Abstract

Retinoic acid receptor (RAR) has been implicated in pathological stimuli-induced cardiac remodeling. To determine whether the impairment of RARα signaling directly contributes to the development of heart dysfunction and the involved mechanisms, tamoxifen-induced myocardial specific RARα deletion (RARαKO) mice were utilized. Echocardiographic and cardiac catheterization studies showed significant diastolic dysfunction after 16 wks of gene deletion. However, no significant differences were observed in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), between RARαKO and wild type (WT) control mice. DHE staining showed increased intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in the hearts of RARαKO mice. Significantly increased NOX2 (NADPH oxidase 2) and NOX4 levels and decreased SOD1 and SOD2 levels were observed in RARαKO mouse hearts, which were rescued by overexpression of RARα in cardiomyocytes. Decreased SERCA2a expression and phosphorylation of phospholamban (PLB), along with decreased phosphorylation of Akt and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II δ (CaMKII δ) was observed in RARαKO mouse hearts. Ca2+ reuptake and cardiomyocyte relaxation were delayed by RARα deletion. Overexpression of RARα or inhibition of ROS generation or NOX activation prevented RARα deletion-induced decrease in SERCA2a expression/activation and delayed Ca2+ reuptake. Moreover, the gene and protein expression of RARα was significantly decreased in aged or metabolic stressed mouse hearts. RARα deletion accelerated the development of diastolic dysfunction in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1 diabetic mice or in high fat diet fed mice. In conclusion, myocardial RARα deletion promoted diastolic dysfunction, with a relative preserved LVEF. Increased oxidative stress have an important role in the decreased expression/activation of SERCA2a and Ca2+ mishandling in RARαKO mice, which are major contributing factors in the development of diastolic dysfunction. These data suggest that impairment of cardiac RARα signaling may be a novel mechanism that is directly linked to pathological stimuli-induced diastolic dysfunction.

Keywords: Retinoic acid receptor, diastolic dysfunction, oxidative stress, calcium handling

1. INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality that affects 5.3 million Americans, with increasing prevalence and high hospitalization, but poor diagnostic and treatment options. Evidently, more than 50% of HF patients are diagnosed with diastolic HF, which is prevalent in aging, hypertensive, obese or diabetic patients [1, 2]. Approximately 30–50% of diabetic patients with the typical clinical signs of HF, suffer primarily from diastolic HF [3]. There is no clear guideline-based therapeutic strategy to effectively manage diastolic HF, due to the limited understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms. Oxidative stress have been linked to the development of chronic heart failure and conditions, like hypertension and myocardial infarction, that predispose to HF [4]. Numerous experimental studies have provided direct molecular evidence for an etiological role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in HF [5, 6]. However, clinical trials of antioxidant vitamins have been singularly unsuccessful [7], suggesting that the relationship between oxidative stress and HF or its antecedent conditions is more complex, and understanding the initiation of oxidative stress as well as its downstream effects on cellular function would be significant for identifying the underlying mechanisms of HF and developing more specific targeted therapies.

The nuclear retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and retinoid X receptor (RXR) mediate most of the cellular functions of retinoic acid (RA) [8]. RAR is activated when heterodimerizing with RXRs. We have demonstrated that RARα is one of the receptor subtypes that are abundantly expressed in cardiomyocytes [9, 10]. Activation of RAR/RXR-mediated signaling attenuates hypertrophic stimuli-induced cardiac remodeling, through regulation of oxidative stress/MAP kinase cascades and the renin-angiotensin system [10–15]. Recently, we reported that activation of RARα signaling prevented high glucose and diabetes-induced diastolic dysfunction, through inhibition of intracellular ROS generation and NF-κB signaling-mediated inflammatory responses [9, 16, 17]. These results suggested that RARα-mediated signaling has an important role in regulation of cardiac oxidative stress in response to pathological stimuli, which may serve as a critical mechanism in the development of diastolic dysfunction and HF. Up to date, a majority of studies in relate to the role of RAR/RXR in regulation of adult heart function have utilized RAR pan or subtype selective ligands or antagonists, due to heart malformation and poor survivability of genetic models of RAR deletion. The non-specificity of ligands toward other nuclear receptors results in inaccuracy in interpreting the functional role of RARα in regulation of cellular function in heart. Therefore, studies with inducible receptor knockout models are critical to understand the functional role of RARα in regulation of cardiac oxidative stress and heart function.

Using a mouse model with tamoxifen-induced cardiac specific RARα gene deletion, we investigated the cardiac phenotype, systemic hemodynamics as well as signaling mechanisms in RARαKO mice as compared to WT littermates. We observed that RARαKO mice have an impaired LV diastolic function with preserved EF, which is associated with increased oxidative stress and impaired calcium reuptake and cardiomyocyte relaxation. RARα deletion-induced increase in intracellular ROS has a critical role in the decreased expression/activation of SERCA2a and calcium mishandling. The gene and protein expression of RARα was decreased in aged mouse hearts and metabolic stressed mouse hearts. Gene deletion of RARα promoted the development of diastolic dysfunction at early stage in STZ-induced type 1 diabetic mice and high fat diet fed mice. These data suggest that loss of myocardial RARα signaling is directly associated with the development of diastolic dysfunction, which provide new insights into how cardiac RARα expression/activation impacts heart function and the development of HF.

2. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

A detailed Methods section is available in the Online Data Supplement.

2.1 Experimental model

Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Texas A&M Health Science Center and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Pub. No. 85-23, 1996). Cardiac specific RARα gene deletion (RARαKO) was achieved by tamoxifen injection in male α-MHC-Cre-RARαfl/fl mice at the age of 6 wks (weeks). Age-matched α-MHC-Cre-RARαfl/fl mice treated with vehicle or RARαfl/fl mice, received tamoxifen at same time were used as wild type (WT) control. One set of mice were sacrificed at 20 wks (young group, n=20/group) and another at 64 wks (aged group, n=20/group) after tamoxifen injection. Streptozotocin (STZ) induced type 1 diabetic model was generated by injection of STZ (60 mg/kg/day) intraperitoneally, for 5 days, after 4 wks of tamoxifen injection in RARαKO mice and at age of 10 wks in WT mice (n=12). Mice with fasting blood glucose ≥ 250 mg/dL were used for the study. Mice received buffered saline alone were used as control. Another set of RARαKO and WT mice (n=8) were fed with high fat diet (HFD, 60% of calories from fat; Harlan Teklad, WI) or normal chaw for 12 wks. Gene deletion was induced the same day as initiation of HFD feeding (age of 6 wks).

2.2 Echocardiographic measurements and hemodynamic studies

Echocardiograms were performed using a VisualSonic Vevo 2100 system equipped with a 40-MHz probe, every 4 wks until 64 wks after gene deletion. Mice were anesthetized with 3–5% isoflurane that was reduced to 1.5% to maintain the heart rate between 400–450 beats per minute. The ECG was monitored continuously in real time. The echo-table temperature was controlled at 39°C. The heart was imaged in the 2-dimensional, short-axis and 4 chamber views [18, 19]. Two-dimensional imaging, tissue Doppler and M-Mode measurements were performed to analyze cardiac structural and functional changes. All mice recovered from the procedure without signs of distress. LV catheterization was performed using a 1.2-F microconductance pressure-volume catheter (Transonic Systems Inc, NY) at 20 wks to evaluate LV systolic and diastolic function [19].

2.3 Isolation of neonatal and adult mouse cardiomyocytes

Neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated and cultured from 1–3 day old RARαfl/fl mice, as described previously [20]. RARα gene deletion was induced by transfecting cells with adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Cre recombinase (AdCre, 50 MOI). Cells transfected with AdGFP were used as wild type control. Overexpression of RARα was induced by adenovirus-mediated wild-type RARα (AdRARα) transfection.

Adult mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated from WT and RARαKO mice at 20 wks, as previously described with some modifications [21]. The isolated cardiomyocytes were used immediately for Ca2+ transients and twitch analysis or cultured for other experiments.

2.4 Intracellular Ca2+ transients and twitch analysis

Isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes were loaded with 10 μM/L Fura-2-AM and placed on the stage of an inverted microscope. To evoke electrically stimulated Ca2+ transients and cell contraction, cells were field stimulated at 0.2 Hz until the response reached steady state. Fluorescence measurements were recorded with a dual-excitation fluorescence photomultiplier system (IonOptix, MA). Calcium transients and twitch analysis were assessed using the IonWizard Transient analysis program and video-based edge-detection, respectively. Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ loading capacity was assessed with a brief pulse of caffeine to induce SR Ca2+ release. In some cases, cells were treated with NAC (5 mmol/L, 30 min) before the experiments began. Data were recorded from at least 15 cells per heart and for at least 5 hearts per group.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Student t test, Kruskal–Wallis test, or 1-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey post-hoc test, where appropriate. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Gene deletion of RARα impairs myocardial relaxation and diastolic function

Cardiac specific RARα deletion was achieved by tamoxifen injection, at the age of 6 wks. PCR data showed that gene deletion of RARα occurred only in hearts following tamoxifen injection (Fig. 1A). Cardiac protein expression of RARα was significantly decreased in hearts of RARαKO mice and in cardiomyocytes isolated from RARαKO mice, compared to WT (Fig. 1B and C). The expression of other subtype receptors (RARβ, RXRα and RXRβ) in hearts of RARαKO and WT mice was similar (Supplemental Fig. 1), suggesting that there was no compensatory expression following deletion of RARα. RARα deletion had no effect on mean blood pressure and heart rate (Supplement table 1). Heart function was monitored by echocardiography (monthly for 64 wks) and an invasive hemodynamic assessment (after 20 wks of gene deletion). In RARαKO mice, systolic function was well preserved, as indicated by left ventricular ejection fraction (EF%; 65±2.9 in WT vs 67±1.7 in RARαKO, at 64 wks) and fractional shortening (FS%, 35.9±2.3 in WT vs 36.5±1.3 in RARαKO), which were comparable with WT littermates (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. 2). Hemodynamic studies performed at 20 wks showed similar levels of dP/dtmax, dP/dtmax/EDV and EF% (systolic function indices) in WT and RARαKO mice (Fig. 1G and supplement table 1). Diastolic dysfunction developed after 8–12 wks of gene deletion, with increased isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT) and decreased tissue Doppler early diastolic mitral annular velocity (TDI E′) (Supplemental Fig. 3). RARαKO mice exhibited significant diastolic dysfunction after 16 wks, as evidenced by a decreased E/A ratio, TDI E′ (estimate LV longitudinal myocardial relaxation) and increased IVRT, DT (deceleration time of the E-wave) and E/E′ ratio (estimate left atrial filling pressure), compared to WT mice (Fig. 1E and supplemental Fig. 3). Hemodynamic studies (Fig. 1H–J and supplemental table 1) showed consistent data, with reduced dP/dtmin, decreased dPR ratio (index of heart’s ability to relax to its maximum rate of pressure development) and increased Tau (isovolumic LV relaxation time constant). A mild increase in LVEDP (LV end-diastolic pressure) was observed in RARαKO mice, but did not reach statistical significance, compared to WT. Decreased LV cardiac output (CO) was only observed after 56 wks (Fig. 1F and Supplemental Fig. 3), which is consistent with the increased lung weight in RARαKO mice after 64 wks of gene deletion (Supplemental table 2). These findings suggest that lack of RARα signaling impairs myocardial relaxation, resulting in the development of diastolic dysfunction and HF.

Fig. 1. Cardiac specific gene deletion of RARα induces diastolic dysfunction.

(A) α-MHC-Cre-RARαfl/fl mice were treated with tamoxifen (0.5 mg/day) or vehicle for 4 days, at 6 wks of age, tissues were collected after 2 wks and PCR analysis of genomic DNA performed. Arrow indicates floxed and floxed out band. (B) Protein expression of RARα in hearts of WT and RARαKO mice, after 20 wks of gene deletion, was determined by Western blot and quantified by densitometry. *p<0.05 vs WT. Equal loading was verified by α-tubulin expression. (C) Adult cardiomyocytes were isolated from WT and RARαKO mice after 20 wks, protein expression of RARα determined. (D–F) Echocardiography was performed at the times indicated, before (0) and after gene deletion. (D) LVEF%; (E) E/A ratio and (F) cardiac output (CO). *p<0.05 vs age matched WT. (G–J) Cardiac catheterization was performed, dP/dtmax (G), dP/dtmin (H), LVEDP (I) and Tau (J) analyzed, in WT (n=10) and RARαKO mice (n=9) at 20 wks. *p<0.05 vs WT.

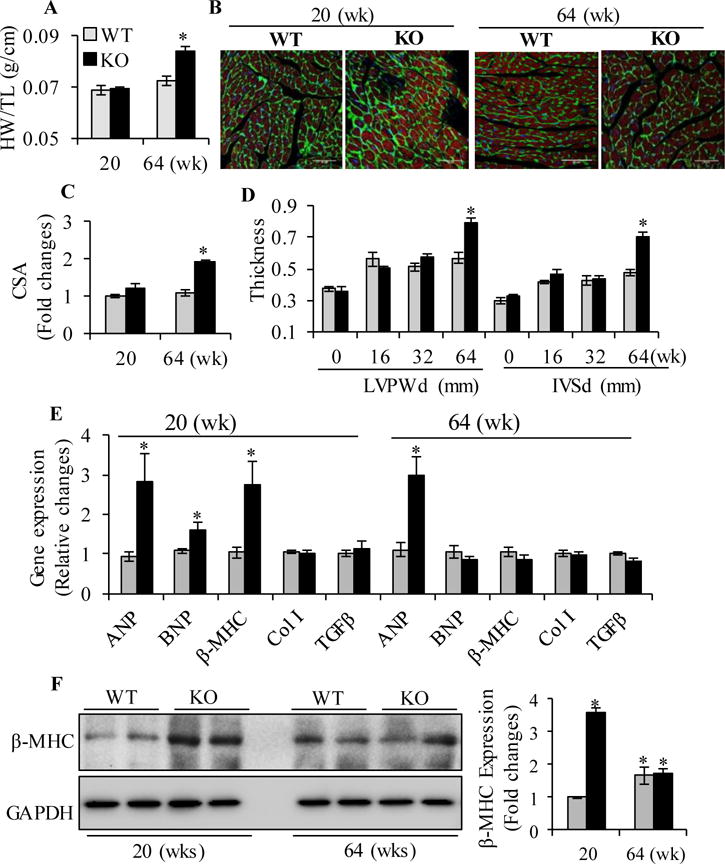

3.2 Role of RARα in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis

The hypertrophic structural changes were only observed in aged RARαKO mice, as evidenced by increased heart weight to tibia length ratio (HW/TL, 0.084±0.002 g/cm versus 0.072±0.002 g/cm in WT, p<0.05), LV/TL ratio (0.067±0.002 g/cm versus 0.053±0.003 g/cm in WT, p<0.05) and cardiomyocyte cross sectional area (CSA, 1.903±0.068 versus 1.083±0.09 in WT, p<0.05) at 64 wks, but not in young (20 wks) mice (Fig. 2A–C, Supplemental table 2). Echocardiographic studies confirmed that significant cardiac hypertrophy developed after 52 wks of gene deletion, by increased thickness of LV posterior wall end diastole (LVPWd, 0.79±0.03 mm versus 0.598±0.03mm in WT, p<0.05) and interventricular septal end diastole (IVSd, 0.67±0.02 mm versus 0.54±0.05 mm in WT, p<0.05), compared to WT mice (Fig. 2D and supplement Fig. 2). LV internal diameter end diastole (LVIDd) and end systole (LVIDs) significantly decreased at 64 wks (LVIDd: 3.43±0.099 mm versus 4.06±0.095 mm in WT; LVIDs: 2.27±0.095 mm versus 2.99±0.091 mm in WT. p<0.05. Supplement Fig. 2), suggesting that RARα deletion induced concentric cardiac hypertrophy in aged mice. Gene expression of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) was significantly increased at 20 wks, however, there were no significant changes in the expression of BNP and β-MHC in aged (64 wks) RARαKO mouse hearts, compared to WT (Fig. 2E). The protein expression of cardiac β-MHC was significantly increased at 20 wks in RARαKO mice, compared to WT (Fig. 2F). Increased protein expression of β-MHC was also observed in aged WT and RARαKO mice (p<0.05, vs young group), however, there was no difference between WT and RARαKO mice (p>0.05). Aging-induced increase in β-MHC expression in WT mice may attenuate the difference between WT and RARαKO mice. Masson’s trichrome staining showed significant increased cardiac fibrosis in aged WT and RARαKO mouse hearts, compared to young mice; however, no significant difference was observed between WT and RARαKO mice (supplemental Fig. 4). Consistent data were observed by hydroxyproline assay. Hydroxyproline serves to stabilize the helical structure of collagen. Hydroxyproline is largely restricted to collagen, the measurement of hydroxyproline levels can be used as an indicator of collagen content. There was no significant increase in LV hydroxyproline levels at 20 wks, in RARαKO mice, compared to WT. However, the hydroxyproline levels markedly increased in aged WT (0.591±0.037 μg/mg LV, vs 0.438±0.013 μg/mg LV, in WT at 20 wks) and RARαKO mice (0.637±0.044 μg/mg LV, vs 0.452±0.070 μg/mg LV, in RARαKO at 20 wks). There was no significant difference between WT and RARαKO mice (supplemental Fig. 4), suggesting that aging is related to the increased collagen content in 64 wks of WT and RARαKO mice. Fibrotic gene expression of collagen type I and TGF-β were similar in young and aged WT and RARαKO mice (Fig. 2E). These data suggest that RARα deletion has no significant effect on cardiac fibrosis.

Fig. 2. Cardiac hypertrophic and fibrotic changes in RARαKO mice.

(A) Heart weight/Tibia length (HW/TL) ratio. (B) Representative images of LV cardiomyocytes stained with wheat germ agglutinin (green), phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 50 μM. (C) Cardiomyocyte CSA was quantified from ~30 cardiomyocytes per section, 6 sections per group. *p<0.05 vs age matched WT. (D) Thickness of the end diastole LV posterior wall (LVPWd) and interventricular septum (IVSd) by echocardiography. *p<0.05 vs age matched WT. (E) Cardiac gene expression of ANP, BNP, β-MHC, Collagen type I (Col I) and TGFβ in WT (n=10) and RARαKO mice (n=10). Data are mean value ± SEM. *p<0.05 vs respective WT group. (F) Protein expression of β-MHC was determined in WT and RARαKO mice (n=6), at 20 and 64 wks, by Western blot and quantified by densitometry. Data are mean value ± SEM. *p<0.05 vs WT at 20 wks.

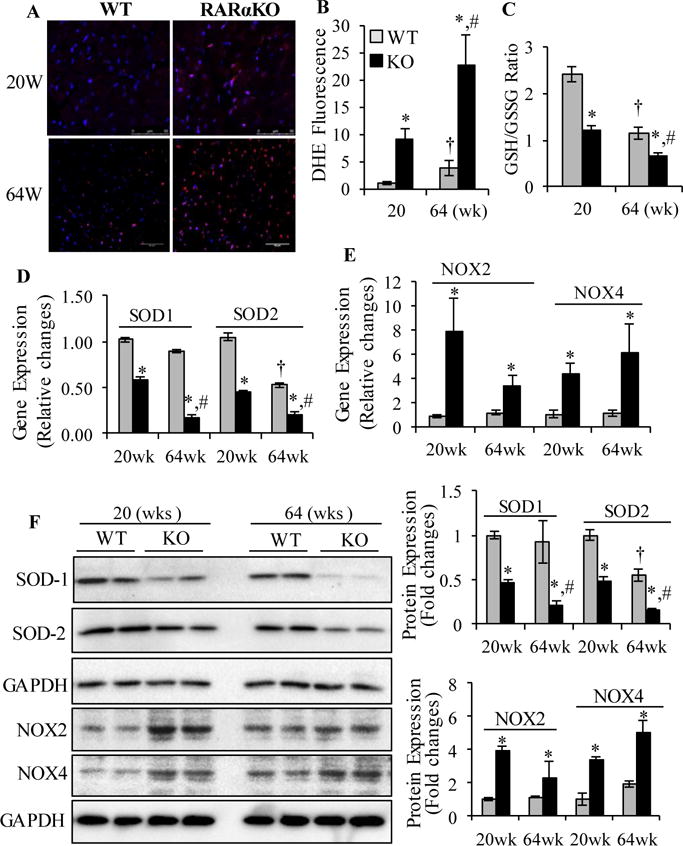

3.3. Gene deletion of RARα promotes cardiac oxidative stress

To determine the role of RARα in regulation of cardiac oxidative stress, dihydroethidium (DHE) staining of LV sections, a relatively specific indicator of O2−, was performed after 20 and 64 wks of gene deletion. A significantly increased DHE staining was observed in RARαKO mouse hearts, at 20 and 64 wks, compared to WT, suggesting that increased intracellular ROS generation following RARα deletion (Fig. 3A and B). RARα gene deletion also promoted aging-induced ROS generation, as evidenced by significantly increased DHE staining in aged RARαKO mouse hearts, compared to young (20 wks) mice. Reduced glutathione (GSH) is a major tissue antioxidant and that GSSG (glutathione disulfide), the oxidized form of glutathione, will accumulate in response to oxidative stress. Thus, the ratio of GSH/GSSG within cells is often used as a measure of cellular oxidative stress. A significantly decreased GSH/GSSG ratio was observed in RARαKO mice, compared to age matched WT (Fig. 3C). Compared to young mice, aged WT and RARαKO mice showed significantly reduced GSH/GSSG ratio (p<0.05), suggesting that increased oxidative stress in aged hearts, and that gene deletion of RARα further promoted aging-induced oxidative stress. Increased ROS in the failing heart are mainly due to impaired antioxidant capacity, such as reduced activity of SOD and catalase, or stimulation of enzymatic sources, in which nonphagocytic NAD(P)H oxidases (NOX) are major enzymes responsible for production of O2−. We then determined the mechanism of RARα deletion-induced ROS generation. Gene and protein expression of NOX2, NOX4, SOD1 and SOD2 was analyzed. Significantly increased gene and protein expression of NOX2 and NOX4 and decreased SOD1 and SOD2 were observed in RARαKO mouse hearts, at 20 and 64 wks, compared to age matched WT (Fig. 3D–F). RARα deletion further reduced gene and protein expression of SOD1 and SOD2 in aged mice, suggesting that RARα deletion had additional deleterious effect on aging-induced impairment of anti-oxidant defense system. A significantly decreased gene and protein expression of SOD2 was also observed in aged WT mice (p<0.05, compared to young WT). In combine with the increased DHE staining and decreased GSH/GSSG ratio in aged WT mice, it is likely that decreased SOD2 has an important role in aging-induced myocardial oxidative stress.

Fig. 3. Gene deletion of RARα promotes cardiac oxidative stress.

(A) Dihydroethidium (DHE) staining (red) of heart sections collected from WT and RARαKO mice. Scale bars: 50 μM. (B) DHE staining intensity was normalized to section area and plotted. (C) GSH/GSSG ratio. *p<0.05 vs age matched WT; †p<0.05 vs 20 wks WT; #p<0.05 vs 20 wks RARαKO. Cardiac gene expression of SOD1, SOD2 (D) and NOX2 and NOX4 (E). Data are mean value ± SEM (n=6). *p<0.05 vs age matched WT. †p<0.05 vs 20 wks WT; #p<0.05 vs 20 wks RARαKO. (F) Protein expression of SOD1, SOD2, NOX2 and NOX4 was determined and quantified by densitometry. *p<0.05 vs age matched WT; †p<0.05 vs 20 wks WT; #p<0.05 vs 20 wks RARαKO.

We further confirmed the role of RARα in regulation of oxidative stress in cultured neonatal and adult mouse cardiomyocytes (Supplemental Fig. 5). Neonatal cardiomyocytes isolated from RARαfl/fl mouse heart were transfected with adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Cre recombinase (AdCre) to induced gene deletion, and then transfected with or without wildtype RARα (AdRARα) to re-expression of RARα. Significantly increased DHE staining was observed in cardiomyocytes with RARα deletion, which was inhibited by overexpression of RARα (supplemental Fig. 5A and B). Adult cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and RARαKO mouse heart at 20 wks showed consistent data. The increased protein expression of NOX2, NOX4 and decreased SOD1 and SOD2 were observed in cardiomyocytes from RARαKO mice, and that overexpression of RARα rescued the decreased SOD1 and SOD2 level and restored the increased NOX2 and NOX4 level to normal (supplemental Fig. 5C and D). These results suggest that lacking of RARα signaling promotes excessive ROS generation, through upregulation of NOX2 and NOX4 and decreasing SOD1 and SOD2-mediated anti-oxidant defense system.

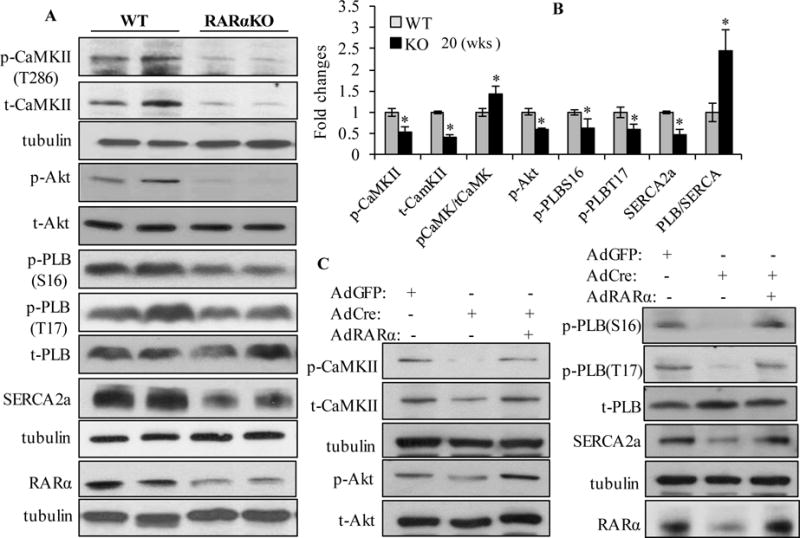

3.4. RARα deletion inhibits the expression/activation of SERCA2a

Diastolic intracellular calcium handling is a major determinant of LV relaxation. Failure to properly recycle Ca2+ through the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) results in severe impairment of myocardial relaxation. It has been reported that sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase2a (SERCA2a) is the main mechanism for removing Ca2+ from cytosol into SR (92% of the calcium in mouse and 75% in human) in cardiomyocytes [22]. SERCA2a activity is tightly regulated by phospholamban (PLB) [23]. PLB reduces the affinity of SERCA2a for Ca2+. This inhibitory effect is released upon phosphorylation at Ser16 by PKA or Thr17 by calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) or Akt [24, 25]. PLB exists as monomeric, dimeric and pentameric forms (~6 to ~30KD) [26, 27]. The monomers represent the active fraction of PLB by attenuating the activity of the Ca2+ pump, and pentamers are involved in modify the phosphorylation status of PLB, function as a regulator of PLB activity [28–30]. We observed decreased protein expression of SERCA2a and phosphorylation of PLB (at both Ser16 and Thr17 sites) in RARαKO mouse hearts, along with unchanged total PLB levels, which resulted in increased PLB/SERCA2a ratio, compared to WT mice, at 20 wks (Fig. 4A and B) and 64 wks (supplemental Fig. 7A). Multiple bands that represent monomeric and pentameric form of PLB were observed with long time exposure (Supplemental Fig. 6). The phosphorylation of PLB at Ser16 (~6, ~14 and ~24 KD) and Thr 17 (~6 and ~14 KD) was detected in the hearts of WT mice, and the monomeric form (~6KD) was abundantly expressed in myocardium. RARα deletion attenuated the phosphorylation of monomeric and pentameric form of PLB. These data suggest that RARα deletion inhibits SERCA2a activity through regulation of the phosphorylation of PLB. The phosphorylation of Akt was decreased in RARαKO mouse hearts. Interestingly, the total protein level of CaMKIIδ significantly decreased following RARα deletion. Though the relative phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ (against total CaMKIIδ) was increased, the overall phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ (against total α-tubulin) was decreased in RARαKO mouse hearts.

Fig. 4. Gene deletion of RARα impairs calcium handling signaling.

(A) Immunoblotting of total and/or phosphorylated CaMKIIδ, Akt, PLB (~6 KD), SERCA2a and RARα in the hearts of WT and RARαKO mice, at 20 wks (n=6). Loading control was determined by α-tubulin expression. (B) Quantitative analysis of the data in (A). *P<0.05 vs WT. (C) Neonatal cardiomyocytes isolated from RARαfl/fl mice were transfected with AdCre for 24 h, then transfected with or without AdRARα. AdGFP transfected cells were used as control. Total and phosphorylated CaMKIIδ, Akt, PLB, SERCA2a and RARα were determined and quantified (Supplemental Fig. 7B).

The effect of RARα deletion on SERCA2a expression/activation was further confirmed in cultured neonatal and adult mouse cardiomyocytes. As shown in Fig. 4C, deletion of RARα resulted in decreased protein expression of SERCA2a and phosphorylation of PLB (Ser16 and Thr17), and increased PLB/SERCA2a ratio, suggesting inhibited SERCA2a activity. Overexpression of RARα prevented the decreased SERCA2a activity (quantification data shown in supplemental Fig. 7B). In consistent with the in vivo data, decreased phosphorylation of Akt and the expression/phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ were observed in cardiomyocytes with RARα deletion, which were rescued by overexpression of RARα (Fig 4C and supplemental Fig. 7B). Adult RARαKO cardiomyocytes were cultured and pretreated with specific activators for PKA (8-Br-cAMP), CaMKII (activated CaMKII) or Akt (SC79). We observed that RARα deletion-induced decrease in the phosphorylation of PLB at Ser16 was restored by 8-Br-cAMP, and the reduced phosphorylation of PLB at Thr17 was restored by activated CaMKII and SC79 (supplemental Fig. 8A). These data suggest that RARα deletion may impair the phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKIIδ or Akt, which results in inhibition of the phosphorylation of PLB, leading to increased PLB/SERCA2a ratio and SERCA2a inactivation.

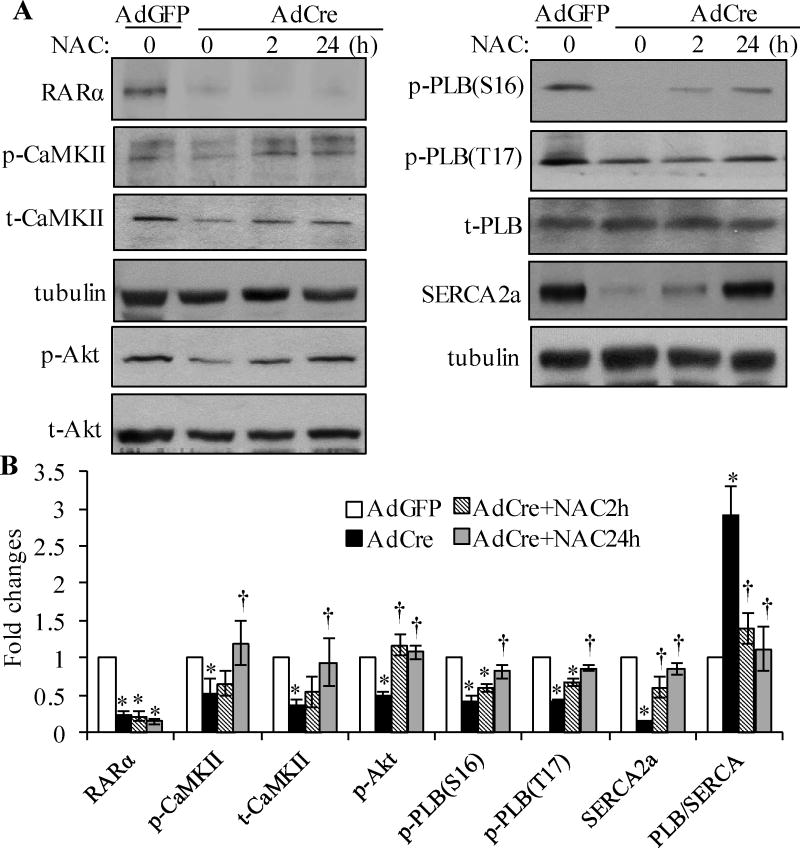

3.5. Oxidative stress is involved in RARα deletion-induced downregulation of SERCA2a and calcium mishandling

Neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes were treated with NAC (N-acetyl-L-cysteine, a ROS scavenger) for 2 and 24 h, after RARα deletion, role of oxidative stress in RARα deletion-induced downregulation/inactivation of SERCA2a was determined. RARα deletion-induced inhibition of the expression of SERCA2a and phosphorylation of PLB (Ser16 and Thr17), CaMKIIδ and Akt were prevented by 24 h of NAC treatment (Fig. 5A and B). Moreover, inhibition of NOX activation by VAS2870 in adult RARαKO cardiomyocytes, also rescued the decreased expression and phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ (Supplemental Fig. 8B). These results suggest that RARα deletion-induced oxidative stress has an important role in the downregulation/inactivation of SERCA2a in cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 5. Oxidative stress is involved in RARα deletion-induced calcium mishandling.

Neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes were transfected with AdGFP or AdCre, and then treated with or without N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC, 5 mmol/L) for 2 and 24 h, protein expression and phosphorylation of Akt, CaMKIIδ, PLB, SERCA2a, RARα and α-tubulin determined by Western blot (A) and quantified (B). *p<0.05 vs AdGFP; †p<0.05 vs AdCre.

We further determined the role of oxidative stress in Ca2+ handling and cell contractility. Adult cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and RARαKO mouse hearts, at 20 wks, were cultured and treated with or without NAC for 30 min, cardiomyocyte contractile activity and Ca2+ cycling determined. As shown in table 1, we observed that myocyte shortening was depressed in RARαKO myocytes, in response to 0.2 Hz stimulation, with a maximal inhibition of 38% in peak shortening and 46% in +dL/dt (maximal velocities of shortening), compared to WT. Cardiomyocyte relengthening (relaxation) was significantly impaired in RARαKO cardiomyocytes, as characterized by slowed −dL/dt (maximum velocity of relengthening), increased TR50, TR90 (time to 50% and 90% of relengthening, respectively) and Tau, suggesting that RARα deletion impairs cardiomyocyte relaxation and cell contractility in response to stress stimulation. RARα deletion had no effect on calcium release, as there were no significant changes in the resting diastolic [Ca2+]I, the peak rate of calcium release (dep v), the time to maximal departure velocity (dep v t) and time to 50% of the peak height in RARαKO cardiomyocytes, compared to WT. SR Ca2+ load was slightly decreased in RARαKO cardiomyocytes, but, didn’t reach statistical significance, compared to WT. Importantly, Ca2+ reuptake was impaired in RARαKO cardiomyocytes, as demonstrated by decreased peak rate of decline of Ca2+ transients (return velocity, ret v), increased time to 50% and 90% of the base line (T50CR and T90CR, respectively) and prolonged tau (calcium transient decay). These data suggest that delayed Ca2+ reuptake is the main mechanism contributing to RARα deletion-induced impairment of relaxation. RARα deletion-induced impairment of calcium reuptake and cell relaxation was significantly improved after NAC treatment. These data suggest that oxidative stress has a major contribution in RARα deletion-induced calcium mishandling and impaired relaxation.

Table 1.

Cell contractility and Ca2+ transients in cardiomyocytes from WT and RARαKO Mice

| WT (n=6) | RARαKO (n=7) | RARαKO+NAC (n=4) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Contractility | |||

| Peak shortening (%) | 5.49±0.31 | 3.37±0.25* | 3.81±0.16 |

| +dL/dt (μm/s) | 162.3±17.7 | 86.5±9.56* | 134.8±10.6† |

| −dL/dt (μm/s) | 104.8±12.2 | 43.2±7.4* | 89.3±13.1† |

| TPS50% (s) | 0.058±0.002 | 0.061±0.002 | 0.059±0.003 |

| TPS90% (s) | 0.096±0.006 | 0.106±0.006 | 0.098±0.006 |

| TR50% (s) | 0.236±0.016 | 0.293±0.018* | 0.2446±0.026† |

| TR90% (s) | 0.411±0.028 | 0.669±0.052* | 0.462±0.033† |

| Tau (s) | 0.135±0.009 | 0.196±0.013* | 0.144±0.023† |

| Ca2+ transients | |||

| Baseline | 1.121±0.019 | 1.145±0.012 | 1.148±0.017 |

| dep v | 2.354±0.174 | 2.422±0.142 | 2.387±0.502 |

| dep v t | 0.024±0.002 | 0.019±0.012 | 0.021±0.002 |

| bl%peak h | 6.538±0.445 | 6.569±0.477 | 6.333±1.095 |

| T50CI (s) | 0.029±0.002 | 0.026±0.001 | 0.027±0.001 |

| T90CI (s) | 0.052±0.002 | 0.048±0.001 | 0.049±0.001 |

| SR load | 0.502±0.041 | 0.449±0.036 | 0.476±0.042 |

| ret v | 0.658±0.060 | 0.397±0.017* | 0.551±0.028† |

| T50CR(s) | 0.249±0.008 | 0.305±0.007* | 0.274±0.007† |

| T90CR (s) | 0.546±0.034 | 0.805±0.052* | 0.627±0.016† |

| Tau (s) | 0.242±0.009 | 0.358±0.014* | 0.291±0.024† |

Adult cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and RARαKO mice after 20 wks of gene deletion, treated with or without NAC for 30 min. Cells were field stimulated, mechanical properties and intracellular Ca2+ transients were measured. NAC: N-acetyl-L-cysteine. For cell contractility: TPS50% and TPS90%: time to 50% and 90% of the peak shortening; TR50% and TR90%: time to 50% or 90% cell relengthening; Tau: the exponential decay time constant of the function. For Ca2+ transients: dep v: maximum velocities of Ca2+ transient ratio increase; T50CI and T90CI: time to 50% or 90% of Ca2+ transient ratio increase; ret v: maximum velocities of Ca2+ transient ratio recovery; T50CR and T90CR: time to 50% or 90% of Ca2+ transient ratio recovery; Tau: single exponential intracellular Ca2+ decay. Data are means ± SEM.

P<0.05 vs WT;

P<0.05 vs RARαKO.

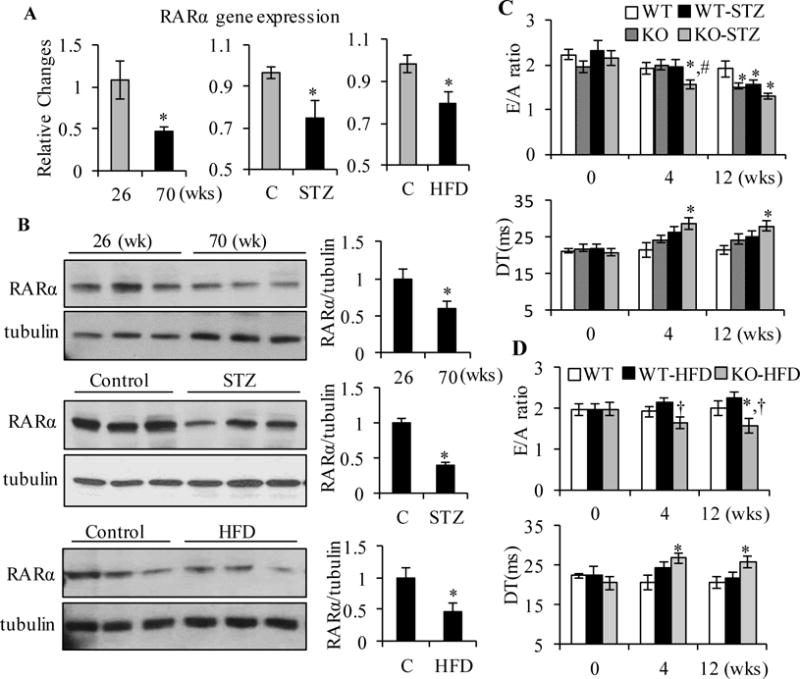

3.6. Cardiac expression of RARα has an important role in aging and metabolic stress-induced diastolic dysfunction and oxidative stress

We have reported that decreased cardiac expression of RARα in ZDF rats, along with diastolic dysfunction and increased oxidative stress, which were ameliorated by RARα selective ligand [17]. Thus, we further analyzed the contribution of RARα in the development of diastolic dysfunction in aging and metabolic disorder mouse models. Hearts were collected from young (age of 26 wks), aged (age of 70 wks), 20 wks of STZ-induced type 1 diabetic or HFD-fed mice, gene and protein expression of RARα was determined. As shown in Fig 6A and B, cardiac gene and protein expression of RARα were significantly decreased in aged, STZ-induced diabetic and HFD-fed hearts. Next, we analyzed heart functional changes in these mouse models. Increased IVRT and decreased TDI E’ were observed in aged mice, compared to young mice, suggesting that diastolic dysfunction developed with aging (supplemental Fig. 3). RARα deletion also promoted the ROS generation in aged mouse hearts (Fig. 3 A–C). Decreased E/A ratio and increased DT were observed in STZ-treated or HFD-fed RARαKO mice, at 4 wks, compared to STZ-treated or HFD-fed WT mice (Fig. 6C and D), suggesting that deletion of RARα accelerated metabolic stress-induced development of diastolic dysfunction.

Fig. 6. Role of RARα in regulation of metabolic stress-induced diastolic dysfunction.

Gene (A) and protein (B) expression of RARα was determined by real-time RT-PCR and Western blot, respectively, in hearts from young (26 wks old) and aged (70 wks old), control, STZ or HFD-fed mice (16 wks). *p<0.05 vs young or control mice. E/A ratio and DT were analyzed by echocardiography in control, STZ-treated (C) or HFD-fed (D) WT and RARαKO mice, at the times indicated. *p<0.05 vs age matched WT, #p<0.05 vs WT-STZ group; †p<0.05 vs WT-HFD group.

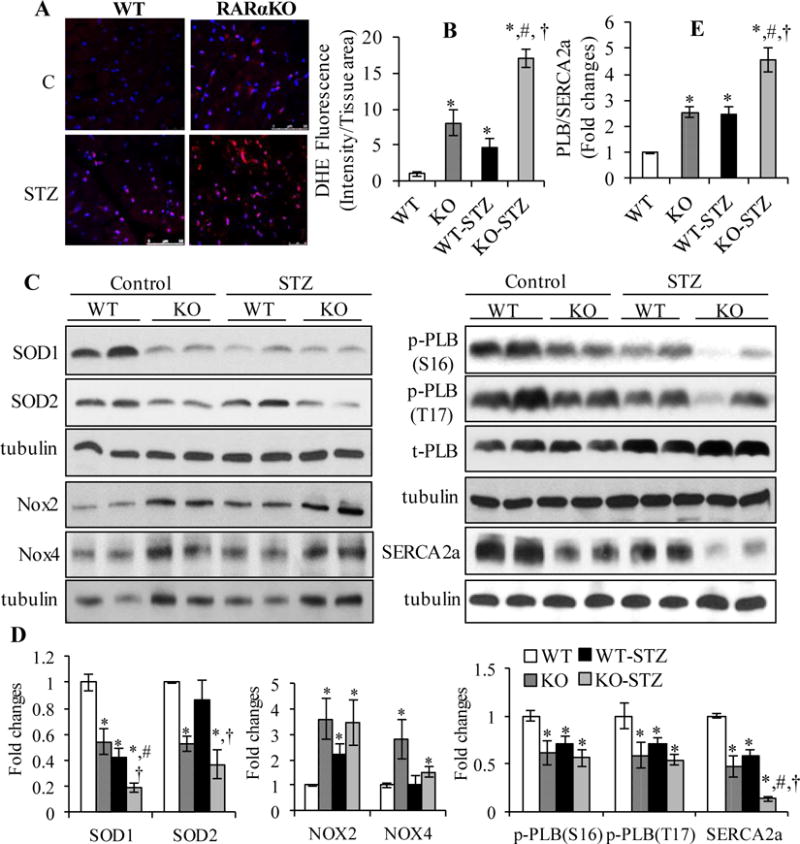

Next, we determined the effect of RARα deletion on cardiac oxidative stress and the expression of SEARCA2a in STZ-induced type 1 diabetic mice. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, DHE staining increased dramatically in STZ-RARαKO mice, compared to STZ-WT and non-diabetic RARαKO mice. RARα deletion induced a significant decrease in SOD1 and SOD2 protein levels and increase in NOX2 and NOX4 expression in both diabetic and non-diabetic mice, compared to WT-STZ mice (Fig. 7C and D). Significantly decreased expression of SERCA2a, phosphorylation of PLB and increased PLB/SERCA2a ratio were observed in STZ-RARαKO mice, compared to STZ-WT or non-diabetic RARαKO mice. These data suggest that downregulated expression and/or activation of RARα is involved in cardiac oxidative stress and calcium mishandling, which has an important role in the early development of diastolic dysfunction in mice with metabolic stress.

Fig. 7. Effect of RARα deletion on cardiac oxidative stress and the expression of SEARCA2a in STZ mice.

(A) DHE staining (red) of heart sections in WT and RARαKO mice, after 16 wks of STZ injection. Scale bar: 50 μM. Staining intensity was normalized to section area and plotted (B). *p<0.05 vs WT; #p<0.05 vs RARαKO; †p<0.05 vs WT-STZ group. (C) LV collected from control and STZ treated WT and RARαKO mice, after 16 wks, protein expression of SOD1, SOD2, Nox2, Nox4, SERCA2a and phosphorylation of PLB was determined by Western blot and quantified by densitometry (D). (E) PLB/SERCA2a ratio. *p<0.05 vs WT; #p<0.05 vs RARαKO; †p<0.05 vs WT-STZ.

4. DISCUSION

This study provides the first evidence that deletion of RARα in adult mouse myocardium causes diastolic dysfunction with a relatively preserved LVEF and that downregulation of cardiac RARα is directly associated with the development of diastolic dysfunction, in aging and metabolic stressed hearts. RARα deletion promotes intracellular ROS generation and oxidative stress, through increasing the expression of NOX2 and NOX4 and inhibiting SOD1 and SOD2 levels; and that increased oxidative stress has a critical role in RARα deletion-induced SEARCA2a inactivation, calcium mishandling and subsequent diastolic dysfunction.

The importance of RAR/RXR signaling pathway has been evidenced by heart malformation and early death in constitutive RARα and RXRα knockout mice [31–33]. The high degree of conservation of RAR and RXR across vertebrates and specific patterns of expression during embryogenesis and in adult tissues, suggest that each of the receptor subtypes performs a specific function [34]. We have demonstrated that activation of RAR by receptor selective ligands inhibits mechanical stretch, angiotensin II, pressure overload or metabolic stress-induced cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and heart dysfunction, in vitro and in vivo [9, 10, 14, 15, 17]. Silencing the expression of RARα in cardiomyocytes promoted cell apoptosis [9]. Importantly, RARα, as one of the major subtype receptors expressed in heart, its expression and transcriptional activation were significantly inhibited in high glucose-stimulated cardiomyocytes and in the hearts of Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats [9, 17, 35]. Moreover, we found that gene and protein expression of RARα was significantly decreased in aged myocardium and in the hearts of STZ-induced type 1 diabetic mice or HFD fed mice, in the present studies. These data strongly suggest that impairment of RARα signaling may be directly associated with the development of heart dysfunction in response to various pathological stimuli. Using an inducible cardiac specific knockout mouse model, we provided the first evidence that loss of RARα-mediated signaling resulted in diastolic dysfunction, with preserved LVEF in adult mice. Echocardiographic and hemodynamic studies demonstrated that cardiac specific deletion of RARα induced decreased E/A ratio, TDI E′, dP/dtmin and increased E/E′, IVRT, DT and Tau, which indicating prolonged LV relaxation and increased left atrial filling pressure. RARα deletion significantly impaired cardiomyocyte relaxation, as evidenced by slowed −dL/dt, increased TR50, TR90 and Tau in adult cardiomyocytes isolated from RARαKO mouse hearts. RARα deletion had no significant effect on LV systolic function, as evidenced by unchanged LVEF%, FS% and dP/dtmax, compared to WT mice, suggesting that impairment of RARα signaling leads to the development of diastolic dysfunction, with preserved systolic function. Though the in vivo functional analysis showed normal systolic function in RARαKO mice, in vitro studies showed that cardiomyocyte contractility was decreased in isolated RARαKO cardiomyocytes, in response to 0.2 Hz electrical stimulation, suggesting that LV systolic function is relatively preserved in RARαKO mice. This is consistent with clinical studies which have shown that the subtle abnormalities in resting systolic performance in patients with diastolic heart failure become more dramatic during physiological stress [36, 37]. The importance of RARα in regulation of heart function was further demonstrated in metabolic stressed mouse models. Gene deletion of RARα accelerated the development of diastolic dysfunction, at early stage (4 wks after gene deletion and challenged with metabolic stress), in STZ-induced type 1 diabetic mice and HFD fed mice, compared to WT mice, where diastolic dysfunction developed around 12–16 wks in response to metabolic stress. In combine with the decreased cardiac gene and protein expression of RARα in STZ or HFD mice, it is clear that downregulation of cardiac RARα signaling is directly linked to the development of diastolic dysfunction and heart failure, in response to pathological stimuli.

Cardiac hypertrophy contributes to the impaired active relaxation, increased passive stiffness of the LV and subsequent diastolic dysfunction and HF [38]. RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction was observed after 8–12 wks of gene deletion, along with increased gene expression of ANP, BAP and β-MHC (markers of cardiac hypertrophy and HF), however, the hypertrophic structural changes were only observed after 52 wks of gene deletion, suggesting that RARα deletion induced early development of diastolic dysfunction in the absence of hypertrophy. This hypertrophy independent diastolic dysfunction has been reported in population-based clinical studies, which have shown that many patients with diastolic HF have either concentric remodeling in the absence of hypertrophy, or even normal LV geometry [39, 40]. Cardiac fibrosis and increased collagen turnover also contribute to the increased myocardial stiffness and diastolic dysfunction [41, 42]. However, the fibrotic gene expression (TGFβ and collagen type I) and collagen levels are comparable in WT and RARαKO mice, suggesting that RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction may be not related to increased myocardial fibrosis. Determining the effect of RARα on collagen cross-linking and turnover (activity of matrix metalloproteases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases) will provide more evidence to clarify the direct linkage between fibrosis and RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction.

Cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBP-C), a cardiac-specific thick filament accessory proteins [43] that can modulate cross-bridge attachment/detachment cycling process by its phosphorylation status, appears to be involved in the diastolic dysfunction associated with diastolic HF. Large amount of animal and human studies have shown the importance of cMyBP-C in regulation of LV relaxation and diastolic function [44–48]. Mutations in cMyBP-C induce diastolic dysfunction in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which is independent of hypertrophy [44, 45]. Loss of cMyBP-C in mice causes diastolic dysfunction [46] and that conditional cMyBP-C knockout induces diastolic dysfunction before the onset of cardiac hypertrophy [47]. RARα deletion induced diastolic dysfunction phenotype is similar with the functional changes demonstrated in cMyBP-C knockout mice. Recent studies further indicated that posttranslational modification of cMyBP-C is directly associated with diastolic dysfunction. Oxidative stress-induced S-glutathionylation of cMyBP-C induces Ca2+ sensitization and a slowing of cross-bridge kinetics, leading to diastolic dysfunction [49, 50]. The phosphorylation of cMyBP-C by PKA and CaMKIIδ [51–53] has been implicated in regulation of diastolic function [19, 54]. Unphosphorylated cMyBP-C appears to repress cross-bridge attachment and detachment, results in impaired relaxation. We observed significantly increased ROS generation and decreased PKA/CaMKIIδ activation in RARαKO mice (as discussed below), thus, the posttranslational modification of cMyBP-C may be involved in RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction, through inhibition of the phosphorylation of cMyBP-C or increasing the S-glutathionylation of cMyBP-C. Further study is required to clarify the role of cMyBP-C in RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction.

It has been reported that decreased SERCA2a function and reduced Ca2+ uptake activity is associated with Ca2+ mishandling and slow relaxation in diastolic dysfunction [55–57]. Decreased Ca2+ reuptake and slowed cardiomyocyte relaxation were observed in adult cardiomyocytes with RARα deletion, in consistent with these observations, downregulated expression of SERCA2a and decreased phosphorylation of PLB were demonstrated in RARαKO mouse hearts or cardiomyocytes with RARα deletion, which were rescued by overexpression of RARα. These data suggest that decreased SR Ca2+ uptake activity due to inhibited SERCA2a function is one of the main mechanisms in RARα deletion-induced impairment of cardiomyocyte relaxation and diastolic dysfunction. RARα deletion inhibited the phosphorylation of PLB, without affecting the total expression level of PLB, which resulted in increased PLB/SERca2a ratio, leading to inhibition of the enzymatic activity of SERCA2a and impaired Ca2+ uptake. We observed that RARα deletion-mediated inhibition of the phosphorylation of PLB was associated with decreased phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ and Akt, and that activation of CaMKII or Akt abolished the inhibitory effect of RARα deletion on PLB phosphorylation at Thr17. Though we did not determined the activation of PKA, RARα deletion-induced decrease in phosphorylation of PLB at Ser16 was rescued by PKA activator. Furthermore, overexpression of RARα prevented RARα deletion-induced inhibition of the phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ, Akt and PLB. These results suggest that RARα signaling has an important role in regulation of PKA, CaMKII or Akt activity, which contribute to RARα deletion-induced inhibition of phosphorylation of PLB and inactivation of SERCA2a. However, the mechanism of RARα signaling in regulation of the activation of PKA, CaMKII or Akt in cardiomyocytes remains unclear.

Interestingly, we observed that the total expression level of CaMKIIδ was significantly decreased following RARα deletion, though the phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ was relatively increased when compared to total CaMKIIδ, the overall phosphorylation of CaMKIIδ was reduced due to the decreased total protein level. These data suggest that decreased expression of CaMKIIδ may have an important role in RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction, likely through the following mechanisms: (1) reducing the phosphorylation of PLB and inhibition of SERCA2a-mediated SR Ca2+ uptake, as we showed that increase in activation of CaMKIIδ restored the decreased PLB phosphorylation level in response to RARα deletion; (2) inhibiting the phosphorylation of titin, which is associated with the increased LV stiffness. Though we did not study the effect of RARα deletion on titin protein, previous studies have shown that inhibition of CaMKIIδ leads to deterioration in diastolic function through regulation of titin phosphorylation [58–60]. Most of studies have suggested that CaMKII-inhibition may be a therapeutic intervention for chronic overload-induced HF [61, 62]. However, our observation suggests that inhibition of CaMKIIδ may be associated with the development of diastolic dysfunction. More studies are necessitated to clarify the role of RARα in regulation of CaMKIIδ and the association with which may provide a novel signaling mechanism for understanding how impaired RARα signaling contributes to diastolic dysfunction and HF.

Oxidative stress plays an important pathogenic role in experimental and human heart failure. Increased ROS in the failing myocardium are mainly due to impaired antioxidant capacity, such as reduced activity of SOD and catalase, or stimulation of enzymatic sources, in which nonphagocytic NAD(P)H oxidases (NOX) are major enzymes responsible for production of O2−. NOX2 and NOX4 are the predominant isoforms expressed in cardiomyocytes [63]. Studies have shown that NOX2 activation contributes to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis and heart failure through promoting oxidative stress and activation of MAP kinase pathway [64]. Evidence for a role of NOX4 in cardiac remodeling is contradictory, with considerable debate on whether NOX4 is protective or deleterious during cardiac response to injury [65, 66]. RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction is associated with significantly increased oxidative stress. Given the decreased SOD1 and SOD2 levels and increased expression of NOX2 and NOX4, the increased production of ROS in cardiomyocytes with RARα deletion is due to both impaired antioxidant ability to quench excess ROS, and NOX2/NOX4-mediated intracellular including mitochondria overproduction of ROS. Overexpression of RARα in cardiomyocytes inhibited RARα-deletion-induced increase in ROS generation, through inhibiting the expression of NOX2 and NOX4 and upregulating SOD1 and SOD2 levels, suggesting that impairment of RARα signaling significantly contributes to the increased oxidative stress in myocardium. Redox-mediated activation of the MAP kinase pathways, mitochondrial death pathway and impaired SR calcium handling have been implicated in heart failure [67]. Oxidative stress may contribute to diastolic dysfunction by modification of RyRs, resulting in diastolic SR Ca2+ leaks and relaxation stiffness of cardiomyocytes [68]. The oxidation of CaMKII in response to ROS regulates relaxation through SERCA2a and activates the cell death pathway in cardiomyocytes [69, 70]. Redox-mediated SERCA2a sulfonation, on the cysteine residue, contributes to the impaired cardiomyocyte relaxation [71]. ROS-mediated inhibition of PKA activity may also have an important role in calcium mishandling [72]. RARα deletion-induced impairment of Ca2+ uptake, decreased expression/activation of SERCA2a and the phosphorylation of PLB, CaMKIIδ and Akt were rescued by anti-oxidant treatment or inhibition of NOX activation, suggesting that RARα deletion-induced oxidative stress have a major role in calcium mishandling, through regulation of the activation of PKA, CaMKIIδ or Akt, directly or indirectly, leading to dephosphorylation of PLB and inactivation of SERCA2a, which ultimately leads to impaired cardiomyocyte relaxation and diastolic dysfunction.

Systemic and myocardial (especially coronary microvascular endothelial) inflammation has been demonstrated to be an important pathophysiological mechanism for diastolic dysfunction in diastolic HF patients [73, 74]. Myocardial inflammation promotes oxidative stress in coronary microvascular endothelial cells, which limits NO bioavailability for adjacent cardiomyocytes. Impaired NO bioavailability suppresses cGMP-PKG-mediated signaling, which augments cardiomyocyte stiffness through hypophosphorylation of titin, resulting in diastolic dysfunction [75]. We observed increased oxidative stress in hearts of RARαKO mice, and that RARα deletion further promoted ROS generation in diabetic myocardium in STZ mice, which is associated with early development of diastolic dysfunction. We have previously reported that activation of RAR/RXR signaling inhibits metabolic stress-induced inflammatory responses and oxidative stress, through regulation of NF-κB signaling [16, 17], suggesting that RAR/RXR-mediated inhibitory effect on myocardial inflammation and oxidative stress is involved in regulation of diastolic function. Though we did not directly identify the inflammatory responses following RARα deletion in the present study, significantly increased ROS generation in RARαKO or diabetic RARαKO mice indirectly suggest the possible involvement of myocardial inflammation in the development of diastolic dysfunction. Further studies are necessary to understand the role of oxidative stress in regulation of NO/PKG signaling and titin expression/phosphorylation, and the association with RARα deletion-induced diastolic dysfunction.

In conclusion, we have shown that myocardium specific deletion of RARα in adult mouse results in diastolic dysfunction with preserved LVEF, and that downregulation of cardiac RARα has a critical role in the development of diastolic dysfunction, in response to aging and metabolic stress. RARα deletion-induced oxidative stress contribute significantly to decreased expression/activation of SERCA2a and Ca2+ mishandling, which is directly associated with the impaired LV relaxation and diastolic dysfunction. Our findings highlight a novel mechanism that links nuclear RAR/RXR signaling to diastolic dysfunction, this will provide the impetus for generating effective therapeutic approaches to target RARα-mediated signaling for the prevention and treatment of HF patients.

Supplementary Material

Highlight.

Cardiac specific gene deletion of RARα induces diastolic dysfunction with preserved LVEF

Loss of RARα signaling promotes cardiac oxidative stress and calcium mishandling

Oxidative stress plays a key role in SERCA2a inactivation and calcium mishandling in RARαKO mice

Cardiac expression of RARα is downregulated in mice with metabolic stress or aging

RARα deletion accelerates metabolic stress-induced diastolic dysfunction

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System, Temple, Texas.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the NIH (1R01 HL091902).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None declared

References

- 1.Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation. 2012;126:65–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.080770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyer JK, Thanigaraj S, Schechtman KB, Perez JE. Prevalence of ventricular diastolic dysfunction in asymptomatic, normotensive patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:870–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munzel T, Gori T, Keaney JF, Jr, Maack C, Daiber A. Pathophysiological role of oxidative stress in systolic and diastolic heart failure and its therapeutic implications. European heart journal. 2015;36:2555–64. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2181–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ide T, Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Suematsu N, Hayashidani S, Ichikawa K, et al. Direct evidence for increased hydroxyl radicals originating from superoxide in the failing myocardium. Circ Res. 2000;86:152–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myung SK, Ju W, Cho B, Oh SW, Park SM, Koo BK, et al. Efficacy of vitamin and antioxidant supplements in prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013;346:f10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. Faseb J. 1996;10:940–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guleria RS, Choudhary R, Tanaka T, Baker KM, Pan J. Retinoic acid receptor-mediated signaling protects cardiomyocytes from hyperglycemia induced apoptosis: role of the renin-angiotensin system. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1292–307. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palm-Leis A, Singh US, Herbelin BS, Olsovsky GD, Baker KM, Pan J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases mediate the inhibitory effects of all-trans retinoic acid on the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54905–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou MD, Sucov HM, Evans RM, Chien KR. Retinoid-dependent pathways suppress myocardial cell hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7391–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Garami M, Cheng T, Gardner DG. 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3, and retinoic acid antagonize endothelin-stimulated hypertrophy of neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1577–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI118582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang HJ, Zhu YC, Yao T. Effects of all-trans retinoic acid on angiotensin II-induced myocyte hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2162–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01192.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhary R, Baker KM, Pan J. All-trans retinoic acid prevents angiotensin II- and mechanical stretch-induced reactive oxygen species generation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:172–81. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choudhary R, Palm-Leis A, Scott RC, 3rd, Guleria RS, Rachut E, Baker KM, et al. All-trans retinoic acid prevents development of cardiac remodeling in aortic banded rats by inhibiting the renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H633–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01301.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nizamutdinova IT, Guleria RS, Singh AB, Kendall JA, Jr, Baker KM, Pan J. Retinoic acid protects cardiomyocytes from high glucose-induced apoptosis via inhibition of sustained activation of NF-kappaB signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:380–92. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guleria RS, Singh AB, Nizamutdinova IT, Souslova T, Mohammad AA, Kendall JA, Jr, et al. Activation of retinoid receptor-mediated signaling ameliorates diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in Zucker diabetic rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;57C:106–18. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas CM, Yong QC, Seqqat R, Chandel N, Feldman DL, Baker KM, et al. Direct renin inhibition prevents cardiac dysfunction in a diabetic mouse model: comparison with an angiotensin receptor antagonist and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:529–41. doi: 10.1042/CS20120448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosas PC, Liu Y, Abdalla MI, Thomas CM, Kidwell DT, Dusio GF, et al. Phosphorylation of cardiac Myosin-binding protein-C is a critical mediator of diastolic function. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:582–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sreejit P, Kumar S, Verma RS. An improved protocol for primary culture of cardiomyocyte from neonatal mice. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2008;44:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s11626-007-9079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connell TD, Rodrigo MC, Simpson PC. Isolation and culture of adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Methods in molecular biology. 2007;357:271–96. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-214-9:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bers DM. Calcium fluxes involved in control of cardiac myocyte contraction. Circ Res. 2000;87:275–81. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stammers AN, Susser SE, Hamm NC, Hlynsky MW, Kimber DE, Kehler DS, et al. The regulation of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium-ATPases (SERCA) Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;93:843–54. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haghighi K, Bidwell P, Kranias EG. Phospholamban interactome in cardiac contractility and survival: A new vision of an old friend. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;77:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catalucci D, Latronico MV, Ceci M, Rusconi F, Young HS, Gallo P, et al. Akt increases sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ cycling by direct phosphorylation of phospholamban at Thr17. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28180–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmerman HK, Collins JH, Theibert JL, Wegener AD, Jones LR. Sequence analysis of phospholamban. Identification of phosphorylation sites and two major structural domains. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13333–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tada M, Toyofuku T. Molecular regulation of phospholamban function and expression. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 1998;8:330–40. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(98)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittmann T, Lohse MJ, Schmitt JP. Phospholamban pentamers attenuate PKA-dependent phosphorylation of monomers. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;80:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akin BL, Hurley TD, Chen Z, Jones LR. The structural basis for phospholamban inhibition of the calcium pump in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:30181–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.501585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toyoshima C, Asahi M, Sugita Y, Khanna R, Tsuda T, MacLennan DH. Modeling of the inhibitory interaction of phospholamban with the Ca2+ ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:467–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237326100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kastner P, Grondona JM, Mark M, Gansmuller A, LeMeur M, Decimo D, et al. Genetic analysis of RXR alpha developmental function: convergence of RXR and RAR signaling pathways in heart and eye morphogenesis. Cell. 1994;78:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruber PJ, Kubalak SW, Pexieder T, Sucov HM, Evans RM, Chien KR. RXR alpha deficiency confers genetic susceptibility for aortic sac, conotruncal, atrioventricular cushion, and ventricular muscle defects in mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1332–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI118920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee RY, Luo J, Evans RM, Giguere V, Sucov HM. Compartment-selective sensitivity of cardiovascular morphogenesis to combinations of retinoic acid receptor gene mutations. Circ Res. 1997;80:757–64. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leid M, Kastner P, Chambon P. Multiplicity generates diversity in the retinoic acid signalling pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:427–33. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90014-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh AB, Guleria RS, Nizamutdinova IT, Baker KM, Pan J. High Glucose-induced repression of RAR/RXR in cardiomyocytes is mediated through oxidative stress/JNK signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2632–44. doi: 10.1002/jcp.23005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraigher-Krainer E, Shah AM, Gupta DK, Santos A, Claggett B, Pieske B, et al. Impaired systolic function by strain imaging in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:447–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phan TT, Abozguia K, Nallur Shivu G, Mahadevan G, Ahmed I, Williams L, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is characterized by dynamic impairment of active relaxation and contraction of the left ventricle on exercise and associated with myocardial energy deficiency. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:402–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kass DA, Bronzwaer JG, Paulus WJ. What mechanisms underlie diastolic dysfunction in heart failure? Circ Res. 2004;94:1533–42. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129254.25507.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zile MR, Gottdiener JS, Hetzel SJ, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, et al. Prevalence and significance of alterations in cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2011;124:2491–501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.011031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borlaug BA, Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Redfield MM. Contractility and ventricular systolic stiffening in hypertensive heart disease insights into the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su MY, Lin LY, Tseng YH, Chang CC, Wu CK, Lin JL, et al. CMR-verified diffuse myocardial fibrosis is associated with diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:991–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasner M, Westermann D, Lopez B, Gaub R, Escher F, Kuhl U, et al. Diastolic tissue Doppler indexes correlate with the degree of collagen expression and cross-linking in heart failure and normal ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:977–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Previs MJ, Beck Previs S, Gulick J, Robbins J, Warshaw DM. Molecular mechanics of cardiac myosin-binding protein C in native thick filaments. Science. 2012;337:1215–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1223602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagueh SF, Bachinski LL, Meyer D, Hill R, Zoghbi WA, Tam JW, et al. Tissue Doppler imaging consistently detects myocardial abnormalities in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and provides a novel means for an early diagnosis before and independently of hypertrophy. Circulation. 2001;104:128–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poutanen T, Tikanoja T, Jaaskelainen P, Jokinen E, Silvast A, Laakso M, et al. Diastolic dysfunction without left ventricular hypertrophy is an early finding in children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-causing mutations in the beta-myosin heavy chain, alpha-tropomyosin, and myosin-binding protein C genes. Am Heart J. 2006;151:725 e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris SP, Bartley CR, Hacker TA, McDonald KS, Douglas PS, Greaser ML, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cardiac myosin binding protein-C knockout mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012222.70819.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen PP, Patel JR, Powers PA, Fitzsimons DP, Moss RL. Dissociation of structural and functional phenotypes in cardiac myosin-binding protein C conditional knockout mice. Circulation. 2012;126:1194–205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fraysse B, Weinberger F, Bardswell SC, Cuello F, Vignier N, Geertz B, et al. Increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and diastolic dysfunction as early consequences of Mybpc3 mutation in heterozygous knock-in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilder T, Ryba DM, Wieczorek DF, Wolska BM, Solaro RJ. N-acetylcysteine reverses diastolic dysfunction and hypertrophy in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1720–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00339.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Figueiredo-Freitas C, Dulce RA, Foster MW, Liang J, Yamashita AM, Lima-Rosa FL, et al. S-Nitrosylation of Sarcomeric Proteins Depresses Myofilament Ca2+) Sensitivity in Intact Cardiomyocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;23:1017–34. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jia W, Shaffer JF, Harris SP, Leary JA. Identification of novel protein kinase A phosphorylation sites in the M-domain of human and murine cardiac myosin binding protein-C using mass spectrometry analysis. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1843–53. doi: 10.1021/pr901006h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sadayappan S, Gulick J, Osinska H, Barefield D, Cuello F, Avkiran M, et al. A critical function for Ser-282 in cardiac Myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation and cardiac function. Circ Res. 2011;109:141–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.242560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlender KK, Bean LJ. Phosphorylation of chicken cardiac C-protein by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2811–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tong CW, Stelzer JE, Greaser ML, Powers PA, Moss RL. Acceleration of crossbridge kinetics by protein kinase A phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein C modulates cardiac function. Circ Res. 2008;103:974–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt U, Hajjar RJ, Helm PA, Kim CS, Doye AA, Gwathmey JK. Contribution of abnormal sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase activity to systolic and diastolic dysfunction in human heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1929–37. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kranias EG, Hajjar RJ. Modulation of cardiac contractility by the phospholamban/SERCA2a regulatome. Circ Res. 2012;110:1646–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.259754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wold LE, Dutta K, Mason MM, Ren J, Cala SE, Schwanke ML, et al. Impaired SERCA function contributes to cardiomyocyte dysfunction in insulin resistant rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng J, Xu L, Lai D, Guilbert A, Lim HJ, Keskanokwong T, et al. CaMKII inhibition in heart failure, beneficial, harmful, or both. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1454–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00812.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neef S, Sag CM, Daut M, Baumer H, Grefe C, El-Armouche A, et al. While systolic cardiomyocyte function is preserved, diastolic myocyte function and recovery from acidosis are impaired in CaMKIIdelta-KO mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;59:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamdani N, Krysiak J, Kreusser MM, Neef S, Dos Remedios CG, Maier LS, et al. Crucial role for Ca2(+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II in regulating diastolic stress of normal and failing hearts via titin phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2013;112:664–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang T, Maier LS, Dalton ND, Miyamoto S, Ross J, Jr, Bers DM, et al. The deltaC isoform of CaMKII is activated in cardiac hypertrophy and induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ Res. 2003;92:912–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069686.31472.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling H, Zhang T, Pereira L, Means CK, Cheng H, Gu Y, et al. Requirement for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II in the transition from pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1230–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI38022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang M, Perino A, Ghigo A, Hirsch E, Shah AM. NADPH oxidases in heart failure: poachers or gamekeepers? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1024–41. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parajuli N, Patel VB, Wang W, Basu R, Oudit GY. Loss of NOX2 (gp91phox) prevents oxidative stress and progression to advanced heart failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014;127:331–40. doi: 10.1042/CS20130787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao QD, Viswanadhapalli S, Williams P, Shi Q, Tan C, Yi X, et al. NADPH oxidase 4 induces cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy through activating Akt/mTOR and NFkappaB signaling pathways. Circulation. 2015;131:643–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang M, Brewer AC, Schroder K, Santos CX, Grieve DJ, Wang M, et al. NADPH oxidase-4 mediates protection against chronic load-induced stress in mouse hearts by enhancing angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18121–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009700107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sorescu D, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, and NAD(P)H oxidases in the development and progression of heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2002;8:132–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2002.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Terentyev D, Gyorke I, Belevych AE, Terentyeva R, Sridhar A, Nishijima Y, et al. Redox modification of ryanodine receptors contributes to sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in chronic heart failure. Circ Res. 2008;103:1466–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, et al. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palomeque J, Rueda OV, Sapia L, Valverde CA, Salas M, Petroff MV, et al. Angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress resets the Ca2+ dependence of Ca2+-calmodulin protein kinase II and promotes a death pathway conserved across different species. Circ Res. 2009;105:1204–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.204172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qin F, Siwik DA, Lancel S, Zhang J, Kuster GM, Luptak I, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated SERCA cysteine 674 oxidation contributes to impaired cardiac myocyte relaxation in senescent mouse heart. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e000184. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okatan EN, Tuncay E, Turan B. Cardioprotective effect of selenium via modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor calcium release channels in diabetic rat cardiomyocytes through thioredoxin system. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:2110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paulus WJ, Tschope C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Franssen C, Chen S, Unger A, Korkmaz HI, De Keulenaer GW, Tschope C, et al. Myocardial Microvascular Inflammatory Endothelial Activation in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4:312–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kruger M, Kotter S, Grutzner A, Lang P, Andresen C, Redfield MM, et al. Protein kinase G modulates human myocardial passive stiffness by phosphorylation of the titin springs. Circ Res. 2009;104:87–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.