), followed by cortical contusion in 15 patients (33.3%). The mean follow-up period was 143.1±130.8 days (range, 10–510 days). The mean GOS score at the time of the last follow-up visit was 4.82±0.44 (range, 3–5).

Table 1. Analysis of risk factors for the development of chronic subdural hematoma.

*p<0.05 is significant. CSDH : chronic subdural hematoma, GCS : glasgow coma scale, SAH : subarachnoid hemorrhage, SDG : subdural hygroma

Transition from traumatic subdural hygroma to chronic subdural hematoma

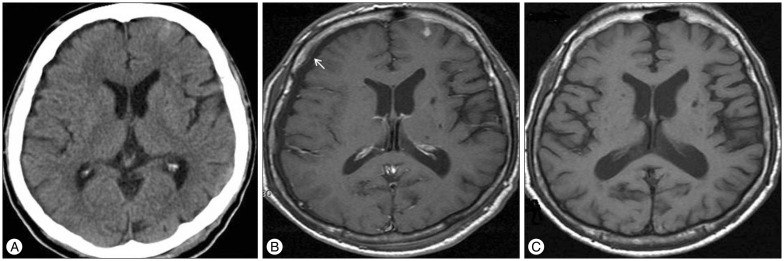

The mean time for development of SDG from trauma was 8.02±8.35 days (range, 1–40 days). Thirty-one patients suffered from bilateral SDG, and the remaining 14 patients had unilateral SDG. Regular follow-up CT scans were performed in all patients, including those with newly developed clinical deterioration. Follow-up CT scans revealed regression of SDG in 25 of 45 patients (55.6%), including 13 patients with bilateral SDG and 12 patients with unilateral SDG (Fig. 1). The mean time for SDG regression was 112.1 days (range, 10–365 days).

Fig. 1. Initial CT scan of 63 years old male shows hemorrhagic contusion at the left frontal and temporal lobe (arrow) (A). Follow-up contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI reveals newly developed subdural hygroma (arrow) at the right frontal lobe with minimal enhancement of pachymeninx (B) after 4 days from trauma. Follow-up MRI after 10 days from trauma showed regression of subdural hygroma (C). CT : computed tomography, MRI : magnetic resonance imaging.

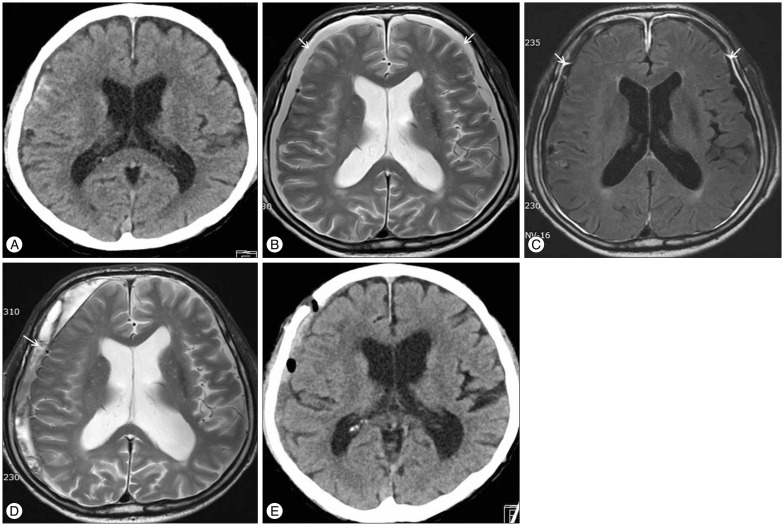

The remaining 20 patients (44.4%) showed transition to CSDH during the follow-up period (Fig. 2). The mean time from SDG to development of CSDH was 48.35±23.8 days (range, 17–120 days). Eight patients developed bilateral CSDH, and 12 patients developed unilateral CSDH. The most common clinical manifestations were headache (9 of 20), followed by hemiparesis (6 of 20), and drowsiness (2 of 20). Three asymptomatic patients were treated conservatively due to the small amount of CSDH. The remaining 17 patients with symptomatic CSDH underwent surgical drainage. Final CT scans after surgery revealed complete regression of CSDH in 15 of 17 patients. Recurrence of CSDH occurred in two patients on the same side and they underwent a re-operation later.

Fig. 2. Initial CT scan of 70 years old male shows traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage at the right frontal lobe (A). Follow-up T2-weighted MRI demonstrated newly developed subdural hygroma (arrow) at the both frontal lobe (B), and strong enhancement of pachymeninx (arrow) (C) on contrast-enhanced fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging after 2 days from trauma. Subdural hygroma developed into chronic subdural hematoma (arrow) at the right hemisphere after 3 month (D). The amount of subdural hematoma decheased after surgical drainage (E). CT : computed tomography, MRI : magnetic resonance imaging.

Risk factor analysis for the development of chronic subdural hematoma

The clinical and radiological risk factors for the development of CSDH are presented in Table 1. The mean age of patients with CSDH development tended to be older than those without CSDH development (65.15 vs. 60.12 years, p=0.112). Female and male patients showed significantly different transition rates to CSDH (22.2% vs. 52.9%, p=0.044). However, the clinical presentation and initial GCS were not different between the two groups. Neither associated traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage nor cortical contusion was related with the development of CSDH. Interval from trauma to SDG was not significantly different between patients with CSDH development and patients without CSDH development (6.5 vs. 9.24 days, p=0.279). Patients with bilateral SDG transitioned to the CSDH more frequently than those with unilateral SDG (58.1% vs. 14.3%, p=0.006). The multivariate analysis revealed that male (OR, 7.68; 95% CI 1.18–49.78; p=0.033) and bilateral SDG (OR, 8.04; 95% CI 1.41–45.7; p=0.019) were significant risk factors for development of CSDH (Table 2). Hemorrhage-free survival rates were significantly lower in the male and bilateral SDG group (log-rank test; p=0.043 and p=0.013, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of factors affecting the development of chronic subdural hematoma.

*p<0.05 is significant. SDG : subdural hygroma

Fig. 3. Kaplan Meier survival analysis according to gender (A) and bilaterality (B) of subdural hygroma.

Magnetic resonance imaging findings in patients with subdural hygroma

Among the 45 patients with newly developed SDG, 15 (33%) were evaluated with MRI. Of them, nine patients (60%) showed diffuse symmetric pachymeningeal enhancement (Fig. 2), and the remaining six (40%) did not (Fig. 1). Of the nine patients with pachymeningeal enhancement on contrast-enhanced MRI, seven (78%) developed CSDH during the follow-up period. CSDH did not develop in the six patients who did not show pachymeningeal enhancement on MRI.

DISCUSSION

Many studies have described the development of SDG after traumatic brain injury and the transition to CSDH. However, no study has investigated risk factors for the development of CSDH following traumatic SDG. This is the first study to perform a statistical analysis to elucidate the risk factors associated with transition to CSDH.

Several mechanisms have been suggested with regard to the development of SDG after traumatic brain injury. Traumatic separation of the dura-arachnoid interface at the dural border cell layer, and effusion from traumatized vessels can lead to fluid collection18,25). An arachnoid tear and CSF influx into the subdural space through a flap valve mechanism has also been proposed3,4,10).

The possible explanation for the fate of traumatic SDG whether it regresses or evolves into CSDH is unclear. Some authors have suggested that premorbid conditions, such as cerebral atrophy, which is more common in older patients, may contribute to the development of CSDH9,12,14). Our results are contrary with this hypothesis. Although patients with CSDH tended to be older than those without CSDH, the difference was not significant. Because we excluded patients who had a collection of subdural fluid at the time of initial brain imaging and only included patients with newly developed SDG, we avoided the difficulty distinguishing between traumatic SDG and premorbid cerebral atrophy.

Delayed resorption of the SDG and tearing of the elongated bridging veins results in hemorrhage into the subdural space. A neomembrane forms if SDG with a bleeding component persists 1,13,26). Bleeding in the SDG induces migration or proliferation of inflammatory cells derived from dural border cells, resulting in a layer of fibroblasts along the dura, which develops into the outer membrane of the hematoma6,11,15,21). Hasegawa et al.8) reported meningeal enhancement on MRI with Gd-DTPA (gadolinium diethylene-triamine-pentaacetic acid) enhancement in five patients with traumatic SDG. In that study, a microscopic examination of the enhanced dura mater revealed a vascularized neomembrane in which the vessel endothelium showed numerous pinocytic vesicles and fenestrations, suggesting that SDG with meningeal enhancement has potential to develop into CSDH. Although the number of patients evaluated by MRI was too small to show statistical significance, the results of our study also support this hypothesis, as seven of nine patients with pachymeningeal enhancement developed CSDH.

Previous studies have shown a marked male preponderance for the development of SDG, as well as transition to CSDH2,20,23,24). This tendency can also be seen in our study. One rationale for male dominance is that men generally have greater exposure to injuries. Although the significance of bilateral SDG for the development of CSDH has not been described, our results show that bilateral SDG was a significant risk factor for the development of CSDH. More severe injuries may have resulted in bilateral rather than unilateral SDG. Furthermore, persistent bilateral fluid collection could have disturbed expansion of the brain parenchyma and facilitated formation of CSDH than that of unilateral SDG.

The limitations of this study should be considered. First, the diagnosis of SDG and CSDH was confirmed by radiology report based on visual assessment rather than objective measurement with parameters such as Hounsfield units. Second, this retrospective study was conducted in a single institute with relatively a small number of cases. Further prospective studies are needed to ascertain the role of sex differences and bilateral SDG for the development of CSDH.

CONCLUSION

CSDHs are common neurosurgical problems associated with significant morbidity in patients with traumatic brain injury. The potential to evolve into CSDH should be considered in patients with traumatic SDG, particularly male patients with bilateral SDG. Further studies are necessary to elucidate whether pachymeningeal enhancement on MRI is a prognostic factor for the development of CSDH in patients with SDG.

References

- 1.Apfelbaum RI, Guthkelch AN, Shulman K. Experimental production of subdural hematomas. J Neurosurg. 1974;40:336–346. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.40.3.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baechli H, Nordmann A, Bucher HC, Gratzl O. Demographics and prevalent risk factors of chronic subdural haematoma : results of a large single-center cohort study. Neurosurg Rev. 2004;27:263–266. doi: 10.1007/s10143-004-0337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldarelli M, Di Rocco C, Romani R. Surgical treatment of chronic subdural hygromas in infants and children. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:581–588. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-0947-0. discussion 588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dandy WE. Treatment of an unusual subdural hydroma (external hydrocephalus) Arch Surg. 1946;52:421–428. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1946.01230050428003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.French BN, Cobb CA, 3rd, Corkill G, Youmans JR. Delayed evolution of posttraumatic subdural hygroma. Surg Neurol. 1978;9:145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friede RL, Schachenmayr W. The origin ofsubdural neomembranes. II. Fine structural of neomembranes. Am J Pathol. 1978;92:69–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujioka S, Matsukado Y, Kaku M, Sakurama N, Nonaka N, Miura G. [CT analysis of 100 cases with chronic subdural hematoma with respect to clinical manifestation and the enlarging process of the hematoma (author's transl)] Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1981;21:1153–1160. doi: 10.2176/nmc.21.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasegawa M, Yamashima T, Yamashita J, Suzuki M, Shimada S. Traumatic subdural hygroma : pathology and meningeal enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:580–585. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199209000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufman HH, Childs TL, Wagner KA, Bernstein DP, Karon M, Khalid M, et al. Post-traumatic subdural hygromas : observations concerning a surgical enigma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1984;72:197–209. doi: 10.1007/BF01406870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawaguchi T, Fujita S, Hosoda K, Shibata Y, Komatsu H, Tamaki N. Treatment of subdural effusion with hydrocephalus after ruptured intracranial aneurysm clipping. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1033–1039. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199811000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawano N, Endo M, Saito M, Yada K. [Origin of the capsule of a chronic subdural hematoma--an electron microscopy study] No Shinkei Geka. 1988;16:747–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KS, Bae WK, Bae HG, Yun IG. The fate of traumatic subdural hygroma in serial computed tomographic scans. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:560–568. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.5.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee KS, Bae WK, Park YT, Yun IG. The pathogenesis and fate of traumatic subdural hygroma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:551–558. doi: 10.3109/02688699409002947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KS, Bae WK, Yoon SM, Doh JW, Bae HG, Yun IG. Location of the traumatic subdural hygroma : role of gravity and cranial morphology. Brain Inj. 2000;14:355–361. doi: 10.1080/026990500120646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakaguchi H, Tanishima T, Yoshimasu N. Factors in the natural history of chronic subdural hematomas that influence their postoperative recurrence. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:256–262. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.2.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohno K, Suzuki R, Masaoka H, Matsushima Y, Inaba Y, Monma S. Role of traumatic subdural fluid collection in developing process of chronic subdural hematoma. Bull Tokyo Med Dent Univ. 1986;33:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohno K, Suzuki R, Masaoka H, Matsushima Y, Inaba Y, Monma S. Chronic subdural haematoma preceded by persistent traumatic subdural fluid collection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:1694–1697. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.12.1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park CK, Choi KH, Kim MC, Kang JK, Choi CR. Spontaneous evolution of posttraumatic subdural hygroma into chronic subdural haematoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994;127:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01808545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SH, Lee SH, Park J, Hwang JH, Hwang SK, Hamm IS. Chronic subdural hematoma preceded by traumatic subdural hygroma. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:868–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambasivan M. An overview of chronic subdural hematoma : experience with 2300 cases. Surg Neurol. 1997;47:418–422. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schachenmayr W, Friede RL. The origin of subdural neomembranes. I. Fine structure of the dura-arachnoid interface in man. Am J Pathol. 1978;92:53–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohn IT, Lee KS, Doh JW, Bae HG, Yun IG, Byun BJ. A prospective study on the incidence, patterns and premorbid conditions of traumatic subdural hygroma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 1997;26:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sousa EB, Brandão LF, Tavares CB, Borges IB, Neto NG, Kessler IM. Epidemiological characteristics of 778 patients who underwent surgical drainage of chronic subdural hematomas in Brasília, Brazil. BMC Surg. 2013;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spallone A, Giuffrè R, Gagliardi FM, Vagnozzi R. Chronic subdural hematoma in extremely aged patients. Eur Neurol. 1989;29:18–22. doi: 10.1159/000116370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone JL, Lang RG, Sugar O, Moody RA. Traumatic subdural hygroma. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:542–550. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe S, Shimada H, Ishii S. Production of clinical form of chronic subdural hematoma in experimental animals. J Neurosurg. 1972;37:552–561. doi: 10.3171/jns.1972.37.5.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada H, Nihei H, Watanabe T, Shibui S, Murata S. [Chronic subdural hematoma occurring consequently to the posttraumatic subdural hygroma--on the pathogenesis of the chronic subdural hematoma (author's transl)] No To Shinkei. 1979;31:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]