Abstract

Background

Benign lichenoid keratosis (BLK, LPLK) is often misdiagnosed clinically as superficial basal-cell carcinoma (BCC), especially when occurring on the trunk. However, BCCs undergoing regression may be associated with a lichenoid interface dermatitis that may be misinterpreted as BLK in histopathologic sections.

Methods

In order to assess the frequency of remnants of BCC in lesions interpreted as BLK, we performed step sections on 100 lesions from the trunk of male patients that had been diagnosed as BLK.

Results

Deeper sections revealed remnants of superficial BCC in five and remnants of a melanocytic nevus in two specimens. In the original sections of cases in which a BCC showed up, crusts tended to be more common, whereas vacuolar changes at the dermo-epidermal junction and melanophages in the papillary dermis tended to be less common and less pronounced.

Conclusions

Lesions from the trunk submitted as BCC and presenting histopathologically as a lichenoid interface dermatitis are not always BLKs. Although no confident recommendations can be given on the basis of this limited study, deeper sections may be warranted if lesions are crusted and/or associated with only minimal vacuolar changes at the dermo-epidermal junction and no or few melanophages in the papillary dermis.

Keywords: Basal-cell carcinoma, benign lichenoid keratosis, lichen planus-like keratosis

Introduction

Benign lichenoid keratosis (BLK), or lichen planus-like keratosis (LPLK), is one of the most common diagnoses rendered in dermatopathology. Formerly thought to represent a distinct entity, BLK is now interpreted as the result of an inflammatory reaction directed against a benign epithelial neoplasm, usually a solar lentigo or variants thereof, namely, large-cell acanthoma and reticulated seborrheic keratosis [1,2].

The term “lichen planus-like keratosis” reflects the histopathologic resemblance to lichen planus by virtue of epidermal hyperplasia, a sawtooth pattern of rete ridges, wedge-shaped zones of hyperkeratosis, orthokeratosis, vacuolar changes at the dermo-epidermal junction, individual necrotic keratocytes, and a superficial lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes often accompanied by melanophages. Clinically, lichen planus is not a consideration in patients with a solitary lesion. Among histopathologic features that may distinguish BLK from lichen planus, but that are often missing, are foci of parakeratosis, areas with a diminished granular zone, marked solar elastosis, occasional plasma cells and eosinophils in the infiltrate, and remnants of solar lentigo or reticulated seborrheic keratosis at the edge of the lesion [3].

Although the histopathologic features of BLK are well established, the degree of those changes varies substantially between early and late stages, and minimal histopathologic criteria required for diagnosis of BLK have never been specified. As a consequence, that diagnosis is often rendered in solar lentigines and seborrheic keratoses with only subtle lichenoid changes at the junction and a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes. This being the case, and considering the non-specific nature of BLK, it is not surprising that data concerning the clinical presentation vary. Lesions are said to be mostly solitary, but sometimes multiple; the areas of predilection are said to be arms and upper trunk, but also the face; and both, men and women, have been said to be affected more commonly [1–4]. The individual lesion has been described as a “sharply demarcated, erythematous, violaceous, tan or brown papule or plaque” measuring between 0.3 and 2 mm in diameter [4]. Although “the surface is often scaly” [4], lesions are often misdiagnosed clinically as basal-cell carcinoma (BCC). According to Ackerman et al., “lichen planus-like keratosis usually presents itself as a small papule on the chest or upper part of an arm of a middle-aged person, usually a man. Often it is misinterpreted clinically as a basal-cell carcinoma.” [1]

Because that constellation of findings is very common, the diagnosis of BLK is often rendered in knee-jerk fashion when confronted with a superficial lichenoid dermatitis from the trunk submitted as BCC. However, lichenoid dermatitis is a non-specific tissue reaction that may be encountered in a wide range of lesions, from disorders of immunity to infectious diseases and from melanocytic nevi and melanomas to benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms, the purpose presumably being to wipe out an antigenic stimulus. Because that purpose is at least partially fulfilled, it is not surprising that the triggering stimulus may no longer be detectable in a biopsy specimen. In solitary lesions from the “chest or upper part of an arm of a middle-aged person” interpreted clinically as a basal-cell carcinoma and presenting as a lichenoid dermatitis, the triggering stimulus is usually a seborrheic keratosis, but may also be a BCC.

In other words, clinicians are not always wrong. Sometimes a tiny islet of BCC is left in a lesion that, in all other respects, is typical of BLK, and sometimes that islet is only seen in one of many sections. Having been surprised repeatedly by remnants of BCC in what was considered, at first blush, to be a BLK, we re-examined in many step sections 100 lesions diagnosed as BLK from the trunk of patients that had been submitted under the clinical diagnosis of BCC. The purpose of this study was (1) to assess the frequency of remnants of BCC in lesions interpreted as BLK and (2) to look for histopathologic clues that may indicate a hidden BCC and may prompt deeper sections to be performed.

Materials and methods

We re-evaluated 100 consecutive biopsy specimens from our files submitted under the clinical diagnosis of BCC and diagnosed histopathologically as BLK. In order to reproduce the description of the stereotypical presentation of benign lichenoid keratosis by Ackerman et al., only lesions from the trunk were included. In all cases, the original slide was reviewed and deeper sections were obtained. All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The following parameters were examined: solar elastosis, density of the infiltrate of inflammatory cells, necrotic keratocytes, colloid bodies in the papillary dermis, vacuolar degeneration of the basal cell layer, melanophages, mucin in the papillary dermis, hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, basket-woven orthokeratosis, compact orthokeratosis, mounts of parakeratosis, acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, sawtooth pattern of rete ridges and presence of a crust. Each of those criteria was assessed in four grades, from absent (0), to weak (+), moderate (++), and marked (+++).

Results

Upon review of the original slides, no aggregations of BCC could be detected in any case. In deeper sections, superficial aggregations of BCC appeared in five specimens (5%, Figures 1 and 2). In two lesions, step sections revealed remnants of a melanocytic nevus. The latter cases were excluded from the study. Hence, histopathologic criteria were assessed for five lesions of superficial BCC with a lichenoid infiltrate and 93 lesions of BLK.

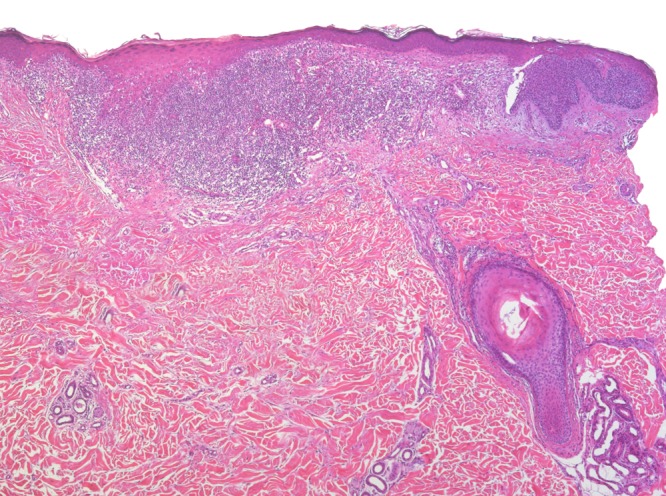

Figure 1a.

Lesion originally diagnosed as BLK. There is a dense lichenoid infiltrate in the upper dermis associated with fibrosis, epithelial hyperplasia, hypergranulosis, and compact orthokeratosis. Step sections revealed remnants of a superficial BCC at the edge of the specimen. [Copyright: ©2016 Kulberg et al.]

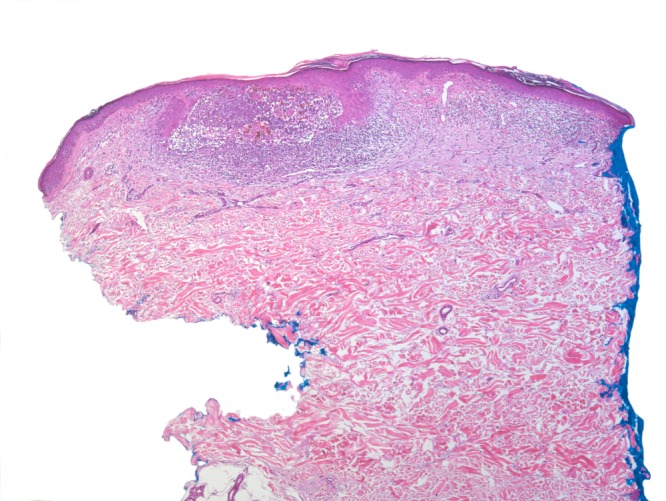

Figure 2a.

Lesion originally diagnosed as BLK. Step sections revealed remnants of a BCC surrounded and interspersed with lymphocytes in the process of regression. At this slightly later stage, the lichenoid interface dermatitis is less pronounced. [Copyright: ©2016 Kulberg et al.]

When the original slides of those lesions were compared, the features most indicative of BCC were crusts (40% BCC vs. 3% BLK), mounts of parakeratosis (0% BCC vs. 27% BLK), and vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction (60% BCC vs. 94% BLK). Vacuolar changes were not only more common but also more pronounced in BLK. Likewise, melanophages tended to be more common in BLKs (67%), being present in a moderate or marked degree in about one-third of the cases. They were absent three of the five cases of BCC and pronounced in only one of them. Weak basal hyperpigmentation was seen in two cases of BCC. It was slightly more common in lesions of BLKs but was classified as moderate in only 5% of those cases. As a clue to a pre-existing pigmented seborrheic keratosis, a more pronounced basal hyperpigmentation may militate against BCC. The same is true for basket-woven orthokeratosis that may indicate a pre-existing seborrheic keratosis and was observed more commonly in BLK. Mucin in the papillary dermis was noted in one case of superficial BCC with lichenoid inflammation. It was somewhat less common in BLK (2 of 93 cases), but in those two cases was even more pronounced than in the case of BCC. None of the other criteria provided any clue to the presence of remnants of BCC in step sections. The criteria and the percentage of expression are listed in the table.

Discussion

Benign lichenoid keratosis (BLK) was first described independently by Lumpkin and Helwig and by Shapiro and Ackerman in 1966. Both pairs of authors were puzzled by noting, in a solitary lesion, histopathologic findings typical of lichen planus and raised the question whether those lesions represented a solitary variant of lichen planus or a previously undescribed separate entity. Lumpkin and Helwig referred to them as “solitary lichen planus,” whereas Shapiro and Ackerman chose the term “solitary lichen planus-like keratosis.” [5,6]

Although Shapiro and Ackerman had emphasized absence of findings suggestive of solar keratosis, such as sparing of adnexal structures, loss of the granular layer and of the “orderly stratified arrangement” of cells, variation of epithelial cells in size and shape, and pronounced cellular atypia [6], subsequent authors interpreted BLK as a variant of actinic keratosis [7,8]. In order to distinguish lesions clearly from actinic keratoses with a lichenoid infiltrate, the term “lichenoid benign keratosis” was introduced in 1976 by Scott and Johnson, who alluded not only to the lack of cellular atypia in BLK but also to the absence of solar elastosis in many cases and to the occurrence of many lesions on the trunk [9].

In 1975, Mehregan noted that, “the periphery of the lesions invariably showed areas of downward budding of pigmented basaloid cells characteristic of lentigo senilis. Toward the center, these epithelial buds were obliterated by the development of an inflammatory cell infiltrate.” The latter was “not always bandlike as that of typical lichen planus, but was occasionally spotty and perivascular.” Despite those deviations from previous descriptions, lesions were essentially the same as those reported as lichen planus-like keratosis: their center resembled lichen planus by virtue of “liquefaction degeneration of basal cells with incontinence of pigment” and “epidermal thickening with hypergranulosis and hyperkeratosis.” Mehregan considered BLK to be “an inflammatory variant of lentigo senilis.” [10]

Other authors confirmed Mehregan’s observations. Although remnants of a solar lentigo or reticulated seborrheic keratosis are not always detectable, they are found often and may serve as a clue to the diagnosis [11]. Absence of such remnants has prompted some authors, to this date, to interpret BLK as a distinct entity unrelated to solar lentigines and seborrheic keratoses [12,13]. However, in a lesion undergoing regression, failure to detect remnants of it must be expected. In clinical studies, BLK has been found to show “a rather consistent association with senile lentigines.” [14] Moreover, stages in the evolution of the pigmented macule of solar lentigo to the violaceous plaque of BLK, followed by complete disappearance of the lesion, have been documented in several studies [15–17]. In molecular studies, many BLKs have been found to harbor mutations commonly found in solar lentigines and seborrheic keratoses [18].

In brief, there is ample evidence that most solitary lesions displaying histopathologic features reminiscent of lichen planus are solar lentigines/reticulated seborrheic keratoses affected by a lichenoid tissue reaction. If the term BLK is to maintain any specific meaning, it should be reserved to those lesions. If used in broader, non-specific fashion, i.e., for various types of regressing neoplasms affected by a lichenoid tissue reaction, it necessarily includes not only viral warts but also some solar keratoses, squamous-cell carcinomas, melanocytic nevi, and melanomas. In fact, it has been proposed to classify lichenoid keratoses into lesions “(1) associated with epithelial changes (lichenoid: seborrheic/actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, verruca, solar lentigo); (2) associated with melanocytic changes (lichenoid: melanocytic nevus, lentigo maligna, melanoma); and (3) miscellaneous (lichen planus, drug eruption, lupus erythematosus, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma).” [19] Evidently, any usefulness of the term “lichenoid keratosis” is sacrificed by that approach.

In general, BLK is considered to represent an inflamed, regressing variant of solar lentigo/seborrheic keratosis. Other types of lesions affected by a lichenoid tissue reaction are regarded as differential diagnoses of BLK. The difficulty of differential diagnosis has been emphasized in various articles. Especially, distinction from melanocytic lesions undergoing regression may be both challenging and important. In our study, 2 of 100 lesions diagnosed originally as BLK revealed remnants of a melanocytic nevus in deeper sections. This is consonant with data from the literature. In a study of 336 BLKs in which deeper sections were obtained, two lesions proved to be regressing melanocytic nevi [20]. In an even larger study comprising more than 1000 cases originally diagnosed as BLK, 14 melanocytic nevi and 6 melanomas were identified [21]. In the original sections, the melanocytic proliferation may be masked by the dense lichenoid infiltrate at the dermo-epidermal junction. Vice versa, BLK may simulate a melanocytic nevus by the combined presence of lymphocytes and pigmented keratocytes with vacuolar alteration at the dermo-epidermal junction, sometimes leading to “pseudomelanocytic nests.” In cases of doubt, immunohistochemical confirmation of a melanocytic proliferation, or absence of it, is essential, and even then caution is advisable because markers of melanocytes, such as Melan-A, may be falsely positive [22]. Particularly challenging are cases in which the original lesion has regressed completely, leaving behind a superficial scar with coarse bundles of collagen in a thickened papillary dermis, telangiectases oriented mostly perpendicular to the skin surface, and melanophages. Although some findings favor a regressed melanoma, such as large diameter and a dense horizontal band of melanophages, and others a regressed BLK, such as foci of wedge-shaped hypergranulosis and clusters of necrotic keratocytes in the papillary dermis, a definite distinction between both conditions may be impossible [23].

Although large series of cases diagnosed as BLK have been reviewed in several studies in which deeper sections have been cut in search for other types of lesions, regressing BCC masquerading as BLK has never been emphasized. This is surprising considering the clinical diagnosis of BCC in many cases of BLK, especially those from the trunk, and the well-known tendency of BCC to regress. It has been estimated that 50% of BCCs show histopathologic evidence of partial regression [24]. In superficial BCCs, that proportion is even higher: foci devoid of neoplastic epithelial cells and characterized by a thickened papillary dermis with many fibroblasts and dilated, tortuous blood vessels are the rule, rather than the exception, contributing to the phenomenon of a seemingly “multicentric” lesion. Because regression of both, superficial BCC and BLK, is mediated by a dense superficial infiltrate of lymphocytes [25], confusion of both events is likely to occur in the absence of remnants of BCC or solar lentigo/seborrheic keratosis, respectively.

In our review of 100 lesions diagnosed histopathologically as BLK, the clinical diagnosis of BCC could be confirmed by cutting deeper sections in five lesions. The small size of aggregations of BCC, the dense lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes surrounding or infiltrating them, and the non-specificity of that inflammatory reaction militate against the possibility of a collision of two independent phenomena and strongly suggest interpretation of those cases as BCC undergoing regression. The same applies to remnants of other neoplasms, such as nests of a melanocytic nevus that turned up in two additional cases. There was no evidence of solar keratosis in any of our cases, probably because only lesions from the trunk of patients have been included. In brief, BCC was the neoplasm overlooked most commonly in lesions from the trunk. Given the tendency of superficial BCC to regress that may be even more pronounced in lesions already showing definite signs of regression, the relatively low number of overlooked BCCs may have little impact. Nonetheless, foci of regression in a BCC do not imply regression of the entire lesion. Portions of a BCC may continue to expand while others regress. The morphologic pattern of “multicentric” BCC has been attributed to “successive phases of growth and regression of the neoplasm.” [26] In any event, the diagnosis of BLK was a misdiagnosis in five cases included in our study and, even more embarrassing, a histopathologic misdiagnosis overruled a correct clinical diagnosis.

Even with step sections, that mistake cannot be avoided entirely. Nonetheless, deeper sections enhance the chance of finding remnants of the original lesion. Considering effort and costs, clues as to whether deeper sections should be ordered are desirable. Because of the limited number of lesions examined, no confident recommendation can be given on the basis of this study. Nonetheless, the presence of crusts in concert with only minimal vacuolar alteration at the dermo-epidermal junction and no or few melanophages in the papillary dermis may justify deeper sections, whereas basket-woven orthokeratosis with mounts of parakeratosis and hyperpigmentation of the basal layer may reassure of the diagnosis of BLK.

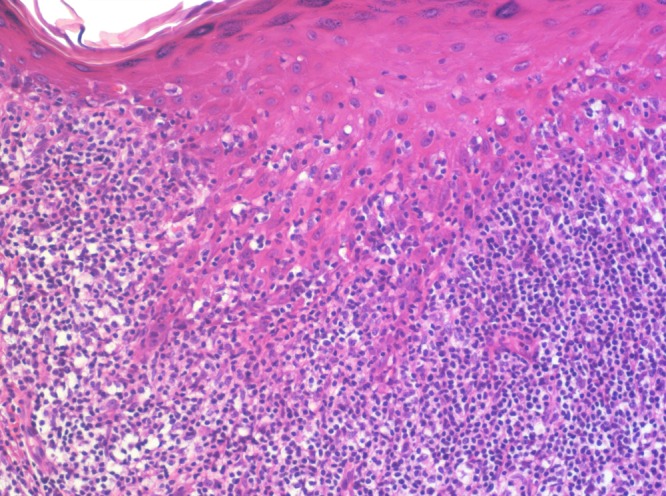

Figure 1b.

Epithelial hyperplasia with a “sawtooth” pattern of rete ridges, hypergranulosis, and orthokeratosis. There are only minimal vacuolar changes at the dermo-epidermal junction and but a few necrotic keratocytes. Numerous lymphocytes are present at the junction and in the lower half of the spinous zone. [Copyright: ©2016 Kulberg et al.]

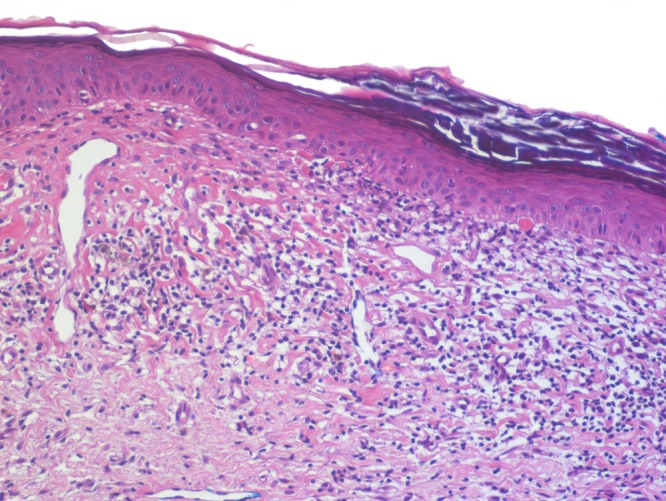

Figure 2b.

The epidermis is atrophic and infiltrated by only few lymphocytes. There are no vacuolar changes at the junction. Remnants of necrotic keratocytes present themselves as “colloid bodies” beneath the basement membrane. The superficial dermis is fibrotic and harbors a few melanophages. [Copyright: ©2016 Kulberg et al.]

TABLE 1.

Criteria examined with degree of positivity in BCC and BLK. [Copyright: ©2016 Kulberg et al.]

| Criteria | BCC (%) n = 5 | BLK (%) n = 93 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| any degree | 0 - + - ++ - +++ | any degree | 0 - + - ++ - +++ | |

| Crusts | 40 | 60 - 20 - 20 - 0 | 3 | 97 - 2 - 1 - 0 |

| Mounts of parakeratosis | 0 | 100 - 0 - 0 - 0 | 27 | 73 - 17 - 10 - 0 |

| Vacuolar alteration | 60 | 40 - 20 - 40 - 0 | 94 | 6 - 23 - 42 - 29 |

| Melanophages | 40 | 60 - 20 - 0 - 20 | 67 | 33 - 38 - 27 -2 |

| Basal hyperpigmentation | 40 | 60 - 40 - 0 - 0 | 47 | 53 - 42 - 5 - 0 |

| Basket-woven orthokeratosis | 20 | 80 - 0 - 20 - 0 | 64 | 36 - 57 - 7 - 0 |

| Mucin in papillary dermis | 20 | 80- 20 - 0 - 0 | 2 | 98 - 0 - 2 - 0 |

| Colloid bodies in papillary dermis | 40 | 60 - 0 - 20 - 20 | 47 | 53 - 17 - 20 - 10 |

| Necrotic keratocytes | 80 | 20 - 40 - 20- 20 | 85 | 15 - 37 - 30 - 18 |

| Hypergranulosis | 40 | 60 - 0 - 40 - 0 | 64 | 36 - 45 - 18 - 1 |

| “Sawtooth” pattern of rete ridges | 20 | 80 - 20 - 0 - 0 | 22 | 78 - 13 - 9 - 0 |

| Elongated rete ridges | 40 | 60 - 0 - 0 - 40 | 61 | 39 - 33 - 24 - 4 |

| Compact orthokeratosis | 40 | 60 - 40 - 0 - 0 | 53 | 47 - 37 - 16 - 0 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltrate | 100 | 0 - 0 - 40 - 60 | 99 | 1 - 9 - 29 - 61 |

| Solar elastosis | 100 | 0 - 40 - 60 - 40 | 99 | 1 - 27 - 59 - 13 |

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Ackerman AB, White W, Guo Y, Umbert I. Differential Diagnosis in Dermatopathology IV. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1994. pp. 122–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. London: Churchill Livingston; Elsevier: 2010. pp. 47–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackerman AB, Niven J, Grant-Kels JM. Differential Diagnosis in Dermatopathology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1982. pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, McKee PH. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 231–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lumpkin LR, Helwig EB. Solitary lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:54–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro L, Ackerman AB. Solitary lichen planus-like keratosis. Dermatologica. 1966;132:386–92. doi: 10.1159/000254438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch P, Marmelzat WL. Lichenoid actinic keratosis. Dermatologia Int. 1967;6:101–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1967.tb05246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinkus H. Lichenoid tissue reactions. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:840–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.107.6.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott MA, Johnson WC. Lichenoid benign keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1976;3:217–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1976.tb00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehregan AH. Lentigo senilis and its evolutions. J Invest Dermatol. 1975;65:429–33. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12608175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to Diagnosis in Dermatopathology II. Chicago: ASCP Press; 1992. pp. 265–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang KA, Kim SH, Choi JE, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Lichenoid keratosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:511–6. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.107236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HS, Park EJ, Kwon ICH, Kim KH, Kim KJ. Clinical and histopathologic study of benign lichenoid keratosis on the face. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:738–41. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318281cd37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laur WE, Posey RE, Waller JD. Lichen planus-like keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:329–36. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berman A, Herszenson S, Winkelmann RK. The involuting lichenoid plaque. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barranco VP. Multiple benign lichenoid keratoses simulating photodermatoses: Evolution from senile lentigines and their spontaneous regression. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:201–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan MB, Stevens GL, Switlyk S. Benign lichenoid keratosis. A clinical and pathologic reappraisal of 1040 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:387–92. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000175533.65486.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groesser L, Herschberger E, Landthaler M, Hafner C. FGFR3, PIK3CA and RAS mutations on benign lichenoid keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:784–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaun RS, Dutta B, Helm KF. A proposed new classification system for lichenoid keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:772–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalton SR, Fillman EP, Altman CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:706–9. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan MB, Stevens GL, Switlyk S. Benign lichenoid keratosis. A clinical and pathologic reappraisal of 1040 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:387–92. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000175533.65486.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beltraminelli H, El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Melan-a-positive “pseudomelanocytic nests”: A pitfall in the histopathologic and immunohistochemical diagnosis of pigmented lesions on sun-damaged skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:305–8. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31819d3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ackerman AB, White W, Guo Y, Umbert I. Differential Diagnosis in Dermatopathology IV. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1994. pp. 126–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnetson RS, Halliday GM. Regression in skin tumours: a common phenomenon. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:S30–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1997.tb01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt MJ, Halliday GM, Weedon D, Cooke BE, Bernetson RS. Regression in basal cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franchimont C, Piérard GE, Van Cauwenberge D, Damseaux M, Lapiére CH. Episodic progression and regression of basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:305–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]