Abstract

Rationale

In 2007, WHO issued emergency recommendations on empiric treatment of sputum acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear-negative patients with possible tuberculosis (TB) in HIV-prevalent areas, and called for operational research to evaluate their effectiveness. We sought to determine if early, empiric TB treatment of possible TB patients with abnormal chest radiography or severe illness as suggested by the 2007 WHO guidelines is associated with improved survival.

Methods

We prospectively enrolled consecutive HIV-seropositive inpatients at Mulago Hospital in Kampala, Uganda, from 2007 to 2011 with cough ≥2 weeks. We retrospectively examined the effect of empiric TB treatment before discharge on eight-week survival among those with and without a WHO-defined “danger sign,” including fever >39°C, tachycardia >120 beats-per-minute, or tachypnea >30 breaths-per-minute. We modeled the interaction between empiric TB treatment and danger signs and their combined effect on eight-week survival and adjusted for relevant covariates.

Results

Among 631 sputum smear-negative patients, 322(51%) had danger signs. Cumulative eight-week survival of patients with danger signs was significantly higher with empiric TB treatment(80%) than without(64%, p<0.001). After adjusting for duration of cough and concurrent hypoxemia, patients with danger signs who received empiric TB treatment had a 44% reduction in eight-week mortality(Risk Ratio 0.54, 95%CI 0.32-0.91, p=0.020).

Conclusions

Empiric TB treatment of HIV-seropositive, smear-negative, presumed pulmonary TB patients with one or more danger signs is associated with improved eight-week survival. Enhanced implementation of the 2007 WHO empiric-treatment recommendations should be encouraged whenever and wherever rapid and highly sensitive diagnostic tests for TB are unavailable.

INTRODUCTION

In resource-constrained settings with a high HIV prevalence, patients with paucibacillary forms of tuberculosis (TB) are known to experience high case-fatality rates.1 Such patients typically have negative sputum acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smears2 and rarely have access to more sensitive forms of TB diagnostic testing.3 In 2007, recognizing that poor outcomes among this patient sub-group represented a global crisis in need of urgent action, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that clinicians make greater use of empiric TB therapy by starting it immediately and continuing it to completion in all patients with cough of two to three weeks or more, especially when either radiographic findings consistent with TB or physical signs of severe illness are present.4 Because evidence supporting these recommendations was limited at that time, the WHO policy statement specifically called for post-implementation operational research to evaluate their impact. Therefore, we sought to evaluate whether adhering to these guidelines by providing empiric TB treatment to HIV-seropositive patients undergoing evaluation for TB but found to have negative sputum AFB smears was associated with improved survival.

METHODS

Study population and clinical evaluation

This study was nested within the International HIV-associated Opportunistic Pneumonia (IHOP) study in Kampala, Uganda. Between 18th September 2007 and 30th March 2011, we enrolled consecutive HIV-seropositive adults (age ≥18 years) newly admitted to the medical wards of Mulago Hospital with cough of ≥2 weeks’ but <6 months’ duration. The parent study excluded patients with a history of concurrent or prior TB treatment within the previous two years.

We collected clinical and demographic information prospectively using a standardized questionnaire. The routine diagnostic evaluation included vital signs, physical exam, frontal chest radiography, collection of spot (day 1) and early morning (day 2) sputum samples for AFB-smear microscopy and culture, and collection of blood for HIV-antibody testing and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count measurement. Consenting patients underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy for diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), and other opportunistic pulmonary conditions, as previously described.6 The Uganda National TB Reference Laboratory performed all mycobacterial studies according to established protocols, as previously described.7 For this analysis, we included all patients except those with one or more positive sputum AFB smear examinations. At discharge, we asked all patients to return in eight weeks to undergo follow-up clinical examination and to assess vital status.

Treatment decisions

Clinical staff employed by the Uganda Ministry of Health, primarily medical house officers, made all treatment decisions with guidance from supervising physicians. The local standard of care at the time of the study was defined by Uganda's national TB guidelines, which recommended that possible TB patients undergo chest radiography and receive a broad-spectrum, non-fluoroquinolone antibiotic, with TB treatment to be prescribed at the discretion of the individual clinician.8 Although these national guidelines did not explicitly recommend empiric treatment based on HIV status or illness severity, we made clinicians aware of the WHO-recommended approach through posters mounted on the wards. Because sputum smear microscopy was the only rapid diagnostic test for TB routinely available to patients enrolled in this study, we defined any treatment prior to hospital discharge (and prior to receipt of mycobacterial culture results) as “empiric TB treatment.” We notified all patients with positive cultures as soon as the results were available and arranged for them to receive TB treatment immediately.

Analyses

The primary aim of our study was to evaluate the effectiveness of empiric TB treatment as recommended in the 2007 WHO guidelines for reducing mortality among patients in HIV-prevalent areas, especially among patients with severe illness and among those with radiographic abnormalities consistent with active tuberculosis. The WHO guidelines define severe illness based on the presence of any one of the following three “danger signs” at enrollment: fever (axillary temperature >39°C), tachycardia (pulse>120 beats per minute), or tachypnea (respiratory rate >30 breaths per minute).4 The guidelines also include the “inability to walk unaided” as a fourth danger sign, but we omitted this from our definition of severe illness because we had information about ambulatory status available for only a subset of our patients. We defined empiric treatment as any multi-drug therapy for active TB administered before hospital discharge to a patient with negative sputum AFB smears; other than chest radiography, no other form of rapid TB testing was available at the time of the study, including GeneXpert MTB/RIF nucleic acid amplification testing or urinary lipoarabinomannan (LAM) ELISA testing. An on-site attending chest physician who was blinded to all clinical data, test results, and outcomes interpreted all chest radiographs as either consistent with active TB or not. We defined confirmed pulmonary TB based on any positive sputum culture, and confirmed extra-pulmonary TB based on clinician diagnosis at discharge.

We performed bivariate analyses of the associations between clinical variables and the primary predictor, TB treatment prior to hospital discharge, and of their association with the primary outcome, mortality within eight weeks of enrollment. We compared categorical variables using the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, and non-normally distributed continuous variables using the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. We performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to estimate the cumulative incidence of mortality, stratified by empiric treatment status, in subjects with and without severe illness.

Finally, for the overall study population, we calculated risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the effects of empiric TB treatment and danger signs on eight-week mortality, using a multivariate Poisson model with a log link and robust standard errors.9 We constructed models with empiric treatment, danger signs, and chest radiography interpretation as our predictors of primary interest, including an interaction term among them, and we assessed whether greater illness severity as measured by number of danger signs was associated with greater treatment benefit. We adjusted for age, gender, CD4 count, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, prior antiretroviral therapy, temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation, variables which we selected for their face validity, as well as any other variables associated with mortality in bivariate analyses (p<0.2). We assessed for sensitivity to outliers by the sequential exclusion of possibly influential observations, and for sensitivity to the time of outcome assessment by comparing models with different temporal endpoints. We performed sensitivity analyses based on the extreme assumptions that patients lost to follow-up either all died or all survived.

For all analyses, we defined significance in reference to the probability of a two - tailed, type I error (p-value) less than 0.05. Sample size arose from convenience, so, in lieu of power calculations, we estimated the precision of all outcomes using 95% confidence intervals. We performed all statistical analyses using STATA version 11 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics Approval

The IHOP study was approved by the Makerere University Faculty of Medicine Research Ethics Committee, the Mulago Hospital Institutional Review Board, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research. We obtained written informed consent from all participants. In addition, the Yale Human Research Protection Program approved the data analysis portion of this study.

RESULTS

Study population

We identified 631 sputum AFB smear-negative patients among 1190 HIV-seropositive patients evaluated for TB during the study period (Figure 1). The median age was 33 years (inter-quartile range (IQR) 28-40), and 58% were women (Table 1). The median CD4+ T-cell count was 72 cells/μL (IQR 20 – 209 cells/μL). One-hundred seventy-six (28%) patients were newly diagnosed with HIV, 10 (5.7%) of whom had previously tested negative for HIV antibodies. Overall, 347 (76%) were using co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and 133 (29%) were taking anti-retroviral therapy (ART). Three-hundred eighty-one (60%) had received antibiotics prior to hospital admission.

Figure 1. Study Enrollment.

Of 1190 eligible patients evaluated for TB, 631 (53%) were sputum AFB smear-negative and therefore met the study entry criteria. 126 patients were empirically started on anti-tuberculosis medication before hospital discharge while 505 were not treated.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of enrolled patients, stratified by empiric TB treatment status

| Characteristics (n, %) | No Empiric TB Treatment (n=505) | Empiric TB Treatment (n=126) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 296 (59) | 70 (56) | 0.53 |

| Median age (IQR), years | 33 (28-40) | 32 (28-39) | 0.36 |

| Median CD4+ count (IQR), cells/μL | 72 (20-205) | 86 (26-207) | 0.44 |

| Antiretroviral therapy on admission | 113 (22) | 20 (16) | 0.11 |

| CTX prophylaxis | 275 (54) | 72 (57) | 0.59 |

| Antibiotics for current illness | 307 (61) | 74 (59) | 0.67 |

| Productive cough | 459 (91) | 99 (79) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 298 (59) | 73 (58) | 0.83 |

| Weight loss (>5 kg) | 469 (93) | 119 (94) | 0.53 |

| Danger signs | 248 (49) | 74 (59) | 0.053 |

| Fever (T>39°C) | 27 (5) | 13 (10) | 0.041 |

| Tachycardia (HR>120) | 105 (21) | 42 (33) | 0.003 |

| Tachypnea (RR>30) | 195 (39) | 49 (39) | 0.96 |

| Hypoxia (SpO2≤93%) | 170 (34) | 46 (37) | 0.55 |

| Chest radiograph consistent with TB | 277 (65)* | 73 (63)† | 0.78 |

| Mycobacterial culture-positive | 108 (23) | 59 (52) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CTX, co-trimoxazole; HR, heart rate; IQR, interquartile ratio; RR, respiratory rate; SpO2, Oxygen saturation; T, Temperature; TB, tuberculosis.

Legend:

Missing 78 observations

Missing 11 observations

Of 580 sputum AFB smear-negative patients with available culture results, 195 patients (34%) had TB, including 132 (23%) with culture-positive pulmonary TB without clinically diagnosed extra-pulmonary TB, 35 (6.0%) with both culture-positive pulmonary TB and extra-pulmonary TB, and an additional 28 (4.8%) with extra-pulmonary TB without pulmonary TB. Out of all participants, 23 (3.7%) patients had pulmonary Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) (one with concurrent TB) and 14 (2.2%) had Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) (three with concurrent TB) diagnosed on bronchoscopy. Overall, mortality was high, with 117 of the 631 total enrolled patients (19%) dying within four weeks of enrollment, and 156 (25%) dying within eight weeks. Among 145 patients with culture-confirmed TB and available eight-week vital status, 41 (28%) died; a broadly similar proportion of patients without TB (86/340, 25%) died (Risk difference 3.0%, 95% CI −5.7% to +12%).

Clinical characteristics and TB treatment decisions

A large proportion of patients (51%, 322 patients) had danger signs, with 40 (6.3%) having fever, 147 (23%) having tachycardia, and 244 (39%) having tachypnea (Table 1). Two-hundred twenty-eight (36%) had one danger sign, 79 (13%) had two danger signs, and 15 (2%) had three danger signs. Hypoxemia was also common, with 216 (34%) having an oxygen saturation ≤93% by pulse oximetry. Although ambulatory status was not routinely documented, among a subset of 235 patients enrolled late in the study, only three (1.9%) were bed-bound, and all had at least one other danger sign. Among 295 patients with danger signs and available sputum culture results, 91 (31%) had confirmed pulmonary TB.

Five-hundred forty-two (86%) patients had chest radiography performed, and of these, 350 (65%) had findings consistent with TB. Among 324 patients with radiographic findings consistent with TB and available sputum culture results, 91 (28%) had confirmed pulmonary TB.

Clinicians provided empiric TB treatment prior to hospital discharge to 126 (20%) patients, including 74/322 (23%) patients with and 52/309 (17%) patients without danger signs (p=0.053). Among 114 empirically treated patients with available sputum culture results, 59 (52%) were ultimately confirmed to have TB. There were no significant differences between patients treated empirically and those not treated with respect to age, gender, median CD4+ T-cell count, use of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, pre-admission use of ART, or prior antibiotic treatment for the current respiratory illness. There was no association between the number of danger signs and the likelihood of empiric TB treatment, with 52 (17%) of those with zero danger signs, 48 (21%) of those with one danger sign, 22 (28%) of those with two danger signs, and 4 (27%) of those with three danger signs being empirically treated (p=0.22 by Wald test for linear trend). Similarly, empiric TB treatment was equally likely whether chest radiographic findings were consistent with TB (21%) or not (22%, RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.68-1.3, p=0.78). However, empiric treatment was more likely among patients with cough that was non-productive (37% vs. 18%, RR 2.1, 95% CI 1.5-3.0, p<0.001), among patients with fever (32% vs. 19%, RR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1-2.7, p=0.041), and among patients with tachycardia (29% vs. 17%, RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2-2.3, p=0.003). Patients receiving empiric TB treatment were more likely to have culture-positive TB (52%) than patients not receiving empiric TB treatment (23%, RR 2.2, 95% CI 1.8-2.8, p<0.001).

Survival outcomes

The cumulative eight-week survival of patients with danger signs was 17% higher (95% CI +4.8% to +29% for difference, p=0.013) among those who received empiric TB treatment (78%, 95% CI 66%-87%) than among those who did not (61%, 95% CI 54%-67%) (Figure 2), giving a number-needed-to-treat of approximately six individuals treated to save one additional life. The survival benefit associated with empiric TB treatment compared to no empiric treatment was similar whether one danger sign (Risk difference 15%, 95% CI 0.01% to +29%, p=0.049) or two danger signs (Risk difference 16%, 95% CI −8.7% to +41%, p=0.20) were present, but we observed the largest survival benefit (p<0.0001 by Wald test for departure from linear trend) among patients with three danger signs (Risk difference 50%, 95% CI +19% to +81%, p=0.002). Among those without danger signs, however, survival was broadly similar among those who were treated empirically (78%, 95% CI 63%-89%) and those who were not treated empirically (76%, 95% CI 70%-82%), for a risk difference of 1.7% (95% CI −12% to +15%, p=0.81). Among patients with chest radiographic findings consistent with TB, empiric TB treatment was associated with increased survival among those with danger signs (Risk difference 15%, 95% CI +0.02% to +29%, p=0.046), but not among those without danger signs (Risk difference 8.7%, 95% CI −3.8% to +21%, p=0.18). Overall, 78 (12.4%) patients were lost to follow-up within 4 weeks and 105 (16.4%) were lost within eight weeks. There were no differences in the frequency of losses to follow-up between those with danger signs (16%) and those without (18%, Risk difference −2.2%, 95% CI −8.1% to +3.5%, p=0.44) or between those receiving empiric treatment (14%) and those not receiving empiric treatment (17%, Risk difference −2.9%, 95% CI −9.8% to +3.9%, p=0.43). Sensitivity analyses based on the extreme assumptions that patients lost to follow-up either all died or all survived did not affect our overall findings.

Figure 2. Survival of severely ill patients with possible TB by empiric treatment status.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves show that cumulative survival among severely ill patients with possible pulmonary TB and had danger signs was higher when they were treated empirically for TB prior to hospital discharge (p<0.0001).

After adjusting for age, gender, CD4 count, baseline antiretroviral use, baseline co-trimoxazole prophylaxis use, prior antibiotic treatment for the current respiratory illness, sputum production, duration of cough, dyspnea, weight loss, and hypoxia, patients with danger signs who received empiric TB treatment had an adjusted absolute risk reduction in eight-week mortality of 17% (95% CI 5.5% to 29%, p=0.004) compared to those who did not receive empiric treatment. The adjusted relative risk reduction was 44% (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.34-0.91, p=0.020) (Table 2). Among those without danger signs, we found no benefit to empiric TB treatment in absolute (risk difference 1.5%, 95% CI −12% to + 15%, p=0.83) or relative (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.53-1.67, p=0.83) terms, although with the low mortality rate in this sub-population, there was insufficient power in the numbers enrolled to exclude the possibility of a clinically important difference in mortality. We observed similar effect sizes for the survival benefit of early empiric TB treatment among patients with danger signs at earlier follow-up time points, and the protection was even greater at those time points (data not shown).

Table 2.

Adjusted risk ratios and risk differences for the effect of empiric TB treatment on two-month mortality among those with and without danger signs

| Characteristic | Adjusted Mortality – Untreated | Adjusted Mortality – Treated | Adjusted Risk Difference | p-Value | Adjusted Risk Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danger signs present | 37% | 21% | 17% | 0.004 | 0.56 | 0.020 |

| 95% CI | 31%–43% | 11%–30% | 5.5% - 29% | 0.34 - 0.91 | ||

| Danger signs absent | 26% | 24% | 1.5% | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.83 |

| 95% CI | 19%–32% | 11%–36% | −12% to +15% | 0.53–1.67 |

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval, TB, tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

Empiric treatment of disease in a population is theoretically desirable when the likelihood of disease is sufficiently high that the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks, taking into account both the frequency of adverse effects and the costs of treatment.10 Historically, empiric treatment of AFB smear-negative patients was discouraged based on the assumption that the risks of withholding TB treatment were low. AFB smear-negative TB patients were not thought to transmit TB and were expected to return for treatment when they eventually became smear-positive without experiencing excess morbidity or mortality. On the contrary, the economic costs and risks of adverse effects from over-treating were thought to be high.11 With growing evidence in recent years that substantial harm is associated with withholding empiric treatment from individuals, especially HIV-infected patients, and that transmission occurs from AFB smear-negative patients12, even in health-care facilities, this perspective is changing. Policies, including the 2007 WHO smear-negative TB evaluation algorithm, have shifted in favor of earlier treatment of persons in whom either the clinical likelihood or the risk of adverse outcomes of under treatment is high.13,14 Consistent with the 2007 WHO recommendations, we found that empiric TB treatment of severely ill HIV-infected patients with one or more danger signs was associated with a 17% absolute risk reduction and a 44% relative risk reduction in mortality at eight weeks. This effect was unchanged after adjustment for relevant covariates, including the propensity of clinicians to treat the most severely ill patients. These findings support WHO guidelines recommending empiric treatment of severely ill patients and negative sputum smear examination results in high TB and HIV prevalence settings.

These results add to literature on the effectiveness of the 2007 WHO empiric treatment approach for reducing mortality among severely ill HIV-infected patients. In the single previous study examining this critical question, Holtz et al found survival to be 15% higher at eight weeks among 187 South African patients with danger signs who received empiric TB treatment according to the WHO algorithm, compared with 338 patients managed according to standard practice.15 Almost all patients in the South African study were non-ambulatory, with non-ambulatory status the most common danger sign identified. In contrast, almost all patients in our study qualified for severe illness based on abnormal vital signs. In spite of these differences, the observed mortality benefit was similar. In both studies advanced HIV-related immunosuppression was common and few patients received ART. Treatment based on abnormal chest radiography did not add benefit to treatment based on danger signs in either study.

Several published studies16,17 evaluated the accuracy of the 2007 guidelines at detecting AFB smear-negative TB without evaluating the effect of guideline-adherent care on mortality. Our study evaluated the use of chest radiography but not the other diagnostic algorithms in the 2007 WHO guidelines (e.g. empiric treatment of PCP). However, previous studies have shown that PCP is uncommon.18 Our evaluation of empiric treatment based on suggestive chest radiography was underpowered, but this failure to find benefit is consistent with previous studies showing that chest radiography does not increase the likelihood of a TB diagnosis in AFB smear-negative, HIV-seropositive patients, especially those with advanced immunosuppression.5,15,16 Even if proven beneficial, routinely obtaining a chest radiograph might contribute diagnostic and treatment delay in low-income settings, where most HIV-infected, presumed TB patients present to private providers and peripheral government clinics where chest radiography services and interpretation are not readily accessible.19

Critically, we found that only about one in five patients with danger signs received empiric treatment as recommended by the guidelines. Similarly, in a recent evaluation of the uptake of the 2007 HIV-TB guidelines in a large government hospital in Mozambique, only seven out of 66 TB patients were treated empirically for TB.20 Although danger signs were common, not one of 514 consecutive patients reviewed even had the danger signs fully documented in the medical record. This observation is consistent with evidence that guideline dissemination alone often fails to change practice21, and suggests that new multidisciplinary approaches to changing clinician behavior based on implementation science are needed to increase evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of TB.

It has been proposed that universal empiric treatment of smear-negative patients with presumed TB in these settings could decrease mortality.22 We found that although the prevalence of TB was similar in patients with and without danger signs, a clear benefit of empiric treatment was only observed among patients with danger signs. However, we did not have sufficient statistical power to exclude a clinically important effect among those with lesser disease severity and lower observed mortality, such as patients with chest radiographs consistent with TB but no danger signs.

This study was performed prior to availability of the Xpert MTB/RIF automated nucleic acid amplification test, and the urinary lipoarabomannan (LAM) ELISA test23, either of which might have helped inform earlier treatment decisions for patients with smear-negative TB. However, Xpert unfortunately has sub-optimal sensitivity in HIV-infected, smear-negative patients in HIV-prevalent areas (43%-62% reported in sub-Saharan Africa).24 Therefore, even a negative Xpert result may not sufficiently reduce the likelihood of TB in a patient with a high-risk presentation in a high TB-prevalence setting. Even as the sensitivity and availability of rapid TB diagnostic tests improves, challenges in implementing these services will likely preserve a role for empiric TB treatment in lessening the impact of diagnostic delays. One approach worth evaluating would be the strategy of starting empiric TB therapy at the time of TB testing in all high-risk patients and using the test results to decide later whether to discontinue TB treatment. For now, since the majority of health facilities still lack access to these new diagnostic tools, empiric treatment should be administered to all patients presenting with danger signs. The early separation of the survival curves during the first two weeks of follow-up emphasizes the terrible cost of any delay in initiating treatment.

Our study had several limitations. First, as an observational study in which treatment decisions were not randomized, it is susceptible to biases such as confounding by indication. This bias would be more concerning if we had found the more severely ill patients less likely to receive treatment, because of a perceived lower probability of survival or any other reason. In contrast, we found that patients with danger signs were actually more rather than less likely to be treated empirically, suggesting an opposite and conservative bias that may have actually diluted the beneficial effect of empiric treatment on survival. Second, some patients were lost to follow-up, but these losses were similar among patients with and without danger signs and among patients with and without empiric treatment, and our findings were robust to several extreme assumptions about outcomes among patients lost to follow-up. Third, we did not include one of the four danger signs, ambulatory status, in our assessment for severe illness. However, in a consecutive random subset of patients, this sign did not add substantially to vital signs in identifying severe illness. Finally, our study was conducted prior to the release of evidence supporting early ART initiation in TB patients with advanced HIV immunosuppression.25-27 However, early ART often may not be provided when a confirmed TB diagnosis is missing, which was by definition lacking in these empirically treated, smear-negative patients. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to confirm the benefit of empiric TB treatment in smear-negative HIV-infected patients with danger signs in the current era of earlier ART and rapid diagnostic testing with GeneXpert and urinary LAM.

In conclusion, empiric TB treatment of HIV-seropositive smear-negative patients with possible TB with danger signs was associated with a halving of the likelihood of eight-week mortality. The 2007 WHO empiric treatment guidelines should be actively and immediately implemented in resource-constrained settings where rapid TB evaluation and diagnostic services are not routinely unavailable.

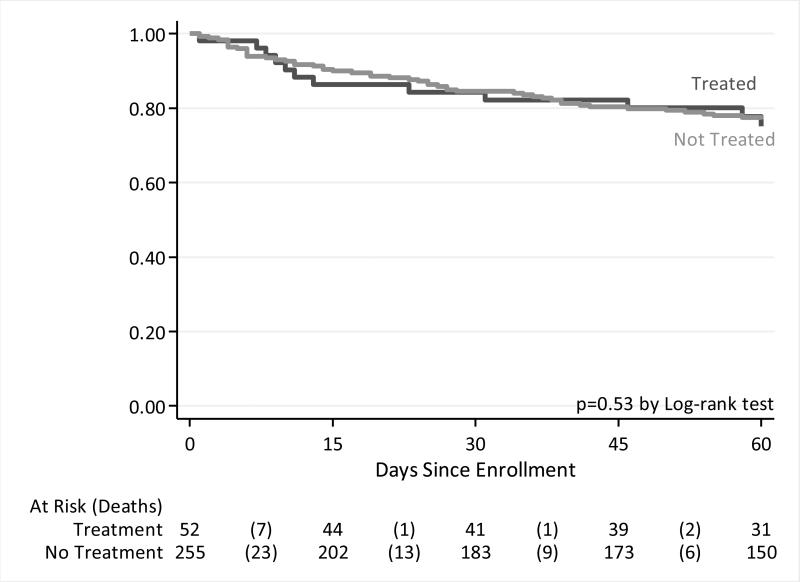

Figure 3. Survival of non-severely ill patients with possible pulmonary TB by empiric treatment status.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves show that cumulative survival among patients with possible pulmonary TB but who had no danger signs yet were started on TB medication empirically prior to hospital discharge was similar whether or not they were started on treatment before discharge (p=0.15).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank all the patients and families who participated in this study, as well as the doctors, nurses, staff, and administrators at Mulago National Referral Hospital who oversaw their care; the technicians, microbiologists, and administrative staff of the National TB Reference Laboratory for performing mycobacteriology assays for the study; Dr. Samuel Yoo for interpreting chest radiographs; and the staff and administration of the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration for making the daily operations of the study possible.

Funding: NIH K24HL087713 (LH), R01HL090335 (LH), K23HL094141 (AC), K23AI080147 (JLD), NIH R21AI101714 (JLD), and NIH/NHLBI K12 HL090147-04 (NDW).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

The data in this manuscript was presented at the ATS 2012 as a poster presentation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hargreaves NJ, Kadzakumanja O, Whitty CJM, Salaniponi FML, Harries AD, Squire SB. Smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in a DOTS programme: poor outcomes in an area of high HIV seroprevalence. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5(9):847–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harries AD. Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection in developing countries. The Lancet. 1990;335(8686):387–390. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90216-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO World Health Organization: Global Tuberculosis Report 2014. 2014 WHO/HTM/TB/2014.2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Improving the diagnosis and treatment of smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis among adults and adolescents: Recommendations for HIV-prevalent and resource-constrained settings. 2007 WHO/HTM/TB/2007.2379. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis JL, Worodria W, Kisembo H, et al. Clinical and radiographic factors do not accurately diagnose smear-negative tuberculosis in HIV-infected inpatients in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worodria W, Davis JL, Cattamanchi A, et al. Bronchoscopy is useful for diagnosing smear-negative tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(2):446–448. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00010210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cattamanchi A, Huang L, Worodria W, et al. Integrated strategies to optimize sputum smear microscopy: A prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(4):547–551. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1207OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uganda Ministry of Health . Manual of the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme. 2nd ed. Ministry of Health; Kampala: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauker SG, Kassirer JP. The threshold approach to clinical decision making. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;302(20):1109–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005153022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toman K. Toman's Tuberculosis: Case detection, treatment, and monitoring questions and answers. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tostmann A, Kik SV, Kalisvaart NA, et al. Tuberculosis transmission by patients with smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in a large cohort in the Netherlands. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;47(9):1135–1142. doi: 10.1086/591974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng J-Y, Su W-J, Chiu Y-C, et al. Initial presentations predict mortality in pulmonary tuberculosis patients - A prospective observational study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e23715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrea S, Gershon WW, Jack V Tu. Delayed tuberculosis treatment in urban and suburban Ontario. Canadian Respiratory Journal. 2008;15(5):244–248. doi: 10.1155/2008/289657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtz TH, Kabera G, Mthiyane T, et al. Use of a WHO-recommended algorithm to reduce mortality in seriously ill patients with HIV infection and smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in South Africa: an observational cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2011;11(7):533–540. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huerga H, Varaine F, Okwaro E, et al. Performance of the 2007 WHO algorithm to diagnose smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in a HIV prevalent setting. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson D, Mbhele L, Badri M, et al. Evaluation of the World Health Organization algorithm for the diagnosis of HIV-associated sputum smear-negative tuberculosis. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011;15(7):919–924. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor SM, Meshnick SR, Worodria W, et al. Low prevalence of Pneumocystis jirovecii lung colonization in Ugandan HIV-infected patients hospitalized with non-Pneumocystis pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;72(2):139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shete PB, Haguma P, Miller CR, et al. Pathways and costs of care for patients symptomatic for tuberculosis in rural Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015 doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0166. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bos JC, Smalbraak L, Macome AC, Gomes E, van Leth F, Prins JM. TB diagnostic process management of patients in a referral hospital in Mozambique in comparison with the 2007 WHO recommendations for the diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary TB and extrapulmonary TB. International health. 2013;5(4):302–308. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/iht025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimshaw J, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay C. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technology Assessment. 2004;8(6):84. doi: 10.3310/hta8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawn SD. Potential utility of empirical tuberculosis treatment for HIV-infected patients with advanced immunodeficiency in high TB-HIV burden settings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawn SD. Point-of-care detection of lipoarabinomannan (LAM) in urine for diagnosis of HIV-associated tuberculosis: a state of the art review. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawn SD, Nicol MP. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay: Development, evaluation and implementation of a new rapid molecular diagnostic for tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance. Future Microbiology. 2011;6(9):1067–1082. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(16):1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(16):1471–1481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Havlir DV, Kendall MA, Ive P, et al. Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV-1 Infection and Tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(16):1482–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]