Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the relationship between the background of preoperative cataract patients and bacterial conjunctival flora.

Methods

A total of 990 cataract patients who had completed preoperative examinations in 2007 and 2008 were included. Patients using topical antibiotics at the preoperative examination or having a history of intraocular surgery were excluded. Conjunctival cultures had been preoperatively obtained. Patient characteristics were investigated via medical records. Risk factors for conjunctival flora of seven typical bacteria were analyzed by univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

The detection rate of alpha-hemolytic streptococci and Enterococcus faecalis increased with age (P=0.044 and P=0.002, respectively). The detection rate of Gram-negative bacilli was higher among patients with oral steroid use or lacrimal duct obstruction (P=0.038 and P=0.002, respectively). The detection rate of Corynebacterium species was higher among older patients and men, and lower among patients with glaucoma eye drop use (P<0.001, P=0.012 and P=0.001, respectively). The detection rate of methicillin-susceptible coagulase-negative Staphylococci was higher among men and lower among patients with a surgical history in other departments (P=0.003 and P=0.046, respectively). The detection rate of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci (MR-CNS) was higher among patients with oral steroid use, a visit history to ophthalmic facilities, or a surgical history in other departments (P=0.002, P=0.037 and P<0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

Elderly patients, men, patients with lacrimal duct obstruction or immunosuppressed patients are more likely to be colonized by pathogens that cause postoperative endophthalmitis. Moreover, MR-CNS colonization was associated with healthcare-associated infection.

Introduction

Bacterial conjunctival flora may be the causative organism in postoperative endophthalmitis.1 Endophthalmitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and gram-negative bacilli such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa is likely to be severe.2 Moreover, multidrug resistance of conjunctival bacterial flora has become a serious problem.3 Recently, it was reported that multidrug-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci (MR-CNS) are detected from conjunctiva.4

To combat the threat of postoperative endophthalmitis, it is necessary to clarify the epidemiological characteristics of bacterial conjunctival flora. Studies on risk factors for conjunctival bacterial colonization have reported higher detection rates of conjunctival bacteria in elderly or male patients.5, 6, 7, 8 In addition, there was a positive correlation between the dose of prednisolone and the number of bacterial isolates.9 There are also reports that atopic dermatitis and diabetes affected the bacterial conjunctival flora.8, 10, 11, 12 Our study design was constructed in consideration of the following two points. First, we focused on the detection rate of each bacteria separately rather than that of total bacterial isolates because of variations in the pathogenicity, auxotrophy and transmission route in each type of bacteria. Next, we focused on the possibility of healthcare-associated infection. Multidrug-resistant bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococci often become a problem as causative organisms of healthcare-associated infection. Therefore, the visit history to ophthalmic facilities and the surgical history in other departments were adopted in our study as an indicator of healthcare-associated infection.

In the present study, we investigated the patient background associated with each type of conjunctival bacteria by using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses and revealed that preoperative cataract patients had specific risk factors for each type of conjunctival bacteria.

Materials and methods

Investigation of patient background

Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Machida Hospital. All cataract patients from July 2007 to August 2008 who satisfied the selection criteria and gave informed consent were included in this study. Patients using topical antibiotics at the preoperative examination or having a history of intraocular surgery were excluded. The numbers of included patients and potential patients were the same. All patients who fit the inclusion criteria had completed all of the preoperative examinations. Conjunctival swab collection, lacrimal irrigation test, blood pressure measurement and blood tests were performed before cataract surgery. The following patient characteristics were collected from medical records: age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, oral steroid use, lacrimal duct obstruction, glaucoma eye drop use, visit history to ophthalmic facilities within 6 months and surgical history in other departments within 3 years. The 6-month and 3-year periods were set for convenience as ranges that could be collected from medical records as accurately as possible. If the subject was previously treated in the internal medicine department or started treatment after the preoperative examination, we determined the presence of hypertension or diabetes. After collecting the conjunctival swab, the presence of lacrimal duct obstruction was determined.

Bacterial identification from conjunctival swabs

Conjunctival swabs were collected from one eye for which surgery had been scheduled for the first time. The lower fornix of the conjunctiva was swabbed with a cotton swab that was first soaked in sterile saline. The swab was placed into transport medium (BBL CultureSwab Plus, Nippon Becton Dickinson, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and sent to the microbiological laboratory. Specimens were incubated under aerobic and enrichment conditions at 35 °C for 3 days by using sheep blood agar, chocolate agar, BTB agar and thioglycollate broth. Methicillin resistance of the Staphylococcus species was determined according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (M100-S17, 2007, and M100-S18, 2008).

Analysis of risk factors for bacterial conjunctival flora

First, univariate analysis was performed to determine whether conjunctival carriage of each of the seven types of bacteria (methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), alpha-streptococci, Enterococcus faecalis, gram-negative bacilli, Corynebacterium species, methicillin-susceptible coagulase-negative Staphylococci (MS-CNS) and MR-CNS were associated with nine background factors (age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, oral steroid use, lacrimal duct obstruction, glaucoma eye drop use, visit history to ophthalmic facilities and surgical history in other departments). The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for analysis of age, and Fisher's exact test was used for the analysis of other background factors. P-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Next, each of the seven types of bacteria were set as objective variables, nine background factors were set as explanatory variables, and multivariate analysis was performed. The female sex was set as 0, and the male sex was set as 1 to transform variables. Correlation of seven objective variables and nine explanatory variables was examined by using Spearman's correlation coefficient prior to multivariate analysis. It was confirmed that the correlation coefficient of all variables was <0.3, and the correlation was not as strong with each other. Logistic regression analysis was performed by using the forced entry method. It was confirmed that the significance probability was <0.05 by the omnibus test of model coefficients for all adopted models. All statistical analyses were performed by using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 for Windows (IBM Japan, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Patient background

A total of 990 cataract patients were included in this study. The male:female ratio was 1 : 1.5. The average age was 73.9±10.1 years (range, 15 to 97 years), and 83.3% of patients were over 65 years of age. Among the eligible patients, 533 had hypertension (53.8%), 206 had diabetes (20.8%), 29 used oral steroids (2.9%), 31 had lacrimal duct obstruction (3.1%), 97 used glaucoma eye drops (9.8%), 725 visited ophthalmic facilities within the past 6 months (73.2%) and 74 had surgery in other departments within the past 3 years (7.5%).

Composition of bacterial isolates

Positive culture results were obtained from 719 of 990 cases. Table 1 shows the details of bacterial isolates from the conjunctival sac. Two strains of Streptococcus pneumonia are included in the group of other gram-positive cocci. Four strains of Haemophilus species are included in the group of gram-negative bacilli. Both bacteria of CNS and Corynebacterium species accounted for 80.3% of the total bacterial isolates. Furthermore, the addition of MSSA, alpha-hemolytic streptococci, Enterococcus faecalis and gram-negative bacilli accounted for 96.4% of total isolates. Thus, these seven bacteria were considered the main isolates from conjunctiva of preoperative cataract patients.

Table 1. Composition of the bacterial species isolated from conjunctival sac.

| Bacteria | Number of strains | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Corynebacterium species | 462 | 44.8 |

| Methicillin-susceptible coagulase-negative Staphylococci | 230 | 22.3 |

| Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci | 136 | 13.2 |

| Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus | 44 | 4.3 |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 6 | 0.6 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 36 | 3.5 |

| Alpha-hemolytic streptococci | 31 | 3.0 |

| Other gram-positive cocci | 28 | 2.7 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 55 | 5.3 |

| Gram-negative cocci | 4 | 0.4 |

| Total | 1032 | 100 |

Risk factors for each bacterial conjunctival flora

For MSSA, none of the background factors showed statistical significance in the univariate analysis (Table 2a), and there were no obvious risk factors for carriage of MSSA in the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3a).

Table 2. Univariate analysis for each bacteria.

| Factor |

a. MSSA |

b. Alpha-hemolytic streptococci |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | P-value | Positive | Negative | P-value | |

| N=44 | N=946 | N=31 | N=959 | |||

| Age | 74.9±10.4 | 73.8±10.1 | 0.431 | 77.5±9.0 | 73.7±10.1 | 0.008** |

| Sex (male) | 19/25 | 377/569 | 0.753 | 14/17 | 382/577 | 0.579 |

| Hypertension | 24/20 | 509/437 | 1.000 | 21/10 | 512/447 | 0.143 |

| Diabetes | 6/38 | 200/756 | 0.261 | 10/21 | 196/763 | 0.117 |

| Oral steroids | 2/42 | 27/919 | 0.373 | 2/29 | 27/932 | 0.229 |

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 2/42 | 29/917 | 0.644 | 2/29 | 29/930 | 0.253 |

| Glaucoma eye drops | 6/38 | 91/855 | 0.431 | 5/26 | 92/867 | 0.218 |

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 33/11 | 692/254 | 0.863 | 22/9 | 703/256 | 0.837 |

| Surgical history in other departments | 3/41 | 71/875 | 1.000 | 1/30 | 73/886 | 0.723 |

|

c. Enterococcus faecalis |

d. Gram-negative bacilli |

|||||

| Positive | Negative | P-value | Positive | Negative | P-value | |

| N=36 | N=954 | N=52 | N=938 | |||

| Age | 79.0±7.7 | 73.7±10.1 | 0.001** | 76.6±7.7 | 73.7±10.2 | 0.083 |

| Sex (male) | 12/24 | 384/570 | 0.489 | 21/31 | 375/563 | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 21/15 | 512/442 | 0.614 | 33/19 | 500/438 | 0.198 |

| Diabetes | 9/27 | 197/757 | 0.531 | 13/39 | 193/745 | 0.482 |

| Oral steroids | 1/35 | 28/926 | 1.000 | 4/48 | 25/913 | 0.061 |

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 2/34 | 29/925 | 0.312 | 6/46 | 25/913 | 0.004** |

| Glaucoma eye drops | 3/33 | 94/860 | 1.000 | 4/48 | 93/845 | 0.811 |

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 26/10 | 699/255 | 0.850 | 39/13 | 686/252 | 0.873 |

| Surgical history in other departments | 4/32 | 70/884 | 0.337 | 6/46 | 68/870 | 0.271 |

|

e. Corynebacterium species |

f. MS-CNS |

|||||

| Positive | Negative | P-value | Positive | Negative | P-value | |

| N=460 | N=530 | N=223 | N=767 | |||

| Age | 75.9±8.5 | 72.1±10.9 | 0.000** | 73.0±10.2 | 74.1±10.0 | 0.095 |

| Sex (male) | 200/260 | 196/334 | 0.044* | 110/113 | 286/481 | 0.001** |

| Hypertension | 267/193 | 266/264 | 0.015* | 122/101 | 411/356 | 0.819 |

| Diabetes | 92/368 | 114/416 | 0.583 | 53/170 | 153/614 | 0.224 |

| Oral steroids | 15/445 | 14/516 | 0.577 | 5/218 | 24/743 | 0.653 |

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 17/443 | 14/516 | 0.365 | 6/217 | 25/742 | 0.828 |

| Glaucoma eye drops | 31/429 | 66/464 | 0.003** | 15/208 | 82/685 | 0.096 |

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 337/123 | 388/142 | 1.000 | 159/64 | 566/201 | 0.492 |

| Surgical history in other departments | 39/421 | 35/495 | 0.277 | 10/213 | 64/703 | 0.060 |

|

g. MR-CNS |

||||||

| Positive | Negative | P-value | ||||

| N=135 | N=855 | |||||

| Age | 75.3±10.2 | 74.4±9.9 | 0.228 | |||

| Sex (male) | 52/83 | 344/511 | 0.777 | |||

| Hypertension | 75/60 | 458/397 | 0.711 | |||

| Diabetes | 29/106 | 177/678 | 0.820 | |||

| Oral steroids | 10/125 | 19/836 | 0.003** | |||

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 7/128 | 24/831 | 0.177 | |||

| Glaucoma eye drops | 16/119 | 81/774 | 0.435 | |||

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 109/26 | 616/239 | 0.036* | |||

| Surgical history in other departments | 20/115 | 54/801 | 0.001** | |||

Abbreviation: N, number of patients.

The data indicate real or mean±SD.

Mann–Whitney U-test was used for age, Fisher's exact test was used for others.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis for each bacteria.

| Factor |

a. MSSA |

b. Alpha-hemolytic streptococci |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 1.007 | 0.975–1.041 | 0.671 | 1.049 | 1.001–1.100 | 0.044* |

| Sex (male) | 0.803 | 0.432–1.494 | 0.489 | 1.287 | 0.613–2.704 | 0.505 |

| Hypertension | 0.971 | 0.513–1.837 | 0.928 | 1.473 | 0.665–3.261 | 0.340 |

| Diabetes | 1.673 | 0.683–4.096 | 0.260 | 2.189 | 0.972–4.930 | 0.059 |

| Oral steroids | 0.648 | 0.147–2.852 | 0.566 | 2.665 | 0.582–12.200 | 0.207 |

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 0.703 | 0.158–3.116 | 0.642 | 2.227 | 0.485–10.231 | 0.303 |

| Glaucoma eye drops | 0.685 | 0.274–1.709 | 0.417 | 1.898 | 0.677–5.325 | 0.223 |

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 0.954 | 0.465–1.957 | 0.898 | 0.749 | 0.328–1.714 | 0.494 |

| Surgical history in other departments | 1.089 | 0.326–3.639 | 0.889 | 0.349 | 0.046–2.621 | 0.306 |

|

c. Enterococcus faecalis |

d.Gram-negative bacilli |

|||||

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 1.077 | 1.029–1.128 | 0.002** | 1.026 | 0.991–1.062 | 0.144 |

| Sex (male) | 0.795 | 0.387–1.631 | 0.531 | 1.098 | 0.609–1.981 | 0.756 |

| Hypertension | 0.891 | 0.443–1.793 | 0.747 | 1.355 | 0.735–2.497 | 0.330 |

| Diabetes | 1.682 | 0.753–3.758 | 0.205 | 1.496 | 0.755–2.967 | 0.249 |

| Oral steroids | 0.882 | 0.114–6.806 | 0.904 | 3.294 | 1.071–10.134 | 0.038* |

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 1.468 | 0.326–6.610 | 0.617 | 4.745 | 1.778–12.665 | 0.002** |

| Glaucoma eye drops | 0.772 | 0.225–2.651 | 0.680 | 0.752 | 0.258–2.188 | 0.600 |

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 0.954 | 0.444–2.050 | 0.903 | 1.074 | 0.553–2.086 | 0.834 |

| Surgical history in other departments | 1.372 | 0.464–4.061 | 0.567 | 1.604 | 0.649–3.964 | 0.306 |

|

e. Corynebacterium species |

f. MS-CNS |

|||||

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 1.042 | 1.027–1.057 | 0.000** | 0.993 | 0.978–1.008 | 0.355 |

| Sex (male) | 1.410 | 1.080–1.841 | 0.012* | 1.580 | 1.163–2.147 | 0.003** |

| Hypertension | 1.180 | 0.901–1.545 | 0.230 | 1.114 | 0.810–1.533 | 0.507 |

| Diabetes | 0.948 | 0.684–1.313 | 0.747 | 1.125 | 0.777–1.630 | 0.532 |

| Oral steroids | 1.121 | 0.525–2.392 | 0.768 | 0.725 | 0.270–1.946 | 0.523 |

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 1.196 | 0.570–2.509 | 0.636 | 0.951 | 0.380–2.382 | 0.915 |

| Glaucoma eye drops | 0.457 | 0.288–0.727 | 0.001** | 0.621 | 0.346–1.114 | 0.110 |

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 1.100 | 0.818–1.479 | 0.530 | 0.935 | 0.665–1.316 | 0.701 |

| Surgical history in other departments | 1.148 | 0.705–1.868 | 0.579 | 0.495 | 0.248–0.988 | 0.046* |

|

g. MR-CNS |

||||||

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | ||||

| Age | 1.004 | 0.984–1.025 | 0.667 | |||

| Sex (male) | 0.970 | 0.660–1.425 | 0.877 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.010 | 0.683–1.492 | 0.961 | |||

| Diabetes | 1.111 | 0.699–1.766 | 0.656 | |||

| Oral steroids | 3.651 | 1.628–8.185 | 0.002** | |||

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 1.922 | 0.788–4.685 | 0.151 | |||

| Glaucoma eye drops | 1.209 | 0.671–2.178 | 0.528 | |||

| Visit history to ophthalmic facilities | 1.650 | 1.032–2.639 | 0.037* | |||

| Surgical history in other departments | 2.800 | 1.592–4.923 | 0.000** | |||

Logistic regression analysis.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococci and Enterococcus faecalis showed a significant association with age in univariate analysis (P=0.008 and P=0.001, respectively; Tables 2b and c), and age was a risk factor of alpha-hemolytic streptococci and Enterococcus faecalis in multivariate logistic regression analysis (P=0.044 and P=0.002, respectively; Tables 3b and c). The adjusted odds ratio for 1 additional year of age in alpha-hemolytic Streptococci and Enterococcus faecalis was 1.049 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.001–1.100) and 1.077 (95% CI, 1.029–1.128), respectively.

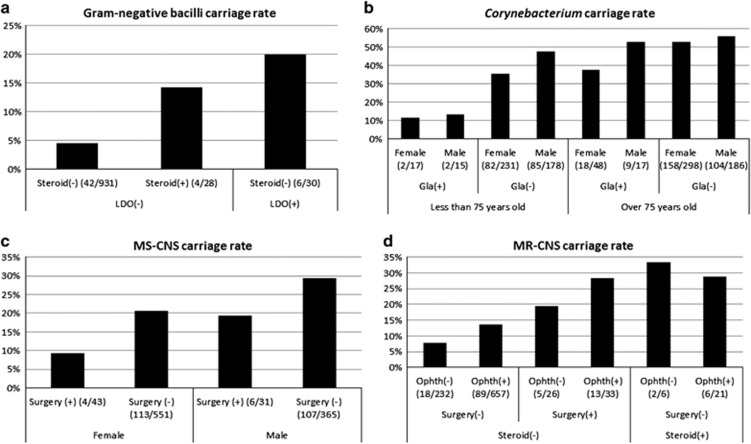

Gram-negative bacilli showed a significant association with lacrimal duct obstruction in univariate analysis (P=0.004; Table 2d). In addition to lacrimal duct obstruction, oral steroid use was also a risk factor in multivariate logistic regression analysis (P=0.038 and P=0.002, respectively; Table 3d). The adjusted odds ratio was 3.294 for oral steroid use (95% CI, 1.017–10.134) and 4.745 for lacrimal duct obstruction (95% CI, 1.778–12.665). These two factors increased the carriage rate, and the carriage rate of gram-negative bacilli was increased up to 20.0% from 4.5% depending on the two factors (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Changes in bacterial carriage rate in conjunctiva. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of carriers. Gla, glaucoma eye drops; LDO, lacrimal duct obstruction; Ophth, visit history to ophthalmic facilities; Surgery, surgical history in other departments. (a) Gram-negative bacilli carriage rate varied depending on Steroid and LDO. (b) Corynebacterium carriage rate varied depending on sex, Gla and age. (c) MS-CNS carriage rate varied depending on Surgery and sex. (d) MR-CNS carriage rate varied depending on Ophth, Surgery and Steroid.

Corynebacterium species showed a significant association with age, male sex, hypertension and glaucoma eye drop use in univariate analysis (P<0.001, P=0.044, P=0.015 and P=0.003, respectively; Table 2e). These factors, except for hypertension, were risk factors in multivariate logistic regression analysis (P<0.001, P=0.012 and P=0.001, respectively; Table 3e). The adjusted odds ratio for 1 additional year of age was 1.042 (95% CI, 1.027–1.057), and the adjusted odds ratio for men was 1.410 (95% CI, 1.080–1.841); these two factors increased the carriage risk. The adjusted odds ratio for glaucoma eye drop use was 0.457 (95% CI, 0.288–0.727); thus, it decreased the carriage risk. The carriage rate of Corynebacterium species varied from 11.8 to 55.9% depending on these three factors (Figure 1b).

MS-CNS showed a significant association with sex in univariate analysis (P=0.001) (Table 2f). Surgical history in other departments along with the male sex were risk factors in multivariate logistic regression analysis (P=0.003 and P=0.046, respectively) (Table 3f). The adjusted odds ratio for the male sex was 1.580 (95% CI, 1.163–2.147), and the adjusted odds ratio for surgical history in other departments was 0.495 (95% CI, 0.248–0.988). The carriage rate of MS-CNS varied from 9.3 to 29.3% depending on these two factors (Figure 1c).

MR-CNS showed a significant association with oral steroid use, visit history to ophthalmic facilities and surgical history in other departments (P=0.003, P=0.036 and P=0.001, respectively; Table 2g). Oral steroid use, visit history to ophthalmic facilities and surgical history in other departments were risk factors in multivariate logistic regression analysis (P=0.002, P=0.037 and P<0.001, respectively; Table 3g). The adjusted odds ratios were 3.651 (95% CI, 1.628–8.185) for oral steroid use, 1.650 (95% CI, 1.032–2.639) for visit history to ophthalmic facilities and 2.800 (95% CI, 1.592–4.923) for surgical history in other departments. These 3 factors increased the carriage rate, and the MR-CNS carriage rate varied from 7.8 to 33.3% depending on these three factors (Figure 1d).

Discussion

With respect to the carriage of alpha-hemolytic streptococci and Enterococcus faecalis, age was a risk factor. Acute postoperative endophthalmitis due to Enterococcus faecalis and alpha-hemolytic streptococci has a poor prognosis.13, 14 In our results, in patients over the age of 80 years, the conjunctival detection rate of each species was >5%. Therefore, in cases of serious postoperative endophthalmitis in elderly patients, the possibility of infection due to enterococci and streptococci should be considered.

With respect to the carriage of gram-negative bacilli, oral steroid use and lacrimal duct obstruction were independent risk factors. Many gram-negative bacilli detected in our study were bacteria inhabiting the humid environment. Conjunctivitis caused by Haemophilus species is seasonal in nature. However, because there was a small number of these species, features of the gram-negative bacilli group in our study would not represent the characteristics of Haemophilus species alone. It was suggested that the immune system function needed to eliminate environmental bacteria from the conjunctiva is diminished among patients who use oral steroids. Miller and Ellis9 reported a positive correlation between the dose of prednisolone and the number of bacterial isolates from conjunctiva. Therefore, it is believed that immunosuppressed patients can be easily infected by environmental bacteria. The relevance of lacrimal duct obstruction and gram-negative bacilli is easily understood, because gram-negative bacilli grow easily in stagnant tears unable to flow through the blocked duct. To control infection in intraocular surgery, it is important to consider that bacterial conjunctival flora may be changed among mild lacrimal duct obstruction patients without remarkable clinical findings. Kam et al15 reported that the incidence of postcataract endophthalmitis among nasolacrimal duct obstruction patients was significantly higher than in the control group. Therefore, it is preferable to confirm the lacrimal duct obstruction prior to intraocular surgery regardless of epiphora. If lacrimal duct obstruction is present, it is preferable to wash the lacrimal duct just before cataract surgery, or if possible, to perform lacrimal duct reconstruction before cataract surgery.

With respect to the carriage of Corynebacterium species, age, male sex and glaucoma eye drop use were independent risk factors. The male sex and increased age increased the risk of conjunctival carriage of Corynebacterium, but glaucoma eye drop use decreased the risk of conjunctival carriage. Fernández-Rubio et al8 reported that increased age and the male sex were associated with the Corynebacterium detection rate in conjunctiva. Corynebacterium grows easily in lipid-rich environments.16 Therefore, it is possible that the amount or properties of lipids in the ocular surface of male patients and elderly patients are convenient for the growth of Corynebacterium. It is unclear why the detection rate of Corynebacterium was reduced by glaucoma eye drop use. The conjunctival detection rate of Corynebacterium in preoperative glaucoma patients was significantly decreased as compared to preoperative cataract patients.17 Because preoperative glaucoma patients should have used glaucoma eye drops, our result might be consistent with this previous report. However, it has also been reported that the use of glaucoma eye drops did not affect the bacterial detection rate.18 Therefore, the influence of glaucoma eye drops on the detection rate of Corynebacterium requires further study.

The proportion of CNS in our study is quite different from that of these bacteria in Europe or the United States. The length of the incubation period is considered to be one of the causes. In the case of 7–10 days of culture period, the proportion of CNS is 64.7–74.0%.6, 9, 17 On the other hand, the incubation period is 2 days in previous Japanese papers, and the proportion of CNS is 24.7–57.2%.4, 7 These Japanese data are similar to our data (35.5%). The risk factors for CNS were different according to the presence or absence of methicillin resistance. First, in MS-CNS, the male sex and surgical history in other departments were independent risk factors. The MS-CNS conjunctival carriage rate was increased in men. Fernández-Rubio et al8 reported that the male sex was one of the risk factor for colonization of CNS in conjunctiva. Although the reason is unclear, as in the case of Corynebacterium, it is possible that the lipids necessary for the growth of MS-CNS are more abundant in men. In MR-CNS, oral steroid use, visit history to ophthalmologic facilities and surgical history in other departments were independent risk factors. As in the case of gram-negative bacilli, it may be considered that MR-CNS in the conjunctiva is difficult to eliminate in the immunocompromised state caused by systemic steroids. It has not been previously reported that MR-CNS in conjunctiva is associated with visit history to ophthalmic facilities or surgical history in other departments. Our results suggest that MR-CNS conjunctival carriage is strongly affected by healthcare-associated infection. Moreover, the reduction of MS-CNS and the increase of MR-CNS in patients with surgical history appear to be two sides of the same coin. Many surgical patients receive systemic antibiotics in the perioperative period. As a result, the patients affected by antibiotics may be susceptible to MR-CNS infection. Moreover, MR-CNS could be spread to other patients by physical contact with medical staff in ophthalmic facilities. Therefore, the ophthalmologist must strictly adhere to infection prevention measures to prevent MR-CNS infection among ophthalmic patients. Hand hygiene by alcohol antiseptic or hand washing before contact with the patient's eye is critically important.

With respect to the carriage of Staphylococcus aureus, there were no statistically significant risk factors in preoperative cataract patients. A high detection rate of Staphylococcus aureus in the conjunctiva in atopic dermatitis patients was previously reported.10 In the present study, we could not perform a statistical analysis of patients with atopic dermatitis because the number of patients with atopic dermatitis was too small (nine cases). Staphylococcus aureus primarily inhabits the nasal vestibule, and about 30% of people have asymptomatic colonization in the nasal vestibule.19 Alexandrou et al20 reported that prophylactic use of mupirocin nasal ointment significantly reduced the bacterial detection rate in conjunctiva. Therefore, it is possible that nasal Staphylococcus aureus colonization affects conjunctival bacterial flora.

The limitations of our study are that some patient background factors, such as atopic dermatitis, autoimmune disease and use of immunosuppressive agents other than steroids, could not be considered because the numbers of patients with these factors were too small. A high detection rate of conjunctival bacteria among patients with systemic disease has been previously reported.6, 8 The reason why diabetes was not a risk factor in our study is unknown. In an epidemiological study of Japan (the Hisayama study), the prevalence of diabetes at 40–79 years was 24.0% for men and 13.4% for women.21 Since the prevalence of diabetes in our study was 20.8%, our result was similar to that of the Hisayama study. Although diabetes was not a risk factor in our study, there are several reports that diabetes increases the conjunctival bacterial detection rate.8, 11, 12 Therefore, care must be taken when performing surgery on patients with severe systemic disease. In addition, it is necessary to further study the risk factors of anaerobic bacteria, such as Propionibacterium acnes, which cause late-onset endophthalmitis.

In conclusion, preoperative cataract patients had different risk factors for each type of conjunctival bacteria. Elderly patients, men, patients with lacrimal duct obstruction or immunosuppressed patients were most likely to be colonized by pathogens causing postoperative endophthalmitis. In particular, MR-CNS conjunctival carriage was associated with healthcare-associated infection. To prevent the spread of MR-CNS in ophthalmologic departments, the strict observance of standard precautions is critically important.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bannerman TL, Rhoden DL, McAllister SK, Miller JM, Wilson LA. The source of coagulase-negative Staphylococci in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. A comparison of eyelid and intraocular isolates using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115: 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Engelbert M, Parke DW 2nd, Jett BD, Gilmore MS. Bacterial endophthalmitis: epidemiology, therapeutics, and bacterium-host interactions. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15: 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchia FM, Busbee BG, Pearlman RB, Carvalho-Recchia CA, Ho AC. Changing trends in the microbiologic aspects of postcataract endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2005; 123: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y, Nakazawa T, Maeda N, Sakamoto M, Yokokura S, Kubota A et al. Susceptibility comparisons of normal preoperative conjunctival bacteria to fluoroquinolones. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009; 35: 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio EF. Influence of age on conjunctival bacteria of patients undergoing cataract surgery. Eye (Lond) 2006; 20: 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miño De, Kaspar H, Ta CN, Froehlich SJ, Schaller UC, Engelbert M, Klauss V et al. Prospective study of risk factors for conjunctival bacterial contamination in patients undergoing intraocular surgery. Eur J Ophthalmol 2009; 19: 717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto C, Morinaga M, Yagi T, Tsuji C, Toshida H. Conjunctival sac bacterial flora isolated prior to cataract surgery. Infect Drug Resist 2012; 5: 37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rubio ME, Cuesta-Rodríguez T, Urcelay-Segura JL, Cortés-Valdés C. Pathogenic conjunctival bacteria associated with systemic co-morbidities of patients undergoing cataract surgery. Eye (Lond) 2013; 27: 915–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Ellis PP. Conjunctival flora in patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs. Arch Ophthalmol 1977; 95: 2012–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata K, Inoue Y, Harada J, Maeda N, Watanabe H, Tano Y et al. A high incidence of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in the external eyes of patients with atopic dermatitis. Ophthalmology 2000; 107: 2167–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins EN, Alvarenga LS, Höfling-Lima AL, Freitas D, Zorat-Yu MC, Farah ME et al. Aerobic bacterial conjunctival flora in diabetic patients. Cornea 2004; 23: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rubio ME, Rebolledo-Lara L, Martinez-García M, Alarcón-Tomás M, Cortés-Valdés C. The conjunctival bacterial pattern of diabetics undergoing cataract surgery. Eye (Lond) 2010; 24: 825–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan AE, Sridhar J, Flynn Jr HW, Smiddy WE, Albini TA, Berrocal AM et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Enterococcus faecalis: clinical features, antibiotic sensitivities, and outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 158: 1018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan AE, Weiss KD, Flynn Jr HW, Smiddy WE, Berrocal AM, Albini TA et al. Endophthalmitis caused by streptococcal species: clinical settings, microbiology, management, and outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157: 774–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam JK, Cheng NM, Sarossy M, Allen PJ, Brooks AM. Nasolacrimal duct screening to minimize post-cataract surgery endophthalmitis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2014; 42: 447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel P, Ruimy R, de Briel D, Prévost G, Jehl F, Christen R et al. Genomic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among lipid-requiring diphtheroids from humans and characterization of Corynebacterium macginleyi sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995; 45: 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kaspar HM, Kreidl KO, Singh K, Ta CN. Comparison of preoperative conjunctival bacterial flora in patients undergoing glaucoma or cataract surgery. J Glaucoma 2004; 13: 507–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen EM, Yilmaz MB, Dansuk Z, Aksakal FN, Altinok A, Tuna T et al. Effect of chronic topical glaucoma medications on aerobic conjunctival bacterial flora. Cornea 2009; 28: 266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5: 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrou TJ, Hariprasad SM, Benevento J, Rubin MP, Saidel M, Ksiazek S et al. Reduction of preoperative conjunctival bacterial flora with the use of mupirocin nasal ointment. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2006; 104: 196–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai N, Doi Y, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa Y, Nagata M, Yoshida D et al. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in community-dwelling Japanese subjects: The Hisayama Study. J Diabetes Investig 2014; 5: 162–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]