Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the prevalence and clinical features of retained symptomatic common bile duct (CBD) stone detected after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) in patients without preoperative evidence of CBD or intrahepatic duct stones.

Methods

Of 2,111 patients who underwent cholecystectomy between September 2007 and December 2014 at Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, 1,467 underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallbladder stones and their medical records were analyzed. We reviewed the clinical data of patients who underwent postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for clinically significant CBD stones (i.e., symptomatic stones requiring therapeutic intervention).

Results

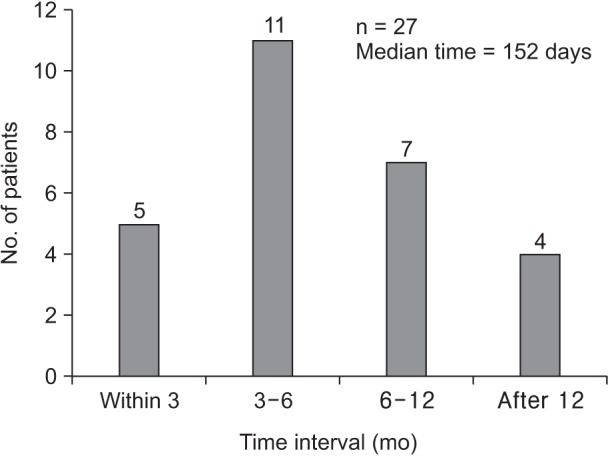

Overall, 27 of 1,467 patients (1.84%) underwent postoperative ERCP after LC because of clinical evidence of retained CBD stones. The median time from LC to ERCP was 152 days (range, 60–1,015 days). Nine patients had ERCP-related complications. The median hospital stay for ERCP was 6 days.

Conclusion

The prevalence of clinically significant retained CBD stone after LC for symptomatic cholelithiasis was 1.84% and the time from LC to clinical presentation ranged from 2 months to 2 years 9 months. Therefore, biliary surgeons should inform patients that retained CBD stone may be detected several years after LC for simple gallbladder stones.

Keywords: Gallstones, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Morbidity

INTRODUCTION

Biliary surgeons may experience frustration when patients who undergo cholecystectomy subsequently present with retained common bile duct (CBD) stones after discharge, despite the absence of CBD stones on preoperative or postoperative check-ups. Such patients are likely to be referred to internal medicine specialists for diagnosis and subsequent treatment. The original surgeon is likely to feel culpable for declaring complete recovery and may suffer a loss of rapport with the patient. Other issues include the medical expenditure associated with the diagnosis and treatment of retained CBD stones, the risk of complications associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and increased patient distress [1,2].

CBD stones are detected in 11%–25% of patients with gallbladder (GB) stones [3], and about 10% of patients who undergo cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis have CBD stones, including silent stones [4,5,6]. Now that laparoscopic cholecystectomy has replaced open surgery as the gold standard method for treating symptomatic cholelithiasis [7,8,9,10], it is essential to address the strategy used for the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of unexpected CBD stones.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of clinically significant CBD stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis, in order to redefine the postoperative checkup plan and ultimately minimize its sociomedical impact. Our results should help surgeons to understand the clinical consequence of symptomatic cholelithiasis and facilitate the introduction of cost-effective postoperative strategies.

METHODS

Study design and patients

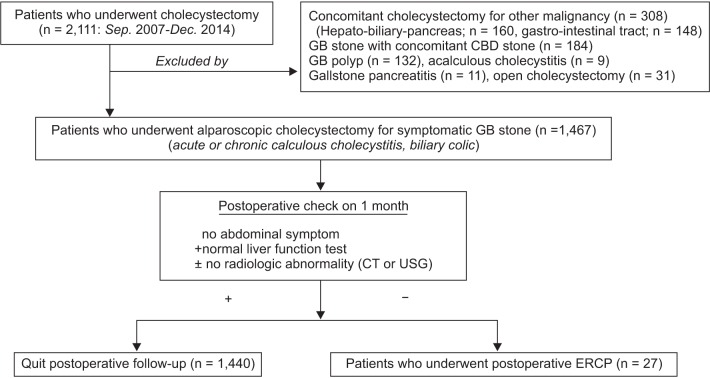

In this retrospective single-center study, we retrieved the medical records of all patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis (acute or chronic calculous cholecystitis and for biliary colic) who had no evidence of CBD or intrahepatic duct stone on preoperative work up between September 2007 and December 2014 at Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University (SMG-SNU) Boramae Medical Center. Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University (SMG-SNU) Boramae Medical Center is a secondary referral center that performs over 300 laparoscopic cholecystectomies annually. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Seoul National University Hospital of Boramae Medical Center (approval number: 26-2015-76). We initial searched electronic medical records to identify patients who underwent 'cholecystectomy' in the study period. From these, we excluded patients for the following reasons: (1) cholecystectomy was performed for GB polyps; (2) cholecystectomy was performed concomitantly to surgery for another malignant disease; (3) preoperative diagnosis of GB stone with concomitant CBD stone; (4) cholecystectomy was performed for acalculous cholecystitis; (5) cholecystectomy was performed for gallstone pancreatitis; or (6) cholecystectomy was performed via an open method (Fig. 1). After excluding ineligible patients, we further investigated the characteristics of patients who underwent postoperative ERCP owing to clinically significant CBD stones. The patients are expected to have had no clinical symptoms or signs of CBD stones in routine preoperative and postoperative assessments, including laboratory and radiologic tests.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of the selection for patients. GB, gallbladder; CBD, common bile duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; USG, ultrasonography.

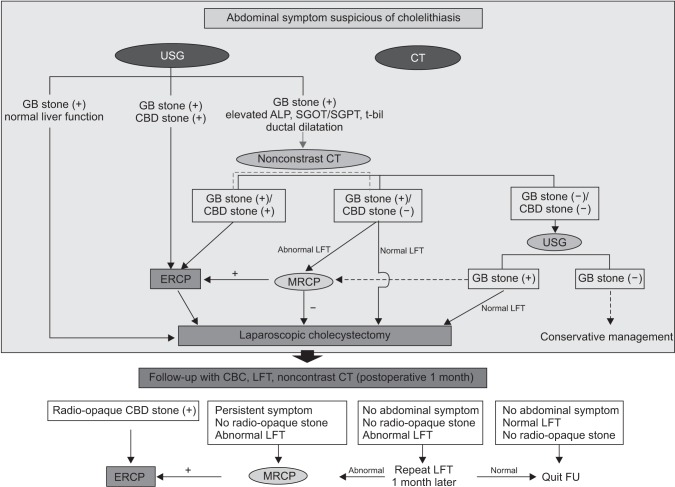

SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center guidelines for preoperative and postoperative management for symptomatic cholelithiasis (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Institutional guideline of preoperative and postoperative management of the patient who has abdominal symptoms suspecting cholelithiasis. USG, ultrasonography; GB, gallbladder; CBD, common bile duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; LFT, liver function test; FU, follow-up.

The diagnostic workup of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis usually begins with biochemical tests of liver function and systemic inflammation and diagnostic imaging (abdominal ultrasonography or CT). Any imaging data transferred to the internal medicine department at the time of the patient's referral should be reevaluated by a radiologist. Although ultrasonography provides reliable imaging of the bile duct in most cases, its accuracy is sometimes limited by colonic gas, obesity, anatomical variations, and the sonographer's experience. The specialist should then determine whether any blood biochemical markers (e.g., alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, aspartate transaminase, and alanine transaminase) are elevated. If ultrasonography is unable to evaluate the entire bile duct in patients with abnormal liver function markers, noncontrast CT should be performed to rule-out potential CBD stone. Noncontrast CT should be favored because fasting and the use of contrast media are generally unnecessary and it is relatively inexpensive, although it is unable to detect radiolucent stones. Contrast-enhanced CT scan can also be used as a primary imaging modality, and this is usually performed in an emergency room or at another hospital. If suspected GB stone is invisible on CT images, ultrasonography could be performed as an ancillary imaging modality. The high likelihood of a CBD stone in patients with typical abdominal symptoms and liver function test abnormalities without visible CBD stone can prompt some specialists to perform magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). In our institution, our policy is to remove all CBD stones by ERCP first, and then perform laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperative cholangiography is not routinely performed. Postoperatively, all patients are checked with biochemical tests (complete blood cell count and liver function tests) and non-contrast CT at one month after LC.

Data retrieval

The clinical data of the eligible patients were retrieved and retrospectively reviewed. Preoperative data included demographic characteristics, surgical indications, preoperative radiologic imaging modality, and preoperative laboratory test results. Perioperative data included the characteristics of the GB stone, operation time, and elective/emergent surgery. Postoperative data included the follow-up imaging modality, route of admission (outpatient clinic or emergency center), mode of presentation (reason for admission or chief complaint), reason for and outcome of ERCP, time from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to ERCP, length of hospital stay for ERCP, and complications of ERCP.

Statistics analysis

Continuous, normally distributed variables are presented as the median and range, while categorical variables are presented as the number (percent). All analyses were performed using PASW software ver. 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Between September 2007 and December 2014, 2,111 cholecystectomies were identified by reviewing the electronic medical records at SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center. A total of 644 procedures (30.5%) were excluded because of the exclusion criteria (132: cholecystectomy performed for GB polyps; 308: cholecystectomy was performed concomitantly to surgery for another malignant disease [160: hepato-pancreasbiliary malignancy, 148: gastrointestinal malignancy]; 184: GB stone with concomitant presence of CBD stones, 9: acalculous cholecystitis; 11: gallstone pancreatitis; 31: open cholecystectomy). After applying these criteria, 1,467 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic GB stone were reviewed. A total of 27 of 1,467 patients (1.84%) who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy subsequently underwent ERCP. These patients had no abdominal symptoms, or abnormal radiologic or laboratory findings on routine postoperative check-up done at postoperative 1 month.

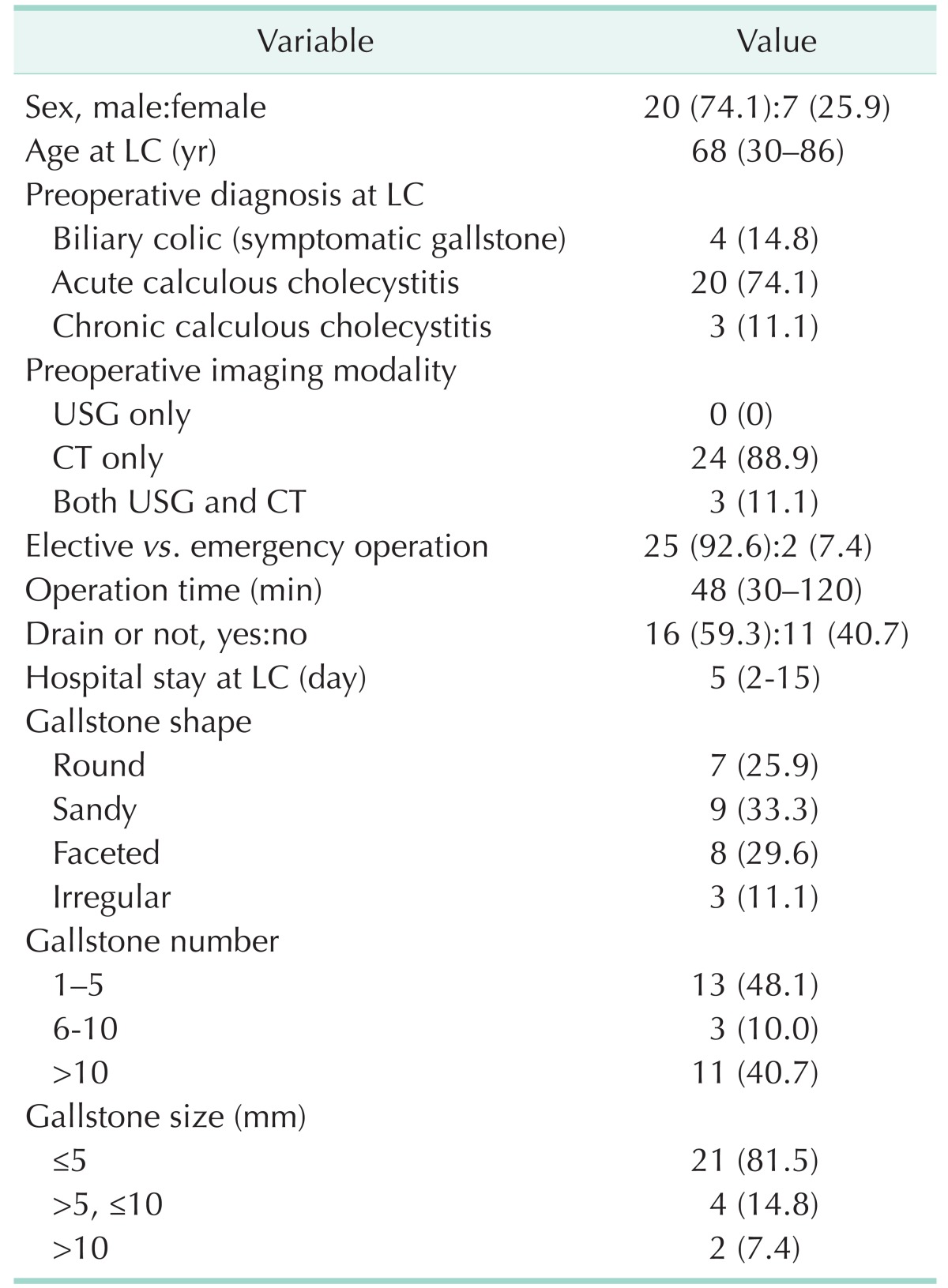

Patient demographics and clinical features of the initial operation

Patient demographics and perioperative data are listed in Table 1. Twenty patients (74.1%) were male and 7 (25.9%) were female. The patients were initially diagnosed with acute calculous cholecystitis (n = 20, 74.1%), biliary colic (n = 4, 14.8%), and chronic calculous cholecystitis (n = 3, 11.1%). Twenty-four patients (88.9%) only underwent contrast-enhanced abdominal CT for preoperative diagnostic imaging and 3 patients (11.1%) underwent abdominal ultrasonography and CT. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed for emergent reasons in 2 patients (7.4%); the other procedures were done electively (n = 25, 92.6%) after the patients' condition had improved with intravenous hydration and antibiotics. The gallstone was ≤ 5 mm in diameter in 21 patients (81.5%), 6–10 mm in 4 patients, and >10 mm in 2 patients (7.4%). The median operation time was 48 min (range, 30–120 minutes). The median hospital stay after surgery was 5 days (range, 2–15 days). All patients showed excellent postoperative recovery and their liver function had normalized by 1 month after surgery. Routine abdominal ultrasonography or noncontrast CT scans showed no abnormalities.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical features of the patients at initial operation (n = 27).

Values are presented as number (%) or median (range).

LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; USG, ultrasonography.

Time between LC and ERCP

The median age of patients at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was 68 years and the median age of at the time of ERCP was 69 years. The median time from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to ERCP was 152 days (range, 60–1,015 days) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The time interval from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

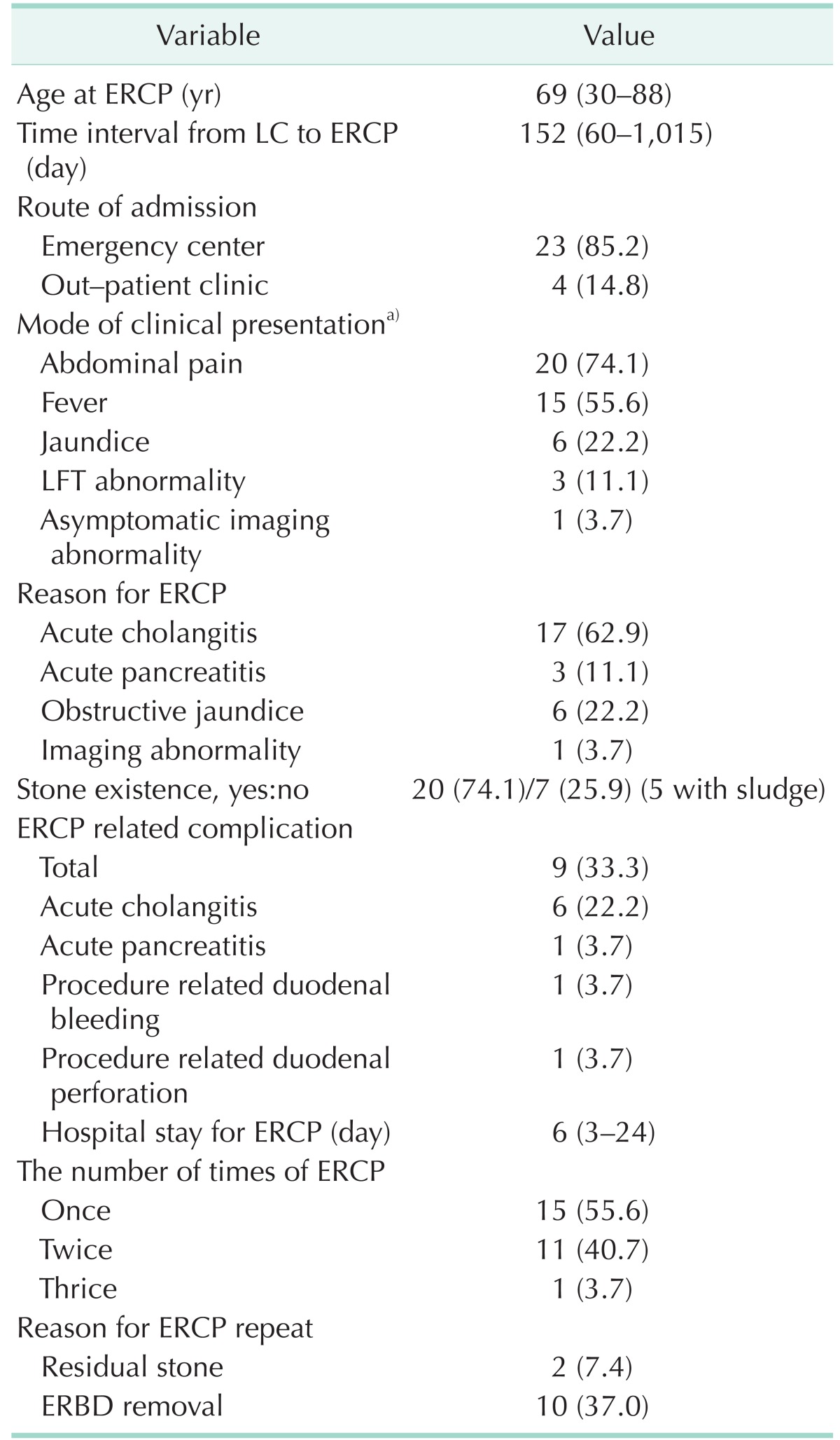

Clinical features of retained CBD stones

The clinical findings associated with symptomatic retained CBD stone are listed in Table 2. Twenty-three patients (85.2%) were readmitted via an emergency center and 4 patients (14.8%) via an outpatient clinic. The clinical symptoms included abdominal pain in 22 patients (74.1%), fever in 15 (55.6%), and jaundice in 6 (22.2%). Interestingly, 3 patients (11.1%) had liver function abnormalities without abdominal symptoms and 1 patient (3.7%) had imaging abnormalities alone. ERCP was performed because of acute cholangitis in 17 patients (62.9%), obstructive jaundice in 6 (22.2%), acute pancreatitis in 3 (11.1%), and asymptomatic imaging abnormalities in 1 (3.7%); some patients had multiple clinical indications. The retained CBD stones thought to cause these symptoms were detected by ERCP in 20 patients (74.1%). However, CBD sludge was found without any stones in 5 patients (18.5%), and 2 patients (7.4%) lacked evidence of either CBD stones or sludge. Twelve patients (44.4%) underwent ERCP multiple times; twice in 11 patients and thrice in 1 patient to remove a previously deployed plastic stent in 10 patients (37.0%) and to remove a residual CBD stone despite bile duct clearance via the prior ERCP in 2 patients (7.4%). ERCP-related complications occurred in 9 patients (33.3%), and included acute cholangitis in 6 patients, and acute pancreatitis, duodenal bleeding, and duodenal perforation in 1 patient each. The median hospital stay for ERCP was 6 days (range, 3–24 days).

Table 2. Clinical findings associated with symptomatic retained common bile duct stones (n = 27).

Values are presented as number (%) or median (range).

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ERBD, endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage.

a)Clinical presentation could be overlapped in several patients.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study determined the prevalence of clinically significant retained CBD stones in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis without evidence of CBD stones in preoperative and postoperative workup, based on data from a single center. Surgeons are likely to feel embarrassment when they encounter patients with this postoperative clinical course. Collins et al. [6] reported that in nonjaundiced patients with normal duct son transabdominal ultrasound, the prevalence of CBD stone at the time of cholecystectomy is unlikely to exceed 5%. Considering the prevalence of silent CBD stone of 3%–5% [4,5,6,11,12] and the proportion of patients who might have visited other institutions in whom the diagnosis of CBD stones was potentially missed, our data do not show the prevalence of all retained CBD stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, only the prevalence of clinically significant retained CBD stones.

Peng et al. [3] reported that the overall incidence of CBD stones with GB stones was 11%–25%. It was comparable when considering sum of 184 patients of GB stones with concommitant CBD stones (184 of 2,111; 8.7%) and 20 patients who really had CBD stones after LC operation for symptomatic GB stones (20 of 1,467; 1.4%) could make up 10.1% in present study.

Primary CBD stones are more common in Southeast Asian populations than in other populations, and are usually described in the ERCP report as 'mud'-like stones, not laminated stones, that form in the CBD following biliary infection and stasis [13,14]. Secondary CBD stones, which originate in the GB and migrate into the CBD, have a typical appearance of laminated GB stones [15]. In this study, ERCP showed that 20 patients had retained CBD stones, which might be as secondary stones rather than primary stones. Only 5 patients had sludge without definite CBD stones, and small stones could be spontaneously excreted [16,17]. Therefore, most of the clinically significant retained CBD stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in our study appear to have formed in the GB rather than in the CBD. In addition, 23 patients (85%) underwent ERCP within 1 year after cholecystectomy, and therefore satisfy the criteria for secondary CBD stones, based on the criteria for primary CBD stone proposed by Johns Hopkins Hospital [18] as follows: (1) previous cholecystectomy with or without common duct exploration; (2) an asymptomatic period of ≥2 years after initial biliary tract surgery; (3) presence of soft, easily crushable, light-brown stones or sludge in the CBD; and (4) no evidence of a long cystic duct remnant or a biliary stricture resulting from the prior surgery.

There are several mechanisms that explain the postoperative formation of retained CBD stone in patients without preoperative evidence. (1) The stones spontaneously migrate from the GB between preoperative imaging and surgery. (2) The stones migrate during operative manipulation. This is likely to occur if the stone is impacted in the cystic duct at the time of preoperative imaging, particularly if no stones are found in the GB after cholecystectomy. (3) Asymptomatic, radiolucent stones are already present in the CBD but cannot be detected by CT. This indicates that the GB and CBD stones have different origin. (4) Preoperative ultrasonography missed the CBD stones because they were obscured by colonic gas or obesity, and there was no evidence of bile duct dilatation and liver function test abnormalities. (5) New CBD stones developed during the postoperative period (i.e., primary CBD stone formation). Because any of these situations may occur in clinical settings, surgeons should notify their patients that CBD stone may be detected sometime after surgery, especially in patients who were originally diagnosed with multiple and small-sized GB stones.

Recently, Kim et al. [19] retrospectively reviewed a database of 1,455 LCs and evaluated whether there was a risk factor in patients who underwent ERCP within 6 months after LC, they compared admission route, preoperative biochemical liver function test, number of stones, gallstone size, adhesion around GB, wall thickening of GB, and existence of acute cholecystitis. They suggested that longer operation time and acute cholecystitis could be possibly associated with prevalence of undergoing postoperative ERCP in patients with LC for symptomatic GB stone disease. That's because the operation time becomes more protracted, the probability of gallstone transmission to the CBD through the cystic duct will rise. It means that most of CBD stones they found in ERCP had come from GB.

Cost-effective diagnosis and subsequent management of retained CBD stones are controversial. The initial workup of patients with suspected cholelithiasis is usually involves transabdominal ultrasonography or CT at an outpatient clinic or emergency center, depending on the patient's clinical setting, the institutional protocol, or the attending clinician's preference. Because transabdominal ultrasonography is often limited in terms of the ability to detect distal CBD stones, it is possibly inadequate to identify patients who are highly likely to have CBD stones. In addition, it is undeniable that CT shows limited ability to detect calcium-free radiolucent stones. Although recent studies [20,21] suggested that helical CT cholangiography can be used to diagnose CBD stones with sensitivity and specificity similar to magnetic resonance cholangiography, its use as a primary radiologic imaging modality seems to be inappropriate from a cost-effectiveness perspective. In addition, Ammori et al. [22] proposed that a "wait and see" policy of observation alone for patients with small bile duct calculi detected at intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) during laparoscopic cholecystectomy appears to be safe, and is more cost-effective than routine postoperative ERCP. Furthermore, some studies have suggested that the most cost-effective treatment strategy for most patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis involves laparoscopic cholecystectomy with routine IOC, as IOC can help laparoscopists to visualize the biliary anatomy and detect unexpected CBD stones [23,24]. However, it remains debated whether IOC provides sufficient benefits in terms of its efficacy and safety to justify its routine application. Indeed, several studies [6,25] have shown that IOC in addition to routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy of symptomatic cholelithiasis did not improve the detection rate of unexpected CBD stones or bile duct injury, but did increase the operation time. IOC can also complicate the surgical procedure and increase the risk of adverse complications. Needless to say, MRCP and endoscopic ultrasonography show high diagnostic accuracy for CBD stones owing to their accurate visualization of the biliary system without invasive instrumentation. However, the appropriate timing of these procedures is being investigated with respect to their cost-effectiveness. Bahram and Gaballa [26] advocated routine preoperative MRCP to reduce the incidence of postoperative complications and to detect unexpected CBD stone. However, other studies [12,27] opposed routine MRCP owing to its poor cost-effectiveness. Nevertheless, if CBD stones are strongly suspected in patients with bile duct dilatation, the presence of liver function abnormalities should justify the use of MRCP or endoscopic ultrasonography.

Per Videhult et al. [28] conducted a prospective, nonselected, population-based study and reported that the numbers of falsepositive and false-negative findings were relatively high and that fewer than half of the patients with elevated alkaline phosphatase or bilirubin were found to have CBD stone on IOC; alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels were the best predictors of CBD stones. In our institution, unenhanced CT is routinely performed postoperatively to detect retained CBD stones along with laboratory measurement of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin concentrations. Irrespective of whether symptoms are persistent, the combination of unenhanced CT and alkaline phosphatase tests could offer a reliable, technically simple, and economical postoperative screening strategy to detect potential retained CBD stones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis.

In the present study, the median time from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to ERCP was 152 days (range, 2 months to 1,015 days). Cox et al. [29] reported a median time from LC to ERCP of 4 years. They reviewed 61 patients who underwent ERCP after laparoscopic cholecystectomy between 1994 and 2010, of which 52 (85.2%) underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy at another institution. The distribution of the time from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to ERCP was skewed, with one-quarter presenting within 12 months and one-half by 4 years, but several patients underwent ERCP at >10 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Therefore, the main reason for the difference between the reported times of their study and our study is the difference in the follow-up period, which was 7 years in our study versus 16 years in the study by Cox et al. [29].

In summary, the prevalence of clinically significant retained CBD stone after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in this study was 1.84%. The median time from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to ERCP was 152 days, ranging from postoperative 2 months to 2 years 9 months. Based on these findings, we recommend that biliary surgeons should notify their patients in advance of the risk of retained CBD stone, though low incidence, after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis and its necessity of following invasive treatment.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Bhat M, Romagnuolo J, da Silveira E, Reinhold C, Valois E, Martel M, et al. Randomised clinical trial: MRCP-first vs. ERCP-first approach in patients with suspected biliary obstruction due to bile duct stones. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1045–1053. doi: 10.1111/apt.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris S, Gurusamy KS, Sheringham J, Davidson BR. Cost-effectiveness analysis of endoscopic ultrasound versus magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in patients with suspected common bile duct stones. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng WK, Sheikh Z, Paterson-Brown S, Nixon SJ. Role of liver function tests in predicting common bile duct stones in acute calculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1241–1247. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickkholgh A, Soltaniyekta S, Kalbasi H. Routine versus selective intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a survey of 2,130 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:868–874. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart SA, Simpson TI, Alvord LA, Williams MD. Routine intraoperative laparoscopic cholangiography. Am J Surg. 1998;176:632–637. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O'Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239:28–33. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000103069.00170.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randial Perez LJ, Fernando Parra J, Aldana Dimas G. The safety of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (<48 hours) for patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Cir Esp. 2014;92:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawe SR, Windsor JA, Broeders JA, Cregan PC, Hewett PJ, Maddern GJ. A systematic review of surgical skills transfer after simulation-based training: laparoscopic cholecystectomy and endoscopy. Ann Surg. 2014;259:236–248. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SC, Choi BJ, Kim SJ. Two-port cholecystectomy maintains safety and feasibility in benign gallbladder diseases: a comparative study. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1014–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coccolini F, Catena F, Pisano M, Gheza F, Fagiuoli S, Di Saverio S, et al. Open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2015;18:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kullman E, Borch K, Lindstrom E, Svanvik J, Anderberg B. Value of routine intraoperative cholangiography in detecting aberrant bile ducts and bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1996;83:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nebiker CA, Baierlein SA, Beck S, von Flue M, Ackermann C, Peterli R. Is routine MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) justified prior to cholecystectomy? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:1005–1010. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki N, Takahashi W, Sato T. Types and chemical composition of intrahepatic stones. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1984;152:71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman HS, Magnuson TH, Lillemoe KD, Frasca P, Pitt HA. The role of bacteria in gallbladder and common duct stone formation. Ann Surg. 1989;209:584–591. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198905000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tazuma S. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and classification of biliary stones (common bile duct and intrahepatic) Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonatsos G, Leandros E, Dourakis N, Birbas C, Delibaltadakis G, Golematis B. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperative findings and postoperative complications. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:889–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dexter SP, Martin IG, Marton J, McMahon MJ. Long operation and the risk of complications from laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1997;84:464–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saharia PC, Zuidema GD, Cameron JL. Primary common duct stones. Ann Surg. 1977;185:598–604. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197705000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim BS, Joo SH, Cho S, Han MS. Who experiences endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstone disease? Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016;90:309–314. doi: 10.4174/astr.2016.90.6.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo S, Isayama H, Akahane M, Toda N, Sasahira N, Nakai Y, et al. Detection of common bile duct stones: comparison between endoscopic ultrasonography, magnetic resonance cholangiography, and helical-computed-tomographic cholangiography. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okada M, Fukada J, Toya K, Ito R, Ohashi T, Yorozu A. The value of drip infusion cholangiography using multidetector-row helical CT in patients with choledocholithiasis. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:2140–2145. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2820-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ammori BJ, Birbas K, Davides D, Vezakis A, Larvin M, McMahon MJ. Routine vs "on demand" postoperative ERCP for small bile duct calculi detected at intraoperative cholangiography. Clinical evaluation and cost analysis. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1123–1126. doi: 10.1007/s004640000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horwood J, Akbar F, Davis K, Morgan R. Prospective evaluation of a selective approach to cholangiography for suspected common bile duct stones. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:206–210. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12628812458293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown LM, Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Brasel KJ, Inadomi JM. Cost-effective treatment of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis and possible common bile duct stones. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:1049–1060. 1060.e1–1060.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding GQ, Cai W, Qin MF. Is intraoperative cholangiography necessary during laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2147–2151. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahram M, Gaballa G. The value of preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in management of patients with gall stones. Int J Surg. 2010;8:342–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epelboym I, Winner M, Allendorf JD. MRCP is not a cost-effective strategy in the management of silent common bile duct stones. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:863–871. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Videhult P, Sandblom G, Rudberg C, Rasmussen IC. Are liver function tests, pancreatitis and cholecystitis predictors of common bile duct stones? Results of a prospective, population-based, cohort study of 1171 patients undergoing cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:519–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox MR, Budge JP, Eslick GD. Timing and nature of presentation of unsuspected retained common bile duct stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2033–2038. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3907-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]