Abstract

The Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study is a randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate if a lifestyle intervention targeting fat intake reduction influences breast cancer recurrence in women with early stage, resected disease receiving conventional cancer management. This report details the concept, content, and implementation of the low-fat eating plan used in the dietary intervention group of this trial. Intervention group participants were given a daily fat gram goal. The intervention was delivered by centrally trained, registered dietitians who applied behavioral, cognitive, and motivational counseling techniques. The low-fat eating plan was implemented in an intensive phase with eight biweekly (up to Month 4), individual counseling sessions followed by a maintenance phase (Month 5 up to and including Year 5) with registered dietitian visits every 3 months and optional monthly group sessions. Self-monitoring (daily fat gram counting and recording), goal setting, and motivational interviewing strategies were key components. Dietary fat intake was equivalent at baseline and consistently lower in the intervention compared with the control group at all time points (percent eneregy from fat at 60 months 23.2% ± 8.4% vs 31.2% ± 8.9%, respectively, P< 0.0001) and was associated with mean 6.1 lb mean weight difference between groups (P = 0.005) at 5 years (baseline and 5 years, respectively: control 160.0 ± 35.0 and 161.7 ± 32.8 lb; intervention 160.2 ± 35.1 and 155.6 ± 32.1 lb). Together with previously reported efficacy results, this information suggests that a lifestyle intervention that reduces dietary fat intake and is associated with modest weight loss may favorably influence breast cancer recurrence. The Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study low-fat eating plan can serve as a model for implementing such a long-term dietary intervention in clinical practice.

The relationship between dietary fat intake and breast cancer outcome has been examined in a total of 14 observational studies with seven studies demonstrating a significant association between lower fat intake and lower recurrence risk (1,2). The Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) is a multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial to directly address this issue, testing the effect of a dietary intervention designed to reduce fat intake on breast cancer recurrence in women receiving conventional cancer management for early stage disease. The WINS intervention significantly reduced dietary fat intake, associated with moderate weight loss, and interim efficacy results suggested clinical outcomes were improved (3). Details of the WINS dietary intervention, including its conceptual basis, content, implementation processes, and its influence on dietary and anthropometric endpoints are reported to inform use in clinical practice.

METHODS

The goal of the dietary intervention (the WINS low-fat eating plan) was to reduce the percentage of total energy intake from fat down to 15% while maintaining nutritional adequacy. This goal was based on findings from feasibility trials indicating that a 15% goal would result in a sustained reduction of fat intake of about 20% of energy intake (4,5). Randomization for this trial was 40:60 for the low-fat intervention vs control group to save resources at minimal loss in statistical power. Control group subjects were provided a US Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines pamphlet at baseline and educational handouts to address any suboptimal nutrient intakes identified from annual dietary recalls.

WINS Study Population

The WINS protocol details have been previously described (3). Briefly, participants had histologically confirmed, resected invasive breast cancer, were between 48 and 79 years of age, and were within 365 days of cancer surgery. Acceptable adjuvant systemic cancer therapy was required and dietary intake had to be >20% of energy from fat at baseline. For eligibility, fat intake was estimated from three unannounced telephone 24-hour recalls (including one weekend day) over 2 weeks. Acceptable adjuvant therapy included radiation, select chemotherapies (required for hormone receptor negative cancers), and tamoxifen for receptor positive cancers. The institutional review board of each participating institution approved the study and all participants gave written informed consent. A CONSORT trial flow diagram has been previously published (3).

Study Organization: Standardizing Treatment Delivery

To address uniformity of practice and quality control, session-by-session protocols described topics and information to be addressed. Study registered dietitians (RDs) were trained centrally on diet intervention, behavior change strategies, and anthropometric data collection. Training continued with monthly conference calls and annual workshops incorporating training on motivational interviewing. Ongoing trial management was facilitated by site visits from the WINS Nutrition Intervention Coordinating Unit. Whenever possible, the same RD counseled the same participant to promote a provider/participant relationship and provide continuity of the intervention.

Dietary Intake Assessment

Adherence to the low-fat eating plan was monitored by unannounced 24-hour telephone recalls (6,7). Centrally trained interviewers blinded to randomization called participants at baseline, 3 months, and annually from central locations with information entered into the Nutrition Data System for Research interactive software. Annual dietary intakes were estimated from two nonconsecutive telephone recalls (one on a weekend day) (6).

Intervention Schedule During Intensive Intervention and Maintenance Phases

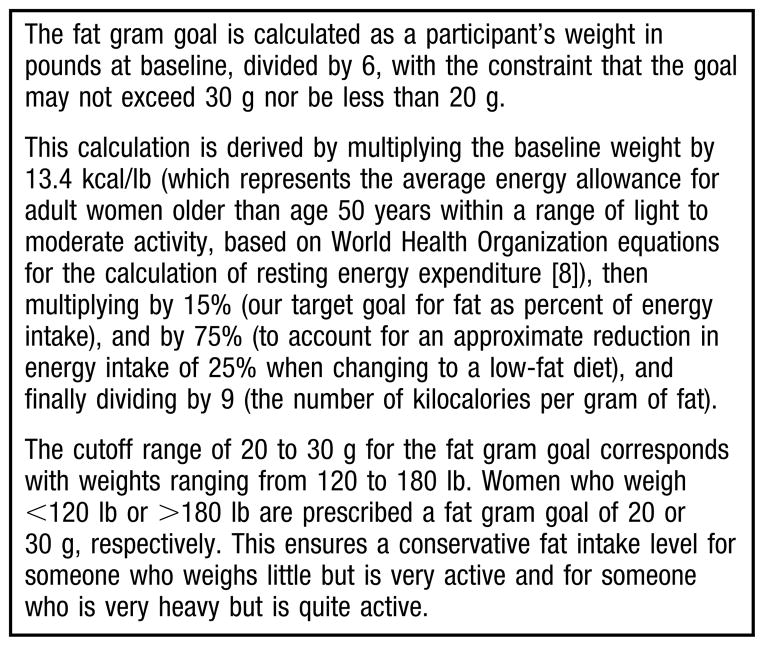

At study entry, intervention group participants were given a daily fat gram goal calculated based on body weight in pounds divided by six, with all goals set between 20 and 30 grams (following the procedure described in Figure 1) (8). For example, if a woman weighed 180 lb her daily goal was no more than 30 g fat. Participants were also advised not to fall too far below their goal to support adequate micronutrient and essential fatty acid intake.

Figure 1.

Calculation of Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) dietary intervention participants’ daily fat gram goals to facilitate consumption of the WINS low-fat diet that is up to 15% energy as fat.

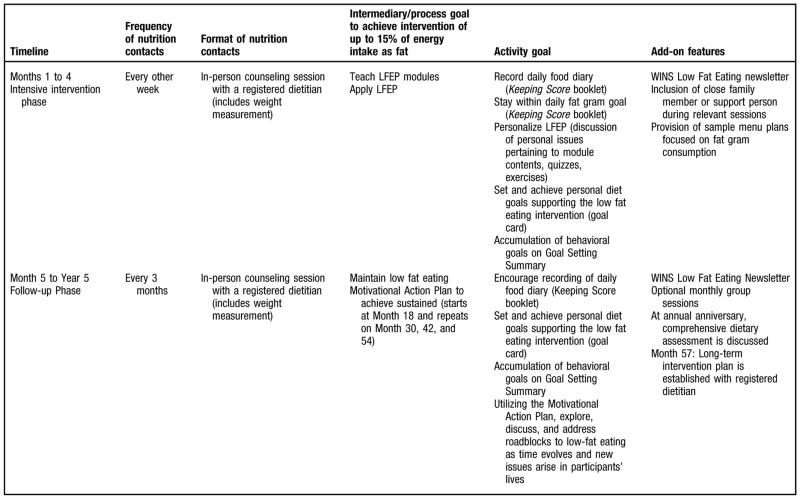

The low-fat eating plan was initiated with an initial intensive intervention phase followed by a maintenance phase. During the intensive phase, participants met individually with the RD every 2 weeks for eight sessions lasting about 1 hour each. In the maintenance phase, subsequent RD visits were held quarterly, and optional monthly group sessions were offered. After 5 years, participants’ clinic visits were reduced to biannual with biannual phone contacts between visits.

The Five Low-Fat Eating Plan Principles: Selecting and Preparing Foods

The low-fat eating plan was based primarily on the social cognitive theory of behavior change (9) and included goal setting, self-monitoring (fat gram counting and recording), modeling, and social support. Relapse prevention and management techniques (10) were used to maintain adherence. To promote tailoring of counseling, the Transtheoretical Model of Change (11) was combined with motivational interviewing techniques (12). This included the development and use of the Motivational Action Plan as a data collection instrument and counseling tool designed to maintain or improve long-term adherence to the low-fat diet (13).

Reducing dietary fat intake involved three general strategies: substitution (of low-fat foods and cooking methods for those high in fat), elimination (of high-fat foods), and reduction (in portion sizes of high-fat foods) based on the five low-fat eating plan principles: reduce the amount of oils and high-fat spreads, dressings, and sauces; choose low-fat dairy products; choose low-fat fish, poultry, meat, and egg whites or egg substitutes and eat smaller portions of these foods; eat more fruits, vegetables, legumes, and grain products; and substitute low-fat desserts, snacks, and beverages for high-fat items (14,15).

Instructional materials for the application of the low-fat eating plan were developed to address common barriers to successful behavior change, including:

Appetite

The difference between appetite and physiological hunger and identification and management of appetite triggers and hunger.

Environmental Cues

The influence of external cues for eating, such as sensory triggers (sight and smell of food), availability of food, and time of day.

High-Risk Situations

Such as holidays, restaurant dining, special occasions, and emotional cues.

Negative Thinking

Self-defeating thoughts.

Social Eating

Strategies to manage challenging social situations.

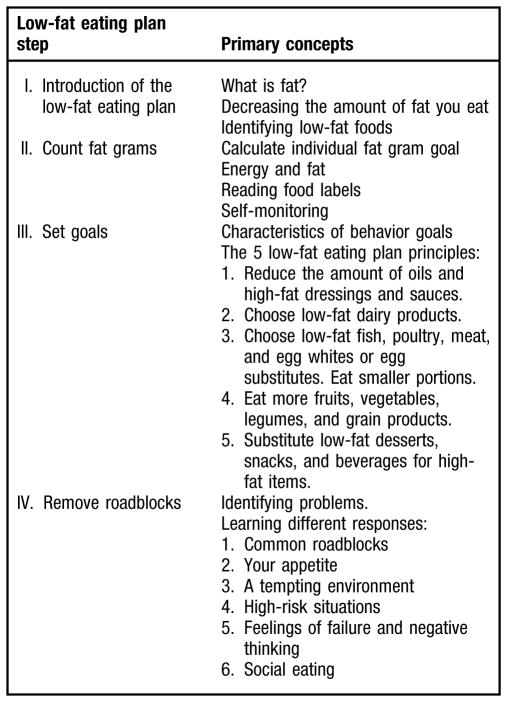

Implementing the Low-Fat Eating Plan

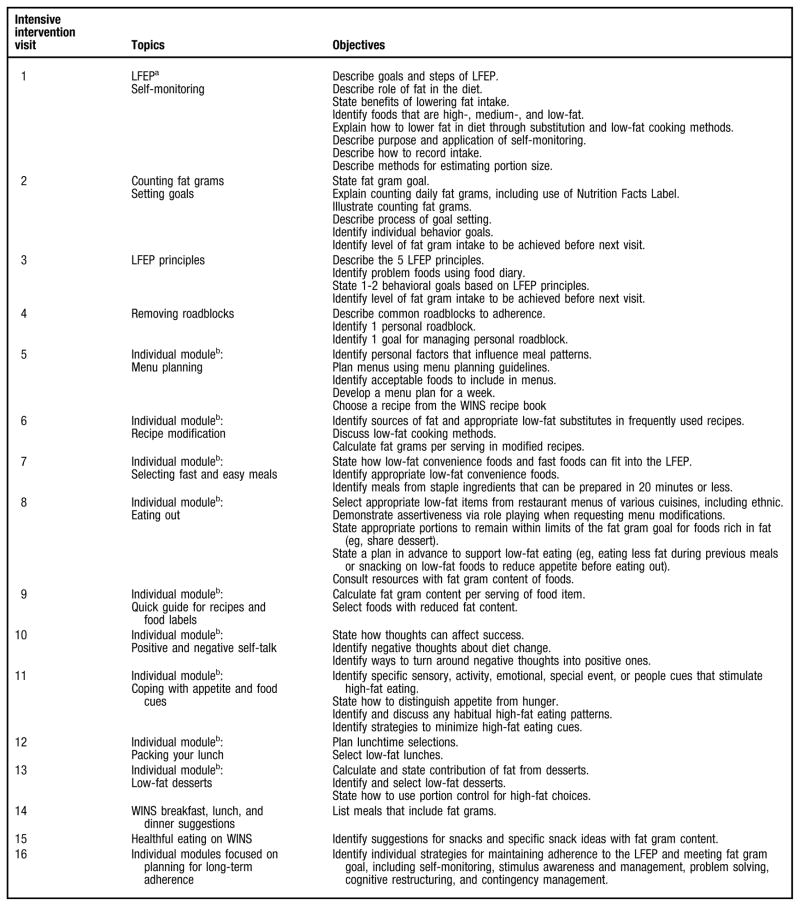

The WINS low-fat eating plan incorporates four discrete behavior steps: learning the low-fat eating plan, counting fat grams, setting goals, and removing roadblocks (see Figure 2). These four steps encompass the five basic principles for selecting and preparing low-fat foods. The topics and objectives of the intensive intervention visits are outlined in Figure 3. Each visit introduced new information and identified relevant behavior goals designed to reduce fat intake. Depending on individual assimilation, the four behavioral steps were commonly completed in four, three, or even two visits at the discretion of the RD. Subsequent sessions were used to identify problems and provide counseling to promote long-term adherence. Counseling sessions typically included a review of goals since the last visit, review of prior fat intake, assessment and discussion of progress and/or problem areas, and formal setting of behavioral goals for the next visit.

Figure 2.

Four steps of the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study low-fat eating plan.

Figure 3.

Topics and objectives of the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) intensive intervention visits. aLFEP = low-fat eating plan. bIndividual modules contain supplementary information for participants to promote adherence to the LFEP, and are provided based on individual needs and interests.

The calculated fat gram goal provided a daily quantitative target for their dietary fat intake reduction. Participants were instructed to keep a written record of their fat gram intake daily using a previously developed Keeping Score book and Fat Gram Counter (14). Emphasized concepts included consideration of portion size, use of the Nutrition Facts Label, and tips for estimation of fat grams in mixed dishes and for food eaten away from home.

Setting individualized goals was an integral component of the low-fat eating plan. In the goal setting process workable solutions to problems encountered in lowering fat intake were developed. Each goal was stated in behavioral terms and included a concrete and verifiable outcome. A goal could be “to include cheese with less than 3 g fat per slice in my lunch sandwich instead of the cheese I now use for the next month.” Goals were recorded on a personal Goal Card, and study RDs documented their status on a Goal Setting Summary document. This document was reviewed centrally, and follow-up with the RD at their clinical center was provided to address adherence issues. An overview of the WINS low-fat eating plan is outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Overview of the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) low-fat eating plan (LFEP) lifestyle intervention.

Counseling on the Low-Fat Eating Plan

The crux of the low-fat eating plan was individualized counseling to initially educate and then guide participants to long-term maintenance of a low-fat diet through awareness of eating habits and the ability to identify and manage personal barriers to low-fat eating. Counseling used the participant-centered model and incorporated motivational interviewing strategies to facilitate behavior change and maintain long-term adherence, which was facilitated by use of the Motivational Action Plan. During the last intensive intervention phase visit, participants developed a long-range plan to maintain fat intake reduction. Relapse prevention and management skills needed for management of personal barriers were discussed and incorporated into the plan, including problem-solving techniques and coping skills.

Other Adherence Strategies

Other adherence strategies used in WINS included monthly group sessions, group-specific newsletters, monthly group specific, quarterly mailings, and study-wide incentives. Group sessions were designed to provide support and modeling through group discussions, and build upon information provided in individual sessions through role-playing, demonstrations, and the sharing of practical experiences.

Statistical Analysis

The nutrient intake and anthropometrics presentations are reconfigurations of previously reported results (3). Differences in baseline variables between and within groups were analyzed using t tests or paired t tests. The t tests were performed to compare differences in the nutrient intakes and anthropometric variables, and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are reported.

RESULTS

A total of 2,437 women were randomly assigned, 975 to the dietary intervention and 1,462 to the control group. Dietary data is available for at least three of six time periods after baseline on 80% of participants. In the control group, 66 were lost to follow-up and 106 discontinued study participation. In the intervention group, 45 were lost to follow-up and 170 discontinued the dietary intervention. Only six women cited that they “did not like the low-fat eating plan” as the reason.

Dietary fat intakes were closely comparable at baseline (29.6% ± 6.7% and 29.6% ± 7.1% of energy intake from fat for intervention and controls groups, respectively). After 1 year, dietary fat intake was reduced to a greater degree in the intervention compared to the control group, and the reduction was maintained throughout the study. At 5 years, the daily fat gram intake was 53.9 ± 26.7 g in the control group and 34.9 ± 18.4 g in the intervention group (P < 0.0001), representing 31.4% ± 23.2% and 23.2% ± 8.4% of energy as fat in the control and intervention groups, respectively (see the Table). At baseline body weight was closely comparable in the randomization groups (160.2 ± 35.1 lb and 160.0 ± 35.0 lb in intervention and control groups, respectively). After 1 year, body weight was lower in the intervention group and a difference was maintained between groups throughout the study. At 5 years, control group women weighed an average of 161.7 ± 32.8 lb compared to 155.6 ± 32.1 lb for intervention group women (P = 0.005).

Table.

Percent energy intake from fat by Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) dietary intervention group compared to the WINS control group at baseline and annually thereafter to 6 yearsa

| Energy Intake from Fat (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-Up Interval (mo)

|

|||||||

| Group | Baseline | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | 72 |

| ←------------mean ± standard deviation-----------→ | |||||||

| Dietary intervention | 29.637.1 | 20.337.8 | 21.238.2 | 21.738.4 | 22.638.5 | 23.238.4 | 23.039.2 |

| Control | 29.636.7 | 29.238.2 | 30.138.3 | 30.738.7 | 30.538.7 | 31.238.9 | 31.438.2 |

Information on dietary intake was available for 975 and 1,461 of women in the dietary intervention group and the control group, respectively, at baseline; for 840 and 1,328 women, respectively, at Year 1; for 654 and 1,077 women, respectively, at Year 3; and for 380 and 648 women, respectively, at Year 5.

DISCUSSION

The WINS low-fat eating plan resulted in significant and sustained reductions in both fat intake as well as body weight. These results, together with outcomes from other full scale trials (16–18) indicate that demanding lifestyle interventions involving significant modification of dietary intake can be successfully implemented over extended periods of time (16–19). In an interim efficacy report from the WINS trial, breast cancer recurrence was less frequent in women randomized to the intervention group and subgroup analyses suggested a larger effect on hormone receptor negative breast cancers (3). Analyses relating dietary adherence to breast cancer outcome await completion of ongoing nonintervention follow-up.

Successful lowering of fat intake by WINS participants was characterized by several types of dietary changes. Those classified as “strictly adherent” who met their fat gram goal not only decreased their intake of discretionary fat from oils, sweets and fat, but also reduced their intake of sweet breads, pastries, and desserts; cheese; poultry, beef, pork, and lamb; nuts and seeds; and eggs to a greater degree than did those who were not strictly adherent (15). As total fat intake was reduced in WINS intervention participants, daily intake of saturated fats were reduced from 19 to 10 g, monosaturated fats from 22 to 12 g, and polyunsaturated fats from 12 to 6 g and a modest increase in fiber from 18 to 20 g was seen. These differences all were statistically significant compared to controls and were maintained through 72 months (3).

Few other randomized trials have evaluated lifestyle intervention on breast cancer outcomes. The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) trial evaluated a dietary intervention targeting vegetable, fruit, and fiber increase as well as fat intake reduction in women with early stage, resected breast cancer. Although increases in vegetable, fruit, and fiber intake were achieved, the WHEL program had no effect on breast cancer recurrence (20). The WHEL and WINS trials differ in several respects, most notably, the modest reduction in fat intake and the absence of weight loss in the WHEL trial (21). Specifically, in WHEL, the percent of energy from fat was 28.5% at baseline, 27.1% at 48 months, and 28.9% at 72 months—substantially higher than that seen in the WINS trial at the same benchmarks (see the Table).

The Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification (WHI-DM) trial, a primary prevention study of 48,386 postmenopausal women, evaluated the influence of a low-fat dietary pattern on primary breast cancer prevention (22). Dietary intervention was initiated with 16 group sessions and individual RD counseling was not provided. While 9% fewer breast cancers were seen in the intervention group, the difference was not significant (P = 0.07). The reduction in fat intake in percent of energy comparing intervention to control group was similar in the WHI-DM and WINS trials. However, higher baseline fat intakes in WHI DM participants led to higher post intervention levels, especially because WHI-DM dietary adherence faltered over time.

WINS used the multiple-pass 24-hour recall method to assess fat intake annually, an approach that has received validation in several settings (23,24). WINS procedures were designed to minimize reporting bias by blinding WINS clinic RDs to actual food intake reported by participants and using independent, off-site interviews to perform recalls (7). However, errors in measurement of dietary intake can be problematic with any approach especially regarding underreporting. Nonetheless, the decrease in dietary fat intake reported by the intervention group was supported by the significantly lower and sustained differences in mean body weight seen compared with the control group.

During the 5.2-year study period, a total of 22% of intervention group participants were either lost to follow-up or discontinued the dietary intervention, representing a study limitation. However, adherence to prescribed treatment, even within the scope of established breast cancer therapy, is problematic. For example, when evaluated in clinical practice settings, adjuvant tamoxifen use was prematurely discontinued by 30% to 50% of patients before completion of a scheduled 5-year course (25).

CONCLUSIONS

The WINS low-fat eating plan is a comprehensive, theory-based lifestyle intervention that resulted in reduced fat intake, modest weight loss and a suggested favorable affect on breast cancer recurrence especially in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor negative disease. A description of the methodology used in implementing this low-fat eating plan can serve as a model for its use by RDs in clinical practice.

Because both reduced fat intake and modest weight loss were seen in the WINS dietary intervention group, the relative contribution of each to breast cancer clinical outcome cannot be determined. Therefore, replication of this intervention in practice should target both fat intake and sustained, modest weight loss (3,26,27).

The intensive intervention phase was implemented in eight biweekly visits. The 16 topics presented during these eight visits were provided at a pace dependent on the RD’s assessment of the participant’s grasp of the presented information. The self-monitoring of fat intake with daily use of the Keeping Score book represents a critically important early behavior that rapidly increased knowledge regarding the fat content of food choices. It is our impression dealing with such a motivated population that the intervention phase could be completed with fewer visits perhaps four or less. We can provide no information on the efficacy of a less intensive program because only one intervention strategy was employed in WINS. However, results from other successful lifestyle programs suggest that, ongoing multiyear contacts and development of supportive partnering relationships between participants and the intervening RDs are needed to prevent dietary relapses (27,28). The 3-month schedule of RD contacts was sufficient and likely necessary to maintain long-term adherence.

In the WINS trial dietary intakes for clinical trial purposes were assessed using 24-hour telephone recalls. However, for the purposes of monitoring adherence in clinical practice, body weight measurements and reviews of keeping score books should be sufficient to guide RD counseling efforts.

Finally, in clinical settings, reimbursement for dietary services in cancer populations may be limited. Formal cost and time assessment analyses are beyond the scope of the current report (29). However, in relative terms the total incurred cost (eg, RD time and printed support materials) would be less than those involved in just one course (usually 2 to 3 weeks) of chemotherapy with current adjuvant regimens (30–32) or approximately 6 months of a scheduled 5-year course of aromatase inhibitor use (33).

The information in this report presents a strategy for implementing the WINS low-fat eating plan in clinical practice. If a breast cancer patient in consultation with an RD asks, “What can I do to prevent breast cancer from recurring?” the WINS low-fat eating plan may be one answer.

Acknowledgments

This study was primarily funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Health and Human Services. Funding for supplemental projects was provided by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the American Institute for Cancer Research. This study was supported as an investigator-initiated RO-1 grant. The WINS investigators (with input from the independent WINS External Advisory Committee) were solely responsible for the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript, and decision to submit for publication.

The authors thank the following RDs who delivered the WINS dietary intervention: W. Hirsch, M. Horan, and D. Moran (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center); M. Lubin, E. Falk, V. Fortunato, F. Ebel, C. Papoutsakis, N. Darak Feldman, and S. Anikstein (Institute for Cancer Prevention/American Health Foundation); J. Ferrares, M. Beddome, and V. Marsoobian (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center); J. Reddan, A. Snyder, and S. Marshall (Park Nicollet Institute for Oncology Research); N. Adamowicz, E. Nardi, and T. Crane (University of Arizona); P. Jensen and J. Galicinao (University of Hawaii); R. Beller (John Wayne Cancer Institute); J. Schenk (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center); M. Sokil (Kaiser Permanente Medical Group, Oakland); K. Schwab and K. Willeford (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland); C. Rheingruber (Evanston Hospital, Kellogg Cancer Care Center); R. Zinaman (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center); K. Radokovich (Wayne State University); C. Coy and H. Backer (University of California Irvine Cancer Center); L. Shepard (Bennett Cancer Center); M. Bellman and M. Chrabaszewski (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center); J. Pleuss (Medical College of Wisconsin); D. Strong and M. Ng (North Shore University Hospital); C. Richardson (Duke University); M. Vides (Saint Barnabas Medical Center); A. Campa and N. Falla (University of Miami); S. Shannon and D. Wilson (Medical University of South Carolina); S. Heilman (Christus Spohn Breast Care Program); P. Gregory (Shands Cancer Center); K. Lombardi and L. Kelleher (Rhode Island Hospital); B. Whilden (Geisinger Medical Center); K. Mulligan (Ohio State University); L. Ahrens, K. Bierl, and L. Nylin (University of Iowa); L. Wolf (Good Samaritan Medical Center); S. Sloan (Lombardi Cancer Research Center), A. Maggi (Sharp Health Care); and H. Gabbert and S. Dahlk (Midwestern Regional Medical Center).

Oversight of dietary assessment was conducted by Diane Mitchell and Helen Smiciklas-Wright, Dietary Assessment Coordinating Center, Penn State University, University Park, PA.

Contributor Information

M. KATHERINE HOY, Research Manager, Produce for Better Health Foundation, Wilmington, DE; at the time of the study, she was Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) national coordinator and WINS assistant national coordinator, Institute for Cancer Prevention, formerly American Health Foundation, New York, NY.

BARBARA L. WINTERS, Research Scientist, Campbell Soup Company, Camden NJ; at the time of the study, she was WINS national coordinator, American Health Foundation, New York, NY.

ROWAN T. CHLEBOWSKI, WINS Principal Investigator, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA.

CONSTANTINA PAPOUTSAKIS, Teaching and Research Associate, Laboratory of Nutrition and Clinical Dietetics, Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Harokopio University, Athens, Greece; at the time of the study, she was WINS protocol coordinator, American Health Foundation, New York, NY.

ALICE SHAPIRO, Research Scientist, Institute at Park Nicollet Health Services, Minneapolis, MN; at the time of the study, she was principal investigator, Institute for Park Nicollet Health Services, Minneapolis, MN.

MICHELE P. LUBIN, Nutritionist, Winthrop University Hospital Department of Surgery, Mineola, NY; at the time of the study, she was WINS intervention coordinator, Institute for Cancer Prevention, formerly American Health Foundation, New York, NY.

CYNTHIA A. THOMSON, Associate Professor, University of Arizona, Arizona Cancer Center and Department of Nutritional Sciences, Tucson; at the time of the study, she was principal investigator, University of Arizona Cancer Center, Tucson.

MARY B. GROSVENOR, Adjunct Professor, Delta Montrose Technical College, Department of Nursing, Delta, CO; at the time of the study, she was WINS dietary assessment coordinator, Institute for Cancer Prevention, formerly American Health Foundation, New York, NY.

TRISHA COPELAND, Research Coordinator, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA; at the time of the study, she was national assessment operations manager, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston, MA.

ELYSE FALK, Nutritionist, Cedar Associates Eating Disorder Center, Mt Kisco, NY; at the time of the study, she was WINS protocol coordinator, Institute for Cancer Prevention, formerly American Health Foundation, New York, NY.

KRISTINA DAY, Research Nutritionist, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

GEORGE L. BLACKBURN, WINS Principal Investigator, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Chlebowski RT, Aiello E, McTiernan A. Weight loss in breast cancer patient management. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1128–1143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kushi LH, Kwan ML, Lee MM, Ambrosone CB. Lifestyle factors and survival in women with breast cancer. J Nutr. 2007;137(suppl):236S–242S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.236S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Thomson CA, Nixon DW, Shapiro A, Hoy MK, Goodman MT, Giuliano AE, Karanja N, McAndrew P, Hudis C, Butler J, Merkel D, Kristal A, Caan B, Michaelson R, Vinciguerra V, Del Prete S, Winkler M, Hall R, Simon M, Winters BL, Elashoff RM. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: Interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1767–1776. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chlebowski RT, Nixon DW, Blackburn GL, Jochimsen P, Scanlon EF, Insull W, Jr, Buzzard IM, Elashoff R, Butrum R, Wynder EL. A breast cancer Nutrition Adjuvant Study (NAS): Protocol design and initial patient adherence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1987;10:21–29. doi: 10.1007/BF01806131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Buzzard IM, Rose DP, Martino S, Khandekar JD, York RM, Jeffery RW, Elashoff RM, Wynder EL. Adherence to a dietary fat intake reduction program in postmenopausal women receiving therapy for early breast cancer. The Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:2072–2080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.11.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copeland T, Grosvenor M, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Marsoobian V, Blackburn G, Winters B. Designing a quality assurance system for dietary data in a multicenter clinical trial: Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:1186–1190. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buzzard IM, Faucett CL, Jeffery RW, McBane L, McGovern P, Baxter JS, Shapiro AC, Blackburn GL, Chlebowski RT, Elashoff RM, Wynder EL. Monitoring dietary change in a low-fat diet intervention study: Advantages of using 24-hour dietary recalls vs food records. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:574–579. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Recommended Dietary Allowances. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1989. p. 33. 10th revision. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Principles of Behavior Modification. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Institute Tech Report No. 78–07. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1978. Determinants of Relapse: Implications for the Maintenance of Behavior Change. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing, Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoy MK, Lubin MP, Grosvenor MB, Winters BL, Liu W, Wong WK. Development and use of a Motivational Action Plan for dietary behavior change using a patient-centered counseling approach. Top Clin Nutr. 2005;20:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buzzard IM, Asp EH, Chlebowski RT, Boyar AP, Jeffery RW, Nixon DW, Blackburn GL, Jochimsen PR, Scanlon EF, Insull W, Jr, Elashoff RM, Butrum R, Wynder EL. Diet intervention methods to reduce fat intake: Nutrient and food group composition of self-selected low-fat diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 1990;90:42–50. 53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winters BL, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Grosvenor MB, Liu W, Blackburn GL. Dietary patterns in women treated for breast cancer who successfully reduce fat intake: The Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delahanty L, Simkins SW, Camelon K. Expanded role of the dietitian in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial: Implications for clinical practice. The DCCT Research Group. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93:758–764. 767. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91748-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillis BP, Caggiula AW, Chiavacci AT, Coyne T, Doroshenko L, Milas NC, Nowalk MP, Scherch LK. Nutrition intervention program of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study: A self-management approach. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(95)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiebaut AC, Schatzkin A, Ballard-Barbash R, Kipnis V. Dietary fat and breast cancer: Contributions from a survival trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1753–1755. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Greenberg ER, Flatt SW, Rock CL, Kealey S, Al-Delaimy WK, Bardwell WA, Carlson RW, Emond JA, Faerber S, Gold EB, Hajek RA, Hollenbach K, Jones LA, Karanja N, Madlensky L, Marshall J, Newman VA, Ritenbaugh C, Thomson CA, Wasserman L, Stefanick ML. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298:289–298. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL. Diet and breast cancer recurrence. JAMA. 2007;298:2135–2136. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2135-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prentice RL, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, Patterson R, Kuller LH, Ockene JK, Margolis KL, Limacher MC, Manson JE, Parker LM, Paskett E, Phillips L, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto GE, Shikany JM, Stefanick ML, Thomson CA, Van Horn L, Vitolins MZ, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace RB, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Whitlock E, Yano K, Adams-Campbell L, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Beresford SA, Black HR, Brunner RL, Brzyski RG, Ford L, Gass M, Hays J, Heber D, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Hsia J, Hubbell FA, Jackson RD, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, LaCroix AZ, Lane DS, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Henderson MM. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of invasive breast cancer: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:629–642. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conway JM, Ingwersen LA, Vinyard BT, Moshfegh AJ. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanton CA, Moshfegh AJ, Baer DJ, Kretsch MJ. The USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method accurately estimates group total energy and nutrient intake. J Nutr. 2006;136:2594–2599. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chlebowski RT, Geller ML. Adherence to breast cancer hormonal therapy. Oncology. 2007;71:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000100444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blackburn GL, Waltman BA. Obesity and insulin resistance. In: Mc-Tiernan A, editor. Cancer Prevention and Management through Exercise and Weight Control. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2005. pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, Stunkard AJ, Wilson GT, Wing RR, Hill DR. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19:5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phelan S, Wing RR. Prevalence of successful weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2430. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2430-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papoutsakis C, Winters BL, Falk E, Feldman N, Hoy K, Lubin M, Prince K, Anikstein S, Bellinger S, Nixon D. Time-cost analysis for conducting a long-term clinical nutrition intervention trial: Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) FASEB J. 2000;14:A739. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Citron ML, Berry DA, Cirrincione C, Hudis C, Winer EP, Gradishar WJ, Davidson NE, Martino S, Livingston R, Ingle JN, Perez EA, Carpenter J, Hurd D, Holland JF, Smith BL, Sartor CI, Leung EH, Abrams J, Schilsky RL, Muss HB, Norton L. Randomized trial of dose-dense vs conventionally scheduled and sequential vs concurrent combination chemotherapy as postoperative adjuvant treatment of node-positive primary breast cancer: Frst report of Intergroup Trial C9741/Cancer and Leukemia Group B Trial 9741. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1431–1439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer CE, Jr, Davidson NE, Tan-Chiu E, Martino S, Paik S, Kaufman PA, Swain SM, Pisansky TM, Fehrenbacher L, Kutteh LA, Vogel VG, Visscher DW, Yothers G, Jenkins RB, Brown AM, Dakhil SR, Mamounas EP, Lingle WL, Klein PM, Ingle JN, Wolmark N. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones S, Holmes F, O’Shaughnessy J, Blum J, Vukelaj S, McIntyre K, Pippen J, Bordelon J, Kirby R, Sandbach J, Hyman W, Khandelwal P, Negron A, Richards D, Mennel R, Boehm K, Meyer W, Asmar L, Muss H, Savin M. Extended follow-up and analysis by age of the US Oncology Adjuvant trial 9735: Docetaxel/cyclophosphamide is associated with an overall survival benefit compared to doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide and is well tolerated in women 65 or older. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. 2007:A12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baum M, Buzdar A, Cuzick J, Forbes J, Houghton J, Howell A, Sahmoud T. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination) trial efficacy and safety update analyses. Cancer. 2003;98:1802–1810. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]