Abstract

Medicare Advantage: Issues, Insights, and Implications for the Future

Paul Cotton, Joseph P. Newhouse, PhD, Kevin G. Volpp, MD, PhD, A. Mark Fendrick, MD, Susan Lynne Oesterle, Pat Oungpasuk, Ruchi Aggarwal, Gail Wilensky, PhD, and Kathleen Sebelius

Editorial S-2

D.B. Nash, and A.Y. Schwartz

The History, Impact, and Future of the Medicare Advantage Star Ratings System S-3

P. Cotton

Medicare Advantage and Traditional Fee-For-Service Medicare S-4

J.P. Newhouse

Behavioral Economics: Key to Effective Care Management Programs for Patients, Payers, and Providers S-5

K.G. Volpp

Value-Based Insurance Design: A Promising Strategy for Medicare Advantage S-6

A.M. Fendrick, S.L. Oesterle, P. Oungpasuk, and R. Aggarwal

Two Perspectives on the Future of Medicare Advantage S-7

G. Wilensky and K. Sebelius

Population Health Management publishes supplements that (a) discuss new technologies, theories, and/or practice, and (b) serve as enduring materials to disseminate information from conferences and special meetings. Supplements that discuss new technologies, theories, and/or practices are subject to peer review.

Acknowledgment.

The Better Medicare Alliance provided funding support to the Jefferson College of Population Health to produce this special supplement. The content and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors.

Conflict of interest.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest: Dr. Nash is employed by the Jefferson College of Population Health, which was compensated by the Better Medicare Alliance to produce this supplement. Ms. Schwartz is employed by the Better Medicare Alliance. Dr. Newhouse is a director and holds equity in Aetna, which sells Medicare Advantage plans. Mr. Cotton, Drs. Volpp, Fendrick, and Wilensky, and Ms. Oesterle, Ms. Oungpasuk, Ms. Aggarwal, and Ms. Sebelius declared no conflicts of interest.

Editorial

David B. Nash, Allyson Y. Schwartz

July 30, 2015 was the 50th anniversary of Medicare. During those 50 years, American seniors and individuals with disabilities eligible for Medicare have come to count on Medicare for health care coverage and financial security. Understood to be one of our nation's most successful initiatives, it is viewed as stable and secure, unchanged, and guaranteed to all seniors. Yet, Medicare has been significantly expanded and modified over the decades to meet the needs of its population. These changes have expanded coverage, impacted beneficiary costs, and directed reimbursements for providers. With the passage of the Patient Protection & Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), and the more recent Medicare Access and CHIP Authorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), policy makers are moving to reform the Traditional Fee-For-Service Medicare payment structure to reward value rather than the volume of care by means of bundled payments, accountable care organizations, and incentives for alternative payment models. Medicare Advantage (MA) is leading the way in this transformation away from volume-based care toward a framework of care that aligns incentives that focus on improving health status.

For roughly 40 years, Medicare beneficiaries have had the choice to receive their Medicare benefits from a private health plan instead of through Traditional Fee-For-Service Medicare. In the years since its inception, the program, also known at Part C and formerly known as Medicare+Choice, has undergone multiple updates, including major policy changes passed in 2010 as part of the ACA. Since the passage of the ACA, MA payment is updated each year based on fee-for-service spending at the county level. The per member per month payments to MA plans are also risk adjusted using a complex model that accounts for demographic, health status, income, and other variables. Risk adjustment is critical to MA; it facilitates early diagnosis and prevention, ensures that appropriate resources are available to care for the most complex patients, and prevents preferential selection. MA includes quality bonuses based on plan performance in the MA Star Rating system, as well as an out-of-pocket maximum, neither of which are included in Traditional Medicare. Today roughly 70% of MA enrollees are in high-quality MA plans rated 4+ stars (on a 5-star scale), up from 2012 when enrollment in 4+ star-rated plans was close to 30%.

There are other important distinctions between Traditional Medicare and MA. The Traditional Medicare structure is built around an acute care model that achieves suboptimal outcomes whereas MA is structured to identify health issues early, enable beneficiaries to live with chronic illness, and support providers who offer a full range of coordinated services. MA also has an emphasis on transparency, accountability, and innovation.

Today, our nation faces major challenges in Medicare. First, there is the reality of the near doubling of the number of older adults in the next decade, with 10,000 more individuals turning 65 each day. Second, many of these seniors will live longer and many more will live with multiple serious chronic conditions. There are fiscal implications as the federal government seeks to meet the expectations of these almost 75 million beneficiaries by 2026, as they, their families, and their communities struggle with cost sharing and gaps in coverage.

Health care delivery and financing in America must respond to these changes. The good news is that Medicare, and particularly MA, the part of Medicare that offers a capitated, managed care option for beneficiaries, is actively engaged in delivering patient-centered, high-value care. Evidence shows that MA is achieving the improved outcomes for seniors. Providers—doctors, nurses, hospitals—are changing the way they deliver care to focus on primary care, early intervention, care coordination, and the socioeconomic determinants of health.

This impact is amplified as more beneficiaries choose MA – the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reports that enrollment in MA is expected to reach 18.5 million in 2017, representing 32% of Medicare beneficiaries. Plans and providers report their interest in working to engage beneficiaries in their own health and to help them navigate the complex array of services and care decisions to ensure the best outcomes. We are excited by the fact that MA offers seniors a managed care option with the capacity to tailor care for patients with complex health and social needs. It is offering innovative solutions through new community partnerships, team approaches to care coordination for individuals with serious chronic conditions, attention to care transitions, home-based care, and new financing models between payors and practitioners that incentivize new, effective ways of providing care.

As we approach the upcoming transition, with a new President, new Administration and a new Congress, we call on policy makers to build on the groundbreaking work of MA. MA intersects with the tenets of population health in a number of ways. First and foremost, MA concentrates on prevention, wellness, and upstream health benefits. It focuses health care delivery on coordinating care to slow disease progression, improve outcomes, and redirect health care dollars to meet patients' needs, including vitally important social determinants of health. Importantly, MA offers seniors and individuals with disabilities a managed care option that is transparent and accountable. We are hopeful that policy makers will take the lessons learned and do all they can to promote better, smarter health care for seniors—and all Americans.

This supplement offers the perspectives of experts, researchers, and administrators on MA today and the important role it can play in Medicare for years to come. We hope you find it useful and interesting.

The History, Impact, and Future of the Medicare Advantage Star Ratings System

Policy shifts in the early 2000s resulted in Medicare Advantage (MA) payment rates that were estimated to be 14% higher per enrollee than the cost of covering Medicare beneficiaries under Traditional Fee-For-Service Medicare (TM).1 In terms of total dollars spent, MA cost the government $14 billion more than TM in 2009 alone.2 In addition, though MA Star Ratings were launched in 2008, at the time some MA plan sponsors told the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) that it was difficult to implement quality changes without aligned incentives. As a result, little change occurred in performance levels from 2008 to 2012.

The Patient Protection & Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) sought to bring MA plan payments closer to the payments for TM over time by means of a gradual reduction in payments. The ACA also aimed to improve quality by providing bonus payments to MA plans based on achieving high scores in the Star Ratings system. Despite critics' warnings that these actions would decimate the MA program,3 evidence shows the changes have had their intended impact and the program is thriving.

Since the ACA, MA enrollment has grown steadily and now is rising at a faster rate than overall Medicare enrollment, from 10.9 million in 2009 to a projected 18.5 million in 2017 (ie, 24% to 32% of all Medicare enrollees).4,5 This represents a 57.8% increase in covered lives in MA and nearly 10 million more enrollees in MA than the Congressional Budget Office projected just after the ACA's enactment.

Total MA payment has dropped to 2% above TM costs in 2016, a difference that is related primarily to quality bonuses and rebates.6 Also, MA plan premiums have fallen by nearly 13% since 2010.5 In 2016, as migration continued to highly rated plans with lower cost sharing and additional benefits, the average premium paid by an MA enrollee decreased by $0.31 from 2015.7 According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), 59% of enrollees had no premium hike in 2016.7

Perhaps more importantly, the percentage of highly-rated 4- and 5-Star plans increased from 31% in 2010 to 49% in 2017.8 The percentage of beneficiaries enrolled in highly-rated plans rose even more, from 31% in 2012 to 68% in 2017.8

These positive effects were realized because the ACA provided clear guidance and strong incentives for MA plans to improve. MA plan sponsors have hired new staff with titles such as “Medicare Stars Director” to focus specifically on improving MA Star Ratings scores. Conferences dedicated to this win-win challenge are common across the country. Real people – the nearly one third of the Medicare population now in MA plans – are getting the higher quality health care they deserve. More importantly, the potential for further improvement is vast, as emerging measures will take on high-priority issues such as care coordination and behavioral health.

Today, linking MA Star Ratings to performance-based pay appears to be a critical element in the shift from volume-driven fee-for-service incentives to value-based plans that reward clinicians on the basis of how well they meet the Triple Aim of providing high-quality, efficient, patient-centered care. Performance-based pay is being applied across all parts of Medicare, most state Medicaid, and other health programs, as well as most commercial insurers.

How the Medicare Advantage Star Ratings System and Payment Policies Work.

Medicare first implemented the Medicare Advantage Star Ratings system in 2008, based on:

• Clinical quality measures, such as those in NCQA's Healthcare Effectiveness Data & Information Set;

• Patient experience-of-care measures in the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems;

• Patient-reported outcomes measures in the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey9 of randomly selected Medicare enrollees;

• Medicare administrative measures on issues such as appeals and complaints.

Medicare updates measures each year to remove any that “top out” with little room for further improvement, and adjusts specifications for changes in underlying clinical evidence.

Measure weights vary by type: structure and process measures (eg, preventive screenings) have weights of 1; patient experience measures (eg, access to care) have weights of 1.5; outcome measures (eg, readmission rates) and intermediate outcomes (eg, high blood pressure control) have weights of 3. A measure of overall plan improvement has a weight of 5.

The measures address both Medicare Advantage (Part C) medical service coverage and prescription drug coverage (Part D). They are grouped into 9 domains:

1. Staying Healthy: screenings, tests, and vaccines

2. Managing Chronic (Long-Term) Conditions

3. Member Experience with Health Plan

4. Member Complaints and Changes in Health Plan Performance

5. Health Plan Customer Service

6. Drug Plan Customer Service

7. Member Complaints and Changes in the Drug Plan's Performance

8. Member Experience with the Drug Plan

9. Drug Safety and Accuracy of Drug Pricing

Medicare calculates results for each measure, each domain, and then an overall score, and publicly reports the results on the MA Plan Finder10 to help inform beneficiaries' choices. Results also determine plan bonuses and rebates: MA plans with Star Ratings of 4, 4.5, or 5 receive bonuses equal to 5% of the county-level benchmark rate. MA plans may use bonuses to lower premiums and/or cost sharing, or to provide additional benefits, all of which attract enrollees to higher rated plans.

Plans receive rebates if the bid price they propose for covering their enrollees is below the benchmark. Rebates rise with Star Ratings.

• Plans with 4.5–5 Stars get 70% of the difference between the benchmark and their bid price

• Plans with 3.5–4.5 stars get 65%

• Plans with <3.5 Stars get 50%

Medicare requires plans to use rebates to lower premiums/ cost sharing or provide additional benefits.

The highest-rated 5-Star plans are further rewarded with the ability to enroll new members outside of the Fall open enrollment period – another way to boost enrollment in the highest quality plans.

The ACA also penalizes poor performers – plans with less than 3 Stars for 3 or more years. Medicare sends letters to enrollees in these plans encouraging them to shop for alternative coverage, places an icon on Plan Finder to warn potential enrollees, and prohibits enrollment through the Plan Finder.

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March 2009. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/march-2009-report-to-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=0 Accessed October18, 2016

- 2.The CMS Blog. Affordable Care Act has strengthened Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug Program. September 22, 2016. https://blog.cms.gov/2016/09/22/affordable-care-act-has-strengthened-medicare-advantage-and-prescription-drug-program/ Accessed October18, 2016

- 3.Book RA, Capretta JC. Reductions in Medicare Advantage Payments: the impact on seniors by region. September 14, 2010. http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2010/09/reductions-in-medicare-advantage-payments-the-impact-on-seniors-by-region Accessed October10, 2016

- 4.Congressional Budget Office (CBO). CBO's August 2010 Baseline: Medicare. August 2010. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/51302-2010-08-Medicare.pdf Accessed October10, 2016

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Fact Sheet: Moving Medicare Advantage and Part D Forward. September 22, 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-09-22.html Accessed October18, 2016

- 6.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. March 2016 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Chapter 12: The Medicare Advantage program: Status report. March 2016. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-12-the-medicare-advantage-program-status-report-march-2016-report-.pdf?sfvrsn=0 Accessed October18, 2016

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Press Release: Medicare Advantage Premiums Remain Stable; Enrollment at All-Time High. September 21, 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2015-Press-releases-items/2015-09-21.html Accessed October18, 2016

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2017 Star Ratings. October 12, 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-10-12.html Accessed October18, 2016

- 9.Medicare.gov Medicare Plan Finder. https://www.medicare.gov/find-a-plan/questions/home.aspx Accessed September15, 2016

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. http://www.hosonline.org/ Accessed September15, 2016

Medicare Advantage and Traditional Fee-For-Service Medicare

Joseph P. Newhouse, John D. MacArthur

For the past several years I have led a group carrying out research comparing Medicare Advantage (MA) and Traditional Fee-For-Service Medicare (TM). Many of our findings are summarized in 2 publications1,2; the following is a brief summary of conclusions from these papers and a discussion of some related issues.

Conclusion: MA delivers the same core Medicare benefits as TM at a lower cost. However, the budgetary cost of MA is higher than TM because Congress legislated additional MA quality bonus payments in exchange for additional benefits to MA beneficiaries.

MA plans bid against a benchmark based on average TM spending per county to provide the same covered services as TM. MA plans also must design cost sharing that does not exceed the annual MA out-of-pocket maximum, which was $6700 in 2016. TM does not have an out-of-pocket maximum. For 2016, MA plan bids for a standardized beneficiary were 94% of TM costs.3 For health maintenance organization (HMO) MA plans, the bids were 90% of TM costs.3 However, Medicare paid MA plans 102% of TM costs, with the 8 percentage point difference (8 = 102-94) going to beneficiaries in the form of lower premiums, lower cost sharing, additional covered services such as dental, or some combination of the 3.

Conclusion: For methodological and data availability reasons, quality of care is difficult to compare between MA and TM; however, limited comparisons tend to favor MA.

We compared emergency department (ED) and hospital use in MA HMOs with a sample of TM beneficiaries matched on age, sex, race, and zip code in 2003 and again in 2009. ED use by the MA group was 25%-35% less, and hospital days were about 20%-25% less, than the TM group. Even more striking were comparisons of age-, sex-, race-, and zip code-adjusted use among individuals in the last 6 months of life. In each year between 2003 and 2009, not only were hospital admission rates 5%-14% less but ED visits per person in the MA group were fully 42%-54% less than in the comparison group. Common preventive measures such as mammography, hemoglobin A1c testing, and cholesterol testing were carried out at greater frequency in the MA group as well.4

Conclusion: Favorable selection, which plagued MA when first introduced, has been greatly diminished by the introduction of diagnosis-based risk adjustment.

Prior to 1998, MA plans were paid 95% of TM spending in a given county, adjusted for age, sex, Medicaid eligibility, institutionalization, and employment. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that Medicare actually spent 8% more on those enrolled in MA at the time because they were sufficiently better risks than those enrolled in TM. As a result, the 1997 Balanced Budget Act directed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to use diagnoses recorded on claim forms to adjust reimbursement; thus, plans would be reimbursed more for a beneficiary with a serious chronic condition (eg, cancer) than a beneficiary without such a diagnosis. CMS initiated this effort in 2000, but it was not fully implemented until 2007. Although some favorable selection into MA may remain, it now is at low levels and arguably not a large policy concern.5–7 It was often said, only half in jest, that we would know risk adjustment was adequate when MA plans began to advertise for sick persons. Although some were skeptical about this ever happening, we now see plans in the younger than age 65 marketplaces advertising for persons with diabetes to enroll.8

The introduction of diagnosis into the risk-adjustment scheme raised a new concern. MA plans were so aggressive about recording diagnoses that there was concern that CMS was paying more for care of the same person in MA than that person would have cost in TM. To address this issue, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) introduced a coding intensity adjustment; MA reimbursement was reduced annually beginning in 2010, with a 5.4% reduction in risk scores in 2016 and with adjustments through 2016 amounting to a more than 20% reduction in risk scores. Under current law, the reductions are to continue until risk adjustment is based on MA encounter data rather than TM data; MA is currently phasing into encounter data as a diagnosis source, and in 2017 risk adjustment will be 25% based on encounter data. There is still debate about whether the current coding intensity adjustment sufficiently accounts for coding pattern differences in MA and TM.3,9

Although the ACA calls for risk adjustment to be based on MA data, doing so would not lead to an efficient allocation of persons between MA and TM. If MA can deliver the same outcome for persons with certain diagnoses at a lower cost than TM, it is technically efficient for those persons to be in MA and vice versa. Basing payment to MA plans on TM cost for a given mix of diagnoses does this; MA plans will seek out patients who afford them a cost advantage, and not patients for whom TM has a cost advantage.

The comparisons we made were with TM as it historically existed; however, TM has been changing and is likely to evolve further with the advent of accountable care organizations, bundled payments, and reimbursement reforms under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), all of which seek to change financial incentives of providers in the TM program. How MA will compare with a remodeled TM program, and indeed how many provider organizations will seek to become MA plans, will be important to monitor going forward.

References

- 1.McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Sinaiko AD. An economic history of Medicare Part C. Milbank Q. 2011;89:289–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newhouse JP, McGuire TG. How successful is Medicare Advantage? Milbank Q. 2014;92:351–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March, 2016. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/march-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=0 Accessed September12, 2016

- 4.Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders RC, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP. Medicare beneficiaries more likely to receive appropriate ambulatory services in HMOs than in traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1228–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McWilliams JM, Hsu J, Newhouse JP. New risk-adjustment system was associated with reduced favorable selection in Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2630–2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newhouse JP, Price M, Huang J, McWilliams JM, Hsu J. Steps to reduce favorable risk selection in Medicare Advantage largely succeeded, boding well for health insurance exchanges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2618–2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newhouse JP, Price M, McWilliams JM, Hsu J, McGuire TG. How much favorable selection is left in Medicare Advantage? Am J Health Econ. 2015;1(1):1–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews M. New health plans offer discounts for diabetes care. November 17, 2015. http://khn.org/news/new-health-plans-offer-discounts-for-diabetes-care/ Accessed September12, 2016

- 9.Kronick R, Welch WP. Measuring coding intensity in the Medicare Advantage program. MMRR. 2014;4(2):E1-E19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Behavioral Economics: Key to Effective Care Management Programs for Patients, Payers, and Providers

Recent years have highlighted a shift away from the reactive, visit-based model of health care financing and toward a new era of proactive, health outcomes-based models (eg, primary care medical homes, accountable care organizations) wherein provider organizations are at financial risk for quality of care and insurance premiums are increasingly linked to patients' health behaviors and/or outcomes. This has heightened the importance of patient engagement. This is especially true for those in Medicare with chronic conditions who account for a disproportionate share of health care expenditures and may find it difficult to manage their own care. Medicare Advantage's capitated system provides a framework that enables plans to test different care management strategies.

Today, providers as well as public and private insurers, including those that offer Medicare Advantage plans, are engaging in a variety of tactics aimed at promoting positive health behaviors. Although these programs are well-intended, many are built on traditional economic models that do not take into account common decision errors and predictably irrational behavior. These programs often have minimal impact or produce unintended consequences. Programs built on a behavioral economic model leverage evidence about human psychology and decision making into their designs, making them more effective.

Financial incentive programs

Incentive-based wellness programs (eg, a $150 reward – paid at the end of a year – for going to the gym 100 times) have become increasingly popular. However, a national survey estimated that participation rates in many such programs are low (5%-10%), particularly in programs that target smoking or obesity. One reason for low enrollment is failure to take basic principles of behavioral economics into account; the 100-visit threshold is too hard to reach for someone who does not already go to the gym, the feedback at the end of the year is far away in time and not very motivating at the beginning of the year, and the incentive is relatively small ($1.50 per visit).1

A recent study on the effect of financial incentives (to primary care physicians, patients, or both) on lipid levels concluded that shared incentives resulted in a statistically significant difference in the reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels at 12 months, whereas incentives to physicians or patients alone did not.2 This is because many chronic diseases require action by both providers and patients and although the provider incentive increased medication intensification and the patient incentive increased adherence, only the shared incentive arm resulted in both intensification of therapy by providers and higher patient adherence. Forty-nine percent of patients in the shared patient-physician incentive group achieved the LDL-C goal compared to 36%-40% of patients in comparison groups.

Automated hovering3

For more than 2 decades, disease management programs have attempted to engage patients in managing their chronic conditions (eg, diabetes) and, more recently, transitional care models have been touted as an effective means for coordinating care post hospitalization. These conventional “hovering” approaches are personnel based (eg, visiting nurses, telemedicine services) and expensive, and results have been mixed. For instance, a large multicenter trial of telemonitoring for patients with heart disease showed no effect on the primary outcomes of rehospitalization and death. Moreover, 14% of those assigned to the intervention group did not use the system at all and nearly half of those who did lost interest over time.

As medication adherence has taken on greater importance, home-based biometric assessments of various indicators have emerged as a longitudinal part of clinical care. The challenge lies in automating the hovering – thereby reducing its cost – and incorporating this monitoring into patients' lives in ways that are acceptable, convenient, and even welcomed. Three recent developments suggest that automated hovering may offer promise:

1. The payment mechanisms that support accountability for health outcomes (eg, non-reimbursement for preventable admissions, bundled payments around goals of care) also provide the financial engine to support automated hovering initiatives.

2. Although most people want better health and typically know what is required to achieve it, distractions and urgencies of the moment often get in the way of pursuing long-term wellness goals. Behavioral economics explains why individuals behave this way and provides tools for redirecting behavior toward health goals with carefully deployed nudges and financial incentives.

3. The expanded reach of today's simple and more sophisticated technologies (eg, cell phones, wireless devices) that can help experts connect to people during their everyday lives were not part of traditional disease management programs in the past.

This type of automated hovering must be targeted to the right clinical and social circumstances (eg, patients with conditions whose management depends substantially on their own behavior – those with heart failure or acute coronary artery syndromes that must strictly adhere to medication). In one study, patients taking warfarin via a home-based pill dispenser that was electronically tethered to a lottery system were automatically entered in a daily random drawing with a small chance of winning $100 and a larger chance of winning $10. Each day, patients were electronically notified if their number had come up – but they were eligible for the prize only if they'd taken their warfarin the previous day as signaled by the dispenser. The system provided daily engagement, the chance of a prize, and a sense of anticipated regret. Although the expected value was less than $3 a day, the system reduced the rate of incorrect doses from 22% to ∼3% and reduced the rate of out-of-range international normalized ratios from 35% to 12%.

Much is yet to be understood regarding the types of patients, approaches, conditions, and settings in which these programs would be most helpful in Medicare. Clinical and research opportunities in behavioral economics should be pursued in conjunction with careful, iterative testing because these new forms of patient engagement will be central to improving population health in the future. Understanding how different payment frameworks enable or inhibit care management strategies is another important element that must be investigated.

References

- 1.Loewenstein G, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Behavioral economics holds potential to deliver better results for patients, insurers, and employers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1244–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asch DA, Troxel AB, Stewart WF, et al. . Effect of financial incentives to physicians, patients or both on lipid levels. JAMA. 2015;314:1926–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asch DA, Muller RW, Volpp KG. Automated hovering in health care – watching over the 5000 hours. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:1–3.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Value-Based Insurance Design: A Promising Strategy for Medicare Advantage

A. Mark Fendrick, Susan Lynne Oesterle, Pat Oungpasuk, Ruchi Aggarwal

As health care expenditures have risen, payers have sought to alleviate the upward pressure on premiums by increasing patients' cost sharing at the point of service. In traditional Medicare benefit designs, the out-of-pocket costs do not reflect the expected clinical benefit or the value of care. Research indicates that increasing patient cost sharing reduces utilization of all care, not only that which is nonessential.1 Thus, patients would benefit if traditional blunt cost-sharing structures were replaced with more sophisticated benefit designs.

Policy makers have begun to explore consumer-facing strategies and complementary provider-facing payment reforms as a means to contain Medicare spending increases without compromising quality of care.2 One such strategy, value-based insurance design (V-BID), focuses on encouraging efficient use of services by aligning patients' out-of-pocket costs (eg, co-payments, deductibles) with the value of services delivered. V-BID plans follow the tenets of “clinical nuance”; namely, that medical services differ in the amount of health produced, and that the clinical benefit derived from a specific service depends on the consumer using it as well as when and where the service is provided.3 Initially driven by private payers, clinically nuanced cost sharing was included in Section 2713 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act as a means of eliminating patient cost sharing for primary preventive services for specified populations as determined by the US Preventive Services Task Force, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other agencies.4

Incorporation of V-BID principles into Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage (MA) has garnered multistakeholder and bipartisan political support. The Seniors' Medication Copayment Reduction Act of 2009 sought to remove consumer cost barriers associated with high-value medications for conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and depression.5 V-BID was highlighted in the 2010–2012 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Reports to Congress. Subsequently, the bipartisan, bicameral Better Care, Lower Cost Act of 2014 called for an elective program that reduced cost sharing for high-value services for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions.6

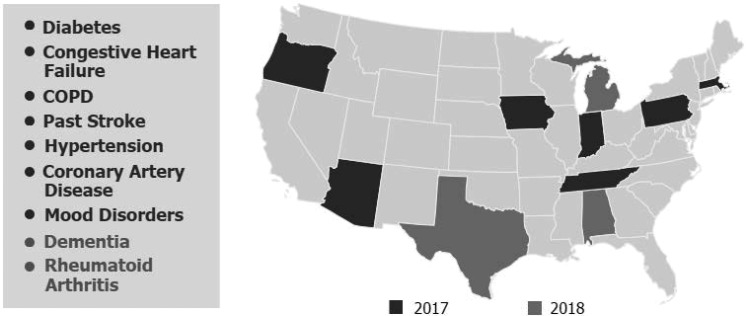

Most notably, the Strengthening Medicare Advantage through Innovation and Transparency for Seniors Act of 2015 that was passed with strong bipartisan support directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a demonstration program allowing MA plans to test V-BID principles. Shortly thereafter, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced an MA V-BID model test to assess the utility of structuring consumer cost sharing and health plan elements to encourage the use of high-value clinical services and providers.7 This demonstration was expanded in 2016 to include 3 additional states and 2 additional chronic conditions9 (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Medicare Advantage value-based insurance design model test. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

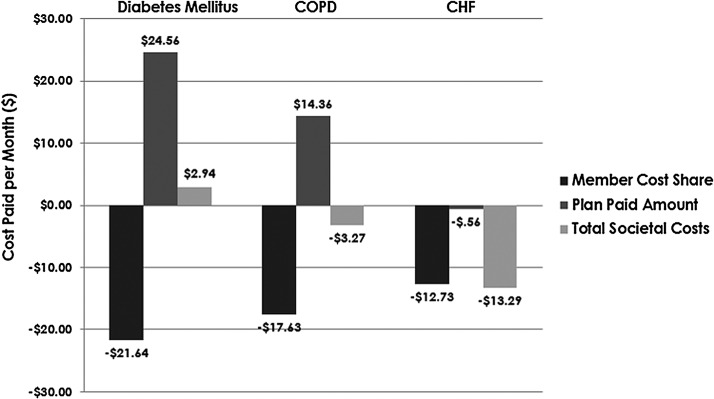

An actuarial analysis of the fiscal implications of condition-specific MA V-BID programs from the patient, plan, and societal perspectives was undertaken for diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and congestive heart failure (CHF) (Figure 2). The V-BID programs reduced consumer out-of-pocket costs in all 3 conditions. Plan costs increased slightly for DM and COPD and the plan realized cost savings for CHF. From the societal perspective, the DM program was close to cost neutral; net societal savings resulted in the COPD and CHF programs.10

FIG. 2.

Actuarial analysis of Medicare Advantage value-based insurance design programs, by condition and stakeholder. CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

V-BID principles can be used to create MA plan designs that are better aligned with value. Encouraging the use of high-value services and providers, and discouraging those with low value, will decrease cost-related nonadherence, reduce health care disparities, and improve the efficiency of health care spending without compromising quality. The evidence suggests that the use of clinical nuance to set out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries would have significant positive impacts, providing consumers with better access to quality services and resulting in a healthier population.10

References

- 1.Chernew ME, Fendrick AM, Spangler K. Implementing value-based insurance design in the Medicare Advantage program. 2013. http://vbidcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ImplementingVBIDintheMedicareAdvantageProgram_May2013.pdf Accessed October12, 2016

- 2.Chernew ME, Fendrick AM. Improving benefit design to promote effective, efficient, and affordable care. JAMA. Published ahead of print September 26, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. Understanding clinical nuance. http://vbidcenter.org/initiatives/v-bid-clinical-nuance/ Accessed September9, 2016

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Preventive health services. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/preventive-care-benefits/ Accessed October12, 2016

- 5.Iseler J. U-M center plays key role in Medicare proposal. 2009. http://www.ur.umich.edu/0809/May18_09/46.php Accessed October12, 2016

- 6.Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. V-BID concepts included in new Medicare legislation to improve care and lower costs. 2014. http://vbidcenter.org/v-bid-concepts-included-in-new-medicare-legislation-to-improve-care-and-lower-costs/ Accessed September9, 2016

- 7.Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. V-BID Medicare Advantage bill passes House of Representatives. 2015. http://vbidcenter.org/news-update-v-bid-medicare-advantage-bill-passes-house-of-representatives/13258/ Accessed September9, 2016

- 8.Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. CMMI announces Medicare Advantage V-BID model test. 2015. http://vbidcenter.org/cmmi-announces-medicare-advantage-v-bid-model-test/ Accessed September9, 2016

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Advantage Value-Based Insurance Design model test – advanced notice of CY 2018 model changes. 2016. https://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/vbid-hpmsmemo.pdf Accessed October12, 2016

- 10.Fendrick AM, Oesterle SL, Lee HM, et al. . Incorporating value-based insurance design to improve chronic disease management in the Medicare Advantage program. 2016. http://vbidcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/MA-White-Paper_final-8-16-16.pdf Accessed October12, 2016

Two Perspectives on the Future of Medicare Advantage

Private insurance plans containing at least the same benefits as Traditional Medicare (TM) were first introduced almost 40 years ago. The program currently known as Medicare Advantage (MA) has evolved since then, with successive changes in how these private plans are structured and paid for by Medicare. Currently, 32% of Medicare beneficiaries choose to participate in MA, and payment for their care is based on a bidding model. The continued growth in MA – despite lower Medicare payments to plans that were legislated by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – has been a pleasant surprise.

Although Medicare remains very popular among seniors, it faces some serious fiscal challenges. Like the rest of health care, Medicare has experienced a recent slowdown in the rate of overall spending increases and a modest decline on a per capita basis. The fact that costs haven't risen is likely related to the 2008 global recession; in fact, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found even greater reductions in cost growth on average for all OECD countries from 2009 through 2014 compared to the US slowdown. The concern is that, as the recession recedes, costs may once again grow at unsustainable rates.

Medicare also will face substantial fiscal pressures because of the large population of baby boomers, who began to reach age 65 in 2011 and will continue to swell the program's rolls until the last of them reaches age 65 in 2030 – a potential increase of some 27 million individuals. Medicare is currently experiencing favorable effects from the growing numbers of younger, lower-risk seniors who are joining the program and also because of the lower Medicare payments to plans legislated by the ACA. The ACA also has encouraged a variety of service delivery reforms (eg, accountable care organizations, patient-centered medical homes) although their effects on spending are not yet clear.

Because the baby boomers who are retiring today are more accustomed to network health plans than their Medicare predecessors, MA is likely to remain an attractive option. It has particular appeal for beneficiaries in the lower-middle-income group (above the cutoff for Medicaid) who find it more affordable than “Medigap” plans as a means for supplementing their benefits from TM. Because of this, as well as the growing number of retirees familiar with network plans, the growth in MA is likely to continue in the future.

To help make Medicare more fiscally sustainable, I favor a premium support model, with competitive bidding, and the retention of TM as one of the plan choices. A subsidy – based on a Medicare Premium Support Model – could achieve cost savings while allowing people to choose the plan that works best for them. This alone, however, is unlikely to solve all of Medicare's fiscal challenges.

In addition to encouraging greater efficiencies, MA is a way to circumvent the current “stovepipes” in Medicare Parts A, B, and D that make it difficult – or impossible – to coordinate care for seniors on Medicare. TM views the component parts of Medicare (Parts A, B, and D) as independent and unrelated in terms of their effects on care management and also on the costs of care, even though it is well recognized that improved use of physician services or the appropriate use of prescriptions drugs can lower the costs of other parts of health care. MA is also attractive because it allows the physician, hospital, pharmacist, home care, and other providers to take better care of patients with complex needs. Even though patients may not always take full advantage of available services, care coordination is easier to accomplish within an MA plan than it is in TM. In fact, care coordination is symbolic of the problem with TM; benefits are parceled into separate pieces and clinicians are unrelated to one other, making it harder to coordinate care for those seniors who see a variety of clinicians or use many Medicare services.

Private plans cannot provide better care than TM if barriers that prevent coordination remain and best practices and medical findings are not shared. MA has the potential to make it easier for clinicians to coordinate services whereas TM makes it more difficult. As better outcomes information becomes available, seniors and their families should find it easier to choose the plans that best meet their medical needs. And, with properly structured subsidies for private plans and TM that are set by competitive bidding, MA plans could help make Medicare more fiscally sustainable.

Kathleen Sebelius is a former Secretary of HHS (2009–2014) and served previously as Governor of Kansas. She is CEO of Sebelius Resources, LLC

From day 1 as Secretary of HHS, I was engaged in the passage and implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), the Obama administration's expansive plan to reform the US health care system. The 3 main goals were challenging but, ultimately, achievable:

1. Provide affordable health insurance for individuals who either have no access to employer-sponsored health plans or are unable to find a plan that is within their financial reach.

2. Assure better quality patient care and a healthier population by means of adequate preventive services and early intervention – the right care to the right patient at the right time.

3. Implement a strategy to lower and contain US health care costs so that outcomes are commensurate with expenditures.

Medicare Advantage (MA) is an important component of choice for Medicare-eligible Americans; approximately one third of Medicare beneficiaries are now choosing MA. The intrinsic value of MA is that people enrolled in the program receive coordinated care, thus improving their chances of staying healthy or recovering from their illnesses.

Huge change was brought about in 2009 with the move toward electronic medical records and transparent data. The government can now create value propositions and measure whether they are working. With these as underpinnings and transparent quality metrics, MA is well positioned to be viable in the future.

Although some opponents of the ACA argued that measures to ensure quality and lower costs would destroy the program, they were wrong. Now, 6 years later, more plans participate, costs are lower, and more beneficiaries each year choose to enroll in an MA plan.

The promise of MA is to deliver better, more cost-effective care for a given population. Some plans will do this better than others as the playing field levels and costs for MA and Fee-for-Service Medicare are brought into alignment.

As we move forward, it will continue to be important to track progress toward delivering on the promises of the ACA. It is unclear what changes a new Republican administration might bring, as the campaign of that party's presidential nominee was virtually silent on health care policy. Secretary Clinton's proposal is conceptually aligned with current reforms; she was quoted as saying that we need to “defend the ACA and fix it” rather than start again from square one. Strengthening Medicare is a critical component of her proposal, along with the assurance that MA will continue to be robust with its triple goal of continuously improving the quality of care, reducing the cost of care, and delivering coordinated care.

The number of early retirees ranks just behind young adults in the uninsured adult category. We need a comprehensive care strategy whereby early indicators of chronic illness can be identified and managed early. MA ensures that care will be more patient-centered and coordinated. In a system where progression can be delayed and care can be managed effectively in coordinated fashion, there is no need to contract for every service separately as is the case with Fee-For-Service Medicare.

Initiatives such as quality assessments and medical loss ratios will continue to ensure the promises of the 1980s (ie, not only lower costs but also improved health status). The trend toward paying for high-quality outcomes will continue as part of the value proposition; we'll be looking at what happens to the Medicare population in terms of fewer seniors with diabetes and more seniors living healthier lives in their home settings.