Abstract

We reported the management of a life-threatening condition as a large tracheo-gastric fistula involved the carina, the left and the right bronchus that complicated Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. An urgent right thoracotomy was performed and the tracheal defect was covered with a reversed pedicled pericardial patch reinforced with an intercostal muscle flap. Cervical esophagostomy and a feeding jejunostomy completed the operation. Five months later, the continuity of gastrointestinal tract was restored using a transverse colon.

Keywords: Tracheo-gastric fistula, esophagectomy, esophageal cancer

Introduction

Tracheo-gastric fistula after esophagectomy for cancer is a rare and life-threatening clinical condition (1,2). Surgery, when feasible, is the treatment of choice despite the large size of the fistula makes it challenging. Herein, we described a new technique as the use of pericardial and intercostal flaps for closing a huge tracheo-gastric fistula after esophagectomy for cancer.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old male was referred to our institution for managment of squamous cell carcinoma of the middle-third of the esophagus. No induction therapy was perfomed and all diagnostic exams excluded lymph node involvement and distant metastases.

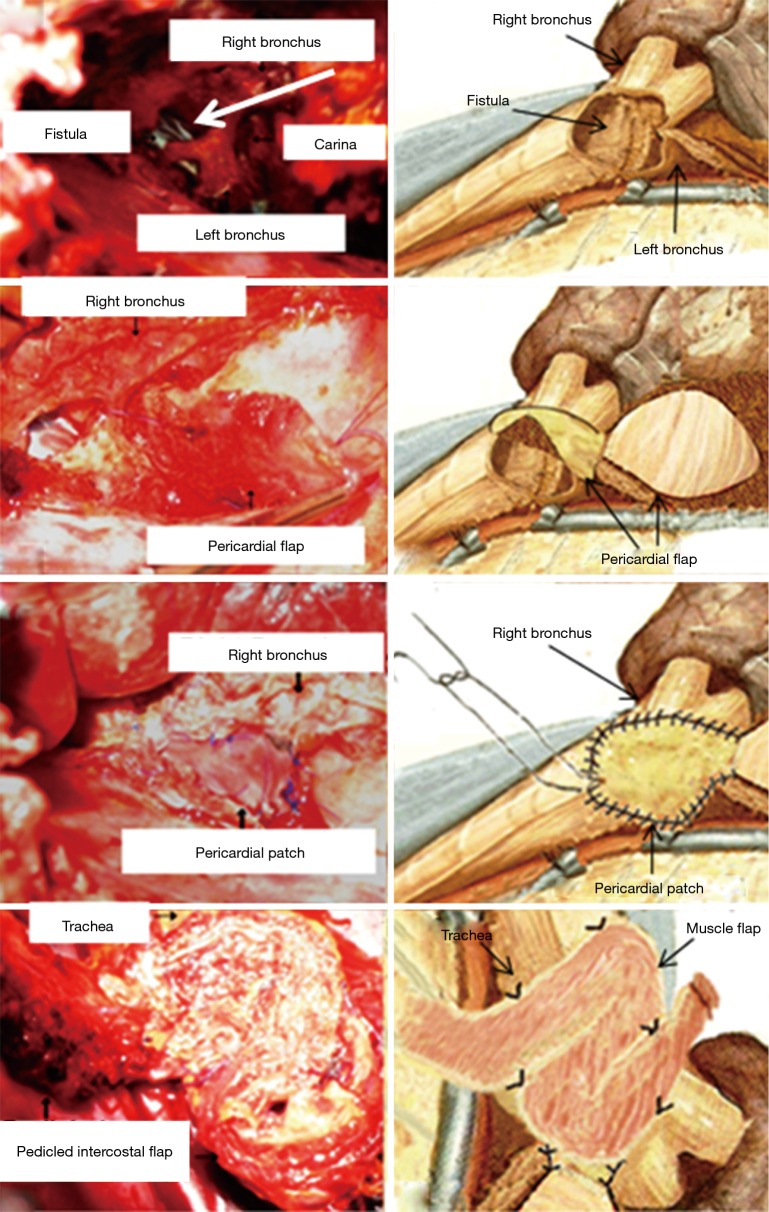

The patient underwent a subtotal esophagectomy and the gastric conduit was anastomosed to the cervical esophagus through the posterior mediastinal route using a circular stapler. The patient was extubated in post-operative day-1 (POD-1) and discharged from the intensive care unit (ICU) in POD-3. A cervical emphysema occurred in POD-7. Esophago-gastroscopy and flexible bronchoscopy showed the necrosis of gastric tubule, distally to the cervical anastomosis, and a huge fistula that involved the carina, the main right and left bronchus (Figure 1). Following, the patient had an acute severe respiratory failure due to right hypertensive pneumothorax with left mediastinal shift and extensive subcutaneous emphysema. He was immediately intubated with an 8-mm side cuffed oral tube that was endoscopically placed within left main bronchus to overcome the carinal defect and assure the ventilation. A right thoracotomy was immediately performed. The excision of gastric tubule and all necrotic tissues showed a carinal defect of 4 cm in size (Figure 2A,B). Pericardium was pediculized (Figure 2C,D) and used to reconstruct the pars membranacea of the trachea (Figure 2E,F). Then, endotracheal tube was proximally retired into the trachea to allow the ventilation of both lungs. Despite the lack of air leaks after instillation of saline solution, we noticed a paradoxical movement of the pericardial flaps due to positive pressure ventilation. Thus, an intercostal muscle flap was used to reinforce the reconstruction of the posterior wall of the trachea (Figure 2G,H). An end-cervical esophagostomy, an esophageal diversion and a feeding jejunostomy completed the operation. Four drains were left in site, one within neck, two within the mediastinum and one in abdomen. The patient was ventilated with low-tidal volumes and airway pressures to preserve tracheal closure. Repeated bronchoscopes were performed to exclude any defect of fistula closure and to clean air way from secretions. Antibiotics were given based on airway and blood cultures. Enteral feeding was administered since the 5th post-operative day and all drains were removed on 15 days after. Bronchoscopy performed on 27th POD showed the healing of tracheal defect and normal air-way patency. Patient was extubated on 28th POD and discharged 5 days later.

Figure 1.

Flexible bronchoscopy showed the tracheo-esophageal fistula (3). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1182

Figure 2.

Tracheal defect with tracheal tube (white arrow) within the left main bronchus (A-B); mobilization of pericardial flap without torsion (C-D); fistula closure with pericardial flap (E-F); reinforcement of closure with intercostal muscle flap (G-H).

Three months’ follow-up bronchoscopy showed a normal air-way patency in absence of fistula and/or stenosis. The stitches were well evident (Figure 3) but they were expectorated few weeks later. Five months later, a successfully esophageal replacement with a colon conduit was performed. Patient died 9 months later for abdominal recurrence.

Figure 3.

Complete closure of the fistula with stitches still inside the right and left bronchus.

Discussion

A fistula between the trachea and the gastric tube related to esophagectomy is a rare and life-threatening clinical condition (1,2). Despite conservative and endoscopic treatments have been proposed (4-7), surgery remains the treatment of choice when feasible (7-11). However, it could be particularly challenging, as in the present case, due to the large dimension of the fistula (about 4 cm) and its extension (involving carina, main left and right bronchus).

Impaired blood supply to the gastric tube was the most likely explanation for development of fistula, in the present case. The necrotic gastric tubule invaded the carina and the main left and right bronchus. The critical respiratory condition of the patient required an emergency surgery. Over the years, several strategies have been proposed to repair tracheo-bronchial fistula using alloplastic, prosthetic materials, and intra or extra-thoracic muscle flaps (7-15). However, all these procedures resulted to be unfeasible for closure our defect. The direct closure of the fistula was at high risk of failure due to the extension of local infection. Similarly, its closure using autologous or bovine pericardium, pleural or extra-thoracic muscles was contraindicated since the depth of these flaps was too thin and, thus, they could damaged by the positive pressure ventilation. Song et al. (16) reported a successful gastrotracheal fistula closure with a twisted pericardial flap after Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. Gorenstein et al. (17) and Foroulis et al. (18) reported the use of a free pericardial patch for closing a tracheal laceration during a transhiatal esophagectomy. In this case, we also used a pericardial patch to repair the carinal defect but conversely to previous experiences (17,18), the pericardium flap was not twisted neither used as free to preserve its vascularization. Philippi et al. (19) described the use of intercostal muscle flaps for reconstruction of posterior wall of trachea in dogs. Its flap consisted of three intercostal muscles with their pedicle applied to the posterior wall of trachea with the pleural aspect facing the tracheal lumen. We fashioned only a single intercostal muscle flap that was fixed over the pericardial patch in order to reinforce the tracheal reconstruction and prevented any damage due to positive pressure ventilation. In addition, the intercostal muscle flap assisted the neo-vascularization of the pericardial flap and thus facilitated the physiological healing of the lesion (20). Despite the prolonged mechanical ventilation (28 days), no damage of closure occurred.

In conclusion, our new technique as the use of pericardial patch reinforced with intercostal flap could be useful for surgeons in the management of a rare and challenging situation as tracheo-gastric fistula after esophagectomy for cancer.

Acknowledgements

None.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Buskens CJ, Hulscher JB, Fockens P, et al. Benign tracheo-neo-esophageal fistulas after subtotal esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:221-4. 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02701-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasuda T, Sugimura K, Yamasaki M, et al. Ten cases of gastro-tracheobronchial fistula: a serious complication after esophagectomy and reconstruction using posterior mediastinal gastric tube. Dis Esophagus 2012;25:687-93. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caronia FP, Fiorelli A, Santini M, et al. Flexible bronchoscopy showed the tracheo-esophageal fistula. Asvide 2016;3:410. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1182

- 4.Fiorelli A, Esposito G, Pedicelli I, et al. Large tracheobronchial fistula due to esophageal stent migration: Let it be! Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2015;23:1106-9. 10.1177/0218492315587816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang F, Yu H, Zhu MH, et al. Gastrotracheal fistula: treatment with a covered self-expanding Y-shaped metallic stent. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:1032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santini M, Fiorello A, Cappabianca S, et al. Unusual case of Boerhaave syndrome, diagnosed late and successfully treated by Abbott's T-tube. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:539-40. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorelli A, Frongillo E, Santini M. Bronchopleural fistula closed with cellulose patch and fibrin glue. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2015;23:880-3. 10.1177/0218492315577725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marty-Ané CH, Prudhome M, Fabre JM, et al. Tracheoesophagogastric anastomosis fistula: a rare complication of esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:690-3. 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00284-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalmár K, Molnár TF, Morgan A, et al. Non-malignant tracheo-gastric fistula following esophagectomy for cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;18:363-5. 10.1016/S1010-7940(00)00520-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li YD, Li MH, Han XW, et al. Gastrotracheal and gastrobronchial fistulas: management with covered expandable metallic stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006;17:1649-56. 10.1097/01.RVI.0000236609.33842.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kron IL, Johnson AM, Morgan RF. Gastrotracheal fistula: a late complication after transhiatal esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1989;47:767-8. 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90139-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poje CP, Keane W, Atkins JP, Jr, et al. Tracheo-gastric fistula following gastric pull-up. Ear Nose Throat J 1991;70:848-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caronia FP, Fiorelli A, Santini M, et al. A persistent tracheocutaneous fistula closed with two hinged skin flaps and rib cartilage interpositional grafting. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;64:625-8. 10.1007/s11748-015-0529-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caronia FP, Fiorelli A, Zanchini F, et al. Reconstruction with a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap after left first rib and clavicular chest wall resection for a metastasis from laryngeal cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;64:294-7. 10.1007/s11748-014-0485-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caronia FP, Fiorelli A, Arrigo E, et al. Management of subtotal tracheal section with esophageal perforation: a catastrophic complication of tracheostomy. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E337-9. 10.21037/jtd.2016.03.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song SW, Lee HS, Kim MS, et al. Repair of gastrotracheal fistula with a pedicled pericardial flap after Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:716-7. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorenstein LA, Abel JG, Patterson GA. Pericardial repair of a tracheal laceration during transhiatal esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:784-6. 10.1016/0003-4975(92)91034-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foroulis CN, Simeoforidou M, Michaloudis D, et al. Pericardial patch repair of an extensive longitudinal iatrogenic rupture of the intrathoracic membranous trachea. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2003;2:595-7. 10.1016/S1569-9293(03)00142-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philippi D, Valleix D, Descottes B, et al. Anatomic basis of tracheobronchial reconstruction by intercostal flap. Surg Radiol Anat 1992;14:11-5. 10.1007/BF01628036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rendina EA, Venuta F, Ricci P, et al. Protection and revascularization of bronchial anastomoses by the intercostal pedicle flap. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994;107:1251-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]