Abstract

One of the most commonly used complementary and alternative practices in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is the supplementation of omega-3. We describe the case of a child with ASD who seemed to respond to omega-3 supplementation in a relevant and lasting manner. So far, based on the results of randomized clinical trials, evidence-based medicine negates the effectiveness of omega-3 in ASD children. Nevertheless, considering anecdotal experiences, including that of our patient, and nonrandomized trials, the presence of a subgroup of ASD patients who are really responders to omega-3 cannot be excluded. These responders might not appear when evaluating the omega-3 effects in a sample taken as a whole. Studies that check for the possible presence of this subgroup of ASD individuals responders to omega-3 are necessary.

Key words: Autism spectrum disorders, complementary and alternative medicine, essential fatty acids, neurobiology, omega-3

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD), according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5), are neurodevelopmental pathologies impairing both social competencies and patterns of behavior.[1] Until today, conventional medicine has not provided a curative treatment for ASD. It is probably also for this reason that in the last decades complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has spread widely among families of ASD children,[2] although apart from melatonin, there is no scientific evidence of their effectiveness.[3] One of the most commonly used CAM practices in ASD children is the supplementation of omega-3[3] that are essential fatty acids present in the following foods: fish, seafood, meat, eggs, vegetable oils, cereal-based products.[4]

We describe the case of a child with ASD who seemed to respond to omega-3 supplementation in a relevant and lasting manner.

Case Report

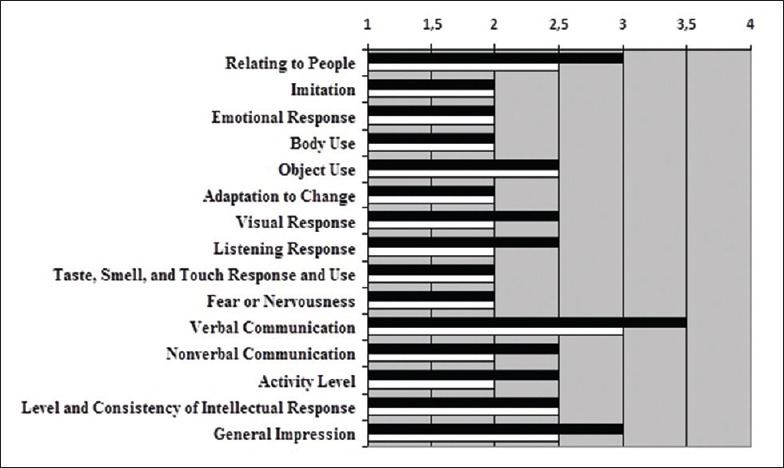

Male, aged 6 years 9 months. Family history was positive for ASD in two first-degree paternal cousins; previous language delay in the paternal line. He was born at full term, from uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery. Psychomotor development was normal except for a language delay. The boy came to our observation for the first time at the age of 2 years 10 months. Already at that time, there were qualitative anomalies in terms of intersubjectivity (limited exchange capacity), communication (lacking both the verbal and nonverbal), and interests (perseverative activities such as hitting objects against each other), so as to justify a diagnosis of ASD, according to the DSM-5 criteria.[1] Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 1, showed an overall result above the cutoff for autism, with a score above the cutoff for autism in language and communication, as well as in reciprocal social interaction. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale 2nd Edition – Standard Version (CARS2-ST) showed results consistent with mild to moderate symptoms of ASD (see later). Leiter-R scale showed a nonverbal intelligence quotient = 97 (normal). His behavior was hyperactive and oppositional, while attention was lacking. Neurological examination was negative. Chromosomal microarray was normal, as well as electroencephalogram in sleep deprivation. After obtaining an informed consent, at the age of 4 years 11 months an oral treatment with omega-3 at the dosage of 1 g a day was started. Since then, significant improvements were observed in the clinical picture. The child appeared more active and responsive to solicitations, verbal (comprehension and expression) and nonverbal communication skills increased, personal autonomy improved, oppositional behaviors as well as hyperactivity and inattention decreased. These improvements have been quantified through CARS2-ST [Figure 1]: while the total score was 36.5 (cutoff for the presence of mild to moderate symptoms of ASD = 30) before omega-3 treatment start, it decreased to 33 at the most recent assessment, 22 months after omega-3 treatment start. According to CARS2-ST, improvement of scores involved the following items: relating to people; visual and listening response; verbal and nonverbal communication; activity level; and general impression [Figure 1]. Therefore, omega-3 supplementation seemed to have a favorable impact on the quality of life of the child. It should be noted that the applied behavior analysis intervention, already underway when the treatment with omega-3 was started, was not subsequently modified. No other behavioral/pharmacological intervention was carried out during the treatment with omega-3. Various attempts to suspend the omega-3 supplementation during the 22 months of follow-up failed because of significant symptom worsening (restlessness, agitation, decrease of responsiveness to teaching), which then disappeared after the resumption of the treatment. There were no side effects attributable to omega-3. At the time of the most recent evaluation, at the age of 6 years and 9 months, the child was still taking oral omega-3 supplementation.

Figure 1.

Profile of the scores of the 15 items included in the Childhood Autism Rating Scale, 2nd Edition – Standard Version, respectively before (black horizontal bars) and 22 months after (white horizontal bars) the start of omega-3 treatment. Note that Score 1 corresponds to the normal behavior, while Score 4 corresponds to the most atypical behavior

Discussion

The interesting hypothesis of Van Elst et al. seems to be a good theoretical basis for treatment with omega-3 supplementation in children with ASD. They speculated that the increase in ASD prevalence during the last decades is related to dietary modifications of fatty acid composition, characterized by a higher ratio omega-6/omega-3. In particular, the omega-3 deficit, especially in the early stages of life, may cause changes of myelination, neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, neurotransmitter turnover, brain connectivity, cellular differentiation and development, inflammatory reactions, cognitive functioning, and behavior. These changes are all hypothetically involved in ASD etiopathogenesis.[5]

But so far, based on the results of randomized clinical trials, evidence-based medicine negates the effectiveness of omega-3 in ASD children in particular on symptoms such as deficits in social interaction and communication, hyperactivity, stereotypies.[6,7,8,9] The empirical value of a case report like ours is obviously not comparable to that of a randomized clinical trial, primarily due to the risk of mistakenly considering a placebo effect as a real effect of the drug. We were aware of this possible bias when describing our case. Nevertheless, considering anecdotal experiences, including that of our patient, and nonrandomized trials,[10,11] the presence of a subgroup of ASD patients who are really responders to omega-3 cannot be excluded. These responders might not appear when evaluating the omega-3 effects in a sample taken as a whole.[12] Further, considering the high heterogeneity of ASD phenotypes and etiologies, it seems to be very unlikely that a given treatment produces the same results in all affected individuals.[13]

Conclusion

We believe that the question about the effectiveness of omega-3 in ASD is still open and that it requires carrying out studies that check for the possible presence of a subgroup of ASD individuals responders to this treatment. Should the actual presence of these responders be determined, it would surely be very important to identify what the characteristics are that distinguish them from nonresponders.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Cecilia Baroncini for linguistic support.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. (DSM-) 5th Ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akins RS, Angkustsiri K, Hansen RL. Complementary and alternative medicine in autism: An evidence-based approach to negotiating safe and efficacious interventions with families. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:307–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehouse AJ. Complementary and alternative medicine for autism spectrum disorders: Rationale, safety and efficacy. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:E438–42. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer BJ, Mann NJ, Lewis JL, Milligan GC, Sinclair AJ, Howe PR. Dietary intakes and food sources of omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipids. 2003;38:391–8. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Elst K, Bruining H, Birtoli B, Terreaux C, Buitelaar JK, Kas MJ. Food for thought: Dietary changes in essential fatty acid ratios and the increase in autism spectrum disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45:369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James S, Montgomery P, Williams K. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation for autism spectrum disorders (ASD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD007992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007992.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bent S, Hendren RL, Zandi T, Law K, Choi JE, Widjaja F, et al. Internet-based, randomized, controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids for hyperactivity in autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:658–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voigt RG, Mellon MW, Katusic SK, Weaver AL, Matern D, Mellon B, et al. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in children with autism. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:715–22. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mankad D, Dupuis A, Smile S, Roberts W, Brian J, Lui T, et al. A randomized, placebo controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of young children with autism. Mol Autism. 2015;6:18. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0010-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson SM, Hollander E. Evidence that eicosapentaenoic acid is effective in treating autism. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:848–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0718c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ooi YP, Weng SJ, Jang LY, Low L, Seah J, Teo S, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in the management of autism spectrum disorders: Findings from an open-label pilot study in Singapore. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:969–71. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posar A, Visconti P. Complementary and alternative medicine in autism: The question of omega-3. Pediatr Ann. 2016;45:e103–7. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20160129-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bölte S. Is autism curable? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:927–31. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]