Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe the changing characteristics and comorbidity levels of first-time entrants into the BC Methadone Program from 1998–2006.

METHODS

The study included all first-time entrants in the BC Methadone program from 1998 to 2006, as identified through provincial administrative drug dispensation data. Generalized linear regression models were used to determine whether the level of comorbidity of new treatment entrants, measured by the hospitalization-based Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and drug dispensation-based Chronic Disease Score (CDS), changed over time, controlling for other covariates.

RESULTS

A total of 12,238 individuals initiated MMT during the study period. The number of first-time entrants into MMT rose sharply from 1998 to 2000, and after a three year period of decline from 2000–2003, stabilized from 2003 to 2006. The age of first-time entrants, as well as the proportion of females and clients from rural regions increased over the study period. The odds of first-time treatment entrants having a nonzero and moderate (CCI<=4) Charlson score(CCI) was increased by 9% annually; and mean CDS increased by 21.95(95% CI= [12.96, 30.94]) on the CDS-II scale per year throughout the study period, after adjusting for age, sex and neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status. At the same time, the odds of having a patient with high (CCI>=5) CCI decreased by 13 % annually, which was almost entirely due to the significant decrease in proportion of first-time entrants with HIV/AIDS and severe liver diseases including hepatitis C and B.

CONCLUSION

First-time entrants into the BC Methadone program presented with progressively higher level of medical comorbidity (except for HIV and sever liver disease) over the study period. As these individuals are often unable to navigate the healthcare system well enough to receive adequate primary care, we believe MMT represents a key opportunity to provide medical care and social support for patients with comorbid conditions.

Keywords: Methadone Maintenance Treatment, Opioid dependence, substance abuse treatment, Charlson Comorbidity index, Chronic Disease Score

Introduction

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), a treatment philosophy emphasizing indefinite maintenance for opioid dependence, is widely accepted as an effective form of treatment across a variety of study designs and cultural and ethnic groups (1). Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of methadone maintenance in decreasing illicit opiate use (2), risk of overdose death (3; 4), infectious-disease transmission(5), criminal activity (6) and enhancing social productivity of clients (4; 7).

Coexisting chronic diseases are a contributing factor to premature death among opioid users (3; 8). This population is at elevated risk of hepatitis (viral hepatitis (B,C and D), cirrhosis, lymphocytic infiltrate) (9; 10), HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis(2; 5), cardiac complications(coronary artery disease, endocarditis, myocardial infarction) (6; 9), renal complications (kidney failure, renal amyloidoisis ) (7), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8; 9), hypertension (9,3), diabetes mellitus (8; 11), low bone density that results in nonspecific musculoskeletal pain (12) and low vitamin D status that leads to a higher risk of fracture by exacerbating osteoporosis (13). In addition to chronic medical comorbidities, MMT patients have a high prevalence of mental health disorders, including major depression, anxiety disorders and personality disorders (14).

The number of clients accessing MMT has increased in British Columbia (BC) and elsewhere in Canada, following administrative transfer from the federal government to provincial colleges of physicians and surgeons in 1996 (15). MMT was subsequently de-regulated with relaxed constraints on physicians wishing to deliver treatment and the introduction of community-based treatment (i.e. office-based prescription and dispensation in community-based pharmacies (16). New guidelines liberalized methadone authorization procedures for physicians and resulted in increased number of active physicians prescribing methadone (17). From 1996 to 2006, the number of active prescribing physicians in BC grew from 238 to 327 and the number of dispensing community-based pharmacies increased from 131 to 482 (18).

As the MMT program has expanded across Canada, it is of interest to policy makers to determine whether the patient population presenting for treatment has changed over time. Studying change in patient population is often used as a means of planning purpose such as assessing the necessity for implementing comprehensive care (19, 20). Strike et al. (19) discussed that following the revision of treatment guidelines in Ontario, the age distribution of patients shifted toward younger patients (age 20–29) while distribution of clients by sex were stable (70% male) from 1996–2001. Brands et al. (20) found that with rapid expansion of the MMT program in Ontario from 1994 to 1998, there was a broadening of patient profiles toward more “stable” clients as the prevalence of HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C and serious psychiatric problems decreased among first-time entrants. It is unclear whether these findings are consistent across Canada given the potential for differentials level of treatment accessibility and distinct treatment settings across Canada prior to de-regulation (15).

Although many clients presenting for MMT suffer from coexisting chronic diseases, most programs in methadone clinics and office-based environments in Canada provide minimal onsite medical services, other than regular urine drug screening tests (2; 10; 22). Even though in 2009 the formal guidelines of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia (17) added testing for hepatitis C, serum transaminase levels and a relevant physical exam during the initial assessment, medical care across MMT programs varies considerably in BC (18). In practice, MMT patients rarely receive proper diagnosis and management of their medical comorbidities. Higher levels of medical comorbidity among first-time MMT entrants over the study period would indicate a growing need to better integrate MMT with primary care (2; 9). The objectives of this study were to evaluate the changes in characteristics and comorbidity status of first-time MMT entrants and to provide insight into their relevance to utilization of MMT during 1998–2006.

Materials and Methods

Data sources

Data sources for this study were the British Columbia PharmaNet database (23) and the Hospital separations database, both components of Population data BC (24). The PharmaNet database records all prescription drug dispensations in British Columbia as well as data on age, sex, date of entrance into MMT program and socioeconomic status aggregated by Local Health Area (LHA). The study cohort featured linked data on hospital separations, which included indication of most responsible diagnosis by ICD9/ICD10 codes. The study was approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

Study population

All first-time MMT entrants from January 1st, 1998–April 1st, 2006, defined within the PharmaNet database, were included in the study. First-time entrants were defined as not having any record of prior methadone treatment for opioid dependence for at least 2 years. While PharmaNet data was available for the period January 1st, 1996 – December 31st 2006, we only considered individuals initiating after January 1st 1998, in order to comply with study entry criteria. We considered treatment episodes up to April 1st, 2006 as we did not have access to hospitalization records beyond this point.

Outcome definition and measures

Comorbidity scores combine comorbid conditions identified in hospitalization or drug dispensation records into a single index score, weighted for disease severity (25). These scores are used often in literature as baseline controls for confounding in observational studies using administrative data (25–27). They have been also used to delineate trends of disease severity for a cohort of patients over time (28).

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) is constructed from a set of 17 conditions1 indicated in hospitalization-based ICD9/10 discharge diagnosis records; each condition is assigned a weight, with higher weights indicating greater severity (25; 26). An individual’s CCI score at a point in time (using data from the prior 12 months, for instance) is the sum of these weights. The CCI used in this study is based on Deyo et al. (26), and has been shown to be predictive of in-hospital and post-operative mortality. It has also been validated against range of measures that reflect resource use, including length of stay and re-admission (27). The Chronic Disease Score (CDS) is a risk-adjustment metric based on age, gender, and history of dispensed drugs. Chronic Disease Score (CDS) has been calculated from dispensed drugs data six months prior to entry based on Clark’s CDS-II definition. The CDS-II was originally designed to predict one-year costs and one-year primary care visits by Clark et al. (25). It captures information regarding several diseases through dispensed drug data including both physical and mental health conditions (25). A SAS Macro program calculating CDS for patients at the time of treatment entry was modified to accommodate the Canadian Drug Product Database (DPD) coding system (33). SAS v9.2 has been used to generate CCI scores from hospitalization data from (33) and other analyses in this study.

We have included both CDS and Charlson index in our analysis since each reflect a distinct dimension for MMT patient’s comorbidity status. The CCI reflects medical comorbidity level based on diseases which are severe enough to require hospitalization. CDS, on the other hand, is based on prescription drugs and reflects treated comorbidity.

Low neighbourhood socioeconomic status has been shown to be associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes among MMT patients (30). To capture neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status (SES), geographical data was matched with 2001 census data(29) on income (incidence of low income defined as annual income of less than $30,000), employment rate (labour force participation rate of adults) and education (incidence of low education defined as percentage of 18 year olds without high school diplomas) and health (life expectancy at birth). Categorical variables were defined for each SES variable based on the 2001 BC census median (29) of each variable in univariate analysis. Local health areas were considered urban if they included an urban centre with a population > 50,000, and rural otherwise (29).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for patient characteristics were presented over three periods, defined based on the annual frequency of first-time entrants into treatment. Univariate inference of differences across cohorts of first-time entrants in these periods was executed using Chi-square and Kruskal-Walls tests for binary and ordinal variables, respectively.

The objective of the multivariate analysis was to determine whether a time trend, independent of other relevant covariates, was evident in the chosen measures of comorbidity. A statistically significant and positive coefficient on the time trend variable indicates there is an increasing trend in the comorbidity level of first-time MMT entrants during the study period, independent of any change in patient demographics. A Generalized linear model, with identity link and gamma distribution, was used to estimate the effect of the selected covariates on the CDS scores of first-time treatment entrants. Given the high frequency of zero CCI scores throughout follow-up, a multinomial cumulative logistic model was used and the response variable was divided into three categories: (1) CCI=0, (2) 1≤CCI ≤4, (3) CCI ≥5; this categorization was based on the distribution of observed CCI scores in the study population.

Results

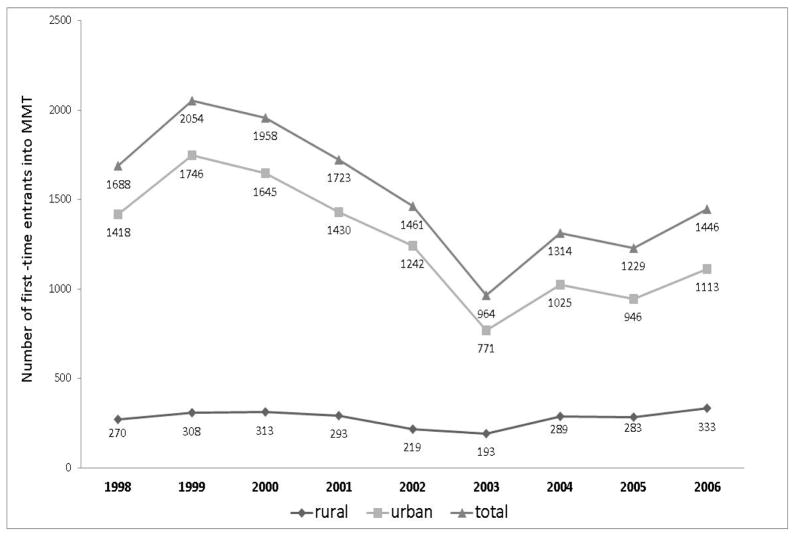

A total of 12,615 first-time MMT entrants were identified during the study period. Figure 1 shows the number of first-time entrants at each year during this period. The study follow-up is divided into three periods. The number of first-time entrants increased from January 01, 1998 to March 31, 2000, then decreased from April 01, 2000 to March 31, 2003, and stabilized to about 1200 to 1450 first-time entrants per calendar year from April 01, 2003–March 01, 2006.

Figure 1.

Number of first-time entrants from urban* and rural local health areas to Methadone Treatment plotted annually from 1998–2006** in British Columbia, Canada.

* Urban is defined as a Local Health Area containing a city with more than 50,000 residents; **Although our study period ends at middle of the 2006 (01 April 2006) due to lack of hospitalization data for the rest of 2006, the number of new entrants is shown for the full year based on Pharmanet data(20)

Table 1 describes the patient characteristics across three time periods over the study follow-up. Due to missing data mostly for comorbidity scores and SES variables, total of 12,238 were used in the analyses. While the mean age and percentage of female clients among first-time entrants increased from the first period to the third (2.5 year increase in mean age and 1% increase of female clients, both p-value<0.01), the percentage of new clients from urban areas decreased by 6% (p-value<0.01). Neighbourhood level socioeconomic status of first-time entrants showed a significant change in several aspects (all p-value<0.01, except for education SES variable). Comparing the first period to the third, one can see an increase in the share of lower education and lower life expectancy neighbourhoods in the cohort of first-time entrants by 3% and 6% respectively. Lower income and lower employment neighbourhoods increased their share in the cohort of first-time entrants by 2% from first to second period while they decreased from second to the third period. If studied annually, the share of all lower SES neighbourhoods in the cohort of first-time entrants shows an overall increasing trend, with some oscillations (annual proportion figures for SES variables not shown).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of new entrants in Methadone Treatment (n =12238), British Columbia, Canada (98-06)

| April 1, 1998–March 31, 2000 (n*=3872) |

April 1, 2000–March 31, 2003 (n=4758) |

April 1, 2003–March 31, 2006 (n=3608) |

p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age† [Mean (SD) ] | 34.2 (10) | 34.6 (11) | 36.7(12) | p<0.001 |

| Female [ N(%) ] | 1278 (33) | 1523 (32) | 1227 (34) | p =0.006 |

| Urbancity†† [ N(%) ] | 3252(84) | 3949(83) | 2814(78) | p <0.001 |

| SES††† [ N(%) ] | ||||

| Low Income‡ | 2091(54) | 2664(56) | 1840(51) | |

| High Income | 1781(46) | 2094(44) | 1768(49) | p <0.001 |

| Low education | 2091(54) | 2664(56) | 2057(57) | |

| High education | 1781(46) | 2094(44) | 1551(43) | p =0.15 |

| Low employment‡‡ | 1975(51) | 2522(53) | 1876(52) | |

| High employment | 1897(49) | 2236(47) | 1731(48) | p=0.013 |

| Low life expectancy | 1892(49) | 2565(54) | 1963(55) | |

| High life expectancy | 1980(51) | 2193(46) | 1645(45) | p <0.001 |

| Comorbidity scores | ||||

| CCI ≠0 [ N(%) ] | 236 (6) | 271 (6) | 268 (7) | p <0.001 |

| 1≤CCI ≤4 [ N(%) ] | 120 (3) | 171 (4) | 195 (5) | p <0.001 |

| CCI ≥5 [ N(%) ] | 116 (3) | 100 (2) | 73 (2) | p=0.005 |

| CDS [Median (IQR) ]§ | 984(381,1734) | 963(344,1377) | 1026(381,2255) | p <0.001 |

Numbers are total number of new entrants at each period;

Kruskal-Wallis Test used for differences in medians for age and CDS. Chi-Square test used for the rest off variables (categorical variables);

Age at treatment entry;

Urban is defined as a Local Health Area containing a city with more than 50,000 residents;

SES variables are ecological variables aggregated at the Local Health Area level, measured by % of neighbourhood population;

Low income (education) neighbourhoods are defined as those Local Health Areas within which incidence of low income(education) is higher than the median of the incidence of low neighbourhood level income(education) in 2001 British Columbia census(26) where median of low incidence of income(education) was 13.8%(24.1%);

Low life expectancy(employment) neighborhoods are those Local Health Areas which the expected life expectancy(employment rate) of their people is lower than the median of this SES variable in all British Columbia in 2001 census (21) where median for life expectancy (employment rate ) were 80.5(65.2);

Numbers in the parenthesis after median are interquantiles (Q1, Q3).

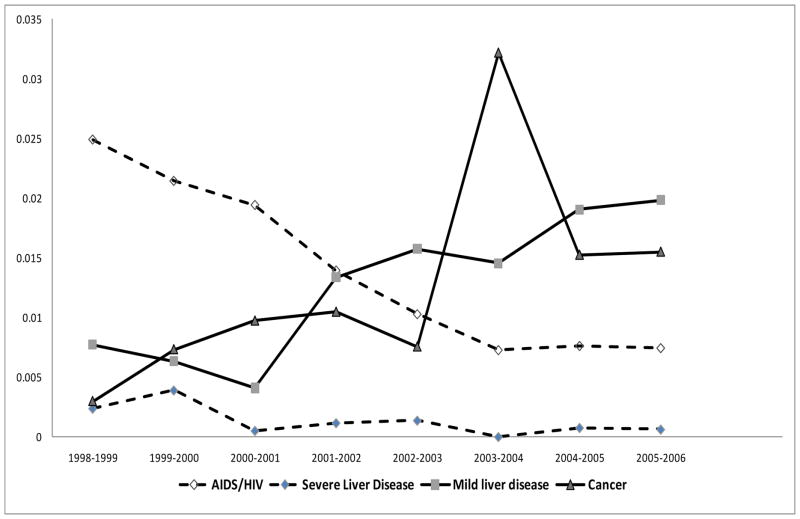

In terms of medical comorbidity, the proportion of clients with non-zero Charlson scores (CCI) increased over the study period (2% increase from second to third period, p-value<0.01). The mean CDS score of new participants has also increased (47.5 increase in mean CDS from second to third period, p-value<0.01). Percentages of first-time entrants with moderate CCI, 1≤CCI ≤4, increased from first to third period by 2.3%, while percentage of high CCI patients decreased by 1%. Figure 2 depicts the proportions of first-time entrants with four major diseases, as indicated by most responsible diagnoses in hospitalizations in the year prior to entry, and their annual trend among first-time entrants in MMT program. These four diseases were selected as these are the highest prevalent diseases amongst first-time entrants over the study period (i.e. prevalence of HIV (11%), Cancer (10%), and Mild liver disease (10%)). The proportion of patients with HIV/AIDS and sever liver disease (mostly hepatitis C), with highest weight in CCI calculation (weight=6), was decreasing, while the proportion of other complications such as mild liver disease (weight=1) and cancer (weight=2) was increasing over time.

Figure 2.

Proportion of first-time entrants to MMT with four major diseases, as indicated by most responsible diagnosis in hospitalizations within one year of treatment entry: AIDS/HIV and severe liver disease (Dashed line) vs. Cancer and Mild liver disease (Solid line); during the study period (1998–2006), as indicated through hospitalization records.

The result of regression models for both the CDS and Charlson scores were presented in Table 2. The mean CDS scores of first-time MMT entrants increased by 21.95(95% CI= [12.96, 30.94]) on the CDS-II scale per year, controlling for other covariates. Further, odds of having a patient with moderate CCI (1≤CCI ≤4) in MMT program as opposed to a patient with zero CCI increased by 9% per year, while the adjusted odds of having a patient with high CCI (CCI>=5) decreased by 13 % annually. Among all the patients with CCI>=5, 90% had HIV, 5% with sever liver diseases (Hepatitis C and B) and 5% had combination of several moderate comorbidities.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for CDS (Chronic disease score) and CCI (Charlson Comorbidity index) regression models

| Outcome: Chronic Disease Score * | Outcome: Charlson Comorbidity index ** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Coefficient estimate (95% CI) | P-value | OR(95% CI)† (1≤CCI≤4)vs(CCI=0) |

P-value | OR(95% CI)†† (CCI ≥5) vs (CCI=0) |

P-value | |

| Calendar year | 20.50 (11.77, 29.24) | <.0001 | 1.09(1.04,1.13) | <.0001 | 0.87(0.83,0.93) | <.0001 |

| Frailty term*** | −18.85( −101.45, 63.74) | 0.65 | 1.43(0.94,2.16) | 0.09 | 3.87(2.29,6.57) | <.0001 |

| Female gender | 560.13 (509.77,610.49) | <.0001 | 2.32(1.91,2.82) | <.0001 | 1.84(1.43,2.35) | <.0001 |

| Age‡ | 30.02 (27.84,32.2) | <.0001 | 1.06(1.06,1.07) | <.0001 | 1.08(1.07,1.09) | <.0001 |

| Urbancity‡‡ | −188.91(−258.4,−119.45) | <.0001 | 0.67( 0.51,0.89) | <0.01 | 1.10(0.72,1.69) | 0.66 |

| SES‡‡‡ | ||||||

| Health | −3.92 (−16.02, 8.17) | 0.52 | 0.99(0.93,1.05) | 0.70 | 1.05(0.97,1.13) | 0.25 |

| Income | −1.04 (−4.43,2.36) | 0.55 | 1.01(0.99,1.03) | 0.28 | 1.04(1.02,1.06) | <.001 |

| Education | 3.32 (1.11, 5.54) | <0.01 | 1.00(0.99,1.02) | 0.54 | 1.04(1.02,1.05) | <.0001 |

| Employment | −2.08 (−7.03, 2.86) | 0.41 | 1.02(0.99,1.04) | 0.17 | 0.99(0.96,1.02) | 0.51 |

Generalized linear regression model, specified with identity link, gamma distribution and CDS-II score as the outcome;

Multinomial logistic regression model with three levels of response variable: (1)CCI=0, (2) 1≤CCI ≤4, (3)CCI ≥5;

Random intercept of treatment is the individual-frailty term from the treatment model on the same data discussed in Nosyk et al. (28);

Odds ratio(95% Confidence interval) of low CCI vs. zero CCI;

Odds ratio(95% Confidence interval) of high CCI vs. zero CCI;

Age at treatment entry;

Urban is defined as a Local Health Area containing a city with more than 50,000 residents based on 2001 BC census data(26).;

SES variables are ecological variables aggregated at the Local Health Area level, measured by % of neighbourhood population based on 2001 BC census data(26).

They include: Health (life expectancy at birth), income (incidence of low income defined as annual income of less than 30,000$), education (incidence of low education defined as percentage of 18 year olds without high school diplomas) and employment rate (labour force participation rate of adults).

In addition to calendar year, sex and age at entrance was also significantly associated with all comorbidity measures. Females were 2.3 times as likely as males to have a moderate CCI, while each year of age at entry to program was associated with 6% and 8% increase in odds of having moderate and high CCI, respectively. Urban status was significantly associated with CDS and moderate Charlson score (1≤CCI ≤4), while the frailty term, low income and low education SES variables were significantly associated with high Charlson score. The significance of the coefficient for the random-effects frailty term in high Charlson score indicates that the unmeasured characteristics captured within this term were associated with baseline comorbidity among high CCI patients.

Discussion

During the rapid expansion of the BC Methadone program from 1998–2006 there were important changes in the characteristics of first-time entrants. Finally, we found that the level of treated and moderate medical comorbidity, as measured by CDS and moderate Charlson score(1≤CCI ≤4), was increasing independent of other potential changes in patient demographics. At the same time, the level of severe medical comorbidity, as measured by high Charlson score (CCI≥5), decreased over time among first-time entrants. As 95% of high Charlson scores patient either had HIV or severe liver problems (i.e. hepatitis C or B), we can deduct that except for HIV and hepatitis C, level of comorbidity increased among first-time entrants to MMT program. This indicates that the BC Methadone program was able to reach progressively more marginalized clients with higher levels of medical comorbidity over time since 1998, two years after its inception. In fact, except for HIV and sever liver diseases, we have seen an increasing trend among major diseases present in first-time entrants such as mild liver disease, chronic pulmonary disease, cancer and diabetes as defined in calculation of Charlson score (26).

Further, the mean age of first-time entrants and percentage of females increased, while more patients from rural areas entered treatment in BC for the first time. Having more patients from rural areas in recent years has positive implications in terms of successful treatment expansion in BC. In terms of neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status variables, we have seen a significant increase in the share of lower education and lower life expectancy neighbourhoods in the cohort of first-time entrants while the share of lower income and lower education increased in early years and stabilized in recent years. This shows increasing accessibility of MMT through lower SES neighbourhoods. It has been noted that, for the early years of expansion in BC, methadone provision was unevenly distributed across the province (18); many lower SES neighbourhoods across BC did not have a prescribing physician, and physicians in some areas had to restrict their MMT caseloads so as not to overwhelm their family practices (18). Although, it may still be a problem for BC MMT, in terms of patients’ characteristics, the results of this study show an increase in number of first-time entrants into MMT for marginalized patients in terms of rural status and lower SES neighbourhoods. It is important to note that our study, based on health administrative databases, can only capture the supply of treatment provided rather than the demand (and unmet demand) for treatment. Therefore, we can state that more individuals have accessed treatment over the study period and do not infer facts regarding the accessibility of MMT program.

Level of severe medical comorbidity, as measured by high Charlson score (CCI≥5), decreased over time among first-time entrants. This is largely due to the fact that proportion of first-time entrants with HIV/AIDS and severe liver disease (weight of 6 and 3 in CCI calculations) had a decreasing trend among first-time entrants to MMT throughout the study period as depicted in Figure 2. This can be due to the fact that severs cases among first-time entrants into MMT (including those with HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C patients) have accessed treatment in earlier calendar years. Recent report from the office of the provincial helath officer (34) has presented the decrease of HIV incident among Injection Drug Users (IDU’s) in BC, mostly after 2000. This report discussed several possible reasons including initiation of harm reduction program in 2002 and other services for provision of HIV/AIDS across BC.

Brands et al (20) found a downward trend in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C among first-time entrants which is in accordance with the results of our study. They concluded that higher profile patients (i.e. more stable patients) entered MMT over time. Our study indicated that while the percentage of HIV/AIDS and sever liver diseases (including hepatitis C and B) may have declined over time in BC, the aggregate trend of comorbidity level measured by Charlson index is increasing. On the other hand, the socioeconomic status measured by Brands et al. (20) is on the individual level, while ours are on the neighbourhood level. As a result, they observed an increasing trend in profile of first-time entrants in terms of education and employment status while we have seen the increase of participation from neighbourhoods with lower profile categories in terms of education and life expectance at birth.

The results of this study have important policy implications for BC Methadone program administrators and treatment providers. As MMT is available to patients with higher comorbidity levels as measured by CDS and Charlson score in BC, there is a greater need to integrate primary care with MMT. Providing primary care to MMT patients will reduce the demand placed on emergency rooms and hospitalization costs (21; 35). In addition, integrating MMT with primary care could lead to pragmatic interventions to identify patients in addiction treatment who are at risk for several medical conditions and improve the associated medical comorbidities (7; 35). As discussed in the 2009 revision of methadone maintenance handbook for authorized physicians in BC (17), patients should be screened for major comorbid conditions including hepatitis C, HIV/AIDS and mental health issues, in addition to the initial assessment for entry to methadone maintenance program and regular urine drug screening. However, aside from provision of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C in some of the MMT centers, there are no minimum requirements, guidelines or formal protocol for provision of medical care for methadone clients and office-based programs in BC (17; 35).

Result of our study and others (36) shows that one of the main features of the target consumers and recent first-time entrants of the current practice in BC are their high comorbidity levels. MMT services in BC are provided through a complex system with three major components of office-based (family physicians), multidisciplinary models (group practice) and private clinics (18). Community health models that provide several health and social services with group practice approaches are types of multidisciplinary models that have been discussed to provide better treatment outcome (21; 35). It is out of the scope of this study to relate comorbidity level of patients and their characteristics to the type of treatment modalities. However, our study provides evidence that comorbidity level of patients are increasing and therefore linking MMT with primary healthcare reform initiatives such as family health teams or community health services would significantly benefit the MMT program and optimize its expansion.

Few recent studies – and none in Canada – have evaluated the integration of MMT and primary care. Fareed et al. (10) demonstrated how adding an onsite health screening and brief health counselling by a team consisting of an addiction psychiatrist, a social worker, a nurse, and an addiction therapist contribute to improved treatment outcomes and management of hepatitis C, diabetes, smoking, and cardiovascular comorbidities among MMT patients in a US veteran methadone treatment clinic.

Our study was not free of limitations. The outcome measures considered in this study represent distinct dimensions of comorbidity status, each with their own limitations. Given that only treated co-morbidity is captured in CDS, it may underestimate the true comorbidity while our study population may not be getting treated for all of their illnesses. A further complication with the CDS is the potential for non-medical prescription drug use. In addition, the parameter estimates in multivariate analyses on CDS scores at least partly reflect an underlying characteristic indicating the desire and ability to acquire treatment. The Charlson index (CCI) is likely not as sensitive as CDS, but more specific (i.e. CDS is sensitive to change in age and prescription drugs that change more in time, while CCI is based on hospitalization data and is less likely to change over a one-year period). A further limitation of CCI in this context was the fact that it does not capture mental health disorders as it was primarily constructed to adjust for risk of mortality (25). As noted in Darke et al (6), there is a great deal of evidence that indicates that people who are dependent on opioids experience high rates of mental health disorders compared to the general population.

The primary finding of this study was that during the study period of 1998–2006, the composition of first-time entrants in the BC Methadone treatment became more heavily weighted toward patients with higher disease severity (except for HIV and hepatitis C) and lower neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status in terms of education and life expectancy. We have shown that high Charlson score of first-time entrants in MMT has decreased over time, almost entirely because of a reduction in the proportion of patients with HIV/AIDS and sever liver diseases including hepatitis C and B. In fact, first-time entrants into BC MMT are progressively higher functioning patients (due to lower rate of HIV/AIDS and sever liver diseases), while they presented with progressively higher level of medical comorbidity throughout the study period. This is due to an increase in proportion of first-time entrants with diseases such as mild liver diseases, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes and cancer. The characteristics of patients entering MMT are frequently cited as determinants of successful treatment outcome (35; 36) and also dictate their need for additional health services. Despite the frequency of comorbid medical conditions among patients in methadone maintenance treatment, these individuals often receive inadequate medical care (7; 9). The results of this study emphasize the necessity of integrating medical care with MMT and the need for regular screening for medical comorbidities, counselling and referral for relevant medical treatments for MMT patients. Doing so could decrease morbidity, mortality and long-term health care costs.

Acknowledgments

Behnam Sharif is supported by the Centre for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences; Bohdan Nosyk is a CIHR Bisby Postdoctoral fellow, and is also supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. We thank Dianne Calbick and Marie Skilling for their administrative assistance. Centre for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences, Providence Health Care Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Footnotes

Seventeen Diseases [and their weights] used in calculation of Charlson comorbidity Index (CCI) are: AIDS/HIV [w=6], Metastatic Carcinoma[w=6], Moderate or Severe Liver Disease[w=3], Cancer[w=2], Renal Disease [w=2], Paraplegia and Hemiplegia[w=2], Diabetes with complications [w=2], Diabetes without complications[w=1], Mild Liver Disease[w=1], Peptic Ulcer Disease[w=1], Connective Tissue Disease-Rheumatic Disease[w=1], Chronic Pulmonary Disease[w=1], Dementia[w=1], Cerebrovascular Disease[w=1], Peripheral Vascular Disease[w=1], Congestive Heart Failure[w=1], Myocardial Infarction[w=1].

References

- 1.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002;(4):CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamieson Beals, Lalonde and Associates, Inc. Litrature review Methadone Maintenance Treatment. for the office of Canada’s Drug Strategy. Health Canada; 2007. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/pubs/adp-apd/methadone/index-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degenhardt L, Randall D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, Burns L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: risk factors and lives saved. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009 Nov;105(1–2):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO position paper Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV / AIDS prevention. World Health Organization, United Nations office on Drugs and crime. UNAIDS; 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/en/PositionPaper_English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah NG, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Stambolis V, Johnson L, Nelson KE, et al. Correlates of enrollment in methadone maintenance treatment programs differ by HIV-serostatus. AIDS (London, England) 2000 Sep;14(13):2035–43. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009080-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darke S, Ross J, Teesson M. The Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS): what have we learnt about treatment for heroin dependence? Drug and alcohol review. 2007 Jan;26(1):49–54. doi: 10.1080/09595230601036986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amato L, Davoli M, Perucci Ca, Ferri M, Faggiano F, Mattick RP. An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2005 Jun;28(4):321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell J, Butler B. Health Care Utilization and Morbidity Associated With Methadone and Buprenorphine Treatment. Heroin Addiction And Related Clinical Problems. 2010;10(2):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darke S, Kaye S, Duflou J. Systemic disease among cases of fatal opioid toxicity. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2006 Sep;101(9):1299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fareed A, Musselman D, Byrd-Sellers J, Vayalapalli S, Casarella J, Drexler K, et al. On-site Basic Health Screening and Brief Health Counseling of Chronic Medical Conditions for Veterans in Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Journal of addiction medicine. 2010 Sep;4(3):160–166. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181b6f4e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard AA, Klein RS, Schoenbaum EE, Schoenbaumr EE. Associaton of Hepatitis C infection and Antretroviral Use with Diabetes Mellitus in Drug Users. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;36(10):1318–1323. doi: 10.1086/374838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim TW, Alford DP, Malabanan A, Holick MF, Samet JH. Low bone density in patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2006 Dec;85(3):258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim TW, Alford DP, Holick MF, Malabanan AO, Samet JH. Low Vitamin D Status of Patients in Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2009 Sep;3(3):134–138. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31819b736d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popova S, Rehm J, Fischer B. An overview of illegal opioid use and health services utilization in Canada. Public health. 2006 Apr;120(4):320–8. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer B. Prescriptions, power and politics: the turbulent history of methadone maintenance in Canada. Journal of public health policy. 2000 Jan;21(2):187–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson JF, Warren LD. Client retention in the British Columbia Methadone Program, 1996–1999. Canadian journal of public health Revue canadienne de santé publique. 1999;95(2):104–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03405776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Methadone maintenance handbook. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia; 2009. www.cpsbc.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reist Dan. Analysis and Recommendations. University of Victoria, Center for addictions research BC; report for Ministry of Healthy Living and Sport; 2010. May, Methadone Maintenance Treatment in British Columbia, 1996–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strike CJ, Urbanoski K, Fischer B, Marsh DC, Millson M. Policy Changes and the Methadone Maintenance Treatment System for Opioid Dependence in Ontario, 1996 to 2001. J Addict Dis. 2005;24(1):39–51. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brands B, Blake J, Marsh D. Changing patient characteristics with increased methadone maintenance availability. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2002 Mar;66(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart AN, Chair Longwood Publishing company. Report of the Methadone Maintenance Tretament Practices Task Force. Deputy Minster of health and Long-term Care; Ontario, Canada: Mar, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrill JO, Jackson TR, Schulman Ba, Saxon AJ, Awan A, Kapitan S, et al. Methadone medical maintenance in primary care. An implementation evaluation. Journal of general internal medicine. 2005 Apr;20(4):344–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PharmaNet: Ministry of Health Services. [Accessed January 2011];Information available from. http://www.health.giv.bc..ca/pharmacare/pharmanet/netindex.html.

- 24.Population Data BC. Multiuniversity platfrom- BC’s pan-provincial population health data services. [Accessed January 2011];Informaion available from. http://www.popdata.bc.ca.

- 25.Schneeweiss S, Maclure M. Use of comorbidity scores for control of confounding in studies using administrative databases. International journal of epidemiology. 2000 Oct;29(5):891–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deyo R, Cherkin D, Ciol M, Adapting A. Clinical Comorbidity Index for Use With ICD-9-CM Administrative Database. Journal Of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Needham D, Scales D, Laupacis a, Pronovost P. A systematic review of the Charlson comorbidity index using Canadian administrative databases: a perspective on risk adjustment in critical care research. Journal of Critical Care. 2005 Mar;20(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Decker FH, Luo H, Geiss LS, Pearson WS, Saaddine JB, et al. Trends in the prevalence and comorbidities of diabetes mellitus in nursing home residents in the United States: 1995–2004. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010 Apr;58(4):724–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.BC Census and Vital Statistics Agency. [Accessed : 10 Janaury 2011];Information available. from : http://www.vs.go..bc.ca/stats.

- 30.Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public health reports. 2002 Jan;117(Suppl):S135–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nosyk B, MacNab YC, Sun H, Fischer B, Marsh DC, Schechter MT, et al. Proportional hazards frailty models for recurrent methadone maintenance treatment. American journal of epidemiology. 2009 Sep;170(6):783–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muth BO. Beyond SEM: General Latent Variable Modeling. Behaviormetrika. 2002;29(1):81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical care. 2005 Nov;43(11):1130–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Report from the Office of the Provincial Health Officer, P.R.W. Kendall., Provincial Health Officer. British Columbia: Mar, 2011. [Accessed May, 2011]. Decreasing HIV Infections Among People Who Use Drugs By Injection In British Columbia: Potential explanations and recommendations for further action. Available online: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2011/decreasing-HIV-in-IDU-population.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jamieson Beals, Lalonde and Associates, Inc. Best practices Methadone Maintenance Treatment. [Accessed January 2011];Office of Canada’s Drug Strategy, health Canada. 2007 Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/pubs/adp-apd/methadone-bp-mp/intro-eng.php.

- 36.Nosyk B, Marsh DC, Sun H, Schechter MT, Anis AH. Trends in methadone maintenance treatment participation, retention, and compliance to dosing guidelines in British Columbia, Canada: 1996–2006. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2010 Jul;39(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]