Abstract

This article highlights findings from an evaluation that explored the impact of mobile versus clinic-based testing, rapid versus central-lab based testing, incentives for testing, and the use of a computer counseling program to guide counseling and automate evaluation in a mobile program reaching people of color at risk for HIV. The program’s results show that an increased focus on mobile outreach using rapid testing, incentives and health information technology tools may improve program acceptability, quality, productivity and timeliness of reports. This article describes program design decisions based on continuous quality assessment efforts. It also examines the impact of the Computer Assessment and Risk Reduction Education computer tool on HIV testing rates, staff perception of counseling quality, program productivity, and on the timeliness of evaluation reports. The article concludes with a discussion of implications for programmatic responses to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s HIV testing recommendations.

In 2002 a Seattle, Washington, community-based organization, People of Color Against AIDS Network (POCAAN), began the Health on Wheels (HOW) mobile HIV counseling and testing program, in collaboration with a volunteer medical director from the University of Washington Department of Family Medicine and with technical support provided by Public Health Seattle and King County. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded the program for 3 years as a demonstration project, and the King County Council subsequently funded it for an additional 2 years. The program design recognized that people of color at risk for HIV need convenient, culturally appropriate access to HIV counseling, testing and referral services, and it attempted to integrate new testing and counseling strategies (Spielberg et al., 2003, 2005) to ensure the program’s acceptability and effectiveness. This study presents evaluation data from continuous quality improvement efforts undertaken between 2002 and 2007 to answer the following questions: Does Mobile testing reach a different population then clinic based health department testing?; Does offering a $10 incentive increase the identification of new positives?; How do alternative testing strategies impact program effectiveness?; How does interactive computer counseling impact counseling quality, program productivity and evaluation capabilities?

Of the estimated 56,000 new HIV infections each year in the United States, 63% occur among Black and Hispanic/Latino populations (CDC, 2010). In King County, Washington, at the time this program was developed, HIV rates among minorities had been growing at an alarming rate (Hopkins, 2001). According to 2000 census data, ethnic minorities were 21% of the population in King County but represented 41% of AIDS cases in 2000, up from 15% in 1986. The evidence suggested that existing models of HIV testing and counseling in clinical settings had reached only a portion of the communities of color at risk for HIV in Seattle. An application was awarded to develop a mobile counseling and testing program to reach people of color based on local research that identified optimal HIV counseling and testing strategies in outreach settings (Spielberg, 2005).

Iterative evaluation was possible within this program owing to the incorporation initially of paper outreach logs and risk assessments and made easier by the later use of the CARE tool that collected complete data in real time and automated reports. The evaluation findings presented in this article provide new information describing the potential design benefits of mobile testing, rapid testing, incentive use, and interactive computer counseling to facilitate automated evaluation and to improve the quality and productivity of mobile HIV counseling and testing programs.

PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

The HOW program was designed, based on local research (Spielberg, 2003; Spielberg et al., 2005), to use a mobile-testing van staffed by two recruiters and two testers who initially offered a variety of testing options (oral fluid, rapid blood, standard blood, urine) to people of color at high-risk venues, such as bars and parks where people at high risk for HIV congregate. Initially, the program did not offer monetary incentives and used a standard SPSS database of recruitment and risk assessment data to provide program evaluation.

With time, several program improvements were implemented and evaluated. To improve testing acceptance rates, monetary incentives ($10) were offered for HIV testing. Although these incentives may have induced some people to be tested repeatedly, staff discouraged testing more frequently than every 3 months. Follow-up of HIV-positive individuals through health department tracking determined first time HIV diagnosis rates. Staff used confidential lists of names to avoid duplicate testing. To improve rates of receipt of test results, the program evolved to offer only rapid HIV testing, first by finger stick and when approved, using the OraQuick Advance oral fluid rapid HIV test. The program demonstrated that they were able to reach people of color at risk for HIV; however, data management and reporting were problematic. Program staff did not have the expertise to manage a standard database, and so generating program reports was difficult and time consuming.

To facilitate data entry, a simplified ACASI computer program (QDS, NOVA Research Company) was initially used so that all staff could enter outreach testing data. However, the staff prioritized spending their time offering services to clients, so it often took months before data were entered. The program also had to hire an outside consultant to generate program reports. There was such delay between data collection and evaluation reports that program staff were unable to use the evaluation data in any meaningful way, and the associated paperwork made staff dislike the evaluation process.

Staff turnover was another problem. Salaries in community-based organizations were lower than those in health department and clinical settings; thus, trained staff frequently left to take other opportunities. With high rates of staff turnover it was difficult to keep up with training needs and to ensure that quality counseling and referrals were being provided.

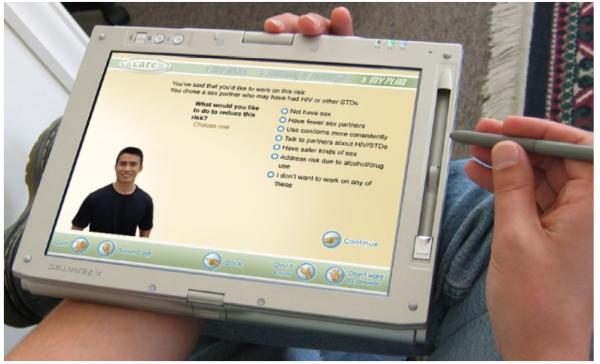

In January 2006 the program implemented the Computer Assessment and Risk Reduction Education (CARE) tool for routine use with rapid HIV counseling and testing. CARE is an interactive multimedia computer tool that allows patients to receive individualized risk assessment, for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) information about rapid HIV testing, and provides evidence-based HIV/STI risk reduction counseling (Figure 1). A typical CARE session has six elements: (a) anonymous log-in, welcome, and selection of counselor; (b) rapid HIV test consent; (c) risk assessment; (d) tailored feedback and counseling, including skill-building videos; (e) an individualized risk reduction plan; and (f) a printed report and referrals, if applicable. The tool has been designed to recognize clients for longitudinal care, so that even when in the field, staff are able to pull up past risks and behavior change plans to determine progress made and supplement counseling.

FIGURE 1.

The CARE tool Provides Automated Interactive HIV Counseling and Evaluation.

Although the CARE tool had been used successfully as a client-administered audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) tool with rapid HIV testing in clinic settings, POCAAN staff decided to use it with clients to guide and enhance their counseling, to eliminate paperwork and subsequent data entry, and to provide clients with a printed summary of their risks, risk reduction plan, and referral needs.

Automated reports were generated for daily quality assessment and weekly reports for the health department. HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation reports were also developed in response to CDC reporting requirements.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

When the program was first implemented, the primary evaluation question was “Does the mobile program reach different populations than the health department clinic-based testing and counseling programs?” (Table 1). During the initial evaluation period (April 2001–April 2002), POCAAN tested 610 people, and the health department tested 1,838 people. Evaluation of POCAAN data showed that its programs not only reached a greater percentage of people of color (84% vs. 29%, p < .001) and first-time testers (40% vs. 22%) than the health department, but it also tested more people younger than 20 years old (19% vs. 3%, p < .001), people with a high school education or less (65% vs. 19%, p < .001), substance users in past year (91% vs. 24%, p < .001), and binge drinkers in past month (36% vs. 31%, p < .05). Even when restricting the evaluation population to men of color who have sex with men, POCAAN reached a population that was less educated (44% high school or less vs. 20%, p < .001), younger (16% younger than 20 vs. 4%, p < .001), more likely to use substances (85% vs. 29%) and have unprotected sex while high on drugs or alcohol (39% vs. 18%, p < .001), and more likely to be first-time testers (28% vs. 16%, p < .05). The prevalence of HIV in this evaluation was not significantly different than the health department testing sites, but a different population was identified.

TABLE 1.

ITERATIVE EVALUATION OF A MOBILE HIV COUNSELING AND TESTING PROGRAM

| (1) Does mobile testing reach a different population than clinic-based health department testing? |

| Using culturally similar outreach workers in a mobile program targeting high risk venues reached populations that were almost twice as likely to have never tested and significantly more likely to have had unprotected anal or vaginal sex since their last test. |

| Health Department Testing (n = 1838) |

| People of color – 29% |

| Never tested – 22% |

| Unprotected anal or vaginal sex since last HIV test – 54% |

| CBO Testing (n=610) |

| People of color – 84% (p < 0.001) |

| Never tested – 40% (p < 0.001) |

| Unprotected anal or vaginal sex since last HIV test – 72% (p < 0.001) |

| (2) Does offering incentives increase identification of new positives? |

| A $10 incentive made the testing program four times more effective in reaching people at risk and identifying HIV cases: |

| No Incentive – 362 tested (5 HIV positive) |

| $10 incentive – 1437 tested (25 HIV positive) |

| (3) How do alternative testing strategies impact program effectiveness? |

| Offering only rapid testing made the testing program almost twice as effective as when oral fluid testing was offered in combination with other test strategies. |

| Oral fluid testing (n=829) – 55% received results |

| Rapid testing (n=1470) – 99% received results (p<0.001) |

| (4) How does interactive HIV computer counseling impact counseling quality, program productivity and evaluation capabilities? |

| CBO staff and health department payers appreciated the impact of the CARE tool: |

| Counseling Quality – Minimally trained counseling staff appreciated the CARE tool guiding them through all key components of counseling and felt that the program improved their ability to provide longitudinal counseling in the field, through bringing up past risk behaviors and counseling plans. |

| Program Productivity – With the CARE tool staff did not have to spend time in the office entering data, and so could spend more time out in the field reaching clients. |

| Timeliness of Evaluation Reports– Staff for the first time appreciated evaluation data because they received it in real time and were able to better tailor outreach. Program administrators appreciated the automated evaluation reports and for the first time were able to submit their reports on time to the health department and receive prompt payment. |

Next the study sought to determine, “How do alternative testing strategies impact program effectiveness?” Analysis of data initially showed that movie tickets and food did not appreciably increase program productivity. After community feedback was received, $10 incentives were offered and testing rates increased by a factor of 4 (362 in 2003 vs. 1437 in 2004), with five times as many new cases of HIV identified (5 in 2003 vs. 25 in 2004).

The next evaluation question asked, “Is it better to offer a variety of testing options or just rapid testing?” The evaluation data found that with rapid testing (n = 1,470), 99% of clients tested received results (p < .001) compared to 55% (n = 829) of clients who received the standard oral fluid test when a choice was given between testing strategies. Although the majority of people preferred to test with the OraSure oral fluid test that was sent to the central lab, because few returned for test results, the program determined that it was more effective to only offer the less acceptable strategy, rapid blood testing, so that people were able to get results during the initial visit. When the OraQuick Advance rapid oral fluid test became available, it allowed the program to offer both the most acceptable specimen collection method (oral fluid) as well as the most effective method for providing test results (rapid testing).

Finally, the study sought to determine, “How does interactive HIV computer counseling impact counselling quality, program productivity and evaluation capabilities?” (Table 1). In the first 3 months of CARE tool implementation, the program tested over twice as many clients per month compared to standard incented rapid testing (255/month vs. 120/month, p < .001). As the program evolved, the demographics of clients reached remained consistent with program goals, although males were more likely to be reached then females. In the first few months of testing using the CARE tool (n = 595), clients had the following attributes:

Males accounted for 70% of clients reached.

People of color accounted for 65% including 19% immigrants.

Nineteen percent were homeless.

Seventy-five percent screened positive for chemical dependency with 29% injection drug users.

Ninety-nine percent had had a risk since their last HIV test.

Nineteen percent had never been tested.

Their ages ranged from 15 to 76.

Their highest level of education achieved included 29% who had not attained a high school diploma and 47% who had achieved a High School diploma or GED.

The efficacy of the computer-assisted counseling has not yet been formally evaluated in the POCAAN population. However, it was modeled after the effective Project RESPECT counseling model that was shown to significantly lower the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (Kamb et al., 1998). An evaluation of the counseling plans that clients chose showed that all clients developed personal risk reduction plans: Nineteen percent chose abstinence, 23% chose fewer partners, 17% chose more condom use, 4% selected talking to their partner about HIV testing, 25% aimed to try safer kinds of sex, and 12% chose to decrease alcohol and drug use. Overall, 97% reported high confidence in their ability to complete their chosen plan, which has been correlated to behavior change in prior research.

Staff interviews were conducted (n = 5) to evaluate their perspective on the impact of the CARE tool on the quality of counseling provided, and on the ability of the program to generate timely reports so that funding reimbursement would not be delayed. Results from staff interviews revealed that the CARE tool had several effects on their outreach testing program (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Impact of Computer Counseling on Mobile Outreach Program—Staff Themes

| Counseling Improvements |

|---|

|

| Participant Acceptability |

|

| Administrative Improvements |

|

DISCUSSION

The CDC continues to promote expanding access to HIV testing among sexually active people in the United States (CDC, 2006). New guidelines for HIV testing in non-clinical settings are anticipated in 2011. As the program evaluation in Seattle showed, an increased focus on mobile outreach using rapid testing and information technology health tools may facilitate reaching populations unaware of their status who do not proactively seek out clinical services. The CDC also recommends simplifying the consent and counseling process when it presents a barrier to testing. However, many HIV prevention advocates are concerned that simplifying the consent process and counseling procedures may result in inadequate education and poor preparation of clients for receipt of HIV test results. Missed opportunities for HIV prevention is also a concern if in depth risk reduction counseling is eliminated. Use of a mobile health tool such as CARE allows the benefit of standardized consent and in-depth counseling with minimal staff training or time required.

In designing mobile HIV counseling, testing, and referral programs, the authors recommend using culturally similar recruiters, monetary incentives to increase testing acceptance, rapid oral fluid testing to ensure that clients get test results, and computer counseling tools such as CARE (http://www.ronline.com/care/) to improve the acceptability and productivity of the program, to ensure the quality of the counseling provided, and to allow real- time and effortless program evaluation. Promoting broad access to HIV testing without eliminating adequate consent and high-quality counseling may be possible, if these alternative strategies are adopted.

Contributor Information

Freya Spielberg, RTI International, San Francisco, CA..

Ann Kurth, New York University, College of Nursing, New York, NY..

William Reidy, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY..

Teka McKnight, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, TX..

Wame Dikobe, St. George’s University School of Medicine (SGUSOM) in Grenada, West Indies..

Charles Wilson, Director of POCAAN Health on Wheels, Seattle, WA..

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(RR14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention HIV in the United States. 2010 Updated July 2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/PDF/us.pdf.

- Hopkins S. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in Seattle-King County, Washington State. Unpublished overheads from the HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Program, Public Health; Seattle and King counties. WA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr., Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Association. 280:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberg F, Branson BM, Goldbaum GM, Lockhart D, Kurth A, Rossini A, et al. Choosing HIV counseling and testing strategies for outreach settings: A randomized trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2005a;38(3):348–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberg F, Branson B, Goldbaum G, Lockhart D, Kurth A, Celum C, et al. Overcoming barriers to HIV testing: Preferences for new strategies among clients of a needle exchange, an STD clinic and sex venues for MSM. Journal of AIDS. 2003;32(3):318–327. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200303010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberg F, Kurth A, Severynen A, Hsieh YH, Moring-Parris D, Mackenzie S, Rothman R. Computer-facilitated rapid HIV testing in emergency care settings: Provider and patient usability and acceptability. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011 doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3.206. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]