Abstract

Background

Alzheimer disease (AD) and Parkinson disease (PD) involve tau pathology. Tau is detectable in blood, but its clearance from neuronal cells and the brain is poorly understood.

Methods

Tau efflux from the brain to the blood was evaluated by administering radioactively labeled and unlabeled tau intracerebroventricularly in wild-type and tau knock-out mice, respectively. Central nervous system (CNS)-derived tau in L1CAM-containing exosomes was further characterized extensively in human plasma, including by Single Molecule Array technology with 303 subjects.

Results

The efflux of Tau, including a fraction via CNS-derived L1CAM exosomes, was observed in mice. In human plasma, tau was explicitly identified within L1CAM exosomes. In contrast to AD patients, L1CAM exosomal tau was significantly higher in PD patients than controls, and correlated with cerebrospinal fluid tau.

Conclusions

Tau is readily transported from the brain to the blood. The mechanisms of CNS tau efflux are likely different between AD and PD.

Keywords: Central nervous system protein efflux, Central nervous system-derived exosomes, Tau, Blood plasma, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, Biomarkers

1. Introduction

Tau plays a critical role in tauopathies, especially Alzheimer disease (AD) [1]. It is a microtubule stabilizing protein, normally highly soluble and typically localized to neuronal axons, which under pathological conditions becomes hyperphosphorylated and prone to form the aggregate tangles that define tauopathies. A contemporary hypothesis in tauopathies involves the spread of toxic tau species from cell-to-cell via various mechanisms, including exosomes [2], which are 40–100 nm membrane vesicles of endocytic origin. Tau secretion via exosomes and other forms has also been proposed as a toxicity attenuation mechanism [3]. A recent study has suggested that exosomal tau in plasma is increased in AD patients compared to controls [4].

Notably, the latest evidence, including the association of tau gene (MAPT) with the risk of sporadic Parkinson disease (PD) [5, 6], has also implicated a role for tau in PD [5–7]. Intriguingly, no such genetic association has been observed in AD. How tau is transported and whether exosomal mechanisms are involved in PD are entirely unknown. In this study, we provide direct evidence showing that central nervous system (CNS) tau can be transported into peripheral blood, and that the mechanism(s) of tau transport in PD may be distinctly different from AD.

2. Methods

2.1 Brain-to-blood tau efflux in mice

An intracerebroventricular (icv) method [8, 9] was used in CD-1 male mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA), B6.129X1-Mapttm1Hnd/J tau knock-out (KO) mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and their wild-type controls (C57BL/6J, The Jackson Laboratory) to assess the brain-to-blood efflux of tau. Details on animal use, radioisotopic labeling, efflux kinetics studies, and in vivo stability of labeled tau can be found in Supplementary Methods.

2.2 Human subjects and clinical sample collection

A total of 303 subjects (91 patients with PD, 106 patients with AD, and 106 age- and sex-matched healthy controls) were included in this study (Table 1). The inclusion and exclusion criteria [10–13] and sample collection [12, 14] have been previously described (see also Supplementary Methods).

Table 1.

Demographics of participating subjects, and plasma and CSF protein concentrations in diagnostic groups

| Control | PD | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject number | 106 | 91 | 106 |

| Age* (range) |

67.1±7.4 (51–84) |

65.0±11.1 (32–84) |

69.5±8.1 (52–84) |

| Sex (male:female) | 1.2 (58:48) | 2.5 (65:26) | 1.2 (57:49) |

| UPDRS motor* (range) |

- | 26.3±13.8 (3–67) |

- |

| H&Y* (range) |

- | 2.2±0.7 (1–5) |

- |

| MMSE* (range) |

29.2±1.1 (28–30) |

27.6±3.0 (18–30) |

21.3±5.7 (4–27) |

| Disease duration, year* (range) |

- | 6.0±4.6 (0–21) |

4.5±2.8 (0–13) |

| L1CAM exosomal tau (pg/mL plasma)* (range) |

0.178±0.138 (0.010–0.835) |

0.260±0.452 (0.020–4.262) |

0.172±0.096 (0.003–0.584) |

| Plasma tau (pg/mL)* (range) |

2.405±2.759 (0.498–29.19) |

2.660±2.872 (0.504–25.87) |

3.780±2.221 (0.602–14.42) |

| CSF t-tau (pg/mL)* (range) |

56.1±25.6 (11.7–226.1) |

48.5±21.1 (18.8–136.2) |

109.3±68.0 (40.7–374.1) |

| CSF p-tau (pg/mL)* (range) |

35.4±13.9 (13.4–102.4) |

29.4±12.6 (13.2–86.3) |

72.8±46.9 (19.8–250.0) |

| CSF Aβ42 (pg/mL)* (range) |

327.2±153.2 (60.6–821.2) |

362.6±114.7 (104.5–637.6) |

216.8±128.5 (48.9–1021.0) |

Mean±SD.

AD, Alzheimer disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; H&Y, Hoehn & Yahr; L1CAM, L1 cell adhesion molecule; MMSE, Mini Mental State Exam; PD, Parkinson disease; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

2.3 Exosome isolation

Exosomes containing L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM), a putative CNS-specific marker, were isolated from mouse or human plasma following an immunocapture protocol published previously [9]. See Supplementary Methods for more details on isolation and mass spectrometry (MS) identification of tau in these exosomes.

2.4 Fluorescence nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

Tau KO mice were intracerebroventricularly injected with recombinant human tau protein 2N4R or saline as a negative control and L1CAM-containg exosomes were isolated from blood plasma using immunocapture. The exosomes, with or without permeabilization, were labeled with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-tau antibody (Tau-5) or mouse IgG isotype control and analyzed using a NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). More details can be found in Supplementary Methods.

2.5 Immunoassays

Exosomal and whole plasma tau were quantified using a human tau Simoa (Single Molecule Array) kit (Quanterix, Lexington, MA, USA) with a Simoa HD-1 analyzer (Quanterix), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CSF total tau (t-tau), phosphorylated tau at 181 (p-tau), and Aβ42 concentrations were measured using the INNO-BIA AlzBio3 kit obtained from Innogenetics/Fujirebio Europe (Ghent, Belgium) as previously described [12] (more details in Supplementary Methods).

2.6 Statistical analysis

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post-test was used to compare group means. Ability of analytes to distinguish disease and healthy subjects was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Correlation analysis and other details can be found in Supplementary Methods. Values with p<0.05 were regarded as significant.

3. Results

3.1 Transportation of tau from the brain to blood in mice

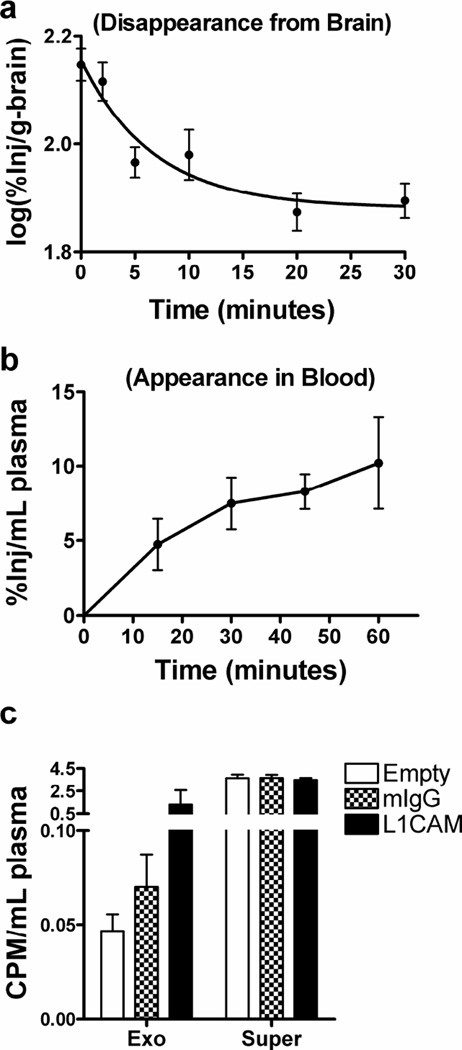

We icv-injected 125I-labeled tau 2N4R (I-Tau) into mouse brain, and observed a rapid initial clearance of I-Tau from the brain (half-time clearance of 4.86 min following a one phase decay model; Fig. 1a). This was accompanied by the appearance of acid-precipitable (i.e., protein-conjugated) radioactivity in plasma/serum (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a), indicating transportation of tau protein from the brain (CSF) into blood.

Fig. 1. Transportation of tau from the brain to blood.

(a–b) Mice were intracerebroventricularly injected with 125I-labeled tau 2N4R (I-Tau). Brain (a) and blood plasma (b) were then collected at indicated time points after injection. Levels of radioactivity in the samples were determined using a gamma counter. See also Supplementary Fig. 1a for the early phase efflux kinetics of I-Tau. (c) Blood was collected at 60 min after injection, followed by anti-L1CAM immunocapture of exosomes from platelet-free plasma. Normal mouse IgG-captured (mIgG) or “Empty” (no bead “capture”) samples were used as controls. Levels of radioactivity were measured in the whole brain, the whole plasma, the plasma L1CAM-containing exosome fraction (Exo), and the exosome-less fraction (supernatant after immunoaffinity capture; Super). Data shown are mean ± S.D. from 4–6 mice at each time point. CPM, counts per minute.

We further compared the clearance of I-Tau at later time points to that of co-injected 131I-labeled albumin (I-Alb), a protein cleared from brain by bulk flow [15]. Both the slower decrease of tau in brain (p<0.0001; Supplementary Fig. 1b) and higher appearance of albumin in blood (two way ANOVA p<0.01; Supplementary Fig. 1c) reflect significantly faster clearance of albumin from the brain than tau, suggesting sequestering of tau by brain (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for more details).

To determine if I-Tau could be transported in L1CAM-containing, likely CNS-derived, exosomes in plasma, similar to our recent finding using icv-injected 125I-labeled α-synuclein [9], we isolated such exosomes from mouse plasma collected 60 min after injection. I-tau was detected in the anti-L1CAM-captured exosome fraction, while the radioactivity from normal mouse IgG-captured or no bead “capture” samples was minimal (Fig. 1c). Notably, the majority of the radioactivity appeared to be in the exosome-depleted supernatants (Fig. 1c).

To further confirm that icv-injected tau proteins could be transported into blood via exosomes, we injected unlabeled human tau 2N4R protein into tau KO mouse brain and isolated L1CAM-containing exosomes from blood plasma. The exosomes, with or without permeabilization using 0.2% Tween-20, were labeled with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-tau antibody or mouse IgG isotype control and then analyzed using the NTA technology, which allows direct and individual visualization of specific exosomes and microvesicles in liquid suspension in real-time and provides size distribution profiles, concentration measurements and phenotyping of the particles [16]. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, the anti-L1CAM immunocapture isolated microvesicles mainly around the exosome size. Furthermore, tau positive fluorescent particles were detected in permeabilized L1CAM-containing exosome samples isolated from tau-injected, but not saline-injected, tau KO mouse plasma (Supplementary Fig. 2d), confirming the CNS tau efflux via exosomes. Interestingly, no tau positive particles were observed if the samples were not permeabilized (Supplementary Fig. 2b), suggesting that the exosome-associated tau was mainly inside the exosomes, but not on the surface.

3.2 Identification of tau in human plasma exosomes and immunoassay development

To further characterize L1CAM exosomal tau that may be practically captured and specifically measured in human samples, we performed proteomic analyses (general profiling and tau targeted) of anti-L1CAM-captured exosomes from pooled reference human plasma, and identified at least five peptides derived from tau in the L1CAM-containing exosome preparations, but not in normal IgG controls (Supplementary Fig. 3), further verifying the presence of tau in this likely CNS-derived source in human.

We found that in L1CAM-containing plasma exosomes, tau was largely undetectable using traditional ELISA or Luminex immunoassays, including the Innogenetics assays commonly used by us and others [12, 17]. This contrasted with another recent study [4], where contamination might be a problem (see Discussion). Therefore, we turned to a newly developed technology, Simoa [18], which makes use of arrays of femtoliter-sized reaction chambers to isolate and detect single protein molecules [18, 19]. A representative calibration curve of the Simoa tau assay is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Repeated testing of the new platform confirmed that the assay featured a limit of detection of ~0.02 pg/mL [20–22], accuracy of 91.5±7.9% (mean±S.D.) when measuring plasma exosomal samples, and accuracy of ≥70% when measuring whole plasma samples.

3.3 Evaluation of plasma exosomal tau in clinical samples

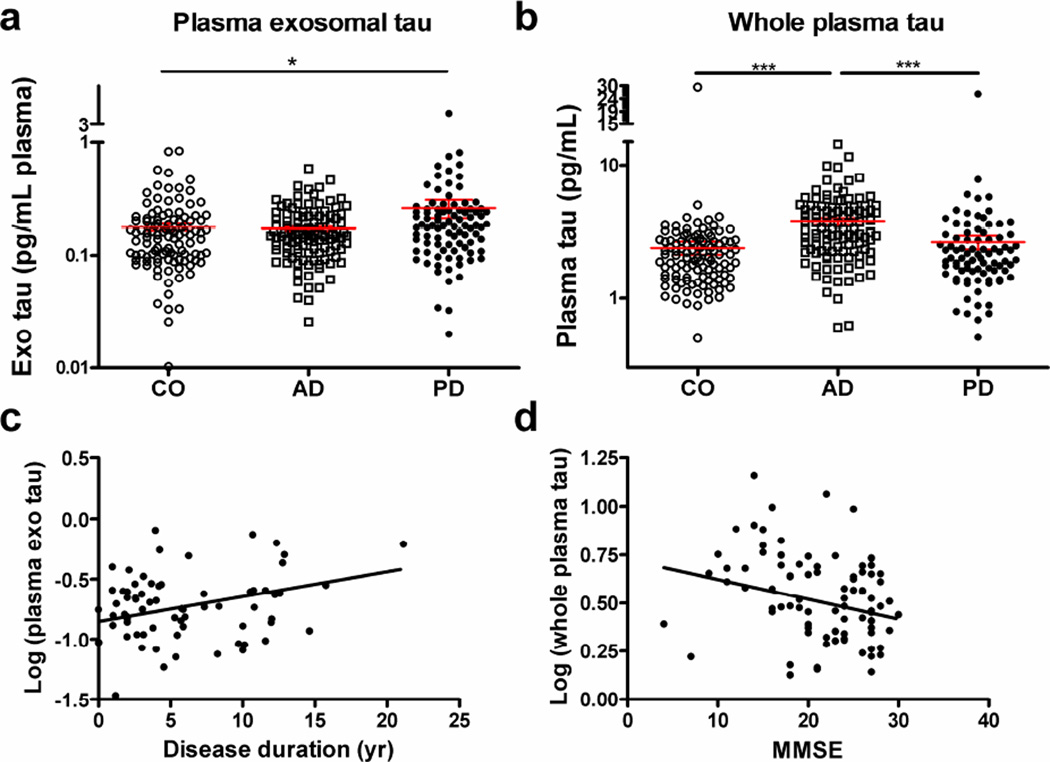

Using Simoa assays, we measured tau in whole plasma and L1CAM-containing plasma exosomes from a large cohort of 91 PD, 106 AD, and 106 healthy control subjects. Control subjects were frequency matched on age and sex to PD and AD subjects. Table 1 summarizes the data. Mean plasma exosomal tau was significantly higher in PD than in healthy control subjects (p=0.038) (Fig. 2a). A difference between PD and AD was also apparent, but did not achieve significance (p=0.064); no significant difference was observed between AD and healthy controls (p=0.975). Mean whole plasma tau concentrations, in contrast, were significantly higher in AD compared to PD (p<0.001) or healthy controls (p<0.001), in line with those reported in previous studies [22]; but there was no significant difference between PD and healthy controls (p=0.771) (Fig. 2b). No significant associations were identified between plasma exosomal tau and whole plasma tau concentrations in all subjects or in any of the three diagnostic groups.

Fig. 2. Evaluation of plasma exosomal tau concentrations in clinical samples.

Tau concentrations were measured using Quanterix Simoa and comparisons were performed for tau in L1CAM-containing exosomes isolated from plasma, total tau in whole plasma in patients with Alzheimer disease (AD; n=106), patients with Parkinson disease (PD; n=91) and healthy controls (CO; n=106). (a) Mean plasma exosomal tau was higher in PD than in healthy control subjects (p=0.038, ANOVA) and AD (p=0.064). (b) Mean whole plasma tau concentration, in contrast, was significantly higher in AD compared to PD (p<0.001) or healthy controls (p<0.001). (c) A significant correlation between the plasma exosomal tau and the disease duration was observed in PD patients (r=0.286, p=0.015, Pearson correlation). (d) Additionally, a significant correlation between the whole plasma tau and the disease severity indexed by the MMSE was observed in AD patients (r=−0.233, p=0.025). Tau concentrations were Log10 transformed to generate a more normally distributed dataset. *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001.

When all subjects were considered together, CSF tau species significantly correlated with whole plasma tau, but not plasma exosomal tau concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 5a, 5b). In PD subjects alone, plasma exosomal tau, but not whole plasma tau, significantly correlated with CSF t-tau (p=0.045) and p-tau (p=0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 5d, 5e).

In ROC analysis, plasma exosomal tau was modestly predictive in distinguishing PD from healthy controls (AUC = 0.607, sensitivity = 57.8%, specificity = 65.1%), which is similar to CSF tau, and PD versus AD (AUC = 0.584, sensitivity = 57.8%, specificity = 60.4%) (Supplementary Fig. 6a, 6b). On the other hand, whole plasma, but not exosomal, tau performed moderately in differentiating AD and healthy controls (AUC = 0.760, sensitivity = 65.1%, specificity = 78.3%) or AD and PD (AUC = 0.721, sensitivity = 69.0%, specificity = 68.9%) (Supplementary Fig. 6e, 6f).

Tau in L1CAM-containing exosomes was associated with disease duration (slope=0.0207, r=0.286, p=0.015; Fig. 2c), but not disease severity as assessed by Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor scores in patients with PD (Supplementary Fig. 7a). In contrast, whole plasma, but not exosomal, tau concentrations were associated with the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores in AD subjects (slope=−0.0103, r=−0.233, p=0.025; Fig. 2d; see also Supplementary Fig. 7 for other correlations).

4. Discussion

Kinetic analysis in this study suggests that the rapid translocation of icv-injected I-Tau from the brain/CSF to blood involves complex mechanisms, including both immediate entry into the blood and likely uptake by CNS cells, possibly for incorporation into endosomes/exosomes (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Exosomal transport was confirmed by the observation of radioactivity in exosomes isolated from plasma using anti-L1CAM-immunocapture enrichment of likely CNS-derived exosomes from plasma [9] and the fluorescence NTA analysis of L1CAM-containing exosomes isolated from tau-injected, tau KO mouse plasma. Both MS identification and immuno-detection further established tau in L1CAM-containing exosomes from human blood. The contribution of any potential non-specific binding of tau to the bead surface, IgGs or exosome surface appeared to be minimal based on the negative control data when normal IgG (IgG isotype control)-coupled beads were used (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3) and the NTA data on non-permeabilized exosomes (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, we believe this is the first direct evidence of transport of CNS tau into peripheral blood.

Using Simoa [18, 19], a substantially more sensitive technology than traditional ELISA or Luminex [20–22], we measured L1CAM-exosomal tau levels in the sub-pg/mL plasma range. This finding contrasts with a recent study [4], which reported an average of 100–200 pg/mL of tau within exosomes expressing NCAM or L1CAM. One possible explanation is that the published isolation technique, using thromboplastin-D and ExoQuick to enrich exosomes, is prone to introducing contaminating species. That said, even using the exosome isolation protocol as described in the publication, we have not been able to obtain similarly high tau levels using our well-characterized samples (see Supplementary Fig. 8 for more details).

Finally, in a relatively large cohort, we found that L1CAM exosomal tau levels in plasma were significantly elevated in PD patients as compared to controls, and notably but not significantly elevated compared to AD patients. Conversely, in contrast to the previous report that utilized NCAM (or L1CAM)-containing exosomes [4], no difference was observed in CNS-derived plasma exosomal tau between AD patients and healthy controls, despite that, consistent with other groups’ observations [22], whole plasma tau in our cohort was elevated in the AD group. We found that CNS-derived exosomal tau performed similarly to CSF t-tau or p-tau in distinguishing PD from healthy controls and AD. We also observed a significant correlation between plasma L1CAM exosomal tau in PD patients and disease duration. For AD patients, no such relationship was observed, although whole plasma tau correlated with MMSE scores. Thus, our results suggest CNS-derived plasma exosomal tau may be more an indicator of PD. As discussed previously [9], a caveat here is that although primarily expressed in the nervous system, L1CAM may also be found in a few cancer cells and certain specialized cells, including some kidney tubule epithelia [23–26]. However, most PD and AD patients of interest do not have cancers and our findings that both plasma exosomal α-synuclein [9] and tau (this study) correlated with PD severity (and in fact, performed better than CSF α-synuclein or tau) argue that any non-CNS-derived L1CAM-containing exosomes, even if present, likely do not represent the majority of existent species in plasma. That being said, additional investigation is warranted to further explore the sources of L1CAM-exosomes in blood and plasma exosomal tau in future experiments under physiological and pathological conditions.

These results also suggest differential efflux of tau in PD and AD, though the underlying mechanism(s) remains to be elucidated. Our mouse icv studies suggest that tau in the brain (CSF) may cross the CSF-blood barrier via exosomes; however, as we discussed in our previous publication [9], the CNS-derived tau (in L1CAM-containing exosomes) may enter the blood through other pathways, such as a dysfunctional or damaged bloodbrain barrier as has been suggested in PD patients [27, 28]. Our human data suggested either a differential CNS exosomal tau production or a differential tau clearance into peripheral blood between PD and AD. The difference in tau in PD and AD is not surprising, as tau pathology including alterations in p-tau has been identified in PD brains, though largely restricted to the striatum [7], unlike the global tau pathology observed in AD. Furthermore, contrasting those of AD or MCI patients [17], CSF concentrations of t-tau and p-tau are typically lower in PD patients compared to healthy controls [12, 29]. Based on the discovery of this investigation, one might speculate that higher CNS-derived exosomal tau levels in PD plasma might result from enhanced clearance of proteins (e.g., tau and α-synuclein [9]) via exosomes from the PD brain/CSF, which might also contribute to the lower CSF tau levels in PD. This clearance pathway to blood might be less active in AD, possibly contributing to increased CSF tau. Further confirmation is needed by using independent human samples or AD and PD mouse models.

Taken together, this study has revealed a novel tau transport pathway that may be important in modifying tau pathobiology. Our study also indicates a differential efflux of CNS tau to the peripheral blood between AD and PD patients and establishes the foundation for utilizing CNS-derived tau species, likely in combination with other candidates such as α-synuclein [9], as PD biomarkers in plasma exosomes.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Systematic review: The Pubmed database was searched to identify previously published research. There is a growing interest in understanding the clearance pathways that remove neurodegeneration-related protein species from neuronal cells and the brain. We previously reported that α-synuclein could be transported from the brain to the blood and central nervous system (CNS)-derived exosomal α-synuclein in plasma was relevant to Parkinson disease (PD). Work by another group later suggested that tau and amyloid β might be present in likely CNS-derived exosomes in plasma and increased in Alzheimer disease (AD).

Interpretation: Our findings provide first direct evidence demonstrating CNS tau efflux into the blood, with increased exosomal tau in PD but not in AD patients.

Future directions: Further characterizing this novel CNS tau clearance pathway in PD vs. AD could provide critical opportunities for future diagnostic and therapeutic interventions of tauopathies associated with various neurodegenerative disorders beyond AD and PD, such as traumatic brain injury.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate the participants for their generous donation of samples. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U01 NS082137, P30 ES007033-6364, R01 AG033398, R01 ES016873, R01 ES019277, R01 NS057567, and P50 NS062684-6221 to JZ, R21 NS085425 to MS, and R01 NS065070 to CPZ), partially by an Alzheimer’s Association grant (2015-NIRG-342009) to MS, and by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs (CPZ, ERP, JFQ, DRG, and WAB). It was also supported in part by the University of Washington's Proteomics Resource (UWPR95794). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH and other sponsors. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: J.Z., W.A.B. and M.S. supervised the project and designed the studies. A.K., K.M.B. and M.S. performed tau efflux experiments in mice. M.S. and A.A. conducted the NTA experiments. M.S., C.G. and A.K. performed exosome extraction and tau measurements in human samples. L.Y. and M.S. performed mass spectrometry analysis. C.G. and D.Z. performed comparison experiments using a published protocol. M.S., A.K., W.A.B. and K.F.K. conducted statistical analysis. C.G. and P.A. provided administrative and technical supports. C.P.Z., E.R.P., S.-C.H., J.F.Q., D.R.G. and T.J.M. characterized human subjects and provided plasma and CSF samples. M.S., T.J.C., J.Z., T.S. and W.A.B. drafted the manuscript; all authors critically reviewed the paper.

Conflicts of Interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:609–622. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medina M, Avila J. The role of extracellular Tau in the spreading of neurofibrillary pathology. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:113. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon D, Garcia-Garcia E, Gomez-Ramos A, Falcon-Perez JM, Diaz-Hernandez M, Hernandez F, et al. Tau overexpression results in its secretion via membrane vesicles. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10:73–75. doi: 10.1159/000334915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiandaca MS, Kapogiannis D, Mapstone M, Boxer A, Eitan E, Schwartz JB, et al. Identification of preclinical Alzheimer's disease by a profile of pathogenic proteins in neurally derived blood exosomes: A case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simón-Sánchez J, Schulte C, Bras JM, Sharma M, Gibbs JR, Berg D, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards TL, Scott WK, Almonte C, Burt A, Powell EH, Beecham GW, et al. Genome-wide association study confirms SNPs in SNCA and the MAPT region as common risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Hum Genet. 2010;74:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wills J, Jones J, Haggerty T, Duka V, Joyce JN, Sidhu A. Elevated tauopathy and alpha-synuclein pathology in postmortem Parkinson's disease brains with and without dementia. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Fischman AJ, Coy DH, Strauss SL. Carrier-mediated transport of enkephalins and N-Tyr-MIF-1 across blood-brain barrier. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:E477–E482. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1986.251.4.E477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi M, Liu C, Cook TJ, Bullock KM, Zhao Y, Ginghina C, et al. Plasma exosomal α-synuclein is likely CNS-derived and increased in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:639–650. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1314-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cholerton BA, Zabetian CP, Quinn JF, Chung KA, Peterson A, Espay AJ, et al. Pacific Northwest Udall Center of excellence clinical consortium: study design and baseline cohort characteristics. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3:205–214. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong Z, Shi M, Chung KA, Quinn JF, Peskind ER, Galasko D, et al. DJ-1 and alpha-synuclein in human cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2010;133:713–726. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi M, Bradner J, Hancock AM, Chung KA, Quinn JF, Peskind ER, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers for Parkinson Disease Diagnosis and Progression. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:570–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.22311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mata IF, Shi M, Agarwal P, Chung KA, Edwards KL, Factor SA, et al. SNCA variant associated with Parkinson disease and plasma alpha-synuclein level. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1350–1356. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi M, Zabetian CP, Hancock AM, Ginghina C, Hong Z, Yearout D, et al. Significance and confounders of peripheral DJ-1 and alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2010;480:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davson H, Segal MB. Physiology of the CSF and blood-brain barriers. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1996. The return of the cerebrospinal fluid to the blood: the drainage mechanism; pp. 489–523. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dragovic RA, Gardiner C, Brooks AS, Tannetta DS, Ferguson DJ, Hole P, et al. Sizing and phenotyping of cellular vesicles using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:780–788. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:403–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rissin DM, Kan CW, Campbell TG, Howes SC, Fournier DR, Song L, et al. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rissin DM, Fournier DR, Piech T, Kan CW, Campbell TG, Song L, et al. Simultaneous detection of single molecules and singulated ensembles of molecules enables immunoassays with broad dynamic range. Anal Chem. 2011;83:2279–2285. doi: 10.1021/ac103161b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neselius S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Randall J, Wilson D, Marcusson J, et al. Olympic boxing is associated with elevated levels of the neuronal protein tau in plasma. Brain Inj. 2013;27:425–433. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.750752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randall J, Mortberg E, Provuncher GK, Fournier DR, Duffy DC, Rubertsson S, et al. Tau proteins in serum predict neurological outcome after hypoxic brain injury from cardiac arrest: results of a pilot study. Resuscitation. 2013;84:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zetterberg H, Wilson D, Andreasson U, Minthon L, Blennow K, Randall J, et al. Plasma tau levels in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5:9. doi: 10.1186/alzrt163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenwrick S, Watkins A, De Angelis E. Neural cell recognition molecule L1: relating biological complexity to human disease mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:879–886. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiefel H, Bondong S, Hazin J, Ridinger J, Schirmer U, Riedle S, et al. L1CAM: a major driver for tumor cell invasion and motility. Cell Adh Migr. 2012;6:374–384. doi: 10.4161/cam.20832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debiec H, Christensen EI, Ronco PM. The cell adhesion molecule L1 is developmentally regulated in the renal epithelium and is involved in kidney branching morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:2067–2079. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allory Y, Matsuoka Y, Bazille C, Christensen EI, Ronco P, Debiec H. The L1 cell adhesion molecule is induced in renal cancer cells and correlates with metastasis in clear cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1190–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartels AL. Blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein function in neurodegenerative disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:2771–2777. doi: 10.2174/138161211797440122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai BS, Monahan AJ, Carvey PM, Hendey B. Blood-brain barrier pathology in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease: implications for drug therapy. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:285–299. doi: 10.3727/000000007783464731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang JH, Irwin DJ, Chen-Plotkin AS, Siderowf A, Caspell C, Coffey CS, et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 1–42, T-tau, P-tau181, and α-synuclein levels with clinical features of drug-naive patients with early Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1277–1287. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.