Abstract

Verbal/psychological homophobic bullying is widespread among sexual minority youths. Homophobic bullying has been associated with both high internalized homophobia and low self-esteem. The objectives were to document verbal/psychological homophobic bullying among sexual minority youths and to model the relationships between homophobic bullying, internalized homophobia and self-esteem. Method: A community sample of 300 sexual minority youths aged 14 to 22 years old was used. A structural equations model was tested using a nonlinear, robust estimator implemented in Mplus. The model postulated that homophobic bullying impacts self-esteem both directly and indirectly, via internalized homophobia. Results: 60.7% of the sample reported at least on form of verbal/psychological homophobic bullying. The model explained 29% of the variance of self-esteem, 19.6% of the variance of internalized homophobia and 5.3% of the verbal/psychological homophobic bullying. The model suggests that the relationship between verbal/psychological homophobic bullying and self-esteem is partially mediated by internalized homophobia. Conclusion: Our results underscore the importance of initiatives to prevent homophobic bullying in order to prevent its negative effects on well-being of sexual minority youths.

Keywords: internalized homophobia, homophobic bullying, self-esteem, sexual minority, youths

Results from studies conducted in the USA and Canada have shown that homophobic bullying is widespread among sexual minority youths1–3. Indeed, up to 87% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans-identified, or questioning (LGBTQ) youths have been victims of at least one form of homophobic bullying. Although homophobic bullying can take various forms (e.g. psychological or verbal, physical, sexual, etc.), some studies1,3 have suggested that psychological or verbal bullying is the more common form of homophobic bullying. Among LGBQ senior high school students, humiliation and/or teasing (M=52.1%, F=48.3%), damage to reputation (M=46.2%, F=51.7%) and exclusion and/or rejection (M=36.2%, F=33.9%) are the three more common forms of homophobic bullying4.

Althought homophobic bullying is prevalent among LGBTQ youths, they do not represent an homogenous group and the specific forms or correlated of victimization experienced may differ considerably. Rates of homophobic bullying vary according to gender identity and age. Many studies suggest that sexual minority boys are more likely to report verbal homophobic bullying based on sexual orientation1,2,5 compared to their female counterparts. Taylor and Peter’s results3 suggest that trans-identified youths are at higher risk of suffering from verbal homophobic buylling than LGB boys and girls. However, as they get older, youths tend to report lower rates of both physical and verbal homophobic bullying6.

According to the classical definition of the sociometer hypothesis, self-esteem refers to “an internal, subjective index or marker of the degree to which the individual is being included versus excluded by other people”7 (p519). As argued elsewhere by Leary8, however, it is more appropriate to conceptualize self-esteem as a signal of one’s relational value. Relational value can be defined as “the degree to which a person regards his or her relationship with another individual as valuable, important, or close”9 (p6). Therefore, the function of self-esteem could be to notice any impairment in the inclusionary status or relational value of each individual7,8. Hence, as a consequence of real or perceived bullying, youths may experience a feeling of exclusion and a deterioration of their perceived relational value, resulting in lower self-esteem. Such results have been reported independently of sexual orientation10,11. Homophobic bullying could also have substantial deleterious effects on the self-esteem of LGBTQ youths. LGBT reporting homophobic bullying are more likely to report lower self-esteem12,13. Yet, few studies have tried to evaluate which form of homophobic bullying was specifically related to self-esteem. Nevertheless, a study conducted with sexual minority males in their early adulthood revealed that verbal harassment and discrimination based on sexual orientation were associated with low levels of self-esteem, but not physical homophobic bullying14. This association between homophobic bullying and self-esteem appears to be of special interest.

Sexual minorities are confronting specific challenges related to their sexual minority status, such as acquiring a positive identity while experiencing social stigma and exclusion15. Internalized homophobia (IH), defined as “the application of anti-LGB stigma to the self”15 (p234), is one possible consequence of intimidation based on non-exclusive heterosexuality. There are few studies that have assessed the impact of peer bullying on IH among youths16. Nevertheless, Willoughby, Doty, and Malik17 have shown that homophobic bullying among GLB and queer youths and young adults is associated with a negative LGB identity, a concept reflecting IH, needs for privacy and acceptance regarding sexual orientation, and difficulties in accepting one’s sexual orientation. Furthermore, recent studies have revealed that heterosexist harassment, rejection and discrimination is related to IH among adult gay men, bisexual men, questioning men, and lesbian women18,19. Thus, not only homophobic bullying impairs self-esteem, but it may also increase IH among LGBTQ youths. Also, a recent review by Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, and Meyer20 revealed that sexual minority men and women reporting high levels of IH are more likely to report low levels of self-esteem, suggesting that homophobic bullying impacts self-esteem both directly and indirectly, through IH.

Both lower self-esteem and IH have been associated with negative outcomes. Recent studies, including meta-analysis, have shown that both factors increased psychological distress, depression and anxiety21–25. Lower self-esteem has also been associated to physical dating violence victimization among males26, suicidal ideation27, suicidal attempt28 and long-term impacts such as mental and physical health problems, criminal convictions, and fewer economic prospects in later adult life29. IH also appears to be a strong predictor of posttraumatic stress symptoms among LGB youths, even after controlling for variables such as verbal and physical homophobic bullying, stressful live events, gender, etc.30

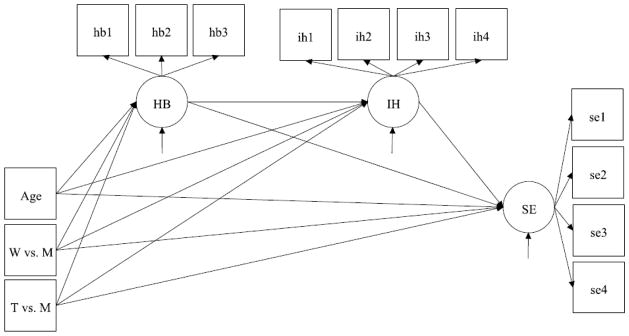

Given the importance of self-esteem for mental health and well-being among sexual minority youths and the centrality of homophobic bullying in youths’ lives, the current study aims to document verbal/psychological homophobic bullying among LGBTQ youths and young adults and to model the relationships between homophobic bullying, IH and self-esteem. The hypotheses are: 1) that male will show higher rates of homophobic bullying than female, and that transidentified youths will show higher rates of homophobic bullying than male; and 2) that bullying impacts self-esteem both directly and indirectly, via IH and that these relationships hold when controlling for gender and age (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mediation model of HB on SE through IH

Note: SE = Self-Esteem. IH = Internalized Homophobia. HB = Homophobic Bullying. W vs. M = Women compared to Men. T vs. M = Transidentified compared to Men.

METHOD

Data for this study are drawn from the Quebec Youths’ Romantic Relationships survey. The questionnaire included self-reported measures on a variety of dimensions relevant to the study of victimization and took approximately 40 minutes to complete. The research ethic boards of the Université du Québec à Montréal approved this project. Participants agreed to participate on a voluntary basis by signing a consent form, either on paper or electronically.

Sample and procedure

Data were collected among youths aged 14 to 22 through a web-based survey targeting Quebec LGBTQ youths. Two main recruitment strategies were used. A general strategy was Facebook ads targeting youths aged 14–22 with interests in sexual minorities. Specific strategies consisted in publicizing the survey through both active and passive online recruitment (publicity banners on websites targeting LGBTQ youths and using mailing lists identified by key informants) and snowballing. These participants were assigned a stratum based on their region of residence; a common cluster belonging to take into account the non-independence of the observations among the community sample; and a sample weight based on age, gender and sexual orientation (attraction and behavior) as reported in two representative Quebec studies of youths31 and Hébert et al. (ongoing study). The current study was composed of 300 non-exclusively heterosexual participants.

Variables

Sociodemographics. Data were collected on age (in years), sex at birth and transidentity. Transidentity was questioned using the following item: When their sex at birth and their gender identity (sense of belonging to one sex) do not match, some people define themselves as a trans person (transgender, transsexual, trans-identified). Do you consider yourself as a trans person? Sex at birth and transidentity were combined to create three categories: men (M), women (W), transidentified participants (T). Dummy variables comparing women and trans to men were created (W vs. M, T vs. M)

Psychological/verbal homophobic bullying (HB). Participants were questioned on three specific forms of psychological/verbal prejudice, based on Chamberland et al. study31. The question was: During the last 6 months, how frequently did you experience the following situations because people think that you might be gay/lesbian/bisexual or trans or because you are gay/lesbian/bisexual or trans? Three forms of homophobic bullying were covered: exclusion and rejection (HB1); humiliation (HB2); damage to the reputation (HB3). For each prejudice, a five anchors nominal scale was created: Never (1), Rarely (2), Sometimes (3), Often (4), and Always (5). These three forms of intimidation correspond to psychological homophobic bullying/teasing. The three items showed a high internal consistency (α = .87).

Self-esteem (SE). Self-esteem was evaluated with 4 items from the Self-Description Questionnaire (SDQ)32. Participants had to choose the answer that best describes how they feel concerning the following statements: Overall, I have a lot to be proud of (SE1), In general, I like myself the way I am (SE2), I like the way I look (SE3) and When I do something, I do it well (SE4). Response options were: False (0), Mostly false (1), Sometimes false/Sometimes true (2), Mostly true (3), and True (4). The scale showed a high internal consistency (α = .85).

Internalized homophobia (IH). Internalized homophobia was measured with four items from the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS)33. The instruction was: For each of the following statements, mark the response that best indicates your experience as a lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) person. Please be as honest as possible in your responses. The four items were: I would rather be straight if I could (IH1), I wish I were heterosexual (IH2), I am glad to be an LGB person (IH3), and My life would be more fulfilling if I were heterosexual (IH4). The response options were: Strongly disagree (1), Disagree (2), Somewhat disagree (3), Somewhat agree (4), Agree (5), Strongly agree (6). The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was good (α = .82).

Analyses

Rates of prejudice based on sexual orientation according to gender were estimated with their 95% confidence interval. A structural equations model (SEM) was tested with the Mplus software, v.7.1134, using a nonlinear, robust estimator (WLSMV) and taking into account the complex sample (stratification, clustering and sampling weights). The lowest value of the covariance coverage, measuring the proportion of non-missing data in the covariance matrix, was 0.760. Missing data were handled with the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) implemented in Mplus. The χ2 test was used to detect potential misspecifications in the hypothesized model. A non-significant χ2 value, a RMSEA value < 0.05, and values of CFI and TLI > 0.90 were considered to indicate an adequate fit of the model35.

Results

Participants (n = 300) were aged between 14 and 22 years old (M = 17.9, SD = 2.02). More women (63.7%) than men (36.3%) participated to the study. The majority of the participants were from urban agglomeration (86.3%). Regarding sexual attraction, 73.7% of the participants described themselves as homosexual, 15.3% as bisexual; 7.7% reported a predominantly heterosexual attraction and 3.3% reported being unsure. Thirteen (13) percent of the participants identified themselves as trans or questioning their gender identity.

Table 1 presents the rates of homophobic bullying by gender identity. About half (48.4%) of the participants suffered from damage to reputation or reported at least one episode of humiliation (48.0%), and a third (34.3%) have felt excluded or rejected. Sixty-one (60.7) percent of the sample reported at least on form of verbal/psychological homophobic bullying. There were no statistically significant differences between homophobic bullying rates according to gender identity, although women tend to report higher rates.

Table 1.

Rates of verbal/psychological homophobic bullying, by gender identity (n = 277)

| Prevalence n (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least once | Women | Men | Transidentified | |

| Exclusion and rejection | 95 (34.3) | 51 (53.7) | 28 (29.5) | 16 (16.8) |

| Humiliation | 133 (48.0) | 65 (48.9) | 50 (37.6) | 18 (13.5) |

| Damage to the reputation | 134 (48.4) | 72 (53.7) | 41 (30.6) | 21 (15.7) |

| Any forms | 168 (60.7) | 86 (51.2) | 58 (34.5) | 24 (14.3) |

Frequencies for the three forms of verbal/psychological homophobic bullying under study are presented in Table 2. Among youths who reported at least one episode of homophobic bullying, 7.6 to 11.2% indicated that they were “often” or “always” victimized.

Table 2.

Specific forms of homophobic bullying based on sexual minority status (n = 277)

| Rarely n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Often or always n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusion and rejection | 43 (15.5) | 31 (11.2) | 21 (57.6) |

| Humiliation | 60 (21.7) | 42 (15.2) | 31(11.2) |

| Damage to the reputation | 51 (18.4) | 55 (19.9) | 28 (10.1) |

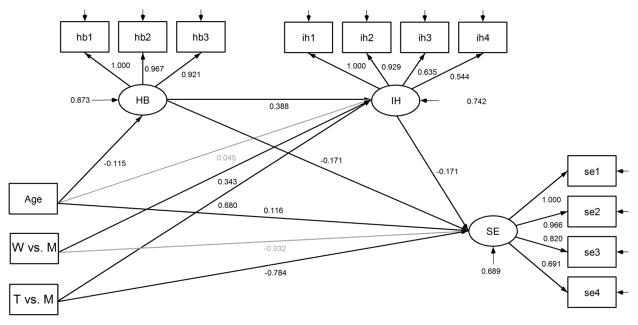

The theoretical model described in Figure 1 was tested. The χ2 statistic for the hypothesized models was 79.66 (df = 65), p-value = .104, suggesting that the tested model did not differed significantly from the data. The two non-significant paths were removed (W vs. M→HB and T vs. M→HB). The revised model (see Figure 2) fit the data well (χ2 = 79.67, df = 67, p = 0.138). The good fit of the model was also supported by an averaged RMSEA value of 0.025 as well as CFI and TLI values over 0.98.

Figure 2. Revised model (standardized coefficients).

Note: SE = Self-Esteem. IH = Internalized Homophobia. HB = Homophobic Bullying. W vs. M = Women compared to Men. T vs. M = Transidentified compared to Men. The numbers on the straight, single-headed arrows are path coefficients. The small arrows pointing to HB, IH and SE are residual variances, reflecting the proportion of variance that cannot be explained by the independent variables. All coefficients are standardized. All coefficients were significant at the 5% level, except for Age → IH and W vs. M → SE (in gray).

The model explained 29% of the variance of self-esteem, 19.6% of the variance of internalized homophobia and only 5.3% of the homophobic bullying. The signs of all the coefficients were in the expected direction. The total (direct and indirect) effect of homophobic bullying on self-esteem was negative and significant. The model suggests that the relationship between homophobic bullying and self-esteem is partially mediated by internalized homophobia among sexual minority youths.

Effects of gender are worth noticing. Internalized homophobia was higher among women and transidentified compared to men. The total effect of women gender on self-esteem was non-significant (unstandardized coefficient = -0.09, s.e. = 0.15, p=0.55), while only the direct effect for transidentified gender was significant (unstandardized coefficient = -0.90, s.e. = 0.11, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Like previous researchers have shown, the results of the current study revealed that verbal/psychological homophobic bullying among LGBTQ is widespread. Nearly half of youths reported damage to reputation or humiliation because of their sexual orientation, with 10% of which mentioned experiencing this form of bullying often or more. Contrary to many studies, we did not find a significant relationship between gender and homophobic bullying. Possible explanations are the general high rate of homophobic bullying in all groups and the lack of power due to sample size of gender subgroups. Another study among Quebec youths showed similar rates of homophobic bullying prevalence and no differences according to gender4.

Age was the only variable predictive of homophobic bullying. As reported by others6, as youths become older, they tend to experience, or at least report, less homophobic bullying. This is consistent with the fact that bullying in general (not exclusively homophobic bullying) seems to be more prevalent among 6th through 8th grade students compared to 9th and 10th grade students36. The final model explained only 5% of the variance of homophobic bullying. Future studies might include other variables such as disclosure of sexual orientation13, gender nonconformity18 as well as socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of the social environment as predictors of homophobic bullying among sexual minority youths to better understand its determinants.

As hypothesized, homophobic bullying impacts self-esteem both directly and indirectly through internalized homophobia. In our study, participants who were victims of homophobic bullying were more likely to report low levels of self-esteem. These results suggest that homophobic bullying is likely to generate a general signal of rejection and of threat regarding one’s relational value, and thus decreases self-esteem, independently of the internalization of the homophobic stigma. Therefore, it is possible that the mere fact of being bullied, notwithstanding the homophobic nature those detrimental behaviors, is a good indicator to the self that one’s relational status could be impaired, resulting in low levels of self-esteem.

Similar to results found by other studies presented above18,19, we found that LGBTQ youths who were bullied because of their sexual orientation also reported higher levels of IH. Feinstein et al.18 argued that their results are coherent with the psychological mediation framework of Hatzenbuehler37. Hatzenbuehler’s framework postulates that stigma related stressors, such as bullying, can lead to group specific processes, such as internalized homophobia. Thus, it can be argued, as suggested by Allport38, that when a minority group suffer from discrimination and disparagement, some individuals may react by identifying themselves with the ideas of the majority group, hence developing a sense of self-hate. This “mechanism is involved in cases where the victim instead of pretending to agree with his ‘better’ actually does agree with them, and sees his own group through their eyes”38 (quotation marks and italics are from the original text, p150). In the current study, youths who were bullied because of sexual minority status may have interpreted these prejudices as signs of societal disapproval and condemnation of sexual minority behaviors and status, thus internalizing the anti-LGBTQ stigma.

IH was also predictive of low self-esteem. It is possible that the internalization of homophobic stigma leads LGBTQ youths to fear future rejection, impairing their sense of relational value and their self-esteem. Transidentified youths reported higher levels of IH and lower levels of self-esteem than men. One interpretation is that transidentified youths were more victimized than other sexual minority youths in domains unmeasured in the current study (e.g. bullying based on gender nonconformity)6, and that they were intimidated for a greater length of time. That woman also reported higher internalized homophobia than men was surprising and cannot be explained by the variables included in this study. Clearly future investigations are necessary to ascertain these interpretations.

Limitations

Some limitations of the study must be stated. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the data prevents any conclusion on the causal relationship between variables. Nevertheless, a longitudinal study revealed that peer victimization was predictive of later self-esteem levels11, suggesting that the direction of the core relationship under study (homophobic bullying and IH) is plausible. Secondly, since we used a community-based sample, it is difficult to assess the representativeness of our sample. Gay and bisexual men, which are more likely to be bullied according to many studies, were also less likely than women to participate in the current study. As for transidentified people, they are difficult to recruit and their small number in the sample leads to a lack of statistical power to detect differences. Thirdly, beside sociodemographic variables, the current model included no determinants of homophobic bullying. Similarly, we evaluated only emotional and psychological forms of homophobic bullying. To better understand the phenomenon of bullying based on sexual orientation and its consequences, other studies should try to include variables that could predict homophobic bullying (e.g. gender nonconformity), and evaluate different forms of homophobic bullying (e.g. physical, sexual, etc.). Finally, all measures were self-reported. It is therefore possible that bias were present in the data. For example, it is possible that those with high IH remember more homophobic bullying episodes than those with low IH.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study offers relevant data to sustain a better understanding of the realities of verbal/psychological homophobic bullying in LGBT youth and the relationships between homophobic bullying, IH and self-esteem. Our results clearly underscore the importance of initiatives to prevent homophobic bullying in order to prevent its negative effects on well-being of LGBTQ.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca) grant(s) FRN: 103944. The authors wish to thank Isabelle Bédard and Kathleen Boucher for their work in previous phases in the project as well as the community-based organizations involved in the recruitment and all the youths that participated in the study.

References

- 1.D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J Interpers Violence [Internet] 2006 Nov;21(11):1462–82. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293482. [cited 2012 Aug 25] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17057162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor C, Peter T, McMinn TL, Elliott T, Beldom S, Ferry A, et al. The first national climate survey on homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia in Canadian schools [Internet] Toronto, ON: Egale Canada Human Rights Trust; 2011. Every Class in Every School; p. 151. Available from: http://www.egale.ca/EgaleFinalReport-web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberland L, Richard G, Bernier M. Les violences homophobes et leurs impacts sur la persévérance scolaire des adolescents au Québec. Rech Éducations. 2013;8(1):99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: the influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. J Youth Adolesc [Internet] 2009 Aug;38(7):1001–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3707280&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosciw JG, Greytak Ea, Diaz EM. Who, what, where, when, and why: demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Youth Adolesc [Internet] 2009 Aug;38(7):976–88. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9412-1. [cited 2013 Sep 19] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19636740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leary MR, Tambor ES, Terdal SK, Downs DL. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol [Internet] 1995;68(3):518–30. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leary MR. Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. Eur Rev Soc Psychol [Internet] 2005 Jan;16(1):75–111. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10463280540000007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leary MR. Toward a conceptualization of interpersonal rejection. In: Leary MR, editor. Interpers Rejection. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Moore M, Kirkham C. Self-esteem and its relationship to bullying behaviour. Aggress Behav [Internet] 2001 Jul;27(4):269–83. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ab.1010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overbeek G, Zeevalkink H, Vermulst A, Scholte RHJ. Peer Victimization, Self-esteem, and Ego Resilience Types in Adolescents: A Prospective Analysis of Person-context Interactions. Soc Dev [Internet] 2010 May;19(2):270–84. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00535.x. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell ST, Ryan C, Toomey RB, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: implications for young adult health and adjustment. J Sch Health [Internet] 2011 May;81(5):223–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00583.x. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21517860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldo CR, Hesson-McInnis MS, D’Augelli aR. Antecedents and consequences of victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people: A structural model comparing rural university and urban samples. Am J Community Psychol. 1998 Apr;26(2):307–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1022184704174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of Harassment, Discrimination, and Physical Violence Among Young Gay and Bisexual Men. Am J Public Health [Internet] 2004 Jul;94(7):1200–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1200. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohr JJ, Kendra MS. Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale. J Couns Psychol [Internet] 2011 Apr;58(2):234–45. doi: 10.1037/a0022858. [cited 2012 Oct 4] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21319899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collier KL, van Beusekom G, Bos HMW, Sandfort TGM. Sexual orientation and gender identity/expression related peer victimization in adolescence: a systematic review of associated psychosocial and health outcomes. J Sex Res [Internet] 2013 Jan;50(3–4):299–317. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.750639. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23480074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willoughby BLB, Doty ND, Malik NM. Victimization, Family Rejection, and Outcomes of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Young People: The Role of Negative GLB Identity. J GLBT Fam Stud [Internet] 2010 Oct 8;6(4):403–24. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1550428X.2010.511085. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinstein BA, Goldfried MR, Davila J. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. J Consult Clin Psychol [Internet] 2012 Oct;80(5):917–27. doi: 10.1037/a0029425. [cited 2013 Sep 17] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22823860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szymanski DM, Ikizler AS. Internalized heterosexism as a mediator in the relationship between gender role conflict, heterosexist discrimination, and depression among sexual minority men. Psychol Men Masc [Internet] 2013;14(2):211–9. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/a0027787. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szymanski DM, Kashubeck-West S, Meyer J. Internalized Heterosexism: Measurement, Psychosocial Correlates, and Research Directions. Couns Psychol [Internet] 2008 Jul 1;36(4):525–74. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://tcp.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0011000007309489. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciarrochi J, Heaven PCL, Davies F. The impact of hope, self-esteem, and attributional style on adolescents’ school grades and emotional well-being: A longitudinal study. J Res Pers [Internet] 2007 Dec;41(6):1161–78. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0092656607000207. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institut de la Statistique du Québec. Le visage des jeunes d’aujourd’hui: leur santé mentale et leur adaptation sociale. 2013. L’Enquête québécoise sur la santé des jeunes du secondaire 2010–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Clin Psychol Rev [Internet] 8. Vol. 30. Elsevier Ltd; 2010. Dec, Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: a meta-analytic review; pp. 1019–29. [cited 2013 Sep 20] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20708315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does Low Self-Esteem Predict Depression and Anxiety? A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol Bull [Internet] 2012 Jun 25; doi: 10.1037/a0028931. [cited 2012 Jul 20]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22730921. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Wright ER, Perry BL. Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. J Homosex [Internet] 2006 Jan;51(1):81–110. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_05. [cited 2013 Mar 2] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16893827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Suchindran C. Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet] 2004 Nov;39(5):1007–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014. [cited 2012 Mar 11] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15475036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilburn VR, Smith DE. Stress, self-esteem, and suicidal ideation in late adolescents. Adolescence [Internet] 2005 Jan;40(157):33–45. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/hsh/PeresSC/Classes/PSYC6011/Mult Regression - suicide.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maraš JS, Kolundžija K, Dukić O, Marković J, Okanović P, Stokin B, et al. Some psychological characteristics of adolescents hospitalized following a suicide attempt. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci [Internet] 2013 Feb;17(Suppl 1):50–4. [cited 2013 Sep 23] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23436667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Moffitt TE, Robins RW, Poulton R, Caspi A. Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2006 Mar;42(2):381–90. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dragowski Ea, Halkitis PN, Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Sexual Orientation Victimization and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv [Internet] 2011 Apr;23(2):226–49. [cited 2012 Aug 28] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10538720.2010.541028. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamberland L, Émond G, Julien D, Otis J, Ryan W. L’impact de l’homophobie et de la violence homophobe sur la persévérance et la réussite scolaires. Montréal/Québec; 2011. p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsh HW, Neill RO. Self-Description Questionnaire III: The construct validity of multidimensional self-concept ratings by late adolescents. J Educ Meas. 1984;21(2):153–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohr J, Fassinger R. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2000;33(2):66–90. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285(16):2094–100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull [Internet] 2009 Sep;135(5):707–30. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [cited 2013 Mar 2] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2789474&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1966. [Google Scholar]