Summary

We evaluate function outcomes of the reverse-flow ALT perforator flap to reconstruct severe post-burn knee contracture. Between October 2012 and December 2014, 10 patients with severe post-burn knee contracture were subjected to reconstruction with 10 ipsilateral reversed-flow ALT perforator flaps. All the patients were male. Ages ranged from 15 to 47 years (mean = 32 years). Time from burn injury to patient presentation ranged from 2-8 months. All patients demonstrated post-burn flexion contracture of the knee joint, ranging from 35 to 75 degrees. Flap sizes ranged from 8×16 to 12×26 cm. The flaps and skin grafts were carried out without major complications. Only minor complications occurred, such as transient, mild congestion immediately after inset in two flaps. Two flaps developed superficial necrosis at the distal edge. One case sustained partial skin graft loss due to haematoma. One case complained of skin hyperpigmentation and hypertrophic scars around the graft. Secondary debulking procedures were required in two cases. The entire donor sites were closed by partial thickness skin graft with acceptable appearance, except one case that was closed primarily. Eight out of ten patients (80%) demonstrated gradual improvement in range of knee motion after a specialized rehabilitation program. Two patients (20%) did not get back full range of motion. RALT perforator flap is the cornerstone for the reconstruction of soft-tissue defects around the knee with acceptable aesthetic and functional results provided that the following items are fulfilled: inclusion of muscle cuff around the pedicle, the pivot point, prevention of pedicle compression after transfer and early surgical intervention on the post-burn knee contracture.

Keywords: post-burn knee contracture, reverse flow ALT flap

Abstract

Nous avons évalué les résultats fonctionnels après utilisation du lambeau perforant antérolatéral de cuisse à flux rétrograde dans la reconstruction des rétractions importantes du genou après brûlure. Entre octobre 2012 et décembre 2014, 10 patients présentant ces rétractions ont subi une reconstruction avec ce type de lambeau perforant. Tous ces patients étaient de sexe male, les âges s’étalaient de 15 à 45 ans (moyenne 32 ans). Le moment chirurgical par rapport la brûlure se situait entre 2 à 8 mois. Tous les patients présentaient une rétraction en flexion du genou entre 35 et 75 degrés. La dimension des lambeaux était de 8 x 16 jusqu’à 12 x 26. Les lambeaux et les greffes cutanées se déroulèrent sans complication majeure. Seule une complication légère et transitoire a été observée avec une congestion de moyenne importance après mise en place du lambeau. 2 lambeaux développèrent une nécrose superficielle au niveau d’une berge distale. I cas présentât une nécrose partielle de la greffe cutanée en rapport avec un hématome. 1 autre cas développa une hyper pigmentation et une hypertrophie cicatricielle autour de la greffe. Un dégraissage secondaire fut nécessaire dans 2 cas. La totalité des sites donneurs fut couverte par des greffes de peau demie épaisse avec un aspect acceptable sauf dans 1 cas de fermeture primaire. 80% des patients présentèrent une amélioration de la mobilité du genou après une réadaptation spécialisée. 2 patients (20%) n’ont pas récupérer complètement leur mobilité. Le lambeau perforant antérolatéral de cuisse à flux inversé est le lambeau de choix pour la reconstruction des pertes de substance du genou avec des résultats esthétiques et fonctionnels acceptables dans la mesure où l’on respecte certaines règles: confection d’un manchon musculaire autour du pédicule, recherche du point pivot, prévention d’une compression du pédicule après transfert et enfin précocité du geste chirurgical après la brûlure.

Introduction

Reconstruction of post-burn contracture scar of the knee is a challenging problem.1 Surgical release of post-burn knee contracture results in large soft tissue defect, exposing important structures in the popliteal fossa that require soft-tissue coverage. The aim of soft-tissue reconstruction around the knee joint is to restore function and an aesthetically-acceptable appearance. Well-vascularised tissue is necessary to ensure the wound heals.2 Different solutions have been described in the literature, such as local cutaneous flaps, fasciocutaneousflaps, muscle flaps3-7 or free flaps. 8,10 The goal of the reconstruction plan is to find the simplest technique likely to achieve wound closure with minimal donor-site morbidity.11-13

In 1984, Song et al.14 first reported the anterolateral thigh flap as a septocutaneous perforator-based flap. It has gained great popularity, especially in mainland China, Japan and Taiwan.15,17

If a soft-tissue defect around the knee requires flap coverage, reverse-flow anterolateral thigh (RALT) perforator flap can be a reliable, effective and durable option. This was first introduced in four cases by Zhang.18

In our current study, we evaluate function outcomes after the use of reverse-flow ALT perforator flap to reconstruct severe post-burn knee contracture.

Patients and methods

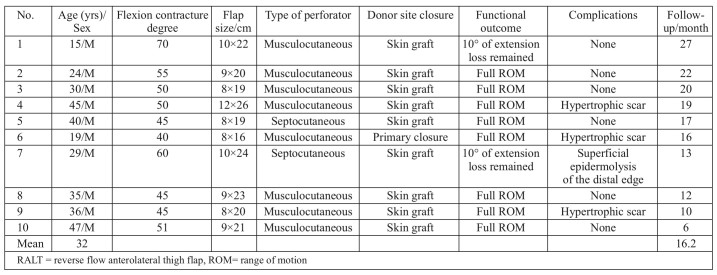

Between October 2012 and December 2014, 10 patients with severe post-burn knee contracture were subjected to reconstruction with 10 ipsilateral distally based ALT perforator flaps. All the patients were male. Ages ranged from 15 to 47 years (mean = 32 years). Time from burn injury to patient presentation at our clinic ranged from 2-8 months. All of the patients demonstrated post-burn flexion contracture of the knee joint, ranging from 35 to 75 degrees. Flap sizes ranged from 8×16 to 12×26 cm (Table I).

Table I. Summary of patients’ data and follow-up period.

There were absolute and relative exclusion criteria. The absolute criteria included: patient not fit for surgery, burnt donor sites and stiff knee joint. The relative criteria included smokers, who had to stop smoking at least one month before the procedure. All the operations were performed under spinal anesthesia except for one patient who had general anesthesia

Operative technique

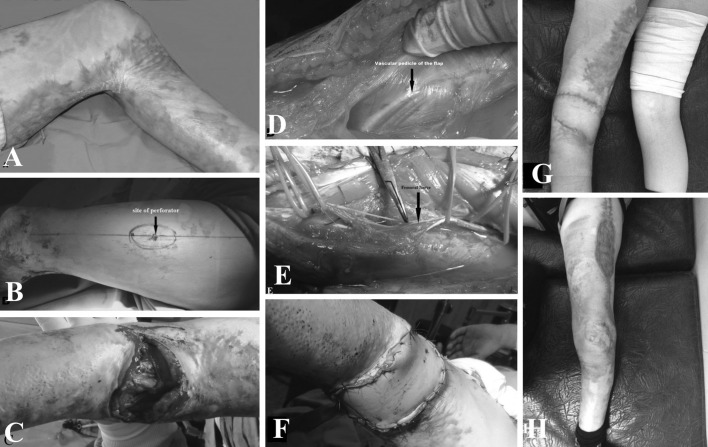

A straight line was marked between the anterior superior iliac spine and the lateral edge of the patella on the ipsilateral side. The midpoint of this line was identified and a 3 cm radius circle was outlined. The perforators that are usually located within this circle were detected by a handheld portable Doppler. The desired size of the flap was marked and centered over the perforators (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. (A) 15-year-old male patient presented with post-burn contracture, left knee, for 6 months. (B) Preoperative marking of the flap. (C) Resultant defect after release of the contracture. (D) Exposure of the vascular pedicle of the flap indicated by arrow. (E) Dissection of the femoral nerve. (F) Reconstruction completed after inset of the flap. (G) One month post-operative result (H) with the donor site closed with partial thickness skin graft.

We began by releasing the post-burn knee contracture by surgical scarotomy, debridement of the fibrous tissues as much as possible, haemostasis and evaluation of the size of the defect to determine the size of the flap. After releasing the contracture a subsequent tendon exposure occurred. We then dissected the flap through the lazy-S incision over the medial margin of the flap, down to the subfascial plane, proceeding with dissection laterally in the subfascial plane to detect perforators passing within either muscle or septum. Searching about the significant perforator, the lateral margin of the flap was determined according to the site of the perforator, if needed. The descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA) was dissected proximally up to the profunda femoral artery (to its origin) to determine the type of perforator. According to the origin of the perforator, if it arose from the descending branch of the LCFA (type I and III) pedicles, the pedicle was divided proximally just after the bifurcation points. If it originated from the transverse branch of the LCFA, called type II and IV pedicles, dissection was more difficult than for types I and III. In the current study, the perforator arose from the transverse branch of the LCFA in one patient only. In this situation, the flap was raised after dividing the lateral circumflex femoral vessel proximal to the bifurcation of the transverse and descending branches, also trying to preserve the venae comitantes as much as possible. Then the lateral margin of the flap was completed to determine the final dimensions of the flap to be elevated. We preferred to leave a cuff of muscle around the perforators. We also preferred to preserve more than two perforators to the flap. Dissection of the DLCF branch was continued distally down to the pivot point, which was determined during the flap design. Before dividing the pedicle, we usually assessed retrograde flow into the flap by clamping the pedicle proximally. If there was a good retrograde flow into the flap, the pedicle was ligated and divided proximally just after the bifurcation points (type I and III pedicles) and before the bifurcation points (type II and IV pedicles). A skin incision was made between the distal end of the flap and the defect, then skin flaps were bilaterally elevated in the subcutaneous plane. The elevated flap was transposed to the defect through this dissected area, and the pedicles were covered with elevated skin flaps and split-thickness skin grafts. The donor site was closed with a split-thickness skin graft or, in one patient, primarily (8 cm or less). Drains were placed beneath the flaps and the donor sites.

In the postoperative period, the patients continued to receive IV 3rd generation cephalosporin for 7-10 days. The flap was checked for viability after 24 hours. The drain was removed after 48 hours. The knees were splinted in an extended position for 1 week after surgery.

The patients were discharged 10 to 14 days after surgery, after the skin graft had started to heal well, and they were followed-up at regular intervals.

Physiotherapy

Returning the patient to the pre-injury function level was of utmost importance. 10-14 days after surgery, a specialized program of physiotherapy was started. It consisted of passive and active range of motion (ROM) exercises for the knee, strengthening exercises for all muscle groups around the knee, and proprioception enhancement. Our aim was for the patient to regain normal ROM and power comparable to the other side, and return to the pre-injury function level.

Functional reconstruction was assessed using the Goniometer to measure both the passive and active range of motion (ROM) of the ankle after one month of physiotherapy.

Results

Ten adult male patients were included in the study. Ten defects were created after surgical release of post-burn contracture scar of the knee joint. The flaps and skin grafts were carried out without major complications. Only minor complications occurred, such as transient, mild congestion immediately after inset in two flaps, which resolved within a few days with no adverse sequelae on flap survival. Two flaps developed superficial necrosis at the distal edge and were treated with debridement and skin graft. One case sustained partial skin graft loss due to haematoma: the wound gradually healed after daily dressing. One case complained of skin hyperpigmentation and hypertrophic scars around the graft. Secondary debulking operations were required in two cases.

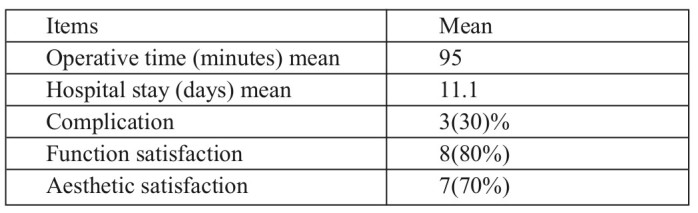

The entire donor sites were closed with partial thickness skin graft with acceptable appearance, except for one case that was closed primarily. No remarkable donor site seromaor haematoma was observed except in one case. Blood supply to the flaps was provided by musculocutaneous perforators in eight cases; in the other two cases septocutaneous perforator was observed coursing in the space between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis muscles. Two to four perforators were identified during flap elevation in all cases. Surgery time ranged from 80 to 120 minutes (mean = 95 minutes). Length of hospital stay ranged from 10- 14 days (mean = 11.1 days) (Table II). The follow-up period ranged from 6 to 27 months (mean = 16.2 months).

As regards function outcome, eight of the ten patients demonstrated a gradual improvement in range of knee motion after a specialized program of rehabilitation that was initiated 10-14 days after surgery. Two patients did not regain full range of motion. However the range of motion they achieved was good enough not to disturb their usual motions.

Discussion

Improper treatment of deep burn wounds around the knee joints inevitably results in post-burn contractures. When they occur, they should be released to restore full functional ability of the lower extremity.19 The aim of knee contracture release is to restore the function and aesthetic contour of the knee joint.20 Different modalities have been used to treat post-burn knee contracture. They include nonsurgical procedures such as splinting. External fixation systems have also been used. 21,22 However, these nonsurgical procedures are not efficient in chronic contractures, and are used mainly for prevention of contracture.

Various surgical procedures have been used for reconstruction, such as local flaps, regional and free flaps. Local cutaneous flaps, such as rotation flaps or advancement flaps, can be used for only small defects around the knee.11,12 Local fasciocutaneous flaps, such as the lateral sural cutaneous artery island flap, the saphenous flap, and the lateral or medial genicular artery island flap are usually associated with sacrificed perforator or sensory disturbance around the knee joint.

Local flaps have no role when extensive soft-tissue defects are present.23 Most muscle flaps such as lateral or medial gastrocnemius, 5 soleus, sartorius,24 vastus medialis25 and distally based vastus lateralis26 are too bulky to cover soft tissue defects around the knee and usually lead to aesthetic and functional deficits. Free flaps can be used to cover knee defects when local flaps are unavailable or the knee soft tissue defect is extensive, but the deep-sited recipient vessels at this level make the vascular anastomosis of free flaps more difficult, postoperative care also.2,11-12

Gravvanis et al. reported that perforator flaps have been a true revolution in soft tissue reconstruction around the knee: they can also replace “like with like” with minimal donor-site morbidity. They also presented the successful use of distally based ALT flap with a venous supercharge to reconstruct tibial tuberosity. They recommended the venous supercharge to this flap as a routine procedure because it can eliminate any vascular problems.2

The RALT perforator flap is characterized by:

long vascular pedicle;

very large skin territory;

possible combination with fascia lata for patellar tendon reconstruction (in the event of patellar tendon loss);

donor-site scar can be easily hidden with minimal morbidity;

moderate thickness;

no scarification of a major artery or muscle;

it allows early mobilization; patients can return to their normal daily activities in a short time

Zhang was the first to describe the reversed anterolateral thigh island flap, and reported that the flap is reliable based on the anastomosis of the lateral superior genicular artery with descending branch of LCFA in a retrograde manner.18

Pan et al. have clearly defined the retrograde vascular pedicle. According to their research, the descending branch always anatomised with the lateral superior genicular artery or the profunda femoral artery or both.11 They also mentioned that the mean retrograde perfusion pressures in RALT flaps are adequate for flap survival. As regards venous drainage, the flap drained through the venae comitantes along the sides of the arteries.11

According to Shieh et al.,27 type of perforator is important in deciding on the flap. Fortunately, in the current study all the perforators originated from the descending branch of the LCFA (type I or type III), except in one patient where the perforator originated from the transverse branch of LCFA (type II). In this situation, the lateral circumflex femoral vessel proximal to the bifurcation of the transverse and descending branches was ligated, also trying to preserve the venae comitantes as much as possible.

We agree with Demirseren et al.28 that pivot point location is an important step in flap elevation. The pivot point of the RALT flap can be determined at 3-10 cm proximal to the lateral superior angle of the patella. They also mentioned that the terminal part of the descending branch can be dissected carefully up to 10 cm above the knee.11 If a longer pedicle is needed, the pivot point can be shifted distally up to 3 cm above the knee. In the current study, eight patients (80%) had musculocutaneous perforators and only two had a septocutaneous perforator (20%). Also in the current study, RALT perforator flaps with pedicles of about 26 cm were safely transferred, but the others needed to dissect up to 3 cm above the knee. Transient, mild congestion immediately after inset was seen in two cases, which resolved within a few days with no adverse sequelae on flap survival. This coincides with the explanation of Wong and Tan. They postulated that mechanisms that enable reverse flow include ‘‘crossover’’ flow via bypass channels connecting the paired venae comitantes.29

Gravvanis et al. compared the option of distally based ALT flap vs. gastrocnemius flap, and concluded that ALT is less bulky than the gastrocnemius, has a long arc of rotation to reach above and below the knee defect, and provides large skin territory to resurface the whole knee.30

Gravvanis et al. mentioned that there is much controversy in the literature regarding the optimal management of skin necrosis around the knee. Muscle flap remains the standard to which all other flaps should be compared. Perforator flaps have been a true revolution in soft tissue reconstruction around the knee, with particular advantages due to their low donor morbidity and long pedicles. In the case of a free flap, the choice of recipient vessels is the key point to the reconstruction. With meticulous preoperative planning, by identifying the reconstruction needs and by understanding the reconstructive algorithm, the surgeon should be able to manage a knee defect with a high success rate.31

Operative times in our cases varied between 80 and 120 minutes; these times are no longer than the operative times for the other free flap approaches that are used to treat knee defects. Also, the operative times decrease with increasing experience (Table II).

Table II. Outcome data.

The donor site was closed primarily in one patient (the flap width was no more than 8 cm); in all the other patients, the donor site was large and was closed with partial thickness skin graft. Fortunately, all of the patients in our series were male and they did not complain about the donor-site scar because they could be easily hidden. We used debulking procedures in two cases. We tried to plane the flap in the lower two-thirds of the thigh (subcutaneous fat is thinner in the lower two-thirds than in the upper half of the thigh) to avoid excess bulk.

The release of contractures results in large soft tissue defects at the knee, so the size of the flap is another important factor. Fortunately, the ALT flap provides a very large skin territory. We used very large flaps based on only one perforator. The largest flap in our series was 26×10 cm.

The knee was splinted in the extended position for only 1 week in the postoperative period. During the follow up period, there was no recurrence of contracture in any of the patients.

As regards function outcomes, all the patients in the current study demonstrated a gradual improvement in range of knee motion after a postoperative specialized program of physiotherapy. Two patients (20%) did not regain full range of motion. In those cases, the achieved range of motion was good enough not to disturb the patients’ usual motions. Also, time from injury to patient presentation at our clinic was no more than 6 months (Table II). In my opinion, in the case of longstanding contracture of joints, there is more than one tissue affected, such as bone, capsule, muscle, tendons, ligaments, vessels and nerves. Thus, it is not always possible to release contracture to the full extent, so function outcomes in these circumstances are not encouraging. So prevention is better than cure: the knee needs to be splinted in the extended position during the healing period to prevent flexion contractures. Splints are required for 2 to 6 months, especially at night, to prevent recurrences.

Besides the critical points, such as planning of the pivot point, inclusion of muscle cuff around the pedicle and prevention of pedicle compression after transfer, also the timing of surgical intervention on the post-burn knee contracture is a very important factor for achieving good aesthetic and function outcome. The RALT perforator flap is an excellent choice, both functionally and aesthetically, for the reconstruction of softtissue defects around the knee joint.

Conclusion

The RALT perforator flap is the cornerstone for the reconstruction of soft-tissue defects around the knee with acceptable aesthetic and functional results, provided that the following items are fulfilled: preservation of muscle cuff around the pedicle, the pivot point, avoidance of pedicle compression after flap inset and early surgical intervention on the post-burn knee contracture (no more than 6 months after occurrence of the contracture).

References

- 1.Nahabedian MY, Mont MA, Orlando JC, Delanois RE, Hungerford DS. Operative management and outcome of complex wounds following total knee arthroplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1688–1697. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gravvanis A, Britto JA. Venous augmentation of distally based pedicled ALT flap to reconstruct the tibial tuberosity in a severely injured leg. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;62:290–292. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31817d81fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold PG, Prunes-Carrillo F. Vastusmedialis muscle flap for functional closure of the exposed knee joint. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:69–69. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198107000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moscona AR, Keret D, Reis ND. The gastrocnemius muscle flap in the correction of severe flexion contracture of the knee. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1982;100:139–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00462353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdri NA, Darzi MA. Z-lengthening and gastrocnemius muscle flap in the management of severe postburn flexion contractures of the knee. J Trauma. 1998;45:127–127. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mani MM, Chatre M. Reconstruction of the burned lower extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 19;19:693–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajajic N, Gang RK, Darweesh M, Abdul Fetah N, Kojic S. Reconstruction of soft tissue defects around the knee with the use of the lateral suralfasciocutaneous artery island flap. Eur J Plast Surg. 1999;22:12–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson PE, Harris GD, Nagle DJ, Lewis VL. The sural artery and vein as recipient vessels in free flap reconstruction about the knee. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1987;3:233–233. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuen JC, Zhou AT. Free flap coverage for knee salvage. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37:158–158. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park S, Eom JS. Selection of the recipient vessel in the free flap around the knee: the superior medial genicular vessels and the descending genicular vessels. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1177–1177. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200104150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan SC, Yu JC, Shieh SJ, Lee JW. Distally based anterolateral thigh flap: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1768–1775. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000142416.91524.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CY, Hsieh CH, Kuo YR, Jeng SF. An anterolateral thigh perforator flap from the ipsilateral thigh for soft-tissue reconstruction around the knee. Plast Reconstr Surg (RVALT) 2007;120:470–473. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000267432.03348.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy V, Stevenson TR. Lower extremity reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000305928.98611.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song, YG, Chen GZ, Song YL. The free thigh flap: A new free flap concept based on the septocutaneous artery. Br J Plast Surg. 1984;37:149–149. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(84)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demirkan F, Chen HC, Wei FC. The versatile anterolateral thigh flap: amusculocutaneous flap in disguise in head and neck reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:30–30. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei FC, Çelik N, Chen HC. Combined anterolateral thigh flap and vascularized fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap in reconstruction of extensive composite mandibular defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:45–45. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu P, Sanger JR, Matloub HS. Anterolateral thigh fasciocutaneous island flaps in perineoscrotal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:610–610. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200202000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang G. Reversed anterolateral thigh island flap and myocutaneous flap transplantation. Zhonghua Yi XueZaZhi. 1990;70:676–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraemer MD, Jones T, Deitch EA. Burn contractures: incidence, predisposing factors, and results of surgical therapy. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998;9:261–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallock GG. GG: Local knee random fasciocutaneous flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;23:289–296. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198910000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett GB, Helm P, Purdue GF, Hunt JL. Serial casting: a method for treating burn contractures. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1989;10:543–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan RB, Daher J, Wasil K. Splints and scar management for acute and reconstructive burn care. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27:71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu TY, Jeng SF, Yang JC, Shih HS. Reconstruction of the skin defect of the knee using a reverse anterolateral thigh island flap: cases report. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:198–201. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31819bd6f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petty CT, Hogue RJ Jr. Closure of an exposed knee joint by use of a sartorius muscle flap: Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;62:458–458. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197809000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold PG, Prunes-Carrillo F. Vastusmedialis muscle flap for functional closure of the exposed knee joint. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:69–69. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198107000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swartz WM, Ramasastry SS, McGill Jr. Distally based vastuslateralis muscle flap for coverage of wounds about the knee. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:255–255. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198708000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shieh SJ, Chiu HY, Yu JC, Pan SC. Free anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of head and neck defects following cancer ablation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2349–2357. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demirseren ME, Efendioglu KC, Demiral O. Clinical experience with a reverse-flow anterolateral thigh perforator flap for the reconstruction of soft-tissue defects of the knee and proximal lower leg. J of Plast Reconstr & Aesth Surg. 2011;64:1613–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong CH, Tan BK. Maximizing the reliability and safety of the distally based sural artery flap. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2008;24:589–594. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1090604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gravvanis A, Iconomou TG, Panayotou PN, Tsoutsos DA. Medial Gastrocnemius muscle flap versus distally based anterolateral thigh flap: conservative or modern approach to exposed knee joint? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:932–932. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000180888.41899.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gravvanis A, Kyriakopoulos A, Kateros K, Tsoutsos D. Flap reconstruction of the knee: A review of current concepts and a proposed algorithm. World J Orthop. 2014;18:603–613. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i5.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]