Abstract

This study outlines a drug delivery mechanism that utilizes two independent vehicles, allowing for delivery of chemically and physically distinct agents. The mechanism was utilized to deliver a new anti-cancer combination therapy consisting of piperlongumine (PL) and TRAIL to treat PC3 prostate cancer and HCT116 colon cancer cells. PL, a small-molecule hydrophobic drug, was encapsulated in poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles. TRAIL was chemically conjugated to the surface of liposomes. PL was first administered to sensitize cancer cells to the effects of TRAIL. PC3 and HCT116 cells had lower survival rates in vitro after receiving the dual nanoparticle therapy compared to each agent individually. In vivo testing involved a subcutaneous mouse xenograft model using NOD-SCID gamma mice and HCT116 cells. Two treatment cycles were administered over 48 hours. Higher apoptotic rates were observed for HCT116 tumor cells that received the dual nanoparticle therapy compared to individual stages of the nanoparticle therapy alone.

Keywords: Nanoparticle, Nanomedicine, Piperlongumine, TRAIL, Cancer, Therapy

INNOVATION

The drug delivery system presented in this article is unique because of the use of two distinct types of nanoparticles, rather than a single particle. The development of nanoparticle drug delivery systems has largely focused on advancing particle designs to improve delivery. The system outlined here instead utilizes two different types of nanoparticles to improve delivery. This feature allows for the independent administration and delivery of chemically distinct therapeutic agents. This is advantageous for multi-component treatments, as demonstrated here with the piperlongumine (PL) and TRAIL anti-cancer combination therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Differentiation between cancerous and normal cells remains a fundamental challenge to developing targeted treatments for cancer. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a therapeutic protein known to exhibit these desired selective properties. Initial studies in the mid-1990s demonstrated TRAIL’s ability to induce apoptosis in cancer cells while leaving non-cancerous cells unharmed1–4. The protein interacts with death receptors 4 and 5, which are known to be overexpressed on the surface of cancer cells1. Binding of TRAIL to the death receptors initiates a caspase-dependent pathway that ultimately leads to apoptosis1.

Despite the selective and lethal properties of TRAIL against cancer cells, the effect is not uniform across all cancer types. Certain cell lines, such as PC3 prostate cancer cells and Colo205 colon cancer cells, are known to be more sensitive to the effects of TRAIL compared to others5. HCT116 and HT29 colon cancer cells are examples of cell types that are known to be more resistant to TRAIL, which thus reduces the therapeutic effectiveness of the anti-cancer protein6,7. To overcome this limitation, a sensitization approach can be utilized, such as the coupling of TRAIL with an additional therapeutic agent. The additional agent sensitizes resistant cancer cells to the effects of TRAIL to ultimately increase the therapeutic effectiveness of the protein. This approach has been demonstrated with several drugs, including paclitaxel and bortezomib8–12.

Recent work has demonstrated the sensitizing activity of PL in conjunction with TRAIL13. PL is a small-molecule drug derived from the Indian long pepper plant and exhibits anti-cancer effects. Its therapeutic properties are derived from its ability to increase levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cancer cells14. The drug has been utilized as part of a novel combination therapy with TRAIL, and exhibits a therapeutic synergy with the anti-cancer protein13.

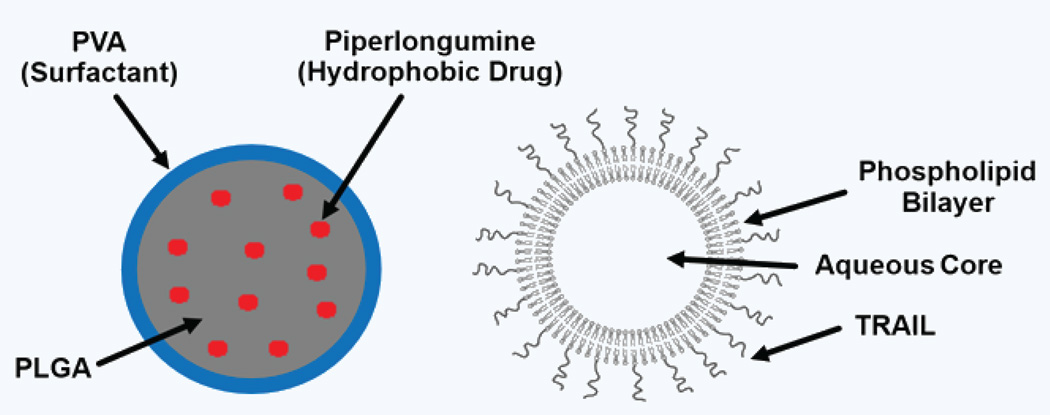

In this work, we describe a nanoparticle-based drug delivery mechanism developed for this combination therapy. Nanoparticle delivery platforms have been pursued for a variety of cancer therapies3,15–19. A number of studies focus on complex particle structures and designs aimed at improving delivery17–21. Our system utilizes a different approach through the use of a dual nanoparticle delivery mechanism (Fig. 1). Therapeutic components are administered through separate particles as opposed to delivering the agents in a single particle. Given PL’s hydrophobic nature, the drug is encapsulated in polymer-based nanoparticles comprised of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid; PLGA) and coated with a polyvinyl alcohol surfactant layer. TRAIL is chemically conjugated to the surface of lipid-based liposomes, leaving the protein free to interact with the death receptors on the surface of cancer cells. This study describes the formulation of both particles and testing of the therapeutic efficacy in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 1.

Dual nanoparticle delivery of PL and TRAIL. Piperlongumine (PL) was encapsulated in PLGA polymer nanoparticles. TRAIL was chemically conjugated to the surface of liposomes28.

RESULTS

Physiochemical nanoparticle characteristics

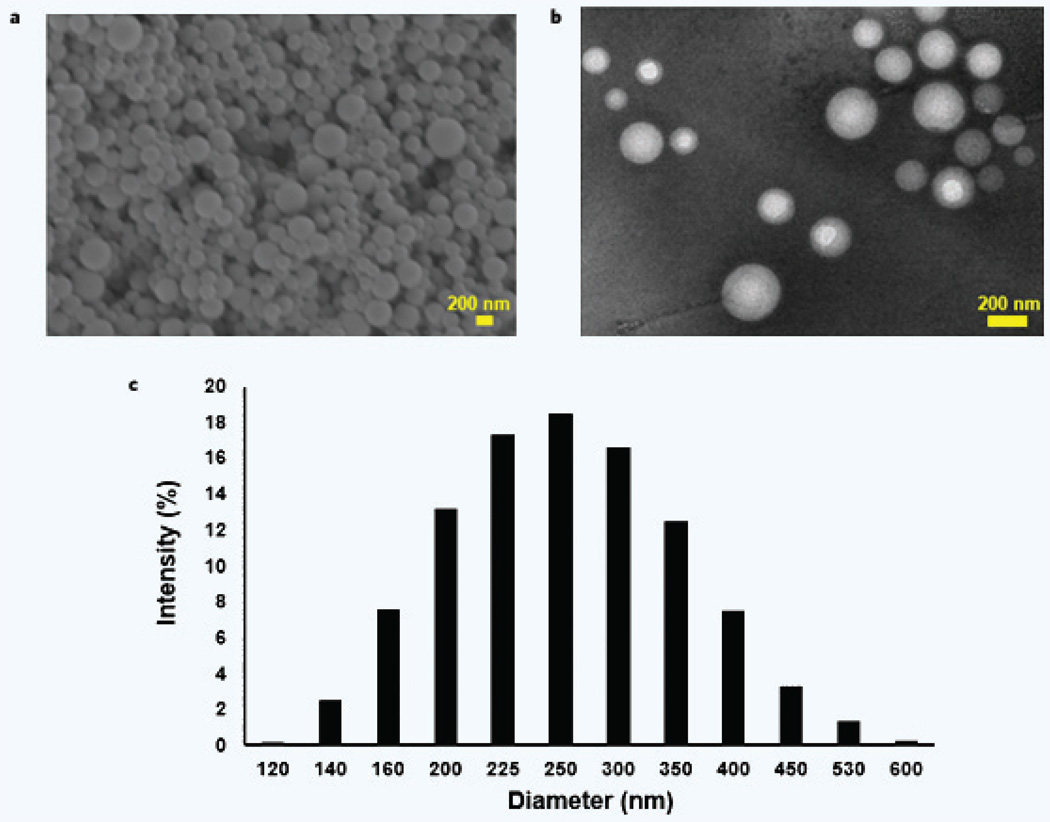

The single emulsion synthesis process produced PLGA particles 246.8 ± 78.6 nm in size with a zeta potential (ZP) of –1.55 ± 0.41 mV (Table 1). The particles were calculated to have 0.036 ± 0.002 mg of PL per mg of PLGA loaded during the emulsion synthesis. SEM and TEM imaging showed the spherical shape and the smooth featureless surface of the PLGA nanoparticles (Fig. 2). Drug release and particle breakdown are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Additionally, PLGA molecular weight was found to have no effect on PL loading in the nanoparticles, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Characterization of PL–PLGA nanoparticles and TRAIL–liposomes.

| Avg. size (nm)* | Avg. ZP (mV)* | Avg. PDI* | Drug loading* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA nanoparticles | 246.8 ± 78.6 | −1.55 ± 0.41 | 0.081 ± 0.017 | 0.036 ± 0.002 mg PL/mg PLGA |

| TRAIL-conjugated liposomes |

109.0 ± 49.2 | −3.11 ± 0.99 | 0.14 ± 0.012 | 0.18 ± 0.045 mg TRAIL/mg liposomes |

Presented values are the mean ± standard deviation; PDI = Polydispersity Index; ZP = Zeta Potential

Figure 2.

PLGA nanoparticle surface morphology and size distribution. SEM (a) and TEM (b) imaging shows the spherical shape of the PLGA nanoparticles. The particle surfaces appeared smooth and featureless. (c) The measured size distribution for the particles is shown.

TRAIL liposomes, after extrusion and chemical conjugation of TRAIL, were measured to have a size of 109.0 ± 49.2 nm and a zeta potential of −3.11 ± 0.99 mV. The liposomes were determined to be loaded with 0.18 ± 0.045 mg of TRAIL per mg of liposomes (Table 1).

Cellular interactions with nanoparticles

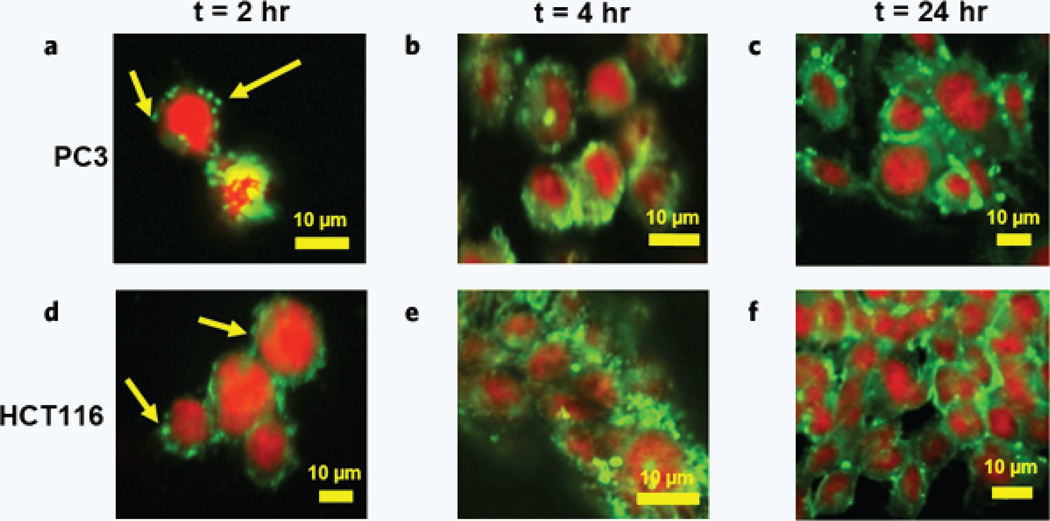

Confocal imaging was used to observe the interactions of PLGA nanoparticles with PC3 (Fig. 3a,b,c) and HCT116 (Fig. 3d,e,f) cancer cells. Particles were loaded with a green fluorescent dye, which was used to observe particle localization and breakdown after 2, 4, and 24 hours of incubation with the cancer cells. Cells were stained with a red nuclear staining dye.

Figure 3.

Cellular–PLGA nanoparticle interactions. Nanoparticle interactions with PC3 prostate cancer cells were observed using confocal microscopy after (a) 2, (b) 4, and (c) 24 hours of incubation. Nanoparticle interactions with HCT116 colon cancer cells were also observed after (d) 2, (e) 4, and (f) 24 hours of incubation. PLGA nanoparticles were loaded with Coumarin 6, a green fluorescent dye. Cells were stained with DRAQ5, a red nuclear staining dye. The localization and proliferation of the green Coumarin 6 dye were used to observe the location and extent of PLGA nanoparticle breakdown. Arrows indicate localized dye thought to be intact nanoparticles and/or particles that are in the early stages of breaking down.

In vitro therapeutic efficacy

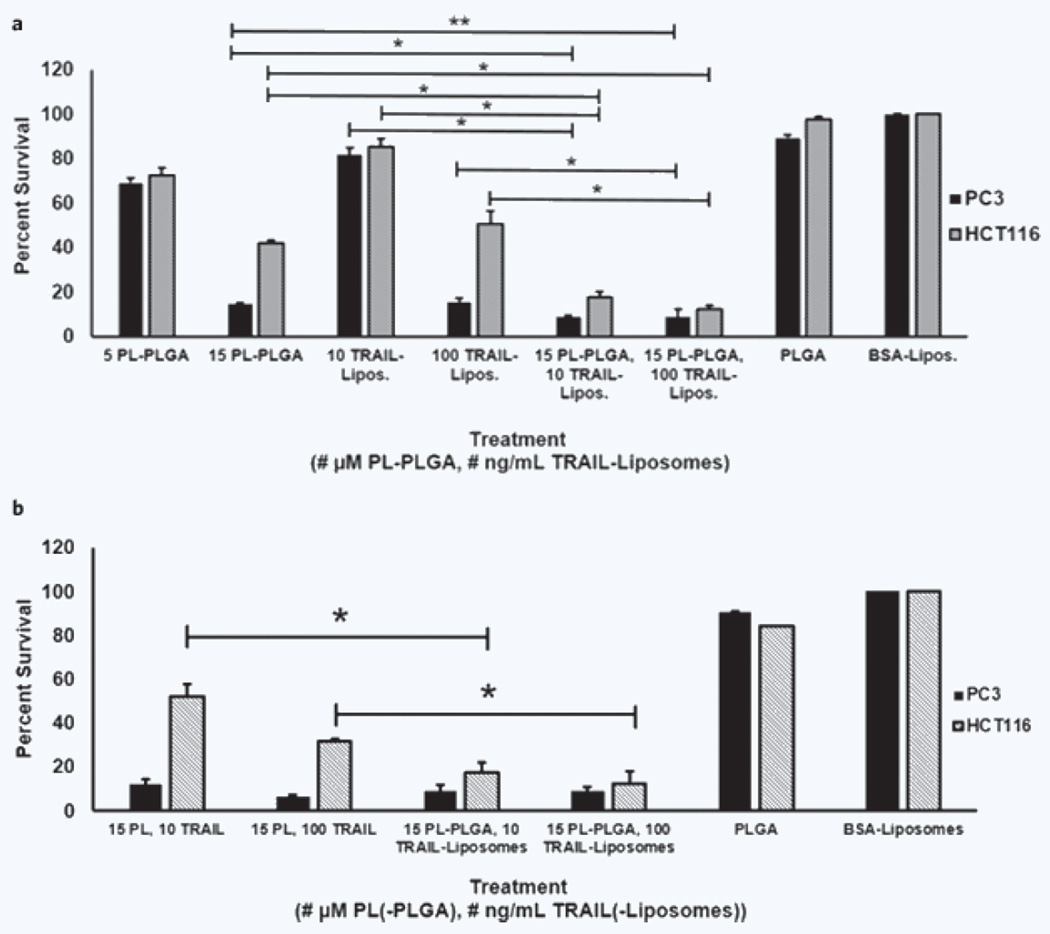

Cell survival after treatment varied with the respective therapeutic agent and administered dose (Fig. 4a). Control cells, which received empty PLGA nanoparticles and/or BSA coated liposomes, showed a significantly higher survival rate compared to cells that received the PL–PLGA and/or TRAIL–liposomes. PL–PLGA particles and TRAIL–liposomes were found to reduce cell survival in both PC3 and HCT116 cells when administered individually and in series as part of the two-stage sensitization therapy.

Figure 4.

In vitro efficacy of the dual nanoparticle therapy. HCT116 and PC3 cancer cells were treated with PL–PLGA, TRAIL–liposomes (Lipos.) and/or a combination of both for 24 hours. Cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. (a) HCT116 control cells (PLGA, BSA–liposomes) had a significantly higher survival rate compared to cells that received treatment (PL–PLGA and/or TRAIL–liposomes): p < 0.001, α = 0.01. A similar difference in survival rates was observed between PC3 control cells and cells that received treatment: both doses of the combination therapies and higher doses of the individual components (15 µM PL–PLGA and 100 ng/mL TRAIL–liposomes, p < 0.001, α = 0.01), low dosages of the individual components (5 µM PL–PLGA, 10 TRAIL–liposomes, p < 0.03, α = 0.05). *Significant difference between the combined PL-PLGA and TRAIL-liposome treatment compared to both of the individual components administered alone, p < 0.001, α = 0.01; **p < 0.02, α = 0.05. (b) The therapeutic effectiveness of PL and TRAIL were directly compared to PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes. HCT116 and PC3 cells were treated with PL or PL–PLGA for 24 hours, and then incubated with TRAIL or TRAIL–liposomes for an additional 24 hours. *Significant difference between the PL and TRAIL treatment compared to PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes for HCT116 cells, p < 0.001, α = 0.01.

Comparison of delivery mechanisms

To examine the utility of using the dual nanoparticle delivery mechanism, HCT116 and PC3 cells were treated with PL and TRAIL as well as PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes. Changes in cell morphology were observed for both cell lines after receiving the treatment. Cells that received both the nanoparticle-delivered therapeutics and the agents in solution (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c,e,f) were found to be reduced in size compared to control cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a,d). These morphological changes are characteristic of unhealthy cells and those that have undergone apoptosis. This was confirmed through an MTT assay. The survival rates of control cells were compared to cells that received the treatments (Fig. 4b). For PC3 cells, no significant difference was found between the agents administered in solution compared to those administered via the dual nanoparticle system. The dual nanoparticle therapy, however, was determined to be more effective against HCT116 cells compared to the therapeutics in solution. Additional trials comparing PL to PL–PLGA and TRAIL to TRAIL–liposomes are presented in Supplementary Information S3.

Mechanistic evaluation of the therapy

Death receptor expression was measured for HCT116 and PC3 cells treated with PLGA nanoparticles, PL, and PL–PLGA (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). Both PC3 and HCT116 cells treated with PL and PL–PLGA were observed to exhibit increased expression of DR5, compared to cells treated with PLGA nanoparticles. The strongest expression was exhibited by HCT116 cells treated with PL–PLGA, which was noted to be greater than DR5 expression of HCT116 cells treated with PL. β-tubulin was used as an internal control.

In vivo anti-tumor efficacy

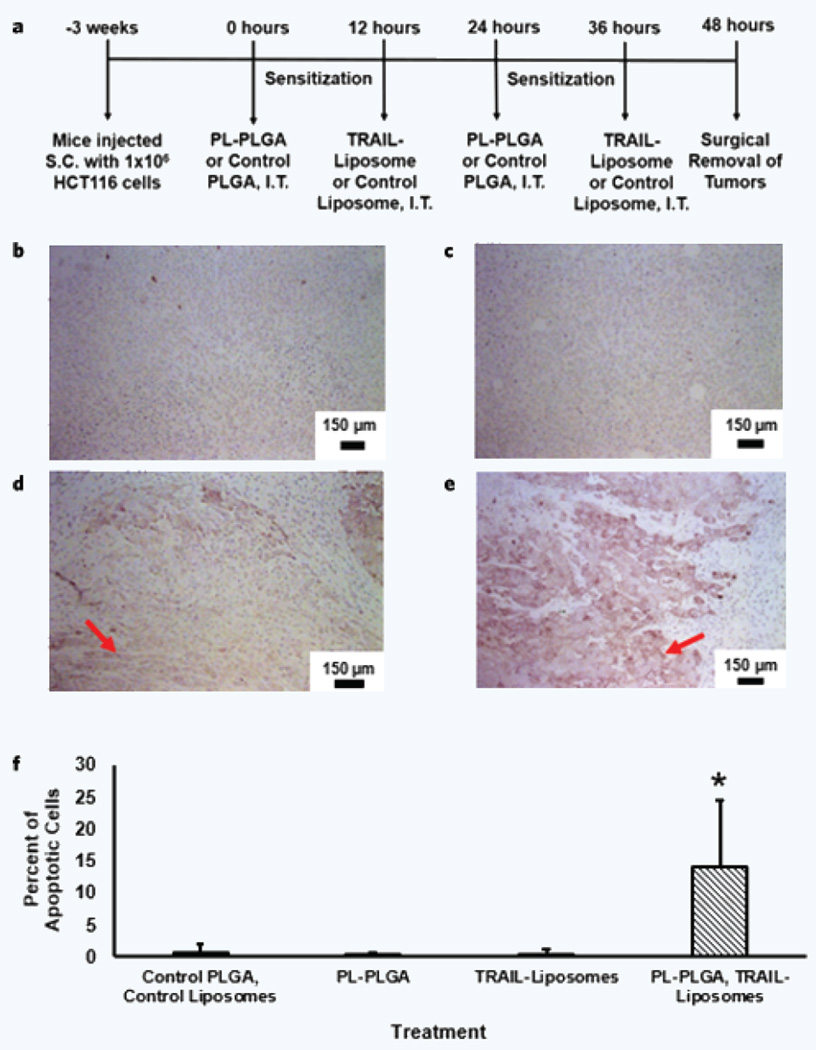

NOD-SCID gamma (NSG) mice were subcutaneously implanted with 1 × 106 HCT116 cancer cells. When the average diameter of tumors grew to 3–5 mm, approximately 3 weeks after implantation, NSG mice were intratumorally injected with empty PLGA particles/liposome buffer, PL–PLGA, TRAIL–liposomes, and PL–PLGA/TRAIL–liposomes at pre-clinically relevant dosages for two cycles as detailed in the Methods section (Fig. 5a). Staining of tumor cross sections allowed for visualization of apoptotic cells, as identified by a dark purple-brown coloration positive for active caspase-3. Active caspase-3 levels were nearly undetectable in tumors that received empty PLGA particles and liposome buffer, similar to tumors treated with PL–PLGA (Fig. 5b,c). In contrast, active caspase-3 was observed in cross sections from tumors treated with TRAIL–liposomes, indicating the presence of apoptotic cells (Fig. 5d). Darker coloration was observed to a greater extent in tumors treated with the two-stage therapy consisting of PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes (Fig. 5e). Image analysis of the tumor cross-sections found that tumors treated with PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes had a significantly higher number of apoptotic cells (Fig. 5f).

Figure 5.

Apoptotic staining of tumor cross-sectional slices. Subcutaneous tumors were surgically removed after treatment and slices of the mass were prepared on slides. The treatment cycle is outlined in (a), where s.c. is subcutaneous and i.t. is intra-tumoral. An apoptotic detection assay was applied to tumor cross sections for mice that received (b) PLGA and liposome buffer, (c) PL–PLGA, (d) TRAIL–liposomes, and (e) both PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes. Apoptotic tumor cells appear darker in coloration compared to non-apoptotic cells as a result of the staining procedure. Arrows indicate regions of apoptotic cells in the cross sections. (f) Detection and quantification of apoptotic signals in the cross sections from the collected tumors was conducted using the Aperio Positive Pixel Count algorithm. *Significant difference between the PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposome two-stage therapy compared to the control, PL–PLGA, and TRAIL–liposomes administered individually, p < 0.01, α = 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Nanoparticle physical characteristics and interactions with cancer cells

Formulation and synthesis of the PL-loaded PLGA particles and TRAIL-conjugated liposomes yielded nanoscale particles, as outlined in Table 1. The PVA surfactant coating prevented aggregation of the polymer particles, yielding spherical shaped nanoparticles (Fig. 2). Aggregation was not a concern for the liposomes because of their hydrophilic surface characteristics.

PLGA particles were found to initially interact with both HCT116 and PC3 cell lines within the first two hours of incubation (Fig. 3a,d). Localization of the green dye suggested that the nanoparticles remained relatively intact. Some spreading of the dye indicated that particles had initially started to break down and release their cargo. After 4 and 24 hours of incubation (Fig. 3b,c,e,f), greater distribution of the dye throughout the cytoplasm was observed. This suggests that the particles had broken down to a greater extent and released their fluorescent cargo into the cytoplasm. Overall, the results suggest that PLGA nanoparticles are capable of delivering their cargo to HCT116 and PC3 cells within 24 hours of administration.

In vitro therapeutic efficacy of the dual nanoparticle therapy

When administered in vitro, cell survival rates were significantly lower for PC3 and HCT116 cells that received PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes compared to the cells which received PLGA nanoparticles and liposomes (Fig. 4). The decline in cell survival is indicative of the therapeutic efficacy of each agent, and demonstrates that the delivery vehicles themselves are not responsible for the decline in survival. A comparison of the dual nanoparticle delivery mechanism with the therapeutic agents in solution showed equivalent and improved efficacy against PC3 and HCT116 cells respectively (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Fig. 4). The delivery mechanism does not attenuate the activity of the therapy.

When administered individually, lower cell survival was observed after treatment with high concentrations of PL–PLGA or TRAIL–liposomes. This suggests that each treatment individually is more effective at higher concentrations. Amongst the treatment groups, PC3 cells were consistently observed to have a lower survival rate compared to HCT116 cells. The difference was more apparent at higher concentrations of the therapeutic agents. This observation was expected for cells treated with TRAIL–liposomes because PC3 is known to be more sensitive to TRAIL compared to HCT116 cells5,6.

When administered sequentially as part of a two-stage sensitization therapy, cell viability was observed to be significantly lower compared to cells treated with the respective individual agents. Use of two nanoparticles, each with different cargos, allowed for the independent administration of each therapeutic agent. Delivery of both agents using a single nanoparticle system may not have allowed for this feature. This independence allowed for a sensitization period to develop before the second stage of the therapy was administered. The decrease in survival was noted for both PC3 and HCT116 cells, each of which exhibits a different sensitivity to TRAIL. Effective treatment of HCT116 cells with TRAIL required a period of sensitization, which the dual nanoparticle approach was capable of providing.

The mechanism associated with the sensitization process was shown to be increased death receptor expression after treatment with PL–PLGA (Supplementary Fig. 3). The observed results suggest that PL and PL–PLGA nanoparticles are capable of sensitizing PC3 and HCT116 cells by increasing DR5 expression. TRAIL is known to initiate extrinsic apoptosis in cancer cells through interactions with DR4 and DR5 on the cell surface1–4. The observed up regulation of DR5 expression is consistent with what has been previously demonstrated utilizing a combination therapy of PL and TRAIL to treat metastatic cancers13. DR4 expression was not examined because PL has been found to produce significantly higher upregulation of DR5 compared to DR413.

In vivo therapeutic efficacy of the dual nanoparticle therapy

The observation of a higher number of apoptotic cells is consistent with the observed in vitro results that demonstrate an increased therapeutic efficacy when utilizing the two-stage nanoparticle therapy compared to each individual nanoparticle stage alone (Fig. 5). The dual nanoparticle delivery system provided a level of flexibility when administering the two stages of the therapy, allowing for an opportunity for sensitization of the tumor cells prior to administering the second component of the therapy.

From the observed results, the presence of a greater number of apoptotic cells indicates a lower survival rate for tumor cells treated with both stages of the dual nanoparticle therapy as outlined earlier. It is recognized that the intratumoral administration of the therapy presents a limitation because insight is not gained into the systemic effectiveness of the dual nanoparticle therapy. Our intent with using intratumoral injections was to be able to examine the definitive therapeutic efficacy of the treatment, without confounding influences from the pharmacokinetic factors that systemic administration presents. The use of intratumoral injections has been evaluated both pre-clinically and clinically over the past decade22–26. Additionally the technique is consistent with earlier work examining PL and TRAIL13. This same work has also examined the effect of PL and TRAIL alone when administered systemically13. The systemic effectiveness of the dual nanoparticle delivery system should be explored in future work, subject to various targeting mechanisms.

METHODS

Materials

Human prostate cancer PC3 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). Human colon cancer HCT116 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Xiling Shen (Duke University). Both cell lines were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS. Six to eight-week-old male nude mice were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Mice were housed in a SPF barrier animal facility at Cornell University.

PL was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). PLGA (acid terminated; lactide:glycolide 50:50; 38,000–54,000 kDa) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA; 9,000–10,000 kDa; 80% hydrolyzed) were both used for preparation of the nanoparticles and purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Soluble recombinant human TRAIL for in vitro work was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). His-tagged TRAIL for in vivo work was produced and purified as previously described13. TRAUT reagent used for conjugation of TRAIL to liposomes was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). Materials used to produce liposomes included Egg L-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (Egg PC), DSPE-mPEG, Maleimide-DSPE-mPEG, and cholesterol, all purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL).

Preparation of PLGA nanoparticles

Empty, PL-loaded, and dye-loaded PLGA nanoparticles were prepared using a modified oil-in-water (o/w) single emulsion process15. 25 mg of PLGA (38,000–54,000 kDa) and 2.5 mg of PL were co-dissolved in 0.5 mL of dichloromethane. The solution was sonicated at room temperature (RT) for 30 seconds using a Sonic Dismembrator Model 100 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The organic solution was added dropwise to a 1 mL aqueous solution of 2.5% PVA while vortexing. The resulting oil-water emulsion was sonicated for 30 seconds while being cooled on ice. This emulsion was then added dropwise to a magnetically stirred 1 mL aqueous solution of 0.3% PVA in an open beaker. The mixture was stirred for 2 hours at room temperature to allow for the gradual evaporation of the dichloromethane. The particle suspension was collected and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 minutes. The particles were washed with 1 mL of deionized water three times, and then suspended in 1 mL of PBS for use. Nanoparticles were freshly prepared each time they were used. Methods used for characterization and quantification of drug loading for the PLGA nanoparticles are explained in Supplementary Information S1.

Preparation of TRAIL-conjugated liposomes

A starting lipid solution of 2.04 mg of Egg PC, 0.5 mg of Cholesterol, 0.181 mg of DSPE-mPEG-2000, and 0.19 mg of Maleimide-DSPE-mPEG was prepared in chloroform. The solution was vacuum dried overnight at RT. The lipid pellet was suspended in 750 µL of liposome buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.15. The solution was snap frozen for 1 minute in an alcohol dry ice bath and then thawed for 2 minutes at 60°C. The freeze-and-thaw cycles were repeated for a total of four times. The solution was sonicated for 30 seconds between the third and fourth cycles. The lipid solution was warmed to 65°C and processed through a mini extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) maintained at 65°C. The lipid solution was sequentially passed through 0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 µm Whatman polycarbonate membrane filters (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), at a frequency of 11 cycles for each filter. The resulting liposome solution was incubated with 500 µg of thiolated TRAIL overnight at 4°C. The thiolation process is described in Supplementary Information S1. The solution was then incubated with 1 mM Beta-mercaptoethanol for 1 hour at room temperature to quench free maleimide groups on the liposomes. Liposomes were separated from unbound TRAIL via ultra-centrifugation across a sucrose gradient (5%, 30%, and 40%). The process was run for 2–3 hours at 72,737 × g using a Beckman SW 40Tirotor. The liposomes were collected from the 5–30% interface, washed with TBS buffer, and ultra-centrifuged at the same speed for an additional 1–2 hours. The pellet was re-suspended in 150 µL of 1 × TBS and passed through a 40 K Zebra Spin Desalting Column (Thermo Scientific) to change to the original liposome buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.15. Liposomes were stored rotating at 4°C prior to use3. Characterization and quantification of TRAIL loading for the liposomes are explained in Supplementary Information S1.

Cellular interactions with PLGA nanoparticles

Nanoparticle interactions with cancer cells were observed using confocal microscopy. HCT116 colon cancer cells and PC3 prostate cancer cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well in a four-well tissue culture slide (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA). The cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Cells were treated with 625 ng of PLGA nanoparticles containing Coumarin 6 dye (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and were incubated for an additional 2, 4, or 24 hours. Cells were stained with DRAQ5 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) nuclear staining dye after incubation with the particles. Nanoparticle interactions were observed using a Zeiss Confocal Microscope (Zeiss, Peabody, MA).

PL, TRAIL vs. PL–PLGA, TRAIL–liposomes in vitro efficacy

HCT116 and PC3 cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a density of 10–20,000 cells/well and incubated for 24 hours. HCT116 and PC3 cells were then treated with either PLGA, PL (15 µM), or PL–PLGA (15 µM final concentration) in the first stage of treatment. After incubating with stage 1 treatments for 24 hours at 37°C, stage 2 of the trial was administered. Both cell lines received BSA–liposomes, TRAIL (10 ng/mL and 100 ng/mL), or TRAIL–liposomes (10 ng/mL and 100 ng/mL of TRAIL). Cells were treated with the second stage of the therapy for 24 hours and cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay. Concentrations used for in vitro studies were selected based on our previous work with the PL and TRAIL combination therapy13. For cells receiving PL–PLGA and/or TRAIL–liposomes, different dosages were applied by varying the quantity of particles and/or liposomes administered. Drug loading for the PL–PLGA and TRAIL–liposomes was determined using methods outlined in Supplementary Information S1.

Evaluation of the mechanism of action for the sensitizing agent

Western blotting was used to examine the mechanism of PL27. After being treated with PLGA, PL (15 µM), or PL–PLGA (15 µM) as previously described, cell lysates were collected. A 10% SDS-PAGE gel was used to separate out the lysates, while membranes were treated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted to a 1:1000 ratio. A chemiluminescent HRP substrate was applied to detect immobilized proteins (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Measuring in vitro cell survival

Cell survival was assayed by measuring mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity using MTT as the substrate (AMRESCO, Solon, OH). After drug treatment, cells were incubated with a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL of MTT for 1 hour at 37°C. The purple MTT product was solubilized by DMSO and measured at 570 nm using a BioTek plate reader (Winooski, VT). Higher absorbances indicated higher rates of cell survival. The percent survival was calculated by forming the ratio of the absorbance of each experimental group divided by the absorbance of the control group.

Animal studies to test in vivo therapeutic effectiveness

All mice were handled according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in compliance with UK-based guidelines. All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cornell University (Protocol No. 2011-0051). On day 0, NSG mice were injected subcutaneously with 100 µL of sterile PBS containing 1 × 106 HCT116 cells. Each mouse received two injections, one on each side of the dorsal plane. Tumors were allowed to grow over several weeks, to the point where a palpable mass was observed. Two cycles of treatment were administered, with 12 hours between each stage. Stage 1 of the cycle consisted of PL–PLGA nanoparticles (2.4 mg/kg) for experimental groups and PLGA nanoparticles (2.4 mg/kg) for control groups. Stage 2 of the cycle consisted of TRAIL–liposomes (2 mg/kg) for experimental groups and an equivalent volume of liposome buffer for control groups. Each stage was injected intratumorally and alternated between stage 1 and stage 2. Different dosages were administered by varying the mass of particles and/or liposomes injected. Drug loading for the PL–PLGA nanoparticles and TRAIL–liposomes was determined using methods outlined in Supplementary Information S1. Cell and therapeutic concentrations were chosen based on our previous work with the PL and TRAIL combination therapy13. Mice were euthanized and tumors were surgically removed 24 hours after the final injection of the second cycle (Fig. 5a).

Immunohistochemistry and digital detection of apoptotic signals

Sections of 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor slides were stained with anti-human caspase-3 rabbit polyclonal antibody or rabbit IgG control. An ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and DAB kit (Vector Laboratories) was used to develop the signals from antibody staining. Slides were counterstained by hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories). Glass slides were scanned with an Aperio ScanScope scanner (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Lincolnshire, IL) and were analyzed with the automated image analysis algorithm Aperio Positive Pixel Count (Leica Microsystems, Inc.) using the default set of parameters. Within each cross-section, tumor cells were distinguished by their higher nucleus to cytoplasm ratio (N/C ratio), which is observed in cancer cells13. The ratio of strongly positive signals to the total intensity of the detected signals was determined.

Statistical analysis

Presented graphical data depict the average cell survival rates with errors bars reaching a standard deviation above the mean. Two sample t-tests were performed to determine if statistically significant differences existed between treatment groups for in vitro cell survival and between the results of the image analysis of the collected tumor cross-sections. All statistical analyses were performed using R analysis soft ware (Bell Labs, Murray Hill, NJ) for Windows (Microsoft, Redmond, VA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine M. Peterson and David E. Mooneyhan for their assistance with animal experiments through the Cornell Center for Animal Resources and Education (CARE). This work was supported by an NIH/NCI grant (U54CA143876, M.R.K). This work made use of the Cornell Center for Materials Research Shared Facilities which are supported through the NSF MRSEC program (DMR-1120296). This work also made use of the Nanobiotechnology Center shared research facilities at Cornell. Confocal images were collected using the Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope at the Cornell University Biotechnology Resource Center (BRC) Imaging Facility, which is supported by NIH grant no. S10RR025502.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The project was conceived by C.C.S. and J.L. Experiments were designed by C.C.S., J.L., and M.R.K. Experiments were performed and data were analyzed by C.C.S., J.L., S.R., and Q.W. The results were discussed by C.C.S., J.L., S.R., Q.W., and M.R.K. The manuscript was written by C.C.S. and reviewed by C.C.S., J.L., and M.R.K.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang S, El-Deiry W. TRAIL and apoptosis induction by TNF-family death receptors. Oncogene. 2003;22:8628–8633. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang S. The promise of cancer therapeutics targeting the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand and TRAIL receptor pathway. Oncogene. 2008;27:6207–6215. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell M, Wayne E, Rana K, Schaffer C, King M. TRAIL-coated leukocytes that kill cancer cells in the circulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:930–935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316312111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Ai Y, Wang L, Bu P, Sharkey C, Wu Q, Wun B, Roy S, Shen X, King M. Targeted drug delivery to circulating tumor cells via platelet membrane-functionalized particles. Biomaterials. 2015;76:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimberg LY, et al. On the TRAIL to successful cancer therapy? Predicting and counteracting resistance against TRAIL-based therapeutics. Oncogene. 2013;32:1341–1350. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yodkeeree S, Sung B, Limtrakul P, Aggarwal B. Zerumbone enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the induction of death receptors in human colon cancer cells: Evidence for an essential role of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6581–6589. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolfi C, Pallone F, Monteleone G. Molecular targets of TRAIL-sensitizing agents in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:7886–7901. doi: 10.3390/ijms13077886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorsey J, et al. Tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and paclitaxel have cooperative in vivo effects against glioblastoma multiforme cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3285–3289. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter T, Manimala N, Luddy K, Catlin T, Antonia S. Paclitaxel and TRAIL synergize to kill paclitaxel-resistant small cell lung cancer cells through a caspase-independent mechanism mediated through AIF. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:3193–3204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Wilt LH, Kroon J, Jansen G, de Jong S, Peters GJ, Kruyt FA. Bortezomib and TRAIL: A perfect match for apoptotic elimination of tumour cells? Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013;85:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikrad M, et al. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib sensitizes cells to killing by death receptor ligand TRAIL via BH3-only proteins Bik and Bim. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005;4:443–449. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanker A, et al. Treating metastatic solid tumors with bortezomib and a tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor agonist antibody. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008;100:649–662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Sharkey C, King M. Piperlongumine and immune cytokine TRAIL synergize to promote tumor death. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9987. doi: 10.1038/srep09987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raj L, et al. Selective killing of cancer cells by a small molecule targeting the stress response to ROS. Nature. 2011;475:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature10167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Liu J, Jiang Z, Zhang S, Saltzman W. Poly(ω-pentadecalactone-co-butylene-co-succinate) nanoparticles as biodegradable carriers for camptothecin delivery. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5707–5719. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng C, Saltzman W. Enhanced siRNA delivery into cells by exploiting the synergy between targeting ligands and cell-penetrating peptides. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6194–6203. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J, et al. PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles for the improved delivery of doxorubicin. Nanomedicine. 2009;5:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danhier F, et al. Paclitaxel-loaded PEGylated PLGA-based nanoparticles: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Control. Rel. 2009;133:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang HH, et al. PEGylated TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) for effective tumor combination therapy. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8529–8537. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parodi A, et al. Synthetic nanoparticles functionalized with biomimetic leukocyte membranes possess cell-like functions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013;8:61–68. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng M, et al. PLGA–Lecithin–PEG core-shell nanoparticles for cancer targeted therapy. Nano LIFE. 2012;2:1250002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sersa G, et al. Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin: Clinical experience in malignant melanoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:863–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gochi A, et al. The prognostic advantage of preoperative intratumoral injection of OK-432 for gastric cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;84:443–451. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie H, et al. Effect of intratumoral administration on biodistribution of Cu-64-labeled nanoshells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012;7:2227–2238. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S30699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lammers T, et al. Effect of intratumoral injection on the biodistribution and the therapeutic potential of HPMA copolymer-based drug delivery systems. Neoplasia. 2006;8:788–795. doi: 10.1593/neo.06436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han HD, et al. Enhanced localization of anticancer drug in tumor tissue using polyethylenimine-conjugated cationic liposomes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014;9:209. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, et al. Human fucosyltransferase 6 enables prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Br. J. Cancer. 2013;109:3014–3022. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meure L, Foster N, Dehghani F. Conventional and dense gas techniques for the production of liposomes: A review. Am. Assoc. Pharm. Sci. 2008;9:798–809. doi: 10.1208/s12249-008-9097-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.