Highlights

-

•

Grand proportions fyssural cyst enucleated with Le Fort I osteotomy and down-fracture.

-

•

The remaining space was filled with BIOSs and bioguide (lyophilized bone and collagen membrane).

-

•

Patient’s follow-up presents no recurrence and favorable osseous formation.

Keywords: Non-odontogenic cysts, Osteotomy, Le Fort, Maxillofacial abnormalities, Case report

Abstract

Fissural cysts (FC) are caused by entraped epithelium between nasal and maxilar processes. They are commonly treated with surgical enucleation precedded or not by marsupialization depending on the cyst size. Biopsy of lesion is recommended due to confirm radiographic evaluation. It is rare to observe Le Fort I surgical approach to this type of injury. This study reports the case of an uncommon grand proportions fissural cyst in a female patient, 53, that was referred to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Departament of Hospital XV presenting volume increase in maxilla associated with numbness of palate. Radiograph examination showed an intimate relationship between incisors apexes and FC. Expansion of both buccal and palate cortical was then confirmed as well as its unusual size, approximately 25 millimeters. Due to the abnormal size of lesion and possible impairment of upper incisors, LeFort I osteotomy associated with downfracture to cystic enucleation was the chosen treatment. After enucleation, the remaining space was filled with BIOSs and bioguide (lyophilized bone and collagen membrane). Patients’ twelve months follow-up demonstrate no relapses and maintenance of teeth involved.

1. Introduction

Fissural cyst manifests as a painless, circular or ovoid lesion, producing a fluctuant, symmetrical swelling along the midline of the palate. Usually asymptomatic, pain may develop when the nasopalatine nerve is irritated by local extension, or when the cyst becomes secondarily infected. When it does not present painful symptoms is generally discovered incidentally during routine dental or radiologic examination. Pathogenesis is controversial, relying in the activation and proliferation of epithelium remnants between nasal and maxillary processes, which fuse to form hard palate during the sixth fetal week. Elliott et al., 2004, investigated in 2162 skull, searching for predilection race, which could not be determined [1]. Signs and symptoms include swelling of the anterior palate, drainage, pain and swelling in the lip [2], [3]. However, many lesions are asymptomatic, identified by routine panoramic radiography. FC imaging appears as a well-circumscribed radiolucent lesion close to the median line. Root reabsorption is rarely noticed. Injury is usually round or oval, with a sclerotic margin.

As the lesion is benign, it is usually managed intraorally by enucleation, followed by closure. Marsupialization might be an associated with treatment depending on the lesion size. Biopsy is recommended due to confirm radiographic evaluation [2]. Suggested treatment consists in total enucleation [4], preceded or not by marsupialization [1].

Le Fort I osteotomy is a procedure develop by René LeFort mainly used to correct maxillary and craniofacial deformities [6]. Also known as a horizontal maxillary osteotomy, the fracture or surgical cut occurs at the base of the upper jaw above apices of teeth roots [7]. The first time Le Fort I approach was described to treat nasopharyngeal tumors was in 1857. It was also described to access pituitary fossa as well as to treat pathological conditions in maxilla. As a surgical approach for tumors removal of the midface, skullbase as well as nasopharynx, is part of a global concept of surgical approaches without a visible and no aesthetic incision on the facial skin. Literature suggests use Le Fort I osteotomy when pathologies are situated in maxillary sinus, sphenoid sinus or nasopharynx providing a direct view of those regions. Le Fort I osteotomy i salso used to treat benign neoplasms, semi-malignant as well as malignant neoplasms depending on its localization and extension [7], [16], [17].

This study aims to present a FC case, diagnosed by clinical, radiographic and histopathologic findings which was assessed by Le Fort I osteotomy, comnonly used to treat dento-facial deformities. It is rare to use this access to treat this lesion type. Le fort I osteotomy was chosen due to the FCs’ size and location.

2. Presentation of case

This case report was described according to the SCARE Statement [8]. White Female patient, 53 years-old, attended to the Surgery Department of Oral and Maxillofacial, reporting volume increase in maxilla associated with numbness of palate. It was referred to the maxillo-facial service after dental work with another dentist that reported the lesion after analysing panoramic radiography. Patient informed that the volume increase did not disturb it daily activities. Clinical examination revelled significant swelling in palate. Cortical expansion was associated with volume increase in anterior maxilla, mainly perceptible in palatine cortex (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

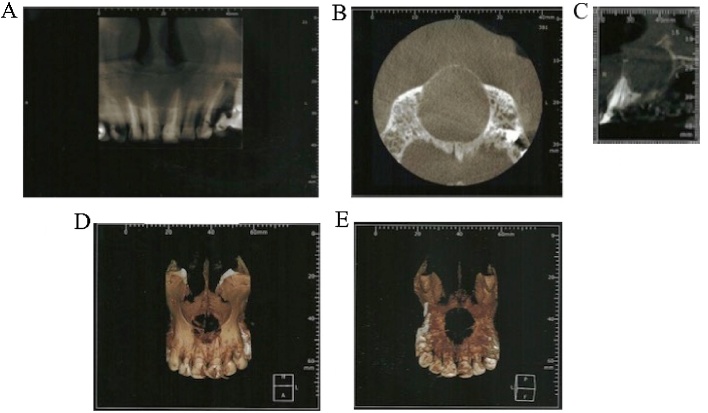

Fig. 1.

A) panoramic radiograph evidenced intimate relationship between central incisors apexes as well as mesial region of lateral incisors. Anterior tooth were endodontically treated maybe on the first analysis, because of intimate relationship between anterior tooth apexes, it was though to be an endodontic-related lesion. No canine relationship was observed. B) tomographic analysis showed cortical expansion, a well-delimited lesion with an intimate relationship between incisors apexes. Buccal cortex was found to be delicate and it was thought that might be a perforation of nasal floor. No root reabsorption was evidenced. C) Tomography was taken to evidence relationship between central incisors as well as mesial region of lateral incisors. D) Figure shows involvement of maxilla and central region of maxilla and buccal cortex. E) Figure shows relationship between the lesion and palate.

Intraoral examination revealed a well-defined oval-shaped lesion located posterior to palatine papilla in the m iddle line. Imaging showed an oval lesion in intimate relationship with incisors apexes as well as cortical expansion. Buccal cortex was found to be delicate and it was associated with a nasal floor perforation. No root reabsorption was evidenced. Anterior tooth were endodontically treated due to its intimate relationship with the lesion, and because it was firstly thougth to be an endodontic-related lesion (Fig. 4).

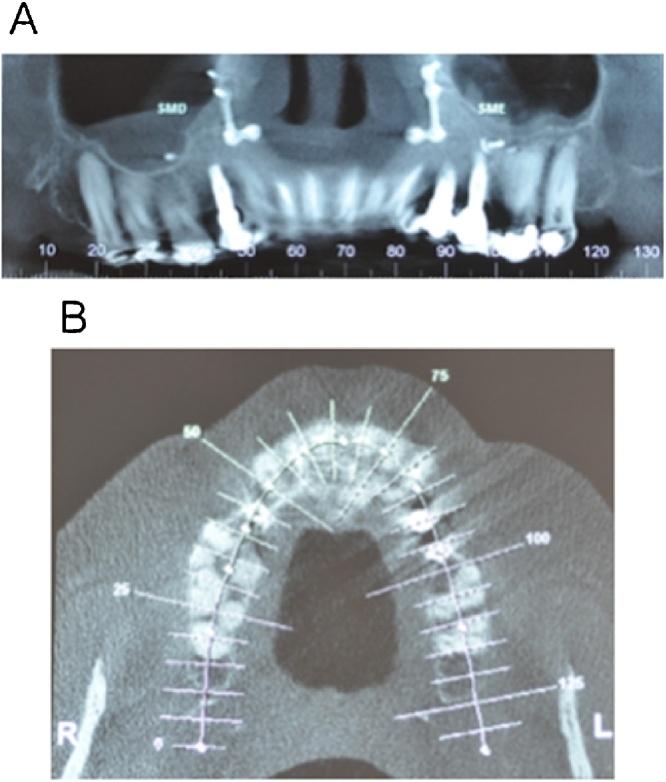

Fig. 4.

A and B) imaging showing no relapses of the lesion. After 12 months, patient is stable, without functional or aesthetic complaints.

Cone-Beam tomography was conducted to evidence relationship between central incisors as well as mesial region of lateral incisors. No canine relationship was observed. As patient had installed an implant, tomography was also conducted to analyze a possible influence in development of lesion. No signs were observed. Lesion involved central incisors and appeared to abut mesial surface of lateral incisors. Expasion of both buccal and palate cortical was then confirmed as well as its unusual size, approximately 25 millimeters.

Due to its specific anatomic localization differential diagnosis lead clinicians and surgeons to relate to a limited number of diagnostic hypothesis. Lesions sized until 2 or 4 mm radiograficaly might be difficult to differentiate to increased anterior palatine foramen and so clinical information (pain, dental displacement) as well as imaging (increased size of lesions) are crucial in diagnostic process. The main differential diagnosis usually suggested include nasopalatin duct cyst, periapical cyst placed apical or laterally to dental roots and keratocist odontogenic tumour.

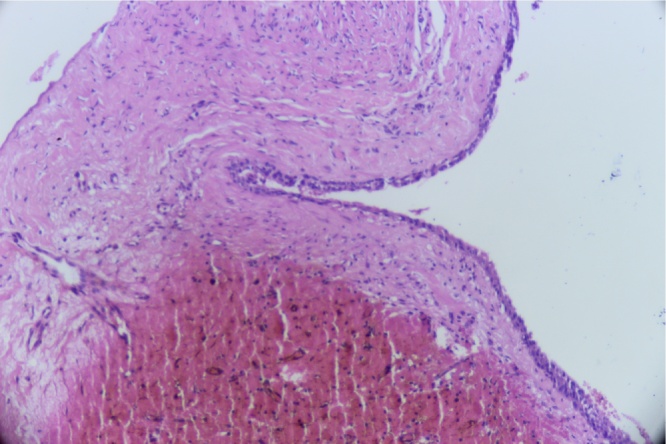

Incisional biopsy under local anesthesia was the first step chosen to define surgical treatment. Material removed underwent histological analysis and confirmed FC diagnose. Hematoxilin-eosin histological examination demonstrated a cyst composed of minor salivary glands, arteries, vessels, and nerves. Pseudo stratified and cuboidal epithelium was also found. Due to histological findings, the chosen surgical treatment was total enucleation trough Le Fort I osteotomy. The procedure was conducted by a sênior surgeon.

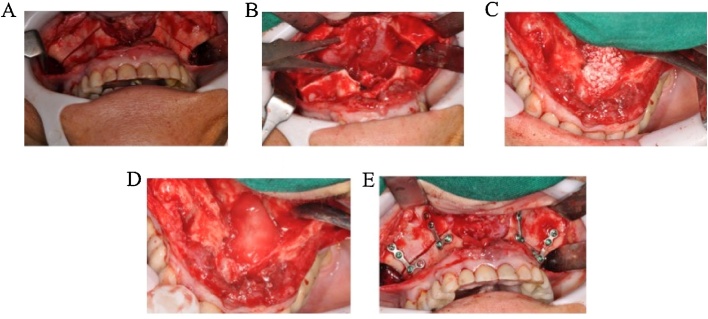

Labial approach was conducted to access region of interest. After incision, tissues and periosteum were separate from bone using Molt retractors. Bone osteotomy was preferably designed on lateral region of nasal cavity and continued until zygomatic pilar. Nasal cavity was disengaged from maxilla to expose FC, achieved by using Smith retractors in both sides of maxilla. Lesion was clinically well delimited in intimate relationship with central and lateral incisors apexes and no perforation of nasal floor as well as maxillar sinus was observed. After enucleation, the remaining space was filled with BIOSs and bioguide in order to accelerate bone formation. In order to correct occlusion, osteotomy was designed and plates and screws were positioned. Subsequently, plates were removed and maxilla downfracture was conducted. After cystic enuclation, maxilla was placed in the same predetermined location. Removed material was also sent for histological analysis. After 12 months, patient is stable, without functional or aesthetic complaints.

3. Discussion

By definition, a fissural cyst is described by a pathological cavity revested by epithelium. Independent of its origin, fissural cysts can develp in any oral and maxillofacial region, and in a wide age range [9], [19], [11], [12]. Pathogenesis is not clear, but it is believed that they emerge from epithelium remnants trapped between maxilary processes of maxila as well as nasal process—communication between nasal cavity and anterior maxilla in fetus development—that might develop from trauma of infection [14]. As fetal development continues, this connection gradually narrows as bones from anterior palate region fuse. In a high proportion of cases, complete bone regenarition was noted within 3 years without bone grafting. For unknown reasons, those remnants activate and proliferates later to develop into a cystic lesion.

Clinically, this pathology may appear as tumefaction in the oral and maxillofacial anterior region associated with slow development and no symptomatology that can be foundt in routine radiographic examinations during dental treatment [3]. It might be associated as well with palate and superior lip edema, dental extrusion, oval radiographic image with radiolucent area well limited, quite next to anterior palatin raphe. Those cinical features meet patterns cited in this study. Literature suggests that the cyst can achieve considerable sizes and subsequent complications, such as perforation of nasal cavity and maxillary sinus during surgery [13].

FC epithelium is variable, and it can be formed by squamous epithelium, colunar pseudostratified, colunar and cubic [2]. Presence of blood vessels, nerves and glandular structures in its walls, similar to minor salivary glands has been also reported in literature. Literature also suggests that degeneration of those structures as a result of chronic inflammation around cyst walls [13].

Small cysts in early stages of development are frequently asymptomatic and usually present asymptomatic palatal swellings. They may rarely be accompanied by pain and/or purulent discharge. Pain complaint might be related to adjacent structures compression particularly above affected region or associated with dentures use where there is compression [15]. The more caudal the cyst, it is suggested that the earlier symptoms appear. Normally symptoms manifest as inflammatory process (46% of cases) that rarely develops to facial asymmetry once lesion development is intraoral (palatine) [11]. Hyalinization could be interpreted as a degenerative phenomenon and is presumably mainly the result of a pre-existing inflammatory reaction and/or the effect of pressure upon tissues around cyst walls. Some cases may cause pain and itches. Rarely generates a complete floating lesion evolving anterior palate and alveolar mucosa region [2].

Treatment according to literature is based on surgical removal, followed or not by marsupialization, depending oh the size of FC. Gosal et al. (2010) suggested that all cases might be surgical enucleated as soon as possible, since recurrence is approximately 11–30%. Biopsy is mandatory because FC is not diagnosed radiographically. The patient reported on this study is being monitored and shows no relapses after treatment.

Le fort I osteotomy, as a surgical approach for removal of tumors of midface, skull base and the nasopharynx, is part of a more global concept of surgical approaches without a visible incision on the facial skin. This approach provides a direct view of both maxillary sinus and nasal cavity [16]. Osteotomy is performed in the lateral wall of maxilla sinus that can be adapted to location of tumour. Osteotomies situated higher below infraorbital foramen allow a direct view of orbital floor [17]. It was described as a single access for exposing medial compartiment of inferior skull base from tuberculum sellae to the foramem magnum, aiming to execute neurosurgical procedures (pharyngotomy, clivectomy and dural opening [18].

Safety in executing this procedure was demonstrate by Wood and Stell, in 1989, when five cases of skull base tumors were removed [19]. They reported absence of facial scars, relatively simple access and wide exposure of the area of interest. Another advantage is facilitation to ensuing reconstructive procedures. According to Salier et al., 1999, it provides an excellent access to mobilize and fix buccal fat pad to the medial aspect of the defect following maxilla resection. Adaptation of bone grafts in the defects as well as fixation of dental implants can be done through the same incision [20].

Hermann et al., 1999, analysed efficacy and versatility of Le Fort I approach by surgically removal of 17 midface tumors between benign neoplasms (osteoblastoma, osteoma, ossifying fibroma, aneurysmal bone cyst), semi-malignant (ameloblastoma, myxoma) and malignant neoplasms (metastasis, anesthesioneuroblastoma, lymphoepithelial carcninoma). Most of them were limited to maxillary sinus and its walls, including maxillary alveolar process. They suggests that this approach is reliable and gives excellent access. Furthermore, it provides wide exposure and clear vision of resection margins, absence of visible scars, feasibility of combining this approach with reconstruction, insertion of endosseous implants or other prothestetics procedures via the same incision via the same incision.

Steinhauser (1998) suggested that Le Fort I osteotomy must not be limited to benign tumors removal, but to resection borders tumors and additional cranial lateral and central approaches can be used if necessary [21]. Transfacial incisors and approaches were strongly suggested to be reserved for underlying malignancies which have invaded facial soft tissues.

After Le Fort I approach to enucleation of large proportions FC, patients’ follow-up showed no relapses and positive bone regeneration after surgery.

4. Conclusion

Clinical relevance of this study remains on the surgical approach performed, which is different of articles cited. No specific etiological factor was found but pathological process in adjacent tissue may be potential stimuli. Also the size of fissural cysts does not show any correlation to the symptoms. We categorically advice to enucleate it at an early stage of development in order to minimize pre- and post-operative risks as far as possible. Patient’s follow-up presents no recurrence and favorable osseous formation.

Regarding conflicts of interest, the authors Rafael Correia Cavalcante, Fernanda Durski, Tatiana Miranda Deliberador, Allan Fernando Giovanini, Nelson Luis Barbosa Rebellato, Delson João da Costa, Leandro Eduardo Kluppel, Rafaela Scariot have no conflicts to declare.

Ethical approval was not needed on this study because the patient consent to film, take pictures as well as publish the case report contributing to scientific knowledge. Authors confirm that a consent was signed up by the patient. Consent form will be sent attached to this file.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Ethical approval was not needed on this study because the patient consent to film, take pictures as well as publish the case report contributing to scientific knowledge. Authors confirm that a consent was signed up by the patient. Consent form will be sent attached to this file.

Authors contribution

1) Rafael Correia Cavalcante: study concept, case report design, translation to English and critical appraisal;

2) Fernanda Durski: patient follow-up and study concept;

3) Tatiana Miranda Deliberador: contributed to surgical techniques and procedures;

4) Allan Fernando Giovanini: pathological analysis;

5) Nelson Luis Barbosa Rebellato: research design and critical appraisal;

6) Delson João da Costa: research design and critical appraisal;

7) Leandro Eduardo Kluppel: contributed to surgical techniques and procedures;

8) Rafaela Scariot: study concept, case report design, critical appraisal, contributed to surgical techniques and procedures, corresponding author.

Ethical approval

No nedded due to the fact that it is a case report. We only nedded the patient’s consent.

Consent

The authors of this paper confirm that consent was signed up by the patient authorizing to film, to take photographs as well as report the case to contribute to scientific knowledge.

Guarantor

Finally, the guarantors of the case report is Rafaela Scariot and Rafael Correia Cavalcante who are fully responsible for the work and conduction of the study. They have access to all data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Fig. 2.

histopathological analysis. At the miscroscopic observation, the examination of hematoxylin and eosin stained revealed fragment of cystic capsule, composed of dense and vascularized connective tissue with hemorrhagic foci. In contiguity in the lumen it was observed a coating of non-keratinized squamous stratified epithelium, composed of 3–4 layers of cells, compatible with de diagnosis of fissural cyst. (original magnification 100×).

Fig. 3.

A) Labial approach was used to access region of interest. After incision, tissues and periosteum were separate from bone using molt retractors. Bone osteotomy was preferably designed on lateral region of nasal cavity. B) Nasal cavity was disengaged from maxilla to expose FC. Separation of maxilla was conducted using Smith retractors to expose the lesion. Lesion was well delimited in intimate relationship with central and lateral incisors apexes. C) After enucleation, the remaining space was filled with BIOSs and bioguide. It was applied in all walls of the lesion to accelerate. D) Lesion was well delimited in intimate relationship with central and lateral incisors apexes. E) In order to correct occlusion, osteotomy was designed and plates and screws positioned. Subsequently, plates were removed and maxilla downfracture was conducted. Later cystic enuclation, maxilla was placed in the same predetermined location. Removed material was also sent for histological analysis.

Contributor Information

Rafael Correia Cavalcante, Email: rafaelcorreia14@gmail.com, Rafaela_scariot@yahoo.com.br.

Fernanda Durski, Email: durskifernanda@yahoo.com.br.

Tatiana Miranda Deliberador, Email: tdeliberador@gmail.com.

Allan Fernando Giovanini, Email: afgiovanini@gmail.com.

Nelson Luís Barbosa Rebellato, Email: rebelato@ufpr.br.

Delson João da Costa, Email: d.j.c@uol.com.br.

Leandro Eduardo Klüppel, Email: lekluppel@hotmail.com.

Rafaela Scariot, Email: Rafaela_scariot@yahoo.com.br.

References

- 1.Elliot K., Franzese C., Pitman K. Diagnosis and surgical management of nasopalatine duct cysts. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(August (8)):1336–1340. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neville B. 4th ed. vol. 1. Guanabara Koogan; 2016. (Patologia Oral E Maximo-Facial). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveira P.R., Enoki A.M., I, Pizarro G.U., I, Morais M.S., Fernandes D. Nasolabial bilateral cyst as cause of the nasal obstruction: case report and literature review. Arq. Int. Otorrinolaringol. 2012;16(February):224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedin M., Klanfeldt A., Persson G. Surgical treatment of nasopalatine duct cysts: a follow-up study. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1978;1(February):427–433. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(78)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obwegeser H. Orthognathic surgery and a tale of how three procedures came to be: a letter to the next generations of surgeons. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2007;34(February (3)):331–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2007.05.014. (8232) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fort Le., I . 1st ed. vol. 1. Houghton Mifflin Co; 1995. (Stedman’s Medical Dictionary). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R., Fowler A., Saetta A., Barai I., Rammohan S., Orgill D. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. (article in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachur A., Santos T., Silveira H., Pires F. Cisto do ducto nasopalatino: considerações microscópicas e de diagnóstico diferencial. Robrac. 2009;18(February (47)):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escoda-Francoli J., Almendros-Marques N., Becini-Aytes L. Nasopalatine duct cyst: report of 22 cases and review of the literature. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2008;12(March (1)):438–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Igreja F. Marsupialização como tratamento inicial de cisto do ducto nasopalatino. Rev. Cir. Traumatol. Buco-Maxilo-Fa. 2005;5(April (2)):41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosau M., Draener F., Frrerich B. Two modifications in the treatment of keratocystic odontogenic tumors and the use of Carnoy’s solution—a retrospective study lasting between 2 and 10 years. Clin. Oral Invest. 2010;(June):14–24. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allard R., van der Wall W., van der Kwast W. Nasopalatine duct cyst. Review of the literature and report of 22 cases. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1981;10(February):447–461. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(81)80081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandor G., Charles V., Lawson C.Tator. Trans oral approach to the nasopharynx and clivus using the Le Fort I osteotomy with midpalatal split. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1990;19(March):352–355. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grime P.D., Haskell I., Robertson R. Gullan Transfacial access for neurosurgical procedures: an extended role for the maxillofacial surgeon I. The upper cervical spine and elivus. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1991;10(March):285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Loveren H., Fernandez P., Keller J. Neurosurgical applications of le fort I-type osteotomy. Clin. Neuro-Surg. 1994;41(July):425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood G., Stell P. Osteotomy at the Le Fort I level. A versatile procedure. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1989;27(June):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(89)90124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sailer H., Haters P., Grate K. The Le Fort I osteotomy as a surgical approach for removal of tumours of the midface. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 1999;27(January (1)):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(99)80002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinhiiuser E.W. Historical development of orthognathic surgery. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 1998;24(January):195–204. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(96)80002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermann F.S., Piet E.H., Klaus W.G. The Le Fort I osteotomy as a surgical approach for removal of tumours of the midface. J. Craniofac.-Maxillofac. Surg. 1999;27(February (1)):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(99)80002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]