Abstract

A 32‐year‐old man presented with palpitation. He was diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis by lung biopsy. The electrocardiogram showed first‐degree atrioventricular block and complete right bundle branch block (CRBBB). We planned to examine laboratory data, echocardiography, Holter monitoring, and gallium‐67 scintigraphy. Before he went through all these exams, he developed ventricular tachycardia. After defibrillation was performed, his electrocardiogram revealed complete atrioventricular block. We observed elevation of serum angiotensin‐converting enzyme levels. In addition, both of gallium‐67 scintigraphy and 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed abnormal uptake in the ventricular septum. We diagnosed the patient with cardiac sarcoidosis associated with these arrhythmias. We started treatment with methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1 g daily). After 3 days of steroid pulse therapy, we administered prednisolone 30 mg daily. On day 15, electrocardiogram changed from complete atrioventricular block to first‐degree atrioventricular block and CRBBB. He was discharged with no progression with cardiac sarcoidosis for 2 years.

Keywords: Cardiac sarcoidosis, Arrhythmia, Steroid pulse therapy

Introduction

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a rare but life threatening risk factor of sarcoidosis. It may present with various manifestations including ventricular tachycardia (VT), atrioventricular (AV) block, and congestive heart failure. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown aetiology. Noncaseating granulomas are the pathological hallmark of sarcoidosis and are most often associated with pulmonary and lymph node involvement but they may also involve the heart, liver, spleen, skin, eyes, or other organs and tissues.1 Steroid therapy is the first line agent for cardiac sarcoidosis. It is presumed that the substrate for arrhythmias includes inflammation and following fibrosis because of sarcoidosis as well as acute fulminant myocarditis. Complete AV block because of cardiac sarcoidosis recovered to normal sinus rhythm after corticosteroid therapy in 57%.2, 3 On the other hand, a systemic review demonstrated that corticosteroids might have little benefit on VT from cardiac sarcoidosis.4

We experienced a case of cardiac sarcoidosis associated with VT and complete AV block successfully treated with steroid pulse therapy. In the early phase of inflammation, immunosuppressive therapy including steroid might be effective for cardiac sarcoidosis with arrhythmia and left ventricular dysfunction.

Case report

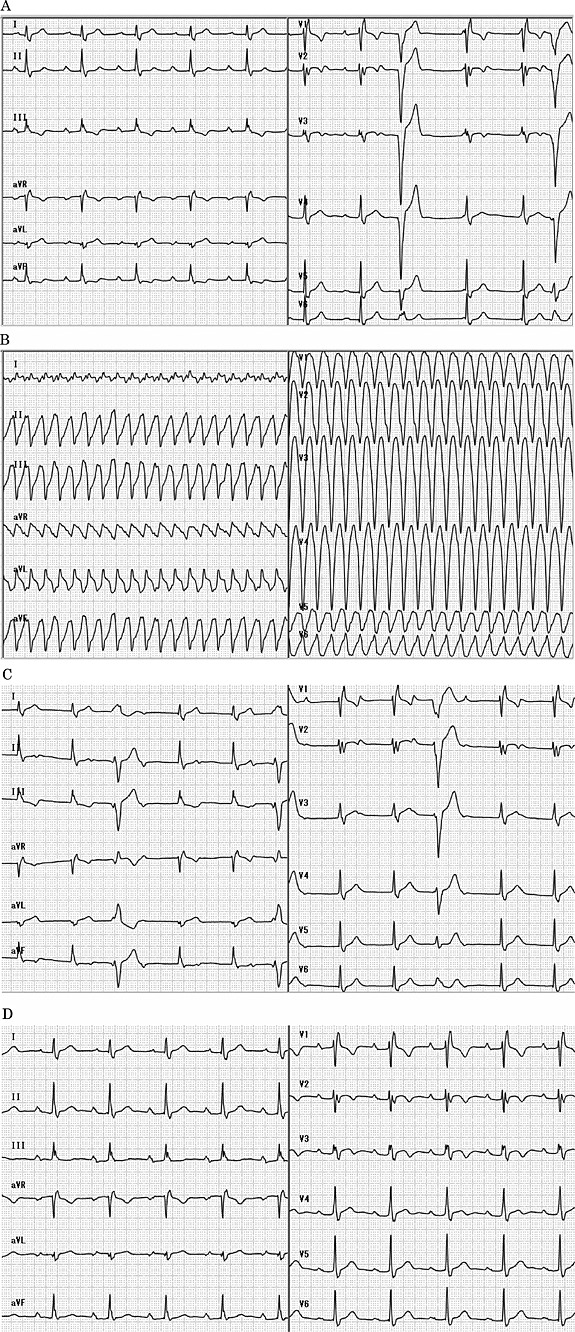

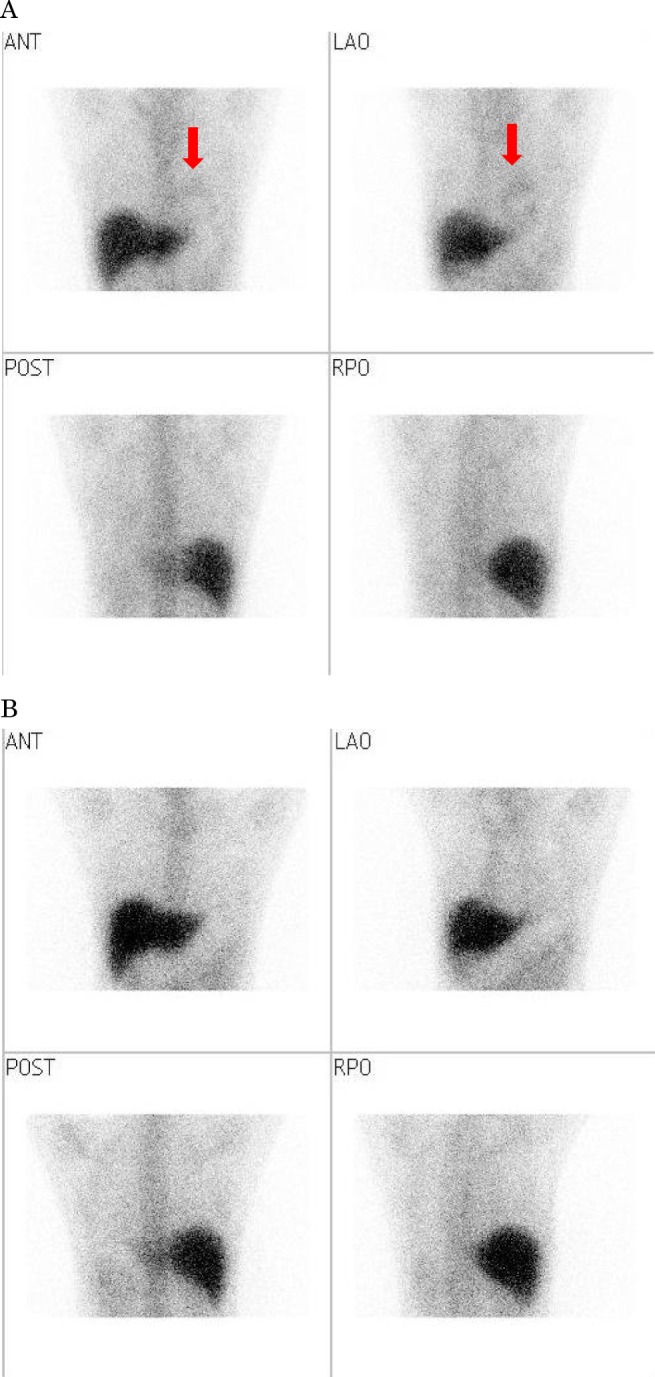

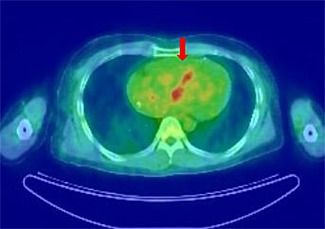

A 32‐year‐old man visited our hospital complaining of palpitation. Initial onset of the symptom occurred 5 days ago. The electrocardiogram showed first‐degree AV block and complete right bundle branch block (CRBBB) (Figure 1 A). He was diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis by lung biopsy a few years ago. We suspected cardiac sarcoidosis and evaluated laboratory data, echocardiography, Holter monitoring, and gallium‐67 scintigraphy. One week later, he developed palpitation and was taken to our hospital by ambulance. The electrocardiogram showed VT (heart rate 231/min) (Figure 1 B). His blood pressure was 111/72 mmHg and consciousness was clear. Chest X‐ray did not show any congestion. After defibrillation was successful with 200 J, his electrocardiogram showed complete AV block (Figure 1 C). Amiodarone infusion was started to prevent VT. Temporary pacemaker was placed and coronary angiography was performed with negative results. Left ventriculography showed diffuse hypokinesis. The echocardiography also showed a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (24%) with septal thinning. Other imaging modalities were performed to further evaluate his heart. Gallium‐67 scintigraphy demonstrated an abnormal uptake in the heart (Figure 2 A). The 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG‐PET) also demonstrated abnormal accumulation at ventricular septum (Figure 3). With regard to laboratory data, serum angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) level and serum calcium level were elevated (25.2 U/L and 10.2 mg/dL, respectively). We therefore diagnosed cardiac sarcoidosis associated with VT and complete AV block based on guidelines established in 2006 by the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare.5

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram. A is the initial electrocardiogram. It showed first‐degree atrioventricular block, complete right bundle branch block, and premature ventricular contractions. B is the electrocardiogram when he developed ventricular tachycardia. C is the electrocardiogram after defibrillation was successful with 200 J. It showed complete atrioventricular block. D is the electrocardiogram after being on steroid therapy for 2 weeks. It changed from previous complete atrioventricular block to first‐degree atrioventricular block and complete right bundle branch block.

Figure 2.

Gallium‐67 scintigraphy. A is the image of gallium‐67 scintigraphy that demonstrated an abnormal uptake in the heart before steroid therapy. B is the image of gallium‐67 scintigraphy that showed no uptake in the heart after steroid therapy.

Figure 3.

18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. The image of 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed abnormal accumulation at ventricular septum before steroid therapy.

Methylprednisolone was administered intravenously at a dose of 1 g per day for 3 days as a steroid pulse therapy. From day 4, prednisolone was orally administered 30 mg per day. Amiodarone was continued by oral administration. On day 7, echocardiography showed improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction to 53% and septal thinning remarkably improved. Serum ACE level decreased to 12.9 U/L. After being on steroid therapy for 2 weeks, electrocardiogram changed from previous complete AV block to first‐degree AV block and CRBBB (Figure 1 D). On day 21, gallium‐67 scintigraphy was performed to assess the sarcoidosis activity after steroid therapy and showed no uptake in the heart (Figure 2 B). His temporary pacemaker was removed and he was discharged from the hospital after a total stay of 27 days. He has been followed for 2 years with no recurrence of VT, complete AV block, or left ventricular dysfunction.

Discussion

Several case reports demonstrated the efficacy of steroid in the treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis. Small‐sized retrospective studies showed that steroid improved nearly 50% of cardiac sarcoidosis patients with complete AV block.2, 3 Chapelon‐Abric et al. demonstrated that clinical response to prednisolone was limited to the early stage of cardiac sarcoidosis.6 In addition, other studies suggested that steroid was less effective in cardiac sarcoidosis patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction.7

Gallium‐67 scintigraphy showed abnormal uptake in the heart, which is associated with the inflammatory activity of sarcoidosis.8 We also performed FDG‐PET to assess inflammatory activity, which is more sensitive than gallium‐67 scintigraphy.9

In our case, inflammation from cardiac sarcoidosis was initially apparent according to the findings of both gallium‐67 scintigraphy and FDG‐PET. After steroid pulse therapy and following oral steroid administration, abnormal findings disappeared in gallium‐67 scintigraphy. It is considered that steroid pulse therapy was markedly effective because our case was in the early active phase of inflammation from sarcoidosis.

In patients with some autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus and IgA nephropathy, steroid pulse therapy was more effective than conventional steroid oral administration. In the early phase of inflammation, steroid pulse therapy immediately suppressed the inflammation in glomerulus.10 Regarding steroid pulse therapy for cardiac sarcoidosis, this is the first case report in which steroid pulse therapy was effective in patient with cardiac sarcoidosis in active inflammation phase. Because cardiac sarcoidosis is a rare disease, large‐scale randomized controlled trial is difficult to perform.

We experienced a very rare case of cardiac sarcoidosis in which steroid pulse therapy was remarkably effective for complete AV block and VT. This case suggested that in the early phase of inflammation, immunosuppressive therapy including the steroid pulse therapy might be a feasible treatment option for cardiac sarcoidosis with arrhythmia and left ventricular dysfunction.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Okabe, T. , Yakushiji, T. , Hiroe, M. , Oyama, Y. , Igawa, W. , Ono, M. , Kido, T. , Ebara, S. , Yamashita, K. , Yamamoto, M. H. , Saito, S. , Hoshimoto, K. , Kisaki, A. , Isomura, N. , Araki, H. , and Ochiai, M. (2016) Steroid pulse therapy was effective for cardiac sarcoidosis with ventricular tachycardia and systolic dysfunction. ESC Heart Failure, 3: 288–292. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12095.

References

- 1. Roberts WC, McAllister HA, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart: a clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients. Am J Med 1977; 63: 86–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banba K, Kusano KF, Nakamura K, Morita H, Ogawa A, Ohtsuka F, Ogo KO, Nishii N, Watanabe A, Nagase S, Sakuragi S, Ohe T. Relationship between arrhythmogenesis and disease activity in cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm 2007; 4: 1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kato Y, Morimoto S, Uemura A, Hiramitsu S, Ito T, Hishida H. Efficacy of corticosteroids in sarcoidosis presenting with atrioventricular block. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2003; 20: 133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sadek MM, Yung D, Birnie DH, Beanlands RS, Nery PB. Corticosteroid therapy for cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review. Can J Cardiol 2013; 29: 1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diagnostic standard and guidelines for sarcoidosis. Jpn J Sarcoidosis and Granulomatous Disorders [in Japanese] 2007; 27: 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chapelon‐Abric C, de Zuttere D, Duhaut P, Veyssier P, Wechsler B, Huong DL, de Gennes C, Papo T, Blétry O, Godeau P, Piette JC. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83: 315–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yodogawa K, Seino Y, Ohara T, Takayama H, Katoh T, Mizuno K. Effect of corticosteroid therapy on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2011; 16: 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Connell JB, Henkin RE, Robinson JA, Subramanian R, Path MRC, Scanlon PJ, Gunnar RM. Gallium‐67 imaging in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and biopsy‐proven myocarditis. Circulation 1984; 70: 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okumura W, Iwasaki T, Toyama T, Iso T, Arai M, Oriuchi N, Endo K, Yokoyama T, Suzuki T, Kurabayashi M. Usefulness of fasting 18F‐FDG PET in identification of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med 2004; 45: 1989–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katafuchi R, Ninomiya T, Mizumasa T, Ikeda K, Kumagai H, Nagata M, Hirakata H. The improvement of renal survival with steroid pulse therapy in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23: 3915–3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]