Abstract

Trans-acting regulators provide novel opportunities to study essential genes and regulate metabolic pathways. We have adapted the clustered regularly interspersed palindromic repeats (CRISPR) system from Streptococcus pyogenes to repress genes in trans in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002 (hereafter PCC 7002). With this approach, termed CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), transcription of a specific target sequence is repressed by a catalytically inactive Cas9 protein recruited to the target DNA by base-pair interactions with a single guide RNA that is complementary to the target sequence. We adapted this system for PCC 7002 and achieved conditional and titratable repression of a heterologous reporter gene, yellow fluorescent protein. Next, we demonstrated the utility of finely tuning native gene expression by downregulating the abundance of phycobillisomes. In addition, we created a conditional auxotroph by repressing synthesis of the carboxysome, an essential component of the carbon concentrating mechanism cyanobacteria use to fix atmospheric CO2. Lastly, we demonstrated a novel strategy for increasing central carbon flux by conditionally downregulating a key node in nitrogen assimilation. The resulting cells produced 2-fold more lactate than a baseline engineered cell line, representing the highest photosynthetically generated productivity to date. This work is the first example of titratable repression in cyanobacteria using CRISPRi, enabling dynamic regulation of essential processes and manipulation of flux through central carbon metabolism. This tool facilitates the study of essential genes of unknown function and enables groundbreaking metabolic engineering capability, by providing a straightforward approach to redirect metabolism and carbon flux in the production of high-value chemicals.

Keywords: CRISPRi, tunable, cyanobacteria, lactate, chemical production, carboxysome, phycobilisome, synthetic biology

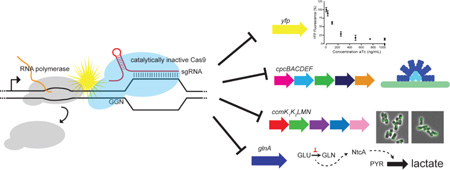

Graphical Abstract

1.1 Introduction

The ability to manipulate and predictably control gene expression is an essential tool for engineering metabolism and biology. Modern gene expression toolboxes include promoter libraries for initiating transcription at desired rates (Alper et al., 2005; Markley et al., 2015), transcriptional regulator/operator pairs for creating dynamic switches and circuits (Stanton et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012), transcription terminators for insulating neighboring expression cassettes (Chen et al., 2013) models of translation initiation for engineering ribosome binding sites (Espah Borujeni et al., 2014; Salis et al., 2010), codon optimization algorithms for optimizing gene sequences (Puigbò et al., 2007), and RNA structures that tune mRNA turnover, termination, and translation initiation (Pfleger et al., 2006). These tools have enhanced the study of natural systems and enabled the creation of engineered microbes for addressing societal challenges such as sustainable chemical production (Chubukov et al., 2014; Hara et al., 2014; Liao et al., 2016; Lynch and Gill, 2012; Smanski et al., 2016). Unfortunately, differences in how microbes recognize promoters, regulate gene expression, and translate protein do not allow genetic circuits and tools to be universally moved between organisms with the desired outcome. Instead synthetic biology tools must be validated in new hosts and then frequently adapted and refined for optimal functionality (Keasling, 2012).

The majority of established tools regulate genes in cis and require replacement of native expression cassettes with heterologous sequences to alter the level of gene expression. Replacing sequences has the unfortunate side-effect of removing native regulation that has often evolved to optimize the protein abundance needed for a given set of natural physiological states. In many instances, the native context is ideal for one state but needs to be altered for a new unnatural state (e.g. chemical production instead of growth). Trans acting tools that supersede native regulation in specific environments are therefore desirable additions to the synthetic biology toolbox (Copeland et al., 2014). One such tool, termed CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), takes advantage of the adaptive RNA-based defense system that in many bacteria targets and cleaves foreign nucleic acids such as viruses and plasmids (Qi et al., 2013). Diverse CRISPR-Cas systems exist in bacteria with altered locus architecture, components, maturation processes, and functions (Makarova et al., 2015). The type II system from Streptococcus pyogenes has been the most widely adapted to manipulate gene expression. A complex of a single guide RNA (sgRNA) containing a sequence complementary to the target and the protein Cas9 DNA nuclease protein can initiate double-stranded breaks. Point mutations in the two active sites can be used to create a nuclease deficient or dead Cas9 (dCas9). The complex of the sgRNA and dCas9 is still able to bind target DNA and can be used to either repress or activate gene expression (Bikard et al., 2013). There is strong evidence that repression is caused by the dCas9-sgRNA complex sterically blocking RNA polymerase elongation (Gilbert et al., 2013). The use of CRISPRi in Escherichia coli has led to efficient repression of targets as high as 300-fold when the sgRNA was targeted to the non-template strand near the 5’ end of the gene with no detectable off-target affects (Qi et al., 2013). This repression was reversible and can be multiplexed to target several genes simultaneously.

CRISPRi has become an increasingly attractive alternative to other trans-acting regulators repressor proteins such as trans-activator-like effectors (TALEs) or zinc fingers, due to the simplicity of design and ease of synthesis. By altering just 20 nucleotides of the sgRNA, the system can be designed to repress any gene of interest. However, it is necessary to choose a target site with a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) which is 5’-NGG-3’ for S. pyogenes Cas9, but engineered Cas9 nucleases are reducing this constraint (Kleinstiver et al., 2015). Despite this limitation this technology has been used to repress reporter genes as well as enhance titers of products in various organisms: flavonoids in E. coli (Wu et al., 2015) and L-lysine and L-glutamate in Corneybacterium glutamicum (Cleto et al., 2016).

Here, we adapted this technology to an industrially relevant cyanobacterial strain, Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002 (PCC 7002) (Devroe et al., 2010; Reppas and Ridley, 2011). Cyanobacteria are an attractive chassis for chemical production that enables direct conversion of carbon dioxide and sunlight into useful products (Oliver and Atsumi, 2014). PCC 7002 is a promising strain of cyanobacteria because it grows rapidly, is halotolerant, is naturally transformable, can tolerate high light conditions, and has a growing synthetic biology toolbox (Markley et al., 2015; Zess et al., 2016). To add to the PCC 7002 toolbox, we developed a tunable gene repression system using CRISPRi. The system is novel because targets can be repressed to varying degrees by controlling the expression of CRISPRi components with an inducer, anhydrotetracycline (aTc). Most CRISPRi systems including one developed for another cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, can be turned on and off but the ability to titrate the levels of expression was not reported (Yao et al., 2015). Attempts have been made to tune repression by introducing mismatches in the sgRNA, but this involves making numerous strains to reach a variety of repression levels (Qi et al., 2013).

The ability to finely tune native gene expression will be critical for manipulating essential genes and to achieve growth regimes that decouple biomass and chemical production for maximum yield (Xu et al., 2014). In many cases, intermediate levels of enzyme expression result in maximum product titer (Freed et al., 2015; Pitera et al., 2007). With the described CRISPRi technology we can lower expression of essential cyanobacterial genes, decrease but not abolish flux towards competing products, and manipulate cellular processes to varying degrees. Here, we demonstrate the utility of finely tuning native gene expression by downregulating the abundance of phycobilisomes. In addition, we create a conditional auxotroph by repressing synthesis of the carboxysome, an essential component of the carbon concentrating mechanism cyanobacteria use to fix atmospheric CO2. Lastly, we demonstrate a novel strategy for increasing central carbon flux by conditionally downregulating a key node in nitrogen assimilation pathways. The resulting cells produced 2-fold more lactate than a baseline engineered cell line, representing the highest photosynthetically generated productivity to date.

1.2 Materials and Methods

1.2.1 Chemicals, reagents, and media

Strains were grown and maintained on media A+ media (Stevens et al., 1973) with 1.5% (w/v) Bacto-Agar (Fisher). Strains with antibiotic resistance markers were selected on media with antibiotics (kanamycin, 100 µg/mL; gentamicin, 30 µg/mL) and strains with cassettes introduced in the acsA locus were plated on 100 µM acrylic acid. Strains were grown in glass culture tubes (2 × 15 cm) with 20 mL media A+ and bubbled with either air (0.04% CO2) or high CO2 (10% CO2). Temperature was maintained at 38°C and light intensity was approximately 150 umol photons m−2s−1. Optical density was measured in a Genesys 20 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) in 1-cm cuvette.

1.2.2 Strain Construction

All strains, plasmids, and plasmid sequence used in this study are in the supplementary material. Plasmids were cloned in Escherichia coli DH5α. The sequences of chromosomal cassettes are available as supplementary material. Genes and sgRNA were transformed onto the chromosome of wild-type PCC 7002 using homologous recombination. dCas9 was introduced at the acsA locus (Begemann et al., 2013) and the sgRNA and a kanamycin resistance marker were introduced at the NS1 site (Davies et al., 2014). In some strains EYFP or the LDH with the PcLac143 inducible promoter system were placed in the glpK pseudogene along with a gentamicin resistance marker (Begemann et al., 2013). Constructs were made using Gibson assembly (Gibson et al., 2009) with regions of homology added in the 5’ end of the primers. Site specific mutations in LDH enzymes was based on the V39R mutation described for the L-LDH of B. subtilis strain 168 (Richter et al., 2011). In the case of the B. subtilis LDH, the point mutation was made by site-directed mutagenesis protocol (Ho et al., 1989) with overlap extension PCR and specific primers, followed by a DpnI treatment and transformation to chemically competent E. coli DH5α. Some sgRNA were instead made by adding the 20 nucleotide target sequence in the 5’ region of an oligonucleotide primer and amplifying all of the way around a previously constructed plasmid to create one linear piece. After purification, PCR products were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (NEB) to form circular plasmids. sgRNAs targeting the non-template strand were picked with DNA 2.0’s gRNA designer by entering a gene of interest. Potential target sequences with a NGG PAM sequence within the first 500 nucleotides from the start codon were used in a BLAST search against the wild-type PCC 7002 genome to ensure no substantial off target effects. Binding sites of sgRNA can be found in the supplementary material.

1.2.3 Measurement of Fluorescence

Cultures (20 mL media A+) were bubbled with air for 24 hours before being diluted in triplicate to OD730nm = 0.5 in 10 mL of media A+. Cultures were bubbled for 24 hours to an OD730nm ~ 1 where 1.5 OD730nm-mLs were spun down at 1,400xg for 10 minutes. Cell lysis with Bugbuster and fluorescence measurements on a Tecan M1000 plate reader were performed as described previously (Markley et al., 2015).

1.2.4 Reversibility Test

Cultures (20 mL media A+) were inoculated from fresh plates and bubbled with air for 48 hours. Cultures were diluted to ~ 0.1 OD730nm-mL in 20 mL A+ in quadruplicate and 1 µg/mL aTc was added where indicated. A fluorescence measurement of 200 µl of cells was taken in a Tecan M1000 plate reader with a gain of 200. Cultures were spun down at 5000xg for 10 min in a Beckman Coulter Allegra X-15R Centrifuge, washed once with A+ media, and resuspended in the same volume of A+ media to maintain a constant cell density pre- and post-wash.

1.2.5 Measurement of Absorbance

Cultures (20 mL media A+) were bubbled with air for 24 hours before being diluted in triplicate to OD730nm = 0.5 in 10 mL of media A+ with aTc added where indicated. Cultures were bubbled for 24 hours with air before an absorbance scan (300–750 nm) was conducted in 96 well plates with a working volume of 200 ul using a Tecan M1000 plate reader.

1.2.6 Spot Plating

Cultures (20 mL media A+) were inoculated from plates and grown with 10% CO2 for 24 hours. Cultures were diluted to OD730nm = 0.5 in 20 mL A+, aTc was added where indicated, and bubbled for another 24 hours with 10% CO2. Samples were suspended at OD730nm = 0.01 as measured by a Genesys 20 spectrophotometer, 10-fold serially diluted in media A+, and spotted onto solid media (7µl/spot).

1.2.7 Fluorescence Microscopy

Cultures (20 mL media A+) were inoculated from plates and bubbled with 10% CO2 for 24 hours with aTc where indicated. Cultures were diluted to OD730nm = 0.05 in 20 mL media A+ and aTc was added where indicated, and bubbled for another 24 hours with 10% CO2. Cultures were diluted to OD730nm = 0.05 in 20 mL A+ with aTc and grown with 10% CO2 for 5 hours before visualizing. Cells (2 µl) were spotted onto 1% (w/v in media A+) agarose pads in a 16-well chamber slide (Nunc™ Lab-Tek™, Scotts Valley, CA), air-dried, and covered with a 0.17 mm coverslip. Images were acquired on a Zeiss Axioimager Z2 for GFP (excitation: BP 470/40 nm; beam splitter: FT 495 nm; emission: BP 525/50 nm), and brightfield using a 100X oil-immersion objective (NA = 1.3). Images were analyzed with ImageJ (Abràmofff et al., 2005).

1.2.8 Lactate Quantification

Cultures (10 mL A+ media A+) were inoculated from plates and bubbled with air for 24 hours before being diluted in duplicate to OD730nm = 0.05 in 15 mL of media A+, induced with 1 mM IPTG, and bubbled with either air (0.04% CO2) or high CO2 (1% CO2). Temperature was maintained at 38°C and light intensity was approximately 250 umol photons m−2s−1. Samples were withdrawn periodically for biomass and lactate measurements, centrifuged, and the supernatant was stored at −20°C until quantification by HPLC (Shimadzu Co., Columbia, MD, USA) equipped with a quaternary pump, autosampler, vacuum degasser, photodiode array and refractive index detector. HPLC separations were performed using an Ultra Aqueous C18 column (Restek). The HPLC operating conditions were as follows: mobile phase: 50 mM KH2PO4 (pH 2.5 with 1% Acetonitrile), flow rate 0.100 mL/min, column temperature 30°C, photodiode array detector at 210 nm, run time: 10 minutes, injection volume 10 µL. Organic acids were quantified by comparison with peaks generated by known amounts of lactate sodium salt (Sigma) in Media A+. Dry cell weight concentrations were estimated from OD730nm values using a standard curve created from lyophilized cell pellets (1 OD730nm = 1.409 g/L; R2=0.9852). Biomass productivity was calculated over the time course using a linear fit. Lactate concentrations for each individual culture are plotted with respect to time and a linear fit was applied.

1.3 Results and Discussion

1.3.1 Optimization of YFP Repression with CRISPRi

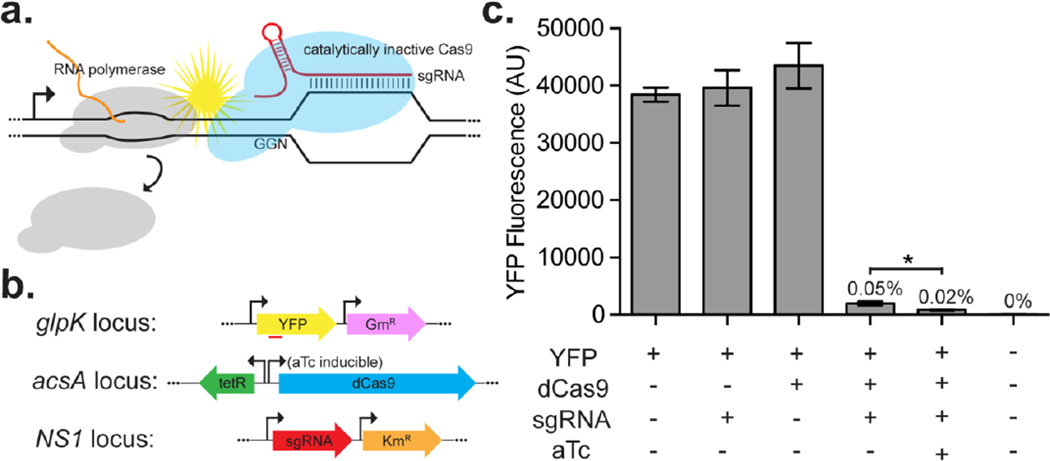

To demonstrate a functional CRISPRi system in PCC 7002 we integrated three expression cassettes into the chromosome: 1) a fluorescent reporter, 2) an inducible dCas9, and 3) a constitutively expressed sgRNA (Figure 1a). We constructed a reporter cassette consisting of a heterologous yellow fluorescence protein (EYFP) expressed from a strong constitutive promoter and a gentamicin resistance marker. The resulting cassette was integrated into a neutral site in the genome by replacing the glpK pseudogene and selecting transformants on gentamicin. We integrated dCas9 under the control of the anhydrotetracycline (aTc) induction system, EZ3 (Zess et al., 2016) into the acsA locus using acrylic acid as a counter selection marker (Begemann et al., 2013). The aTc-controlled promoter was critical to construct the system; no transformants were obtained when strains were transformed with a plasmid containing dCas9 expressed from the stronger cLac94 IPTG-inducible promoter (Markley et al., 2015). A single guide RNA (sgRNA) was designed to target the non-template strand of YFP at a position ~175 nucleotides downstream of the start codon. An expression cassette containing the sgRNA expressed from the strong constitutive promoter, PJ23119, was integrated onto the chromosome at neutral site 1 (NS1) with a kanamycin resistance marker (Davies et al., 2014). We measured bulk YFP fluorescence in extracts from these strains and found that the fluorescence levels were unaffected in strains containing only dCas9 or the sgRNA (Figure 1b) even when expression of dCas9 was induced with aTc (Supplemental Figure 1). In strains containing all three cassettes, YFP fluorescence was reduced to 0.05% of the unregulated control. In the presence of 1 µg/mL aTc (to induce dCas9 expression), YFP fluorescence was further reduced to 0.02% of the control. These data confirm that CRISPRi functions in PCC 7002, however the limited dynamic range of the system limits the utility in many applications.

Figure 1.

Repression of YFP reporter with CRISPRi. (a) Cartoon illustrating how the dCas9-sgRNA complex interferes with RNA polymerase, thereby repressing transcription. (b) Schematic of the three cassettes used to implement CRISPRi in PCC 7002. (c) YFP fluorescence of PCC 7002 extracts containing dCas9 expressed from the aTc-inducible promoter and sgRNA targeting YFP from constitutive PJ23119. Repression requires the presence of both dCas9 and sgRNA but is not dependent on the presence of the inducer, aTc. Induction of dCas9 caused a significant decrease in YFP fluorescence (p = 0.0008, unpaired two-tailed t-test with equal standard deviation). Numbers above each bar report the percent fluorescence relative to the YFP only strain. Error bars represent standard deviation of fluorescence measured from four biological replicates.

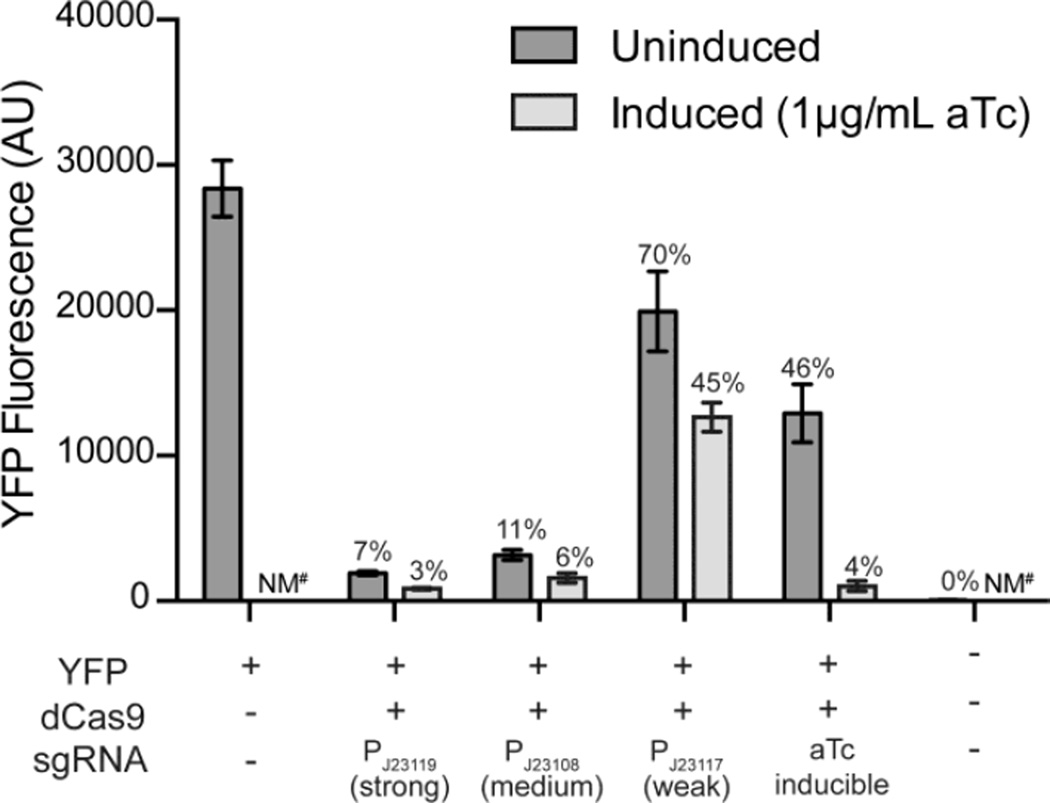

In effort to increase the dynamic range of the CRISPRi system, we hypothesized that decreasing expression of the sgRNA and dCas9 would reduce repression in the absence of aTc. Therefore, we replaced the promoter controlling expression of dCas9 with weaker alternatives, but saw no reduction in repression in the absence of aTc (Supplemental Figure 2). Similarly, we changed the promoter strength of the sgRNA from a strong promoter, PJ23119, to a medium constitutive promoter, PJ23108, a weak constitutive promoter, PJ23117, and the same aTc-inducible system (Zess et al., 2016) controlling dCas9 expression (Figure 2). We found that decreasing the sgRNA promoter strength reduced the repression of YFP in the uninduced culture (from 7% of the control for PJ23119, to 11% for PJ23108, and 70% for PJ23117), but also in the induced samples (from 3% of the control for PJ23119, to 6% for PJ23108, and 45% for PJ23117). In contrast, expression of the sgRNA under control of the aTc-inducible system (Zess et al., 2016) already controlling dCas9, generated the largest dynamic range. The YFP fluorescence of the uninduced sample was reduced to 46% of the control and the induced sample maintained strong repression of YFP (4% of the control).

Figure 2.

The dynamic range of the system is improved when both dCas9 and sgRNA are controlled by EZ3 tet promoters. Bars show YFP fluorescence of extracts containing dCas9 expressed from the aTc-inducible promoter and sgRNA targeting YFP from constitutive promoters of varying strength and an aTc-inducible promoter. Promoter strengths were previously characterized in PCC 7002 (Markley et al., 2015). The percent fluorescence relative to the YFP only strain is displayed above the bar. Averages of strains grown in quadruplicate are shown (error bars show standard deviation, NM# indicates not measured).

Due to the required tet operator, the resultant sgRNA from the aTc-inducible system has an additional 7 nucleotides at the 5’ end. When those same 7 nucleotides were added to the 5’ of the sgRNA expressed from PJ23119 there was no change in YFP repression (Supplemental Figure 3). This finding suggests that CRISPRi in PCC 7002 may be tolerant to mis-matched extra nucleotides at the 5’ end of the sgRNA in contrast to examples in other bacteria where 5’ extensions decrease the efficiency of repression (Larson et al., 2013).

We hypothesize that minimizing both dCas9 and sgRNA concentrations relieve the unintended repression when dCas9 is uninduced. In other words, very small concentrations of dCas9 may be capable of effectively silencing YFP expression when excess sgRNA is present. Attempts to reduce dCas9 expression using an alternate promoter and by deleting the promoter region were unsuccessful, suggesting that residual or promiscuous expression of dCas9 is sufficient for full repression (Supplemental Figure 3).

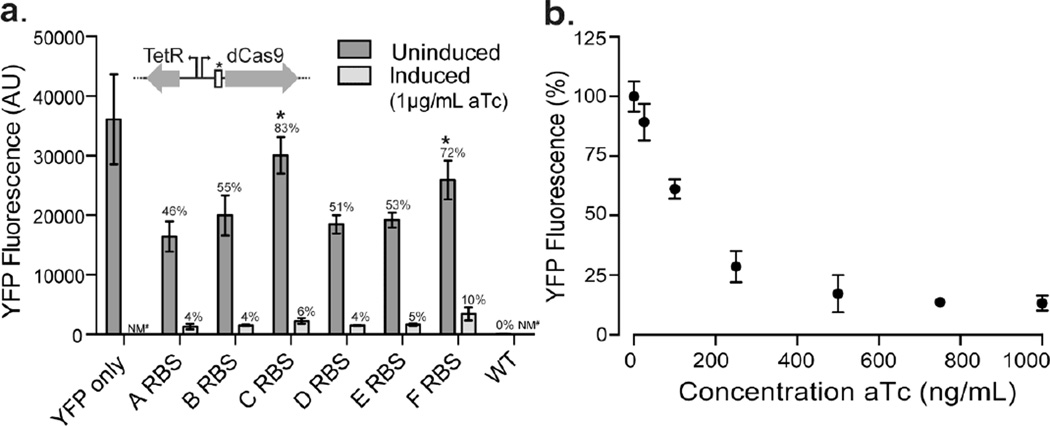

We next sought to improve this tunable repression by decreasing repression of the target gene in the absence of aTc. We hypothesized that reducing the expression level of dCas9 by altering its ribosome binding site (RBS) would meet this goal. Using the RBS Library Calculator (Farasat et al., 2014) we designed five additional RBS with predicted decreasing translation initiation rates (labeled A-F). We achieved a range of repression in the uninduced samples although they did not correspond to the predicted translation initiation rate of dCas9 (Figure 3A). Altering the dCas9 RBS allowed us to obtain minimal repression without aTc (~30%) while maintaining repression when maximally induced (~90%). In an effort to further optimize the system, we created 5’ truncations of the sgRNA as this has been shown to lower repression in other systems ((Qi et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2015). Here, we observed a drastic decrease in repression between 15 nucleotides and 12 nucleotides, but overall dynamic range was not improved relative to the original 20 nucleotide sgRNA system (Supplemental Figure 4). We proceeded to characterize the strain with the “F” RBS controlling dCas9 expression (there was no statistical difference in YFP fluorescence between uninduced samples of “C” and “F” RBS). With the uninduced samples normalized to 100%, we were able to titrate YFP fluorescence to 13% when fully induced (Figure 3B). There is still some repression in the uninduced sample (~30% of no CRISPRi control). Last, we designed sgRNA to target different locations within YFP and found similar results for sgRNA targeting both the template and non-template strands near the beginning of the transcript, with slightly reduced repression when fully induced when targeting the 3’ end of the transcript (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Decreasing RBS strength of dCas9 maximizes the dynamic range and enables titration of repression. (a) Bars show YFP fluorescence of cultures with different ribosome binding sites (RBS) controlling translation of dCas9. RBS’ were designed to be in decreasing strength, A to F. A one-way ANOVA showed statistical significance between uninduced samples (p < 0.0001), but not when C and F RBS were removed. There was no statistical difference between uninduced samples of C and F RBS (p = 0.115 unpaired two-tailed t-test with equal standard deviation). Data are the average of biological quadruplicates and error bars show standard deviation. (b) Titration of strain with F RBS with increasing concentrations of aTc. Averages of strains grown in triplicate are shown with the uninduced sample normalized to 100% (error bars show standard deviation).

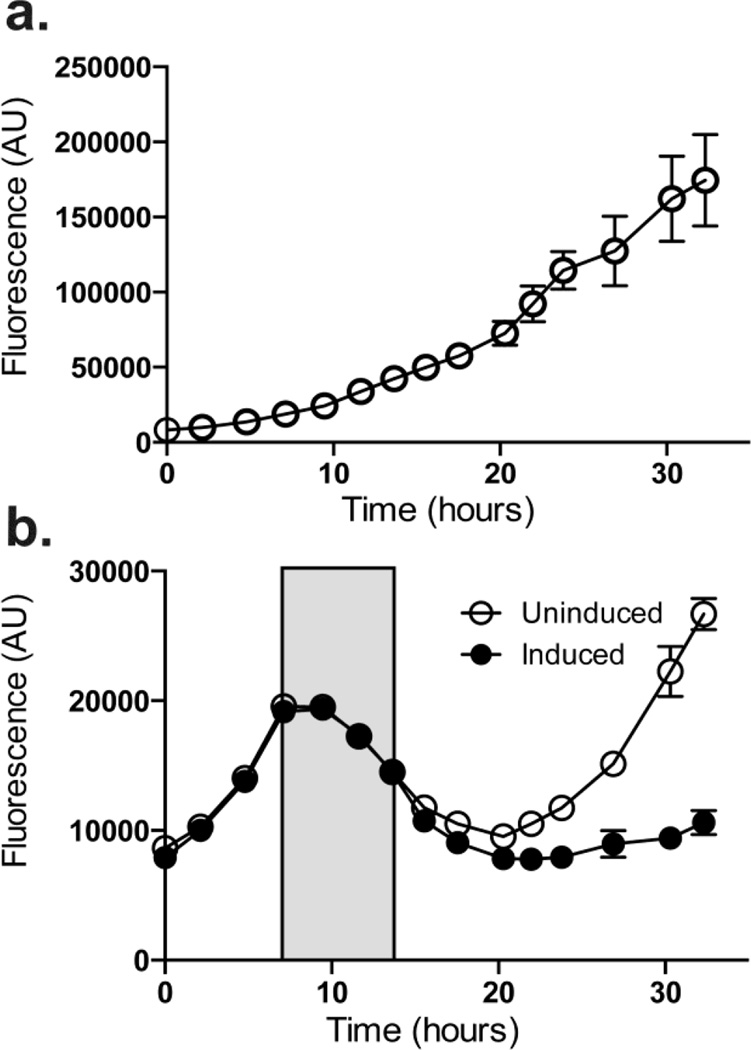

1.3.2 Reversibility of repression

One advantage of trans-acting regulators is the potential to dynamically regulate expression of target genes between on and off states in the same culture. To examine the potential of the CRISPRi system in this regard, we performed a series of timecourse experiments wherein aTc levels were either added or removed as specific timepoints and YFP fluorescence was monitored. In the absence of aTc, YFP fluorescence increased over time (Figure 4a) as expected. When cultures were induced, (Figure 4b), YFP fluorescence decreased over time as cells grew (filled in markers). Cultures were centrifuged, washed, and resuspended in fresh media with or without aTc. In the absence of aTc, YFP fluorescence returned, albeit at a slower rate than the completely uninduced cultures (Figure 4a). In contrast, induced cultures maintained a lower level of YFP fluorescence for the remainder of the experiment. The increasing fluorescence in the samples without aTc shows that CRISPRi can be turned on and off by the addition or removal of aTc. This tool enables the study of PCC 7002 genes allowing the knockdown of genes to intermediate levels as well as the ability to track physiological changes throughout time when repressing or depressing genes of interest.

Figure 4.

CRISPRi repression can be reversed. (a) YFP fluorescence increases over time in cultures grown without aTc. (b) YFP fluorescence increases over time before the addition of aTc (marked with arrow), where YFP fluorescence begins to decrease. Upon removal of aTc by centrifugation and washing, YFP fluorescence begins to increase again in cells without aTc (open boxes), but is maintained at a lower level when aTc was re-added (dark diamonds). Experiments were performed in quadruplicate with the average fluorescence values marked and the standard deviation shown as the errors bars. Data for panels A & B were collected at the same time using the same detection settings.

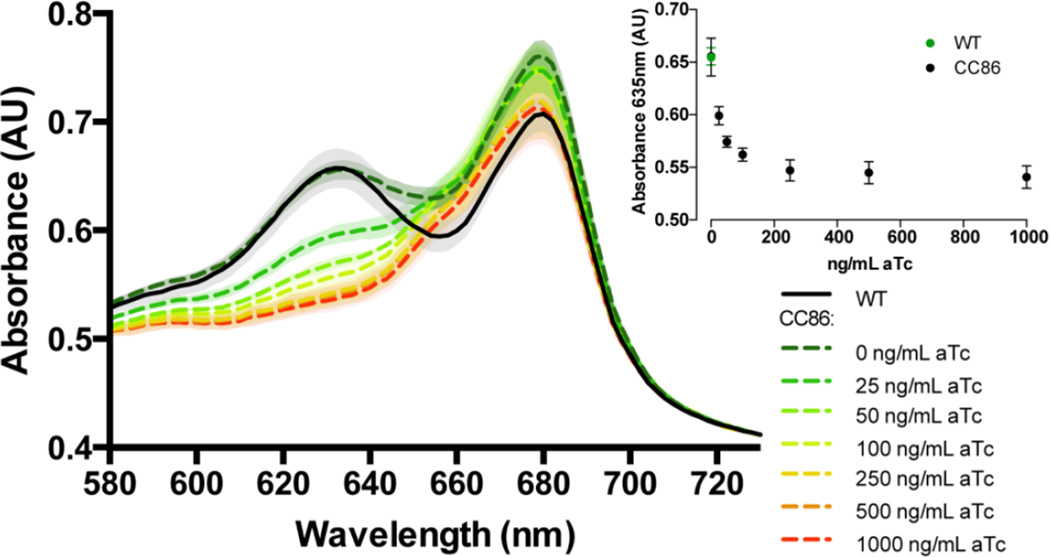

1.3.3 Repression of native genes

We tested whether CRISPRi could be used to rapidly modulate two key processes in photosynthetic organisms: light harvesting and CO2 fixation. First, we designed a system to target and repress expression of core phycobilisome genes. Phycobilisomes are multi-subunit pigment-protein complexes that function as light harvesting antennae in cyanobacteria by transferring light energy to the photosynthetic reaction centers, photosystem I and photosystem II (Grossman et al., 1993; Liu et al., 2013). The phycobilisome is comprised of an allophycocyanin core attached to peripheral rods assembled from disks of phycocyanin separated by linker polypeptides. In PCC 7002, the cpcBACDEF operon encodes the major components of the peripheral rods including the α-(CpcA) and β-subunits (CpcB) of phycocyanin, the rod linkers (CpcC and CpcD), and two proteins involved in attachment of the phycocyanobilin pigment to the α-phycocyanin subunit (CpcE and CpcF) (Bryant et al., 1990). Since reduction of antennae size has been a promising strategy for increasing light penetration into high-density cyanobacterial cultures (Kirst et al., 2014), we designed an sgRNA to target cpcB and inhibit transcription of the entire cpcBACDEF operon. Others have shown that when the rod proteins are deleted there is a decrease in absorbance corresponding to phycocyanin at 635 nm (Lea-Smith et al., 2014). We hypothesized that repression of this operon would lead to an observable phenotype – a decrease in absorbance in the phycocyanin absorbance peak at 635 nm relative to the 680 nm chlorophyll peak (Alvey et al., 2011).

Following induction of the dCas9 in the strain containing the sgRNA targeting cpcB, we observed a significant decrease in the absorption peak at 635 nm, indicating a severe depletion phycobilisomes compare to the control strain (Figure 5). Dynamic modulation of the light-harvesting complex, as shown by our CRISPRi strategy, could be useful for improving growth at high cell density (Kirst et al., 2014) without affecting initial biomass scale-up that could be reduced in a mutant lacking phycobilisomes. Moreover, CRISPRi may be advantageous compared to making traditional deletion strains due to challenges in isolating homoplasmic strains, especially when the deletions have impacts on cellular fitness; for example, we were unable to generate a fully segregated cpcB strain, but could phenocopy this trait using CRISPRi (Lea-Smith et al., 2014).

Figure 5.

Tunable repression of the phycobilisome operon cpcBACDEF. A portion of the absorption spectra of PCC 7002 (CC86) cultures induced with different levels of aTc shows a decrease in the peak at 635 nm corresponding to the phycocyanin maximum absorbance peak. Average spectra are shown and were normalized to OD730nm = 0.4 (standard deviations displayed with shading). The inset shows the absorbance at 635 nm with different concentrations of aTc.

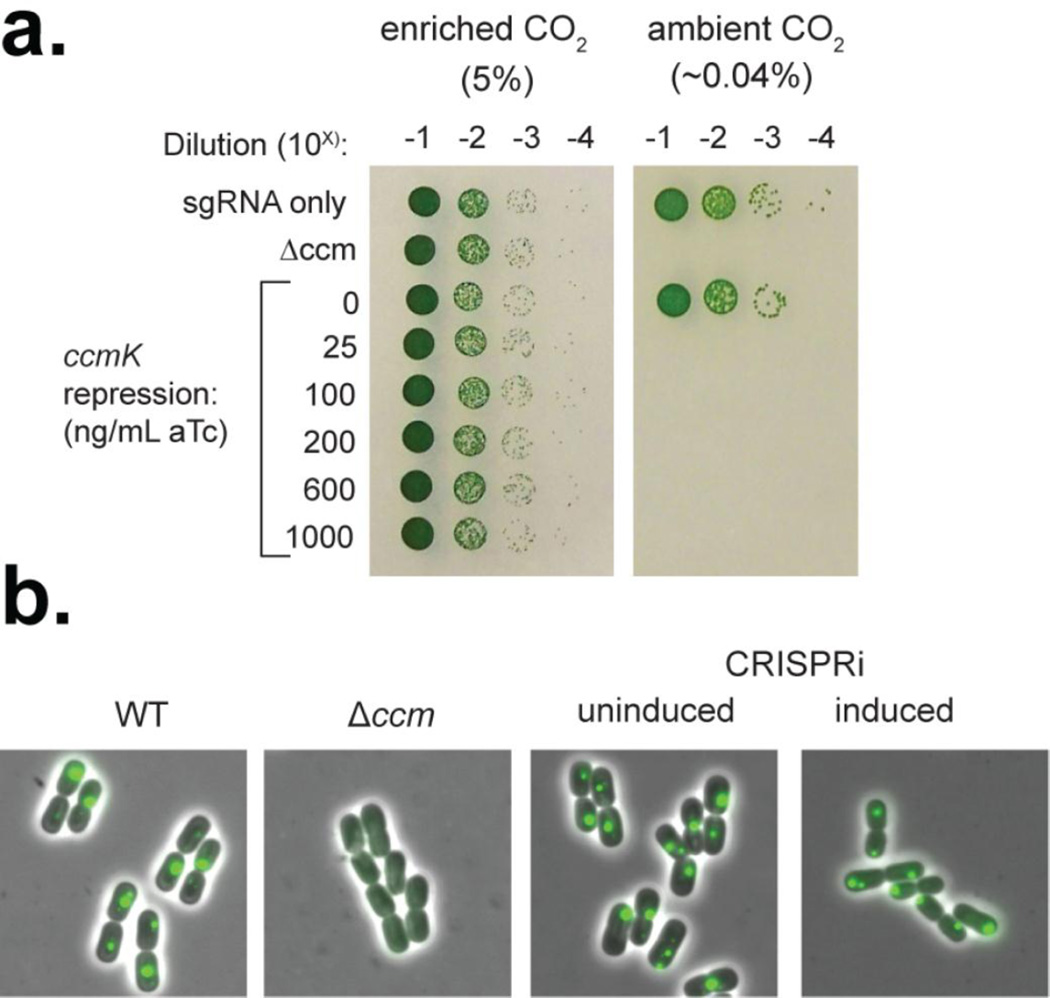

Next, we tested whether essential genes could be repressed using the CRISPRi system. In all free-living cyanobacteria and some chemoautotrophic bacteria, CO2-fixation occurs within the carboxysome, a bacterial microcompartment comprised entirely of protein that functions as a primitive organelle (Yeates et al., 2008). The carboxysome is comprised of a thin, multi-subunit, semi-permeable protein shell that encapsulates the key carboxylase, Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO), and carbonic anhydrase in a unique sub-cellular environment (Cameron et al., 2013). The carboxysome functions at a key component of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism, which increases the local concentration of CO2 at the site of CO2-fixation within the carboxysome.

While carboxysomes are essential for growth in atmospheric CO2 levels (0.04%), models predict that increased productivities could be achieved using un-encapsulated RuBisCO during growth in industrial conditions that provide high-CO2 (Clark et al., 2014), including flue gas from a coal-fired power plant (~15%). In PCC 7002, the ccm operon (ccmK1K2LMN) encodes the hexameric shell proteins (CcmK1 and CcmK2), the pentameric vertex protein (CcmL), and the interior scaffold proteins (CcmM and CcmN) that make up the major structural subunits of the carboxysome (Ludwig et al., 2000). We designed a sgRNA to target ccmK1, with the prediction that inhibition of the ccm operon would inhibit formation of the carboxysome, resulting in a strain with a high-CO2 requiring (HCR) phenotype and RuBisCO localized to the cytoplasm instead of being encapsulated within the carboxysome shell (Cameron et al., 2013).

We tested this hypothesis by comparing growth of a mutant lacking the ccmK1K2LMN (Δccm) operon with a CRISPRi strain targeting ccmK and a control containing the sgRNA but no dCas9 on solid medium in air or elevated CO2. Cultures were grown overnight in elevated (~10%) CO2, diluted and re-grown in the absence or presence of aTc, and then serially diluted and spot-plated onto solid media placed in either elevated CO2 or air. As expected, the control strain with only the sgRNA could grow in both high CO2 and air whereas Δccm could only grow with high CO2 (Figure 6a). While the undinduced CRISPRi strain could grow in both air and high CO2, the presence of aTc in the pre-culture resulted in a HCR phenotype, indicating functional repression of carboxysome assembly.

Figure 6.

Repression of the ccm operon. (a) Spot plates of control and ccmK repression strains grown in enriched CO2 and ambient CO2. Liquid cultures were grown with or without aTc with ~10% CO2 and normalized before spot-plating on solid media (without aTc). Δccm is able to grow with enriched CO2 but is unable to grow with ambient CO2 The uninduced ccmK repression strain could survive in air but those induced could not. (b) RbcL-sfGFP was used to visualize carboxysomes in control and ccmK repression strains.

To investigate whether assembly of the carboxysome was being inhibited, we expressed a C-terminal sfGFP fusion of the RuBisCO large subunit, rbcL, as a visual marker in the test strains. The uninduced CRISPRi strain resembled wild type (WT) with discrete fluorescent foci, indicating the presence of carboxysomes (Figure 6b), whereas the Δccm strain exhibited diffuse fluorescence. The induced strain resembled an intermediate between the WT and Δccm strains, with polar fluorescent foci and diffuse GFP signal. We suspect that the foci represent an intermediate in carboxysome assembly pathway initiated by molecular scaffolding of RuBisCO by CcmM; this intermediate is the result of insufficient shell proteins and exhibits an HCR phenotype (Cameron et al., 2013). Based on the HCR and visual phenotypes of the induced strains, we hypothesize that repression of the entire ccm operon is incomplete, but sufficient to inhibit assembly of functional carboxysomes.

1.3.4 Improving lactate production with CRISPRi

Trans-acting regulators also have the potential to implement elegant regulatory strategies in cell factories. Here, we used CRISPRi to increase the production of lactate. Lactate is an excellent model compound for studying metabolic engineering strategies in photoautotrophic bacteria because its synthesis pathway is short (one step removed from central metabolism) and consumes cofactors within the range generated by photosynthesis during linear electron transport (Oliver and Atsumi, 2014). PCC 7002 has an endogenous lactate dehydrogenase, but autotrophic cultures produce negligible levels of lactate under optimal laboratory conditions. Therefore we expressed an engineered version of the Bacillus subtilis lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) with a previously described single amino acid substitution (Richter et al., 2011), that switches the cofactor requirement of the enzyme from NADH to NADPH during conversion of pyruvate to lactate. An expression cassette with LDH under the control of the PcLac143 IPTG-inducible system (Markley et al., 2015) was integrated into the chromosome at the glpK pseudogene locus along with a gentamicin resistance marker to generate the base strain, CC133.

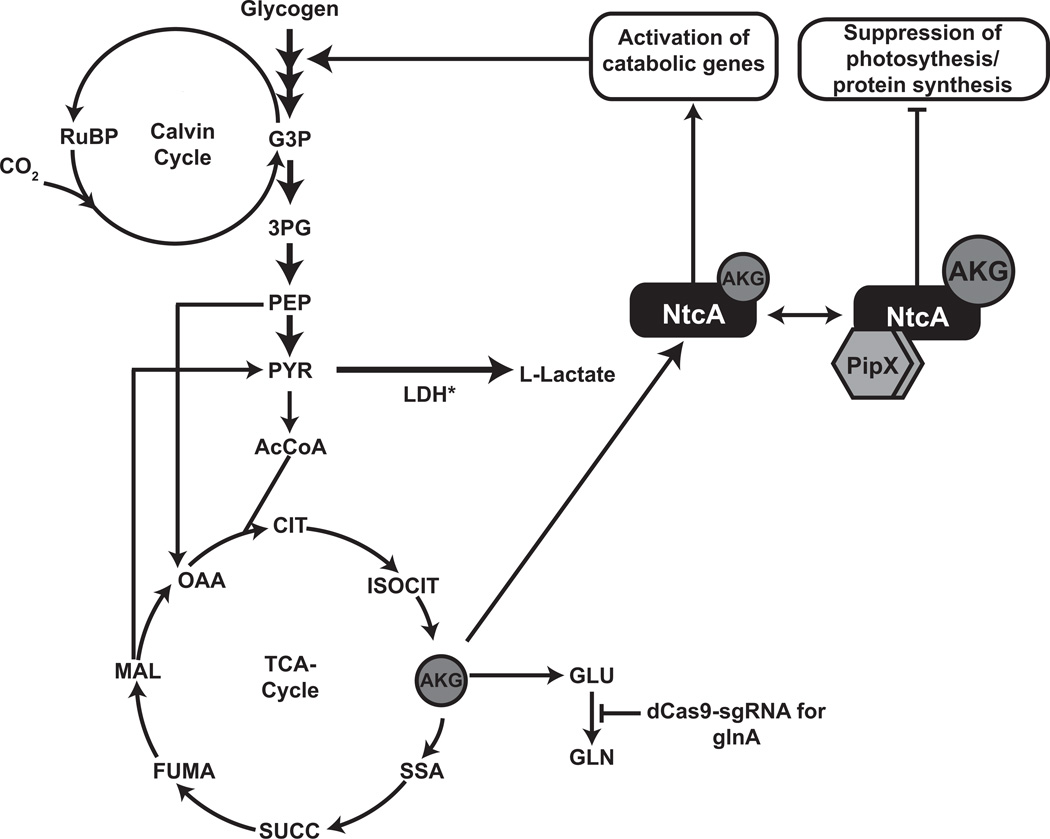

In conjunction with elevated expression of optimized LDH, we predicted that limited flux from carbon fixation to pyruvate would limit lactate production. Enhanced pyruvate excretion and attenuation of phycobilisome and chlorophyll a degradation has been demonstrated under nitrogen starvation in several strains of cyanobacteria when glycogen synthesis is disrupted (Davies et al., 2014, Gründel et al., 2012; Hickman et al., 2013). We hypothesized that moderate reduction of glutamine synthetase I (glnA) expression would slow the rate of nitrogen assimilation through the GS-GOGAT pathway (Muro-Pastor and Florencio, 2003). Slowing the rate of nitrogen assimilation would thereby lead to increased intracellular accumulation of α-ketoglutarate, activating the global nitrogen transcriptional activator, NtcA, a transcription factor from the cyclic AMP receptor protein class (Herrero et al., 2001). This in turn, modulates a suite of metabolic processes related to glycogen degradation and glycolysis, thereby enhancing the flux of fixed carbon to pyruvate (Osanai et al., 2006). However, severe nitrogen limitation will further increase intracellular α-ketoglutarate levels, facilitating complex formation between active NtcA and regulatory factor, PipX (Espinosa et al., 2006), negatively affecting de-novo protein synthesis and overall photosynthesis rates (Espinosa et al., 2014; Krasikov et al., 2012). Therefore, we chose to titrate the degree of repression of glnA using the CRISPRi approached described above (Figure 7). As additional controls, a sgRNA targeting YFP or glnA were integrated in the NS1 locus under the control of the aTc-inducible system, to create strains CC142 and CC130, respectively. dCas9 with the F RBS was integrated in CC130 to create strain CC131.

Figure 7.

Schematic of proposed mechanism for increased lactate production. Moderate accumulation of α-ketoglutarate by glnA repression leads to NtcA activation and subsequent activation of catabolic genes.

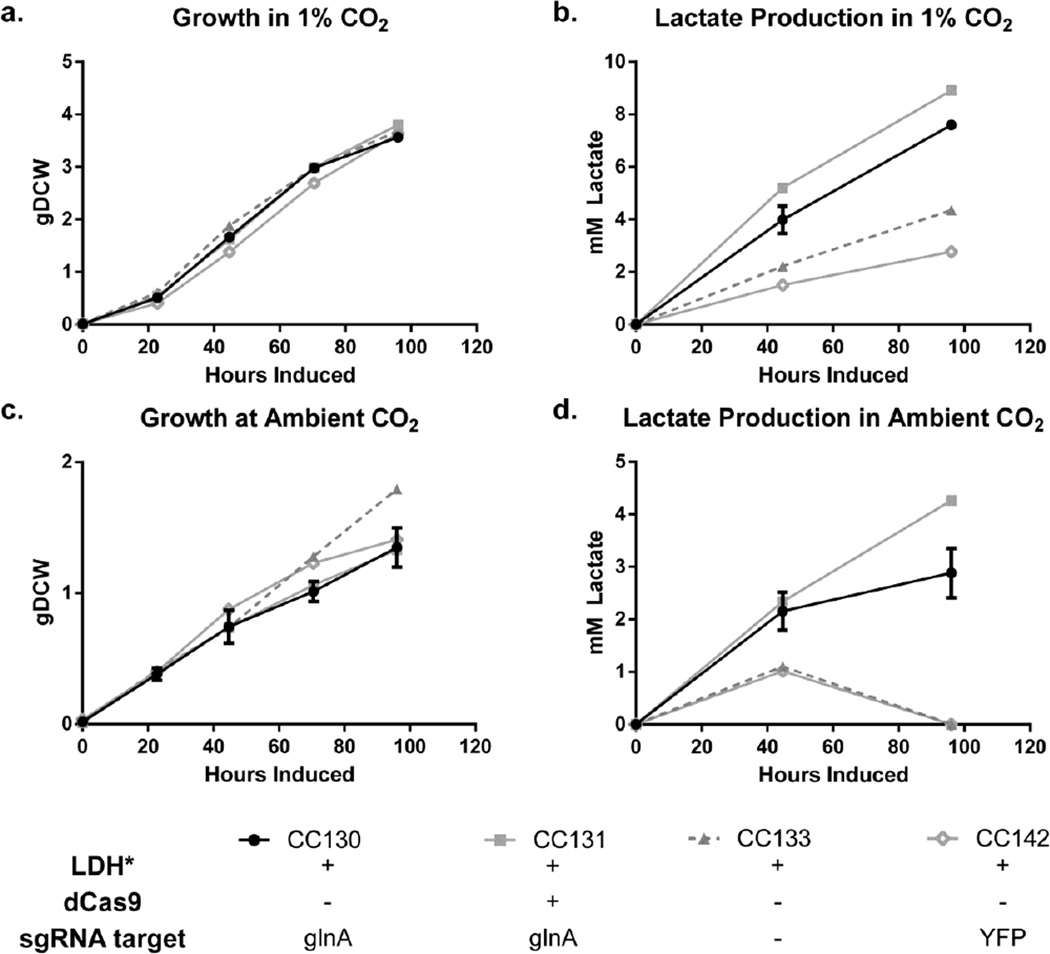

Interestingly, we found enhanced lactate production, as well as delayed phycobilisome and chlorophyll a degradation (Supplemental Figure 6), in both strains harboring the glnA sgRNA when compared to the control strains in 1% CO2 (Figure 8b) or air (Figure 8d). Integration of glnA sgRNA improved production rates from 0.079 ± 0.001 mM/hr in CC130 to 0.092 ± 0.001 mM/hr in CC131, both significantly improved to control strains CC133 and CC142, with rates of 0.045 ± 0.002 mM/hr and 0.029 ± 0.002 mM/hr, respectively, indicating that this effect was glnA sgRNA specific. This glnA sgRNA mediated effect may be due to a basal level of repression through cross-talk with the native CRISPR-Cas systems, unlike the other native genes targeted previously, given the difference in transcript abundance between glnA, ccmK, and cpcB (Ludwig, 2012; Ludwig, 2011). There was no apparent difference in growth rate between the any of the producing strains in 1% CO2 (Figure 8a) or air (Figure 8c). This suggests that glnA repression or LDH expression did not severely impact amino acid synthesis or biomass generation. Given the significant increase in carbon products, the data also suggests that carbon storage polymers were rerouted to product, or carbon fixation rates were enhanced in CC131, analogous to cells engineered to secrete sucrose (Ducat et al., 2012).

Figure 8.

Repression of glutamine synthetase improves lactate production. Growth (a) and (b) lactate production of strains grown in 1% CO2. Growth (c) and (d) lactate production of strains grown in air. Averages of strains grown in duplicate are shown (error bars show standard deviation).

1.4 Conclusions

CRISPRi provides a straightforward method to repress native genes of interest. We showed the functionality of this system genes in the fast-growing cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002 by repressing heterologous YFP and three native genes. We found that leaky expression of the system components was sufficient to achieve strong repression of its target and therefore the system required significant optimization to achieve the desired dynamic range of repression. We found that expression of dCas9 and sgRNA from aTc-inducible promoters allowed for a functional range of repression compared to expressing the sgRNA from constitutive promoters of various strengths. Leakyness of the system was further improved by screening RBS variants to modulate the levels of dCas9. The resulting platform enables the rapid and tritratable repression of gene expression in an industrial relevant cyanobacterium. As a proof of concept, we demonstrated repression of a YFP reporter construct, the native ligh-harvesting phycobilisome (cpcBACDEF), and the carboxysome (ccmK1K2LMN). Repression was titratable and reversible allowing genes to be turned off and on via the addition or removal of aTc.

CRISPRi is a synthetic biology tool that facilitates both the study of natural physiology as well as engineering of strains for applied purposes. Current methods for increasing titers of products include deleting genes in competing pathways, but maximum yields might be achieved by lowering expression to some intermediate level. With CRISPRi technology we can lower expression of essential genes, decrease but not abolish flux towards competing products, and manipulate cellular processes to varying degrees. Here, we improved lactate production from 0.045 ± 0.002 mM lactate/hr to 0.092 ± 0.001 mM lactate/hr by repressing glutamine synthetase, glnA. This was achieved without reducing autotrophic growth rates or mutating chromosomal genes. We anticipate that this approach could be similarly effective in increasing photosynthetic flux to other chemical products, especially those derived from pyruvate.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Reversible and tunable repression of heterologous and natives genes

Repression was optimized by balancing promoter strength and translation levels

Repression of native nitrogen assimilation gene increases lactate production

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Energy through grant DE-SC0010329; the National Science Foundation grant EFRI-1240268; and the William F. Vilas Trust. GCG and TCK are recipients of NIH Biotechnology Training Fellowships (NIGMS - 5 T32 GM08349).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting information is attached and is composed of 6 figures highlighting supplementary aspects of CRISPRi in PCC 7002.

References

- 1.Abràmofff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with Image. J Part II. Biophotonics Int. 2005;11:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alper H, Fischer C, Nevoigt E, Stephanopoulos G. Tuning genetic control through promoter engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:12678–12683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504604102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvey RM, Biswas A, Schluchter WM, Bryant DA. Effects of Modified Phycobilin Biosynthesis in the Cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Strain PCC 7002. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:1663–1671. doi: 10.1128/JB.01392-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begemann MB, Zess EK, Walters EM, Schmitt EF, Markley AL, Pfleger BF. An organic acid based counter selection system for cyanobacteria. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bikard D, Jiang W, Samai P, Hochschild A, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7429–7437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant DA, Zhou J, Gasparich GE, Lorimier D, Guglielmi G, Stirewalt VL. Drews G, et al., editors. 19901990:129–141. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron JC, Wilson SC, Bernstein SL, Kerfeld CA. Biogenesis of a bacterial organelle: the carboxysome assembly pathway. Cell. 2013;155:1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y-J, Liu P, Nielsen AAK, Brophy JAN, Clancy K, Peterson T, Voigt CA. Characterization of 582 natural and synthetic terminators and quantification of their design constraints. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:659–664. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chubukov V, Gerosa L, Kochanowski K, Sauer U. Coordination of microbial metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:327–340. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark RL, Cameron JC, Root TW, Pfleger BF. Insights into the industrial growth of cyanobacteria from a model of the carbon-concentrating mechanism. AIChE J. 2014;60:1269–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleto S, Jensen JV, Wendisch VF, Lu TK. Corynebacterium glutamicum Metabolic Engineering with CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) ACS Synth. Biol. 2016;5:375–385. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copeland MF, Politz MC, Pfleger BF. Application of TALEs, CRISPR/Cas and sRNAs as trans-acting regulators in prokaryotes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014;29:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies FK, Work VH, Beliaev AS, Posewitz MC. Engineering Limonene and Bisabolene Production in Wild Type and a Glycogen-Deficient Mutant of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2014;2:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devroe EJ, Kosuri S, Berry DA, Afeyan NB, Skraly FA, Robertson DE, Green B, Ridley CP. Hyperphotosynthetic organisms. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ducat DC, Avelar-Rivas JA, Way JC, Silver PA. Rerouting carbon flux to enhance photosynthetic productivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:2660–2668. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07901-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espah Borujeni A, Channarasappa AS, Salis HM. Translation rate is controlled by coupled trade-offs between site accessibility, selective RNA unfolding and sliding at upstream standby sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:2646–2659. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espinosa J, Forchhammer K, Burillo S, Contreras A. Interaction network in cyanobacterial nitrogen regulation: PipX, a protein that interacts in a 2-oxoglutarate dependent manner with PII and NtcA. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:457–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espinosa J, Rodríguez-Mateos F, Salinas P, Lanza VF, Dixon R, de la Cruz F, Contreras A. PipX, the coactivator of NtcA, is a global regulator in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E2423–E2430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404097111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farasat I, Kushwaha M, Collens J, Easterbrook M, Guido M, Salis HM. Efficient search, mapping, and optimization of multi-protein genetic systems in diverse bacteria. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014;10:731. doi: 10.15252/msb.20134955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freed EF, Winkler JD, Weiss SJ, Garst AD, Mutalik VK, Arkin AP, Knight R, Gill RT. Genome-Wide Tuning of Protein Expression Levels to Rapidly Engineer Microbial Traits. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman AR, Schaefer MR, Chiang GG, Collier JL. The phycobilisome, a light-harvesting complex responsive to environmental conditions. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:725–749. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.725-749.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gründel M, Scheunemann R, Lockau W, Zilliges Y. Impaired glycogen synthesis causes metabolic overflow reactions and affects stress responses in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Microbiology. 2012;158:3032–3043. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara KY, Araki M, Okai N, Wakai S, Hasunuma T, Kondo A. Development of bio-based fine chemical production through synthetic bioengineering. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014;13:173. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrero A, Muro-Pastor AM, Flores E. Nitrogen control in cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:411–425. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.411-425.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickman JW, Kotovic KM, Miller C, Warrener P, Kaiser B, Jurista T, Budde M, Cross F, Roberts JM, Carleton M. Glycogen synthesis is a required component of the nitrogen stress response in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Algal Res. 2013;2:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keasling JD. Synthetic biology and the development of tools for metabolic engineering. Metab. Eng. 2012;14:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirst H, Formighieri C, Melis A. Maximizing photosynthetic efficiency and culture productivity in cyanobacteria upon minimizing the phycobilisome light-harvesting antenna size. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinstiver BP, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Topkar VV, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, Gonzales APW, Li Z, Peterson RT, Yeh J-RJ, Aryee MJ, Joung JK. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature. 2015;523:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature14592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krasikov V, Aguirre von Wobeser E, Dekker HL, Huisman J, Matthijs HCP. Time-series resolution of gradual nitrogen starvation and its impact on photosynthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Physiol. Plant. 2012;145:426–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Wang X, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2180–2196. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lea-Smith DJ, Bombelli P, Dennis JS, Scott SA, Smith AG, Howe CJ. Phycobilisome-Deficient Strains of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Have Reduced Size and Require Carbon-Limiting Conditions to Exhibit Enhanced Productivity. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:705–714. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.237206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao JC, Mi L, Pontrelli S, Luo S. Fuelling the future: microbial engineering for the production of sustainable biofuels. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, Zhang H, Niedzwiedzki DM, Prado M, He G, Gross ML, Blankenship RE. Phycobilisomes supply excitations to both photosystems in a megacomplex in cyanobacteria. Science. 2013;342:1104–1107. doi: 10.1126/science.1242321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ludwig M, Bryant DA. Acclimation of the Global Transcriptome of the Cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Strain PCC 7002 to Nutrient Limitations and Different Nitrogen Sources. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:145. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludwig M, Bryant DA. Transcription Profiling of the Model Cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Strain PCC 7002 by Next-Gen (SOLiD™) Sequencing of cDNA. Front. Microbiol. 2011;2:41. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludwig M, Sultemeyer D, Price GD. Isolation of ccmKLMN genes from the marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 (Cyanobacteria), and evidence that CcmM is essential for carboxysome assembly. J. Phycol. 2000;36:1109–1118. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch SA, Gill RT. Synthetic biology: New strategies for directing design. Metab. Eng. 2012;14:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, Barrangou R, Brouns SJJ, Charpentier E, Haft DH, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJM, Terns RM, Terns MP, White MF, Yakunin AF, Garrett RA, van der Oost J, Backofen R, Koonin EV. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13:722–736. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markley AL, Begemann MB, Clarke RE, Gordon GC, Pfleger BF. A synthetic biology toolbox for controlling gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015;4:595–603. doi: 10.1021/sb500260k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muro-Pastor MI, Florencio FJ. Regulation of ammonium assimilation in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003;41:595–603. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oliver JWK, Atsumi S. Metabolic design for cyanobacterial chemical synthesis. Photosynth. Res. 2014;120:249–261. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-9997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osanai T, Imamura S, Asayama M, Shirai M, Suzuki I, Murata N, Tanaka K. Nitrogen induction of sugar catabolic gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2006;13:185–195. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsl010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfleger BF, Pitera DJ, Smolke CD, Keasling JD. Combinatorial engineering of intergenic regions in operons tunes expression of multiple genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1027–1032. doi: 10.1038/nbt1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pitera DJ, Paddon CJ, Newman JD, Keasling JD. Balancing a heterologous mevalonate pathway for improved isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2007;9:193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puigbò P, Guzmán E, Romeu A, Garcia-Vallvé S. OPTIMIZER: a web server for optimizing the codon usage of DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W126–W131. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-γuided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reppas NB, Ridley CP. Methods and compositions for the recombinant biosynthesis of n-alkanes. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richter N, Zienert A, Hummel W. A single-point mutation enables lactate dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtilis to utilize NAD+ and NADP+ as cofactor. Eng. Life Sci. 2011;11:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salis HM, Mirsky Ea, Voigt Ca. Automated Design of Synthetic Ribosome Binding Sites to Precisely Control Protein Expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;27:946–950. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smanski MJ, Zhou H, Claesen J, Shen B, Fischbach MA, Voigt CA. Synthetic biology to access and expand nature’s chemical diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:135–149. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanton BC, Nielsen AAK, Tamsir A, Clancy K, Peterson T, Voigt CA. Genomic mining of prokaryotic repressors for orthogonal logic gates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;10:99–105. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stevens SE, Patterson COP, Myers J. THE PRODUCTION OF HYDROGEN PEROXIDE BY BLUE-GREEN ALGAE: A SURVEY. J. Phycol. 1973;9:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu J, Du G, Chen J, Zhou J. Enhancing flavonoid production by systematically tuning the central metabolic pathways based on a CRISPR interference system in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13477. doi: 10.1038/srep13477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu H, Xiao T, Chen C-H, Li W, Meyer CA, Wu Q, Wu D, Cong L, Zhang F, Liu JS, Brown M, Liu XS. Sequence determinants of improved CRISPR sgRNA design. Genome Res. 2015;25:1147–1157. doi: 10.1101/gr.191452.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu P, Li L, Zhang F, Stephanopoulos G, Koffas M. Improving fatty acids production by engineering dynamic pathway regulation and metabolic control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:11299–11304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406401111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yao L, Cengic I, Anfelt J, Hudson EP. Multiple gene repression in cyanobacteria using CRISPRi. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Jessup M. Todd O. Yeates, Cheryl A. Kerfeld, Sabine Heinhorst, Gordon C. Cannon & Jessup M. Shively. Nat. microviol Rev. 2008:681–691. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zess EK, Begemann MB, Pfleger BF. Construction of new synthetic biology tools for the control of gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016;113:424–432. doi: 10.1002/bit.25713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang F, Ouellet M, Batth TS, Adams PD, Petzold CJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD. Enhancing fatty acid production by the expression of the regulatory transcription factor FadR. Metab. Eng. 2012;14:653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.