Abstract

Purpose

To develop a new faster and higher quality 3D gagCEST MRI technique for reliable quantification of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) present in the human knee cartilages.

Methods

A new magnetization-prepared 3D Gradient Echo-based MRI pulse sequence has been designed to obtain the B0 inhomogeneity, B1 inhomogeneity, and CEST Z-spectra images.

Results

The gagCEST values of different compartments of knee cartilage are calculated using a newly developed technique for healthy subjects and a symptomatic knee cartilage degenerated subject. The effect of the acquired CEST saturation frequency offset step-size was investigated to establish the optimal step-size to obtain reproducible gagCEST maps. Our novel 3D gagCEST technique demonstrates markedly higher gagCEST contrast value than the previously reported 3D gagCEST studies. This study demonstrates the need for separate B0 and B1 inhomogeneity estimation and correction.

Conclusions

The new technique provided high quality gagCEST maps with clearer visualization of different layers of knee cartilage with reproducible results.

Keywords: 3DgagCEST, magnetization preparation 3D, B1 calibration, B0

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA), one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal conditions, affects a large number of people around the world, with an increasing number of people who are at risk of developing the condition in the future [1]. Progressive and irreversible degradation of joint cartilage is the hallmark feature of OA. Cartilage extracellular components such as glycosaminoglycan (GAG) and collagen are mainly responsible for its bio-mechanical properties [2, 3] and the progressive loss of these components leads to the degeneration of the knee joint and eventually OA. X-ray radiography is the commonly used method in clinical practice to determine the degeneration of knee cartilage, which is highly insensitive to the progression of cartilage loss, hence not appropriate to measure the effectiveness of therapeutic response. MR relaxation-based techniques such as T2, T2*, T1ρ mapping etc., have been used to measure the biochemical composition of the cartilage with varying degrees of success [4–10]. The introduction of high-field MRI scanners has led to the development of new, non-invasive molecular imaging techniques that enable capturing of molecular changes in the cartilage tissue. These developments have great potential in improving diagnosis and monitoring the efficacy of disease-modifying therapies for OA [5]. GAG Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (gagCEST) MRI is a promising technique to non-invasively quantify GAG content present in the cartilage [6]. Both single-slice 2D [11] as well as multi-slice 3D gagCEST MRI [12, 13] methods have been developed for use at 3T and 7T. A recently published 3D gagCEST technique seems to provide lower CEST asymmetry contrast at a frequency offset of 1 p.p.m from bulk water (3% [12, 13]) than the previous 2D gagCEST study in healthy volunteers (6% [11]).

In this study, a new 3D gagCEST MRI technique has been developed to quantify GAG in knee cartilage in clinically acceptable scan times with markedly higher quality than the previous reported 3D gagCEST study [12]. Additionally, the need for separate B0 and B1 inhomogeneity estimation and correction is established. The gagCEST values of cartilage of different compartments of knee are calculated and the reproducibility of the gagCEST scans using the newly developed technique is shown for both asymptomatic and symptomatic subjects.

METHODS

3D Magnetization prepared pulse sequence

In the new magnetization-prepared 3D sequence, a long delay is set between two magnetization preparation pulses (> 3xT1). To optimize the scan time, we use low flip angle segmented gradient echo (GRE) segmented readout with elliptically centered ordering for slice encoding (kz) and phase encoding (ky). The basic looping structure of the sequence and a schematic of the elliptical centric ordering are shown in Fig. 1. For CEST, a frequency-selective saturation pulse train of 5 Hanning windowed pulses with a duration of 99.8 ms, separated by 0.2 ms and B1rms of 2.2 μT is used. For B0 mapping with Water Saturation Shift Referencing (WASSR) [14], a frequency-selective saturation pulse train of 2 Hanning windowed saturation pulses with a B1rms of 0.3 μT is used. For B1 map generation hard pulses with two predefined flip angles (30° and 60°) are used for magnetization preparation. We acquire the entire 3D image for each preparation pulse in 2 shots with a large number (>500) of segments per shot and a shot TR (time between two preparation pulses) of 8000 ms and a segment TR in the range of 6–8 ms. The combined use of elliptical centric ordering and GRAPPA [15] acceleration factor of 2 along the phase encoding direction is expected to provide optimal magnetization prepared contrast in a reasonable scan time.

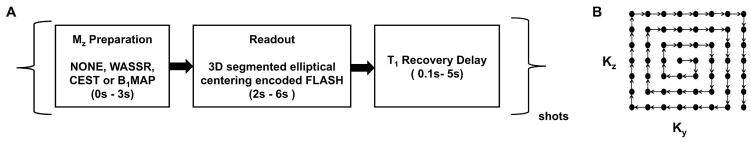

Fig. 1.

A. Block diagram of the 3D gagCEST sequence showing magnetization preparation block, acquisition block and T1 recovery block. B. Schematic displaying elliptically centered ordering for combined phase encoding and slice encoding. The actual encoding order is determined by ordering the points in Ky – Kz space based on scaled Euclidean distance from the center.

Human Studies

All the human scans were performed under an approved Institutional Review Board protocol of the University of Pennsylvania with written informed consent obtained from each volunteer after explaining the study protocol. MRI scans were performed on 5 healthy male subjects of age 20–35 years and one elderly symptomatic male subject of age 65 years old. Out of 6 subjects, 4 subjects including the symptomatic subject were scanned twice, in order to estimate the reproducibility of the results. All MR imaging studies were performed in a Siemens 7T whole body MRI scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) using a circularly polarized (CP) transmit / 28-channel receive array knee coil (inner diameter = 15.4 cm to 18 cm, Quality Electrodynamics, Mayfield Village, OH).

Acquisition Protocol

The scanning protocol consisted of the following steps: (i) a three plane localizer, (ii) axial proton density weighted anatomical scan acquired at 1 mm3 isotropic resolution; the high-resolution anatomical images acquired in axial orientation are reconstructed to coronal and sagittal orientations, and used as localizers for subsequent scans, (iii) localized shimming and reference voltage calculation (~5min), (iv) reference 3D image acquisition without any preparation pulse (16sec), (v) Water saturation shift reference (WASSR) acquisition (~5min), (vi) B1map acquisition (<2min), and (vii) GagCEST image acquisitions (~11min). Step (iii) to (vii) are preformed both in axial and coronal orientations. Total time of all acquisitions were kept under 1 hr.

Localized Shimming and Reference Voltage Calculation

A large rectangular voxel was placed over the entire patellar cartilage for axial orientation, and the femoral and tibial cartilages for the coronal orientation and manual shimming was performed to obtain water line width at half max of about ~0.15 p.p.m. After shimming, two single-voxel spectroscopy data were collected with Stimulated Echo Acquisition Mode (STEAM) sequence with reference voltages of 100V and 200V, respectively [16]. Assuming the peak amplitudes of the spectroscopy water signal to be S1 and S2, optimal reference voltage ‘V’ for the cartilage was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

Reference Image Acquisition

A 3D image acquisition scan was performed with the following spatial encoding parameters: slice thickness = 3 mm, number of slices = 16, flip angle = 5°, shot TR = 8000 ms, TR/TE = 7.7/3.1 ms, FOV = 140×140×48 mm3,, acquisition matrix size = 234*234*16, GRAPPA factor = 2, shots = 2 and “elliptical scanning” option which reduces the number of kz-ky lines acquired to 1634 for both axial and coronal orientations. With these parameters the number of segments per shot is 817 and there is a T1 recovery time of 1.5 s available at the end of the last acquisition segment.

WASSR B0 Map

For WASSR image acquisition, a 200 ms saturation pulse duration with B1rms of 0.3 μT and Δωrange of −0.8 p.p.m to +0.8 p.p.m, with a step size of 0.1 p.p.m was used. Spatial encoding parameters were set identical to the reference image acquisitions for both axial and coronal orientations.

Relative B1 Map (B1rel)

B1rel maps were obtained using the 3D gagCEST sequence with a hard pulse followed by gradient spoiling preparation with identical spatial encoding parameters as the reference image acquisitions in both axial and coronal orientations. For each slice orientation, two images were generated using square preparation pulses with flip angles of 30° and 60° and the following equation was solved in order to obtain flip angle map,

| (2) |

θ(x,y,z) is obtained from the following formula,

| (3) |

Where I (2θ) and I (θ) corresponds to voxel intensity with a preparation flip angle of 60° and 30° respectively, x, y and z are spatial co-ordinates.

GagCEST

For gagCEST acquisition, saturation frequency offsets in the range of −2 p.p.m to +2 p.p.m, with a step size 0.1 p.p.m was used with 500 ms saturation pulse duration with a B1rms of 2.2 μT and identical spatial encoding parameters as the reference image acquisitions in both axial and coronal orientations. Our choice of shot TR of 8000 ms was based on optimization of scan time and gagCEST contrast with one of our subjects.

Post-processing Methods

All image processing and data analysis were performed using in-house developed MATLAB (Mathworks, version R2014a) programs.

Motion Correction

All WASSR, B1, and CEST volumes were registered to the reference volume using a modified affine transformation based motion correction algorithm available in SPM8 (Statistical parametric Mapping software, Version 8) before further processing. Cartilages were manually segmented and analyzed for signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and to overlay cartilage CEST maps on anatomical images.

B0 estimation and correction

The detailed technique of WASSR-based, voxel-wise B0 estimation and correction is described elsewhere [14]. We also estimated the B0 map using the interpolated CEST Z-spectra for comparison purposes.

CEST contrast calculation and B1 correction

The gagCEST contrast was calculated on a voxel-by-voxel basis from the B0 corrected images corresponding to +1 p.p.m and −1 p.p.m. Both M0 (gagCESTM0) and Mz- (gagCESTMz-) based normalization were used while calculating gagCEST values for comparison purposes using the following formulas,

| (4) |

| (5) |

In order to evaluate the effect of the sampling step size of the acquired gagCEST weighted images, gagCEST values were computed with 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 p.p.m saturation offset step sizes by manually under sampling the acquired dataset.

Reproducibility analysis

To estimate the reproducibility of the technique, subjects’ knees were manually positioned approximately in the same location of the coil as in the first scan using foam pads. First, the cartilages (Patellar cartilage in axial slices, femoral and tibial cartilages in coronal slices) were manually segmented from the center 6 slices of the acquired volume. The segmented cartilage section in 3D is further divided into two equal halves (~750 to 1500 voxels) each into medial and lateral segments, and mean gagCEST values were obtained. Inter-class correlation (ICC) with 95% confidence interval was computed for test-retest reliability experiment using SPSS (Version 22) software. ICC value of 0.01–0.20 is interpreted as minimal agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicates fair agreement, an ICC of 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, an ICC of 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement and an ICC>0.81 is considered as perfect agreement [17]. ICC with p value less than 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

A sample stack of reference anatomical knee images in axial and coronal orientations acquired using no preparation pulse is shown in Fig. 2. In all the datasets acquired, both axial and coronal orientations, basic acquisition parameters are optimized such that SNR of cartilages in the reference images was >90.

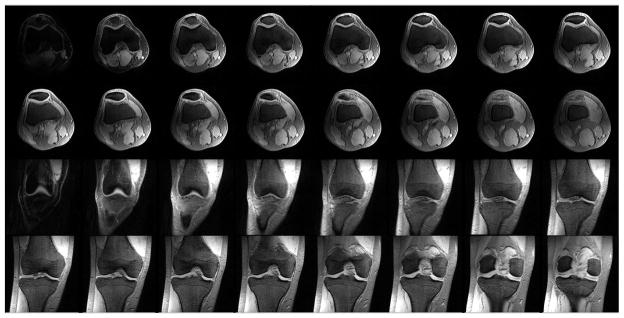

Fig. 2.

Sample stack of anatomical images in axial orientation shows patellar cartilage, coronal orientation shows femoral and tibial cartilages acquired using 3D sequence with no magnetization preparation. SNR on cartilage ROIs were >90 in all the datasets acquired.

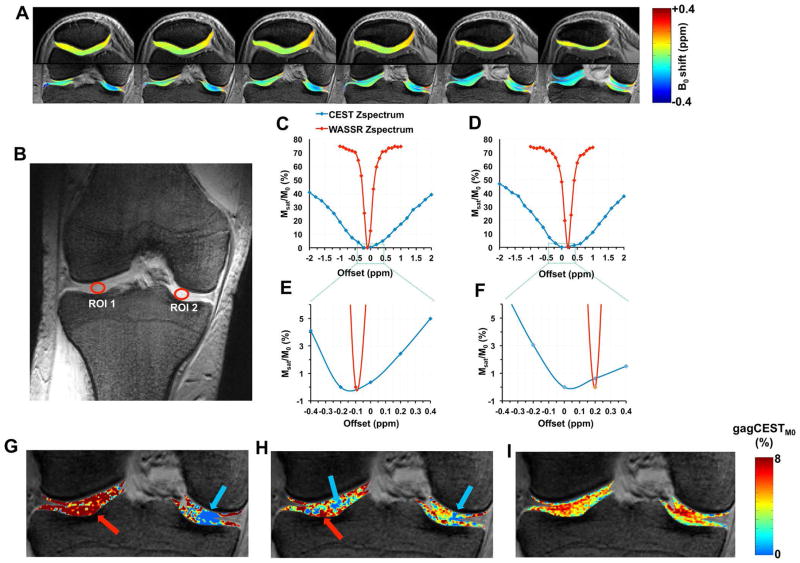

Fig. 3A shows WASSR-based B0 map calculated on the patellar, femoral and tibial cartilages. Due to the localized shimming, in all the 6 subjects scanned, the B0 inhomogeneity values on the cartilage region of interests (ROIs) were well within ± 0.4 p.p.m range. Due to the broad line width of the CEST Z-spectra and the asymmetric nature of the curve, the position of minimum intensity of the interpolated CEST Z-spectrum does not always represent the true B0 inhomogeneity and in turn, the B0 corrected Z-spectrum leads to erroneous CEST contrast calculation. Figs. 3G–I shows the gagCEST without B0 inhomogeneity correction, with correction based on the minima of CEST Z-spectra, and B0 inhomogeneity correction based on WASSR technique, respectively. The gagCEST map generated based on WASSR technique showed more uniform distribution without any negative pixels in the cartilage ROIs. In this study, therefore, we have used WASSR technique for B0 estimation and correction.

Fig. 3.

A. Sample slices of B0 map overlaid on the anatomical images calculated using WASSR technique. B. PD weighted coronal slice shows weight bearing Femoral and Tibial cartilages with the ROIs chosen for analyzing the Z-spectrum. C&D. Line graph shows Z-spectrum of CEST and WASSR intensities after RF saturation at ROI 1 and ROI 2, respectively. E&F. Zoomed version of Z-spectra in C&D (green box). There are differences in the positions of minima between WASSR Z-spectra and CEST Z-spectra. CEST Z-spectra exhibit broad line widths and are inherently asymmetric. G. gagCEST map calculated without correcting for B0 inhomogeneity. H. gagCEST map calculated after B0 inhomogeneity correction using the interpolated Z-spectra itself. I. gagCEST map calculated after B0 inhomogeneity correction using the WASSR technique. Note that the blue arrow points the regions with underestimated or negative CEST values, and red arrow points the regions with overestimated CEST values.

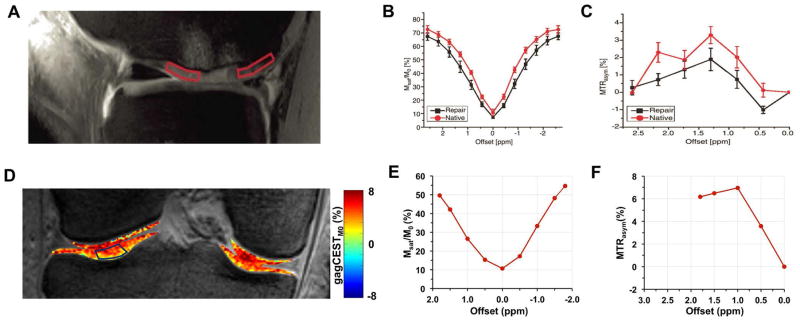

The higher gagCEST contrast value of this 3D acquisition over the previously reported 3D method is illustrated in Fig. 4. For the ROIs chosen from the healthy regions, CEST asymmetry at 1 p.p.m from the previously published method is ~3% while that from the current study is ~7% which is comparable to the results reported from the 2D gagCEST study (11). We ascribe this sensitivity difference mainly to the reduction in the steady state water magnetization available for chemical exchange due to two factors: (i) the time interval between saturation pulses is very short (<1s) and (ii) at end of segmented GRE acquisition train, there is a large decrease of Mz magnetization due to the short TR readout train. This is based on our experimental observations (not shown) regarding the effect of T1 recovery delay in our method.

Fig. 4.

A. Anatomical PD weighted image with ROIs (boxes in native (left) and repair tissue (right)). B. Graph shows the Z-spectra and C. shows the asymmetry analysis of the values obtained from ROIs in A (obtained with permission from Ref [12]). D. gagCEST map acquired using burst mode sequence with E. Z-spectra and F. asymmetry analysis of the data collected from the ROI shown in D (At 1 p.p.m, the calculated asymmetry values of voxels in the ROI are in the range of 3.2 to 11%). Note that the burst mode sequence produces more than double the sensitivity of the previously developed steady-state sequence at 1 p.p.m offset from water resonance.

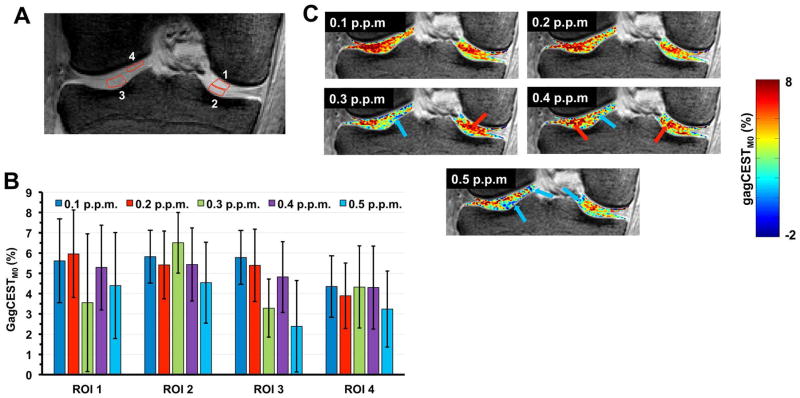

Fig. 5 shows the sensitivity of the saturation offset step size of the acquired CEST Z-spectra calculated gagCEST asymmetry. Step sizes of 0.1 p.p.m and 0.2 p.p.m provide similar results. As the sampling step size increases, the polynomial interpolation used in the B0 correction step seems to be affected leading to erroneous CEST values with more voxels with either negative or overestimated CEST values.

Fig. 5.

A. Anatomical image showing the location of 4 ROI’s chosen for gagCEST analysis. B. Bar plots represents the effect of calculated gagCEST asymmetry on the acquisition coarse sampling step size on the ROIs shown in A. As the step size increases, the asymmetry is affected by B0 correction which leads to voxels with negative (indicated by blue arrows) and exaggerated gagCEST values (indicated by red values) which are shown in gagCEST maps calculated with the step sizes viz., 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 p.p.m in C.

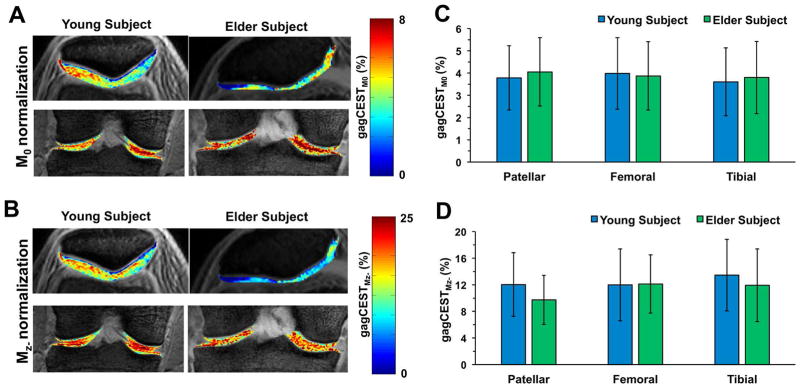

The effect of M0 and Mz- normalizations on calculated gagCEST maps are reported in Fig. 6. The elderly subject’s patellar cartilage is visually found to be thinner than the younger subject’s cartilage. The mean CEST contrast values from the entire cartilage region for both normalizations are shown in Figs. 6C and 6D. Mz- normalization showa a larger dynamic range (~9% to ~16%) than the M0 normalization (3.7% to 4.3%). Also, Mz- normalization shows better discrimination between the patellar cartilage of the healthy young subject and the elderly subject (mean gagCEST values, 12.75 ± 4.7% and 9.48 ± 3.7%).

Fig. 6.

Effect of Normalization Strategy: (A & B) Final CEST maps of patellar and femoral-tibial cartilages from a young healthy subject as well as an elderly subject with knee pain normalized with M0 and Mz-. (C & D) Bar plots represent gagCEST asymmetry from cartilages.

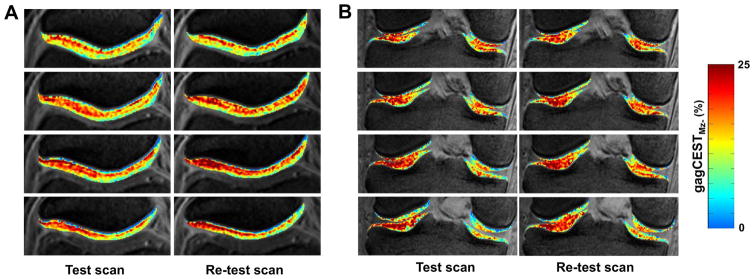

The final gagCEST maps calculated after motion correction, B0, and B1 correction and Mz- normalization are shown in Fig. 7. The interlayer difference in GAG concentration in the maps is clearly evident.

Fig. 7.

A. Representative axial slices showing Mz- normalized gagCEST maps of a healthy subject’s Patellar cartilage showing layer wise differences in the gagCEST values. B. Representative coronal slices showing gagCEST maps of Femoral and Tibial cartilage. Note that the maps are overlaid on the corresponding anatomical images and cropped to show cartilages alone.

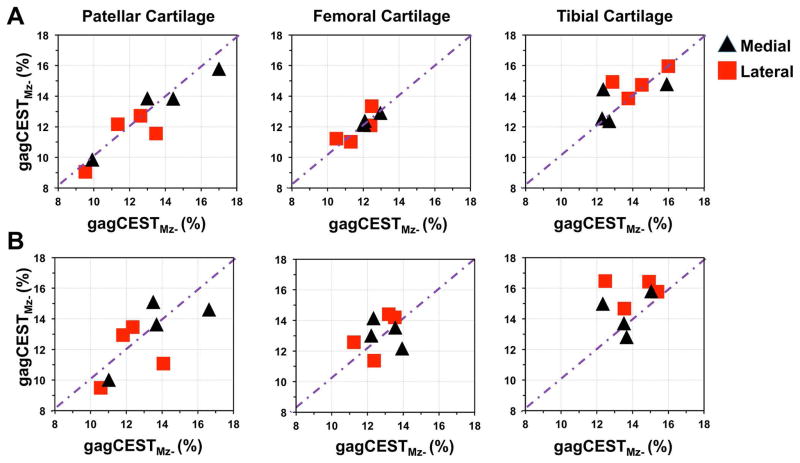

The scatter plot in Fig. 8, shows reproducibility of gagCEST values calculated using Mz- normalization in test-retest experiment in cartilages of different compartments of knee. With the small number of subjects studied, the reproducibility with a saturation offset step size of 0.1 p.p.m was found to be higher with almost all cartilage segment results falling close to the “y=x” line (Fig. 8A). With a saturation offset step size of 0.2 p.p.m, few cartilage segments showed poor reproducibility (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Scatter plots of test-retest data of gagCEST % calculated from cartilages of different compartments of knee of 3 young healthy subjects and 1 elderly subject with knee pain with saturation frequency offset step size of A. 0.1 p.p.m and B. 0.2 p.p.m. Note that most of the points lie on y=x line except few outliers.

We have provided quantitative measures of reproducibility with analysis of interclass-coefficients (ICC) of all cartilage segments in Table 1. With 0.1 p.p.m saturation offset step size, ICC values from all cartlage segments were in the range of 0.8–0.97 with p-values <0.05 (“perfect agreement”) while with 0.2 p.p.m saturation offset step size, ICC values from some cartilage segments were in the range of 0.3–0.4 (“fair agreement”).

Table 1.

Inter-class coefficients of test-retest data with 95% confidence interval mentioned within brackets.

| Patellar Cartilage | Femoral Cartilage | Tibial Cartilage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 p.p.m sampling step-size | 0.957 (0.804, 0.991)* | 0.854 (0.259, 0.971)* | 0.803 (0.113, 0.960)* |

| 0.2 p.p.m sampling step-size | 0.814 (0.093, 0.963)* | 0.398 (−2.062, 0.880) | 0.300 (−0.722, 0.824) |

Note that * denotes statistical significance at p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we report a new 3D gagCEST technique for mapping GAG in the knee cartilages in a practically achievable scan times at 7T with more than twice the gagCEST contrast than the previously reported 3D gagCEST study [12]. The long repetition time between saturation pulses and elliptical-centric ordered segmented gradient echo (GRE) readout seem to maintain high gagCEST contrast. Repetition time between saturation pulses used in this study (8s) leads to ~5% decrease in available water magnetization for subsequent acquisitions, while use of very short repetition times between saturation pulses can lead to >50% decrease in available water magnetization for subsequent acquisitions (based on simulation results). This may be one of the reasons that lead to the lower gagCEST contrast in the previously reported study [12].

Accurate B0 inhomogeneity estimation is crucial to obtain reliable CEST maps. In the present study, the CEST Z-spectra is inherently too broad and asymmetric, leading to a requirement for a robust B0 correction method to greatly improve the accuracy of the asymmetry analysis. We have chosen to use WASSR acquisition for this purpose.

Mz- normalization is known to generally provide a higher dynamic range for CEST contrast by reducing the impact of direct saturation. This seems to be true for 3D gagCEST as well. In this limited study, Mz- normalization shows better discrimination between healthy subjects and one symptomatic subject. A thorough investigation with additional scans may shed light on this effect.

The impact of the step size of saturation offset has been investigated. The test-retest reproducibility (Fig. 8 and Table 1) with a saturation offset step size of 0.1 p.p.m produced excellent agreement (ICC > 0.8, p < 0.05). Sampling step sizes > 0.3 p.p.m provides unreliable results with more voxels with either negative or overestimated CEST contrast. We believe that this is due to the sensitivity of B0 correction. With a saturation offset step size of 0.1 p.p.m, the overall scan time for both the orientations with this technique is under 1 hour. Hence, we believe that this technique is practical for translation to a clinical setting.

In conclusion, the new 3D magnetization prepared 3D technique with long repetition times between preparation pulses along with separate B0 and B1 inhomogeneity estimation and correction, yields reliable and reproducible high-quality gagCEST maps with clear visualization of knee cartilage layers.

Acknowledgments

This project was performed at NIH-NIBIB supported Biomedical Technology Research Center P41 EB015893.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the Unites States: Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saarakkala S, Julkunen P, Kiviranta P, Mäkitalo J, Jurvelin JS, Korhonen RK. Depth-wise progression of osteoarthritis in human articular cartilage: investigation of composition, structure and biomechanics. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2010;18:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas CM, Fuller CJ, Whittles CE, Sharif M. Chondrocyte death by apoptosis is associated with cartilage matrix degradation. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2007;15:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David-Vaudey E, Ghosh S, Ries M, Majumdar S. T2 relaxation time measurements in osteoarthritis. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:673–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mlynárik V, Trattnig S, Huber M, Zembsch A, Imhof H. The role of relaxation times in monitoring proteoglycan depletion in articular cartilage. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:497–502. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199910)10:4<497::aid-jmri1>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosher TJ, Dardzinski BJ, Smith MB. Human articular cartilage: influence of aging and early symptomatic degeneration on the spatial variation of T2--preliminary findings at 3 T. Radiology. 2000;214:259–66. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja15259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regatte RR, Akella SV, Borthakur A, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. In vivo proton MR three-dimensional T1rho mapping of human articular cartilage: initial experience. Radiology. 2003;229:269–74. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291021041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bittersohl B, Hosalkar HS, Hughes T, Kim YJ, Werlen S, Siebenrock KA, Mamisch TC. Feasibility of T2* mapping for the evaluation of hip joint cartilage at 1. 5T using a three-dimensional (3D), gradient-echo (GRE) sequence: a prospective study. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:896–901. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun HJ, Dragoo JL, Hargreaves BA, Levenston ME, Gold GE. Application of advanced magnetic resonance imaging techniques in evaluation of the lower extremity. Radiol Clin North Am. 2013;51:529–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2266–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh A, Haris M, Cai K, Kassey VB, Kogan F, Reddy D, Hariharan H, Reddy R. Chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging of human knee cartilage at 3 T and 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:588–94. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitt B, Zbýn S, Stelzeneder D, Jellus V, Paul D, Lauer L, Bachert P, Trattnig S. Cartilage quality assessment by using glycosaminoglycan chemical exchange saturation transfer and (23)Na MR imaging at 7 T. Radiology. 2011;260:257–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krusche-Mandl I, Schmitt B, Zak L, Apprich S, Aldrian S, Juras V, Friedrich KM, Marlovits S, Weber M, Trattnig S. Long-term results 8 years after autologous osteochondral transplantation: 7 T gagCEST and sodium magnetic resonance imaging with morphological and clinical correlation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1441–50. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202–10. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh A, Haris M, Cai K, Kogan F, Hariharan H, Reddy R. High resolution T1ρ mapping of in vivo human knee cartilage at 7T. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis JR, Koch GG. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]