Highlights

-

•

Splenic rupture is a rare complication of community acquired pneumonia.

-

•

Clinician vigilance is required to prevent subsequent morbidity and mortality.

-

•

Post-operative follow-up must address the potential sequelae of asplenia.

-

•

This research did not receive any specific funding and the authors declare no conflicting interests.

Keywords: Case report, Community acquired pneumonia, Splenic rupture, Emergency splenectomy

Abstract

Introduction

Splenic rupture is a rare but potentially lethal complication of community acquired pneumonia.

Presentation of case

We present an unusual case of haemorrhagic shock following splenic rupture requiring emergency splenectomy in a 49 year old female with community acquired pneumonia.

Discussion

The epidemiology, aetiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, investigation, management and outcomes of atraumatic splenic rupture are discussed.

Conclusion

Atraumatic splenic rupture is a rare but potentially fatal complication of numerous disease processes including pneumonia. A high index of suspicion and a thorough and systematic approach to the deteriorating patient is required to prevent related morbidity and mortality. Post-operative follow-up must address the potential sequelae of asplenia.

1. Introduction

Splenic rupture is a rare but potentially fatal complication of community acquired pneumonia. We present an unusual case of haemorrhagic shock due to splenic rupture in a 49 year old female with community acquired pneumonia who required emergency splenectomy in a rural hospital.

2. Presentation of case

The patient presented with low back pain radiating down her right leg following three weeks of intractable cough productive of green sputum. She reported no chest pain, shortness of breath or fevers, no paraesthesia or weakness of the lower limbs and no urinary or bowel symptoms. She had completed a course of oral cephalexin prescribed by her general practitioner. Her only medical history was hypertension and chronic low-back pain. She smoked 20 cigarettes per day with a 15 pack year smoking history.

On examination she had no respiratory distress and her vital signs were normal. She had bronchial breath sounds in the right lung mid to lower zones with coarse crepitations. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender. She had an antalgic gait but normal sensation, power and reflexes in the lower limbs. Her white cells were 19.2 × 109/L with a neutrophilia and chest radiograph demonstrated an obscured right heart border favoured to represent infective consolidation of the middle lobe of the right lung.

She was diagnosed with community acquired pneumonia of the right middle lobe. The cough was thought to have precipitated the low back pain. She was commenced on benzyl penicillin, doxycycline and analgesics and was admitted under the medical team.

On the second day of admission she had a medical emergency team review for hypotension and presyncope. She reported new onset epigastric/chest pain in addition to her back pain. She was pale with a heart rate of 78 bpm and blood pressure 66/38 mmHg. Her chest examination was unchanged and her abdomen remained soft. Her haemoglobin had dropped from 115 g/L to 77 g/L in three hours.

She was identified as being in shock, likely haemorrhagic. Initially aortic dissection, rupture of an aortic aneurysm or haemorrhage from a peptic ulcer was suspected. The differential diagnosis included sepsis secondary to her pneumonia or obstructive shock secondary to pulmonary embolism. Bilateral large bore intravenous access was obtained and fluid resuscitation was commenced followed by transfusion of red blood cells. She was given intravenous ceftriaxone. She was moved to the high dependency unit and surgical review was obtained. She was haemodynamically responsive to resuscitation therefore an urgent computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of her chest and abdomen was performed (Fig. 1). This revealed a ruptured spleen with a large perisplenic haematoma, large haemoperitoneum and active bleeding in portal venous sequences as well as bilateral pulmonary consolidation without pulmonary embolism. The presumptive diagnosis was splenic rupture secondary to repeated coughing in community acquired pneumonia.

Fig. 1.

CT abdomen with contrast in the transverse plane at the level of the coeliac trunk demonstrating perisplenic haematoma and haemoperitoneum.

The patient was immediately taken to the operating theatre for an emergency laparotomy. She had a vertical midline upper abdominal laparotomy and a large haematoma was removed revealing ongoing bleeding. The spleen was found to be nearly avulsed but not enlarged. The splenophrenic ligament appeared incomplete, with partial rupture of the spleen under the ligament, and the splenonephric ligament was absent or avulsed resulting in a mobile spleen with medial lie. Ligasure division of the short gastric and splenic arteries and veins was performed and the spleen removed resulting in satisfactory haemostasis. The splenic artery was oversewn and a Blake’s drain was placed in the left subdiaphragmatic space before the abdomen was closed. She received transfusion of six units of red blood cells and two units of fresh frozen plasma in total. The rural hospital did not have an intensive care unit therefore transfer to the nearest unit 100 km away was arranged.

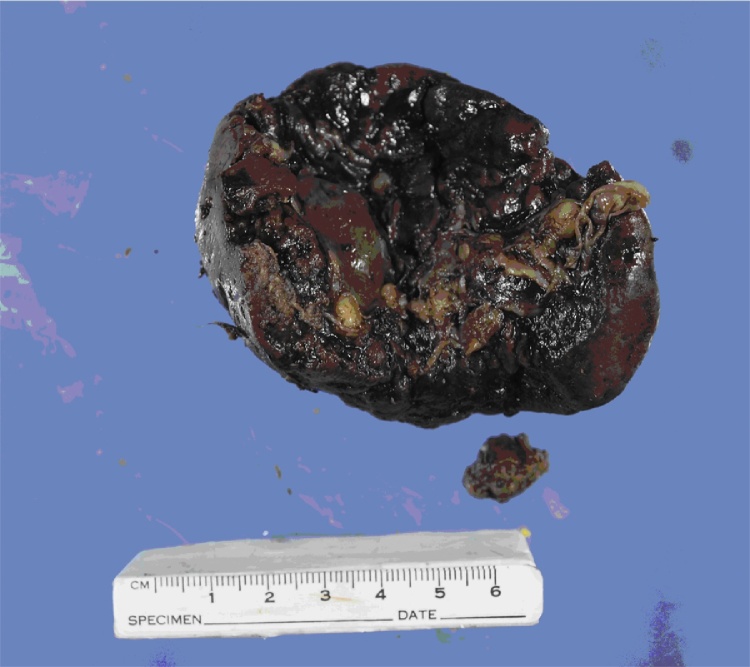

The patient was successfully extubated 48 h later and discharged home on post-operative day four. Investigations for her pneumonia did not reveal a causative organism with negative findings for influenza A and B and RSV direct antigen tests, respiratory virus PCR, sputum microscopy and culture, urinary antigen testing for legionella and pneumococcus and serologic testing for chlamydia, EBV and legionella. Histopathology revealed a 95 g spleen measuring 65 × 60 × 30 mm with a 25 mm defect consistent with possible site of rupture (Fig. 2). Pulp architecture was preserved and there was no evidence of malignancy.

Fig. 2.

The spleen.

On review in the surgical outpatient department two weeks postoperatively the patient described an uncomplicated recovery. Her pneumonia had resolved, her surgical wounds were healing well and she had resumed nearly all activities. Her only complaint was some persisting back pain. She had been immunised against Pneumococcus, Meningococcus and Haemophilus influenza type b by her general practitioner but declined the trivalent influenza vaccine. She had also been commenced on prophylactic amoxicillin and she had been added to the splenectomy register.

3. Discussion

Atraumatic splenic rupture is rare but potentially fatal. The overall incidence remains unclear but there appears to be a male predominance of 2:1 [1]. The median age of occurrence is 45 years. Aetiologies include neoplasia (30%), infectious (27%), inflammatory (20%) treatment related (9%), mechanical (7%) and idiopathic. In about 9% of cases there are two or more aetiological factors [2]. At least 55% of patients have splenomegaly. Of the infectious causes, 40% are attributed to EBV and 17% to Malaria (Plasmodium vivax or falciparum) but there are numerous other organisms that have been implicated [2]. Atraumatic rupture secondary to cough and/or pneumonia is particularly rare, with only 12 reported cases since 1980 [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, Q fever and Legionella have been identified as pathogens.

The exact pathologic mechanisms resulting in rupture have not been firmly established and are likely to be multifactorial involving anatomical, haematological and immunological factors. Intrasplenic tension may be increased by cellular hyperplasia [15]. Ligamentous laxity may predispose to torsion and venous congestion [16]. Pregnancy, cough, emesis and defecation increase intra-abdominal pressure [15] and repeated or prolonged such episodes may result in accumulated trauma to the splenic capsule. Lymphocytic and monocytic infiltration of the splenic capsule may result in fragmentation. Reticular endothelial hyperplasia may predispose to thrombosis, infarction and haemorrhage. Coagulopathy or platelet function may prolong haemorrhage that would otherwise form a haemostatic clot [17].

Patients most commonly present with abdominal pain and signs of shock. Chest pain is another possible presentation [18]. Blood tests should include full blood count, urea, electrolytes and creatinine, liver function tests, cross match and coagulation studies. Diagnosis can be made on CT in haemodynamically stable patients only. Otherwise it may be identified on bedside ultrasonography or intraoperatively [15], [19]. Further investigations depend on the suspected aetiology and may entail a work-up for suspected malignant, infective and/or inflammatory disorders.

No randomised controlled trials have been conducted evaluating the management of atraumatic splenic rupture. In the largest meta-analysis to date, Renzulli et al. found 85% were managed surgically which almost always consisted of total splenectomy. 15% were managed conservatively. Organ preserving surgery was rarely performed and transcatheter arterial embolization was infrequently utilised. Elvy et al. recommended emergency total splenectomy in cases of peritonism, high-grade injury, severe hypovolaemic shock and malignancy while conservative management could be tried in the absence of these features [18]. Renzulli et al. found mortality attributed directly to the splenic rupture was 12%. Note that deaths attributed to other causes within 30 days were excluded from the study which may have underestimated mortality. Long term survival is thought to depend on the underlying pathology [15]. Adverse prognostic factors include splenomegaly and age >40 years.

Diagnosis is often delayed likely due to its rarity resulting in a low index of suspicion. Only 22% will have the diagnosis on admission to hospital [2]. When admitted with another diagnosis, clinical deterioration could be misinterpreted as worsening of that condition (e.g. sepsis secondary to a primary infective process) rather than prompting clinicians to consider an atraumatic splenic rupture. A high index of suspicion and a thorough work-up is essential as a missed or delayed diagnosis increases the risk of mortality [19]. In our case the splenic rupture could not have been anticipated or prevented. The patient was fortunate she ruptured/decompensated as an inpatient and the diagnosis was made quickly which allowed prompt access to emergency surgery.

Local guidelines regarding immunizations and antibiotic prophylaxis post splenectomy should be followed. In Australia this consists of immunization against Pneumococcus, Meningococcus, Haemophilus influenza type b and influenza at least seven days post emergency splenectomy and prophylactic antibiotics for at least three years or lifelong if immunocompromised [20]. Patients should also be provided with an emergency antibiotic supply and education on the identification and possible severe outcomes of bacterial infection. An alert bracelet and registration with the asplenic register is also recommended.

4. Conclusion

Atraumatic splenic rupture is a rare but potentially fatal complication of numerous disease processes including pneumonia. When a patient is deteriorating, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion for alternative aetiologies and perform a thorough, systematic work-up to avoid delayed diagnosis of atraumatic splenic rupture and other uncommon entities and prevent subsequent morbidity and mortality. Post-operative follow-up must address the potential sequelae of asplenia and should include education, immunisations and antibiotic prophylaxis.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contribution

Dr. Guy performed the chart and literature review and wrote the case report with the frequent assistance of Dr. De Clerq.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

This case report was granted approval for exemption from human research ethics committee review by the Chair of the Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee Reference Number HREC/16/QCQ/31.

Funding

This project received no funding.

Guarantor

The guarantor is Dr Stephen Guy.

References

- 1.Renzulli P., Hostettler A., Schoepfer A.M., Gloor B., Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br. J. Surg. 2009;96(10):1114–1121. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renzulli P., Hostettler A., Schoepfer A.M., Gloor B., Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br. J. Surg. 2009;96(10):1114–1121. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salame J., Mojddehian N., Kleiren P., Petein M., Lurquin P., Dediste A. Atraumatic splenic rupture in the course of a pneumonia with Streptococcus pneumoniae: case report and literature review. Acta Chir. Belg. 1993;93(2):49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toubia N.T., Tawk M.M., Potts R.M., Kinasewitz G.T. Cough and spontaneous rupture of a normal spleen. Chest. 2005;128(3):1884–1886. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Citton R., Del Borgo C., Belvisi V., Mastroianni C.M. Pandemic influenza H1N1, legionellosis, splenic rupture, and vascular thrombosis: a dangerous cocktail. J. Postgrad. Med. 2012;58(3):228–229. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.101652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wergowske G.L., Carmody T.J. Splenic rupture from coughing. Arch. Surg. 1983;118(10):1227. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390100089024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domingo P., Rodríguez P., López-Contreras J., Rebasa P., Mota S., Matias-Guiu X. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen associated with pneumonia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996;15(9):733–736. doi: 10.1007/BF01691960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes A.H., Ng V.W., Fogarty P. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in Legionnaires’ disease. Postgrad. Med. J. 1990;66(780):876–877. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.780.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumbach A., Brehm B., Sauer W., Doller G., Hoffmeister H.M. Spontaneous splenic rupture complicating acute Q fever. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1992;87(11):1651–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson S.A., Templeton J.L., Wilkinson A.J. Spontaneous splenic rupture: a unique presentation of Q fever. Ulst. Med. J. 1988;57(2):218–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoenenberger R.A., Weiss P., Ritz R. Spontaneous splenic rupture in Haemophilus influenzae septicemia. Intensive Care Med. 2016;17(3):188. doi: 10.1007/BF01704731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saura P., Valles J., Jubert P., Ormaza J., Segura F. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a patient with legionellosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1993;17(2):298. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casanova-Roman M., Casas J., Sanchez-Porto A., Nacle B. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen associated with Legionella pneumonia. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2010;21(3):e107–e108. doi: 10.1155/2010/846419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Athey R., Barton L., Horgan L., Wood B. Spontaneous splenic rupture in a patient with pneumonia and sepsis. Acute Med. 2005;5(1):21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gedik E., Girgin S., Aldemir M., Keles C., Tuncer M.C., Aktas A. Non-traumatic splenic rupture: report of seven cases and review of the literature. W. J. Gastroenterol. 2008;14(43):6711–6716. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhury A.K. Spontaneous rupture of a normal spleen. Injury. 2004;35(3):325–326. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(03)00238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tataria M., Dicker R.A., Melcher M., Spain D.A., Brundage S.I. Spontaneous splenic rupture: the masquerade of minor trauma. J. Trauma-Inj. Infect Crit. Care. 2005;59(5):1228–1230. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196439.77828.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elvy A., Harbach L., Bhangu A. Atraumatic splenic rupture: a 6-year case series. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2010;18(2):124–126. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32833ddeb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kocael P.C., Simsek O., Bilgin I.A., Tutar O., Saribeyoglu K., Pekmezci S. Characteristics of patients with spontaneous splenic rupture. Int. Surg. 2014;99(6):714–718. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00143.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Recommendations Spleen Registry: Spleen Australia (2015) Available from: https://spleen.org.au/VSR/Files/RECOMMENDATIONS_Spleen_Registry.pdf.