Abstract

Background and objectives

Although patients with CKD are commonly hospitalized, little is known about those with frequent hospitalization and/or longer lengths of stay (high inpatient use). The objective of this study was to explore clinical characteristics, patterns of hospital use, and potentially preventable acute care encounters among patients with CKD with at least one hospitalization.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We identified all adults with nondialysis CKD (eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) in Alberta, Canada between January 1 and December 31, 2009, excluding those with prior kidney failure. Patients with CKD were linked to administrative data to capture clinical characteristics and frequency of hospital encounters, and they were followed until death or end of study (December 31, 2012). Patients with one or more hospital encounters were categorized into three groups: persistent high inpatient use (upper 5% of inpatient use in 2 or more years), episodic high use (upper 5% in 1 year only), or nonhigh use (lower 95% in all years). Within each group, we calculated the proportion of potentially preventable hospitalizations as defined by four CKD–specific ambulatory care sensitive conditions: heart failure, hyperkalemia, volume overload, and malignant hypertension.

Results

During a median follow-up of 3 years, 57,007 patients with CKD not on dialysis had 118,671 hospitalizations, of which 1.7% of patients were persistent high users, 12.3% were episodic high users, and 86.0% were nonhigh users of hospital services. Overall, 24,804 (20.9%) CKD–related ambulatory care sensitive condition encounters were observed in the cohort. The persistent and episodic high users combined (14% of the cohort) accounted for almost one half (45.5%) of the total ambulatory care sensitive condition hospitalizations, most of which were attributed to heart failure and hyperkalemia. Risk of hospitalization for any CKD–specific ambulatory care sensitive condition was higher among older patients, higher CKD stage, lower income, registered First Nations status, and those with poor attachment to primary care.

Conclusions

Many hospitalizations among patients with CKD and high inpatient use are ambulatory care sensitive condition related, suggesting opportunities to improve outcomes and reduce cost by focusing on better community–based care for this population.

Keywords: chronic renal insufficiency; heart failure; adult; Alberta; Ambulatory Care; Canada; follow-up studies; hospitalization; humans; Hyperkalemia; Hypertension, Malignant; Inpatients; Primary Health Care; renal dialysis; renal insufficiency, chronic; Residence Characteristics

Introduction

CKD affects approximately 10% of the adult population and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (1–5). Prior studies have also observed high rates of hospitalization and substantial health care costs among patients with CKD (6–9). As health care expenditures continue to rise in Canada (10), policymakers have the difficult task of developing strategies that reduce costs but improve quality of care. A potential strategy has been to focus on high-risk patients who account for the majority of health care costs and often experience poor clinical outcomes (11–14).

Better coordination and management of chronic conditions, like CKD, in the outpatient setting may meet health care needs and reduce the risk of hospitalization (15–17)—which in turn, would free up scarce hospital resources, lower the cost of care, and improve patient experience and outcomes (a framework for optimizing health system performance referred to as the Triple Aim by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement) (18). However, this assumes that some of the inpatient utilization among patients with CKD is potentially preventable. Although prior studies suggested that a small proportion of hospital encounters may be ambulatory care sensitive (approximately 10%) among patients with CKD (19), this has not been explored among the subset of patients with highest resource use.

Given the high burden of comorbid illness among patients with CKD (20) combined with the known economic effect of CKD (6–9), it seems important to better understand the characteristics of patients who are frequent users of inpatient services. Using a large population–based database, we aimed to explore the clinical and demographic characteristics of these high-risk patients, how they use inpatient services over time, and the proportion of inpatient utilization that is potentially preventable. This information is a necessary first step to identify potential interventions that might reduce inpatient utilization and improve health outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

This study was undertaken using a previously described provincial laboratory repository—the Alberta Kidney Disease Network (21). We identified a cohort of all adults (≥18 years old) with nondialysis CKD between January 1 and December 31, 2009 and at least one hospitalization in the subsequent 3 years in Alberta, Canada. CKD status was defined on the basis of the patient’s first outpatient serum creatinine measurement in 2009 that equated to an eGFR of 15–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation (22). Patients with CKD were then linked to administrative data obtained from the provincial health ministry to capture clinical characteristics and frequency of hospital encounters. We followed all patients with CKD from the index date (first serum creatinine measurement that defined CKD status) to death or end of study (December 31, 2012). Patients with CKD and at least one hospitalization in the study period were included in the final cohort. We excluded individuals with preexisting kidney failure as defined by eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, those undergoing dialysis, or those with a kidney transplant before the index date because of inherent differences in their health status and system usage (23,24).

Identification of High Users of Inpatient Services

For each patient with CKD, the number of hospital encounters was recorded for each year of follow-up. Patients with at least three hospital encounters in a given year of follow-up were considered to be high users (approximately upper fifth percentile of inpatient use) (25,26). A patient’s hospital use over the entire follow-up period was then categorized into three groups: (1) episodic high use: high user in 1 year of follow-up only; (2) persistent high use: high user in at least 2 years within the study follow-up period; and (3) nonhigh use: the lower 95% of hospital use for each year of follow-up.

Clinical Characteristics and Resource Utilization

We identified clinical characteristics and additional measures of health system utilization for the cohort as well as high-use categories. Variables of interest were on the basis of the Andersen Health Behavior Model, a framework for understanding the different enabling, predisposing, and provider-/system-level factors that affect health care utilization (27). Patient-level characteristics included age, sex, population type (registered First Nations status, health care subsidy, income support, pensioners, and general population), urban/rural status, and median neighborhood income quintile. CKD stage was estimated using the CKD-EPI equation on the basis of the index serum creatinine (22). The presence of 27 comorbidities was ascertained on the basis of individual validated International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems, Ninth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-9/ICD-10) coding algorithms (28). These comorbidities were also grouped on the basis of their relationship to CKD. Specifically, conditions that share similar pathophysiologic risk profiles were defined as concordant conditions (29). Conditions that were not similar in their pathogenesis were defined as discordant, and mental health conditions were categorized separately. Detailed information for each algorithm, including ICD-9/ICD-10 codes, data sources, and lookback windows to defined conditions, is available in Supplemental Appendix 1. Physician attachment was defined as the proportion of all outpatient primary care visits made to a single practitioner in the 2-year period before first hospitalization (among those with at least three primary care visits). This was categorized as 100%–75% (good attachment), 74%–50% (moderate attachment), or <50% (low attachment) (30,31). We also identified the proportion of patients with at least one nephrologist visit in the 2-year period before first hospitalization. Finally, we identified characteristics related to hospital encounters, including the average length of stay per encounter, total number of hospital encounters and total hospital days accumulated over the study period for each high–cost category, and discharge disposition of the last admission in the follow-up period. Overall mortality (measured as proportions and rates [deaths per 1000 patient-years]) within the follow-up period and all–cause 30-day readmissions were also measured.

Identification of Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations

Potentially preventable hospitalization was defined as an inpatient encounter for an ambulatory care sensitive condition (ACSC). ACSCs are health conditions for which good outpatient care can likely prevent the need for hospitalization and recognized internationally as a measure of adequacy of ambulatory and primary health care performance (32–34). Four CKD-specific ACSCs, including hyperkalemia, malignant hypertension, heart failure, and volume overload, were identified using previously defined ICD-10 coding algorithms. These were developed using a Delphi technique and have been used to identify ACSCs in patients with CKD in prior studies (19,35). The key difference between heart failure and volume overload as assessed by these coding algorithms is that the latter comprises extracellular fluid volume expansion that is not judged to be attributable directly to poor cardiac function.

Analyses

Patient characteristics were described using proportions and means (SD) where appropriate for the entire cohort and each of the high-use categories. Hospital encounter characteristics were reported in each high–use category as well as overall as medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs]) or proportions where appropriate. Statistical comparisons of patient and encounter characteristics across high-use groups were also performed. Analysis of potentially preventable hospitalization (ACSCs) was done at both the encounter and patient levels for the entire cohort and by high-use category. This included the proportion of all hospital encounters that involved a CKD-specific ACSC, the proportion of all patients who had at least one CKD–specific ACSC hospitalization, and the proportion of patients with each of the four CKD–specific ACSC conditions.

We used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors independently associated with high user status (episodic and persistent use combined). Initially, we conducted bivariate analyses and produced univariate odds ratios (ORs) for each potential predictor. We then developed a full multivariable logistic regression model including all clinical characteristics and measures of health system utilization and used manual backward elimination with a significance level of P<0.05 to form a parsimonious model of the strongest predictors of high user status. We then used similar modeling techniques to identify factors associated with the risk of a CKD-specific ACSC among high users of inpatient services (episodic and persistent use combined). Within this model, the outcome was at least one ACSC hospitalization during the follow-up period among high users of inpatient services. In all models, adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) are reported. All analyses were conducted using STATA 12 (StataCorp., College Station, TX). The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary approved this study and granted waiver of patient consent.

Results

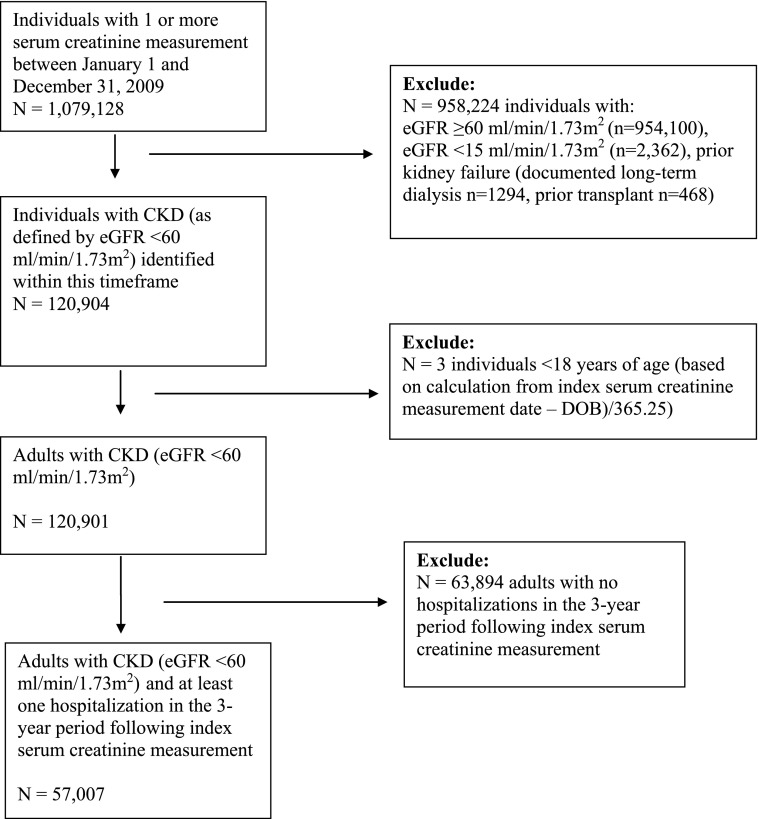

In total, 1,079,128 individuals had one or more outpatient serum creatinine measurement between January 1 and December 31, 2009. After excluding individuals <18 years of age, those with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and those with prior kidney failure or transplant, we identified 120,901 patients with CKD. Of these patients, 63,894 did not have a hospital encounter in the 3-year follow-up period, leaving a final cohort of 57,007 patients with CKD and at least one hospitalization (Figure 1). The mean age (SD) of the cohort was 76.3 (11.6) years old, and 43.1% were men (Table 1). Within this cohort, 1.7% of patients were classified as persistent high inpatient users of hospital services, 12.3% were episodic high users, and 86.0% were nonhigh users. Persistent high users were often younger (lower overall mean age and higher proportion of patients in the 18- to 44-year-old age category), men, registered First Nations, and living in rural areas compared with those in episodic and nonhigh-use groups (P<0.001 for all comparisons). Despite younger age, persistent high users were more likely to have more severe CKD, higher levels of comorbidity in general, and a larger proportion of discordant- and mental health–related comorbidities. The proportion of patients with poor primary care attachment (<50% of visits to the same primary care physician) was also higher in persistent high users (32.8%) compared with patients with episodic (24.5%) and nonhigh use (19.0%; P<0.001). Similarly, the proportion of patients with one or more nephrologist visits in the prior 2-year period was higher in persistent high users (24.8%) compared with patients with episodic (18.8%) and nonhigh use (13.0%; P<0.001). These findings were corroborated by our multivariable logistic regression analysis, which identified similar independent risk factors for high user status (Supplemental Appendix 2).

Figure 1.

Criteria to determine the final study cohort. DOB, date of birth.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics by high-use status (n=57,007)

| Patient Characteristics | High User Status | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Persistent | Episodic | Nonhigh Use | ||

| No. of patients, % | 57,007 (100) | 947 (1.7) | 7010 (12.3) | 49,050 (86.0) | |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 76.31 (11.63) | 72.75 (13.46) | 75.96 (11.54) | 76.44 (11.59) | <0.001 |

| Age category, yr | |||||

| 18–44 | 863 (1.5) | 40 (4.2) | 113 (1.6) | 710 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 8193 (14.4) | 192 (20.3) | 1047 (14.9) | 6954 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| 65–74 | 13,141 (23.1) | 239 (25.2) | 1597 (22.8) | 11,305 (23.0) | <0.001 |

| 75+ | 34,810 (61.1) | 476 (50.3) | 4253 (60.7) | 30,081 (61.3) | <0.001 |

| Men | 24,565 (43.1) | 470 (49.6) | 3283 (46.8) | 20,812 (42.4) | <0.001 |

| Population type | |||||

| First Nations status | 955 (1.7) | 68 (7.2) | 214 (3.1) | 673 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Health care subsidy | 1374 (2.4) | 20 (2.1) | 185 (2.6) | 1169 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Income support | 1457 (2.6) | 54 (5.7) | 254 (3.6) | 1149 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Pensioner | 47,381 (83.1) | 689 (72.8) | 5716 (81.5) | 40,976 (83.5) | <0.001 |

| General population | 5840 (10.2) | 116 (12.2) | 641 (9.1) | 5083 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| Location of residence | |||||

| Urban | 40,558 (71.1) | 525 (55.4) | 4381 (62.5) | 35,653 (72.7) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 16,447 (28.9) | 442 (44.6) | 2627 (37.5) | 13,398 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Median neighborhood household income quintile | |||||

| 1, Lowest | 16,140 (28.3) | 311 (32.8) | 2165 (30.9) | 13,664 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 13,476 (23.6) | 231 (24.4) | 1687 (24.1) | 11,558 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 10,677 (18.7) | 173 (18.3) | 1242 (17.7) | 9262 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 7584 (13.3) | 104 (11.0) | 888 (12.7) | 6592 (13.4) | <0.001 |

| 5, Highest | 7388 (13.0) | 87 (9.2) | 799 (11.4) | 6502 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1742 (3.1) | 41 (4.3) | 229 (3.3) | 1472 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| CKD stage | |||||

| 3A, 59–45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 36,062 (63.3) | 526 (55.5) | 4050 (57.8) | 31,486 (64.2) | <0.001 |

| 3B, 44–30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 15,371 (27.0) | 290 (30.6) | 2077 (29.6) | 13,004 (26.5) | <0.001 |

| 4, 29–15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 5574 (9.8) | 131 (13.8) | 883 (12.6) | 4560 (9.3) | <0.001 |

| General practitioner attachment, n=55,944 | |||||

| <50% | 11,146 (19.9) | 306 (32.8) | 1695 (24.5) | 9145 (19.0) | <0.001 |

| 50%–74% | 17,596 (31.5) | 328 (35.1) | 2341 (33.9) | 14,927 (31.0) | <0.001 |

| 75%–100% | 27,202 (48.6) | 300 (32.1) | 2875 (41.6) | 24,027 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| At least one visit with nephrologist in prior 2 years, % | 7924 (13.9) | 235 (24.8) | 1321 (18.8) | 6368 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities of interest | |||||

| Alcoholism | 2396 (4.2) | 123 (13.0) | 428 (6.1) | 1845 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 3735 (6.6) | 136 (14.4) | 639 (9.1) | 2960 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 12,280 (21.5) | 316 (33.4) | 2000 (28.5) | 9964 (20.3) | <0.001 |

| Cancer, lymphoma | 824 (1.4) | 16 (1.7) | 166 (2.4) | 642 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Cancer, metastatic | 1748 (3.1) | 38 (4.0) | 287 (4.1) | 1423 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Cancer, nonmetastatic | 5543 (9.7) | 105 (11.1) | 833 (11.9) | 4605 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 15,956 (28.0) | 469 (49.5) | 2760 (39.4) | 12,727 (25.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pain | 8210 (14.4) | 226 (23.9) | 1212 (17.3) | 6772 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 19,363 (34.0) | 537 (56.7) | 3122 (44.5) | 15,704 (32.0) | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 607 (1.1) | 55 (5.8) | 142 (2.0) | 410 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 5871 (10.3) | 83 (8.8) | 604 (8.6) | 5184 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 7062 (12.4) | 222 (23.4) | 1026 (14.6) | 5814 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 19,371 (34.0) | 473 (49.9) | 2817 (40.2) | 16,081 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Epilepsy | 1270 (2.2) | 46 (4.9) | 216 (3.1) | 1008 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 48,501 (85.1) | 836 (88.3) | 6128 (87.4) | 41,537 (84.7) | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 12,689 (22.3) | 251 (26.5) | 1612 (23.0) | 10,826 (22.1) | 0.001 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1087 (1.9) | 40 (4.2) | 172 (2.5) | 875 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 2202 (3.9) | 73 (7.7) | 315 (4.5) | 1814 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 394 (0.7) | 11 (1.2) | 54 (0.8) | 329 (0.7) | 0.14 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6862 (12.0) | 175 (18.5) | 1077 (15.4) | 5610 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| Parkinson disease | 760 (1.3) | 26 (2.7) | 115 (1.6) | 619 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 436 (0.8) | 24 (2.5) | 78 (1.1) | 334 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3473 (6.1) | 88 (9.3) | 585 (8.3) | 2800 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Psoriasis | 805 (1.4) | 26 (2.7) | 127 (1.8) | 652 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4060 (7.1) | 106 (11.2) | 579 (8.3) | 3375 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 936 (1.6) | 24 (2.5) | 131 (1.9) | 781 (1.6) | 0.02 |

| Stroke | 13,412 (23.5) | 298 (31.5) | 1913 (27.3) | 11,201 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| No. of comorbidities, mean (SD) | 3.78 (2.20) | 5.56 (2.45) | 4.50 (2.30) | 3.63 (2.15) | <0.001 |

| One or more concordant conditionsa | 51,592 (90.5) | 895 (94.5) | 6501 (92.7) | 44,196 (90.1) | <0.001 |

| One or more discordant conditionsb | 36,316 (63.7) | 789 (83.3) | 5064 (72.2) | 30,463 (62.1) | <0.001 |

| One or more mental health conditionsc | 15,575 (27.3) | 441 (46.6) | 2228 (31.8) | 12,906 (26.3) | <0.001 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Conditions included within the concordant category: myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and stroke.

Conditions included within the discordant category: asthma, cancer (nonmetastatic, metastatic, and lymphoma), COPD, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, hyperthyroidism, cirrhosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, dementia, peptic ulcer disease, psoriasis, and epilepsy.

Conditions included within the mental health category: alcoholism, chronic pain, depression, and schizophrenia.

During median follow-up of 3 years (IQR, 2–3), the 57,007 patients with CKD had 118,671 hospitalizations (Table 2). The median number of hospitalizations among patients who were persistent high users was nine (IQR, 7–11) compared with the median numbers in patients with episodic (four; IQR, 3–5) and nonhigh use (one; IQR, 1–2). The persistent and episodic high users combined (14% of the cohort) accounted for 34.3% of hospital events and 30.2% of the cumulative hospital days within the study period. Overall mortality rate was 139.6/1000 patient-years (95% CI, 137.7 to 141.5; 35.7% of patients dying within the study follow-up period) and highest for episodic high users (217.0/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 210.1 to 224.1). Similar trends were observed for in-hospital mortality, with a larger proportion of episodic high users dying in the hospital; 30-day all-cause readmission to hospital was high among the cohort, with 21.3% having at least one readmission in the study follow-up period. This was higher for those identified as persistent high users, with 81.8% having two or more readmissions within 30 days. An exploration of the discharge disposition for all patients found that discharge to home was most common for patients with nonhigh use, whereas disposition to long-term care or home with support services was common among persistent and episodic high–use groups.

Table 2.

Hospital encounter characteristics and outcomes by high-use status (n=57,007)

| Variable | All, n=57,007 | Persistent High Use, n=947 | Episodic High Use, n=7010 | Nonhigh Use, n=49,050 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of hospital encounters (%) | 118,671 | 8913 (7.5) | 31,796 (26.8) | 77,962 (65.7) | |

| No. of hospital admissions per patient, median (IQR) [range] | 1 (1–3) [1–29] | 9 (7–11) [6–29] | 4 (3–5) [3–23] | 1 (1–2) [1–6] | <0.001 |

| Average length of stay, median (IQR) | 11.1 (6–23) | 11.0 (7.7–16.7) | 12.4 (8–20) | 10.75 (5.5–24.8) | <0.001 |

| Cumulative length of stay, median (IQR) [range] | 17 (6–53) [1–7050] | 118 (71–197) [15–2903] | 60 (32–116) [3–3102] | 13 (5–39) [1–7050] | <0.001 |

| Total no. of hospital days (%) | 2,074,316 | 120,427 (5.8) | 506,724 (24.4) | 1,447,165 (69.8) | <0.001 |

| Discharge disposition (last admission) | |||||

| Transfer to acute care | 0.8 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Transfer to long-term care | 11.6 | 13.2 | 13.9 | 11.2 | <0.001 |

| Transfer to other facility | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Home with support services | 16.6 | 18.0 | 16.9 | 16.6 | <0.001 |

| Home | 49.9 | 35.5 | 35.4 | 52.2 | <0.001 |

| Signed out against medical advice | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 19.6 | 29.4 | 30.8 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

| Overall mortality within study follow-up period (%) | 35.7 | 51.9 | 52.4 | 33 | <0.001 |

| Mortality rate, deaths per 1000 patient-yr (95% CI) | 139.6 (137.7 to 141.5) | 190.7 (174.5 to 208.3) | 217.0 (210.1 to 224.1) | 128.1 (126.2 to 130.1) | <0.001 |

| Proportion of patients with one or more all–cause 30-day readmissionsa | 12,128 (21.3) | 895 (94.5) | 5654 (80.7) | 5579 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| No. of all–cause 30-day readmissionsa | |||||

| 0 | 44,879 (78.7) | 52 (5.5) | 1356 (19.3) | 43,471 (88.6) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 8253 (14.5) | 121 (12.8) | 2788 (39.8) | 5344 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥2 | 3875 (6.8) | 774 (81.8) | 2866 (40.9) | 235 (0.5) | <0.001 |

IQR, interquartile range; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Among patients eligible for hospital readmission (excludes patients who died in hospital before discharge).

Table 3 describes the proportion of hospital encounters and numbers of patients with CKD–specific ambulatory care sensitive encounters. Overall, 24,804 (20.9%) CKD–specific ACSC encounters were observed in the cohort. The proportion of ACSC encounters was highest in persistent high users (29.1%) compared with episodic (27.3%) and nonhigh users (17.3%; chi-squared test; P<0.01). Similarly, the persistent and episodic high users combined (n=7957) accounted for almost one half (45.5%) of the total ACSC hospitalizations and 36.5% of the cumulative hospital days attributed to ACSC events. The majority of these encounters were attributed to heart failure and hyperkalemia across all groups. Analysis at the patient level showed that approximately one in four (24.8%) patients had at least one CKD–related ACSC hospitalization. This was significantly higher for persistent high users (64.4%) compared with episodic (48.5%) and nonhigh users (20.6%). Similar trends were observed in the types of ACSC hospitalizations at the patient level. Over one half (58.7%) of persistent high users had one or more hospitalization for heart failure, and 19.0% had one or more hospitalization for hyperkalemia during study follow-up.

Table 3.

CKD–specific ambulatory care sensitive condition hospitalizations by high-use status

| Encounter- and Patient-Level Characteristic | All, n=57,007 | Persistently High Use, n=947 | Episodic High Use, n=7010 | Nonhigh Use, n=49,050 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encounter-level analysis | ||||

| Total no. of hospital encounters | 118,671 | 8913 | 31,796 | 77,962 |

| Total no. of ACSC encounters regardless of type (proportion of all hospital encounters) | 24,804 (20.9) | 2593 (29.1) | 8681 (27.3) | 13,530 (17.3) |

| Proportion of all ACSC encounters, n=24,804 | 100 | 10.5 | 35.0 | 54.5 |

| Cumulative length of stay of ACSC encounters, median (IQR) | 20 (9–48) | 47.5 (20–91) | 32 (15–66) | 16 (7–39) |

| Total no. of hospital days for ACSC encounters, proportion of total (%) | 830,841 (100) | 58,102 (7.0) | 244,987 (29.5) | 527,752 (63.5) |

| Heart failure encounters | 22,954 (19.3) | 2412 (27.1) | 8124 (25.6) | 12,418 (15.9) |

| Hyperkalemia encounters | 2517 (2.1) | 255 (2.9) | 796 (2.5) | 1466 (1.9) |

| Volume overload encounters | 419 (0.4) | 51 (0.6) | 133 (0.4) | 235 (0.3) |

| Malignant hypertension encounters | 52 (0.0) | 5 (0.1) | 10 (0.0) | 37 (0.1) |

| Patient-level analysis | ||||

| Proportion of patients with at least one ACSC hospitalization regardless of type | 14,131 (24.8) | 610 (64.4) | 3397 (48.5) | 10,124 (20.6) |

| Proportion of patients with an ACSC encounter related to heart failure | 12,904 (22.6) | 556 (58.7) | 3129 (44.6) | 9219 (18.8) |

| Proportion of patients with an ACSC encounter related to hyperkalemia | 2225 (3.9) | 180 (19.0) | 652 (9.3) | 1393 (2.8) |

| Proportion of patients with an ACSC encounter related to volume overload | 395 (0.7) | 44 (4.7) | 121 (1.7) | 230 (0.5) |

| Proportion of patients with an ACSC encounter related to malignant hypertension | 50 (0.1) | 5 (0.5) | 9 (0.1) | 36 (0.1) |

ACSC, ambulatory care sensitive condition; IQR, interquartile range.

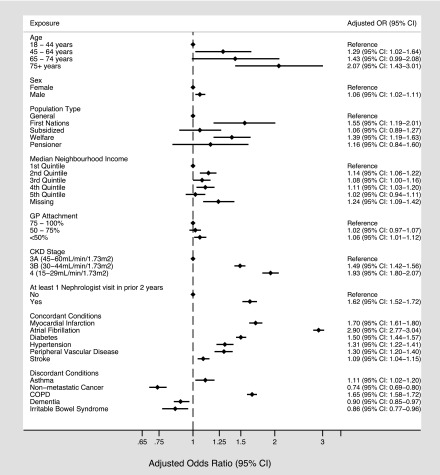

Using multivariable logistic regression, we identified many factors that were independently associated with having at least one ACSC hospitalization, including older age and stage of CKD (Figure 2). Registered First Nations status (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.19 to 2.01), lowest household income quintile (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.22), poor primary care attachment (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.12), prior nephrologist visits (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.52 to 1.72), and a number of comorbid chronic conditions were also associated with having an ACSC hospitalization. The concordant conditions that had the strongest association with the risk of ACSC included myocardial infarction (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.61 to 1.80) and atrial fibrillation (OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 2.77 to 3.04), whereas chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.58 to 1.72) was the discordant condition with the strongest association with ACSC hospitalization among patients with CKD. Sensitivity analyses that were limited to the persistent or episodic high–use groups (separately and one at a time) showed similar findings.

Figure 2.

Clinical and demographic factors associated with having at least one ambulatory care sensitive hospitalization among high users of inpatient services (n=7957). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GP, general practitioner; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

In this large population–based cohort of adults with CKD and at least one hospitalization, we found that 1.7% of patients were persistent high users of hospital services and that 12.3% were episodic high users. Although this subgroup represents a small proportion of the total CKD population (14%), they accounted for 45.5% of all CKD–related hospitalizations and 36.5% of CKD–related hospital days. Furthermore, there are specific clinical and demographic factors associated with greater risk of ACSC hospitalization, suggesting opportunities to reduce inpatient use by focusing on strategies to improve community-based care for subsets of this patient population.

Our results add to those from previous studies. Wiebe et al. (19) found that approximately 10% of hospital encounters may be ambulatory care sensitive among patients with CKD. Our work extends these findings to a hospitalized cohort and explores the influence that patterns of inpatient use have on the proportion of encounters deemed to be potentially preventable. Overall, we found that almost one in four hospitalized patients with CKD will have a CKD–related ACSC encounter, most notably for heart failure or hyperkalemia. Furthermore, large proportions of these events are observed in the small subset of patients who drive health care utilization and subsequent cost (persistent and episodic high users). This may have implications from a case management perspective, such as devising strategies to reduce the risk of heart failure and hyperkalemia in the outpatient setting. More intensive management provided to a high-risk subset of patients could substantially improve patient experience and the cost-effectiveness of care. Given the high 3-year mortality observed in this population (>50% among persistent and episodic high users), targeted strategies may also reduce mortality and improve overall health outcomes—assuming that reductions in CKD–related hospital use could be realized.

Furthermore, we were able to identify clinical and demographic factors associated with hospitalization for a CKD-specific ACSC. Specifically, we found that at-risk populations (including registered First Nations and low income) were associated with higher odds of ACSC hospitalization. This could be related to geographic limitations that may prevent timely access to outpatient care for CKD-specific issues but may also be confounded by other social determinants of health. Regardless, our results suggest that there may be patient groups that could be targeted for more coordinated community care to potentially reduce the risk of CKD hospitalization. Various outpatient interventions have been shown to reduce the risk of rehospitalization and in turn, inpatient costs in the setting of specific chronic conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (36–38). Whether these interventions can be adapted and put in place to reduce ACSC hospitalizations for complex patients with multiple comorbidities (the norm for patients with CKD) remains to be determined and should be a high priority for future research.

Our findings also highlight the importance of continuity of primary care for patients with multiple chronic conditions (39,40). We observed that poor primary care attachment was associated with increased odds of being a high inpatient user and having one or more ACSC hospitalizations. Prior work has shown that hospital costs per patient decrease with better attachment to primary care, particularly for those with diabetes and congestive heart failure (41). Furthermore, greater continuity of care has been associated with decreases in ACSC hospitalization (42,43). Improving attachment to primary care among patients with CKD may, therefore, be an intervention that should be considered for future research in this patient population.

Our study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, the construct of ambulatory care sensitive hospitalization likely represents a spectrum of preventability that requires exploration into other aspects of patient care, including overall frequency and quality of care received in the outpatient setting. Although we were able to adjust for physician attachment (as a potentially important provider–level factor), there are other important patient– and system–level factors that may place patients with CKD at increased risk for hospitalization for CKD-specific events. Second, although we were able to measure a number of clinical and demographic characteristics, we were unable to account for other social determinants of health that may confound the risk of hospitalization for CKD-related events. Third, we classified participants as having CKD on the basis of a single eGFR measurement, which may have resulted in misclassification. Despite these limitations, our study has a number of strengths. We used population-based data from a single Canadian province, which provides a unique opportunity to assess patterns of hospital use and risk of CKD-related hospitalization among a high-risk cohort of patients. We also grounded this work in a recognized framework for the study of health care utilization (the Andersen Health Behavioral Model) (27) and included important patient– and provider–level factors within our analysis.

We found that small numbers of patients with CKD are persistent high users of hospital services and that a large proportion of their encounters is potentially preventable. Although we acknowledge that the construct of ambulatory care sensitive hospitalizations is complex, our findings suggest that there is room to improve care for this high-risk population. Future work is needed to determine if improvements in community-based and primary care could mitigate the number of CKD–related hospital events that occur among the subset of patients who drive health care use and spending. However, this will require a better understanding of the interplay between concurrent morbidity and health care need among patients with CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

B.R.H. is supported by the Roy and Vi Baay Chair in Kidney Research. B.J.M. is supported by the Svare Professorship in Health Economics and a Health Scholar Award by Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (AIHS). M.T.J. is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). P.R. is supported by operating grants from the CIHR. M.T. is supported by the David Freeze Chair in Health Services Research. The Interdisciplinary Chronic Disease Collaboration is funded by the AIHS Collaborative Research and Innovation Opportunity Team Grants Program.

Preliminary results from this manuscript were presented at the American Society of Nephrology Annual Conference in San Diego, California on November 7, 2015.

P.E.R. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This study is, in part, on the basis of data provided by Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services. The interpretation and conclusions are those of the researchers and do not represent the views of the Government of Alberta. Neither the Government of Alberta nor Alberta Health express any opinion in relation to this study.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Are Ambulatory Care–Sensitive Conditions the Fulcrum of Hospitalizations for CKD Patients?,” on pages 1927–1928.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04690416/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Drey N, Roderick P, Mullee M, Rogerson M: A population-based study of the incidence and outcomes of diagnosed chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 677–684, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eknoyan G, Lameire N, Barsoum R, Eckardt KU, Levin A, Levin N, Locatelli F, MacLeod A, Vanholder R, Walker R, Wang H: The burden of kidney disease: Improving global outcomes. Kidney Int 66: 1310–1314, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, James MT, Klarenbach S, Quinn RR, Wiebe N, Tonelli M; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 303: 423–429, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang QL, Rothenbacher D: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in population-based studies: Systematic review. BMC Public Health 8: 117, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumeister SE, Böger CA, Krämer BK, Döring A, Eheberg D, Fischer B, John J, Koenig W, Meisinger C: Effect of chronic kidney disease and comorbid conditions on health care costs: A 10-year observational study in a general population. Am J Nephrol 31: 222–229, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honeycutt AA, Segel JE, Zhuo X, Hoerger TJ, Imai K, Williams D: Medical costs of CKD in the Medicare population. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1478–1483, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent S, Schlackow I, Lozano-Kühne J, Reith C, Emberson J, Haynes R, Gray A, Cass A, Baigent C, Landray MJ, Herrington W, Mihaylova B; SHARP Collaborative Group : What is the impact of chronic kidney disease stage and cardiovascular disease on the annual cost of hospital care in moderate-to-severe kidney disease? BMC Nephrol 16: 65, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DH, Gullion CM, Nichols G, Keith DS, Brown JB: Cost of medical care for chronic kidney disease and comorbidity among enrollees in a large HMO population. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1300–1306, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institute for Health Information : National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2012, Ottawa, ON, Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosella LC, Fitzpatrick T, Wodchis WP, Calzavara A, Manson H, Goel V: High-cost health care users in Ontario, Canada: Demographic, socio-economic, and health status characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res 14: 532, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schore JL, Brown RS, Cheh VA: Case management for high-cost Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev 20: 87–101, 1999 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwenk TL: The patient-centered medical home: One size does not fit all. JAMA 311: 802–803, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wodchis WP, Austin PC, Henry DA: A 3-year study of high-cost users of health care. CMAJ 188: 182–188, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Zhang J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Walsh M, Culleton BF: Association between multidisciplinary care and survival for elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 993–999, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemmelgarn BR, Zhang J, Manns BJ, James MT, Quinn RR, Ravani P, Klarenbach SW, Culleton BF, Krause R, Thorlacius L, Jain AK, Tonelli M; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Nephrology visits and health care resource use before and after reporting estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA 303: 1151–1158, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ronksley PE, Hemmelgarn BR: Optimizing care for patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 133–138, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute for Healthcare Improvement: IHI Triple Aim Initiative, 2015. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed December 12, 2015

- 19.Wiebe N, Klarenbach SW, Allan GM, Manns BJ, Pelletier R, James MT, Bello A, Hemmelgarn BR, Tonelli M; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Potentially preventable hospitalization as a complication of CKD: A cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 230–238, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Guthrie B, James MT, Quan H, Fortin M, Klarenbach SW, Sargious P, Straus S, Lewanczuk R, Ronksley PE, Manns BJ, Hemmelgarn BR: Comorbidity as a driver of adverse outcomes in people with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 88: 859–866, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemmelgarn BR, Clement F, Manns BJ, Klarenbach S, James MT, Ravani P, Pannu N, Ahmed SB, MacRae J, Scott-Douglas N, Jindal K, Quinn R, Culleton BF, Wiebe N, Krause R, Thorlacius L, Tonelli M: Overview of the Alberta Kidney Disease Network. BMC Nephrol 10: 30, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garella S: The costs of dialysis in the USA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12[Suppl 1]: 10–21, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallick NP: The costs of renal services in Britain. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12[Suppl 1]: 25–28, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berk ML, Monheit AC: The concentration of health care expenditures, revisited. Health Aff (Millwood) 20: 9–18, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joynt KE, Gawande AA, Orav EJ, Jha AK: Contribution of preventable acute care spending to total spending for high-cost Medicare patients. JAMA 309: 2572–2578, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 36: 1–10, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Fortin M, Guthrie B, Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Klarenbach SW, Lewanczuk R, Manns BJ, Ronksley P, Sargious P, Straus S, Quan H; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Methods for identifying 30 chronic conditions: Application to administrative data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 15: 31, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piette JD, Kerr EA: The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care 29: 725–731, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaakkimainen RL, Klein-Geltink J, Guttmann A, Barnsley J, Jagorski B, Kopp A: Indicators of Primary Care Based on Administrative Data, Toronto, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jee SH, Cabana MD: Indices for continuity of care: A systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 63: 158–188, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Billings J, Anderson GM, Newman LS: Recent findings on preventable hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 15: 239–249, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Billings J, Zeitel L, Lukomnik J, Carey TS, Blank AE, Newman L: Impact of socioeconomic status on hospital use in New York City. Health Aff (Millwood) 12: 162–173, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanmartin CKS, the LHAD Research Team: Hospitalizations for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSC): The Factors That Matter, Ottawa, ON, Canada, Statistics Canada, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao S, Manns BJ, Culleton BF, Tonelli M, Quan H, Crowshoe L, Ghali WA, Svenson LW, Ahmed S, Hemmelgarn BR; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Access to health care among status Aboriginal people with chronic kidney disease. CMAJ 179: 1007–1012, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, Rouleau M, Beaupré A, Bégin R, Renzi P, Nault D, Borycki E, Schwartzman K, Singh R, Collet JP; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease axis of the Respiratory Network Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec : Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med 163: 585–591, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moullec G, Lavoie KL, Rabhi K, Julien M, Favreau H, Labrecque M: Effect of an integrated care programme on re-hospitalization of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 17: 707–714, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rice KL, Dewan N, Bloomfield HE, Grill J, Schult TM, Nelson DB, Kumari S, Thomas M, Geist LJ, Beaner C, Caldwell M, Niewoehner DE: Disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182: 890–896, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glazier RH, Moineddin R, Agha MM, Zagorski B, Hall R, Manuel DG, Sibley LM, Kopp A: The Impact of Not Having a Primary Care Physician among People with Chronic Condtions, Toronto, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R: Continuity of care: A multidisciplinary review. BMJ 327: 1219–1221, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollander MJ, Kadlec H, Hamdi R, Tessaro A: Increasing value for money in the Canadian healthcare system: New findings on the contribution of primary care services. Healthc Q 12: 32–44, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canadian Institute for Health Information : Continuity of Care with Family Medicine Physicians: Why It Matters, Ottawa, ON, Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menec VH, Sirski M, Attawar D, Katz A: Does continuity of care with a family physician reduce hospitalizations among older adults? J Health Serv Res Policy 11: 196–201, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.